Search Results for: F word

Tarantino’s writing probably contains more exceptional elements than any other writer in the business.

Tarantino’s writing probably contains more exceptional elements than any other writer in the business.

The worst scripts in the world? They aren’t the worst scripts in the world. There are scripts even worse.

Make sense? Probably not. But it will be by the end of this article.

Consider yourselves lucky. Here at Scriptshadow, we don’t let you see the bad stuff. The scripts you see on Amateur Offerings every week? Those writers have at least demonstrated an understanding of the craft. But the truly bad ones? Those don’t make it in front of your eyes. For that reason, you don’t know what it’s like to read something truly bad.

I remember a couple of years ago, I read this script where I had ZERO understanding of what was going on. This writer had the ability to write pages and pages of story where nothing actually happened, so I’d find myself having read 10 pages, but not being able to remember anything that transpired. If you put a gun to my head, I’d probably tell you it was about a goddess trying to blow up a volcano. But if the writer had told me it was about a Christmas tree who fell in love with a menorah, I wouldn’t have argued. It was that vague.

But look, the truth is, these “really bad” scripts are often the result of new writers who haven’t studied the craft and who have never gotten feedback. They write down exactly what’s in their head as they’re thinking it, believing it will make sense to us because it makes sense to them, not realizing that writing a screenplay requires a stricter kind of logic that takes some trial and error getting used to.

So to me, those aren’t the worst screenplays. The worst screenplays are the AVERAGE SCREENPLAYS.

There’s no emptier feeling I get than when I read an average screenplay. I mean, at least with a really bad script, you remember it. With an average script, it’s forgotten as soon as you put it down. It goes through you like fast food. And the sad thing is, I’ve been reading 15 of these scripts a month. It feels like this huge collective of screenwriters has accepted mediocrity. So when I see the spec market starving, it doesn’t surprise me. Who’s opening up their checkbook for another average script?

Let me give you an example. I once read a buddy-cop script (I had to go back to it to re-familiarize myself) that had the two cops who hated each other, it had the standard “witty” back-and-forth banter, it had the familiar drug plot, it had the cop who was secretly one of the bad guys. This is the exact dialogue going on in my head as I read it (“Seen that before. Seen that before. Seen that before. Seen that before.”). I must’ve said that to myself 80 times. There wasn’t a single elevated element in the story.

I don’t know what writers expect after writing these scripts. Do they think they should be praised because they successfully gave us an average version of something we’ve already seen before?

With a script, you have to stand out somehow. A series of average elements isn’t going to cut it. Readers want to see original takes on elevated material. Which brings us to the term of the day: Exceptional Elements.

An exceptional element is any element in your script that’s better than average. You’d like to have as many of these in your screenplay as possible. But realistically, you probably won’t get past 3. Which is fine, because that’s all you need to write something noticeable, and definitely all you need to write something better-than-average.

To add some context, there are three scripts I really liked over the last few weeks: Hot Air, Cake, and Tyrant. Let’s see what the exceptional elements were in each. With Hot Air, the dialogue (especially Lionel’s) was an exceptional element, the characters were an exceptional element, and the plotting was an exceptional element (I never quite knew where things were going next).

In Cake, the creation of a severely unlikable protagonist who we still ended up caring about was an exceptional element, the unusual premise was an exceptional element (haven’t seen that before) and the unique voice (the offbeat weird way the writer saw this world) was an exceptional element.

In Tyrant, the intricate nature of the relationships were an exceptional element, the lack of fear in pushing the boundaries was an exceptional moment (a few uncomfortable rape scenes, etc.) and the ending was an exceptional element (in that it revealed something shocking about our main character that we never would’ve guessed).

Before we get into specifics here, I want you to think about the screenplay you’re working on now. And I want you to take off your bullshit hat. Put your critics hat on, the guy who can tear down the latest blockbuster in a 300 word paragraph. That’s the guy we need judging your script. Now ask yourself, what are the exceptional elements in your script? What can you honestly say stands out from anything out there? Need some reference? Here are a dozen of the more popular screenplay elements to choose from. If you’re exceptional with just three of them, tell us in the comments section, cause we’re going to want to read your script.

Clever or unique Concept – One of the easiest ways to elevate your script is a great or unique concept. Dinosaurs being cloned to make a Dinosaur Theme Park (Jurassic Park). People who go inside other people’s heads (Being John Malkovich).

