Search Results for: F word

Genre: TV Pilot (Fantasy)

Premise: In a distant post-apocalyptic future, a young man in a mountain community begins to wonder what life is like outside his closed-off world.

About: Not much is known about this one other than AMC has shot the pilot and, presumably, will bury him this weekend. It’s being produced by Ridley Scott, which is a great sign, and written by long-time TV writer Jason Cahill. Cahill’s worked on a lot of big shows, including E.R., The Sopranos, Fringe, and AMC’s newest hopeful, Halt and Catch Fire.

Writer: Jason Cahill

Details: 54 pages – 3rd Draft (September 27, 2013)

Fast-rising actor Alex Russell will play Aethys’ best friend and rival, Roman.

Fast-rising actor Alex Russell will play Aethys’ best friend and rival, Roman.

Miss Scriptshadow and I have finally bit the bullet and started watching Game of Thrones. We realized our failure to get past five episodes in our last attempt had to do with us trying to “surf and watch.” Game of Thrones isn’t a “surf and watch” show. You have to be paying 100% attention 100% of the time or you very well may miss that Feargor is Tybo’s cousin, married to Calgo, whose dead wife, Sheeba, was a Tragdorian, and who’s brother Lingnotro is the secret heir to the throne of Six Whistles. If you don’t know that, it’s impossible to appreciate the show. And thusly, we’ve had no choice but to become hardcore viewers.

This segues idyllically into today’s pilot because, just like Thrones, there’s an extensive mythology and a lot of weird names and family connections to keep track of. We even have a giant page of character breakdowns before the script begins. Indeed, there’s quite the burden of investment required to enjoy Galyntine, but if you keep your sneakers on and fight through the thick bush, you eventually come upon a beautiful view.

Welcome to Mount Galyn, where a “large” community of 500 residents resides. The year? Who the hell knows? But we get the feeling it’s far enough out from the 21st century that little of that world remains.

The people of Mount Galyn are all about living off the land. You know those annoying cis-vegans that make you feel bad for even looking at a cheeseburger? These folks make them look like dog-butchers. They pick berries, they pick leaves, they hunt. But that’s it. You’ll never find the Galyns farming or processing anything. These are simple people who stick to a strict lifestyle.

Enter 23 year old Aethys, who’d had a rough life. As in something chopped off his arm when he was a kid. You’re not too desirable to the ladies if you can’t hunt. And so Stumpy must watch everyone else have the fun while he wonders if there’s a better life out beyond the mountains.

Aethys’ best friend, Roman, is his polar opposite. He’s big, strong, handsome, and routinely brings back the biggest elk. Their alliance is an unlikely one, but they’re both outsiders in their own way (Roman was an orphan).

The one thing besides Roman that keeps Aethys going is Wylie, his forever crush. And despite not being able to Facebook flirt in this world, it’s looking like he might actually get her. Maybe good guys DO finish first. Pfft. Yeah right! When Roman is shockingly rejected by Aethys’ sister, Essyn, Roman surprises everyone and takes Wylie instead! Ouch, talk about putting a damper on a bromance. Wylie the hell did he have to do that?

That’s the last straw for Aethys, who finally decides to get off this mountain. But even his first steps into this foreign land are met with shock. Something is down there. Something big and complicated and advanced. Maybe Aethys didn’t think this all the way through. But before he knows it, it’s too late. The new world makes its first bold move, changing Aethys forever.

Sometimes you read things where you know right away, “This writer knows what he’s doing.” There are people out there who will say that’s not true, that everything’s arbitrary. “One guy will hate your script and another will love it,” they argue. That’s not true. There’s a bunch of gunk filling up the Hollywood sewers that everyone can agree is terrible, stuff written by people who don’t know the craft. Only after that do you get to the arbitrary choice level.

Galyntine is the perfect example of a “some will love it some will hate it” script. I can see people reding this and going, “What the faaaahhhh??” And others going, “Holy shit. Genius!” But whether you like Galyntine or not, you walk away knowing Jason Cahill knows what he’s doing. I didn’t know anything about who wrote this beforehand. I didn’t know if he was a 30 year veteran or a first-time writer. But after a few pages, I knew this guy could write.

