Search Results for: F word

The market is changing. Because this is America, a company isn’t doing well unless it’s growing. Stock prices must continue to rise. Dividends must continue to… … divvy. And that’s putting pressure on Hollywood to deliver product with more upside. Obviously, there’s only so much a single film can do. Only so many toys it can produce. Only so many tie-ins it can manufacture.

For awhile, the studios had a solution for this. They called them “sequels.” Clever idea, right? Sequels allowed a studio to keep making money off the same property. But sequels can take 2-3 years to make. Growth, once again, was stagnated by a seemingly insurmountable obstacle.

Enter the “universe” phase. Universes not only allow you that original movie plus its sequels. But now you can have SPINOFF films. Have a super-hero or secondary character everybody loved? Give him his own movie! Conceivably, you can now release a movie from your franchise EVERY SINGLE YEAR. Marvel proved this was a viable business model with their Avengers franchise. Pretty soon, Star Wars jumped on the bandwagon, then Universal with their horror characters, and DC/WB with the Justice League, though they seemed a little confused by the whole notion (“Universe? Ohhhh-kaaayyy. Yeah, we’ll do that.”).

Now whether this model will work for an extended period of time is another question. The reason they didn’t do this kind of thing before was because they assumed people would get sick of seeing the same old shit. But with Marvel’s dominance, we’ve surprisingly witnessed the opposite. People want more of this shit!

The result is that intellectual property drives the majority of studios’ decisions now. And if your intellectual property can spurn more intellectual property, even better.

Nipping at the heels of the “universe” IP approach are YA novel adaptations. Twilight, The Hunger Games, Divergent, The Maze Runner, The Giver. Publishing houses are starting YA novel brands with the explicit purpose of getting movie deals out of them. So crazy has the YA novel craze gotten, you can’t even option YA books that have 5 reviews on Amazon anymore. Desperate producers have already beaten you to the punch!

After that, you have the toy properties (Transformers, G.I. Joe, The Lego Movie), the traditional sequel franchises (Planet of the Apes, Fast and Furious), high-profile book adaptations (Lord of the Rings, World War Z) the animation properties (mainly Disney and Pixar), and the occasional ultra-concept film (Godzilla, Super 8).

So what does over-dependence on IP mean? It means fewer and fewer slots on the calendar for original spec screenplays. Which is why you’re seeing less and less screenplays being purchased. Now I’ve been reading a lot of the specs out there, the ones making big enough waves to get noticed, and the biggest reason they’re not doing well, in my eyes, is because they’re not good enough.

This stems from the majority of writers assuming their scripts only have to be as good as the movies they see on a typical summer weekend. Unfortunately, that’s not how it works. The top films at the box office were all born out of intellectual property. In other words, the people on the other end of the pitch already knew what the writer/producers were talking about. When someone hears, “Godzilla,” they know who Godzilla is. They don’t have any idea what your script, Chocolate Frank and the Huckleberry Dancers, is about. It’s just a pile of digital paper. That means the big IP project shoots to the top of the priority list while Huckleberry Frank gets stuck up chocolate creek without a paddle. The only way your script is going to get picked over a project like Godzilla is if it’s exceptional, not simply “as good as.”

Intellectual property has taken over and you, the screenwriters with original ideas, are being pushed out. Should you throw in the towel? Give in? Of course not. Adversity is the harbinger for some of the greatest creations in history. We must adapt! We must change our tactics. But I shall warn you. Not all of this advice here is sexy. We’re looking at cold hard facts so we need to consider cold hard solutions. Throw all your preconceived notions about how to make it in this industry in a box and slide it under the bed. It’s time to put on your reality pajamas and make some tough decisions.

How to compete with IP…

Solution 1: Make your own movie – Far from earth-shattering advice. But this continues to be one of the fastest ways to break in because you bypass all the bullshit gridlock Hollywood’s famous for. Movies are getting cheaper and cheaper to make. The amazing Blackmagic camera can be had for under two grand. And since you’re on this site, you already have a HUGE advantage over your competition. One of the biggest weaknesses in any low-budget film is a bad script. But you guys are writers! You know how to write a script. So write something cheap and shoot it cheap and get it out there!

Solution 2: Write comedies or thrillers. These two genres seem impervious to the IP plague. The great thing about thrillers is you can write them in multiple genres (horror, sci-fi, action, psychological), so you have a lot of range there to find subject matter you like. And comedies don’t need IP to be funny. Again, if you can come up with a clever concept (Neighbors), you can be looking down at the rest of us from your house in the hills at this time next year. These two genres are the best genres to write in if you’re writing specs, point blank.

Solution 3: The “spec universe” – The next option is one that hasn’t been proven yet, but with the “universe” approach gaining steam, I think it’s only a matter of time before it becomes the next big thing in spec screenwriting. It’s basically what “Moonfall” writer David Weil did. Off the buzz of Moonfall’s success, he used his meetings to pitch a 7 movie franchise based on The Arabian Nights.

Now there’s two things going on here. First, Weil is using an “IP” property that’s in the public domain. This allows the studio to get all the benefits of IP without having to pay for it. Secondly, he’s using the “universe” approach here to pitch the property. He didn’t come in with a single tiny spec to sell. Remember, studios have to think bigger now. They need more to bring to their investors. They want properties that are going to deliver over a longer period of time.

So look back through those public domain properties and see if anything sparks your imagination. The Count of Monte Cristo, a great book, is a popular older property that keeps getting remade. Can you come up with a franchise version of that? Of something else like it? I mean obviously you don’t want to force a “universe” onto an idea that can’t support it. But if the opportunity’s there, why not take it?

Solution 4: True stories, known quantities and IP sneak-arounds – Hollywood loves true stories. They love’em! So go out there and find a captivating true story to tell. You have 10,000 years of recorded history to draw from. I guarantee there are a few thousand amazing true stories that haven’t been told yet. Another option is a “known quantity IP sneak-around” approach. You find something that’s real and that everyone is familiar with, and you build a story around that. This is how Aaron Berg sold Section 6 for a million bucks (about the origin of MI-6), and I’m sure it played a role in F. Scott Frazier’s recent sale about an agent who worked for the agency that would later become the CIA. The idea here is to find sexy subject matter that people have heard about, and build a story around it, so it’s an easier sell, both from writer to studio, and studio to moviegoer. Once again, this is a way to write about something known without paying an IP price for it.

Solution 5: “If you can’t beat’em, join’em.” – Basically, throw out the idea of selling a spec. Instead, figure out which kinds of movies you love above all others, the kind of movies you’d die to get paid to write the rest of your lives, and write a script in that genre. So if you love movies like Guardians of the Galaxy, write a big crazy space opera. If you like Godzilla, write or make a movie about big monsters. The script will serve more as a writing sample for what you’re capable of doing, and get you out on meetings with the kinds of people who make the movies you want to write. You may not get that big splashy sale, but you get to play in the sandbox you always dreamed of playing in, and isn’t that the ultimate goal?

