Search Results for: F word

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from Black List) After a shooting at a police funeral by a suspected militia member, a recluse ex-cop and fellow militia man must interrogate the suspected gunmen in his own militia before copycat attacks start a nationwide war between cops and militia.

About: This script finished on the 2015 Black List. The film will star current Walking Dead villain, Jeffrey Dean Morgan. The writer, Henry Dunham, will also be directing. Dunham first made waves with his short, The Awareness, which you can watch here.

Writer: Henry Dunham

Details: 105 pages

Just want to give everybody a heads up. Yet ANOTHER female John Wick project is going into production, this one starring Alias vet, Jennifer Garner. The script is being written by Chad St. John, whose Scriptshadow interview you can check out here. Not going to mince words, guys. If you’ve got a female John Wick script, ya better finish fast. I sense that the end of this trend is coming, especially with the so-so box office of Atomic Blonde.

On to today’s script, which actually contains an ORIGINAL premise. Imagine that. A concept that isn’t following any trends but is rather blazing its own trail. I’ve always been fascinated by the militia. We basically allow people in our country to come together and form their own personal armies. How is that okay?? It was for that reason that I picked Militia up. Let’s find out if it rewarded my curiosity.

40 year-old Gannon lives out in the wilderness. He’s in the midst of smoking a deer for dinner when he hears automatic gunshots in the distance. These gunshots are followed by three explosions. Gannon immediately gets on the phone with a dude named Olsen and the two agree to meet at “The Safe House.”

That safe house is a reclusive lumber warehouse where Olsen and Gannon are soon accompanied by a trickling-in of militia members. There’s Beckman, the techy of the group, Morris, the giant Alpha Male with a chip on his shoulder, Hubbel, a slovenly mountain man, Keating, a deaf-mute, and Noah, the only guy here who looks reasonably presentable.

As the group listens in on the radio, they learn that someone has attacked a cop’s funeral and shot up a good 20 cops in the process. This is bad news because the first people they’re going to suspect in this shooting is the militia. And that’s where the meeting begins – how to make it clear they weren’t involved.

However, when they check their supplies and learn an automatic rifle and several grenades are missing, they realize they WERE the ones involved, and now it’s a matter of smoking out the guy who did it. Gannon takes the lead with the interrogations, convinced that the antagonistic Morris is their culprit.

But it quickly becomes clear that not everything is as at seems. And when word comes in that there have been TWO MORE major militia attacks in neighboring states, they realize that this is way bigger than just one guy. In the end, it’ll be up to Gannon to figure out who’s lying and who’s telling the truth before the police find them, raid the warehouse, and kill them all.

UGH!

I so wanted this to be great! I loved this setup.

So here’s a great tip for screenwriters looking for a big concept that can be made on the cheap. As we’ve discussed before, when your script is cheap to make, you increase the number of potential buyers exponentially.

To do this, start with a really big idea. It can be anything. A giant monster. A mega-quake. A nuclear war. Whatever. But don’t build the story around the actual subject. That’d be expensive. Build it around characters who are affected by the subject.

What this does is it makes your movie feel big even though it’s small.

That’s what Dunham does here. There’s a big attack on this cop funeral, but we don’t see a frame of it. We hear it. But we don’t see it. Then, the entire movie takes place in a warehouse with these characters trying to figure out which one of them perpetrated the attack.

Do you know how cheap it would be to make this movie? You could shoot it in 2 weeks. And it still FEELS BIG. That’s really smart writing there.

Another thing I liked about this script was that it was a SITUATION. What I mean by that is, we don’t see the attack, watch someone run away, show the cops prepare to catch them, show our attacker hide out, meet a love interest, try to move to the next safe area, get into a chase scene, etc., etc.

That’s not a situation. That’s a series of events.

Militia is a situation. A bunch of dudes in one place. One of them killed some cops. The leader has to figure out which one of them did it. Every person who walks into this theater is going to immediately understand what this movie is about. What the setup is. What the rules are. It’s a clear situation.

