Search Results for: F word

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: When a resilient and clever astronaut gets stuck on Mars, he must use every trick in the book to get rescued.

About: The Martian is one of the most anticipated movies of the fall. It’s got a great story behind it, too. Andy Weir self-published the book when he couldn’t get any publishers to bite. When it still didn’t sell, he was devastated. But then, just when he believed the book was a failure, sales began to pick up. Good old word-of-mouth propelled the book into a phenomenon, and Ridley Scott and Matt Damon came on in one of those rare “fast-track” scenarios that all writers dream of. The Martian is adapted by Drew Goddard, who’s become one of the biggest screenwriters in the business. He wrote for Lost, Cloverfield, World War Z, Cabin in the Woods, and Netflix’s Daredevil.

Writer: Drew Goddard (based on the book by Andy Weir)

Details: 10/4/13 draft

Last year, I wrote an “Adapt This Book” post about The Martian. The consensus I came to was that this would be a tough adaptation. You have one character, all by himself, in a tiny tent, doing math for hundreds of pages. How do you make that interesting?

But watching the recent trailers, I was surprised to see just how GOOD this movie looked. That seems to be the consensus of everyone who’s seen the trailers. People are REALLY FREAKING PUMPED for this movie! And it’s a reminder of just how much of a mind-fuck this business is. Why is it only obvious in hindsight how cool a movie can be? Because the idea of being stranded on Mars isn’t all that original. I’m sure someone’s thought of it (or something like it) before. Yet it’s this simple idea that’s captured the world’s imagination, and will probably make The Martian this year’s “Gravity.”

But for our sake – that sake being “how good is the f’ing script?” – I wanted to know how they’d tackled those “book-to-script” issues that worried me so much when I read the novel. So, let’s take a look…

For those who know nothing about “The Martian,” it follows Mark Watney, who was left for dead on Mars when his team had to make an emergency evacuation after a storm threatened to destroy their rocket home.

Word gets back to NASA that Watney didn’t make it, and the world is devastated.

There’s only one problem. Watney is very much alive.

Watney, a botanist, knows that the next mission to Mars is in four years. Which means he needs to figure out how to sustain himself for that long, which includes finding a food source on a dead planet. In his words, he needs to “science the shit out of this.”

Meanwhile, NASA’s Mars satellites pick up movement on the planet, allowing them to realize that Watney is still alive. After freaking out, they start designing a plan to save him.

When word arrives on the Mars mission ship heading back to earth that Watney is still alive, they decide to go against orders, turn around, and save him, despite the fact that they have no way to get back down onto the planet and actually pick him up. Will they succeed? Will Watney live? Is this script any good? I would answer these questions but I’d probably be spoiling the movie for you.

Okay, so my first adaptation worry was that Watney was communicating through a written diary. That doesn’t work in movies. So for the script, they went the Avatar route and changed it to a video-diary. This is probably the easiest solution when it came to the adaptation.

The next problem was you had 50-60 page chunks of Watney doing math. How oxygen needed to be coagulated to stabilize nitrogen and how that helped grow potatoes. Thankfully, Goddard got rid of all that. Which probably wasn’t an easy decision, since it’s the heart of the book and what Weir prided himself on (the realistic approach to the science side of the problem).

I was a little surprised at just HOW MUCH of this they cut though. Goddard makes the bold move to jump exclusively from major plot point to major plot point, skipping all that personal “I’m lonely and stuck on this planet” stuff in between. For example, whereas it would take 100 pages to get from Watney’s tent blowing up to him going out to find the Mars rover, here in the script it would take about 12 pages.

If there’s a lesson to take away from this script, it’s that. Screenplays aren’t made to explore the nuances of an event. You’ll have time to sneak a few in there. But ultimately, you have to keep the story moving, and we see that here.

Another thing that really surprised me was just how much time earth gets in this adaptation. In the book, it’s all about Watney. I’d say we stay with him about 70% of the time, and then cut back to earth 30% of the time.

I remember worrying about this when reading the book. I wondered how you could stay on a guy in a tent for 20 minutes at a time. Goddard and the producers appear to have had the same worry. Back on earth, lots of huge plot decisions are being made (the main one being how the hell are they going to save this guy before he runs out of food), so I guess they figured if that’s where all the action was, that’s where they needed to be. This has left us with a new ratio of 55% to 45% in favor of the earth scenes!!

But my spidey sense tells me that when Matt Damon came on (this draft was written a year before he became attached) he likely ordered more Watney time, and that appears to be what the trailers suggest. Still, it was interesting to see the script go away from Watney so much, almost as if they didn’t trust the movie to sustain itself when we were just with him.

Another adaptation issue I worried about was time. As you’re no doubt tired of hearing me talk about here, I believe that URGENCY is one of the key components to making a script work. Most movies you see take place within a 2-week period, and there’s a reason for that. It gives the story a sense of “SHIT NEEDS TO BE TAKEN CARE OF NOW.” If a story drifts on for too long without anything pushing it, the audience gets bored and loses interest.