Solution 6: If you can’t join’em, leave’em. And write a pilot. – Pilots are so much easier to sell than specs these days. Everybody wants them. I heard even the Weather Network is jumping on the original programming bandwagon. Anybody have a spec titled “Light Rain?” As a movie lover, this used to be unthinkable to me. Who cares about TV! But TV keeps getting better and they treat writers like kings compared to the feature world. So pour through all of your movie ideas and see if any can be adapted into TV shows.

Solution 7: Write a great script. – No, I’m serious. If all else fails and you don’t like any of these options, write an awesome script about anything you want and I PROMISE you, you’ll get noticed. Just keep in mind that if you go this route, the script has to be better than if you go any of the other routes. You have to knock it out of the park. To achieve this, make sure you are BEYOND PASSIONATE about your idea. Because if you’re not passionate, you won’t pour your soul into it, and if you don’t pour your soul it, there’s little chance of it being great. If it’s not great, you’ve got no shot at competing with all those big IP properties. Also, make sure there’s a good story here. Don’t write about an entitled 25 year old white male who’s depressed because his trust fund was taken away from him (unless it’s a comedy!). Give us a real story and tell it well.

What about you folks? What do you think writers should be writing in this new era? Is there something I’ve forgotten? A future trend you see coming around the corner? Share and debate in the comments section!

Note: The newsletter will be sent out at 11:59pm (pacific time) tonight (Sunday). Check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders if you don’t see it. To get on the newsletter list, sign up here.

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: A group of galactic misfits are forced to work together to stop an evil mad man from destroying the universe.

About: Up to this point, the Marvel universe has kept things pretty conservative, bringing out its most cinematic and popular heroes for display (Iron Man, Captain America, Thor). “Guardians” is the first true risk its taken. Not only has the average moviegoer never heard of Guardians of the Galaxy, but we’re switching genres as well, from Comic Book to space operas. Writer-director James Gunn originally had no interest in directing Guardians. But after The Avengers came out, he saw the opportunity to do something cool (and make a lot of dough doing it!). Gunn’s more of an indie guy on the directing front, directing the 2010 Sundance hit, “Super,” about a regular guy who turns himself into a superhero. On the writing front, though, he hasn’t shied away from studio assignments, writing stuff like Scooby-Doo and Dawn of the Dead. The original draft of Guardians was written by unproduced “neophyte” screenwriter Nicole Perlman. Perlman got the Scriptshadow treatment for her breakout Black List script, Challenger (about the crash of the space shuttle, Challenger). It’s rare to see an unproduced screenwriter working on a project this big, but Perlman was able to get into the Marvel writer’s program early (never knew Marvel had a writing program) and pick up Guardians when no one was interested in it. Guardians debuted to a big box office haul this weekend, bringing in 30 million more than everyone expected it to (93 million total).

Writers: James Gunn and Nicole Perlman (comic book by Dan Abnett and Andy Lanning)

Details: 121 minute running time

Is Guardians of the Galaxy the new Star Wars?

It might be. No space flick has come this close in 30 years. It definitely captures the thrill of exploration the original Star Wars had. It nails the fun. It even brings something the original Star Wars didn’t have (but I think modern audiences need). It had attitude.

But before we anoint Guardians of the Galaxy as the next big thing, we should look closer. There’s kind of a “flawed masterpiece” thing going on here. For the first half of Guardians, I thought I was watching a rough cut of the film. The timing of the jokes felt a beat or two off. The characters felt forced (I’m looking at you, Rocket Raccoon). Some of the choices seemed uninspired (how many people need to shoot other people with colorful electrical weapons when they’re running away?). Even Chris Pratt, who going in was the best thing about the film, felt muzzled. Like someone kept telling him to “calm down.”

But here’s the thing about watching something truly unique. You’re not prepared for what you see because you’ve never seen anything like it before. And Guardians is so different (in many respects), you can’t quite process it yet. It’s similar to how I felt after watching my first Wes Anderson film. I couldn’t decide whether I’d just watched genius or a train wreck.

“Guardians” follows former earthling Peter Quill, a galactic scavenger of sorts, who’s been tasked with securing a tiny sphere thing that we’ll later find out has the power to destroy the galaxy. But Peter doesn’t know that yet.

Ignorantly, he tries to deliver the sphere, but is attacked by others who want it, namely Gamora, a hot green chick (when in doubt, just insert a hot green chick into your script).

A chain of events eventually leads them to Rocket Raccoon (a genetically altered human turned raccoon) and his muscle, the giant but adorable Groot (a tree that can only say three words – “I am Groot.”) Finally, there’s Drax, a muscled alien whose species takes everything literally (“Whatever you say goes right over his head.” “Nothing goes over my head. I’m too fast. I’ll catch it.”).

Our ultimate baddy, a face painted nasty dude named Ronan, finally steals the sphere away, allowing him to become super human (or super-alien I guess). He then heads to the nearest planet to destroy it. It’ll be up to our band of misfits then, none of whom really like each other, to put their differences aside and stop Ronan from turning this planet into a galactic parking lot.

Whenever you sit down to write a sprawling sci-fi flick, you need to find your focus. You need something to keep the characters and the plot centered, or else things fall apart quickly. There are a few ways to go about this, but the best way is probably the “MacGuffin Approach” a favorite of one George Lucas. You’ve seen it in films like Star Wars, Indiana Jones, and Pirates of the Caribbean.

Basically, the MacGuffin Approach creates an object of desire that everyone wants. The reason this approach works so well, particularly on the blockbuster stage, is that it simplifies things for the audience. Almost every character has the same goal (get the sphere), which is advantageous if you’re throwing a ton of information at the audience (new characters, new worlds, lots of exposition, lots of rules). If you try to give every character unique goals, it can be hard for the audience to keep track of it all.

Simplifying the plot was important because Guardians had one of the toughest jobs you’ll find in screenwriting – bringing together five totally unique characters and seamlessly and quickly sending them off on their journey

Now some of you might say, “It’s not hard to bring characters together.” But it really is. In the same way you’ll never see Justin Bieber and Bill Gates at the same venue, in a screenplay like this, where all the characters are different, it’s unlikely you’d find Raccoon Man around Painted Chick Girl. So you gotta come up with reasons they’d cross paths. And then you gotta come up with reasons they’d be at that location at the same time (it can’t be coincidence!). And then you gotta come up with reasons why they’d leave together. And you gotta do that for three other characters as well.

It all seems so easy once you’ve seen the film, but it often takes draft after clunky draft of cramming the characters together before a natural flow emerges. And Guardians didn’t quite get there. If we’re looking at 10 drafts to perfecting this first act, it looks like they made it to Draft 6. The weird Jackie Chan sphere bobble city set piece was way forced.

Chris Pratt didn’t help either. His forced opening dance routine (I swear it was like we were watching one of those leaked actor auditions) felt like 21 suits were behind the camera simultaneously yelling at him to “stop being so weird” until the take we saw, where he was as stiff as a tree. It’d be like if Captain Jack Sparrow acted only 50% like Captain Jack Sparrow. You can’t muzzle Captain Jack Sparrow!

Compare Pratt’s mechanical delivery to, say, Han Solo in Star Wars, who never once seemed to give a shit about what came out of his mouth. Solo is so iconic because he let loose. Pratt wasn’t allowed to let loose until the end, likely when those producers finally left the set.