Not that non-situations can’t work. Yesterday’s film, Good Time, wasn’t a situation and it was a great flick. But situations tend to work really well for feature films. So if you can think of a good one, write it. Other situation-films include The Shallows, 10 Cloverfield Lane, Saw, The Hateful Eight, The Thing, The Wall, Birdman and The Martian.

Yet another great tip to take away from Militia is the mid-point RAISING OF THE STAKES. Remember that when you go into the second half of your story, you need to make things feel bigger somehow. If they stay the same, people are going to get bored. Especially in a movie like this, where you only have one location to work with.

So the midpoint news that it wasn’t just this one funeral attack that happened, but that there was a coordinated attack against cops across three separate states? That’s when I was like, ooooh, this is good. The movie was growing beyond its original setup. That’s always a good thing.

But all was not perfect with Militia.

My big issue with it was that the character-to-character interactions felt a little… phony. I didn’t get the sense that the writer really understood what militia men were like. And this is a common issue in screenwriting. You pick an idea because you like it, but you don’t know anything about the actual subject matter.

So you have a choice. You can do some research and combine it with what you’ve learned through similar movies that you’ve seen, or you can really do the hard work. That means doing a fuck-ton of research. That means finding and locating an actual militia member and talking to them. Learning what their day-to-day life is like.

Nobody likes to do this. So the more common route is the former. And, unfortunately, when you do the former, there’s a lack of authenticity to the proceedings. And I’m not saying it was insufferable here. Some of the interactions felt real. But there were enough moments where I wondered, “Would this really be happening this way?” that it affected my enjoyment of the story.

With that said, I love this setup and I have a feeling that with some rewrites, these authenticity problems can be fixed. So I’m going to recommend Militia. It’s a fun script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you really want to make your descriptions pop, use analogies. When you have a guy with a deep voice, you don’t want to say, “His voice is deep and throaty.” That’s boring. Do what Dunham does. Here, he describes mountain man Hubbel’s voice with an analogy: “Every word from Hubbel sounds like gravel being raked.”

A script without a theme is like a photograph without a subject. The picture can be well-composed, colorful, sharp, and yet the experience of looking at the photo feels empty. You get no sense of what the photographer was trying to say with the image.

“Trying to say,” is a nice way to define theme. When you write a story, you should be trying to say something. You don’t have to. But it helps fill in the emptiness. It helps give your story meaning.

Today, I want to talk about how to find your theme. And not just for your own projects. When you break into the big leagues, being able to discuss theme in a pitch room will be one of the determining factors for you getting the job. When you’re angling for that million dollar Emoji Movie assignment, you better have an idea of what your theme is going to be going into the pitch or I promise you, you won’t get it.

Despite the term being one of the most abstract in the craft, theme isn’t as difficult to identify as you might think. In fact, most of the time, it’s right under your nose.

A few weeks ago, Steph Jones sent me her logline for a consultation (the script was also a part of last week’s Amateur Offerings). Her script was about two fame-seeking millennials who start a fake travel adventure blog. Going off that one-sentence breakdown, let’s see how we figure out the theme.

The driving force behind Steph’s story is clearly fame. That’s what these characters are looking for. Therefore, our theme should revolve around celebrity. So maybe the theme is about our culture’s obsession with celebrity without actually having to earn it, and the ramifications of that.

Keep in mind that simple/universal themes resonate best. And that a good theme teaches the characters a lesson after it’s all over.

Continuing on, let’s look at yesterday’s script, Murder on the Orient Express. Here’s the logline: “When a murder occurs in the first class cabin of the Orient Express, a world renown detective must figure out which of the travelers committed the crime.”

This one is tougher as the logline is too broad to imply any obvious themes. However, if you were writing this script yourself (spoilers!), you would know that the murdered man is an escaped killer, and that the travelers have decided to kill him for it. This opens up a more obvious theme, which is that of vigilante justice. If a man has done something inarguably horrible, is it okay to take justice into your own hands, or do you gamble on the risky nature of official justice, where the man might go free? This is one of the most common themes in film. You see it in Westerns, in superhero movies, and in revenge thrillers (John Wick).

