Search Results for: F word

Genre: Drama

Premise: When a struggling actor’s father is diagnosed with cancer, he must finally grow up and become the patriarch of his family.

About: This film received a lot of press when writer-director Zach Braff raised the funds for the film on Kickstarter. There was some initial backlash, as some noted that Braff would’ve been able to raise the money by traditional means anyway. But Braff argued that doing it the Kickstarter way enabled him to make “no sacrifices.” Which means, of course, that for better or worse, this is exactly the film Braff wanted you to see. Braff’s previous writer-director entry, Garden State, was a surprise hit at Sundance and went on to gross 10 times its budget. Everyone kept asking him, “When are you going to direct again?” Well, 10 years later and Braff’s second movie is finally here!

Writer: Adam J. Braff and Zach Braff

Details: 120 minutes

The Wish I Was Here experience can be summed up by its title. Many hours after I saw the film, I casually wondered, “Why didn’t he just call it ‘Wish You Were Here’ as opposed to this strange variation on the phrase?” Then I realized, “Ohhhhhh. The ‘I’ is a play off the phrase, implying he wishes he was currently present in his life.” I felt a little dumb for missing that, but upon further reflection I realized, “Wait a minute. That was kind of a clumsy play on words. By no means was it obvious.” Which pretty much summarizes the movie itself, a clumsy story that wasn’t easy to get.

The script starts off strong, with a traditional setup of goals, stakes, and urgency. Aiden (Braff) a struggling actor with an 8 year old son and 11 year old daughter, has been married to his wife since college. His kids go to a prestigious private Jewish school courtesy of Aidan’s rich father. But when his father gets cancer and must pay out of pocket, the checks to the school stop, and all of a sudden, Aiden’s free ride in life is over. For the first time ever, he must figure out a way to provide for his children, which means he must consider giving up his acting dream.

Goal = find a way to keep his kids out of public school. Urgency = the check to the school is due in a couple of weeks. Stakes = if he doesn’t figure it out, he might have to give up his dream.

Okay, I can get on board with that, even if the goal is a little “Rich People’s Problems.” But thennnnnnnn… the second act comes. Second acts are where screenwriters make their money. The professionals know how to write them. The posers fake their way through them. And there was never a second act more faked through than “Wish I Was Here.”

Structure is the tool that creates narrative. You make sure your characters are going after something, and that that something is clear and has consequences. That’s what pushes your characters forward, giving them things to do and actions to achieve. The second we stop understanding what your characters are going after and why, we lose interest.

Look at a movie like Raiders of the Lost Ark. What happens if, once we hit the second act, Indiana heads off to Iceland, buys a cottage, makes friends with the locals, and becomes a carrot farmer? You’d be confused, right? You’d say, “Wait, wasn’t he going to go after that Staff of Ra thing? Isn’t that what the beginning of the movie was about?”

Yet that’s exactly how Wish I Was Here unfolds (or should I say “unravels”). Once we’ve set up the goal (figure out how to keep the kids out of public school), we go through one tiny sequence of Aidan trying to home school his kids (which was silly – but at least he was pursuing the goal that was set up), and then that was it. The “keep the kids in private school” thing was forgotten.

Instead, we drifted from scene to scene focusing on characters discussing the complexities of life (from dying dad to recluse brother to frustrated wife to confused kids).

One particular scene embodied this problem. It occurred midway through the film when Aidan and his wife (played by Kate Hudson) are sitting alone on a Life Guard chair on the Santa Monica beach, at night, talking about how they used to be happy.

This is the kind of scene that you, as a screenwriter, should kill people to avoid. It is the definition of a “scene of death” (scenes of deaths are screenplay killers). It’s also common for amateur writers to misinterpret these scenes for “good writing.”

And why not? “Important” things are being discussed (life, love, regret!). But a discussion about these trite obvious life experiences never offers anything more than impatient seat-shifting. First, the scene is on the nose. Characters talking about their feelings is almost always boring unless it’s a climax scene where they’ve spent the entire movie holding back and are only now letting loose.

Second, two characters sitting down talking is almost always a bad idea. It’s the definition of stagnant so it almost always plays dead. Third, you never want characters talking about their backstory together unless said backstory reveals something surprising or adds something important to the story. Characters discussing things that we’ve already assumed, such as they were once happy (Of course you were once happy! You got married!) is never a recipe for a good scene.

But the worst part about this scene is that when you sit two characters down in a comfortable environment with nothing else going on and a seemingly endless amount of time at their leisure, you say to your audience, “There is nothing going on in my movie right now.” Because if there was something important going on in your movie, your characters would be dealing with it. They wouldn’t be out here droning on about when they first met.

Assuming that the point of this scene was to show that these two were once happy (which I still think is a pointless scene since we already know that), let’s compare it to a scene from American Beauty that is sort of trying to do the same thing.

In the scene, Lester (the main character) has just bought a 1970 Pontiac Firebird without telling his wife. She stumbles in to find Lester carelessly drinking beer on the couch and angrily demands to know whose car that is in their driveway. He tells her it’s his. “Where is the Camry?” she asks. “I traded it in.” After arguing a bit longer, Lester pulls Carolyn close, and all of a sudden, the mood is charged. Everything about the present is forgotten. They’re young again. They’re excited.

They descend onto the couch like teenagers when Carolyn notices that—“Lester. You’re going to spill beer on the couch.” And just like that, the moment is ruined. The two go back to jabbering before Carolyn eventually storms out of the room.

Notice how much more is HAPPENING in this scene than in the “Wish I Was Here” scene. It starts off with a problem, creating conflict from the outset. “Whose car is that in our driveway?” The scene then makes an unexpected turn in the middle, when Lester makes a move and the unthinkable happens – Carolyn is actually into it.