And then something happened. I can’t pinpoint when or where it happened. But out of nowhere, everything finally gelled, especially the characters. They weren’t trying to announce their arrival anymore. They weren’t scared to take chances. They were just “being.” And once that was the case? Guardians got REALLY good.

And yeah, I’m doing it. I’m announcing Groot as one of the best big-budget movie characters in history. It goes to show how awesome showing and not telling is (Groot is so “dumb” he can only say three words – much of what he offers, then, is through action). There were these great visual moments, like after Groot vouching for Peter, Peter making a point that Groot seemed to be the only smart one here, only for Peter to look over and see Groot eating a flower off one of his limbs.

Groot takes the “Chewbacca” role and makes it even more lovable, if that’s possible. He’s such an earnest goof who only wants to protect his partner (Rocket) that we can’t help but love the guy. One of the best moments in movies this year (spoiler) is when he builds that tree nest in the end to protect everybody as the ship goes down.

What really impressed me though is how Gunn used the theme of friendship to drive the film. I thought all these guys hating each other was totally believable, and the gentle changes throughout that brought them closer together, to the point where they’re actually (spoiler) using the “hold hands” move to save the galaxy (and it working) is a testament to the excellent mix of character development and theme in the film. Shit, I even got teary eyed when Groot says (spoiler) “We are Groot.”

I don’t know if Guardians was shot in order or not, but it’d make a lot of sense if it that was the case. At the beginning, everyone seemed tense and forced (including the director), like they didn’t want to be Marvel’s first big bomb. But as the movie went on and everyone got comfortable, the film started to shine. It’s not perfect, but these types of movies never are. In fact, their weaknesses end up becoming strengths, as they’re woven into the re-watch fabric of the legacy.

And I’m going to say one more thing about this film before I go. Because it’s one of the few times I’ve seen it in the past 20 years. For some reason, at some point in history, summer blockbusters became “one and done” movies. They were made to work for one weekend and that’s it. Gone were the Star Wars’s, movies so rich you wanted to keep watching them over and over again. Guardians is the first summer movie I’ve seen in forever that wasn’t interested in being one and done. It wanted to be rewatchable. It wanted to do more. And I hope its success inspires more summer movies to do the same.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: With a giant blockbuster flick that requires conveying a lot of information to the audience, instituting a MacGuffin (an important item that all the characters, good and bad, are after) is one of the easiest ways to simplify the plot.

What I learned 2: Embedded Goals – Embedded goals are goals your characters need to achieve in order to get back to the main goal (in this case, getting the sphere). So, early on, our group is thrown into prison. Obviously, the main goal needs to pause while they deal with this problem. They must accomplish the embedded goal (escape the prison) to get back to business. Embedded goals help add texture to the story. If your characters are only pursuing one single thing for all 120 pages of a screenplay, things can get monotonous quickly.

One of you suggested this in the comments the other day and it sounded like a wonderful debate. The two biggest geek shows on TV are Game of Thrones and The Walking Dead. My guess is that both shows have a lot of crossover viewers, which means most of you are educated enough to offer your opinion on both. Therefore, I shall ask: Which is the better written show, The Walking Dead or Game of Thrones? Notice I didn’t ask which is the “better” show, but which show is better written.

In my eyes, this isn’t even a fair fight. The Walking Dead is a much better written show. I’ve never felt more worried for characters than I do during this show. At any moment, they’re in danger from either a zombie or fellow human attack, which leads to that necessary discomfort the audience must feel in order for the story to work.

The scene-writing is also top-notch, always so clever. They’re constantly setting up complex situations that don’t have clear resolutions, keeping you on the edge of your seat for up to 10 minutes at a time. My favorite scene of the year (in anything!) is the one where Rick sends his son and Michonne out to get food while he takes a nap in an abandoned suburban house. In the interim, raiders show up and take over the house, forcing Rick to hide.

If he tries to leave, they’ll easily catch and kill him. If he doesn’t, his son comes home unaware the raiders are there and they’ll kill him instead. These are the best kinds of scenes because there’s no solution. Every road traveled leads to failure. And if you set up that kind of situation, you better believe your reader/viewers are going to stick around to see what happens. The Walking Dead is filled with cleverly thought-out scenes like this.

Like any show, The Walking Dead has some good characters and some not so good characters. But on the whole, they’re good. Watching Rick fight a daily battle against losing his humanity is one of the better inner conflicts I’ve watched a main character go through. Watching inventive characters like the zombie-carrying sword-wielding Michonne emerge is beyond delightful. And meeting the best villain of the last decade in the endlessly complex “The Governor” was the cherry on top of Season 3.

Finally, The Walking Dead is really good at structuring its storylines. There’s almost always an episode goal (Find a way out of the house without the Raiders seeing you), a season goal (Get to the safe city, Terminus), and a series goal (survive and find ultimate safety) to keep everything focused and on track. There’s never a point in The Walking Dead where you’re saying, “Wait, what’s going on again?” It’s always clearly laid out.

Game of Thrones is a completely different animal, but good in its own ways. Its number 1 asset is its mythology. With The Walking Dead, the mythology is being built as we experience it. There’s not a lot of mystery there. But some of the things affecting the characters in Game of Thrones go back thousands of years. For that reason, you feel like you’re living in a truly immersive world, and every episode is a gift you get to unwrap to find out more about that world.

Another reason I love Game of Thrones is its restraint. Unlike certain fantasy franchises that throw a million pieces of fantasy at you a minute (orcs, spells, invisibility, giant spiders, talking trees), Thrones TEASES their fantasy elements. We hear about dragons, White Walkers, people coming back from the dead. But because these things are only hinted at, we don’t grow numb to them after five minutes. Instead, we eagerly anticipate when we’ll get to see them, which is another reason we’re so excited to keep watching.

Also, the relationships the show creates are captivating. Every character is connected to every other character in some way. To give you a taste, Cersei Lannister, the Queen, is secretly sleeping with her brother Jaime Lannister. We later find out that the three children the King and Queen have are not the King’s. They’re all from Jaime, which makes them inbreds. One of these children, the evil, unstable Joffrey, becomes King. Rumors spread throughout the land that Joffrey is the inbred son of Cersei and Jaime. Cersei must do everything in her power to keep this information from getting to Joffrey, since unstable kings who find out that they’re inbred probably aren’t going to take it well.

Finally, there are a lot of standout characters on the show. The empowered “mother of dragons,” Khaleesi, is exciting to watch as she goes from underdog outsider to plotting her Iron Throne takeover. Tyrion, the “imp,” played by Peter Dinklage, is lovely to watch if only because the character is so unexpected. Occasionally he’ll play the coward, only to follow it up by slapping the king. Arya Stark, the young daughter of the slain Ned Stark, is pulled from her family and must survive out in the wild. There’s the impossibly cold Cersei Lannister, whose utter hatred for the world drives her every action. Her son Joffrey is so evil, you can’t look away, lest you miss him chopping someone’s head off. The always manipulative brothel owner, Littlefinger, charms with his whispering schemes and careful chess moves in order to keep his place in power. There’s always a character to look forward to here.

