Search Results for: F word

I was thinking about major screenwriting mistakes the other day and it got me thinking: “What’s the single most common screenwriting criticism given?” I didn’t even have to blink before I had my answer. Or maybe I should say, I didn’t even have to sniffle. ON-THE-NOSE DIALOGUE. Every writer, from beginner to advanced, has heard that criticism numerous times throughout their career. So I thought, “Let’s nip this on-the-nose thing in the bud once and for all.”

But before we do, we must define what on-the-nose dialogue is. I see on-the-nose dialogue as obvious surface-level conversation where the characters say exactly how they feel and/or exactly what they’re thinking. Here’s a blatant example of on-the-nose dialogue:

“How are you today?”

“I’m doing well. How are you?”

“I had a tough day but I’m feeling better now that you’re home. Thank you for asking.”

Ugh. Notice how straight-forward the words are. There’s no emotion. There’s no nuance. There’s nothing unexpected. The characters are basically robots going through the motions.

On-the-nose dialogue can also extend into exposition, where characters will often skip subtlety and deliver only the lines that the audience needs in order to understand what’s going on.

“How are we going to defeat Ragbob the Zombie-God if he’s undead?”

“You said he hated water right?”

“Yes.”

“So we’ll lure him to Smith River and throw him in.”

“But Jake said he becomes immortal at midnight.”

“Then we have to hurry.”

While it’s true that you need to explain what’s happening in your plot at times, notice how these characters don’t appear to be talking to each other, but rather directly to the audience. That’s a good indication that your dialogue is on-the-nose.

So I was searching for an easy way to identify on-the-nose dialogue and I think I found the answer. On-the-nose dialogue is LOGICAL. If I ask you the question, “How many miles per gallon does your car get?” the logical answer to that would be, “I think 28 miles per gallon.” Logically, you’ve answered my question. However, you’ve done so in a very boring, on-the-nose way.

This is what screenwriters have to realize. Real conversation isn’t always logical. Sometimes it is. But often it isn’t. It’s a topsy-turvy mess of fragmented thoughts, unfinished sentences, sarcasm, unspoken secrets, suppressed information, humor, you name it.

Under that reality, you can move away from on-the-nose and give us dialogue that feels more alive. “How many miles per gallon does this car get?” “I don’t know who do I look like, Mario Andretti?” Or, if you were writing a drama: “How many miles per gallon does this car get?” “Not enough.”

As writers, the logical side of our brain is extremely important because we’re constantly having to keep the plot sorted and make sure every scene has a purpose and make sure every character’s motivation is clear and blah blah blah. So it’s only natural that once we segue into dialogue, we keep that logical side of our brain with us.

However, if there’s one thing I want you to take away from this article, it’s that once you segue into dialogue, you want to turn off your logical brain and embrace the illogical. Again, if you listen to real-life conversation, it’s messy as hell. People ramble. Questions are asked and never answered. Or a question is asked but the question reminds the other person of something else they wanted to talk about. People ignore each other because they just received a text on their phone. People aren’t always present in a conversation because their mind is worrying about something else.

You can’t completely capture the randomness of real conversation because real people sometimes have hours to talk, whereas your dialogue scene may take place over three minutes. But you can approximate some of these things to simulate it.

Let’s get back to exposition because in some ways, it’s harder to avoid on-the-nose dialogue in instances where it’s imperative that the audience understand what’s going on. I mean, imagine if, in Back to the Future, they never had any conversations about how they were going to get Marty back to the future and instead just threw us into that end scene. We’d probably be pretty confused.

The most common way to avoid on-the-nose expositional dialogue is through humor. That’s what they did with Back to the Future, and more recently in Avengers: Infinity War, when the Guardians of the Galaxy find Thor and have to split up into two teams to achieve two different goals. I’m not going to say the scene was perfectly-executed, but the use of humor (namely through Starlord’s jealousy of Thor) made all that exposition more palatable.

But sometimes, the genre isn’t conducent to humor. Or, at least, over-the-top humor, such as the examples above. So what do you do then? Well, one thing you can do is go back to basics. What’s the principle tool that makes a scene work? You know this because I made it a focus last week. CONFLICT. If you add an element of conflict, the focus of the scene becomes bringing that conflict into balance as opposed to focusing on the exact words the characters are saying. If you do this, and also sprinkle in a few illogical responses, you can avoid that “on-the-nose” label.

