Search Results for: F word

Genre: TV Pilot – 1 hr. Drama/Comedy

Premise: A look at the behind-the-scenes drama that occurs on a “Bachelor” like reality show.

About: Had you told me a month ago I’d be reviewing a Lifetime teleplay about reality television, I would’ve told you to bring me your torch. You’ve been voted off the island. But Lifetime is really high on this show and is giving it the full rollout treatment in anticipation of its June 1st premiere. Also, half-a-dozen people have e-mailed me on separate occasions to tell me how much they liked the script. And that doesn’t happen at all with TV pilots. The show was created by Marti Noxon, who adapted the YA novel, “I Am Number Four,” as well as the updated “Fright Night.” Marti’s also written a ton of TV, with her resume including Mad Men, Grey’s Anatomy, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, and Glee. Co-creator Sarah Shapiro, is making her writing debut here.

Writer: Marti Noxon & Sarah Gertrude Shapiro

Details: 55 pages – 8/28/13 draft

I’m guessing the percentage of the Scriptshadow reader base that also watches reality television is equivalent to the percentage of Mormons who caught 50 Shades of Grey. You’re not alone. The industry has never liked reality television.

It’s the reason why nobody would even glance at a screenplay that dealt with reality shows. The unofficial official company line was: Never write a screenplay about reality TV.

But that’s the funky thing about Hollywood. Is that something’s a given until all of a sudden it isn’t. And the “isn’t” is, in most cases, a good script. If you write a good script, your friendly neighborhood rule book can be tossed out the window.

So I have an extra modicum of respect for anyone who breaks through the firmly locked gates of Hollywood’s ivory tower with something different. Typically, when Hollywood wants to keep someone out, they succeed.

29 year-old Rachel is a reality show producer. Reality show producers are the behind-the-scenes workers who prime the contestants on your favorite reality show that you tell everyone you don’t watch to say what the show wants them to say. The ones who say they think they’re “falling in love” with Douglas the Bachelor even though they just met him 20 minutes ago? Yeah, Rachel’s the one who makes sure that soundbite happens.

A producer is SUPPOSED to stay objective and let the talent dictate the course of the story. But come on. If that were the case, you wouldn’t get those level 17 meltdowns from the former prom queen who’s just realized that no man will ever consider her marriage material. It’s Rachel who plants that seed a few days earlier so that when the contestant’s voted off, it all comes spilling out in her exit interview.

The thing is, Rachel hates her job. She considers it to be more soul-sucking than doing porn and if there’s anywhere else she could be, even if it was cleaning sewers in Mumbai, she would do it. That is, if she wasn’t so damn good at her job. Rachel can convince anyone to do anything, a highly valued skill in the world of producing reality television.

In this first episode, those skills will be put to the test when our “Bachelor,” Adam Conway of Conway Hotels, decides to quit just minutes before the show’s to begin. Rachel uses some Darth Vader level Jedi mind tricks on Adam to get him to reconsider. But they end up backfiring. Adam agrees to come back but only if he gets to have Rachel around all the time.

Of course, that leads to the most obvious of questions. If Adam and Rachel are going to be around each other so much, what’s going to happen between them? And if something’s going to happen between them, what does that mean for the 18 women vying for Adam’s hand in marriage?

As demand for product keeps expanding in television, more and more of these blacklisted ideas (“Never write about reality TV!”) are going to get lifted. TV is in this really rare place in history where the demand for product is way bigger than the supply.

So if you’ve tossed an idea out just because you’ve heard Hollywood hates it, it might be time to dust that idea off and write it. Today’s show proves it’s possible.

But it wasn’t just the idea that got the pilot on the air. This is good writing. In fact, Unreal utilizes one of the most powerful tools available to writers to make it work. IRONY.

The Bachelor is the personification of a fairy tale. Every date is postcard perfect. Every conversation is filled with laughter. Every kiss is framed against a golden sunset. So what is Unreal about? It’s about the cheating that goes on behind those dates. It’s about the manipulation used to guide those conversations. It’s about the bullying that must be used to get that golden kiss. Unreal is about the slimy underbelly of reality television, and that’s what makes it so fun.