But here’s why Game of Thrones doesn’t compete with The Walking Dead. Whereas The Walking Dead is always clear – we always know what’s going on and can therefore participate in every aspect of the story – Game of Thrones is too often confusing. And it all comes back to one issue – there are too many characters.

In a show like this, a show that DEPENDS on you knowing the intricate details of every relationship, being confused about who’s who can destroy the enjoyment of an entire episode. If I’m only just remembering that Robb Stark wants to kill Character A at the end of a scene where two characters are discreetly talking about Character A, I’ve missed the whole point of the scene. This happens a lot in Game of Thrones.

Tons of characters also means entire episodes go by without us seeing some of the characters. So when we finally come back to them, we barely remember what they’re up to. Again, two or three scenes may go by before we recall what they’re doing in this location in the first place. For example, I was watching Jon Snow traverse the North Mountains for an entire episode before I remembered, from a couple of episodes ago, why he was sent there in the first place.

No matter how you spin it, this is bad writing. One of the requirements of writing any story is that the reader always understand what’s going on. If they don’t, it can only be because you, the writer, don’t want them to for some reason. In other words, it’s the writer’s choice. But a lot of the confusion that comes from Game of Thrones is not due to the writer’s choice. It’s due to there being too many characters and too many camps to keep track of.

Another problem with Game of Thrones is that it errs on the side of “telling” instead of showing. It’s gotten better at this as the show’s gone on. But in the first season, there were endless scenes where two people were in a room talking. Therefore, instead of seeing troops move across the land, we hear two people TALK ABOUT troops walking across the land. Indeed, every other scene appears to be strictly exposition, which would often grind the show to a halt.

What’s interesting is that this exposition is a result of choices the writers made a long time ago. If you’re going to have a dozen factions all vying for the throne, you’re guaranteeing you’re going to have a ton of exposition. The Walking Dead doesn’t have that kind of complexity in its endgame. The endgame is simply, “survive,” so its exposition is often minimal, and we can focus more on the fun stuff, which is showing and not telling (characters getting into dangerous situations and then trying to get out of them).

Personally, I think both shows are great in their own way. But The Walking Dead is a cleaner more action-oriented story that can just “be,” whereas Thrones has to talk you through much of its world to get to its payoffs, which can sometimes feel like work.

What do you think? Which is your favorite show and why? Make sure to support your opinion with valid points about the writing. And yes, this may be the nerdiest post I’ve written this year.

note: I’m on Season 2, Episode 5 of Game of Thrones. Please note spoilers in your comments!

Justin Lader is the writer on the twisty-turny breakout Sundance hit, “The One I Love.” This is his first produced credit. The film stars Mark Duplass (Zero Dark Thirty, Safety Not Guaranteed) and Elizabeth Moss (Mad Men). The film hits VOD and Itunes on Friday August 1st and theaters on August 22nd! Make sure to see it!

SS: First off, Justin. Congratulations! How did this journey begin for you? When did you start writing?

JL: Once it became apparent that anything involving athleticism wasn’t a viable option, I took an interest in the arts. Growing up I would manipulate the kids in my neighborhood into thinking we were playing cops but I’d really be placing them in certain roles, constructing a story and we’d be improvising. I was also a big GI JOE and wrestler action figure guy. I’d lock myself in my room and use them not as GI JOES or wrestlers, but as characters in stories I was making up while playing with them. That’s all well and fine until you reach the fork in the road called middle school and you had to choose between GI JOES and girls.

At the time, I didn’t realize I was telling stories, I didn’t think of it like that. Writing wasn’t something I ever considered. It was just a thing you had to do for school and you’d put it off until the very last minute (something which unfortunately still hasn’t changed much). In high school I did theater and that was fun but acting never really came natural. Basically I’d be on stage just trying to remember what my next line is and hoping to deliver it in a way that didn’t humiliate myself. It wasn’t until we were given the option of doing a monologue or writing our own for a class midterm that I realized writing was a viable option for me.

The thought of memorizing a monologue was unbearable so I leaped at the opportunity to write my own. I was obsessed with Andy Kaufman at the time so my idea was I’d write what would seem to be an intense personal monologue about loss. That way people would be sympathetic to me and there would already be a built in bit of awkwardness and discomfort in the air. Then I had a friend of mine who was also in the class begin to heckle me halfway through. There was a nice slow build to it; other students began to get upset and annoyed. I began to stammer on stage like it was affecting me. It all culminated with me confronting him. The teacher didn’t even know about it. People in the class were really freaked and confused when they realized it was all a put-on. I got an A and said no more acting. It’s all about story telling. From there I went to undergraduate film school at the University of Central Florida and majored in Film. After that I applied to AFI and was accepted in the screenwriting discipline.

SS: At least you didn’t sit next to people on airplanes and show them gruesome photographs of plane crash sites, as Kaufman was known to do. So how did you get into screenwriting specifically?

JJ: I always loved movies and TV shows. It was my life. I’d watch everything. The undergrad/grad school experience was really eye opening for me. My college film program at UCF was very independent minded. At the time its claim to fame was the Blair Witch guys came out of there. Basically you wrote, directed, produced, edited, and sometimes acted in your own shorts. Permits didn’t matter. It was gorilla filmmaking and it was a lot of fun. At the time, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to dive in as a writer/director or just a writer. I knew anything technical wasn’t possible for me. It still takes me about 35 minutes to set up a C-Stand.

SS: Me too!

JL: Those things are impossible. But I did notice something important fairly early on. Most of the other film students had exceptional knowledge and skill on a technical level. Leaps and bounds above me. But they didn’t seem to get excited by story. It was almost as if the story was an afterthought to all the cool technical things they wanted to do. So after undergrad when AFI was an option and I had to actually pick a discipline and stick to it, I thought about that. I thought about all the headaches of going through pre production on a short film – raising money, securing locations and vendors, casting actors that most of the time just want something to add to their reel, and I realized that I didn’t want to go through all that again.

I also thought that after two years at AFI, leaving with a couple of polished feature length screenplays and a TV pilot might position me better to hit the ground running as opposed to a short film, which usually leads to somebody, at best, watching it and liking it and then asking what’s next. So I decided to apply to the screenwriting discipline. And the AFI film experience was the polar opposite of the UCF film experience. At AFI, everything was about permits and narrative and the Hollywood way of telling stories and turning those stories into movies. I used to joke that AFI required a permit just to use their bathroom. So in a lot of ways I felt like I got the best of both worlds as far as the film school experience goes. However, I also got the best of both worlds as far as film school debt goes, so there’s that too.

SS: Well, we’ll try to alleviate that a little bit (Scriptshadow readers, go see this movie!). So during those early days, what was the most challenging thing about screenwriting for you?

JL: I’d say finding my voice. That didn’t happen for me until AFI. Mainly because film schools try to force 3 act narrative filmmaking into the paradigm of a short film. And that’s brutal. A short film is its own mountain to climb and very different from features. I think that’s one of the big mistakes most film schools are guilty of and why a lot of short films you see from even prominent film schools tend to feel long and not work. At undergrad I wrote my first two features. They were the standard coming-of-age scripts. I was lucky to get those out of the way early. Then at AFI, I started to really define my voice and the types of stories that excite me. Something as organic as finding your voice, on paper, doesn’t seem like it should be the biggest challenge, but for me it was. It took a while.

