Search Results for: F word

One of the things that separates professional writers from amateurs is character work. Their characters are deeper, more compelling, and overall more memorable. Unfortunately, it’s difficult for the amateur writer to understand WHY their characters lack these qualities. All they hear is, “The characters lacked depth,” or “The characters weren’t three-dimensional.” What the hell does that mean? How do I fix it? Even if you asked the person who gave you the note, they probably wouldn’t know. Creating rich compelling characters is the hardest thing to do in writing.

Luckily, you’re talking to the guy who’s read every script on the planet. And if there’s one thing I’ve discovered, it’s that when a character goes bad, it’s because the writer doesn’t understand the basics of character creation. They may have added a flaw, some inner conflict, a vice, and yet they keep getting the note that the characters don’t work. The writer points to his script: “But look! The proof is right there! I’ve added all the things I’m supposed to add. You’re wrong!” Sorry, just because you have bread, beef, and thousand island in your fridge doesn’t mean you know how to make a Big Mac.

I’m not going to give you ALL the ingredients to creating a great character. There’s too much. An extensive backstory. Approaching the character truthfully. Creating the kind of person who says interesting things and talks in an interesting way (which leads to good dialogue). And yes, strong flaws, some inner conflict, and a well-explored vice help as well. All of that takes years to master. But what I can give you is the base from which to start. If you can get that base right, all of the other stuff will come. How do you find this base? You ask a simple question: What’s their thing?

A character’s “thing” is the component that defines them within the construct of the story. Strip away the bullshit. Get to the core. What is the thing that defines them? Bobby Riggs’ “thing” in Battle of the Sexes is that he can’t handle being out of the spotlight. He’ll do anything to stay in the public eye. Liam Neeson’s “thing” in Taken is that he wants to make up for all the lost time with his daughter and is willing to do anything to get back in her life. Tommy Wiseau’s “thing” in The Disaster Artist is that he just wants a friend.

If you understand that beyond the bullshit, all that confusing flaw/conflict/vice shit, that a character is just looking for a friend, it becomes so much easier to write the screenplay because the majority of the scenes will involve challenging this premise. An example from The Disaster Artist would be when Tommy comes home after a long day and finds Greg in their apartment with his girlfriend, watching a movie. You can see the jealousy dripping off Tommy’s brow, and while he pretends to be okay with everything, there’s a sting to his words, a fear of betrayal. This man’s thing is that he just wants a friend. Here he is potentially about to lose one to this girl. That’s what makes a good movie scene.

If you don’t know your character’s thing, you can’t write a scene like this. I’ll give you an example, and it’s from my least favorite movie of last year, Beatriz at Dinner. The movie was about a poor masseuse/healer who gets stuck at her rich client’s home during an important dinner. The writer tried to get too cute and give the character too much going on. As a result, we had no idea who she was. And the choices that the story made were, predictably, directionless as well. At first Beatriz was a voice for the poor and overlooked. But then they introduced this thing about her loving animals and being upset that animals were being abused (what the fuck???). And then she becomes suicidal, which contradicted everything that had been set up about her. The character was a complete mess and it’s because they tried to do too much. They should’ve asked, “What’s her thing?” and stuck with that thing!

This is a huge problem with screenwriting in general is that writers think they have to get too complex. The solution is almost ALWAYS to simplify, not complexify.

To help you further understand this tool, here are 15 characters and their “thing.” A couple of points I want you to notice. First, take note of how SIMPLE they are. And second, remember how the majority of the scenes in the movie put that thing to the test. So with Mikey in Swingers, every scene either mentions Mikey’s ex or, if it doesn’t, deals with it indirectly. Mikey losing at blackjack is only made worse by the fact that he has no one to emotionally support him anymore. Okay, let’s take a look…

Peter Parker – Wants to save the world despite the fact that he’s not ready.

Mikey (Swingers) – He can’t get over his ex-girlfriend.

Jordan Belforte (The Wolf of Wall Street) – Craves excess. Always wants more.