Okay, let’s up the difficulty level. Dunkirk: “An army of 300,000 men, trapped on the beach, desperately await rescue while a surrounding German army decides whether to attack or not.”

War allows for the exploration of many themes. So it’s not like you can wrong here. But with the key plotline focusing on one soldier’s willingness to do anything to escape the beach, you could argue that the theme of Dunkirk is, simply, selfishness. At what point does sacrifice give way to looking out for number one? Indeed, this theme is present throughout many war movies.

Since this is Scriptshadow, we can’t go through an entire Thursday post without a Star Wars example. But let’s make it tough on ourselves. We’re going to find a theme for Rogue One: “A group of misfit criminals must join together to steal the plans of the most dangerous weapon in the universe.”

Hopefully you guys are getting a feel for this now, so before I offer my theme, go ahead and try to figure this out on your own. I’ll wait… Okay, so we have a group of people attempting to steal something. Normally, these people operate on their own. So this one is actually pretty easy. The theme is the power of the group over the individual. In life, one person can only achieve so much. But together, the possibilities are infinite.

Remember, themes should have consequences for the characters who deviate from them. Or, at the very least, the threat of consequence. So if one of the characters in Rogue One chooses an action that pits himself above the group, he should pay for it.

Okay, let’s end on the toughest one yet. It’s so tough, I’m not even sure what the theme is yet. Gone Girl. Here’s the IMDB logline: “With his wife’s disappearance having become the focus of an intense media circus, a man tries to prove that his wife is inexplicably responsible for what has happened.”

Usually, when the theme for a movie isn’t obvious after you’ve watched it, that’s a bad thing. It means the message didn’t come through clearly enough. And it may be why, while Gone Girl is considered a good film, it’s not one that’s remained in the public conscious. That’s why theme is so important. A well-executed theme helps a movie stay with someone for many years to come.

But I’ll give it my best shot. I’d say that the theme of Gone Girl is our society’s need to try people in the court of public opinion. You’re guilty until proven innocent. What I find interesting about this and similar themes is that while they shine a light on society, they don’t hit the audience on an emotional level. That’s something to keep in mind when you choose your theme. Do you want to make a statement about society or do you want to make a statement about the individual? The former gets critics frothing but the latter stays with audiences longer.

Now bust out your latest script and figure out the theme, dammit!

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations, which go for $25 a piece or 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. And as of today, all logline consultations come with an 8 hour turnaround time. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Genre: Action/Adventure

Premise: The military contracts a disgraced Harvard professor who believes in dragons to escort them to a mysterious island where the mythical beasts potentially still exist.

About: What else is there to say? It’s another Max Landis script, baby. The one writer still making huge spec sales. This one, to my knowledge, has not sold yet. But if anyone has any updated information on that, let me know.

Writer: Max Landis

Details: 120 pages (Dec 2014 draft) Second Rewrite

Max Landis really likes orcs.

And dragons.

And fairies n stuff.

By the way, I finally figured out why the trailer for Landis’s Netflix flick, “Bright,” begins with that uncomfortable fairy-beating sequence. I realized that a meeting took place within the Netflix brain trust…

“How do we show that this is the kind of fantasy movie Hollywood can’t make?” So they had Will Smith beat the shit out of fairy, the message being: This ain’t your grandfather’s fantasy flick.

Was that choice a success? No.

But that’s what’s great about Netflix. They’re okay with taking chances. And chances often fail, as I’ve discussed in a recent Scriptshadow post.

So let’s get to today’s script, because I think there’s a huge screenwriting lesson we can learn from it. But before I tell you what that is, let’s dive bomb, dragon-style, into the plot…

Terra Obscura starts with one of the most traditional first acts you’ll find in a movie like this. Which was surprising since Landis is such an anarchist. Adam Burns just got fired from his Harvard professorial job after an interview of him saying he believes in dragons goes viral.