This part is important, because we’re seeing an action that shows us how they used to feel about each other. He’s not telling her, “Remember when we used to like each other?” We’re seeing it. Then the scene turns again when Carolyn lets her obsession about inconsequential things get the best of her and the moment is lost. So not only is there something happening in the scene, but we’re exploring character as well (Carolyn’s flaw of not being able to “let go”). How much more interesting is this than two people sitting next to each other like robots and saying, “Remember when we used to like each other, bee-beep booop?”

But but but! I want to play devil’s advocate here. If I were Zach Braff, I’d probably defend my script by saying, “Carson, you’re focusing too much on these tired “rules” of screenwriting that there has to be a “goal.” That the plot always has to be straightforward and easy to follow. My movie’s not like that. My movie is about characters and how they interact with one another, how they battle life’s complexities and problems. It’s not about having a clear A to B story.”

Okay, that’s a fair argument. There are successful movies that do this. And to a certain extent, I agree. If you have an interesting set of unresolved relationships in your script, then the “narrative,” (the thing that drives the reader to keep reading) is to see if and how these relationships are going to resolve themselves. That’s how When Harry Met Sally works. We stick around solely to see if they’re going to get together.

And Braff definitely puts a lot of effort into this area. Aidan’s dad doesn’t like how Aidan is an actor. Aidan’s dad doesn’t like Aidan’s brother for being such a dumbo. Aidan and Aiden’s brother don’t talk as much as Aidan wants them to. Aidan and his wife are struggling to find the love they once had. Aidan doesn’t agree with his kids’ infatuation with the Jewish culture.

I agree that, assuming we care about these relationships, that theoretically they can carry the script. But therein lies the problem. I didn’t care about the relationships. And it was mostly because of scenes like the one above. Instead of characters EXPERIENCING problems, they would often TALK about problems. And there isn’t a whole lot dramatically exciting about people talking about their problems. It goes back to the oldest screenwriting rule in the book. Don’t tell us. SHOW us. And there were too many “Character A sits across from Character B and talks about life” TELL scenes.

That’s why story is so important, why character problems aren’t enough. Story forces characters to act instead of sit around and talk. Which means characters are changing through action as opposed to conversation. The only action in Wish I Was Here were gimmicky scenes that had nothing to do with the story – like going out and test-driving a Maserati to feel better about themselves – empty visual experiences.

Wish I Was Here tries so hard to be that emotionally moving movie about life and death, but Braff doesn’t have the writing skills to pull it off. Too much talking, not enough happening.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware Peacock Dialogue. Braff has a nasty habit of drawing attention to his favorite lines of dialogue. He spotlights these moments by stopping all space and time so that YOU KNOW HE LOVES THIS LINE. These lines scream, “I want to be in a trailer!” and have that larger than life feel. These sound right at home in a trailer, but are too big and showy to work in the moment. “You can pick ANY ONE you want, as long as it’s unique and amazing… like you.” “When we were kids, my brother and I used to pretend that we were heroes, the only ones who could save the day. But maybe we’re just the regular people. The ones who get saved.” Dialogue should always serve the moment. If it becomes bigger than the moment, it’s a peacock (sprouting its feathers) and draws attention away from the scenery behind it.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre (from writer): Strip-com

Premise (from writer): Dodd and Ollie think they’ve hit the jackpot when they inherit a strip club, but they soon find out it just might be the worst place on Earth.

Why You Should Read (from writer): I notice you’ve been doing more TV stuff lately. Tina Fey’s sitcom and then the AOW of TV dramas. Maybe it’s time for an Sitcom amateur Friday? How can you resist? It’s one fourth the work of reading a screenplay! — Now that you’re completely sold on the idea, here’s why you should select my sitcom pilot. It’s an R-rated workplace comedy designed for pay-cable or the internet. My idea was to take the typical big, dumb network sitcom and give it a cable edge. Imagine something like “Cheers” with drugs and nudity. It’s in the vein of some of my influences: Peep Show, Eastbound and Down, and It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia.

Writer: Colin O’Brien

Details: 36 pages

A couple of weeks ago we switched up the Amateur Offerings procedure to reflect the state of entertainment as we know it. Instead of being script racist and separating the pilots from the features, we offered a conglomerate of ALL screenplays, movies AND television for your voting pleasure.

Not surprisingly, the vote came down to a feature (“No Guts No Glory”) and a pilot (“NSFW”). The vote was so close, I decided to read the first ten pages of each to determine which got the review. Since they were both comedies, I based my decision on laughs. Humor is entirely subjective, but I could only smile during the first 10 pages of No Guts No Glory. With NSFW, I laughed half a dozen times. So NSFW it is!

Children’s book publisher and all around conservative guy, Benjamin Dodd, is attending his creepy uncle’s funeral with his wacky best friend, Ollie, where he learns that Uncle Chester left him his infamous strip club, SKANKS.

Ollie thinks this is a sign from God (what that sign is isn’t clear) whereas Dodd treats it as an annoyance. His plan is to sell it right away. But Ollie convinces him to go check it out first. How can they sell something without getting to know it?

Over to Skanks they go, where they conveniently learn that there’s some strange rule in the contract that they’re not allowed to sell the place until it’s profitable (wha??). So all of a sudden, Dodd’s stuck as the official owner of a strip club!!

The two start meeting all the strippers (like the cute Sizzlean, who’s the world’s worst stripper. Every time she tries to talk dirty, she inadvertently lets slip that she’s only doing this for the money), Roxbury (an out-of-shape 50 year old whose big move is ashing her cigarette while she’s grinding you) and Jasmine (Ollie’s ex-girlfriend who’s become a stripper to get back at him).