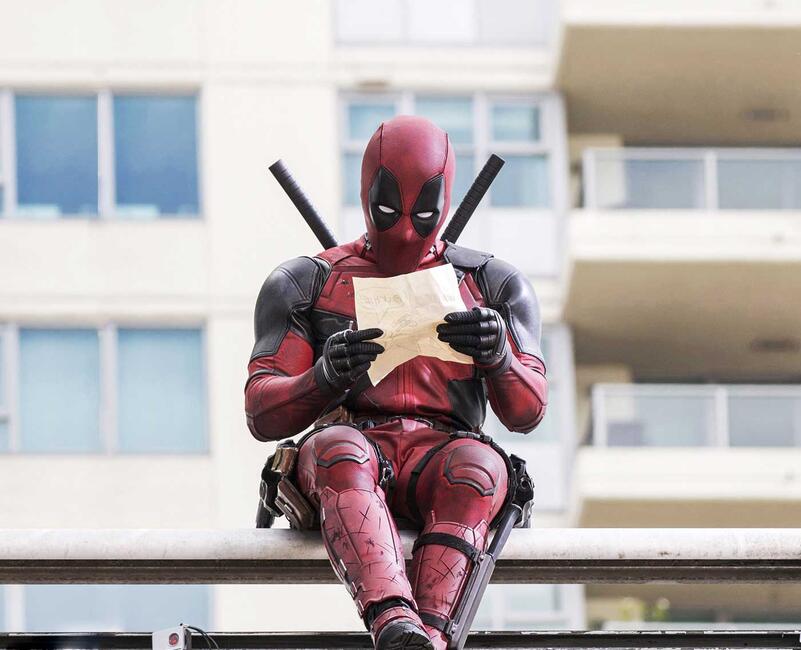

Deadpool – Wants revenge.

Rick Blaine (Casablanca) – Doesn’t stick his neck out for nobody.

Luke Skywalker (Star Wars) – He dreams of making a difference and going off to do bigger better things.

Ferris Bueller – Just wants to have fun now, embrace the moment.

Furiosa (Fury Road) – Get these women to safety.

Harry (When Harry Met Sally) – Doesn’t believe men and women can be friends.

Officer Hopps (Zootopia) – Prove that anybody can do anything if they put their mind to it.

Mila Kunis (Bad Moms) – Sick of being perfect.

Robert Pattinson (Good time) – Will do anything for his brother.

Anne Hathaway (Colossal) – Can’t get her shit together.

Matt Damon (The Martian) – Methodically solve each and every problem one at a time.

Tommy (Dunkirk) – Survive by any means possible.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. I highly recommend not writing a script unless it gets a 7 or above. All logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: Cop Drama

Premise: Two rookie Chicago cops find themselves embroiled in a multi-gang heroin war.

About: This script finished in the middle of the pack on the 2009 Black List. The writer, Justin Britt-Gibson, has written on some high profile shows, including “The Strain,” “Banshee,” and “Into the Badlands.”

Writer: Justin Britt-Gibson

Details: 110 pages

If you take anything from today’s review, let it be ELEVATION.

More than EVER you need to elevate your ideas. You’re no longer competing with E.T. and The Mask. You’re competing with superhero movies that all have 200-300 million dollar budgets. So if you’re not elevating your ideas to bring something new to the table, you’re going to get swallowed up.

Don’t write a drama about the difficulties of a two-race relationship. Write Get Out.

Stay too close to the template of a genre and I’m telling you, you’re toast. You have to add something more.

William Finley is a fresh-faced African-American cop on the Chicago police force, and on his first day of duty, he’s teamed up with fellow rookie James McCoy, an alcoholic dick who’s been sent here by his rich father as punishment for being such a fuck up in life. The two are tasked with escorting a medium-level thug named “Q” across town.

Meanwhile, a wild card crime boss named Hanson steals millions of dollars worth of heroin from former kingpin Frank Russo. I say “former” because Hanson kills him. Hanson then pulls a Joker, recruiting all the big gangs in Chicago, and tells them that he’s now the top drug dealer and all of them have to buy from him.

Finley and McCoy are so incompetent, Q escapes, which means they have to go looking for him. They eventually find him dead, shot execution style, and tab Raymond Priest, Nu Country Gang Leader and just released from prison, as the likely killer. So the guys go looking for Priest, who turns out to be connected to Hanson.