“Irony” is a tough word for some screenwriters to grasp. So let’s put it this way. One of your biggest weapons as a writer is CONTRAST. Whatever extreme you have in one aspect of your idea, try to contrast it with the opposite extreme in another.

So if you have a show about happiness, contrast it with a crew who hates their jobs more than anything. If your main character is a serial killing cannibal, contrast that by making him polite and inviting. If you’re writing a scene about a woman dumping her boyfriend, create contrast by setting it at his birthday party. Contrast, my fellow screenwriting enthusiasts, is a really easy way to look like a really good writer.

Also, when you’re writing a romance-based show (or a show where people hook up a lot), you want to make it as hard for those people to hook up as possible. The more difficult it is for people to hook up, the more drama you’re going to get. So you have this show here where contestants hooking up with crew can destroy the entire production. So there are real stakes to people getting together who shouldn’t be together.

The only thing wrong with this pilot is that the execution’s vanilla. Everything kind of went the way you expected it to, save for a Rachel breakdown in the final act. You can even sniff out where the main hook-ups of the season are going to be. That can be enjoyable to an extent. Waiting for two people we’re dying to see get together finally get together. But there still needs to be an element of surprise to a show. And Unreal hasn’t shown me it’s capable of doing that yet.

I will say, though, that if you want a dark humorous look at the behind-the-scenes shenanigans of a reality television show, Unreal does a pretty good job of delivering.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Make it so your character must consistently go against their moral compass in order to push the story forward. Rachel hates manipulating these contestants. But she has to in order to get the big moment for the cameras. For example, when one of the girls is ready to give up, Rachel uses her knowledge of the girl’s previous boyfriend physically abusing her to promote Adam as the opposite of him. This dirty trick reenergizes the contestant and now she’s back pining for Adaman’s attention. Maybe a better way to convey this is this: Have your main character sell a little piece of their soul every time they have to do something important. This will ensure that your character is always fighting an inner battle, which audiences love to watch.

With indie sleeper “Ex Machina” kicking ass this weekend at the box office, I thought those who missed my script review might want to check it out. Enjoy! And now on to Black Mass…

Genre: Drama/Biopic

Premise: The real-life story of Whitey Bulger, a notorious Boston gangster who became an informant for the FBI to help take down the mafia.

About: If you’re a screenwriter and you haven’t explored writing a biopic, what’s wrong with you?? The genre is taking over the industry. And I think I know why. With the “star system” in Hollywood declining, biopics have become the one remaining area for movie stars to shine. Nobody goes to American Sniper if Ted Danson is playing Chris Kyle. Black Mass stars Johnny Depp and was to be directed by journeyman filmmaker Barry Levinson, but they decided to go with hot new shiny object Scott Cooper instead, who directed the gritty Christian Bale flick, “Out of the Furnace,” and the Jeff Bridges country music feast, “Crazy Heart.” Final screenplay credit was split between Mark Mallouk, who’s making his screenwriting debut here (he was previously a producer) and Jez Butterworth, who’s credited for such films as Edge of Tomorrow and Get on Up. Interestingly enough, this script notes that Johnny Depp has final say over the screenplay. I suppose this is more common than we know but it was a little surprising to see it in writing.

Writer: Mark Mallouk (this draft doesn’t yet include Butterworth) – based on the book “Black Mass: Whitey Bulger, The FBI and a Devil’s Deal” by Dick Lehr and Gerard O’Neil

Details: 115 pages – undated (looks to be a late 2012 draft)

After the recent trailer for Black Mass hit, I had to read the script. I love that they did something different with the trailer, focusing on a single scene instead of a bunch of them. And Johnny Depp. Whoa! The guy is practically unrecognizable as Whitey Bulger. And he’s acting again! I’m not sure you can say that about his previous five movies. Johnny Depp is the most kind, gentle, soft-spoken person in real life. But that man in the trailer? That was someone entirely different. That man was terrifying.

It’s 1974 and FBI Agent John Connolly has just moved back to Boston as the self-proclaimed “savior” of the city. The Irish and Italian gangs have turned the town into a hell-hole and he’s going to be the one to clean it up. His fellow Feds are skeptical, but Connolly’s got a secret weapon. He knows Whitey Bulger, the man running the Irish gangs.