This is the next level of “taking a chance” TV. They said a zombie show was risky for a TV show. But people knew what zombies were. They said a big fantasy epic was risky for a TV show. But we’ve seen versions of Game of Thrones before (Lord of the Rings). In all these other “risky” shows, there were at least reference points. There’s no reference point for Galyntine.

This world is part futuristic, part ancient, part magic, part fantasy, part apocalyptic. Weird creatures. Futuristic nano-machines. It’s weird stuff.

In one of the early scenes, there’s an elaborate hunting sequence where our mountain hunters have set up pre-established trampoline-devices so they can catch the high leaping mountain elks. It’s like an operatic ballet, the way it’s described. And I know, just off that sentence, how goofy it sounds (Miss Scriptshadow: “That sounds stupid”), but Cahill makes you believe it.

Once we get to this “town,” the specificity in how this world is described – the rules behind hunting and foraging and weaponry construction and how to live off the land without destroying it – you can feel the depth here. You can tell Cahill has thought endlessly about this world.

In fact, the mythology was so specific and so extensive, I had to look up what material the script was based on. I was shocked when I googled it and NOTHING CAME UP. Galyntine is completely original. This has to be the most extensive mythology I’ve ever seen in script form that hasn’t been based on a book. I’m betting that Cahill’s been working on it for years. I bet you this was turned down everywhere until the TV boom arrived.

But Galyntine isn’t a slam dunk. Whenever you’re talking extensive mythologies, you’re talking about a burden of investment. You’re talking about setting up shit and describing shit. When you write a sci-fi, fantasy, or period pieces, you’re allowed to be extensive when describing this stuff.

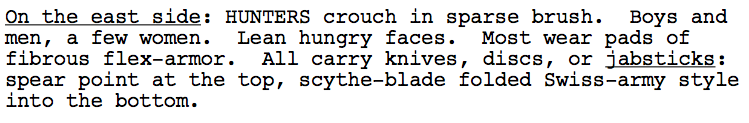

In fact, it’s encouraged. Galyntine doesn’t work if every action paragraph is one line (i.e. “Hunters prepare for their prey in the forest.”) It’s the specificity of the writing that brings the world to life, that gives it depth. Here’s the paragraph that Cahill chooses instead…

You can see how much more you gather from this description.

With that said, you can’t overdo it. Writing in fantasy is not a license to go description-crazy. You must find balance. Personally, I find that the more words a writer uses, the more insecure they are about what they’re saying. They’re using their paragraphs to figure their thoughts out, and therefore the paragraphs come off long and unfocused. Screenwriting is about finding those perfect “power” words that say what twenty words couldn’t.

“The top of his leg pale and sickly, the open wound discards his fluids haphazardly,” isn’t as good as a simple “His severed leg GUSHES blood.” We get “gushes.” I could have some friends over and engage in a 3 hour discussion about what “discards his fluids haphazardly” means and not come to a conclusion (note: I’m actually read that phrase before).

But getting back to the story, the idea with sci-fi or fantasy is you have to get to something identifiable sooner or later. We’ll give you some time to set your world up. But if you don’t give us something relatable at some point, we’re checking out.

At its core, the Galyntine pilot was a simple story about a boy who wanted a girl. His best friend then betrayed him and took her (something else we identify with) and he became frustrated with his lot in life (something else we identify with) and wanted to see what the world was like outside of this bubble (something else we identify with).

The reason to create identifiable and relatable situations in a fantasy story is because everything else is so foreign. I’ve never lived on a mountain. I don’t hunt elks with trampolines. I don’t understand weird “land” politics about where I can or can’t walk because the ground is sacred. But I know what it feels like to be rejected. I know what it feels like to want something more. That’s why that character stuff is so important to get to in your pilot.