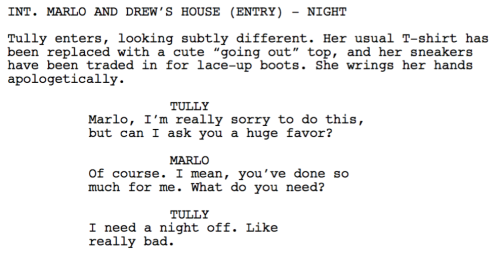

Let’s look at a scene from the movie Tully. This scene occurs late, when Tully (the night nanny who’s been helping our hero take care of her baby) asks Marlo (our hero/overworked mom) to come out with her for a night. While this script isn’t plot-heavy, it’s probably the most plot-centric beat in the movie. This night needs to occur for Margot to finally have fun again and have her breakthrough that will allow her to arc.

Notice how the simple inclusion of conflict (Tully’s asking Marlo to go – Marlo’s resisting) keeps us less focused on the dialogue and more on whether she’s going to do this or not.

You’ll notice that there are some on-the-nose “logical” lines here. “You know, I feel like I’ve been very useful around here. In many regards. And I don’t think this is an unreasonable request. I don’t have a lot of friends my own age, due to the unusual nature of this job, and I just need to get out.” But I never said that everything needed to be illogical. Only that there is a mix of the two. There are plenty of instances of messy fun conversation as well. “Where?” “Out. To the city.” “The city-city?” “Yeah. New York. Big Apple. City that never sleeps.” Later: “Who’s going to take care of Mia?” The logical response to this is, “Your husband.” Instead, Cody went with, “Oh, I don’t know. It’s almost as though there’s another responsible adult at this address. Named Drew.”

It should also be noted that sometimes on-the-nose dialogue isn’t on-the-nose dialogue. That it all depends on the context. For example, let’s look at that opening dialogue example again. “How are you feeling?” “I’m doing well. How are you?” Boring and on-the-nose, right? Except, what if, in the previous scene, we just saw this character brutally murder someone? Cut to them walking in their home and their wife, none-the-wiser, greeting them. “How are you feeling?” “I’m doing well. How are you?” The line feels completely different now, right? It’s actually not on-the-nose at all. A shift in context can quickly change the perception of any dialogue. Important to remember.

But, again, the main thing I want you to take away here is that your mind needs to shift when it moves into the dialogue portions of your script. You need to ditch the robot in your head that’s trying to keep everything sorted and give in to the organic nature of the conversation you’re documenting. Don’t try and force words out of your characters’ mouths. Let them say what they want to say.

Genre: TV Pilot – 1 Hour Drama

Premise: After a real estate developer accepts a half a million dollar loan from a new friend, he learns that the money comes with lots of attached strings.

About: Pitched as a “Hithcockian” thriller, Suspicion is based on a book and adapted for television by Jessica Goldberg, who created the Hulu television series, The Path. It will premiere this fall on NBC. Goldberg studied writing at NYU and started her career as a playwright, winning the Susan Smith Blackburn Prize for her play, Refuge, about a young woman who must take care of her siblings after her parents abandon the family. She would later adapt the play into a script and direct the movie, which starred “Jessica Jones,” Krysten Ritter.

Writer: Jessica Goldberg (based on the novel by Joseph Finder)

Details: 60 pages

One of the reasons network TV is in a bind is because the networks aren’t sure what they’re trying to do anymore. The cool shows that get all the accolades are on premium cable and streaming. So you’d think that the networks would focus on lightweight comfort food, the kind of soapy dishes that don’t require more than a passing investment.

The problem with that is the rise of reality TV, which hasn’t just taken the pole position for comfort food, they’ve injected it with even more comfort. I can turn off my brain, watch Million Dollar Listing, and finish my TV viewing for the day a happy man. This leaves network shows caught somewhere in the middle. And right now the only person who’s figured where that sweet spot is is Shonda Rhimes. And she’s leaving for Netflix.