In the end, Dodd becomes smitten with Sizzlean, and figures, what’s the harm in running this place until he can sell it? Let the adventures of a children’s book publisher turned strip club owner begin!

Now before I get started on my thoughts here, I want to explain why I chose this over No Guts No Glory. Gazrow is a great longtime contributor to the site and I want to help him out with a little feedback.

Upon reading the first few pages of “Guts,” I felt an intense similarity to Zombieland, with the backstory voice over that eventually leads us to the present day where we meet our zombies. When you write something similar to a famous movie, you create two problems for yourself. 1) It makes you look unoriginal. As soon as people go, “This is just like Zombieland,” they lose confidence that you’ll be able to deliver something fresh and exciting. 2) You invite quality comparisons to that film, which, 99% of the time, you lose. The stuff about being scared ever since he was a kid was kind of charming. I smiled. But it wasn’t as creative or funny as the whole “zombie survival rules” voice over in Zombieland. Zombieland set up an exciting new world. The voice over here felt more expository.

My official check-out point, though, was the Neo-Nazi Hitler-loving step-dad. Now I have no problem with Hitler or Nazi jokes. They can be hilarious in the right context. But it always worries me when one of the big early jokes in a script is NOT CONCEPT-BASED. In other words, if you were writing “Neighbors,” and one of the first jokes involved a character with a flesh-eating virus, I would be worried. What does that have to do with a family who moves next to fraternity house? Why aren’t you getting your jokes from that situation? That’s why we paid to see the movie.

Now I’m not saying this Nazi father thing doesn’t somehow link up to the zombie stuff later on, but as a reader, these are the mental “flags” that can quickly pull us out of a script. The huge left turn into Nazi humor was too jarring and too broad, and ultimately what led me to go with NSFW. It should be noted, however, that comedy is entirely subjective. And for some people this might’ve been fine. Still, I always think that when you pick a comedy idea, almost all the jokes should stem from the concept.

Back to NSFW. This script started out strong. I love that it didn’t feel like the writer was trying too hard to be funny. The laughs were just happening. I liked that we jumped right into the story as well, with some scary biker dude eulogizing Uncle Chester with the most inappropriate story ever. Good stuff.

From there on, though, it was a mixed bag (as comedy often is). I found Ollie to be a little on-the-nose. Like “Look, I’m the wacky friend! Look at how wacky I can be!” When you create the wacky sidekick character, it’s important to give him a fresh spin so he doesn’t feel like every other comedy sidekick ever. It’s usually about finding an angle (a “lives with his parents” socially unaware entitled brat – Alan from The Hangover). If your only synopsis for a character is “the wacky friend,” you’re in trouble.

From there, we need more story and more drama. Let’s take a detailed look at how to do that.

DODD

We need to know more about Dodd and his job BEFORE he inherits the strip club. You want to create the maximum reactive impact from a children’s book publisher being given a strip club. That doesn’t happen here since I didn’t even know he was a children’s book publisher until AFTER he inherited the strip club. So find a way to squeeze this in early. Maybe in the opening funeral scene, we see Dodd leafing through a number of children’s books. There can be mothers nearby who spot him doing this and mistake him for a pedophile. Also, I’m not sure you want to leave this scene without Dodd going onstage and saying something about his Uncle. It’s a chance for you to tell us a little about Dodd. Why not take it?

THE STAKES

It’s not clear why Dodd needs to manage this place. There’s a vague allusion to some artificial “condition” in the deed that he can’t sell Skanks until it’s profitable. That’s weak sauce. Let’s build a real reason why he needs this place and add stakes to it. For one, maybe there’s something Dodd needs (a new house – I’ll get to why in a second). Whereas he barely makes anything at his publishing job, he finds out this place is a goldmine. This is his meal ticket to a comfortable life. If you don’t like this idea, you allude, in the story, to some gangster the old manager owes a lot of money to. When Dodd takes ownership of this place, that debt is now transferred over to him. It could be 100 grand. So Dodd HAS to run this place to make enough money to pay this psycho gangster off or else he’ll be killed.

A FIANCE

I think you’re missing a huge opportunity by not giving Dodd a fiancé here. You can have his fiancé be a controlling bitch as well as out of his league. She’s super conservative, as is her wealthy family. Now, by accepting ownership of this strip club, you’re creating a world of conflict at home with his fiancé. Also, with his fiancé being the breadwinner, Dodd has always felt emasculated. For once, he wants to be the breadwinner (and buy an expensive ring or a house for the two of them) so that she’ll finally respect him. He takes this job to do just that. You can play this two ways. She finds out about Skanks, which creates all sorts of conflict within their relationship, or he hides it from her, which can be funny in other ways. Also, this creates a lot more romantic chemistry between Dodd and Sizzlean, since we know they can’t be together. The fact that neither of them are taken right now makes their potential romance unexciting. That’s easily changed by giving one of them a significant other.

YOU CAN GET MORE OUT OF THE WORK STORYINE

Once they get to the strip club, everything is too easy. They’re able to hang out there, explore, get to know people. It’s kind of funny, but without any conflict, it’s not nearly as funny as it could be. Conflict is your best friend in comedy. You need something bigger PULLING at Dodd here, so his time at the strip club is never comfortable. Now that we’ve introduced a fiancé, she can always be calling and telling him to “get over here” (maybe she’s even his boss or an upper level employee at the publishing house he works at). That gangster can show up and demand his money. Finally add an immediate problem from the company itself that’s demanding his attention. We can’t ever feel too comfortable in a comedy, that things are going to be okay. This setup feels too comfortable.

Because of some of these structural issues, I can’t quite give this a “worth the read,” but it was close. As you can tell from how in-depth I went, I believe in Colin. Just remember, it’s not all about the funny dialogue. You have to continually put your characters in bad situations to find the best comedy.