But that’s when the cops discover the capper. Hanson is connected to the cops. Which means it’s the CHICAGO PD who really took that heroin and are selling it. Poor Chicago. Can’t seem to shed that corruption label ever since Capone. Anyway, once Finley and McCoy know the truth, they’re targeted by their own, and must not only survive, but figure out a way to take out the snake inside the organization they work for.

The reason I read Streets on Fire was because it was set in Chicago and I thought it’d be fun to read something about where I’m from. Fail.

Here’s the thing, guys. If you’re going to write in a 100 year old genre – Cops and Robbers – you better think long and hard about how you’re going to bring something new to that world. And if you can’t? Don’t write it. Because nobody wants to read a generic cops chasing bad guys movie.

One of the only ways you can still write in this genre is to world-build. Treat your cop movie like Star Wars. Or Harry Potter. I don’t mean make it a fantasy. I mean wherever it’s set, build that world up so that we FEEEEEEL the mythology of this place you’re telling us about. The Godfather is a great example. There’s no other movie in history that gave me a better feel for the Italian mafia than The Godfather. Sicario is a solid example, too. That one didn’t get AS MUCH into the mythology of border patrol as Godfather did the mafia. But it did enough so that I felt like I was in a unique world learning new things.

I grew up in Chicago. And there wasn’t anything in here that reminded me of the city. The fast food. The crazy weather. The racism between white cops and the black populace. How every single street is filled with potholes. How much the town loves its sports. In other words, this could’ve been set anywhere. And once that happens, you’re writing a generic cop drama. And this isn’t 1983 anymore. Those don’t sell. You need to give us more.

And, to be honest, mythology and world-building should be your last option. You should be looking to elevate the genre in some way. Or go with more of a high-concept hook, like Safe House or The Equalizer. You can also get way with cop period pieces, which gives the genre an, ironically, fresh feel.

After I finished this, I thought to myself, why would anyone write this? Even in 2009, this genre was dead. And then the genius of this spec hit me. This is the PERFECT spec to write if you want to work in TV. The majority of TV is built around the procedural format. So if you can write a good cop flick, you’ll be in high-demand on the TV market. And that’s exactly what happened with Britt-Gibson. He’s worked steadily on some high-profile TV shows.

And maybe that’s the big lesson for today. Selling a script is hard in these times. So play the long game. Make your script a resume for whatever you want to write in. Whether it’s television or a certain movie genre, whatever. If you can execute an idea well, you can get work writing similar ideas.

But yeah, this kind of thing is so not for me. It actually pains me when I have to read stuff that’s this generic. It’s writing, guys! Your job is to ELEVATE! Give us something bigger than the norm.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whatever qualities you give your characters, you have to then figure out WHY they have these qualities. You can’t just make a character an asshole “because.” McCoy is the best thing about this script. He’s the character who sticks out the most. Also, he’s entitled and a dick. So you have to explain, at some point in the movie, WHY he’s entitled and a dick. Britt-Gibson eventually reveals that McCoy’s dad always bailed him out of trouble, he was a star athlete, he’s lived a charmed life, never had any responsibility. Of course he’s a dick. When you do that extra work, your character feels MORE TRUTHFUL because his behaviors are based on a real past as opposed to a couple of adjectives.

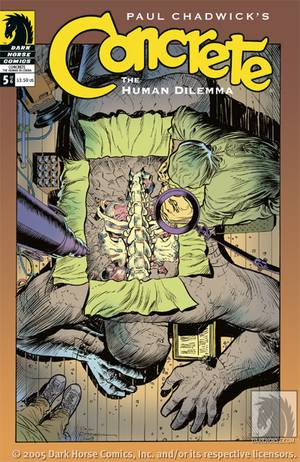

Genre: Superhero

Premise: When a man goes rock climbing with his friend, he’s abducted by aliens and inexplicably turned into a giant rock creature.

About: Concrete was a cult comic book in the late 1980s, birthed out of the Dark Horse comic book label. The creator, Paul Chadwick, has worked in comics forever and, in 2005, became a key creative force behind The Matrix Online, a multiplayer game set up by the Wachowskis to continue the Matrix storyline. I knew nothing about this comic but became interested when I looked at the comic’s art, which has a haunting quality to it.