I bring this up because until the networks figure out how to give people something they can’t get elsewhere, their ratings are going to keep falling. I picked up Suspicion because it sounded slightly different. It wasn’t yet another medical/cop/agent/legal show and it was trying to explore the Hitchcock formula through long-form writing. I liked that pitch. Let’s see how the final product turned out.

We meet 40-something real estate developer Danny Goodman dragging a body from the back of his car. He tells us, through voice over, that it wasn’t always like this. Cut to three months earlier and Danny is asking his beautiful girlfriend, Lucy, to marry him. Oh, and get this. Danny’s 16 year old daughter, Elise, whose mother died of cancer five years ago, actually LIKES her new mother. After much pain, Danny’s life is finally back on track.

As is Elise’s. She’s finally making friends again. Her new best friend, Tatiana, happens to belong to one of the wealthiest families in town. And when Tatiana’s family asks Danny’s family over for dinner, Danny doesn’t hesitate.

Except that before he goes, he learns that the building he recently bought, the one that he bet his entire business on, is decrepit and falling apart. It’s going to cost hundreds of thousands of dollars in repairs, money he doesn’t have.

Once at the dinner, Danny meets Tom Canter, Tatiana’s father. Tom is brazenly charming and overly thankful for the emergence of Elise in Tatiana’s life. Before her, Tatiana was on a path of destruction. In Tom’s eyes, he owes Danny everything. So when he overhears Danny talking to his lawyer later about the building, he offers to help Danny out. Danny feels odd about it, but he’s really in a bind, so the next day he accepts half a million dollars from Tom.

It doesn’t take long for the FBI to show up at Danny’s work. They explain that Tom is involved in money laundering, securities fraud, illegal campaign contributions, you name it. They tell Danny that unless he works with them, he’ll go to prison for the next 30 years. And that’s how Danny finds himself working as an informant for the FBI to take down one of the most dangerous men in Boston.

Let’s get back to that question. Was this different from any of the other network TV shows on the air?

Not really.

But if you want to write for TV, this is a really good pilot to read in order to understand structure and pacing.

Last week I reviewed Lodge 49 and that pilot read like the writer kept falling asleep between scenes, only to wake up a few hours later, down a bag of chips, smoke a joint, write another scene, then go to sleep again. It didn’t seem like he cared about your time at all.

This reads like a writer who understands how quickly stories need to move in 2018. We get the teaser with the car dragging the body. And in the VERY next scene, which we cut to three months prior, the main character asks his girlfriend to marry him.

After a few brief scenes with the family, we establish that Danny is in a lot of trouble with the building. From there, the family goes to Tom’s. We meet Tom. But we don’t fart around. A major story beat is introduced (Tom overhears Danny’s phone call then offers him money).

The very next day, Tom goes to work, and the FBI is there. Again: THIS IS HOW QUICKLY YOU WANT THINGS TO MOVE. After that, the agents force Danny to download information on Tom’s phone. So that becomes a set-piece.

Always moving always moving always moving. If your story isn’t moving, it’s dying.

If you need help moving your story faster, use Act Breaks. There are FIVE ACTS in a pilot. And you know that at the end of each act, there needs to be a cliffhanger. So all you need to do is write towards that cliffhanger. Every scene should be moving that portion of the story towards that cliff.

Here, the end of Act 1 takes place on page 20. The end of Act 2 takes place on page 32. The end of Act 3 takes place on 41. The end of Act 4 on page 49. And the end of Act 5 takes place at the end of the script, page 60.

I don’t know why the acts are set up this way, with such a long first act. But I’m guessing that it gives you extra time to introduce all the main characters as well as their situations. Either way, it’s easier to keep the pace up if you’re writing inside of a small portion of pages. If you’re not using acts and just trying to get to page 60, you’ll likely write something with a similar urgency to Lodge 49.