Galyntine is a hell of a unique property. It’s so different that we’ll have no idea if it works until we see it. If it’s shot like Revolution, cheesy and cheap, it’s doomed. But if the production is approached with the same level of love and passion the script is written with, it could be incredible.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I see this a lot and it always irks me. While almost all the writing here was strong, this one line stood out to me as a no-no: “A NOISE punches the air.” A noise punches the air? What noise? What does a “noise” sound like? A noise can be 15 million different sounds! Instead of saying a “noise” is heard, tell us what the noise is! A “deep throbbing bass” shakes the ground. A “LOUD SCREECH” shoots through the hallway. A “PIERCING HIGH-PITCHED ALARM” assaults the cockpit crew. Noises need to be described.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: When a woman’s autistic son uncovers a half-century old UFO conspiracy, her life spirals out of control.

About: Writer-director David Mamet’s latest will star Cate Blanchett in the lead role. Mamet has been a writing powerhouse for 30 years. He started in plays, then came to Hollywood as a screenwriter, and eventually moved into writing-directing. He has two screenwriting Oscar nominations, with 1982’s The Verdict and 1997’s Wag The Dog. He also has two Tony nominations with 1984’s Glengarry Glen Ross and 1988’s Speed-the-Plow. At one time, he was the highest paid script doctor in town. In other words, this man is a writing badass. Mamet flaunts the fact that he was self-taught. “My alma mater is the Chicago Public Library. I got what little educational foundation I got in the third-floor reading room.” Mamet even has a type of dialogue named after him (“Mamet-speak”) where characters viciously and cynically talk over each other.

Writer: David Mamet

Details: 124 pages (October 2013 draft)

The Mamster. Mammogram. Manjambo.

I don’t know if I’d call myself a Mamet fan. But I love reading scripts from anyone who’s been a powerhouse in the industry. In the 90s, if you needed a script polish before production, this was the guy at the top of your list. You threw 2 million at him without blinking. And that wasn’t by accident. He brought the goods.

That doesn’t mean he’s infallible. The 90s were all about dialogue. Tarantino, Rodriquez, and Shane Black made sure of that. And Mamet’s dialogue could hang with any of those guys. So it made sense that they’d bring in a writer who specialized in that world.

These days, movies are more about story and character. Drama and action take precedence over a snappy comeback. Which is possibly why we haven’t seen much of Mamet lately. But this is the snazziest and most mainstream concept he’s come up with in awhile, so if there’s going to be something that puts him back on the map, this would be it. Let’s check it out.

40 year-old Janet Mitchell has just lost her grandfather, photographer Edward Mitchell. Edward was a big deal. His most famous contribution to history was manipulating a World War 2 newsreel film to make it look to the Nazis like thousands of Allied ships were heading to Boulogne instead of Normandy. Many people think that fake-out won the Allies the war.

Janet’s flown to California with her young autistic son, John, to clear out her grandfather’s home, but gets more than she bargained for when her checks stop clearing. You see, Edward’s been sending her money for the past 20 years, and under the Trust agreement, she’s supposed to keep receiving those checks. But now that he’s dead, the checks have stopped.

As she tries to figure that out, John digs around Edward’s house where he finds that his great-grandfather had an unhealthy obsession with UFOs. At first it seems like Edward helped manipulate photos to create the illusion of UFOs, but the deeper John looks, the more evidence he finds that UFOs are real, and that Edward has proof. Somewhere.

John isn’t the only one interested in Edward’s records. The army is as well. And when they get the sense that Janet and John might know something, Janet’s life starts getting weird. First, she’s framed for arson. Then that’s used against her to take away her son.

She realizes that the only way to get her son back is to locate the UFO proof that John found. But where could it be?

Soon Janet is running around like a chicken with its head cut off, going to UFO conventions and trade shows. She eventually learns of a top-secret project called “Blackbird” that her grandfather was involved in. But the project is not what we think. It deals with, of all things, the JFK assassination. Or does it? Janet’s become so entrenched in this world of conspiracies and lies that she’s not even sure if she’s sane anymore.

Blackbird was a unique reading experience, I’ll say that. It’s hard to summarize my feelings about it because it’s so unlike any other script in the genre. Which is a good thing. The last thing I wanted was a remake of that awful Mel Gibson mess, Conspiracy Theory.

But Blackbird plays its cards so close to the vest that we’re never exactly sure what’s going on, and that can get tiring in a 124 page screenplay.