Writer: Paul Chadwick (writer of the screenplay and creator of the comic)

Details: 107 pages (undated – but somewhere in the 1990s)

I have an intriguing question for you. How would you rank individual superhero properties at this moment? Batman used to have a stranglehold on the top position. But I don’t think he does anymore after these DC disasterfest flicks. You could argue that Batman might not even be in the Top 5 anymore. Deadpool. Wonder Woman. Iron Man. Spider-Man. Captain America. Who do you think owns the sandbox?

The question has me wondering what makes a comic book movie stand out these days. There are SO MANY that simply having a dude with a gruff voice and a bat-mask isn’t enough anymore. Either you have to find a comic that explores the genre in a unique way (Deadpool) or, if you already have an established property, you have to find a director who’s going to add a stylistic flourish that gives that property a fresh feel (Thor: Ragnarok).

The Concrete art has me hoping we’ll get a little of both here. Let’s take a look.

I know a script is in trouble when the writer doesn’t make clear what the main character’s job is. When we meet Ronald Lithgow, he’s in a senator’s office writing down notes as the Senator speaks. Does this make him his assistant? A co-worker? Someone who works alongside the Senator and is merely keeping notes for himself? We’re not given a clear answer, and this becomes an issue throughout the script.

And, actually, it’s a problem a lot of new screenwriters have. It’s not that they don’t tell you what the main character’s job is. It’s that unclear details become a pattern throughout the script, leaving the screenplay feeling like you’re squinting at it through a set of foggy glasses.

Anyway, so Ron goes on a vacation with his good buddy, Michael, to do some hardcore rock-climbing. However, when their curiosity gets the best of them and they explore a cave, they find some terrifying rock creature aliens waiting for them, who knock Ron and Michael out, and then when they wake up, they’re in an alien rock cave lab, having been turned into giant rock creatures themselves.

Michael is killed – RIP Michael – but Ron escapes, and when a local town reports a Sasquatch-like creature hopping around the premises, the NSA swoops in, and an evil dick named Joe Stamberg, brings Ron to an NSA lab so he can study him. It’s there where Ron meets the beautiful Maureen, a scientist who has a jonezing for rock men. Ron seems perfectly fine with being treated like a guinea pig for some reason, but breaks out when it’s revealed that Maureen has been removed from the project.

Once out and spotted, Ron becomes an instant celebrity, and that’s when Stamberg realizes he can make some money off this thing. So he pulls a George Lucas and and sells Concrete’s rights to comic book and toy companies everywhere. Concrete starts making appearances on news shows. Everyyyyyybody loves Concrete.

But Stamberg wants to take things further, and when there’s an incident at a mine where dozens of miners are trapped, he sends Concrete there to save them. Pump up his celebrity even more. But Concrete screws up the dig and, as a result, men die. Is the Concrete love now over? Will the world turn against him? And if so, what else is there left for a man trapped in a 12 foot tall body made of rock?

Right, so, I’m not going to mince words. This was a mess. I’m guessing that while Chadwick was an accomplished comic book writer, this was an early foray into screenwriting. There were too many Screenwriting 101 problems.

For starters, the celebrity sequence – where Concrete becomes a worldwide celebrity – it lasts 30 pages! I mean, I can see a 7 page montage TOPS. But it just went on and on and on. And this isn’t what screenplays are made for, giant 30 page sections with good vibes and zero conflict. You can’t be that friendly for that long without the audience getting bored. This comes down to a basic understanding of how screenplays are paced. It’s okay for good things to happen for a scene or two. Maybe even three. But then you got to start throwing conflict at the main character.

And that was another problem. Ron had zero issues with being imprisoned by the NSA. His attitude was, “Yeah, whatever you need.” And since that section ALSO went on for a long time, that was another area that got boring.

Then there was Ron himself. For such a cool looking character, there’s nothing going on with him. One of the things you need to do early on in a script is establish who your main character is BEFORE THE TERRIBLE THING BEFALLS HIM. If we don’t know who he is, then what happens to him feels empty.