After his girlfriend reams him out for deep-sixing his career, Adam is kidnapped off the street by men who’ve watched too many movies, since they throw a bag over his head then yank him into a van. They then throw him on a helicopter, informing him that they’re going to an island where a Russian sub thats’s been programmed to launch a nuclear attack on the U.S. has crashed.

Adam makes it clear he doesn’t know why he’s here. “I don’t know what’s going on.”

“On the contrary,” the military official tells him. “You might be the only one who knows what’s going on.”

Cue our “HARD CUT TO” Predator helicopter moment. Oh yeah, this island they’re going to may contain… creatures of the magical type. That’s confirmed the second they fly over land when two dragons that would make Khallesi’s corset explode attack the Blackhawks.

Adam’s helicopter crashes and he and the men use a radiation meter to figure out where the marooned sub is. But on the way there, they run into orcs and fairies and Necromances and Dark Elves and other nerdy monsters. What Adam realizes is that the Russian sub may have been a ruse. Which means they’ve been lured here. But why? The answer may be much worse than a measly nuclear attack on the United States…

The first thing I noticed about Terra Obscura had nothing to do with Terra Obscura. Rather, it had to do with Skull Island and Ghostbusters. Strangely, two of the first three scenes in Landis’s script have helicopters arriving on an “invisible” island and giant monsters attacking them. After that, we flash back to show Adam getting fired from his job at a prestigious university because he yelled into a camera, “I believe in dragons,” then got fired by his boss after it went viral.

Both these scenes, almost verbatim, were in Skull Island and [the new] Ghostbusters. I see that this script pre-dates both of those films. So what does that mean? I remember Landis either worked on or was going to work on Ghostbusters. So maybe he wrote a similar scene there and they used it cause they had the rights? But I didn’t know Landis worked on Skull Island. And if he didn’t, does that mean someone just took this scene from Terra Obscura?

Of course, there’s a third possibility: None of us are as original as we think we are. Maybe these ideas are so obvious that everybody is writing versions of them. I don’t know. But I found that surprising. I was like, “I’ve seen both of these scenes already!”

There’s a bigger talking point I wanted to get into today, however. And it has to do with the fact that Bright got made and Terra Obscura (as of today) did not. Why is that?

BUDGET

Bright is set in the real world with actors wearing prosthetics. Terra Obscura is shooting in a jungle with a full slate of Lord of the Rings like creatures. In other words, it’s a lot more expensive.

I’m often asked by writers if they should write something big budget or small. The answer to this is more complicated than you’d think but I’ll give you the simple answer first. SMALL. Look at the data. How many non-IP giant-budgeted movies are made a year? Two? How many non-IP small budget movies are made a year? A LOT. So you’re increasing your number of buyers exponentially with a lower-budgeted script. Which is why Bright was kind of genius. It was a high-concept idea that was financially achievable.

However, there’s a growing belief that it’s so difficult to sell screenplays, you have to entertain the long game when thinking about which script to write. So if you want to write big-budget movies like James Bond, you write a James Bond-like movie, knowing that it isn’t going to sell. However, if people like it and you get buzz from it, you’re now brought into the Hollywood loop, and you’re in contention for assignment work on movies like that. So in that case, writing the big-budget idea was the way to go.

The point is, it depends on what your goal is. If you’re just trying to sell, Bright is the perfect conceptual blueprint. It’s a budget-friendly genre idea. But if you want to write for the Star Wars or Avatar franchises, write the best sci-fi fantasy script of the decade. Just know that you ain’t going to sell it.

As for the Terra Obscura script (which is the name of the island, if you were wondering), it was pretty good. It poses an interesting question for a script like this. Do you make your hero resistant or active? In the similarly set up, Aliens, Ripley is a boss. She’s all in right away. In Terra Obscura, Adam doesn’t want to be here at all. He’s scared. This is too much for him.

Both options have their pros and cons. When your hero is resistant, like Adam, he has somewhere to go as a character. It’s clear that there’s going to be an inner journey here. Him being able to overcome his fear will lead to him changing, which, when done well, results in a more impactful viewing experience.