What Blackbird does have going for it is the Mystery Box. You get the feeling JJ Abrams would be going nuts at this premiere, the box is so prominent. We have the mystery of why the checks stopped coming, the mystery of Edward’s obsession with UFOs, the mystery of the Blackbird Project, the mystery of the JFK assassination. And all this is tied up in the mystery of, is Janet going crazy??

At the very least, that compelled me to keep reading. I wanted to know the answers.

The problem is, there weren’t any answers for too long a period of time. This script is what I call “backloaded,” as pretty much all the good stuff doesn’t show up until the last 30 pages. That still leaves 105 pages. If 90% of the good stuff is in the last 25% of the script, you can do the math about how entertaining the rest is.

For example, we don’t get to the reading of Edward’s will until page 45. PAGE 45! The script starts with Janet already in California for Edward’s funeral. Why, then, are 45 pages needed to get us to that plot point?

Part of the problem is repetition. We’re given the same information over and over again. I think I counted six times where we’re told John thinks UFOs are real. He keeps finding new stuff inside Edward’s house to bolster this theory. But we got it already. I don’t know why Mamet felt the need to keep telling us.

Another problem is that the majority of those first 45 pages take place inside Edward’s house. I’m all for single locations in movies WHEN THEY’RE WARRANTED. Like if our characters are stuck inside a nuclear fallout shelter because their city just got nuked, being in that shelter for a long time makes sense.

But when our characters can willingly go wherever they want yet stay in a house for 30-40 pages, something starts feeling off. Especially these days, when impatient audiences need their visuals constantly changing.

But even if you took that argument out of the equation, by keeping your characters in one location for a long time, you’re creating a static storyline. The location is still so the story stops moving.

That’s not to say you can’t keep a single location interesting. There are lots of tools you can play with like conflict and mystery. And Mamet does use these. But this leads to my one big critique of Mamet’s work, which is that his roots as a playwright hamper his efforts as a cinematic storyteller.

Being in one house for so long in a play makes sense. In a movie, it doesn’t. I remember with The King’s Speech, which was originally written as a play, Tom Hooper’s number one goal was to have David Seidler rewrite it until it felt like a movie. In a now famous exchange, Hooper first came to Seidler and said, “I love this script. It’s perfect. I want to do it.” They then proceeded to do another thirty drafts. But it was warranted. It takes time to expand three locations into thirty.

Plus, thrillers are supposed to MOVE FAST. I would never write a thriller over 100 pages, especially one with so few characters. This doesn’t hamper you as a storyteller. It helps you. Knowing you have so little space to tell your story in, you’re forced to constantly get to the point. That would’ve helped a lot here, especially in that 40 page first act. Mamet would’ve been forced to ask, “Do I really need another scene where John says he thinks UFOs are real?” And all of a sudden the script is cooking along.

Then again, it should be noted that Mamet is also directing this. Since he’s essentially writing for himself (and not the reader), he’s likely taking some liberties and overwriting stuff he knows he’s going to cut later. At least I hope that’s the case. Cause this script needs to go through the chop shop. But hey, I hope he pulls it off. I’d love to see a great Mamet movie.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware backloading your script. Readers are not going to wait around for 100 pages for the good stuff to start. Mystery boxes are great, but you need to give us at least some big answers before the final act or we’ll get impatient and give up.

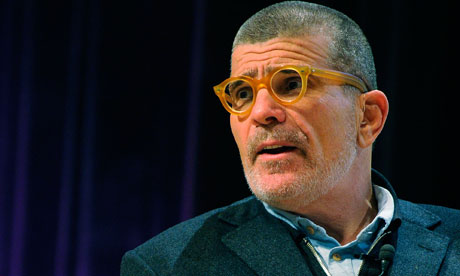

(Anyone got a caption for this photo?)

(Anyone got a caption for this photo?)