SS: Okay so how many scripts had you written before you finally felt like you were “getting” screenwriting?

JL: My first feature at undergrad was coming-of-age. My next script was a pilot, also coming-of-age. Then, through a professor who became a mentor, I was hired by an author to adapt his novel into a script. That, too, was coming-of-age. So like I said, I REALLY got that out of my system. At AFI, things started to click for me once I realized the types of stories I wanted to tell (bigger hooks that led to intimate unpredictable stories). And to this day, Charlie (director of The One I Love and my collaborating partner) and I look for these types of stories whenever we’re about to break a new script.

SS: Can you remember a specific moment when things really started to click?

JL: My thesis feature script at AFI was a screenplay called Fighting Jacob. At the time, I was pretty unhappy for a lot of reasons that don’t really matter for the purposes of this. And I wondered if being unhappy was also a contributing factor in being a writer. Then I was scared that if I ever found happiness, I wouldn’t be a good writer anymore. Now, if I had this idea back when I was in undergrad, I would’ve written a very literal story about an introverted writer who struggled with his art and emotional growth. You know, a coming-of-age-story. Not wanting to do that, an idea occurred to me and it led to what Fighting Jacob eventually became.

It was a story about a neurotic hypochondriac who just happened to be one of the most promising up-and-coming boxers on the amateur circuit – He won’t throw a punch until his opponent hits him ten times first, and after the post-fight physician checks him out he’s more concerned with the mole on his chest being benign than the bruises he got from the fight. Basically you have a protagonist that’s physically Jake Gyllenhaal but mentally Woody Allen. It’s his pent up anxiety and neurosis that makes him a monster in the ring when he lets it out. The Jewish version of Raging Bull. Anyway, he meets a girl, falls in love and begins to feel happiness for the first time. As their relationship grows, his quirks and OCD tendencies begin to go away and he realizes he’s not fighting as well anymore. And the story then becomes about him struggling with whether or not he has to be unhappy to be a good fighter and does he have to choose between boxing or the girl…. So basically, it was taking something that felt real and honest to me, but dramatizing it in a way that narratively (hopefully) had a fun sort of hook to get people interested.

Then, really quickly, the other thing that clicked was the idea of taking something familiar and subverting expectations in a hopefully interesting way. We had to write a couple of spec scripts of existing shows in a TV comedy class at AFI. I have two television idols (more like obsessions really) and they’re David Chase and Larry David. So naturally I wrote a Curb spec. My premise was Larry agrees to write a Seinfeld reunion episode just to impress an attractive studio exec that was at the pitch meeting. (This was in between seasons 6 and 7 so I had no idea they were actually making another season with a Seinfeld arc). So I wrote that spec and then felt wonderfully vindicated when I learned that the actual premise of the next season was the same thing. As someone who is usually very hard on himself, the cross-over moments between my script and David’s made me feel like I was doing something right.

And the other spec I did was an East Bound and Down that centered around Danny McBride’s character learning that a Hollywood studio was making a biopic about his life as a troubled train-wreck former ball player and the studio casts Vincent Chase to play him. Wishing it was someone more bad ass like Micky Rourke, McBride’s character tries to get Vinny Chase (and the Entourage) to OD on drugs when Vince comes to “observe him” as preparation for playing him in the movie. So it was merging an East Bound and Down spec with an Entourage spec, but in the tones and universe of East Bound and Down. Writing this spec led me to realize that there’s a level of unpredictability that comes when playing within different tones that don’t normally go together. The tricky part is executing those different tones properly. Because there’s good unpredictability and bad unpredictability. Left of center is great; out of left field is not…. These three scripts were what led to my first opportunity to have representation.

SS: Ooh, I like that line (“Left of center is great; out of left field is not….”). So true. Moving on, can you tell us how you eventually got your agent/manager (or both)?

JL: I got my first manager through a friend who read Fighting Jacob and my Curb spec. He very graciously passed it along to a friend who happened to be a manager. I was in my last year at AFI and having a manager that early was thrilling. Ultimately, we had different philosophies when it came to the types of movies I should write. I’m pretty miserable when I’m struggling to write something I love so I don’t want to even think about the unbearable bastard I’d be if I was writing something I wasn’t passionate about. His mentality was more SELL SELL SELL, which is totally fine but being a twenty-four year old coming out of AFI, I was looking more for a manager who would nurture a new writer and work to build a career of collaboration. Eventually, I met Charlie (the director of The One I Love) and he read Fighting Jacob and we hit if off both personally and creatively. We set out for that to be the first movie we’d make. He’d direct it. During that process I signed with another manager, who I’m still with currently. And Charlie and I eventually signed with an agency because we were close to selling a TV show and it was time for agents. We ended up selling a pitch to CBS that never went anywhere and soon after we sort of parted ways from the agency in a very non-dramatic way. Then about 3 years ago we signed with a new agency (ICM) that’s been wonderful and that’s been our happy home ever since…

SS: Is there anything you learned during that process?

JL: Probably not to stress too much about agents and managers. I remember, especially in film school, the thinking is that agents and managers are the answer. And then the career begins. The reality is that agents and managers can’t do much for a new writer until the new writer does something for himself. Obviously there’s that massive spec sale exception. But by and large, it’s about creating your own opportunities AND THEN you have agents and managers to help facilitate those opportunities once they come. It’s a bit of a catch-22 because you can’t really break in without an agent or manager but agents and managers don’t really want you until you break in. My relationship with my agents and my manager has been invaluable since we’ve made this movie. Once you have opportunities and it becomes about navigating a healthy career path, making the right decisions creatively and career-wise, you count on agents and managers. But nine times out of ten, and this is true for pretty much everybody I know who also has managed to break in, that first opportunity that gets your career going comes from you.

SS: Okay now this is the stuff I’m particularly interested in. Most people go the traditional route of sending specs out and either getting a sale or getting assignments. But for these more independent/Sundance type projects, the process can be a little more homegrown. Can you tell us how The One I Love came about?

JL: Charlie and I spent the better part of 5 years trying to get Fighting Jacob off the ground. We had a lot of close calls. We even had financing and a pretty wonderful cast lined up. The problem was it was one of those projects in budgetary no man’s land. At the time, I actually thought I was being smart or strategic by writing a high concept indie in the 2 and a half to 3 million dollar range. What I didn’t know was that nobody wants to finance that. At the time, the big boys don’t see an upside in investing that small of an amount. It’s not worth it to them, they want to invest in bigger indies, more closer to ten. And for the people who do finance low budget indies 2-3 is way too expensive and risky.

SS: Wait, let me stop you there. So it’s bad to write a 2-3 million dollar indie film? That budget will always be passed up because it’s stuck in no-man’s land?

JL: It’s fascinating because the paradigm is constantly shifting; even from only a year or two ago. At the time we were gearing up for FJ, we had the script budgeted for about 2.5 I believe. Not sure exactly, that’s ballpark. It was tough because independent financiers tend to either wanna go below a million or over 6 or 7. That was the case a few years ago. It might be a little different currently. If you had a big name actor that would make it easier. But even that was more of a scientific thing as opposed to a prestige thing. You could get a decent name but if there was no foreign value to the actor, the money folks didn’t really care. It was important to sell off foreign territories so investors can get their money back before the director even says action….