So yeah, there’s no new ground being broken here. But wow is this a tight teleplay. There isn’t an inch of page space that’s wasted. Every moment is moving the story forward. If you’re a writer who’s been told that your scripts are slow or boring, you can learn a lot from this pilot.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t use the word that’s correct. Use the word that’s real. — Check out this line of dialogue:

“I’ve spent my entire adolescence sad and scared– thinking I’d never be a normal, happy kid…”

The line comes from Ellie, the daughter, complaining to her father after he retrieved her from a party. Why am I highlighting it? Because of the word “adolescence.” A 16 year-old wouldn’t use that word. And yet, I understand why it was chosen. As writers, we focus so much on getting the word CORRECT that we often overlook what the character would ACTUALLY SAY. In the writer’s mind, Ellie’s sadness and fear began with the death of her mother, which occurred at the beginning of her “adolescence.” Hence, it technically makes sense to use that word. But dialogue isn’t technical. It’s off the cuff. It’s messy. The wrong words are often used. You have to honor that when your characters are speaking. It’s more likely Ellie would say something like, “I’ve spent my entire life…” or “I’ve spent so long…” or “I’ve spent the last five years terrified…” It’s easy to forget this. Use the word that’s real, not the one that’s technically correct.

One of the worst things that can happen in screenwriting is to write a script and then, 45 pages in, 60 pages in, 75 pages in… you run out of ideas. You don’t know where the story should go. You stare at the screen, you rack your brain, but no matter how hard you try, you don’t see any way to complete the story. Maybe, you say to yourself, the idea was never good enough to begin with. Maybe there was nothing here from the start. And while that may be true, running out of ideas during a screenplay is a common problem. Sometimes the brain just stops working. The good news is, there are ways to combat this.

First of all, the biggest reason we run out of steam during a screenplay is because we didn’t outline. Outlining helps us see if the story has legs. If you’re not a fan of the outline, that’s fine. But I would still implore you to write down four major checkpoints in your script before you start writing it. What happens at the end of the first act (the launching point). What happens at the midpoint (a twist or major event that shakes your story up). What happens at the end of the second act (the lowest point). And your ending.

If you have these figured out beforehand, you’ll always have something visible to write towards. A big reason we run out of ideas is because the void in front of us is too big, too uncertain. We see 60-70 pages ahead of us and there aren’t enough ideas in the world to fill that up. But if our next pre-determined checkpoint is never more than 30 pages away, that feels more manageable. We can come up with enough ideas to get to that point.

But let’s say you’ve outlined your script only to find that, midway through the writing process, your outline was wrong. Or maybe you had a better idea that spun the story in a different direction, and now your outline is worthless. This happens all the time. Storytelling is malleable. You get new ideas. You follow new paths. You find yourself in unexpected territory constantly. So even if you had the best intentions and did things “right,” you can still find yourself halfway in with nowhere to go.

My experience has been that everything comes back to the active character. An active character is someone who is always trying to achieve something at every moment of the movie. The characters in Jumanji are always trying to get out of the game. In Blockers, the kids are all trying to get laid. The adults are all trying to stop the kids. The Equalizer always has a bad guy to take down. The Game Night couples are all trying to solve the murder-mystery first. The mom and the son are trying to escape their captivity in Room. As long as your character is active, they’ll always have something they’re trying to do, which means you’ll always have somewhere to take the story. Conversely, if you build your movie around a passive, reactive, or occasionally active character, it becomes infinitely harder to come up with ways to keep the story moving. Because instead of your hero racing towards something, you’re trying to come with outside factors that give your hero something to do. And that’s a lot harder.

Tully is an example of a script that’s easy to run out of ideas during. The main character is mostly sitting around the house the whole movie. Or a script like Call Me By Your Name. You’ve got two characters hanging around in a town passing time. Now both of these movies were reviewed well, so I’m not saying this is a death sentence. I’m only saying that when you build stories around inactive characters, you will definitely run into more walls during the writing process, especially if you didn’t outline beforehand.

Now that you know this, use it to your advantage. Have your main character be more active. An active character is a goal-driven character. They typically have an overall goal they’re trying to achieve (the goal of the movie) and then a series of goals they need to achieve to accomplish the major goal. So whenever you’re stuck, you simply give your character another “mini-goal” that they have to achieve. This mini-goal could set up your next scene, your next couple of scenes, or an entire 15 minute sequence. For example, in Deadpool 2, the goal is to get the kid. So technically, you could have Deadpool run off and get the kid and be done with it. Instead, they make getting the kid impossible. So Deadpool needs a team. This leads to a new goal – put a team together. This adds 10 pages to your story. As long as you have an overarching goal for your hero to achieve, an active character will always have smaller goals he needs to achieve in the meantime.