Hot dogs on the grill. Fireworks. Michael Bay. Scriptshadow Newsletter (it’s in your mailbox. Did you check your spam?). It’s the Fourth of July. Which means there’s no Scriptshadow post. But in true Scriptshadow fashion, I’m still leaving you a screenwriting tip. Try to write “crossover characters.” These are secondary characters who are part of more than one storyline. So instead of giving your hero a friend he pals around with at the bar and another friend he jokes around with at work, make the friend at the bar ALSO the friend at work. Make him cross over. I can’t begin to emphasize how much cleaner your scripts will be once you master this practice. Want 500 more screenwriting tips? Grab the Scriptshadow Screenwriting Book, which is only $4.99 at Amazon. That’s less than the cost of a pack of cherry bombs. Plus 3% of each sale goes towards defending America. That’s not true, actually. But I want it to be.

Genre: TV Pilot – Horror

Premise: A vampire strain makes its way onto a flight from Germany to the United States, threatening to unleash a plague that could wipe out humanity.

About: FX series “The Strain” is aiming to be the next big thing, FX’s answer to The Walking Dead. It’s got the pedigree to pull it off. With former Lost Exec Producer Carlton Cuse and Guillermo del Toro shepherding the show, geek blood is dripping off this thing by the bucket load. The Strain’s source material is a three-book trilogy co-authored by Del Toro and Chuck Hogan, whose 2004 book, Prince of Thieves, was turned into Ben Affleck’s, The Town. Man, self-publishing must be the way to go if even Del Toro has to do it to get something made!

Writers: Guillermo del Toro & Chuck Hogan

Details: 91 pages (June 26, 2013 draft – Production Draft).

I’ve been hearing some not-so-good things about The Strain. I’ve heard the source material isn’t so good. I’ve heard the script isn’t so good. But the talent involved gives one confidence. Del Toro’s working within the genre he’s most comfortable with (he felt a little out of sorts with Pacific Rim) and I’m a fan of novelist Chuck Hogan, who’s moving into screenwriting for the first time here. Plus, when you have low expectations, the only way to go is up.

40 year-old epidemiologist Ephraim Goodweather just got the call of his life. A plane just landed at JFK that’s “gone dark.” It’s sitting at the end of the runway without any signs of life. They need Ephraim to come in immediately and tell them what’s going on.

Problem is, Eph is in the middle of a court-appointed therapy session with his wife, who’s looking for any excuse to end their marriage. Eph having to leave in the middle of their appointment will likely be the last straw. But Eph can’t help it. In this case, he has to break the camel’s back.

But hey, it’s not like Eph’s running off to buy the latest Playstation. Lives are at risk here. Heck, this is a man who, if he screws up, an entire planet could die! So off to JFK he goes where he meets up with his sexy partner, Nora Martinez. The two board the plane to find that everyone’s dead. No signs of struggle. They’re all just sitting in their seats.

Then someone moves. Across the cabin, another body moves. 4 people have survived this mysterious phenomenon, and now Eph is hurrying to get them into quarantine. In the meantime, they trace some black light goo to the cargo bay, where there’s an old empty “cabinet” (aka, coffin) that has a lock ON THE INSIDE! Uh-oh.

Meanwhile, a crazy old man shows up begging Eph to burn the plane, the dead bodies, AND the living bodies, before “it” spreads. If doctors and scientists made decisions off the insane rantings of crazy old men, we probably wouldn’t have a planet to live on anymore. So they ignore him. Which is going to turn out to be a big mistake, methinks.

We hop back into New York where we meet Eldritch Palmer, the 3rd richest man in the world. Palmer is cavorting with pale people who don’t breathe, an indication that he’s up to something nasty. Indeed, he’s practically giddy with excitement about the news of the plane’s landing. Apparently, a long overdue event is about to occur. An event that will change the world forever.

The Strain is a competent pilot. That’s my problem with it. I want more than “competent.”

I mean we have all the ingredients for something cool, no doubt. We’ve got a mysterious plane landing where everyone is dead. We have implications of a demon/vampire unlike other iterations of vampires we’ve seen. We’ve got a conspiracy that starts with some of the richest men in the world.

While I was reading all this, I was thinking to myself, “I SHOULD be into this. So why aren’t I?”

Well, let’s start with the opening. A miscalculated opening is hard for a script to recover from. If readers are turned off immediately, they tend to keep that position throughout. Think about the last time you read a bad opening but ended up loving the script. It doesn’t happen often, does it?