Now currently, and I do think this plays a factor for high concept indies, the budgets can fluctuate based on things that have nothing to do with the script. And that’s something the director discusses with the team beforehand. There could be a version of a film that’s made for 7-8 million and a version made for 1-2; and this gap in $ has absolutely nothing to do with the script, I’m talking about not changing a word. There’s obviously a multitude of pros and cons but overwhelmingly most directors go for the 1-2 million version even though that limits them in many ways.

The short reason why — Control. That amount means the director can pretty much cast the movie the way they want and make the movie the way they see it. But most importantly, once you go beyond 1. 5 (I forget what the exact number is, may not be 1.5) you have to go union. I’m talking teamsters and the whole nine yards. If you make a movie for less than (1.5) you can sidestep all the fees and hoops; and the main reason that’s appealing is because every cent of that budget goes on screen. If you make a move for 3, most of that goes to all the union stuff and never makes it to the screen… From my experience, a nice high concept indie with a great role for a name actor, kept to within 1.5 is a great place to be. Studios that acquire movies on the festival circuit are paying less and less these days. I know of some movies that had decent offers from big studios but COULDN’T sell because the financiers would lose money on the sale. So the filmmakers had to pass. Crazy stuff.

SS: Wow, that’s fascinating. Okay, sorry for interrupting. You were talking about trying to get Fighting Jacob off the ground.

JL: Right so Charlie and our manager were persistent, passionate and smart. Like I said, we got casting and financing and were gearing up for pre-pro when financing fell through and we had to “push” the start date. What I very quickly learned was that “push” is actually code for “never gonna fucking happen.” While that was going on, our agent (who happens to be Mark Duplass’ agent also) gave Mark Fighting Jacob to read. He then met with Charlie and the two of them hit it off. Mark and Charlie had similar sensibilities and Mark explained his model and approach to making low budget films. It was a natural fit and Charlie was so hungry to make something. Mark said we’d hear from him. And we did. The three of us hopped on the phone and we all clicked. Then we started talking about concepts and an idea emerged. Mark then let Charlie and I go off to break the story. (That’s how our relationship works. Creatively it’s wonderful. We break the story together so it comes from us both, I go off and write then he makes what I write a million times better as a director)….

So I put together a ten page document that laid out the ground work for the story in the hopes that it would entice Mark to proceed with us. He was pleased and we were off to the races. This happened in October (not of this past year) and we wanted to shoot the movie in April. Now at this point we knew what we were dealing with in terms of budget, location, and if we wrote a good story – our lead actress. So it was about writing very quickly to make an April start date. Since Mark is one of the busiest people on the planet, if we didn’t make that date, the movie would have been “pushed.” So Charlie and I basically said that if this movie doesn’t happen it won’t be because we didn’t deliver on our end. So we delved into the story and broke it very quickly. I wrote what ended up being what I believe was a 55 page document that we called a scriptment.

SS: Okay, so kind of like what James Cameron does.

JL: For me the inspiration was more what Larry David does on Curb, but yeah. And I didn’t include dialogue in it. I would suggest certain lines but it was all in the exposition and scene descriptions. It had every scene, what was happening in the scene, what the characters were going through externally and internally. It built the narrative thread of the movie. That was completed by the end of October. Our producer Mel came on board after reading it. Mark sent the script to Lizzie (Elizabeth Moss) who read it and wanted to do it. Timing-wise she was finishing up Mad Men literally the day before we were to start shooting, so it felt like the stars were aligning.

As pre-production rolled along it became apparent that the last 30 minutes of the movie required full scripting for practical reasons that would have made improv difficult. So I scripted the last 30 pages, which was an interesting exercise because while the scriptment was very carefully plotted and detailed, I hadn’t heard these characters interact and a lot of that interaction was going to come directly from Lizzie and Mark. It ended up working out and we shot the movie that April.

Like I said, this was a heavily plotted movie with a TON of scenes so we realized on set that we didn’t have the luxury of time to go through long exploratory scenes. It became apparent that I’d be of use scripting the next day’s scenes out the night before. Even if Mark and Lizzie added their own lines, it served as a nice blueprint for pacing. We’d get a sense of how long the scene should feel beat wise – Like, the first few lines there’s room to play, but by line four “this” needs to be said so the scene pivots into this bit of information which carries us into the next scene. I would write those pages, hand them to Mark, Charlie, Lizzie, and Mel while the crew was prepping, and these pages would function as our starting off point and we’d all collaborate and find the scene from there. It was an incredible amount of fun and it kept things fresh and exciting. It was collaboration in the truest sense.

SS: Whoa, that’s a really unique approach. I don’t think I’ve ever heard of someone doing it that way before. All right, so, if you were giving advice to writers out there, would you tell them to go that more traditional route of trying to get a project made at a studio or should they go the indie route?

JL: That’s tricky. It depends on the types of stories you want to tell as a writer. I mentioned earlier that David Chase was another hero of mine and a major influence. I was in high school when the Sopranos started and for some reason what he was attempting to do with that show immediately clicked for me. He took the hook of a mob story and used that as a way into exploring the things he wanted to say about family, work, fatherhood, and being an American male mid-life in the late 90s and early 2000’s. The main character just happened to run a crime family. What that show did is something that I think independent films can do now. I think it’s an exciting and new time in independent filmmaking.

In the mid 90’s you had the boom of indie filmmaking where studios learned that certain movies could be acquired from elite festivals and find mainstream audiences. And that’s sort of been the paradigm ever since; a little bit of survival of the fittest – Some movies would get acquired by a studio, others would only exist in film festivals. Of the films acquired, some would break through and find an audience, and others would struggle. Now, with VOD and iTunes, same day releases, and everything in between a new model to distribute independent films is on the horizon and beginning to emerge. Of course it requires a little trial and error, and there are a bunch of kinks that still need to be worked out, but I’m incredibly excited to be starting my career during this new boom of indie filmmaking.

Look at something like Snowpiercer. It’s a tremendous success, well deserved. But just from a story standpoint, in premise alone, it’s something that could have conceivably been a big studio tent pole. But they made it independently, which allowed them to take a high concept premise and take it in a direction that’s interesting and unpredictable. And that’s what I was talking about when I mentioned the Sopranos earlier. Part of the DNA of that show was the fact that anything could happen at any moment. It used to be that big ideas were meant for big studios. If you made a “genre” indie, it was meant to get the attention of the studios and help you break in. If you were an indie filmmaker by nature, the perception was that you were dabbling in avant-garde filmmaking that didn’t necessarily have a strong emphasis on narrative. But that’s not the case anymore. So if you’re the type of writer who conceptualizes big ideas and is interested in executing those ideas into a subversive story that appeals to audiences while managing to also keep them on their toes, I think it’s a very exciting time to consider the indie route.