Connolly’s idea is this. The FBI really wants the Mafia (the Italians). He recognizes that getting them out of the way is good for the Irish. So why not use the Irish’s knowledge about the Italians – the kind of information the Feds don’t have access to – to take them down? So Connolly goes to Bulger and asks him if he wants to be an informant.

It takes some convincing on both sides but soon everyone’s in, and thus begins a working relationship between Connolly and Bulger. Bulger feeds Connolly info and the FBI looks the other way when Bulger does unsavory deeds.

The problem is, Whitey Bulger works on his own time frame, not the FBI’s. He wants to know he can trust Connolly before he just starts throwing information at him. So there’s this constant tug-of-war between Connolly and his bosses regarding time. He needs more. They give him less.

Eventually the plan starts paying off, with Bulger giving the FBI the mafia’s hideout. But it’s a double-edged sword. With each new thing they learn about the mafia comes a new tidbit about Bulger himself, who they’re learning is a MUCH bigger criminal than anyone knew. And thus the question is asked. Are they getting rid of a demon only to replace him with the Devil?

Black Mass starts out with a great opening sequence. It’s 2011 and one of the FBI’s ten most wanted men, Whitey Bulger, has been spotted living in a small apartment in Santa Monica. The man who’s reported him to the Feds, the apartment manager, is tasked with tricking the notorious gangster to come outside his apartment so the FBI can scoop him up and arrest him.

Whitey is a man who used to have people like this manager sawed into pieces for even considering such a thing. But when the Feds tell you you have to do something, you do it. The scene is not only packed with suspense, but it brilliantly sets up our subject, conveying just how much of a badass Whitey Bulger is.

At the end of this scene, I scooched into my chair with a smile, ready for a long exciting adventure about the man who many feel was the most violent and dangerous in Boston’s history. You can color me disappointed, then, when that adventure never came.

Black Mass makes a shocking choice early on that ends up neutralizing its biggest asset. Instead of telling us the story through the eyes of the legendary Bulger, Black Mass focuses on the vanilla Jack Connolly to tell its tale.

This may have worked had we seen enough of Bulger’s antics to satisfy our morbid curiosity. But the script adds this storyline by which Connolly thinks Bulger is a harmless second-rate criminal. That’s how he was able to sell to the Feds going after the Mafia and not Bulger himself.

For that to work though, Connolly (and by association, us) can’t see Bulger do anything bad. As you’d suspect, this has a catastrophic effect on the level of drama in the film. Since Bulger can’t do anything bad, Bulger can’t do… well, anything at all! All of Bulger’s scenes are relegated to him nodding and doing whatever Connolly asks of him. I hate to put it this way, but 80% of this movie is Whitey Bulger being the FBI’s bitch.

I was shocked. Where was this terrifying legendary criminal I’d heard about? He wasn’t in this film. Which means Black Mass runs the risk of being the single biggest example of false advertising in biopic history. It would be like making a movie about Michael Jordan and never showing him play basketball.

As for that great scene in the trailer – it’s in this draft. But it’s an outlier. We don’t get any other scenes like it (save for 1-2 generic kill scenes) to show how terrifying Bulger is.

The plotting had issues as well. There’s a distinct lack of BUILD as the story goes on, and I think that’s because the script failed to establish the stakes of getting rid of the Mafia. I barely knew anyone in the Mafia here and it was never conveyed to me why getting rid of them was so important.

Lots of writers mistakenly believe that just saying so is enough. So if a character says, “Man, that Mafia is bad. They killed that woman last week,” then we’ll want the Mafia taken down. But that’s not how movies work. Movies work by SHOWING. Not TELLING. If you show the Mafia rip an innocent man to shreds because he looked at them the wrong way, NOW we’ll understand why the FBI needs to stop them. We’ve seen how dangerous they are with our own eyes.

But that’s a small part of a much bigger problem. Nobody really does anything bad in this movie. Not Whitey. Not the Mafia. It’s the PG version of the Boston crime story. Sure we hear about some bad things, but I don’t go to a movie to hear about something. I go to SEE it.