But the one thing I keep forgetting is that a story needs to be as long as it needs to be. If your main character is stuck on Mars? And our scientific limitations say that we can’t get to him for another four years? Well, then that’s the time-frame you have to work with. As long as it makes sense to the audience, they’ll go with it.

And I liked the way Goddard handled time in the script. He wouldn’t make a huge deal about the passing time. We’d simply cut to a title: Sol 37. Then a few pages later. Sol 49. It was very unobtrusive and, in a way, made it so you weren’t even aware time was passing. That was clever.

Another thing I noticed – piggybacking off of yesterday’s post – is how much humor plays a role in Watney’s character. Watney has a very casual sarcastic sense of humor about the whole ordeal, and just like the humor in M. Night’s The Visit allowed us to fall in love with those kids, the focus on humor here ensures we fall in love with Watney.

A lot of energy in the screenwriting community is spent on determining how much you need to worry about making your protagonist likable, and my response to that is always: It depends on the movie. If you’re writing a movie where a serial killer is your protagonist, it doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to make the guy likable.

But in a movie like this, where your main character is all by himself with no one to talk to and you’re asking the audience to care enough about him for the world to spend 10 billion dollars to save him, then yeah, he’s got to be likable in some capacity. And giving your hero a sense of humor is one of the easiest ways to do that.

I’m going to finish up by saying something controversial but it’s something I’m feeling stronger about every day. The self-published book is the new spec script. With Hollywood terrified to take a chance on anything original, the self-published success story is the best of both worlds. It takes no money on your end to write and put the book up online. And when it sells a lot of copies, Hollywood gets their “proof-of-concept” they need to pull the trigger on a sale.

I say that to encourage you guys to try different avenues to get into this industry. Ask yourself if your idea would work as a novel and, if so, consider writing it as one. Even if you only do it once, you’ll have something tangible to point others to. In a business where a lot of writers don’t feel like “real” writers because they haven’t “made it” yet, this small victory can make your profession feel more real.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When adapting a book, write out all the major plot beats in the story. In your script, you’ll hit those plot beats every 10-15 pages – so fairly frequently. Here we had…

1) Watney is presumed dead and left on planet.

2) Watney needs food – starts growing potatoes.

3) Watney needs to communicate with Earth, goes on journey to find Mars Rover.

4) Watney’s decompression bay blows up, destroying his tent and all his food.

5) NASA tries to send Watney a supply ship.

6) The supply ship blows up on launch.

7) The Mars Mission crew decides to turn back and rescue Watney.

And so on and so forth. While a lot of the introspective stuff in between the book’s major plot points is great for novel readers, it’s not necessarily great for movie viewers, who want the story to move quickly. Which is why you see so much of that stuff excised in the screenplay version of “The Martian.”

M. Night’s new film shocks with a bigger than expected opening. But is this a “visit” worth taking?

Genre: Horror

Premise: (from IMDB) A single mother finds that things in her family’s life go very wrong after her two young children visit their grandparents.

About: You’ve loved him, you’ve hated him, you’ve laughed with him and you’ve laughed at him. And whether you like it or not, the once pop-culture directing icon (The Sixth Sense, The Happening, Signs) is back with a new film. Yes, I’m talking about M. Night Shyamalan. Night has sunk so low in the eyes of the paying public that he’s been forced to play by Hollywood’s new horror-film rules: 1) Get a hall pass from Jason Blum. 2) Don’t spend more than a million dollars. But darnit if Night didn’t make the most out of the opportunity. While his movie didn’t win the weekend, it did finish with 25 million dollars, almost 10 million more than what was expected. It’s a huge win for Night. But is it a win for us?

Writer: M. Night Shyamalan

Details: 94 minutes

One of the quirkiest parts of my day-to-day existence is how much I think about M. Night Shaymalan’s career. I probably think about it (usually negatively) once every couple of days. Even if he hasn’t made a movie in years.

This probably reflects more on me than it does Night. But as a screenwriting obsessist, there’s a part of me that gets really angry at the fact that he’s still making films. Not because he makes bad movies. Every writer-director has their Grindhouse. But because he makes REALLY REALLY bad movies. Like bad enough that if 20 years from now Night revealed that, as an experiment, he had a 5th grader write “The Happening,” I wouldn’t bat an eye.

It seems, at times, that he’s so out of touch (placing “symbology” higher on the priority list than THE ACTUAL FUCKING STORY), that someone ought to take the proverbial keys from him and get him an Uber. To retirement.

I remember when Unbreakable came out, his first movie after The Sixth Sense. The world was so drunk on Night Fever that they went into that thing with Night-as-my-God colored glasses and came out believing they’d just seen Citizen Kane 2.

I tried to rally the “what the fuck did I just experience” troops to no avail. But the signs were there. The entire movie was an empty excuse to set up a twist ending that made little, if any, sense. That’s one of the signs of a bad writer – someone who ignores the story itself in service of trying to wow the viewer at the end.