I’ll give you an example. If we’d been shown, early on, that Ron was always getting overlooked, that he wanted more attention, that he was invisible at work, NOW when he becomes this huge celebrity, it has more weight. Because it’s tied to something that we’ve established he wanted. Then you can go into a “be careful what you wish for” story.

And I’m not saying you had to go that route. I’m saying you had to go SOME route. And this script gave us no route early on. By not establishing who the hero was… EVER… we never knew what the main character’s journey was supposed to be.

The problems don’t stop there. Concrete doesn’t encounter his first opportunity at heroism – saving people in the mine – until page 80!!! This is a superhero movie. The first big heroic act should not be occurring 80 pages into the story. Sure, if this is a more cerebral character-based superhero movie, I’d understand the lack of big set pieces. But we just established there’s nothing going on with this character. I don’t have any idea what I’m supposed to be thinking about him. As far as I can tell, he’s a guy who’s relatively happy to have been turned into a giant rock man. Which is a leap you have to explain to the reader. But we never get any explanation.

To be fair, an entire superhero renaissance occurred between the time this script was written and today. The bar has been raised considerably. If they’re going to still develop this project, I would go 100% away from the celebrity stuff and focus more on the turmoil of what it’s like for this man to live like this. Those are the most arresting images from the comics and the far more interesting theme. This long drawn out rise to fame is the last thing that’s going to interest people about a rock dude.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whatever big themes you’re exploring in your movie, you have to build a bridge between those themes and your character. There’s no reason to make celebrity a giant theme in your story if your main character doesn’t have opinions or conflict about celebrity. A big component of Iron Man, for example, is his ego. So when he makes the decision to tell the world he’s Iron Man and become this celebrity, that decision is tied to his character in a clear way.

Genre: Mystery

Premise: (from writer) The host of a popular skeptic/debunking radio show works alongside a reluctant psychic in a last ditch attempt to find his missing daughter.

Why You Should Read: I was ecstatic when I found out an earlier draft of this script placed top 10 in the 2017 Launch Pad Feature Competition. From there, the contest organizer sent the script to a producer looking for material and after the producer read it, he sent it to a manager he knew. The manager got back to him within 24 hours to say he loved the story as well and wanted to meet me. Momentum, momentum, momentum! I owe that manager and producer a ton of credit, because together we shaped the story into a project we felt the industry would consider. — My manager had a plan to keep the reads exclusive, targeting select production companies, so why am I making the script public, submitting to AOW in hopes of getting a review? After the screenplay was sent up to the owner of a fairly well known production company and interest expressed, my manager vanished. This was in late July and to this day I have no idea what happened, I hope it wasn’t something catastrophic. In the meantime, it’s back to square one for me and I’m proceeding as though I’m unrepresented. I’d love to know what the Scriptshadow community thinks of the story – and more importantly – if they’d pay to see the actual film. Also, I can’t lie… having struck out in two previous AF attempts, the competitor in me seeks to earn that elusive “worth a read” my first ever submission – The Telemarketer – failed to produce.

Writer: Jai Brandon

Details: 119 pages

We have a variety of formulas that result in success in the movie business. Superheroes. Underdogs. Biopics. Monster-in-a-box. In the novel world, there’s one. MISSING GIRL! Hell, even if all you do is include the word “girl” in your title, you’ll sell 10,000 copies. And, for the most part, when this formula is transferred into the movie world, it works as well.

Gone Girl. The Girl on the Train. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

It makes perfect sense when you think about it. We are hard-wired to worry about helpless people placed in dangerous situations. And after we hear about one of these scenarios, we don’t feel at peace until we find out that the missing girl is okay. Even if it’s just a made up story!

There is a significant trick involved in getting these stories right, though. And I’m going to share that with you…. after the synopsis.

40-something Chace Clay is popular radio host at a local news station. But while he’s got his professional career on point, his personal life is a mess. He’s got an ex-wife, Lori, he’s always bickering with. He’s got a current girlfriend, Reesa, who’s a tinder box ready to explode. Luckily he has his beautiful little girl, Emily, to add some balance to his existence.