However, in Aliens, Ripley is thought of as one of the best characters ever. And she was active and brave from the start. Why did that work? Well, Cameron decided to explore a different part of Ripley to show her growth. Both her distrust of the mission and her role as a mother to Newt became the backbone for her character growth.

And that’s the thing screenwriters forget. You’re not limited to one of those “fatal flaw” boxes. You can play outside the box.

Also, I find it dangerous to have a hero who’s too weak. Even if they’re eventually going to arc into a strong person, we’re going to be spending at least half the screenplay with them as a weakling. And audiences have trouble rooting for weaklings (not physical weaklings, but mental). That hurt my overall opinion of the script.

However, Landis knows how to keep a script entertaining. And whereas the Kong Skull Island plot points were visible from light years away, I didn’t know where this script was going. The Dungeons & Dragons creatures angle threw me off. And Landis’s love for that world resulted in numerous twists and turns I wasn’t expecting.

So Terra Obscura was just fun enough for me to recommend.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A trick for writing high-concept low-budget genre films is to utilize one fantastical element and place that element inside the modern-day world. What this does is it ensures that studios don’t need to create any expensive effects-driven worlds. They can shoot 95% of the movie in real world settings. Then, the one fantastical element (Orcs in Bright, or time travel in Primer) is what gives your script a big feel for a cheap price.

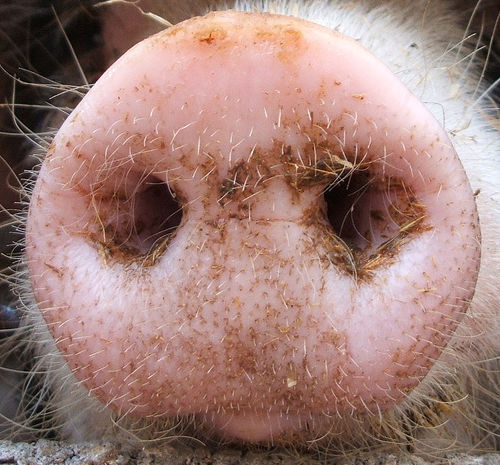

Genre: Horror/Comedy

Premise: When pipeline construction encroaches on its pristine Dakota Badlands territory, a giant prehistoric pig creature unleashes hell on a group of unsuspecting humans, who must band together in order to survive.

Why You Should Read: Longtime SS lurker here, ready to throw my script into the pit. Hellpig is a heapin’ helpin’ of action, gore and camp with a Sharknado tone, a unique monster and buckets of blood. Thanks to Carson and everyone for the opportunity and the reads.

Writer: Michael Harper

Details: 96 pages

It’s awfully funny.

Just yesterday I was watching Maximum Overdrive, the Stephen King directed film that was featured in the script I reviewed Wednesday. That film exists in the same universe as Hellpig. And despite being written by someone who doesn’t yet have a produced credit, much less 40 best selling novels, I gladly contend that Hellpig is better than that film.

How much better? After Scriptshadow’s own, Steph Jones, came up with the script’s tagline (“Go pig or go home!”), I’d say it beat the King debacle by a full lap.

But let’s be honest. Maximum Overdrive is hardly a cinema classic. Which means Hellpig hasn’t yet secured a passing grade. Let’s lift the cover off this pig in a blanket and see if it passes the ultimate test – the ‘squeal like a pig’ test.

45 year-old Walt Harvey is the most hated man on the planet. He’s one of those big game hunters who kills animals then takes douchey pictures with them before blasting the pictures all over social media. His latest conquest was a hippopotamus, which he and his camo-covered wife took down.

When rumor hits the street that the hippo was old and possibly fenced-in, however, Walt looks like a ten-ton asshole. The only way to redeem himself, in his mind, is to kill a 16-point elk, which he’s looking for in the heart of South Dakota.

Nearby, Harlan Hawes runs a Christian Rehabilitation Youth Academy that’s got four new members. There’s 17 year-old Max, who’s got a gambling problem, 17 year-old Kaci, who’s been suckin face with multiple men. There’s Doyle Choi, a 16 year old Korean pyromaniac. And 18 year-old Jed, a rich kid who steals anything he can get his hands on.