Good luck!

Script link: NSFW

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Finally! A writer who gets this right! One of the most ANNOYING things a reader endures is the ambiguity in which a writer picks a character’s first or last name to deliver dialogue. For example, one character will be introduced as SOLOMON HASHER and another as RYAN SMITHSON. Then, when it’s time for dialogue, one of those characters will be known as ‘HASHER’ while the other is “RYAN.” Why the last name of one but the first name of the other????? What Colin does is he introduces Dodd as: “Benjamin DODD.” And then Ollie as simply, “OLLIE.” By only capitalizing Dodd’s last name in the intro, it makes sense why his last name is used for dialogue, while with Ollie, his first. I think this is the first time I’ve ever seen this. And I thank you, Colin. I thank you!

Mistake #15 – Too many characters!

Mistake #15 – Too many characters!

After consulting on a script last week, the writer asked me, “Is there anything in my script that screams amateur?” I found that to be an interesting question. As writers, avoiding that amateur status is a must. No one wants to cluelessly show up to their first hockey practice wearing a football helmet. Now the truth is, the best way to shake off all the amateur mistakes is through good old fashioned practice. But we at Scriptshadow are committed to speeding that process up.

So today, I’m going to list the top 21 amateur mistakes I encounter. If I see any of these in a script, I know I’m dealing with an amateur. But instead of listing them for you in order of frequency, I’m going to list them in order of importance. So the number 1 mistake is the absolute WORST amateur mistake you can make. The number 2 mistake, the second worst, etc., etc. Oh, and because I love you guys so much, I’m going to give you 21 little mini-solutions to these mistakes. Are we ready? Let’s do it.

1) Bad Concept – Boring, uninspired, and drama-less movie ideas are the most crippling mistake you can make as an amateur. Your script is dead before the reader has even made it to the first word of your screenplay.

Solution – Always field test your ideas. Go off the energy of the reaction rather than the words. If someone looks and sounds excited after you give them the logline, it’s a good idea. If someone acts reserved, confused or polite, it probably means they don’t like the idea, even if they say they do. Of course, get different opinions. No idea is universally loved.

2) Passive/Reactive Protagonist – If your hero is not actively pursuing something in your script, that means he’s sitting around waiting for things to happen, which means your story is probably waiting around too. There are some movies that don’t have big goals driving the story, but they’re often niche material and they’re often not very good.

Solution – Make sure your hero always has a goal at every point in the story. If they achieve one goal, give them another.

3) Cliché – Everything from the characters to the scenes to the plot points are stuff we’ve already seen in other movies.

Solution – Stop using choices you’ve seen from other movies. If you’ve seen one of your characters in another movie, change him. If you’ve seen a scene before in another movie, don’t use it. You won’t always succeed, but you should at least try to come up with a fresh take on every choice you make.

4) Lack of effort – Nothing seems very well thought through. Scenes feel empty and rushed. Even character names seem flat (Bob, Joe, Bill). You get the sense that the script was written in a week with the writer never once questioning any of his choices.

Solution – If you want to compete in the big-leagues, you have to bring your A-game. Think through as much of your story as possible before you write it. And always question your choices while you’re writing it. Ask yourself, “Can I write a better scene here?” If the answer is yes, re-write the scene.

5) Thin characters – None of your characters has any depth. They lack flaws, backstory, a compelling worldview, anything interesting to say, or any sense that they existed before they first appeared in your script.

Solution – They’re annoying as hell, but write a 3000-5000 word backstory for all your major characters detailing their life from birth until present day. The more you know about someone, the more real they’ll appear on the page. Also, every person on earth has one major flaw holding them back (even you!). Figure out that flaw in your characters, and make sure it keeps getting in their way throughout the story (if your hero is selfish, keep giving him opportunities to be selfless).

6) No drama – There’s very little conflict, obstacles, or choices that anyone in your story has to deal with. Things are handed to your hero without him having to work for it. Scenes often consist of agreeable characters talking agreeably.

Solution – Start every scene with an imbalance. Someone wants something and the other person doesn’t want to give it to them. That’s not the all-encompassing answer to creating drama, but it’s a start.

7) Unnecessary scenes – Amateurs love to include scenes that have nothing to do with the story. They figure as long as their characters are talking about something, it’ll be “entertaining.”

Solution – Figure out what your hero’s main goal is (defeat the terrorists). If you’re writing a scene that isn’t necessary to your hero achieving that goal, it’s probably not necessary.

8) Slow first act – A close cousin to the above, writers use two, three, even four times the amount of scenes they need to set everything up. They think they’re “adding depth” by building up their world, when in reality, they’re boring the reader, who’s getting impatient because nothing’s happening.

Solution: Things always need to happen faster in your story than you think they do. Move that exciting plot point from page 30 to page 15. Move your big midpoint twist from page 60 to page 45. Get to the good parts sooner, then create more good parts. You’ll thank me.

9) On-the-nose dialogue – Characters say exactly what they’re thinking all the time, leading to predictable and boring dialogue.

Solution: In general, people hide their true thoughts behind facades. The happiest person is sometimes the saddest on the inside. The person who’s the nicest to you may be the one always talking behind your back, or seeking something from you. Always remember that when you write dialogue. There’s usually a hidden agenda.

10) No stakes – Nothing really matters in your story. Your characters will end up in relatively the same position whether they succeed or fail.

Solution – Make sure there’s always something on the line for every character in the screenplay, not just in the overall story, but in each individual scene. The more that’s on the line, the more intense your story or your scene will be.

11) Telling instead of showing – Given the choice between telling the reader something, (“Hey Joe, I heard you’re the best realtor in the state,”) or showing them (a scene where Joe convinces a family hell-bent on not buying a house to buy it) the writer almost universally chooses to tell it. Hence, their script is full of talking heads instead of action.