While everyone told me I was crazy, I watched as the mistakes I saw in that film became more and more pronounced with each new effort (Signs, The Village, The Little Mermaid 2), and, in that sense, I haven’t been surprised at all at how terrible his movies have become. For those paying attention, this was inevitable.

Which brings us to The Visit. Now, I’m pulling a “before I watch” written intro, which means I’m writing all of this down before I go see this movie. What am I expecting? Despite attempts to avoid spoilers, I’ve heard spits and whistles saying this is Night’s best movie since his early days. But, honestly, I don’t believe it.

I think everybody’s just so used to garbage from this guy that anything not garbage is going to seem great. So with that uplifting attitude, off I go to watch the movie. Wish me luck!

The Visit follows 13 year-old aspiring rapper, Tyler, and his sister, 15 year-old aspiring filmmaker, Becca, who really really want to meet their grandparents, and so have convinced their mom to allow them to spend a week at their home.

The family hasn’t had the best go of it. Mom left her parents in a huff 15 years ago after meeting a guy and hasn’t spoken to them since. She married him, had Tyler and Becca, but he left the family five years ago and hasn’t kept in touch since.

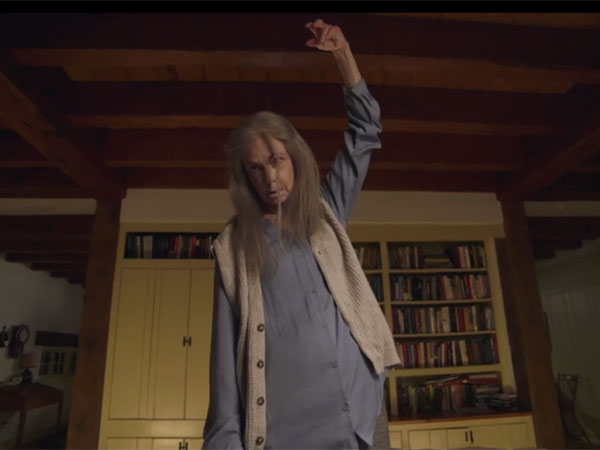

Told in a “found footage” type style, with the entire movie seen through the eyes of Becca’s TWO really expensive cameras, serious Becca and goofball Tyler start to notice their grandparents are a little strange. For example, “Nana” will just join in on “hide-and-seek” time wearing nothing but her nightgown and galloping around on all fours like a child.

With their mother busy on a cruise with her new boyfriend, the kids are only able to share their concerns about the grandparents in small doses. But when Nana starts trying to climb walls naked, that’s when bro and sis realize it’s time to jet. Too bad the grandparents catch on. And by then, it’s too late.

Let me start off by saying the crowd I saw this with really dug it. They were laughing their asses off. And if there’s one area The Visit should be praised for, it’s humor. Tyler, with his awkward rap obsession, along with the goofy vibe that both Nana and “Pop Pop” put out, give The Visit, at the very least, a quirky watchability that isn’t present in any of Night’s previous films, mainly due to the fact that he takes himself so seriously.

But the humor wasn’t just a win because it provided laughs. The humor brought us closer to the characters. That’s something screenwriters don’t talk enough about. Once you start laughing with characters, you feel closer to them (not unlike how you feel closer to people you laugh with in real life), and that makes you care more about what happens to them, which is key in any movie, but especially horror, where you want the audience to be engaged when the character encounters danger.

While this was a pleasant surprise, it couldn’t hide some of the movie’s clunkier issues. One of the stranger additives here was the “found footage” approach. For those who watch Night’s films, you know that Night’s directing style is THE OPPPOSITE of found footage. He likes to control every aspect of the frame, every camera movement, every line of dialogue, even down to the finite moves of the actors.