The Strain’s opening wasn’t bad. But I’d seen it before. The pilot episode for Fringe was almost exactly the same, so right from the start, the story felt lazy.

From there, there were so many characters that there was no time to meet or get to know anybody. And the pilot was 30 pages longer than your average TV script. So it should’ve had plenty of time to set people up. The only person I got to know on any level was Dr. Ephraim. He was the only character who engaged in anything human, anything identifiable, via the therapy session he had with his wife.

One thing to remember is that TV is about characters. I get that the pilot has to set up the plot, but first and foremost, you have to hook us onto the people taking us through the story. Of the 20 characters introduced here, Ephraim is the only one I can visualize in my head. Everyone else was limited to a few lines of dialogue or a few adjectives of description.

One reason this may be the case? Ephraim was the only character who had to make a tough choice in the script. He’s in the middle of a marriage therapy session and he gets a call about the plane. There’s a potential disease outbreak on one side, and his marriage on the other. He’s gotta decide what’s more important. He picks the disease.

This isn’t just an example of a great way to introduce a character, but a reminder of how much more memorable someone is when they have to make a choice in a scene.

Outside of Ephraim, I’m not sure anyone here ever has a difficult choice to make. People tell other people what to do and they follow orders. No one finds themselves in a dilemma or a tough situation. It’s as if the plot is unfolding in raw form, before the writers came along and added drama to it.

Here’s what I mean. Take the scene where Eph and Nora have to check out the plane. As it’s written, they simply walk onto the plane, no problem. There’s no choice involved.

What if, instead, the airport Hazmat suits were damaged, left in a bad storage container. So Eph and Nora don’t have the proper protection to go inside. However, there are signs of life in the plane. If they don’t move fast, those people could die. Thus, a choice is presented. Go in with only threadbare protection, even though they’ll be at risk for exposure, or remain safe until better equipment comes, even though it probably means the remaining passengers will die.

And I’m not saying you have to write that scene. But you have to write “choice scenes” somewhere. You need choices. Or else there’s no drama.

In the Strain, everything’s laid out too perfectly. There aren’t enough obstacles making our characters’ lives difficult. Little troubles happen here and there (the coffin creature escapes) but it’s hard to tell how that affects things since we don’t understand what’s happening yet. In the end, I never felt that afraid or worried for anyone, which is strange when you consider that the fate of the world is at stake.

So, sadly, The Strain didn’t work for me. It’s not bad. But it left me wanting more. It needed more originality, better character setup, and more going wrong for the characters. Adding 5-6 more tough choices for people would’ve helped a lot.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Repeat offender. Don’t use an adjective in your description, then quickly follow that with the same adjective in the dialogue. It reads lazy. So in The Strain, one of the characters is described as having “waxy” hands. Then, half a page later, one of the characters says, “Anything happens to her, I’ll find your waxy ass.” The repeat use of the word gives the text a lazy and uninspired feel.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre (from writers) Historical Action

Premise (from writers): In 30 A.D., a charismatic stonemason bent on revenge leads a band of guerrilla rebels against the Roman occupation of his homeland.

Why You Should Read (from writers): This is the story that led up to the biggest trade in human record. It is Braveheart meets Gladiator, with characters on a collision course that splits history in two. Come for the battle, the intrigue, and the epic. Stay for the sacrifice, the betrayals, and the passion that drives a man to darkness. — As co-writers, we work from 3,000 miles apart. Yes, we have two of the WASPiest names imaginable. No, they’re not pen names. We’ve been polishing this script to a trim, accelerative tale that strengthens, weaves, and deepens with each choice our characters make. The ending is the most difficult we’ve ever worked on, but the feedback on the resolution has been powerful. We have to earn the effect we want a story to have, and with this script we aim to challenge, to provoke, but most of all…to entertain.

Writers: Parker Jamison & Paul Kimball

Details: 112 pages

Man, the last couple of days have been carraaaa-zy in the comments section. The Comments Post did not go over well with a lot of you. Miss Scriptshadow’s review caused a nuclear-sized meltdown in the Grendl-verse, and some manic derilect from 2011 topped it all off with a bunch of “Carson is evil” comments.