Harlan’s plan is to escort (force) them into the forest and rid their bodies of Satan. Little do any of these people know that a giant Hellpig is in the vicinity, burping out a new kill every few hours. Hellpig is not some made-up monster either, but a real pig that used to exist hundreds of thousands of years ago. Everyone assumed they went extinct. They were wrong. There’s a new brand of pepperoni in town.

Our hunters and rehabilitators eventually run into each other, and when Hellpig kills Walt’s wife, it’s game on. He’s getting revenge. Or maybe looking for fame. It’s hard to pinpoint which motivation drives him more. All our misfits know is that they want to get as far away from this killing machine as possible, but can’t because Lunatic Walt keeps taking them closer.

What Walt doesn’t realize is something everyone else knew the second they looked into this monster’s eyes: This is one piece of bacon that can’t be cooked.

What surprised me the most about Hellpig was how seriously Harper took the subject matter. You see the title “Hellpig” and you expect, well, Maximum Overdrive with pigs. But you can tell a lot of thought went into this. Three entire scenes are dedicated to the backstory of Hellpig.

Now you may say, “Carson, you tell us backstory is bad. Backstory slows the script down.” This is true EXCEPT when the backstory is interesting. Sure, if you’re telling me Mikey got a beating by Daddy’s hand when he used to come home late from school as a child, I don’t want to hear that. But if you’re telling me about a pig that used to be a fucking dinosaur that went extinct hundreds of thousands of years ago – I want to hear more of that.

I knew I was in good hands early when an oil pipeline subplot was introduced. This may seem pointless at first glance. But by adding that plotline, you’re telling the reader, “I’m not just going to give you 90 pages of a pig that looks like the devil tearing people apart. There’s going to be more to this.” And there was.

For starters, you know that old screenwriting tip everybody says you should do but nobody actually does? How you should be able to black out all the character names yet still know which character is speaking? In other words, each character sounds so distinctive that we don’t even need to see their name to know who’s talking? Well you can do that here.

Walt is always pissed off about not being taken seriously as a hunter. Max is always making some wise-crack or betting other campers about something. Kaci is always trying to get in Max’s pants. Harlan doesn’t say a single sentence that doesn’t include “God” or “Satan.” These distinctions created a legitimate variety of characters, and not just generic Hellpig victims.

Also, yesterday we focused on the power of conflict. There’s a major conflict lesson right out of the gate in Hellpig. These four teenagers have been FORCED to go to this Hawes Christian Youth Academy and participate in something they don’t want to do. Therefore, before we’ve even SEEN Hellpig, we ALREADY HAVE CONFLICT.

Beginner writers ask me all the time: How do you know the difference between professional and amateur writing? Well, it’s choices like this one. When you create situations that include conflict before the main source of conflict even enters the story? That means you know how to write a screenplay.

As far as negative feedback, I would encourage Harper to give us more of the teenagers. As much as I liked them, there wasn’t enough of’em. All the focus was going to Walt and his hunting crew. And while Walt was funny to carry all those scenes. So were the kids. Since the groundwork is already laid out, all you’d have to do is give them more screen time. I mean Doyle shouldn’t die before we even got to know him.

Otherwise, this was a really solid Amateur Friday entry. You guys continue to do a good job of finding the best material out of the scripts presented. Thanks a lot for that. It makes my job a lot easier.

To all of you I say… Oink. Oink Oink……. Oink.

Script link: Hellpig

[ ] No squeal at all

[ ] Barely a squeal

[x] Squealed like a pig

[ ] Squealtacular

[ ] Golden Squeal

What I learned: Once you’ve identified the location you’re going to place your story in, research that location to come up with plot points and set pieces that are unique to that area. This will help set your story apart from others. I loved that we were dealing with the oil pipeline, a South Dakota specialty at the moment. Or that we ran into an old Native American cemetery, South Dakota being rich in Indian reservations.