Solution – This one’s easy. Every time you need to tell the audience something important about your plot or your characters, you’re not allowed to let your characters say it. You have to come up with a way to show it through action instead. Finding the right “show” scene is one of the most rewarding feelings in screenwriting.

12) Lack of clarity – This is one of the hardest ones for an amateur writer to catch because it’s completely beyond their realm of understanding. They don’t yet know how much information to give the reader, so usually border on too little. So the reader’s always confused about what’s going on. These scripts can be mind-numbing to read.

Solution – It’s a bitch finding someone who will do this, but the only way to really nip this in the bud is to have a “clarity” reader, someone who reads your script for clarity issues. After they’re finished, quiz them on all the major plot points and characters. See if they understood everything. If they didn’t, find out why.

13) A wandering second act – Everything seems to be going well at first, but as soon as the writer hits the second act, the script falls off the rails and becomes an unfocused mess.

Solution – Remember, character goals are your friends. As long as your protagonist is going after something important, your script will have direction. The second he isn’t, your script is going to lose steam. Once again, if a goal is met, replace it with another one, preferably one bigger than the last.

14) No urgency – Nobody seems to be in a hurry to do anything. While not as crippling to a screenplay as no goal or no stakes, a script without urgency starts to feel slow and unimportant.

Solution – Even in an indie film, the idea is to always have something your characters are trying to do, and preferably something they need to do quickly. “Quickly” can be relative, but in general, it should feel like your characters are running out of time to do whatever it is they’re trying to do.

15) Over-description – The reason why you see a lot of over-description (“The cool grass nuzzles up against packed dirt as a hulking boot plunges down on the oxygen-dependent blades”) is a) because most new screenwriters write as novel-readers, since that’s the only kind of writing they’ve read up until this point and b) because they want to impress you with how many words they know. Neither is a good thing.

Solution – During important moments (an important character, an important location, an intense scene) that’s when your description should be a little more colorful. Otherwise, keep it simple and clear. It’s a screenplay and meant to be read fast.

16) Too many characters – The writer just keeps introducing them. Every new scene has another character or two. And they actually expect the reader to remember all of them!

Solution: Ultimately, your story will determine the number of characters you include. I read a script last week with 4 characters. I read a script yesterday with 15. Just remember that you usually don’t need as many characters as you think you do. Try to combine or cut characters if possible. Use the extra script time you gain to develop your main characters. If you have over 20 named characters, you probably have too many.

17) Plot is unnecessarily complicated – Amateurs love to make things way more complicated than they need to be. Lots of plot twists. Triple-agents. The guy who works for the secret guy who works for the secreter guy. Complex plots are actually great when done well, but the amateur doesn’t yet know how to navigate these tricky waters. They’re still learning. So it’s a little like watching a 4 year old try to skate an Olympic freestyle routine. Sure, you’re really rooting for them. But after they’ve fallen down five times in a minute, you don’t want to watch anymore.

Solution – Your plot will be determined by your story. Chinatown is going to have more plot than Paul Blart: Mall Cop. But in general, your plot should be simple. Any complexity should be saved for your characters.

18) Terrible use of exposition – Characters talk endlessly about the plot and each other’s backstory, and there’s no attempt to hide this exposition at all.

Solution – However much exposition you think the audience needs, divide that by four. That’s how much you’re allowed to give them. Therefore, find the 25% of your exposition you believe is the most important, and hide it throughout your script in parts.

19) On the nose characters – This usually goes hand-in-hand with on-the-nose dialogue. This includes characters who act and talk exactly how they look. A big muscly guy who has a big burly Brooklyn accent. A small nerdy guy who loves computers. The hot girl is, of course, a bitch. The old hag who lives next door is a giant meanie.

Solution – A form of on-the-nose characters can be okay (by “a form” I mean still adding a twist to them. A meathead can still talk like a meathead, but maybe has some unexpected trait, like he loves cats). But mix in these on-the-nose characters with off-the-nose ones as well. The nerd who’s a stud with the ladies. The basketball star who’s a quiet recluse. The company CEO who’s a jokester. This is one of the easiest ways for me to spot a writer who knows what they’re doing, the ones who create off-the-nose characters.

20) Way too much mindless action – Amateur writers often mistake “something happening” for “lots of action.” But if we don’t know why the action’s happening or know the characters who are in the action well, we won’t care. Check your favorite action movies. Write down the ratio of scenes with action to those without action. You might be surprised at how many non-action scenes there are.

Solution – Put more emphasis on character development instead (putting your hero in situations where his flaw is challenged. So if your character is anti-social, make it so he has to go to a party). That way, when we get to the action scenes, we’ll care more, since we’ll know your characters better and care whether they survive.

21) Spelling/grammar – You might be surprised that this one is so low on the list. But I’d rather have all the things above than good spelling. With that said, bad spelling and bad grammar usually go hand in hand with everything else here. Once people start taking all that other stuff seriously, they take more pride in their presentation.

Solution – Get a proofreader. Either here with us, with someone else, with your friends, family, whoever. But if you want to be taken seriously, your work has to look professional.