Of course, the nature of development is that you keep working on a script until it’s the best that it can be. And they did bring on another writer to do some drafts after this one. But something tells me the current approach of this script is unfixable. You can’t neuter and borify the most ruthless killer in Boston history. You have to let a character like that loose.

I went into this script thinking Whitey Bulger was a major badass. I left thinking he was just a regular guy who occasionally committed crimes.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Use visual cues to convey time passing. There was a moment in Black Mass where the FBI director tells Connolly, “It’s been six months and Bulger hasn’t given us anything!” So poorly was the passage of time conveyed, that had that same character said it had been “2 weeks,” I wouldn’t have batted an eye. Improperly conveying time can make a script feel drifty and sloppy. So use visual cues to help the reader along. For example, you might make a key female character pregnant. A tiny bump one scene and a big bump another scene instantly conveys 6-7 months have passed. A family gets a puppy. A few scenes down the line, that dog is now full grown. Highlight seasons changing. It’s sunny and 85 out. Cut to next scene, it’s now snowing. These are the most obvious examples so I actually encourage you to be creative and come up with your own. But if we have no idea how much time is passing in your story, we can become confused. And confusion often leads to frustration.

What I learned Two: If you have a compelling character, you want to construct a storyline that allows that character to thrive. For example, if you’re writing a story about the greatest astronaut in history, you probably don’t want to set the entire movie down on earth.

While everyone clamors to perfect their Scriptshadow 250 entries, a bold group of screenwriting gummy bears choose to place their letter spaghetti in front of the interconnected computer sphere in hopes of rainbow transformation. May we wish them a transition to a higher state of being.

Title: To Boldly Go

Genre: Biopic

Logline: In 1964, writer Gene Roddenberry struggles to get his vision on television – a show called “Star Trek”.

Why you should read: Three reasons. One – unlike other biopics which give you the whole Wikipedia routine, my script focuses on a year-long period in a man’s life, during which he has a clear goal. Two, it could generate a discussion on the act of using licensed properties you do not own in a spec written as a sample. (Like “Wonka”, which I am certain will not be made unless Roald Dahl’s zombie corpse approaches a production office, gobstopper in hand, and signs off on it while offering casting notes: “Two words: Get Gosling.”). And, three, my script comes from the heart. My father passed on in ’91, when I was kid, and one of the things he instilled in me was a love of science fiction, particularly “Star Trek”.

Title: The Camelot Club

Genre: Comedy

Logline: A religious man and his sexually deviant cousin unexpectedly inherit a run down strip club and have two weeks to make fifty thousand dollars or be killed by a seven foot transsexual pimp.

Why You Should Read: What do you get when you add together a 6’3” ginger Pole and an average height, golden tan Croatian? The Camelot Club, a combination of tanned, god-like overconfidence and the inherit self-loathing that comes with being orange and pale. We came together to write this script so we could split the crushing despair that comes when someone inevitably tells you your scripts reads like German is your native tongue (an actual criticism I received on my very first script, which hurt even more considering the only language I know is English). In the end we are just a couple of struggling artists looking to be accepted into the soft, voluptuous bosom of the screenwriting community (an agent and management would be nice, too). After learning the English language more better, and getting the screenwriting turds out of our systems, we put our minds together and produced The Camelot Club. And now I would like to end on a testimonial from my bi-polar, alcoholic brother, “…this script was so good it made me wish I was tri-polar…”. Enjoy!

Title: The Stone Addendum

Genre: Action

Logline: An Israeli secret agent has less than two days to prevent a terrorist hostage exchange in the U.S., but he must rely on help from an innocent Muslim woman that he’s ordered to kill once the mission is complete.

Why you should read: This script appeared in AOW a ways back to pleasant but uneventful reviews. Since then, with the help of Carson’s notes, it’s gone through a major makeover, and registered a Page Quarterfinals, a BlueCat Top 5%, and most recently a Top 25 in the Tracking Board. The latter billed it as TAKEN meets THE HURT LOCKER, and “the perfect blend of brains and brawn.” I think I’m in the red zone on this one, but can’t seem to punch it into the end zone with producers. Feedback from the SS community would be more than helpful. Thanks in advance to anyone taking a look.