SS: This next question is tricky because I keep hearing this film has a big twist that turns it into a different genre. I don’t want to find out what that is because I want to be surprised when I see the film. But I’m curious if making that choice was easy to you or difficult, since aggressive choices in movies are a hard sell. People usually like to know exactly what kind of movie they’re paying for. Did people tell you, “You’re crazy. This is too strange. We need to rewrite it to be more traditional?”

JL: It was just the opposite actually. We realized that our take, or hook, to hang our story on was exactly what was going to work in our favor. Another reason Charlie and I work so well together is our approach. I tend to think in terms of story. Wouldn’t it be cool if… What if this happens… And then.. etc… Charlie is wonderful when it comes to character. So we complement each other nicely. Once we had the hook of our movie we made it a point not to just rely on it to carry the audience through the rest of the film, but to also build on it. Constantly build and not just tread water. We also reverse engineered the character component and emotional story to compliment what you’re talking about. And what that gave us was taking something that is high concept and making it universal and emotionally true. That was our mandate. As long as the characters were going through the emotional equivalent of the hook or twist or whatever you want to call it, we were confident we were making the right choices.

SS: Can you tell us a little bit about your process? (Do you outline? If so, how extensively? Do you focus mainly on structure? Or character? Or theme? How long does it take you to write a first draft? And then eventually a finished script?)

JL: Clearly The One I Love was not my typical process and was its own thing. Usually it’s a full script from the get-go. The One I Love came together fast. The new one I’m finishing up took a while to find. For me, I think it’s much better to have an idea of what the story is and more importantly where it goes so you have some kind of road map. That’s just me. Some people crank out a first draft very quickly and that turns into their outline. I find I write better and the process is easier when the story is broke before I begin writing. It saves me time and anxiety. And anxiety is something I’m definitely not in short supply of. When dealing with high concept ideas, it’s important for me to tap into that universal theme I really want to explore within the concept. It helps me write because it grounds a big idea into something human. Like Eternal Sunshine. That’s a movie about getting over a break up. So theme is important, especially when the premise isn’t literal.

SS: What are some of the most important things you’ve learned about screenwriting over the years, things that have really helped you as a writer?

JL: I find the best lessons about something specific also apply to life in general. It’s important to be self aware as a writer. And to be reflective and honest enough to not be on either extreme of the spectrum – What you just wrote probably isn’t the best, most original, thing you’ve ever done. And also, what you just wrote probably isn’t the biggest waste of time and load of crap ever typed on a Macbook. It’s important to be dramatic in your writing but not in your analysis. It’s easier said than done, and lord knows I struggle with that. Being able to accurately assess your work in an honest and critical way is something most writers (even great writers) struggle with. The workshop process really helps with that. You’re able to understand notes, navigate how to react to those notes, and most importantly find the note behind the note. Because nobody knows your script as well as you do. So often you’ll hear a note that might not be well articulated but the emotional visceral response BEHIND the note is something that you should consider. That’s why I really like this site. Whether I agree or disagree with a criticism or lesson, ultimately this website is a wonderful tool in learning how to reflect on the writing process as opposed to just fixating on the finished product.

SS: Yeah, go Scriptshadow! ☺ So what was it like seeing your movie for the first time? Did it look and sound like you imagined it in your head? Or was it completely different?

JL: That aspect of this was a fairy tale in every sense. Woody Allen said that an idea is at its best in your head because the imagination has no production limitations. Being on set every day, soaking up and absorbing everything I could from Mark, watching Charlie direct something I wrote with the skill and confidence of a veteran filmmaker, and having Lizzie convey a complex emotion I labored over describing in the script all in just a look was better than anything I was able to conceive of in my neurotic brain. And that was just the experience of making it. Which terrified me. You always hear that the best on set experiences eventually translate into the worst movies. Everyone had a bitch of a time making Titanic, and that turned into a big success. Everyone had a blast making Dunston Checks In, and that turned into Dunston Checks In. So when we premiered at Sundance and it got the reception it did, I was humbled and thrilled. Then I immediately scheduled a physical with my doctor because there’s no way something this wonderful and amazing could happen to me that didn’t result in the karmic balance of some form of cancer. … But I turned out to be clean.

Thanks so much for this. Have a lot of respect and admiration for this website. This was fun.

SS: Thanks Justin. Can’t wait to see what you do next. ☺

note: Justin will occasionally be checking in on the comments. So if you have a question for him, feel free to ask.

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: A reluctant boy genius finds out his step-father, who’s building the world’s first artificially intelligent computer, has been keeping a terrifying secret from him.

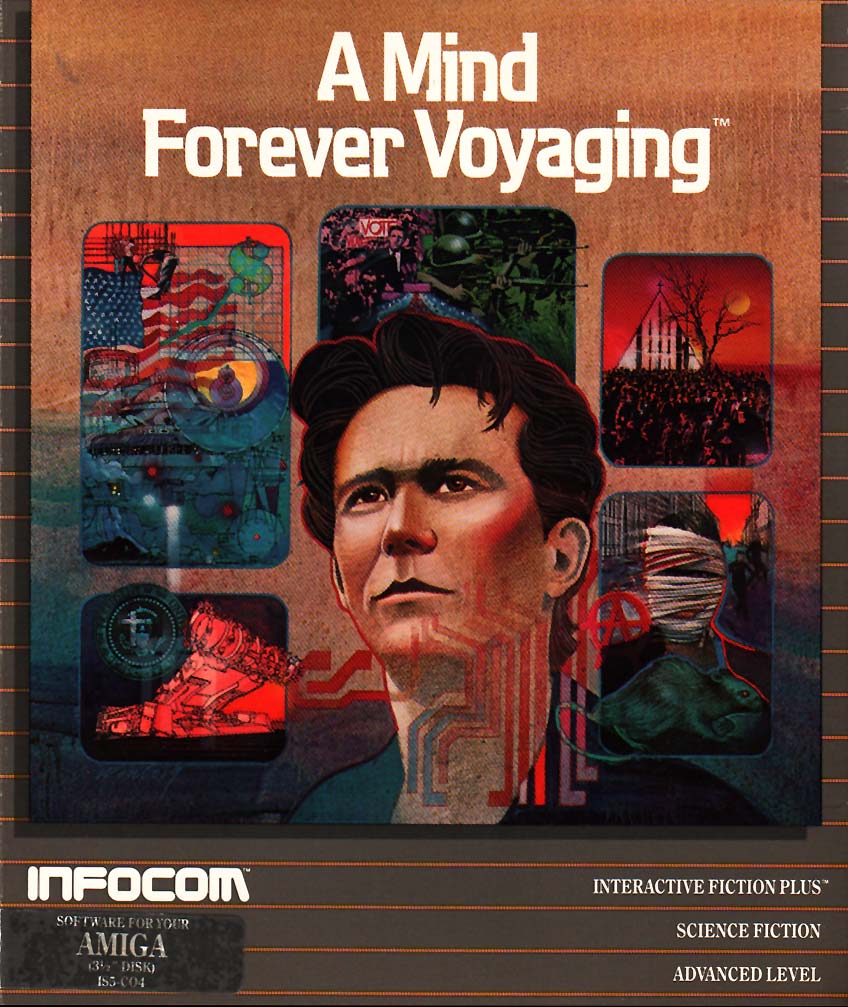

About: Gary Whitta sold his spec script Book of Eli five years ago. He went on to script After Earth for Will Smith. He’s since been tabbed as the scribe on one of the Star Wars spin-off movies. This is one of his earliest scripts (written even before Book of Eli). The script is based on an 8-bit Infocom story adventure from the 80s. A Mind Forever Voyaging is thought of as the pinnacle of the adventure stories that came out in that era. Whitta took the unique step of writing the adaptation without the rights, hoping to use the finished product to acquire the rights formally. But apparently Activision, who owns the Infocom universe, has zero interest in adapting their products to film, which is bizarre when you think about all the money that could be made. Anyway, Whitta kindly put the version of his script online for everyone to see. He still hopes to get it made one day.