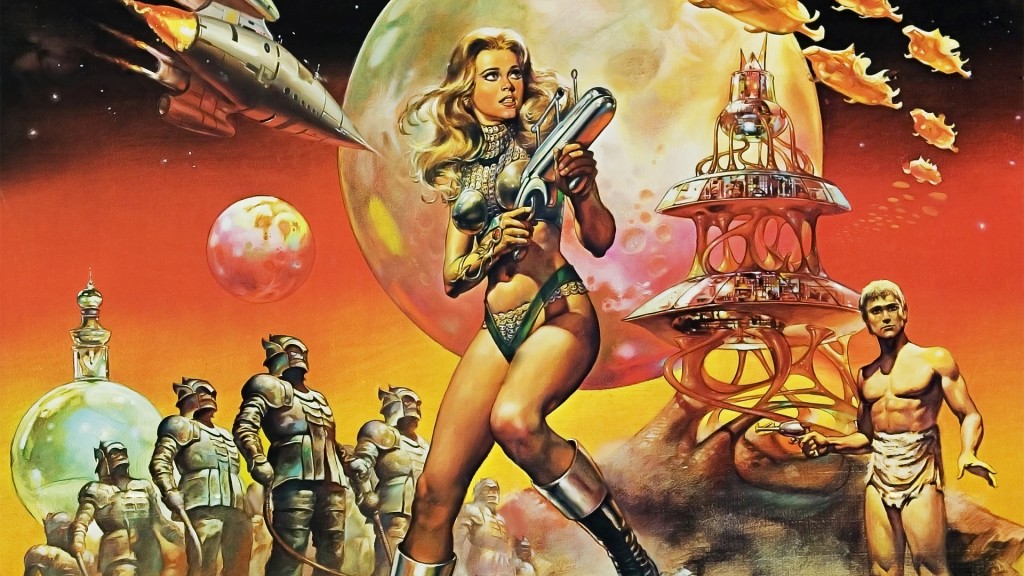

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: In a universe where men are dying off, a sexy star-cruising bounty hunter named Barbarella finds herself caught up in a plan to save them.

About: The original Barbarella movie, made in 1968, was a critical failure. But a lot of good things came out of it. The costume design had an iconic look to it that would later inspire many artists (including Jean-Paul Gaulteir on The Fifth Element). It also had one of the best posters of all time. It even started Jane Fonda’s career! (okay, it’s debatable whether that was a good thing) They’ve been trying to remake this film FOR-EVER. It got close a few years ago when Robert Rodriguez was planning to direct it. But his insistence on using unproven actress Rose McGowan in the tittle role scared the studio and ultimately killed the project. This version of the script was written by long-time James Bond screenwriters Neal Purvis and Robert Wade (who are also writing Bond 24). Will we ever see a Barbarella remake? I don’t know. But for some reason, I feel like with Nicolas Winding Refn looking to move into bigger movies, this would be perfect for him. They’re both weird and offbeat. Seems like a match made in Refn. Nicolas? Are you out there?

Writers: Neal Purvis and Robert Wade (based on the French comics by Jean-Claude Forest and Claude Brule and the 1968 screenplay by Terry Southern and Roger Vadim).

Details: 89 pages – 2007 draft (alternate ending version)

Barbarella redefined movies.

Okay, even I couldn’t type that with a straight face.

Barbarella’s biggest achievement was that if you came across it on cable, you usually didn’t change the channel. That was for a number of reasons, mainly that Jane Fonda’s outfit allowed you to see her breasts, which was pretty stellar if you were a little boy.

But even without the world’s first deliberate wardrobe malfunction, the movie had a goofy charm to it. Something about it worked, even though the filmmakers themselves would be hard-pressed to point out what that was.

Naturally, with this being Hollywood, they’ve been busting their ass trying to get this back up in theaters. But the Movie Angels have not shined down on the producers, partly because it’s obscure and partly because it objectifies women, something you could get away with back in the 60s, but is a lot harder to do now.

But you can’t fault them for trying. They brought in some heavy hitters to write this draft (the Bond guys) which must have cost them a pretty penny. And I guess it makes sense. Bond uses his sex appeal to smooth-talk his way out of problems. Barbarella uses her sex-appeal to get out of tough spots. Maybe this will work?

Barbarella, our sexy bounty hunter, has just received some bad news. Her evil nemesis, the one-eyed Severin, has escaped from Planet Hulk prison with plans on killing the woman who put her there (that would be Barbarella).

That’s a hefty to-do list for even the strongest heroine, but Barbarella’s ALSO received word that she must travel to the Black Moon to save a king. These orders come from three motley dudes who call themselves The Watchers, who are the last of their kind in the galaxy.

The new boys in town are the “Baal,” an evil race of aliens who now number in the trillions. They’re also trying to find the elusive King, since if they kill him, they can increase their population by… I don’t know, I guess another trillion? (Thinking too deeply about logic in this script is highly discouraged).

Along the way, Barbarella meets a sexy alien named Rael, who only has a 12 year lifespan because someone thought that was a cool idea. But Rael joins her and the two jet off to the Dark Moon, where they find a bunch of men hiding underground, eager to repopulate the galaxy.

Oh yeah, I guess the galaxy is light on men or something? That’s sort of thrown in there towards the end. But yeah, Barbarella finds the king, shuttles him and all his buddies to a planet of Amazonian Jungle women, and the reboot of mankind begins. Yay.

Before we even get to the “story” here, I need to point out that this script used really tight margins and big letters. Which means it’s even shorter than its 90 pages suggests. I’d say its true length is 80 pages. Which means this read should’ve FLOWN by. Yet never has a script read so slow. I had been reading so long, I thought I was almost done with this monstrosity. I was POSITIVE I was at least on page 70. I checked the page number. 33!!! I wanted to kill life.

What was wrong with this script? What wasn’t?

Let’s start with the simple. If you’re going to write a comedy science fiction or comedy fantasy, keep the universe and the plot simple! We’re here to have a good time and laugh. Why would you impede that by building an overly complicated universe with 10 different planets and Watchers and Baals and aliens who only live to 12 for no story reason whatsoever??

I lost interest in this screenplay so quickly because all my energy was focused on figuring out what the hell was going on. Barbarella is secretly the daughter of the King of the Dark Moon, sent here by the Watchers who had actually been tricked by the Baal to lead Barbarella to the Dark Moon King so they could trap him and take over a universe they already own??? I DON’T CARE!