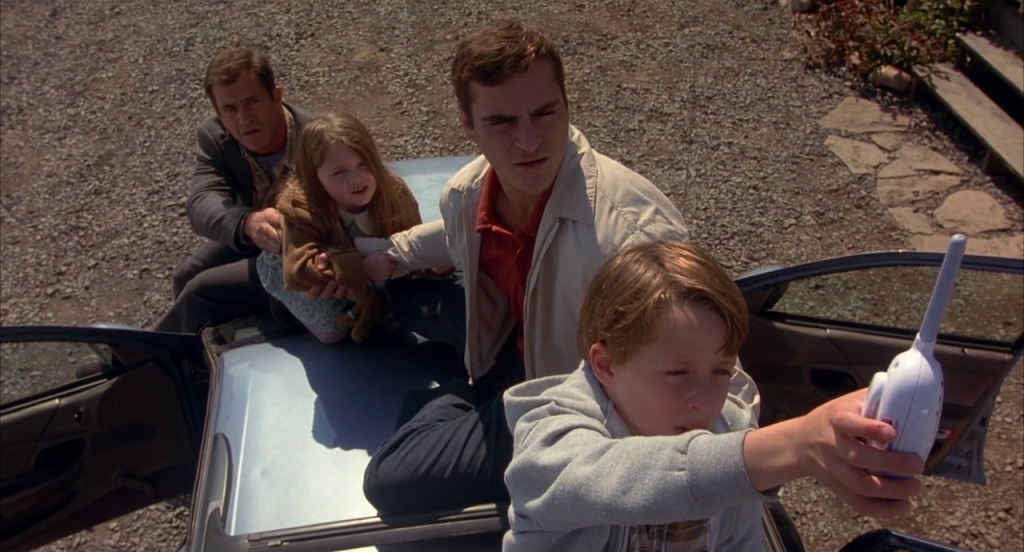

Remember the most manufactured scene in movie history? When the family in Night’s film, Signs, gets up on a car together and holds onto each other in order to get a walkie-talkie signal? That’s what Night loves to do.

Good “found footage” movies leave a lot of control up to the actors (Blair Witch), knowing that that’s the only way the footage is going to truly feel “real.” So when you watch The Visit, you can see that tug-of-war happening in every shot. The desire to create something organic and natural, ruined by the need to make every shot look, sound, and feel perfect.

I’ll give Night this though. It gives the movie a feel unlike anything else you’ve seen before. I’m still not sure if it’s a “good” feel. But it’s unique. And that counts for something.

Surprisingly, what saves this movie is the writing. Night has clearly spent more time on this script than his last 7 combined. And let me explain to you how I know that. Unfortunately, it’s going to require me to get into some big spoilers. So skip to the “What I learned” section if you haven’t seen the film yet.

Early on, we establish that mom hasn’t spoken to her grandparents in 15 years. She hasn’t even spoken to them for this trip. Everything was set up through the kids. We later find out why this plot point is needed. When the kids point out their grandparents in the yard over a late-movie Skype session, the mother’s face goes white. “Those aren’t your grandparents” she says. It turns out they’re a couple of escaped mental hospital patients posing as the grandparents.

In other words, if Night hadn’t written in this “I don’t talk to my parents anymore” plot point, there’s no film. The mom would’ve been able to talk/Skype with the kids AND the grandparents at the same time, immediately exposing them as imposters.

That gives the movie a bit of a “held together by popsicle sticks and rubber bands” feel to it, but there’s just enough there to make it work.

Now in the past, Night would’ve left it at that. And it’s indeed a fun twist that would’ve worked just fine. But what Night does here is HE MAKES THIS PLOT POINT WORK FOR THE STORY. Specifically, the whole reason that the daughter wants to meet her grandparents is to help repair the relationship between them and mom.

Between scares, Becca is asking her grandmother and grandfather about what happened. Why did the family fall apart? It becomes a major part of the story. This way, when the twist happens (they’re not the real grandparents) it doesn’t feel cheap, since Night milked the most of the storyline that allowed that twist to happen. That’s good writing!

Unfortunatley, I’m left wondering how long this new M. Night aroma will last. He’s FINALLY made a solid flick again. Yet his next movie will be a production of the very first script he sold, Labor of Love. I can honestly say that this is the worst script Night has ever written. It’s even worse than The Little Mermaid 2 (it’s a super-sap-fest about a man who walks across America after his wife dies).

If Night wants the adulation of movie fans and the industry – which deep down I think he does – he needs to keep playing in this sandbox. Tiny horror movies with no expectations. Small budgets that force him to get creative with his storytelling. That’s where he makes his best stuff. However, I’m afraid we’ll be cursed with M. Night Egomalan again. And just like old geezers who turn crazy after sundown, there’s not much we can do about it.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Movies are about unresolved relationships. We talk about this all the time here. In every relationship in your movie, you want to pick out something big or small that’s unresolved, then use your story to explore and resolve that issue. The Visit taught me that you can have unresolved relationships with characters who aren’t even in the movie! A big off-screen character here is the father, who brother, sister, and mom, all have issues with for leaving them. I liked how The Visit used those unresolved relationships with dad to drive a lot of the character development here. Tyler, in particular, seems very hurt by the fact that his father left, and partly blames it on himself. I also really liked the way they resolved this relationship. No, it wasn’t by calling the father and demanding answers. If you read Thursday’s “Cinematic Writing” post, you know that you want to solve all script problems by SHOWING AND NOT TELLING. We get closure when Becca, who swore she’d never use any footage of her father in her documentary, ends up including footage of him with them when they were younger. All we see are the images of him/them spliced into the final cut, but that’s all we need. We know they’ve finally found closure with the dad.

One of the things I’ve always tried to convey to you guys is that screenwriting is NOT about writing. It’s about storytelling. This can be confusing and a little frustrating and has actually caused quite a few arguments in the past. Because I don’t want to go into some long explanation of the difference between the two, I’ll give you an example of each.