Another method for extending the story is to keep throwing disruptions at your hero, leading to their failure, which forces them to try again. There was a famous article over at Wordplayer about how Raiders of the Lost Ark was one giant series of Indiana Jones failures. But it works because Indy gets back up and tries again. He’s active. He keeps going after the goal. In my favorite film from last year, Good Time, the goal is to get the brother out of jail. Out hero’s first goal is to try and get money for bail. But before he can get it, his brother is beat up and transferred to a hospital. New goal. Break him out of the hospital. Our hero successfully breaks him out, only to find out that he took the wrong patient (his brother was wearing a face cast). So now he’s got to save his brother again. If there aren’t a series of goals already in place to get your hero to the climax, keep throwing obstacles at them that force them to try again.

But let’s say you’ve tried all that and you’re still coming up with nothing. What do you do? Do you give up? Do you put the script away for awhile? When it comes to nuts-and-bolts sitting down to write, this is where the rubber meets the road. It often comes down to how dedicated you are to this script and to writing in general. Because if you’re only half-in, you’re not going to fight when the chips are down. And the chips are down a lot in writing. You’re always battling against a lack of ideas, a lack of creativity. And it takes a steel backbone to muscle through these moments. This is why I always tell writers, make sure you’re PASSIONATE about any script you choose to write. Because, sure, it’s easy to be excited at the beginning. But do you love this idea enough to fight for it on Draft 5 one year from now?

Here are a few things you can do. You can use the vomit approach. That means erase all judgement and, no matter what, keep writing. Coming up with something to write isn’t difficult. Coming up with something GOOD to write is. But if you only write when you have good ideas, you’re going to be spending a lot of time staring at your screen and getting frustrated. So muscling through those shitty “no ideas” moments is one approach. And the good news is that you’re way more likely to come across a great idea if you’re writing than if you’re sitting and trying to come up with it out of thin air.

Another thing you can do is write two projects at the same time. Whenever you’re struggling with one project, you simply switch over to the other one. It’s best if these projects are as different as possible. A horror and a comedy. A feature and a pilot. We spend so much time inside our scripts that we begin to hate everything about them. To be able to jump to a completely different universe with a different set of rules is just the thing the mind needs to stay engaged and creative. I think I read a Jordan Peele interview where he touts this writing approach.

Another method I found useful is to take your phone out, set the timer for 30 minutes, and just write for the full 30 minutes. You don’t have to write ANYTHING after those 30 minutes. Just 30 minutes each day and you’re done. What you’ll find is that a freedom emerges where you don’t feel the pressure to write the perfect screenplay, but rather you’re just accomplishing a task. My experience has been that if you do this for a week or two, you’ll be back on track, with a full set of ideas to get your script finished.

To summarize, the main reason we run out of ideas during a script is because we didn’t plan ahead of time. Outlining is a screenwriter’s best friend. The next biggest problem is an inactive main character. It’s hard to push the story forward when your hero doesn’t have an objective. So write inactive heroes at your own risk. And finally, if you’ve done everything right and you’re still stuck, blunt force may be the only option. This is not a fun way to write, but it’s important to remember that writing isn’t always fun. It’s often work. So get to work, push through those tough moments, and hopefully there’s some fun on the other side.

Genre: Action/Adventure

Premise: When a teenage boy comes across a map for a treasure buried on a remote island, he joins a motley crew to retrieve the treasure, only to realize that the crew has other plans in mind.

About: Today’s script landed on the 2015 Black List. It’s based on the 1883 novel, Treasure Island, which is one of the most adapted stories in history. The script was written by James Coyne, who was supposed to write Sherlock Holmes 3 before they backed off and decided to do one of those writers’ rooms. Coyne more recently sold a sci-fi pitch called “Cascade” to Paramount, although not much is known about that project. Treasure Island was originally written by Robert Louis Stevenson who was a bona fide writing celebrity when he was alive (I wish they’d bring those days back!). In addition to Treasure Island, he wrote The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde.