Unique or complicated characters – This is a biggie. If you’re going to have only one exceptional element, it should be this, because a script is often defined by its characters. Give us Jack Sparrow over Rick O’Connell (Brendan Frasier in The Mummy). Give us Jordan Belfort (The Wolf of Wall Street) over Sam Witwicky (Transformers).

Spinning a well-known idea – Taking ideas and spinning them is one of the easiest ways to stand out. Instead of that same-old same-old buddy cop script I talked about earlier? Make it two female cops instead (The Heat). Or set some ancient story in a different time (Count of Monte Cristo in the future – a script that sold last year). This is what’s known as a “fresh take,” and Hollywood loves fresh takes.

Take chances – How can you expect to be anything other than average if you don’t take chances? Playing it safe is the very definition of average. So you’ll have to roll the dice a few times and get out of your comfort zone. Seth McFarlane made a comedy about a grown man who was best friends with his childhood teddy bear. Nobody had ever written anything like that before. That’s rolling the dice.

Push boundaries – This will depend on the script. But if you’re writing in a genre that merits it, don’t play it safe. Push the boundaries. That’s what Seven did when it came out. We’d seen serial killer movies before. We’d never seen them with kills that were THAT sick, that intense.

Plotting – A deft plot that keeps its audience off balance (with mystery, surprises, dramatic irony, suspense, setups, payoffs, twists, reversals, drama, deft interweaving of subplots, etc.) can put you on Hollywood’s map. Hitchcock’s big exceptional element was his plotting.

A great ending – A masterful ending is a huge exceptional element because it’s the last thing the reader leaves with. If you can give them something immensely satisfying (The Shawshank Redemption) or shocking (The Sixth Sense) and it works? You’re golden.

Dialogue – One of the hardest elements to teach and the most dependent on talent. There are definitely ways to improve your dialogue, but usually people are either born with this element or they aren’t. Don’t fret if you aren’t though, because you still have all these other elements to choose from.

Imagination – If you’re writing fantasy or sci-fi, you better show us something we haven’t seen before. For example, if you’re going to put your characters in yet another mech suit (Matrix sequels, Avatar, Edge of Tomorrow), why should we trust you to give us an imaginative story? These are the genres that demand originality. So if you don’t have anything besides what you’ve seen in previous sci-fi movies, don’t play in this sandbox.

Voice – If you see the world in a different way from everyone else, it’s one of the easiest ways to stand out. This is all about the unique way you write and the unique way in which you observe the world. Having a truly original voice is almost the anti-average, because if someone can identify who you are by your script alone, it means you have a unique take on the world.

Scene writing – Are you an exceptional scene writer? Are you able to pull readers into every scene? Read Tarantino’s scenes like Jack Rabbit Slims or the Milk scene at the opening of Inglorious Basterds. Or watch the scene where the detective questions Norman Bates in Psycho. The level of suspense in these scenes is off the charts.

A great villain – Typically someone who’s complicated and not just evil for evil’s sake (which is the case in almost every average script I read). I still can’t get over The Governor in The Walking Dead. The way he fell in love with a woman and cared so deeply for her daughter, only to set up a plan to kill women and children a few scenes later.

In general, to avoid writing something average, you have to be your harshest critic. You have to be self-aware enough to call yourself on your bullshit. Look at every individual element in your screenplay and ask yourself, “Is this unique?” In some cases, it won’t be. That’s fine. As long as you have exceptional elements to offset the average ones. The Heat had an average plot. But by putting two women in the cop rolls instead of men, it gave the genre a fresh take. Exceptional element success.

The truth is, readers really want to love your script. But you’re preventing them from doing so when every element in your screenplay is something flat, derivative, uninspired, or rushed. Writing a great screenplay means doing the hard work, and that means not being satisfied with a bundle of average components. Average dialogue, average scene-construction, average concept, average imagination, average characters. We’ve already seen all these things so what do you gain by showing them to us again? Get in there and raise the quality of your script by infusing it with as many exceptional elements as you can. I’m rooting for you because the better you get at this, the more good scripts I get to read. Good luck!

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: BROKEN

GENRE: Sci-fi/Disaster

LOGLINE: When the human race is forced to evacuate earth for the moon, it leaves behind a crusty old engineer who finds new purpose in the company of a mute nine-year-old girl.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’ve had a dozen different writers read this script and give excellent, detailed notes on it–which of course called for a complete rewrite. A month later, this beauty’s been retooled, buffed and polished; she purrs like a tigress, 95 pages of lean muscle, just itching for baptism in the fiery crucible of the AOW. Hm, was that a mixed metaphor? …Nah.