Example 1:

The placid grey sky beats down on Carly, a former social outcast turned flower child. She drags her last cigarette out of a dirty box stuck between the car seats and lights it with an immediacy that belies an obsession with her addiction.

Example 2:

Carly taps the wheel of her car nervously. She checks her side-view mirror. A cop is getting out of his car. She’s been pulled over. She takes a deep breath and sucks down a cigarette. She checks the passenger seat. A newspaper lies there. She slides it forward, revealing a GUN. She checks the side-view mirror again. The cop is coming towards her. She glances at the gun again, her mind racing. Another drag of the cigarette. With the cop only a second away, she GRABS THE GUN, and hides it under her shirt.

Do you notice the difference? In the first example, or the “writing” example, there’s nothing happening other than the writer talking about the character and the setting. In the second example, there’s an actual STORY. Someone’s in trouble. They have to make a choice. There’s an element of suspense. That is STORYTELLING.

The sooner the screenwriter understands the difference between these two things (I’ve found it takes most writers 3-5 scripts to get there), and adapts the storyteller method, the sooner they start writing good scripts.

Now this doesn’t mean you’ll never take a moment to describe a scene or introduce us to a key character. Of course you’ll need to do this. But the “writer” always makes his/her words the star, as opposed to looking for ways to create mystery or build suspense. And that’s where they get into trouble.

Despite this, I realize that storytelling cannot exist without writing. You cannot convey character actions and plot without putting words on the page. And so which words you choose and how you string those words together matters. What I’d like to do today is give you a road map for showcasing your writing in a way that supports your story.

I call this CINEMATIC WRITING. Cinematic writing is writing that makes your screenplay feel like a movie. The goal here is to eliminate the “novelistic” writing approach, where you’re basically just showing off, and make your words work for your script.

Cinematic Writing comes in three flavors.

1) Show don’t tell.

2) Visual cues.

3) Supplementation.

SHOW DON’T TELL

The first one should be obvious. Yet time and time again, I see writers fail to do it. But this is one of the easiest ways to make your writing cinematic – by conveying your story in actions as opposed to dialogue. And it really kicks ass when you do it well. There’s something about an action that hits the reader harder than a line. The trick to adopting this method is to simply ask, in every instance of your script where dialogue is spoken, “Can I convey this moment visually instead?” In the opening scene of “It Follows,” for example, we see a seemingly crazy girl running from something in the middle of her suburban neighborhood, despite the fact that nothing is there. It’s a purely visual scene that sets up an intriguing mystery. I’d much rather see that than have two people discussing the act. Now, of course, sometimes dialogue is necessary (and even preferable) when writing a scene, but if you want your script to contain that cinematic flourish that convinces the reader they’re reading a MOVIE, you need a lot of showing (and less telling!).

VISUAL CUEING

Let’s say you’re writing a scene that has a couple arguing in an apartment. How do you write that scene? Chances are, you’ll describe the apartment, the characters, and then go into basic back-and-forth dialogue between them. In other words, the most UN-CINEMATIC representation of the scene you could possibly write. When you visually cue, you look for visual ways to creatively explore the scene cinematically. For example, instead of the basic “two-character-talk” scenario, maybe the scene starts on a photograph taped to a refrigerator. It’s of our couple, at a baseball game, looking as happy as any couple you’ve ever seen. In the meantime, we hear (but do not see) an argument in the background. We slowly back away from the fridge, where we see more happy photos of the couple, and continue to hear the argument in the background. We move along the floor, where we see a scared dog staring up at his screaming owners, and finally end up on the couple, as they’re ending their argument. Do you see how much more cinematic this second option is? The trick to visually cueing is to imagine you’re the director. Find interesting places to put the camera. Take note that you don’t want to write camera directions into your script. But you want to think in terms of camera placement. By doing so, you open yourself up to way more visually creative scenes.

SUPPLEMENTATION

Fancy writing on its own is useless. As I pointed out in the opening example, who the hell cares how visually Carly smokes a cigarette? To avoid this, make your fancy writing a tool to supplement the action on the page. For example, if you write three paragraphs on how beautiful the mountain our main character is climbing is, we could give two shits. HOWEVER, if that same character is in danger? If he’s stuck on a mountain ledge and his next few moves will determine whether he lives or dies? Now you can start describing the mountain around him in detail and we’ll be riveted. Why? BECAUSE NOW THE DETAILS MATTER. They directly influence the fate of our hero. This is supplementation. It’s using expressive prose to supplement important story beats. I’m reminded of one my favorite scripts of the year, February, when a character is creeping through a room because she’s heard a noise. The writer covers every little sound and movement in extreme detail. But it works. Why? Because the character is in potential danger. We get the sense that something bad is nearby. Therefore, the details pull us in. Had the writer tried to describe the room in that kind of detail BEFORE our character was in danger? It would’ve been boring-sauce.