Title: Tammy

Genre: Comedy

Logline: A young man from a strict religious family awakens from a severe head injury with the personality of a vulgar, slutty party girl named Tammy.

Why you should read: (from Tammy) heyyyy. so like, i didnt write this er whatever. the movie. but its awesome. mainly cuz its about me. myy names Tammy… & yes, im way hotter then that slam pig melissa mccarthy who took my name and shat on it. i like to party & get schwasty, unlike my dumpy foster mom. but seriously. u hafta read this. normaly, id suck u off, but i cant do that thru email… so quit beatin ur ham & open this script. u wont be sorry & if u r… gimme ur address & ill make it up to u. im like UPS… i deliver my box to strangers ;)

Title: Tampa Bay

Genre: Buddy Action

Logline: An old, homophobic, U.S. Marshal must seek the assistance of a gay FBI agent to solve the murder of a neighbor’s daughter.

Why You Should Read: I think it’s about time we had an action hero who just happens to be gay. He should be a badass first, and gay second. So that’s exactly what I wrote.

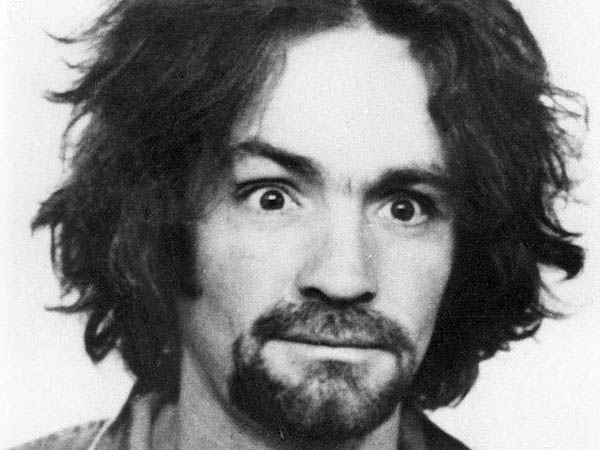

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama/Procedural

Premise: A veteran cop teams up with an unconventional young partner to take down Charles Manson in the days before Manson’s infamous killings.

About: Aquarius has been steadily gaining buzz ahead of its premiere next month. The gritty team-up of two cops in search of Charles Manson seems to have been at least, in part, inspired by True Detective. If not in this draft (which is dated 2013), then in its subsequent rush to get to the small screen. Writer John McNamara is a bit of a journeyman, writing for 15 different TV shows dating back to 1983. He’s arguably experiencing the biggest moment of his career, not only writing this, but also the feature, “Trumbo,” starring Bryan Cranston, which chronicles the life of screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, who was one of the screenwriters blacklisted during the red scare. Trumbo will be his first feature credit. Oh, and the series will star X-Files alum, David Duchovny (playing the lead cop, not Manson, although I’d be way more interested in this if he played Manson. Now that would be funny).

Writer: John McNamara

Details: 55 pages (Revised Draft – October 28, 2013)

“What are you talking about? I’m not crazy, man!”

“What are you talking about? I’m not crazy, man!”

I’m going to try and say this politely. This was one of the most visually unpleasant scripts I’ve read in awhile. When you look at a good page of writing, it’s like walking into a clean apartment. Everything is where it’s supposed to be. The person living there cares about the placement of the chairs, the tables, the television, everything. You feel comfortable and safe.

Walking into Aquarius felt like walking into your derelict drug-dealing friend’s basement. There’s a 3 foot tall stack of dishes in the sink. A trail of ants on the wall. Garbage bags lean against objects, their shape molded into them because they’ve been there so long.

Simple things like paragraphs. You want to have uniformity to your paragraphs. 2 lines here. 3 lines there. Aquarius would rock us with a 6 liner, then hit us with a 1 liner, then a 2, then another 6. It was an assault. It was all so jagged and crude.

We also had WAY too many characters, even for a TV show. I’m fine with lots of characters if they have a place in the show. But there were like 80 cops introduced, 70 of which surely won’t be around for episode 2. And it took me until page 30 before I knew who our protagonists were.