I mean, if you’re writing a Game of Thrones or Dune adaption, dramas where the intricate plots and relationships and backstory are essential to enjoying the story, then a more complicated storyline is understandable. But this is a movie where a woman has replaced one of her nipples with an eyeball!

Whenever you’re brought in to write a remake, one of the things you have to decide is how you’re going to update the material. Are you going to keep the tone the same, or are you going to change it? Make it more current? The further back the original material goes, the more likely it is that you’ll have to update it. I mean a lot has changed since 1968, hasn’t it?

For one, you can’t exploit women onscreen anymore. And whereas we used to forgive our mainstream films for looking cheap and silly (it was part of their charm), these days, the audience requires more of a grounded believable experience (relative to what the movie is). Even Transformers, for how gloriously bad it is, has a strong visual world.

Barbarella feels like it still wants to exist on cheap sets and use bad special effects, like that remake of Escape to New York. Remember how that worked out?

The thing is, it’s got some cool elements to work with. A sexy star-hopping bounty hunter heroine. A badass female nemesis. Why not ditch the midnight-movie angle and build something more grounded in reality? I mean even the affable Clark Kent doesn’t smile these days. It’s not like you’re going to piss off the 7 members of the Barbarella fan base.

And for the Jesus in all of us – people! Stop over-complicating your plots and your worlds when there’s no reason to. If you’re writing Chinatown, yeah, create 10,000 layers of deceit. But if you’re adapting Bob’s Burgers, we don’t need to find out that Bob’s great-grandfather was leader of the CIA and had a daughter who now works for the Russians who’s married to the sister of Fred’s Fries. Stop already!

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When writing sci-fi, use easy-to-remember names for things like planets, characters, cities, etc. The reader’s forced to remember so much in sci-fi/fantasy, that you have to lighten the memory load for them where you can. You do this by giving people/things names that sound similar to who/what they are. For example, if I named an alien “Occarius,” and didn’t mention him for ten pages, you may not remember him when I brought him back (“Wait, who is Occarius again? Is that Jozzabull’s brother?”). But if I named him “Darth Vader,” that’s a name that’s easy to remember (“Darth” sounds very much like “Dark,” which implies a “bad” person). Ditto the “Death Star.” You know what that is every time I bring it up. I’m not sure that would’ve been the case had I called it “Pomjaria.” Now these choices are always relative to the tone and the story you’re telling. If you’re writing really serious sci-fi, the “Death Star” may sound too much like a B-movie. But the spirit of this tip should remain the same. Any way you can you pick a name that helps the reader remember that thing, do it.

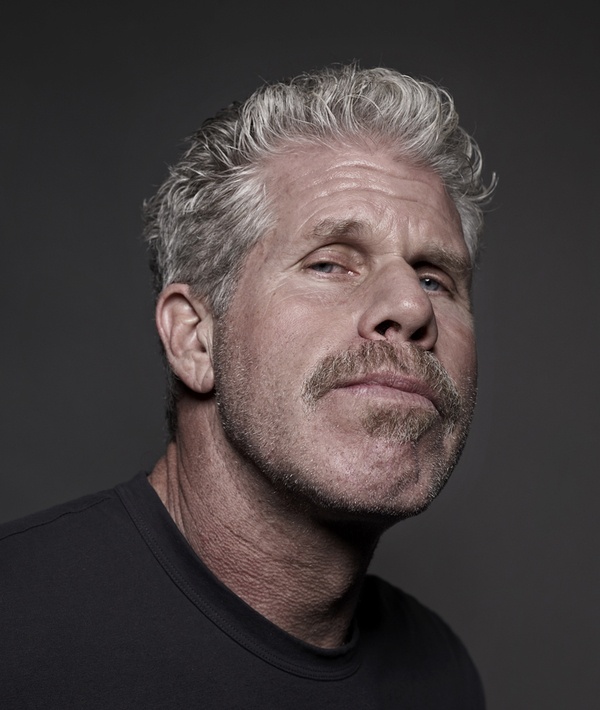

Genre: TV Pilot (Drama)

Premise: After tragedy sends a local judge into a spiritual awakening, he starts making judgements based on faith over fact.

About: Amazon is tired of being left out of the TV discussion so they’ve decided to come hard to the table. “Hand of God” will star everyone’s favorite character actor, Ron Perlman, and have super-helmer Mark Forster (World War Z, Quantum of Solace) directing the pilot. The cool thing about these big TV pilots is that they’re written by “nobodies,” so every time we read one, we get to experience a new voice. “Hand of God” was written by Ben Watkins, whose only work up to this point has been on the show, Burn Notice. Recently, Ben was asked what the most difficult challenge was about this business. He answered, “This business is built on one ridiculous challenge after another. In my opinion, there’s only one condition that is fatal – losing faith in yourself.”

Writer: Ben Watkins

Details: 68 pages

I’m not going to mince any words here. I’m pissed this is going to Amazon. Because if it’s on Amazon, no one’s going to see it. And this is too good of a show (or pilot) not to be seen. I mean honestly, how do you watch a show on Amazon? I go to Amazon and I see 10 billion different links. I’m lucky if I can find the electronics section.

I get that Amazon wants to rule the world but the reason Netflix is so dominant in this space is that you know what it is when you go to it. I want to watch something. Click. Netflix. With Amazon, you have to jump through 18 dozen hoops. Combined with the fact that most people don’t know that Amazon even offers TV shows, and I’m not sure how Hand of God is going to get any attention.

It won’t always be like this. I can see a future (maybe 10 years from now) where TV and cable are dead. Everything will be on demand and a la cart via services like Netflix and Amazon. But we’re not there yet. Which means Hand of God might go down as the best show nobody’s ever seen.