The main idea I want to convey here is that your writing should never be the star of your screenplay. Writing is a tool that should be used to support the storytelling. I’m yet to hear a producer say, “I hated that story but man, that script was really well-written. Let’s buy it.” It just doesn’t happen. By transitioning your novelistic writing approach to a cinematic one, you’re allowing your words to work for you as opposed to against you. So get in there and start writing movies as opposed to glorified writing exercises. I promise you a more positive response from readers. Good luck!

I get questions from writers all the time on things as varied as how to make a serial killer likable to how to end writer’s block. And what I’ve found is that all of these questions are stupid, just like the people who ask them.

I’m kidding! There’s no such thing as a stupid question. Most of the time at least. One of the things I’ve been asked about a lot lately is backstory. Now backstory, as most screenwriters know, is a bad word. We’ve all read or watched that mind-numbing scene where an unprompted character decides that he just has to tell the supporting character how daddy touched him when he was 19.

Backstory is the ugly cousin of exposition, a kid who’s already ugly as it is. And since exposition is often boring, the rule of thumb is to only include it when you absolutely have to. You want to extend that rule over to backstory. It is likewise evil, and therefore to be treated like a pimple on prom night. It MUST be eliminated.

I’ve found, by and large, that the longer screenwriters write, the less backstory they include. There are very successful writers, in fact, who believe that you don’t need any backstory at all. Since a movie takes place in the present, anything in the past is irrelevant.

And someone might argue, “But how can we really get to know a character if we know nothing about their past?” And Backstory Hater would reply, “The only tool you need to reveal character is choice.”

We figure out who people are by the choices they make. This is true in real life just like it is in the movies. If you’re on a first date and an elderly woman falls down in front of you, the choice your date makes is going to tell you a lot about them. If they walk around the woman, we know they’re an asshole. If they jump into action to help her, we know they’re good.

To these veterans, the idea is to create dozens of choices (small and large) throughout the script that your main character will encounter, and to tell us who he/she is through those choices. A small choice might be if your protagonist is given the option to order salad or a one pound greasy cheeseburger. Whichever one he chooses will tell us a lot about him. Ditto if he opens the door for his date or waits for her to open it while he texts away on his phone. Ditto if he chooses to drink 8 martinis or just one.

I tend to agree with Backstory Hater on this approach. I think backstory is troublesome even in the best case scenarios. The revelation of it rarely feels natural and any time we move into the past, we’re halting the present.

So are you telling us never to use backstory, Carson? Like, ever? Can we still visit our childhood friends? Reminisce about our first kiss?

No, you can’t do those things. I forbid it. But you can use backstory in one key instance: When defining what led your main character to inherit their FATAL FLAW.

A reminder on “fatal flaws.” This is the internal “flaw” that holds your character back from being whole. Even if they succeed at obtaining their goal (“Deliver R2-D2 to the Resistance to destroy the Death Star”), they will still have failed if they haven’t overcome the flaw within themselves. Why? Because there’s still imbalance within them. They’re the same person – still unhappy. Luke Skywalker’s flaw was that he didn’t believe in himself. He finally did in the end, which is what allowed him to destroy the Death Star and be happy.

Once you know your character’s flaw, you can target the specific moment from their past (their backstory) that brought it about. So in Good Will Hunting, Will Hunting’s flaw is his inability to let others in. Now that we know that, we can ask ourselves, “What happened when he was younger that stopped him from letting people in?” Well, his father used to beat him regularly. That had some impact. So that’s potentially something we could bring up in the story (which they did).

It doesn’t do the script any good if your hero babbles on about his former life as a male stripper if stripping has nothing to do with what he’s struggling with now. It’s just noise and can actually work against you, as your reader will try to find meaning and importance in a detail that contains neither. Now if your main character’s flaw is that he’s sexually promiscuous and it’s ruining his life, then maybe that stripper backstory becomes relevant.

So to summarize, avoid backstory at all costs. Try to tell us who your character is through their choices instead. But if you must include backstory, only include the details that inform your character’s fatal flaw. Since character transformation is one of the keys to emotionally engaging your reader, information about why your character is suffering from his flaw can strengthen our understanding of that transformation.

And with that, I’ll leave you with a few other tips on how to convey backstory in your script. If you must do it, do it right!

1) Have your character be forced into telling their backstory – If your character is forced into talking about their past, we’re more focused on them being forced than we are on the artificiality of a character discussing their backstory. If your character is being tortured, for example, and asked about his past, we’re not thinking, “Oh, backstory moment!” We’re hoping the poor guy lives.

2) Always keep backstory as short as possible – Just like exposition. Try to disseminate backstory in bite-sized nuggets. Instead of Indiana Jones going on a one-page monologue about the time he was almost killed by a snake, we see him react to a snake in the plane and scream, “I hate snakes.” That’s it!

3) Backstory-as-mystery is often more powerful than literal-backstory – You don’t have to tell us everything. You can hint at things. And this is actually more powerful because it forces the audience to fill in the gaps themselves. Remember in Alien when we saw that giant stone structure of an alien manning some kind of gun/telescope? Our minds were racing trying to figure that out. How boring would that have been if one of the characters knew what it was and explained it in detail to us?