Today, however, it’s going to be all about the script. If you want to talk about other things, feel free to go back to those earlier posts. But I want today to be about the writing, specifically Barabbas. I’ve already read Barabbas once for a consult and I liked it with reservations. So I’m really glad you guys picked it as a healthy discussion should continue to strengthen the script even more.

The story is not without its challenges. It puts itself in some unenviable writing situations, which I’ll get to after the summary. I’m also interested to see what these guys have done with the latest draft and how much the script has improved. Let’s take a look.

“Barabbas” offers something whether you’re familiar with the story of the man or not. If you’re like me and had never heard of him, Barabbas plays out like a slow-burning quasi-mystery, pulling in familiar elements from religious history that eventually lead to a shocking finale.

If you do know Barabbas’s name, the script plays out like “Titanic.” You know where this will eventually end up, so you’re curious what’s going to happen to get us there.

Joshua Barabbas, 30, is a stone mason. Along with his younger brother David, the two build bridges and aqueducts for the Romans who, at the time, were occupying Jerusalem. When the Romans raid the Jews’ own temple to pay them their wages, David and Joshua have had enough, and rebel.

When their friend is erroneously chosen as the instigator of this rebellion and crucified, an angry Barabbas is persuaded by a local politician, the sinister Melech, to start a war. Using rage to guide his leadership, Barabbas and his fellow workers attack the Romans, but eventually flee to the mountains once outnumbered.

Realizing that there’s no turning back, Barabbas starts to grow a small army with the hopes of driving the Romans out of Jerusalem. But when Barabbas falls for the wife of a key ally in the city, he loses focus, and the rebellion begins to fall apart.

In a last ditch effort to recruit a huge army from the surrounding regions, Barabbas designs a plan to take down the Roman Regional Governor Pontius Pilate. (major spoilers) He ultimately fails, and his life hangs in the balance of the people themselves, when they must choose which of two men shall be set free, Barabbas or Jesus Christ.

I knew this weekend’s Amateur Offerings was going to be good because I’d read two of the scripts and knew both were solid (the other being “Reeds in Winter” about the infamous Donner Party, which ended up in some gnarly cannibalism). The rub? They were both period pieces, which are the hardest to get readers on board with. Therefore it was satisfying to see them both end up with the most votes, as it shows that readers still respect challenging material.

With that said, each script has its trouble spots. Assuming the reader sticks around long enough to get into the story, which is never a guarantee with period pieces, I was always worried about that darned Barabbas second act.

The problem is this – the second act is where countless scripts go to die. It’s hard as hell to keep it interesting even under the best of circumstances. In Barabbas’s second act, our army is relegated to a single location up in the mountains. Keeping a “swords and sandals” period piece lively when the main character and his army are relegated to one spot for 60 pages is as challenging a proposition as you’re going to find in screenwriting.

Compare that to Braveheart. The great thing about that film was that William Wallace kept moving across the country to bigger and bigger cities, so we got this sense of BUILDING as the story went on. That’s harder to do when characters are hiding in caves in the mountains, especially when you’re limited by history. Barabbas’s army couldn’t have gotten TOO big or else he would’ve been more well known in the history books. Barabbas’s one defining characteristic in the bible is that so little is known about him.

But my gut’s telling me we need to either get Barabbas off that mountain space at some point, grow his army bigger in some way, or find some other means to spice up the second act.

What if, for example, Barabbas had to go out on some recruiting trips into the surrounding cities? If we built up certain meetings with city leaders he would have to win over in order to receive their soldiers, that’d be one way to keep the story dynamic.

Getting him off the mountain to meet Jesus at some point would be interesting as well, but Parker told me he doesn’t want to physically see Jesus until that final scene, which I understand.

Another thing that bothered me during the initial read, and something I don’t think Parker and Paul have addressed yet, is the character of David, Joshua’s brother. Over the course of the script, David sees Jesus speak (we don’t see this) and starts to respond to his teachings. Whereas Barabbas wants war, David preaches forgiveness and peace.