Writer: James Coyne (based on the book by Robert Louis Stevenson)

Details: 120 pages (Draft 1.1)

So yesterday, Sony officially announced a Fantasy Island movie (“Da plane da plane!”). That got me in Island Fever mode, so I decided to check out Treasure Island, an adaptation of the famous book I’ve never read. Islands are one of the best places to set a story because there’s nowhere for your characters to go. They have to confront the antagonist if they’re going to make it off the rock alive. Throw in some treasure hunting and you’ve got yourself a story.

This also falls in line with my advice that old IP is always on the table with studios. Tell them you have a romantic comedy set in Nashville and their eyes roll. Tell them you have a new take on a Charles Dickens or Shakespeare tale and they lean forward, rapt with attention. Case in point, just yesterday a new take on Romeo and Juliet sold, this one set in Brooklyn with sword-wielding Capulets and Montagues.

Of course, you don’t have to go with a new take. You can do what today’s writer did and stay true to the source material. Either way, old IP gives you a leg up in pitch meetings. That’s for sure. Let’s see what Coyne’s done with this classic tale.

15 year old Jim Hawkins is devastated after his father passes away. But he doesn’t have time to mourn. That’s because a band of pirates led by the evil “Black Dog” have sailed onto shore and are headed to Jim’s Inn. What neither us nor Jim know is that a Captain who lives at the Inn has a map to Flint’s Island, where an enormous treasure is hidden.

Black Dog’s crew bursts into the Inn and starts killing everyone, prompting Jim and his mother to sneak away, but not before they stumble upon the captain’s map. Somehow, the two are able to escape, and head to a local port where they commission a ship to obtain the treasure. But then Black Dog, who’s secretly followed them here, pulls Jim into an alley to kill him. Just before doing so, a sword appears through Black Dog’s chest. This sword belongs to the charming Long John Silver, who so happens to be a part of Jim’s crew.

On the way to the island, Jim overhears his new supposed friend, Silver, say that he and the crew are going to take the treasure for themselves then kill everyone on board. After Jim tells the Captain, the other passengers must pretend like they don’t know the plan. Once they get to the island, they’ll leave the crew and get the hell out of dodge. The clever Long John Silver senses something is amiss, however, and refuses to go exploring without Jim.

From there, Jim must figure out a way to escape Silver and his vagrants, get back to the boat, and get off the island. But as new wrinkles emerge, and an overall greed for the treasure surfaces, getting off the island for anybody becomes more and more unlikely.

Man, I can’t remember the last script I read that has this much action. As you guys know, this is how I say to do it when you’re writing period stuff. Let us know immediately that you’re here to entertain.

I would say that the opening act here is one of the best opening acts I’ve read this year. It’s relentless. The way we establish our hero, Jim, then we cut to the pirates, coming ashore and preparing to attack. Then we cut to the local militia, who’s gotten word of the landing. The way Coyne jumps back and forth between these three parties during this attack is captivating.

And it isn’t just the intensity. It’s the characters. These characters are so well drawn. The ragged shadowy Pew, who has no eyes. Black Dog, who’s all business and determination. The Iroquois warrior, River, who is a battling beast for the militia. Ruthie, the giant of a man who can’t be taken down. Squire, an aging soldier who refuses to let age define him. Obviously, these are all Stevenson’s creations. But boy do characters this rich make a difference. It’s rare that I encounter one character this memorable in a script. Much less the dozen in Treasure Island.

But I want to draw your attention to an important detail here because beginner screenwriters miss this. This action-packed first act doesn’t work unless we set up the character of Jim beforehand. Coyne (or Stevenson – not sure if this plays the same way in the book) starts the story with Jim’s father dying. It’s a brutal scene. His father is sick in bed, down to his last few minutes. The doctor tells Jim that if there’s anything he wants to say to his father, he needs to do it now. Then we get their final conversation.

To understand why this is important, you have to imagine the first act without this scene. Say we meet Jim waking up and the next thing you know, pirates are raiding the Inn. We’re not as invested in Jim’s escape because we don’t know him. By spending that one intense emotional beat with Jim, we want this kid to survive more than anything. Which means that all this action has a purpose – to create doubt about whether this character we now love escapes or not.