However, that balance is rocked when Chace’s babysitter loses Emily. Chace races home and soon cops are swarming the premises, trying to figure out how a young girl can just disappear. When they can’t find her, the community sets up a search in the local woods, and it’s there where Chase meets the mysterious Amari, a local African-American janitor with a psychic gift. Now’s the time I should tell you that Chace hates psychics. In fact, he lost his entire childhood with his brother when a psychic convinced their family that his missing brother was dead. 15 years later, the adult brother showed up at their door. It turns out a local creep had kept him locked in his basement for a decade. So, yeah. It’s safe to say that Chace doesn’t trust this guy.

However, it’s not like Chase has any leads. All the people closest to him passed their polygraph test. So he needs to think outside the box. Amari joins Chace, who suspects another psychic may be involved that he recently humiliated on his show. Chace thinks she may want revenge. The lead does bring them to the woman’s adult daughter, who claims she saw Emily earlier in the day.

This sends Chace and Amari on a deep dive into everyone Chace knows. But when the investigation turns around and points the finger at his current girlfriend, Reesa, everything gets thrown out the window. At a certain point he realizes he’s too close to judge anything objectively, which means he’ll have to lean on the one person he trusts the least, Amari.

We’re going to start at the beginning here. And I send this advice out with love, of course. I know how hard Jai works and I know how long he’s been at this. A title page in a unique font tends to be a red flag. NOT ALWAYS. But seasoned Hollywood readers will treat it as such. Also, 120 pages tends to be a red flag. NOT ALWAYS. But seasoned Hollywood readers will treat it as such. Especially when you’re writing in a genre where it’s easy to keep the page count down. This isn’t Legends of the Fall. It’s a mystery thiller. So right away, you’re raising two red flags. And I’m fine if a writer says, “You know what? I don’t care. I’m going to stand by that.” I just like to remind writers that in a profession where you don’t want to tweak the person determining your fate in any way, it’s best to control the variables that you can control.

Onto the story.

Whispers from the Watchtower is a mostly competent mystery-thriller. Both Chace and the daughter are set up well, which is the most important thing to get right, since that’s the emotional through-line of the movie. As long as we want to see Chace save his daughter, the plot is going to work.

I also like how the only way Chace can accomplish his goal is to team up with someone whose profession he fundamentally rejects. We’ve got that built in conflict there, which ensures that there’s going to be tension whenever these two are together. That’s important guys. If you don’t add story components that add tension to scenes, you’re going to have a lot of flat scenes. This is why teaming up two people who dislike each other is such a popular movie trope.

As for the plot, I found it to be above average. The challenge with these missing girl plots is that they’re so common. So the audience is way ahead of you unless you’re throwing something out there they’ve never seen before. And that’s my first beef with “Whispers.” The “strange attractor” to the story – the thing that’s supposed to make it different – is the psychic angle. However, the psychic stuff didn’t play into the story that much. By the end I was convinced Chace would’ve found his daughter without Amari, which left me wondering what the point was of adding a psychic to begin with.

That leads to the “significant trick” I promised you before the synopsis. In order to make any common movie scenario work, you need to add something fresh. The common scenario here is a missing girl. So what are you adding to that that’s new? With Gone Girl, they used an unreliable narrator that resulted in a huge twist. With Prisoners, they focused on false imprisonment and torture of the person our hero THOUGHT was the kidnapper. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo was insanely original with its unique setting, weird titular character, and Nazi connections. Even The Girl on the Train (great book, bad movie) did a deep dive on alcoholism and how it turned its hero into a narrator even she couldn’t trust.

Whispers From the Watchtower adds this in the form of the psychic element, which I was excited about. But it doesn’t deliver on the promise of that premise. Amari’s skill set kicked in when it was necessary for the plot, and was pushed aside when it wasn’t. I don’t know how to describe it. I guess I felt that Jai never committed to Amari’s “power.” Amari could have easily been a really good detective and I’m certain these two would’ve solved the case in the same amount of time.

The script also has some clarity problems up top. Chace’s personal life was unnecessarily complicated. In an early scene, he charges into a motel room where he’s yelling at, I think, a pimp, who’s got this, I think, hooker with him, Reesa. I didn’t know who Reesa was at the moment. But later on she shows up to take care of Emily and I’m thinking, “What the hell is going on here? He’s letting hooker girl take care of his daughter?” Then later, we learn they’re sort of together, but going through a rocky period. Or something?