The problem is that all of this happens too late and doesn’t have enough conviction. I was bothered, for instance, by a character named Thaddeus, who comes into the story late to aggressively preach Jesus’s philosophy. I couldn’t understand why this character wasn’t David. In order to get the maximum amount of conflict from a relationship, you need the two characters to be on opposite sides of the philosophical spectrum. David was tepid in his support of Jesus’s teachings until the very end. Let’s have this guy go out there, see Jesus speak, and let him be the one who comes back and starts aggressively converting the other soldiers. Now you have a direct conflict. Barabbas needs soldiers to take down Pontius and his own brother is turning those soldiers into pacifists. Isn’t that better than Random Thaddeus, who I met five minutes ago, who has no allegiance to anyone, converting these people?

One of the complaints about Barabbas during AOW week was dialogue. Most people said it was serviceable, but that serviceable isn’t good enough in a spec trying to stand out. And I’d agree with that. But fixing this is a lot easier said than done.

What I believe people are responding to here is the lack of “fun” in the dialogue. People always seemed to speak in a proper and serious way. “You still labor at the aqueduct?” “Every day. Why?” “I’ve heard that funds are running short. That Pontius Pilate needs extra coin to finish it.” “As long as the Romans pay, we work.” This is a conversation between two people who have secretly loved each other since childhood. You’d think they’d have a more relaxed and easy rapport, right?

But the biggest issue here is that almost EVERYBODY spoke like this or very similar to this. So the problem might not be “dialogue” so much as “variety in dialogue.” I always talk about creating “dialogue-friendly” characters. People who have fun with the language and say things others wouldn’t. It would be nice if a featured character here were dialogue-friendly. From there, look at every character and figure out ways to make them speak differently from everyone else.

Finally, I wanted more out of the ending. I think the problem here is that Parker and Paul see the sacrifice at the end as the climax. Which it is. But before we get there, we need to give the audience the climax they’ve been waiting for, the one we’ve been building up for 80 pages, which is an attack on Pontius Pilate.

Let’s see him and his army try to head Pontius off at the pass on his way to Jerusalem. Let’s see him almost kill Pontius. He ALMOST does it! But something at the last seconds prevents him from succeeding and he’s captured.

Then, since it’s now personal between him and Pontius, we can see Pontius, behind-the-scenes, preparing Barabbas so that he’ll be the one picked for crucifixion by the people. Pontius makes him extra dirty and nasty looking, in the hopes that he’ll be the one killed.

I know we’re playing with fire here, but it could be an ironically delightful ending to see that Pontius had a horse in the race and was hoping to snuff out Barabbas, which, of course, would’ve changed history. He’s visibly disappointed, then, when Jesus is chosen instead.

Whatever these guys choose to do, though, I trust them. Barabbas is not perfect, but it shows a lot of skill, and it shows two writers who are going to make a splash at some point if they stick with it. I don’t know if it’s going to be with this script because, again, the subject matter is challenging, it’s a unique sell, and there’s that whole second act issue that I’m not convinced is solvable. But I just like these guys as writers and hope to see more work from them in the future.

Script link: Barabbas

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Use specificity instead of generalizations when writing description. Today’s “What I learned” actually comes from Casper Chris, who I thought made a GREAT observation when he compared two action paragraphs from Barabbas and Braveheart during AOW. Here were the two he compared…

Barabbas:

Barabbas leads the charge. The rest of the stonemasons pour down on the patrol. Slashing, spearing, hacking. Barabbas fights like a barbarian, fearsome and brutal. Ammon slices through soldiers with precision. David is quick and athletic.

Braveheart:

He dodges obstacles in the narrow streets — chickens, carts, barrels. Soldiers pop up; the first he gallops straight over; the next he whacks forehand, like a polo player; the next chops down on his left side; every time he swings the broadsword, a man dies.

Notice the difference. Whereas the Barabbas text uses mostly general words to describe the action (“slashing, spearing, hacking” “fights like a barbarian” “quick and athletic”), Braveheart uses specific imagery. There are more nouns here and the verbs are used to highlight powerful actions (“chickens, carts, barrels” “soldiers pop up” “he gallops straight over”). It was a great reminder that we need to put specific imagery into the reader’s head so he can properly imagine what’s happening up on the screen.