There were also little things that made reading unnecessarily difficult. Tons of needlessly CAPITALIZED WORDS. Underlined words. Three line parentheticals!!! And that was standard. It was like this was written during a 3 day Vegas bender.

After weeding through all that mess, I was able to discover somewhat of a story. Aquarius follows LAPD Sargent Sam Hodiak. Hodiak’s called in by Grace Karn, a woman he used to date, whose 16 year old daughter, Ella, is missing. Because Ella’s father has political aspirations, they can’t make this public. So they were wondering if Hodiak could, you know, find Ella on the down-low.

Since Ella was last seen partying, Hodiak calls on Brian Shafe, a young cop who’s recently infiltrated the hippy drug scene. Shafe becomes an undercover secret weapon who works his way into the parties where he finds out a certain somebody is hoarding up all the hot girls, promising them a life of love and happiness. That somebody is a young drifter named Charles Manson.

While Manson’s interest in Ella appears random at first, it turns out there’s more than meets the eye. Ella’s lawyer father used to represent Manson. And when he stopped returning Manson’s calls, Manson took it personally. Therefore, his seduction and defloweration of Ella was payback. He lets her father know that if he doesn’t start cooperating, this is just the beginning.

Abercrombie & Fitch ad or a scene from Aquarius? You decide!

Abercrombie & Fitch ad or a scene from Aquarius? You decide!

Aquarius feels like Ryan Gosling may have consulted on it. It takes forever to get started, with a never-ending line of character introductions before any real story begins. I mean if you don’t know who the main character in a pilot is before page 30, the captain needs to be notified that the plane is going down.

This meant the last 26 pages contained all the good stuff. And there are a couple of nice scenes. Like when Shafe takes a fresh-out-of-training undercover female cop to convince Manson’s right-hand man to take them to Manson. The henchman tells them sure, but the price of admission is that he gets to bang the girl. Shafe did not prepare the female cop for this and they can’t blow their cover so he goes along with it, leading to the only scene in the pilot that contained some actual suspense.

My biggest issue with Aquarius is that if you take out the Manson element, there’s nothing left. I understand that the dramatic irony of Manson’s involvement drives the story. But that doesn’t mean you can just phone everything else in. Without Manson, these are just a couple of cops looking for a guy who kind-of kidnapped a girl (but not really, since she wanted to go with him). Not exactly a high-stakes scenario. It’s hinted at that Manson killed a girl a few months earlier. Why not start there? Now you’ve got a show.

I’m also worried about the show’s arc. We all know where it’s headed. And it’s not good. The good guys lose. So why are we watching again? Resting on the celebrity of Manson isn’t enough. Then again, maybe this is another True Detective scenario where I just don’t get it. That’d be nice. I don’t want the show to be bad. But going off this pilot script alone, it doesn’t look good.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It’s hard to make the reader care when he’s way ahead of the investigation. We all know that Manson took Ella. We saw it. The next 40 pages, then, are waiting for Hodiak and Shafe to catch up to us. You can add suspense to this scenario IF the victim is in imminent danger (Silence of the Lambs). But Ella never seems to be in danger at all. She’s a little unsure of being here. But that’s it. Not exactly a ticking time bomb scenario.

After yesterday’s spectacular surprise, the buzz is high for this week’s Amateur Offerings. If you’re too shy to display your script to the world, maybe doing the Scriptshadow 250 dance is a better option. You know how it works. Read til you’re bored. Share your thoughts in the comments!

Title: Guilt

Genre: Dark Comedy (99 pgs)

Logline: A crack-smoking lawyer, witness to a murder, tries to redeem himself by vindicating the teen prostitute wrongly accused of the crime.

Why you should read: Though I’d love to come up with some touching, true-life moment that makes this story personal, I cannot. I simply wasn’t born into the same dire circumstances as those typically faced with the horrors of an unjust justice system. I’m also not a self-absorbed coke fiend like my protagonist. But while this story isn’t a reflection of my life, I know it is for many others, and I hope I was able to capture at least some of that strife, in addition to bringing some moments of ironic hilarity.