Then we learn there’s another woman in the movie, Lori, who’s either his wife or ex-wife depending on which part of the script you’re reading. At one point Chace promises Reesa that he’s going to get divorced from Lori (which would make Lori still the wife). However, later, when Reesa is brought to the hospital, the doctors are referring to her as Chace’s wife.

I went back to the earlier scene when Chace tells Reesa he’s getting a divorce and I thought, “Oh, maybe he’s telling Reesa he’s going to divorce HER.” But to be honest, I’m still not sure. The thing is, this is the kind of stuff in a script that a reader should never have to think about. This is the “given” stuff. If I’m easily confused about relationships or who characters are to one another, the script is in major trouble. Professional writers don’t make these mistakes.

I think Jai could add some simplicity to his writing, particularly in the first act, where a lot of information is coming at the reader and it’s therefore easy to get confused. And I’d ask if he could go deeper with the psychic stuff. That’s your strange-attractor so if you’re only half-committed to it, I don’t think it’s going to fly. Still, this genre is a tough sell. I don’t want to send Jai down another lengthy rewrite when I know they don’t make these movies anymore unless they’re high profile novel IP. A sale can happen if the execution is amazing. But even the professionals have trouble with “amazing.” So I don’t know. I don’t want to see a writer pushing something with issues instead of working on something new and exciting with the additional knowledge they’ve taken from this experience.

Script link: Whispers from the Watchtower

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This might seem like a silly thing to highlight. But I liked that when someone on the television spoke, Jai simply put (TV) next to their name. I’m so used to “proper” screenwriting techniques, such as the debate of whether to put “V.O.” or “O.S.” in situations like these, that I didn’t realize a WAY clearer option is to simply put (TV) there.

NEWS ANCHOR (TV)

…Earlier today an Amber Report went out…

Welcome to the script that makes “The Wolf of Wall Street” look like “We Bought A Zoo.”

Genre: True Story

Premise: A look at one of the craziest rock bands ever to grace the stage – Motley Crue.

About: The adaptation of the Motley Crue biography, “The Dirt,” is a project that people have been trying to push through development for years. In fact, Rich Wilke’s script was on the inaugural Black List! It’s since seen many starts and stops. However, the bottomless money pit known as Netflix finally grabbed the rights and plans to convince Chris Hemsworth to play the lead. The debaucherous world of band pics hasn’t been tested in the current Hollywood climate, so if the movie hits, expect the floodgates to open for Van Halen, Guns and Roses, Def Leppard, and my personal favorite, Poison. Interesting tidbit here. “The Dirt” was written by geek-to-player legend and writer of “The Game,” Neil Strauss.

Writer: Rich Wilkes (based on the book by Tommy Lee, Mick Mars, Vince Neil, Nikki Sixx, and Neil STrauss)

Details: 123 pages

I’m just going to tell you right now. If you’re even the least bit prudish, don’t read this review. There is no way to summarize what happens in this story without getting XXX rated. If you’re okay with that, read on. If not, prepare for a script so scary, no one has the balls to make it.

There’s no easy way to summarize “The Dirt.” Its narrative – if you can all it that – consists of jumping back and forth between each member of the 1980s hair band, Motley Crue, before they were famous, after they were famous, and during their fame, in no particular order, as we watch them go through the highest of “highs,” and eventually the lowest of lows.

First there’s lead singer, Vince Neil. Vince was the ultimate ladies’ man. He was paying child support before he even got out of high school. Vince quickly figured out that the best way to get even more girls was to be in a band.

Next came Nikki Sixx, who played bass. Nikki was a troubled kid from the hood who routinely got beaten by his mother’s many boyfriends and husbands. He finally escaped that life to join Motley Crue, where he quickly became a hardcore heroin addict.

Next was Tommy Lee, the member of the band the average person is most likely familiar with. Tommy grew up a suburban kid and therefore wasn’t as susceptible to debauchery as the other members at the time. Well, unless you count his addiction to having sex with Hollywood celebrities.