And for those of you who say, “Ah, but Carson, we know he’s going to survive. He’s the hero!” Let me tell you something about this script. You never know what’s coming next. It was full of surprises. (Spoilers) They escape the pirates, they go to the port, Black Dog, who we thought was gone, reappears, tries to kill Jim, who’s saved by Long John Silver, who we fall in love with, only to later realize is a bad guy, but who later still turns out to be a good guy! The script constantly kept me off-balance. And we’re talking about a 150 year old story.

I was on my way to giving Treasure Island an “impressive” until we got to the island. That’s when things got sloppy. The script kept up its insane pace, but without the clarity that the first act had. Jim was with the pirates on the island, who he was trying to escape, while the boat itself was constantly moving around the island. For awhile there, I wasn’t clear what Jim’s plan was, or the guys on the boat for that matter (why did they keep sailing to different points on the island??).

Luckily, everything came together at the end, once they found the treasure. I loved how Silver’s team abandoned him, forcing him to team up with Jim. As they fought their way back to the boat, you were constantly wondering, “Is Silver really an ally? Is he going to betray Jim?” The only way to find out was to keep reading. And that’s the name of this game, right? Creating scenarios that give the reader no choice other than to keep reading. They have to know what happens next.

I don’t know where they’re at with this project but it feels to me like a nice successor to the dying Pirates franchise. My only reservation is building the story around a 15 year old. The overall tone has an adult feel to it (a typical line of dialogue: “Tighten up that gallant, it’s looser than a fat tart’s cunny!”). Harry Potter this is not. Maybe if they upped Jim’s age to 20, you’d have yourself a film.

Really enjoyed this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Between yesterday and today, we see the power of entering stories during a major transition in someone’s life. In Castle Rock and Sharp Objects, it’s coming home for the first time in decades. In Treasure Island, it’s the death of the hero’s father. Life transitions force characters to reevaluate everything, or at least things they’ve been suppressing. This opens the character up in ways you don’t have access to if you meet them during their run-of-the-mill existence. So consider starting your story during a major transition in your hero’s life!

Genre: 1 Hour TV Drama

Premise: An anthology series that is said to take the entirety of the Stephen King universe and tell new original stories within that universe, with the occasional assist from known King characters.

About: Castle Rock is the long awaited “Stephen King Universe” show that JJ Abrams brought to Hulu. The show is being spearheaded by Sam Shaw and Dustin Thomason, who created the ambitious but ultimately canceled, “Manhattan.” JJ Abrams was said to be a big fan of the show and had wanted to work with Shaw and Thomason. So when they pitched him this idea, he was immediately on board. The show debuted last week.

Writers: Sam Shaw and Dustin Thomason (based on Stephen King’s books)

Details: 55 minutes

I’ve been looking forward to this show since the day they announced it. With “It,” Hollywood finally figured out how to do Stephen King horror right. While King can be goofy and weird, his adapted material works best when it errs on the dramatic side. That’s where JJ’s taken his cue with Castle Rock – a serious jaunt into the Stephen King universe. In fact, I’d call this trip Fargo-Adjacent. Not a bad tone to set your TV show to.

However, I’ve been down this road before with JJ and Hulu. 11/22/63. I thought that show was going to be amazing. But by the fourth episode, I felt like I was watching concrete harden. Which is ironic since that show was about as solid as soft serve ice cream. In retrospect, I realized the concept was flawed. You’re sent back in time to stop the Kennedy Assassination but you arrive two years prior to the assassination. So you have to sit around and wait for two years? Talk about anti-urgency.

But JJ being the genius he is, he knew how to suck me back in. Begin Castle Rock at Shawshank? Shawshank as in the prison in the best movie ever made? Well, duh. Can I be admitted as a prisoner? And in double-dose JJ fashion, we meet the warden of Shawshank as he drives his car off a cliff while hanging himself at the same time. I know, right? wtf???

We quickly learn why he’s done this. It turns out the warden was keeping a kid in a cage in the basement of Shawshank. When that kid, now a young man, is rescued, he says two words, “Henry Devers.” Henry Devers? Who the hell is Henry Devers?