4) Show your backstory. Don’t tell your backstory – The old show-don’t-tell movie rule is multiplied ten-fold when it comes to backstory. It’s always more powerful if you show us. In Bridesmaids, our two main characters walk past our heroine’s failed cupcake shop. There was tons of backstory in that one image.

5) Have others bring up backstory, not your hero – The less your hero is talking about their own backstory, the better. Always think of a way where someone else brings it up. This is why the “resume” scene works so well in movies. It’s an easy way for the interviewer to read off your hero’s backstory without the viewer getting suspicious.

6) Some genres are more accepting of backstory than others – Backstory doesn’t work well inside the faster-moving genres like Thriller and Action. But in a slower drama, it’s expected that some backstory will be offered.

7) A good place to include backstory is the first scene – The biggest problem with backstory is that it INTERRUPTS the present story. Therefore, if you give us a flashback before your present-day story’s begun, you’re not interrupting anything. This is why you see so many movies start with flashbacks and then cut to: “15 years later.” If you’re going to do this however, cover ALL of your backstory in that single scene. Don’t keep giving it to us 70 minutes later.

8) If you can find a way to make backstory entertaining, you now have super powers and all bets are off – This is what the pros do. They’ve figured out all the tricks to hide backstory inside of entertainment. And if you can do that, none of these rules matter because you’ve learned to make backstory just as entertaining as present story. Look at the scene where Clarice goes down to talk to Hannibal Lecter for the first time in “Silence of the Lambs.” Remember the moment when they show Clarice a picture of one of Hannibal’s victims? That’s a writer giving us Hannibal Lecter’s backstory. But we’re so focused on the anticipation of seeing this monster that we never consider for a moment that the writer is doing this. Master this technique and you will be unstoppable!

Genre: Biopic

Premise: Chronicles the early life of L. Frank Baum, the author of “The Wizard of Oz.”

About: Unknown scribe Josh Golden hit the kind of jackpot that can turn a black and white world into a color one. He was a finalist in the Nicholl Screenplay Competition (with this script), then sold it to New Line. He’s even got mega-producer Beau Flynn (San Andreas, Rampage, Requiem for a Dream) producing the movie. The script hit the trifecta when it landed on last year’s Black List, grabbing up 11 votes. Things could not be more yellow brick golden for Josh Golden.

Writer: Josh Golden

Details: 113 pages

I had to give up on a few Black List scripts before I got to this one. I don’t know what’s going on with the current state of specs but, sheesh, I’m struggling to find good material in this jungle.

It started with Tau, which was torture porn. I don’t know if movies about sexually torturing women are going to work in this day and age. The feminist movement has pretty much put the kibosh on that. Not to mention, the genre feels dated, like something you’d find on an abandoned Eli Roth hard drive.

From there I went to Professor Psghetti, about a children’s show host who hates children. This one barely crept onto the Black List. I love the irony of the premise but there are 5-6 of these scripts out there already. This is why it’s a good idea to track the industry. While an idea may not be well-known to the masses, it might be very well-known to all the agents in town.

Then I read Erin’s Voice, about a deaf man who discovers that he can hear his local barista (and only her). I went into this one thinking it was a comedy all the way, but everything was being played straight. I admired that for awhile – that it was different – until I hit Act 2 and realized I had no idea what kind of movie the writer was going for. A straight-forward drama about a guy who can magically hear his barista? Know your genre. Know what kind of movie you’re writing. Calgon, take me away.

That led me to “Oz.” I figured how bad could a biopic about the guy who created “The Wizard of Oz” be? Let’s find out!

The unfortunately named Lyman Frank Baum is a writer. But unlike today, in 1898, writing didn’t exactly pay the bills (that’s sarcasm if you couldn’t tell). His wife, Maud, is bummed that Frank’s giving up on writing so easily, but she’s pumped to start a family, so bye-bye dreams.

This sends Frank and Maud off to the booming town of Aberdeen, South Dakota, where Frank hopes to open a party store and take advantage of the new money in town. While working at the store, Frank helps tend to his niece, Dorothy, a beautiful young girl who’s beset by a crippling illness.

Because Dorothy isn’t healthy enough to go outside, Frank brings the outside to her, entertaining her with imaginative tales of far-off worlds where anything is possible. When Maud overhears Frank tell these amazing stories, she reminds him just how talented he is.

If he could, say, turn all of those stories into a book, he could entertain millions. But Frank doesn’t believe he’s got it, and when the shop fails, he becomes a travelling salesman, visiting the entire Midwest, selling fine China.

It isn’t until Dorothy’s health goes into a tailspin that Frank finally gives his book a shot. Using her as inspiration, he creates one of the most imaginative pieces of fiction of all time, The Wizard of Oz.

So there’s a cynical side of me that looks at this and says… haven’t we seen this before?

In Saving Mr. Banks? In Seuss? In The Muppet Man? In Finding Neverland?