We find 50-something Judge, Pernell Nathaniel Harris, in a park, naked, speaking in tongues. Nobody’s seen him for days and this is how he decides to reintroduce himself. Pernell has a pretty good excuse, though. His son shot himself a few days ago and is brain dead on life support.

As the mayor, attorney general and police chief all try to delicately bring Pernell back to the land of the sane, they realize this religious awakening he’s had isn’t going away. Pernell has pledged his loyalty to a con-artist wacko priest who claims to have a direct line to God – to the tune of a 50 thousand dollar endorsement check.

In the meantime, we learn that the reason Pernell’s son tried to off himself is because seven months ago, he was forced to watch his wife get raped. Although he tried his hardest, he couldn’t live with the fact that he didn’t do more to try and stop it, so a bullet to the cranium seemed like a pleasant way out. Pernell is now on a mission to find the rapist and make him pay for what he did to his step-daughter and son.

The problem is, Pernell’s kind of crazy now. And instead of listening to logic, he’s listening to “God.” Voices and signs have taken precedence over testimony and facts. So when a religious sign points to a random member of the police department as the rapist, the authorities have to stop Pernell from taking the man down. But it’s too late for that. If Pernell has his way, he’s going to make sure Officer Rapist meets his maker, whether he’s proven guilty or not.

Wow.

I think this is my favorite pilot I’ve ever read. Tyrant was good, but this is REALLY good. Speaking of Tyrant, I don’t know what happened to that show. They took a gritty show about 3rd World dictators and tried to turn it into an 8 o’clock NBC family drama. Parenthood 2. Ugh, I’m still smarting from that. But Hand of God is getting me back on track. For a lot of reasons.

First of all, Watkins got the NUMBER ONE thing right when writing a pilot. He wrote a great meaty main character! How ironic is it that a man whose job is based on listening to facts, is making his decisions based purely on faith? Add in a healthy dose of crazy, the fact that he’ll hire hit men to get the job done, and you’ve planted the seeds for one hell of a harvest.

But as we know, every harvest needs rain. And Hand of God’s got plenty of that too.

The opening 10 pages are crucial for ANY script, pilot or feature. And they usually fall into three categories.

1) Nothing interesting happens in the first ten pages at all; I’m miserable that I have to spend the next 2 hours with this thing.

2) One or two interesting things happen in the first 10 pages, enough to pique my interest. I read on with desperate hope.

3) Every single one of the first ten pages is good, in which case, I know the script’s going to be awesome.

Number 3 is a rarity but that’s where Hand of God falls. We start off with this bizarre mystery. A man is naked in a park speaking tongues to the sky. At the end of the scene, we find out he’s a judge. Hmm, how did he get here, we ask? We’re intrigued. We then move to a hospital where a devastated beautiful woman tries to keep him from seeing someone named “PJ?” Who’s PJ. Ahh! We learn he’s Pernell’s son. And he’s in a coma. Why is he in a coma?? What happened? I need to know more!

In other words, there’s a lot going on in the first 10! Usually, amateurs will bumble along in their first 10 pages setting up the characters well, but in boring ways. They don’t have their heroes in parks, naked, speaking in tongues.

I also thought the whole “botched sucide” storyline was a great choice, and I’ll tell you why. 99 out of 100 writers, in order to motivate our hero, would’ve given Pernell a daughter and killed her off. Someone raped and killed her, now he’s out for justice. It would’ve worked, but it WOULD’VE BEEN BORING. Because we’ve fucking seen it before! The quickest way to disappoint a reader is to open the gates to The Kingdom of Safe and Predictable Choices.

The “watched rape/botched suicide” setup poses a more interesting set of questions. There’s not only a rapist on the loose we need to find. But there’s also the question of whether PJ’s wife is going to pull the plug on Pernell’s son or not. A big deal because Pernell, who’s riding dirty on Miracle Lane, now believes PJ will live. But he doesn’t have a say in this decision. And since she doesn’t want to see her husband suffer anymore, she calls to pull the plug. Interesting choices always lead to more interesting choices. Boring choices lead to… well, you get what I’m saying.

Then there were little things that shined like characters playing against the obvious in a scene. When Pernell’s wife goes to threaten Reverend Paul to stay away from her husband, she plays the whole scene calmly and with a smile. Her threats were veiled and implied. A lesser writer would’ve written this more on-the-nose, with the wife coming in and angrily warning Paul to “stay away from my husband!”

We even get some classic urgency (ticking time bomb style) to the pilot, with Pernell’s daughter moving quickly to pull the plug on her husband (in two days!). Pernell’s got to figure out a way to keep him alive, as he believes God will perform that miracle. But he can’t perform a miracle once the plug is pulled.

But what tipped this into the impressive category was the ending. The ending is almost always responsible for whether a script makes the “impressive” list. You can kick ass for 60 pages, but if you suck for the last five, nobody cares. Hand of God gets really good when one of Pernell’s religious visions points the noose at a random man who couldn’t possibly have committed the crime.

Not only are we wondering if he’s going to kill this man, vigilante style, but we’re fascinated by the question of: What if he’s right? I mean what if this totally random man really did commit the crime? What does that mean moving forward? Could Pernell truly be channeling God?

This was a wonderful pilot. Now, if only Amazon can figure out how to show it to people. That would be great! Oh, and since Amazon Studios is all about posting and getting feedback of their projects, I’m including a link to the script. Enjoy!

Screenplay link: Hand of God

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Never set foot in The Kingdom of Safe and Predictable Choices. It’s a land littered with 7-11s, McDonald’s and Supercuts. It’s comfortable. But it’s never inspiring. Aim instead for Paris in spring time.