I’ve been a long time reader of Scriptshadow, mainly because no matter what the article or review, you seem to provide something fresh every time. You could throw a rock in any direction and hit five blogs on “how to write a screenplay”, or “the 10 mistakes young writers make”, but every one of them seems to just regurgitate the same points. It’s like no one has an original perspective on the business, except you and maybe a handful of others. And to your perspective, I made this script as lean as possible, while creating a fun character that any A-list actor should be dying to play.

My initial goal in writing Guilt was to meld the tragic angst of the Verdict, with the drug-fueled narcissism of The Wolf of Wall Street, along with a healthy GSU, because this young girl doesn’t have long before she’s put away for life.

Here’s what one Blacklist reader had to say: “What makes this script so interesting is how intelligently it tackles the unjust practice of forcing innocents into accepting plea deals. It’s rare to see a comedy that can highlight such a serious social ill while still keeping the laugh factor high, but thankfully, this script does just that. Reginald is a well-developed anti-hero; his heart is usually in the right place, but his actions don’t’ always reflect his good intentions. Though not perfect (see below), his relationship with his daughter Becca is what ultimately grounds Reginald as it gives him the greatest high of all time, one he could never receive from a drug. The dialogue, in particular Reginald’s monologues, is also extremely funny and well-written.”

I hope you find it a fun read!

Who doesn’t believe in second chances!?

Title: The Creation of Adam

Genre: Thriller/Horror

Logline: When Adam, a troubled teenager, learns from his father that they both carry an evil that is passed from father to son, Adam must decide to fight the demon…or become one.

Why you should read: Last year, when my script was featured on AOW, I got a very enthusiastic email from an actor-director who wanted to make the film with his friend, a famous actress, and a couple of other talents from CAA. My screenwriter’s dream was crushed when the actress decided that it wasn’t for her.The director probably went to look for another project to do with her and I was back to writing something new.

Here it is, a thriller/horror script, Shining meets The Omen, a movie I feel so passionate about, I’m willing to cheat the lottery, direct-produce-edit it myself if I need to. So, why should you read it? Because this script has mystery, thrills, horror, very cinematic set pieces you’ve never seen before and a weird father-son relationship gone horribly bad. A reader wrote “This script takes coming of age to a whole new level” Hope you agree.

Title: Drawing Dead

Genre: Crime

Logline: An opportunistic and ambitious sniper-turned-hitman gets the opportunity of a lifetime to fulfil his ambitions when he gets the job of killing the woman he’s falling in love with.

Why you should read: I work in an advertising agency, where I’m a strategist. My best work to date by far has been the strategies I’ve developed for how to appear hard at work in an open-plan office where my screen is on public display. And so, in emails to myself, word documents and in the notes section of powerpoint slides, this script slowly came together. When people were getting too close I’d switch to my native Norwegian, just in case.

Anyways, the script is a blend of three crime sub-genres (all with a twist): the hitman movie (Gen-Y has entered the workforce), the film-noir (the femme fatale and private detective join forces) and the Mafia film (a dysfunctional crime family replaces scare tactics with modern marketing principles).

I can but hope that the whole proves greater than the sum of its parts and that the result is a fresh and interesting read. I hope you enjoy it and I very much look forward to your feedback!

Title: Cielo Drive

Genre: Action

Logline: Taken set against the Manson Family murders. Sharon Tate’s father, an Army Intelligence vet, takes matters into his own hands when he infiltrates the L.A. underground scene in order to find her killer. — Tate’s father do go undercover but it’s never been revealed what he actually found. He was close enough to finding something that the LAPD were nervous about his presence.

Why you should read: My name is Erik Stiller, and I’ve just been promoted to Staff Writer for the upcoming season of CBS’ CRIMINAL MINDS. If you like LA history and revenge-action with a good man doing brutal shit then check out this feature.

Title: THE FUSE IS BURNING…

Genre: Mystery/Thriller

Logline : A troubled man tries to find solace by searching a desert canyon for dinosaur fossils. But everything changes when a young girl is found murdered in the same remote region.

Why you should read: There’s nothing like a good story. And this one begins one hundred sixty five million years ago.