Henry Devers, it turns out, is a lawyer who grew up in Castle Rock. He comes back to town to learn why this tortured kid is asking for him. And that’s when we learn Henry has his own complicated past. When he was a kid, he disappeared for two weeks during the dead of winter, with temperatures in the negatives. Nobody could’ve survived that. Yet Henry shows up two weeks later in the forest, completely fine, with no memory of what happened.

As we make our way to the end of the pilot, the focus is placed on the weird kid who was rescued from a cage. The word ‘creepy’ doesn’t do him justice. And right now, no one knows what to do with him. I mean, he doesn’t even have a name. Then, without warning, all the power in the prison goes out, and when it comes back on, he’s no longer in his holding room. Cut to black.

This one was a doozy. It was awesome in parts. Slow in others. All in all, it made me a believer, but not without some reservations.

For starters, there’s the “coming back home” template for a show. Yes, it’s used a lot. But it’s used a lot because it works. You may note that it’s the template for the new HBO show, Sharp Objects, as well.

The reason this format works is because you’re immediately dropping your hero into a world of unfinished business. You have to remember that TV shows are about character. Character development, character struggle, character relationships. Way more so than movies. So imagine, then, that you can place a character in a situation where you have 5-10 unresolved situations with other characters right away. Your show is off and running within minutes. That’s what the “come back home” template gives you.

Castle Rock combines this with what JJ does best – MYSTERIES. Every pilot needs to set up a series of mysteries. Somewhere between 1-4 in the opening episode. If it’s one, it needs to be really powerful. If it’s four, you can spread the wealth a bit. Also, the type of mystery will vary depending on the genre. If you’re writing a legal show, the mysteries aren’t going to be as intense as if you’re writing a sci-fi show or a show like Castle Rock.

Now you may say, but the internet told me mystery boxes were bad, Carson! There’s no doubt that mystery boxes can get you in trouble. If all you’re doing is leaving a trail of mystery boxes with no idea of what’s inside, expect to pay the price. But as long as you have a plan for each mystery box, you’re good. And even for those of you who are mystery box adverse, you can’t avoid it in television. You need to give the audience a reason to keep watching the show and mystery boxes are one of the most effective ways of doing so.

Here, we have two big ones: Who is this kid that’s been kept in a cage for the last 15 years? And what happened to Henry Devers all those years ago when he disappeared for two weeks?

Those two mysteries hooked me, especially the kid in the cage.

But I do have a problem with the show, which is that it’s not taking advantage of the “come back home” format enough. Nobody seems to know Henry Devers outside of his mom. They know his story – how he disappeared. But he doesn’t seem to have any relationships with people. It’s almost as if he left town the day after he was found in the woods.

As a result, Henry Devers feels detached from the world surrounding him. We’re not learning enough about this person. Contrast this with Sharp Objects, which has its main character, Camille, coming back home to investigate the disappearance of a young girl (that’s the mystery driving that show). Camille is constantly running into people she knows, old friends, friends of her mom, acquaintances. This allows us to establish unresolved relationships that can now become the engines for each episode.

Castle Rock, I think, wants to wrap its main character in a mystery box. And I’m not sure that’s a good idea. A mystery box arriving in a mystery box? We need something to ground the story, something solid to latch onto. If everything is floating around us, just out of reach, we get frustrated and want to go home.

With that said, I’m still intrigued. The writers have definitely captured the essence of the King universe. And I’m curious what they’re going to do with some x-factors here. Such as the fact that Bill Skarsgård, our “boy in the cage” also happens to play Pennywise the Clown in “It.” Are they going to connect the show with the “It” movies? That would be cool. Or that Sissy Spacek, who played Carrie in Carrie, is Henry Devers’ mother. Might there be a surprise reveal there? This is JJ, remember. And don’t get me started on how cool it is to see Shawshank again. The more time we get to hang out there, the better.

So they’ve got my attention. I’m watching the second episode now and enjoying it. At the very least, this feels like it will surpass 11/22/63.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “Come Back Home” template is one of the strongest templates there is for a television show. Just make sure that you have 4-5 unresolved relationships set up and ready to go as soon as your hero touches down.