Finally there was the most mysterious member of the group, guitarist Mick Mars. Mars was the old man of the group, having attempted to become rock-star famous for a decade before joining Motley Crue. A noted recluse, Mars would later find out he had a rare debilitating bone disorder that would slowly turn his entire skeleton into the equivalent of concrete.

The Dirt opens up on a Motley Crue party where Tommy Lee is performing oral sex on a girl in the middle of the room, which results in her squirting as she orgasms, where Nikki Sixx is waiting to catch the erupting fluid in his mouth. Hey, I told you to turn away from this review, didn’t I?

Oh, don’t worry. It gets worse. There’s a scene where the Crue runs into Ozzy Osbourne at a pool party, who’s desperately looking for a bump of cocaine. The band proclaims they’re out, which isn’t good enough for Ozzy, who grabs a straw, gets down on his knees where a line of ants are walking, and snorts up the line of ants instead.

The most difficult-to-read sections of the script are Vince Neil’s. Neil would go on to kill his best friend during a drunken beer run, while also causing permanent brain damage to the two teens he ran into. Vince somehow gets off with only 30 days in jail, and we later show him at an after-party, having sex with five different girls, lined up one next to the other, while cutting back to a hospital where one of the girls he gave brain damage to is learning how to walk again in physical therapy.

What’s amazing about this script/story is that it covers all the angles in excruciating detail. You get the good, the bad, the weird, and everything in between. There’s a midpoint multi-monologue from all the band members about what it’s really like being a rock star that has to be the most insightful dive into the lives of this profession I’ve ever read. I found it particularly interesting how quickly they got sick of it. That despite all of the perks – and the perks were great – that it was still a job that required you to be “on” every night to a new audience who had just paid a ton of money to see you and who had been looking forward to this all year. And you’re sick, and you’re tired, and you just sang these stupid songs the last 20 nights in a row, and your hearts racing out of your chest to the point where you think you’re going to die because you’ve done SO. MANY. DRUGS. and you still got to be on. You still have to give them the show of their life.

I also loved the visuals that the writers included. One of the main themes of the movie is the “machine,” which is a “rock star machine” that every band must sacrifice themselves to. But instead of only referring to the machine, we see it. It’s big and monstrous with hundreds of different levers and walkways, like a satanic version of something you’d see in a Dr. Seuss film. And we see how, each time a band makes it past a level, they’re placed on a higher, faster, more dangerous level. And the entire machine is dedicated to chewing you up and turning you into meat. It’s a tremendous image and a powerful metaphor.

I don’t know what else to say. This script is fearless. I mean where else are you going to read this line: “We ROCKET IN on Vince’s furiously pumping ass and suddenly… WE’RE INSIDE VINCE NEIL’S TESTICLES.”

I suppose if there’s something to learn from this script it’s: This is how you avoid writing characters who have the potential to be cliche. You write them by subverting the cliche and by adding detail that nobody else in the world would’ve thought of. The newbie writing four rock stars is going to give them very few flaws, if any. They’re going to focus on all the good stuff – the fame, the girls, the drugs. They’re not going to torture their characters like Strauss and Wilkes do. Seeing Vince try to retain his rock star edge after killing his best friend and ruining the lives of two innocent people is both disgusting and heartbreaking. Seeing someone learn they have one of the worst diseases in the world is a detail no newbie is going to think of.

And even the “cliche” stuff, like Nikki Sixx being a heroin-addict, is saved by the level of detail given to the addiction. Sixx goes on drug trips that rival, and in some cases even surpass, those we saw in Trainspotting. DETAIL and SPECIFICITY is the way to make a reader forget all about cliche.

Rarely do I read an adaptation of a book and want to go back and read the book. What’s the point? I just read the streamlined version. But “The Dirt” is one of the few times where I have to now read the source material. You can tell they had to leave a ton out. And I can only imagine what else I’m going to find inside the Motley Crue time capsule. Hell, maybe I’ll even go listen to a few of their songs.

Okay, maybe I won’t go that far.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This might be the first script I’ve ever read where there’s no narrative – almost the entire script is told in vignettes – and yet I never lost interest. Why? Because these characters were so damn fascinating. This goes to show the power of character creation and how you should always prioritize compelling characters FIRST and plot SECOND.