Haven’t we been down this yellow brick road already?

Before I can get too upset about it, I must remind myself that the Author-Biopic is an official genre now. It’s not something where they made two of them and the world moved on. These are films that writers are going to keep writing.

Once you accept that, Road to Oz, like a well-toasted munchkin, is a little easier to digest. But may I offer an observation amidst this realization?

Once something becomes a “thing,” executing the most straight-forward version of that “thing” is no longer an option.

There was a time, long ago, where the only way you could get cheese was from a block. If you were in the cheese business, you were providing it in block form. So let’s say you wanted to break into the cheese business at that time. What do you think your chances would’ve been had you delivered your cheese in a block, JUST LIKE EVERYONE ELSE?

Maybe if your cheese was the greatest cheese in the land, you would’ve succeeded. But chances are it wouldn’t have been. In which case, your business would’ve died a miserable cheesy death.

However, what if you came up with the idea to SLICE the cheese? To offer it up in SLICES form? You would’ve found a new angle into the cheese market. Or maybe you lived in Wisconsin and thought to yourself, “Boy, cheese would be so much better in ball form.” So you created cheese balls. Again, you were FINDING A NEW ANGLE into this market.

It’s the same thing with movie genres. Even sub-genres. Everyone is delivering a cheese block. You need to give them cheese sticks. “Road to Oz” isn’t a bad script. But the execution is the exact same execution that all the author-biopics are using. Wikipedia timeline. Brief flashes into imaginative dream sequences. Clever nods to the writer’s most famous creations. The End.

And that’s hard to digest because The Wizard of Oz was one of the most imaginative pieces of fiction ever written. It became what it is because Baum took major chances. We don’t see that kind of bravery here. And I don’t know if a screenplay about Baum’s life should be held to that expectation or not, but we should at least see some imagination, right?

And it’s the obsession with incorporating these clever nods to the writer’s creations that really hurts these scripts (for example – a group of monkeys all of a sudden become FLYING MONKEYS in Frank’s imagination).

Because that’s not what these scripts should be about. They need to be about a PROBLEM that’s keeping the protagonist from achieving his life goal. Look at the script, Dalton Trumbo, which I reviewed a few weeks back. In that script, the PROBLEM is Trumbo getting blacklisted. There’s the obstacle that our hero must overcome.

I’m not sure what the problem is in this screenplay. I suppose it’s that Frank doesn’t believe in himself enough to write his book? But that was never infused into the story in any meaningful way. We’d just occasionally hear somebody – usually Frank’s wife – say, “You’re so talented. You should be writing your book.”

For a story to work, the problem must BLOCK THE CHARACTER from success. And it must be clearly identified so that we, the audience, know what our hero is fighting against, what he must overcome. If we don’t know what a character must overcome, how can we invest ourselves in their story? We’re not even sure what they’re trying to do!

One of my favorite screenplays of the year was another biopic, Joy. Joy’s PROBLEM was clear. It was this mop she invented. She couldn’t figure it out. No one would buy it. It became her obsession. So we wanted to see her conquer that mop. That was the PROBLEM that propelled our hero and our story.

Why didn’t we have that here?

I mean hell, The Wizard of Oz had one of the clearest problems of any movie ever. Dorothy needed to get back home. Why not use that as inspiration for “Road to Oz?” Frank was a travelling salesman. Why not go full-Kaufman and have him get lost in some far-off land from which he needs to find his way home? The Tim Burton version of the story. At least then it would feel unique.

I should finish this up by reminding everyone I’m not exactly in tune with why people see biopics. I think folks just want to see how someone got their inspiration, particularly if it takes them to another world (like 1898). And I should respect that it doesn’t have to be more complicated than that.

But the storytelling purist in me wants conflict. It wants problems that the main character must overcome. And the problems in Frank’s life – at least this version of his life – feel too lightweight. For that reason, I couldn’t get over this rainbow.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t think that because you’re not writing Die Hard, you don’t need a PROBLEM for your main character to overcome. You need PROBLEMS in character-driven movies just like you need them in high-concept movies. I’d argue that the problem is the movie. If you don’t have that clear DOMINANT OBSTACLE in the way, it’s difficult for your story to gain traction, since we’re never clear what it is our main character is trying to do. Again, in Dalton Trumbo, another writer-biopic, the problem is clear: He’s been blacklisted. That gives the movie form, it gives it clarity. It allows us to participate and understand what our main character must defeat.

What I learned 2: Never rest your author-biopic on gimmicky nods to the writer’s famous creations. In other words, if you’re writing a biopic about Steven Spielberg, don’t think that you can dress him up as a T-Rex for Halloween, give him a dog named “Jaws,” have a giant boulder nearly crush him at summer camp, and have his family see a flying saucer at Thanksgiving dinner, and call it a day. Those clever nods should be the icing on your story. They should never be the cake. The cake should be the PROBLEM that your protagonist must overcome (see above).