So maybe I was a little bit of an ageist yesterday. Picking on a script because it was written by a 22 year-old. The script had made mistakes, I claimed, that only a young writer would make. That was some proper-ass stereotyping I was doing. That’s not cool, Carson.

But it was true.

In revisiting my Maximum King reading experience, I further realized why the script had missed the mark. It was completely devoid of any conflict. The reason that tends to be a young writer mistake is that younger people haven’t experienced the pushback from life that a longer living experience gives you. You don’t truly realize how difficult life is until you’re thrust out into it and it does everything in its power to beat you down.

From the very first scene in Maximum King, conflict appears to be an afterthought. Someone comes to Stephen King and says, “Do you want to make a movie?” To the uninitiated screenwriter, you look at that and go, “So what?” To people who understand drama, they know that that’s the worst way you could possibly start a story. One of the most sought after and hard-to-get jobs in America – directing a movie – is just HANDED to our hero?? He didn’t have to do anything for it but exist??? That’s not drama. That’s boring.

But I’ll give you the moment that confirmed to me that this screenplay was screwed. I knew after this scene that the writer didn’t understand the concept of conflict. And since conflict is the whole ball of wax in screenwriting, the future looked grim.

The scene in question has Stephen King deciding he wants to hire AC/DC to score his movie. Why? Because they’re his favorite band. Had they ever scored a movie? No.

You would think, then, that this would be the perfect opportunity for conflict. Stephen King goes to his heroes, asks them to score his movie, and they say “No. We’re not movie composers. We’re a hard rock band. Go fuck yourself.” And Stephen King would then have to CONVINCE them to do it. The scene almost writes itself.

Instead, we get this…

“So you want us to—“

“Write an original soundtrack for the movie, back to front, yes.”

“And the movie is about—“

“Right, trucks— no, well, not just trucks but all machines, because a comet passes over Earth and causes all the machine to—“

“Sure, come to life.”

“Exactly.”

“Well shit, I guess I’m the fuck on board. I love your writing, and Brian is a huge fan of Carrie, so.”

Brian agrees.

“Great.”

“Great.”

Do you see how boring that scene is? Do you see how it could’ve potentially been a lot better had they told King no? I mean that early line is practically begging for a no. “And the movie is about…” “Right, trucks— no, well, not just trucks but all machines, because a comet passes over Earth and causes all the machine to—“ Long pause. “Dude, that doesn’t make any fucking sense. How the hell are we supposed to write music to that?” And King now has to convince them.

Nope. Didn’t get that.

So that’s today’s lesson. It’s simple yet powerful.

JUST SAY ‘NO’ TO YOUR HERO

Your protagonist will want a lot of things in a movie. He might want a raise. He might want sex from his wife. He might want to sell milkshake makers to fast food restaurants. He might want more attention from his parents. He might want to go with his dream girl to prom. He might want to explore an island he believes contains a giant ape. He might want his daughter to start eating dinner with the family again.

Say no.

Have all those people say no to your hero.

Because when you say no, that’s when things get interesting. That’s when your character has to work for it. And work means action, which leads to uncertainty, which leads to audience curiosity (“Is he going to succeed or fail!?”). And that’s when you’ve got us. Cause we have to stick around to see what happens.

The second someone says, “Yes?” None of that can occur. There’s no uncertainty at all. And that’s boring.

It should be noted that I’m not just talking about LITERAL “No’s.” I’m talking “no’s” in every form and fashion. An open door is a ‘yes.’ A locked door is a ‘no.’ An equation solved quickly is a ‘yes.’ An equation your hero can’t figure out is a ‘no.’ A surgery that goes well for your hero is a ‘yes.’ A surgery that goes badly, setting your hero back, is a ‘no.’

Your screenplay should be one giant series of “NO’S.”

I challenge you right now to go through your current screenplay, find a scene where your hero is allowed to waltz right through without any issues at all, and instead, add a “NO” to that scene. Throw a big fat hard NO into his face and make him work for that objective. I guarantee you the scene gets a lot better.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations, which go for $25 a piece of 5 for $75. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. If you’re interested in any sort of consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!