Writer: Gary Whitta (based on the story by Steve Meretzky)

Details: 117 pages (2002 draft)

If you’re like me, you became a lot more interested in Gary Whitta once it was announced that he’d be scripting a Star Wars film. I know a little about his history (he used to work in video games before moving over to screenwriting), but all I have to go on is Book of Eli and After Earth. I’ve stated before that I thought Book of Eli was a solid spec and that After Earth was a much better screenplay than it was a movie.

Still, two scripts wasn’t enough to go on. You needed a tiebreaker.

Enter “A Mind Forever Voyaging.” I’d heard of “Mind” before and while I’d never played those 8 bit adventure stories, there was something exotic about them that I always found appealing. The artwork on this one, in particular, implies a vast and rich story. It’s time to finally find out what that story’s about.

Professor Abraham Perelman, 55, is working on the first ever artificially intelligent computer. It’s a giant unseemly thing consisting of so many computers and components that it needs to be kept in an underground warehouse.

Perelman is eventually approached by a senator who’s heard about his research. Perelman explains to the senator that in 12 years, the computer will be so sophisticated that it’ll be able to predict the future. 12 years is right on track for when the senator plans to run for president. Which means, with the aid of this computer, he’ll be the first president who can actually guarantee his promises.

Meanwhile, Perelman enjoys time with his two step-sons, Jason, and Perry. In short, Perelman lost his previous family to murder. And this family lost their father to jail. So they sort of clicked together like the depressing version of The Brady Bunch.

While Jason rejects Perelman as his step-father, Perry makes a real connection with him. Even when Perry shows tremendous mathematical prowess, Perelman, a math buff himself, supports his choice to be a writer instead.

Time passes and we watch Perry grow from 8 to 11 to 16, to 20. As he grows up, the Senator keeps moving up the political ladder. Finally, Perelman drops the big bombshell on Perry. The reason he’s a math superstar? That he can solve any equation in the universe? He IS the computer Perelman’s been building. Apparently the only way to make that computer truly AI was to make it believe that it was real. Perry is the manifestation of that experiment.

Also, since the Senator is finally running for president, Perelman needs Perry to look forward in time for him and find out what the world’s going to be like in five years. When Perry does this, he sees a world where the Senator has unified all states into one. He’s also restricted most freedoms in order to keep America “safe.”

When Perry tells Perelman this, he can’t believe that his step-father is actually on board with it. From that point on, Perry decides to take things into his own hands. Since he IS the computer, he’ll write his OWN program. And he’s going to change everything to the way HE thinks it needs to be changed.

A Mind Forever Voyaging is one of the stranger scripts I’ve had the pleasure of reviewing. You see, it has one giant problem inherent in it. But that problem might also be necessary for the script to work. Talk about a conundrum.

Let me explain. The hook of this screenplay – a kid (or young man) learns that he’s actually the living brain of a computer – doesn’t arrive until page 80! That’s SUPER LATE to get to your hook.

Explaining why this is a problem is tricky because it depends on what you consider to be your story. Is your story the aftermath of a kid who finds out he’s a computer? Or is your story everything that leads up to that point? To me, the far more interesting story is a kid who finds out he’s a computer (and the subsequent aftermath). For that reason, that twist needs to show up WAY EARLIER, preferably around page 30 (the end of the first act).

For comparison’s sake, look at a movie like The Matrix, where Neo learns he’s living in a computer. Neo finds that out on page 30. Would The Matrix have worked had Neo figured that out on page 80? My guess is no.

The catch with “A Mind Forever Voyaging,” however, is we don’t start with a grown man. We start with a boy. And it’s because we watch this boy grow up through the years that the shocking twist of him not being real hits us so hard. That doesn’t hit us nearly as hard if we reveal it on page 30.

This is a classic example of one of those big screenwriting problems that doesn’t have a perfect answer. If you move the “boy is a computer” reveal to the end of the first act, it doesn’t have the same weight. But if you keep the reveal at page 80, you’re making the audience wait way too long before anything happens.

When faced with this problem, I always err on the side of “get to the story faster” and I’ll tell you why. Because when someone is reading your script or watching your movie, it always feels slower to them than it does to you. You might think, “Oh! Page 30!? No way! That’s way too early!” But in the reader’s reality, things are taking a lot longer.

Think about it. When’s the last time you read a script or watched a movie and said, “MAN! This is going by WAY too fast!” 99 times out of 100, a script is moving too slow, right? So you want to assume that with your own writing as well.

But, if you absolutely REFUSE to meet the Page 30 deadline, a last resort is to push your plot point to page 45. It’s still early enough to keep the story moving, but late enough to give the proper amount of “time passing” before the event occurs. Also, that way, you still have 70 pages left to play out your unique world post-reveal.

Despite these criticisms, I still want to see this movie. Once we DO get to that reveal, things start to get pretty trippy. Like we’re jumping back and forth in time, there’s a struggle for control of the computer, there’s a little Inception thrown in for good measure, a little 2001. And then there’s this creepy sci-fi atmosphere that’s present throughout. To that end, Whitta really captured that eerie empty feeling you get as a story unravels before you in MS-DOS green-on-black text. I definitely felt that here. And along with some complex characters and an unexpected storyline, I don’t see why a studio wouldn’t at least try to develop this.

Oh, and you can read the script yourself here!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Avoid “turn-based” dialogue. One of the tricks to keeping dialogue natural is to make sure the characters are listening to each other. That way, they’re responding to one another as opposed to saying what the writer wants them to say. I found a fair bit of turn-based dialogue here. For example, here’s an exchange…

FULLERTON

You’re seriously making the argument that an artificial intelligence has rights?

RANDU

While PRISM’s consciousness may in the strictest sense be artificial compared to our own, its evolution has advanced to the point that there’s no longer any meaningful dissimilarity between the two.

The character of Randu did not hear a single word the character of Fullerton just said. Instead, a very formal well-written answer – something you can tell was crafted and perfected ahead of time – was given instead. To fix this, put yourself in Randu’s shoes. LISTEN to what Fullerton is saying. The response, then, would probably be more reactive…

RANDU

Why wouldn’t it? While the system’s consciousness may be artificial, it’s advanced to the point where the similarities between the two are negligible.

Obviously, how you write the sentence itself will depend on character and your own voice. But the point is, you want dialogue to have that natural rhythm that comes with people listening, thinking, and responding. In real-life dialogue, you never have the perfect response waiting.