Other interesting facts? At one point the protagonist is trapped in a bunker while an earthquake rips it apart, while performing invasive surgery on himself, WHILE conversing with a hallucinatory version of his former girlfriend.

And by the end of this script, I hope you’ll have fallen in love with a bitter, grouchy, hateful, suicidal old man. Who doesn’t save any cats. Thanks for reading, and enjoy!

TITLE: Barabbas

GENRE: Historical Action

LOGLINE: In 30 A.D., a charismatic stonemason bent on revenge leads a band of guerrilla rebels against the Roman occupation of his homeland.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This is the story that led up to the biggest trade in human record. It is Braveheart meets Gladiator, with characters on a collision course that splits history in two. Come for the battle, the intrigue, and the epic. Stay for the sacrifice, the betrayals, and the passion that drives a man to darkness.

As co-writers, we work from 3,000 miles apart. Yes, we have two of the WASPiest names imaginable. No, they’re not pen names. We’ve been polishing this script to a trim, accelerative tale that strengthens, weaves, and deepens with each choice our characters make. The ending is the most difficult we’ve ever worked on, but the feedback on the resolution has been powerful. We have to earn the effect we want a story to have, and with this script we aim to challenge, to provoke, but most of all…to entertain.

TITLE: THE SORCERER

GENRE: Mystery, Bio-Pic, True Story

LOGLINE: When brilliant-but-forgotten inventor Nikola Tesla dies mysteriously at the height of World War 2, a couple of FBI Agents race to discover the whereabouts of his final creation – a devastating and world-changing death ray – before it falls into the hands of the Nazis, and along the way put together the clues that reveal the deepest mystery behind Tesla’s life: what drove him to madness.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Tesla’s life was fascinating. He came from nothing and rose to the height of his profession, battling it out with Thomas Edison and JP Morgan, becoming friends with Mark Twain and George Westinghouse, and electrifying the world…only to die penniless and alone after seeming to lose his mind. He’s also a man relatively few people know about when compared to his peers. If you like mysteries without easy answers, smart and ruthlessly powerful men pioneering the future, and/or underdogs who never stop going for their dreams, you can find something for you in this story.

TITLE: Finishing Last

GENRE: Comedy romance

LOGLINE: A third generation car salesman attempts to transform his nice guy personality to save career and in doing so finds himself attracted to a quirky woman who loathes the new him.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: It’s a feel good comedy romance, which has the following:

No sex… well maybe a small amount. In fact, I’d hardly call it sex, more like a reference to it. No gratuitous violence… I don’t think a kick in the nuts is gratuitous? Maybe mild violence at the most. No bad language… Okay a few F-words, but you’d have to be a saint to be offended by that.

I don’t think I’m selling this very well?

It’s a low budget… no, that just makes it sound cheap. It’s a story of unrequited love… that sounds better… and written for the sole purpose of having an amusing story that couples could go and see together. It does not pretend to be anything but a humorous love story with some oddball characters… I’m rambling now. I’m really not selling this. I’ve been told it has some charm… God; it just comes over as being smug.

Anyway, I think you might like it.

TITLE: Reeds in Winter

GENRE: Historical Adventure/Love Story

LOGLINE: Forced to leave the family he loves, a man who misused his wealth to move his family across the country with the infamous Donner Party must do whatever it takes to rescue them from freezing, starvation and cannibalism.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: If I were to say I wrote a script about the Donner Party, I think I could feel your eyes roll to the back of your head. While the backdrop of my story includes the Donners, they are not the main focus. There were many families who traveled on that infamous journey, and one family, the Reeds, overcame very tragic events and survived intact. I worked hard to keep the bits that I felt would make a great movie, and, if you’re interested in history, look them up because that shit really happened. The story made me think about what lengths I’d go through to ensure the safety of my family. I don’t know if I could ever do what James Reed had to do, and I hope I never find out.

Today I want to talk about opening scenes. You guys have heard over and over again how important the opening ten pages is. That’s true. But I would actually scale it back further to the very first scene. Let me tell you why. Not only does the first scene have to engage the reader, but this is when the reader’s “are you any good” antennae is at its most sensitive. They’re looking at every little word, every little comma, every little detail, to see if you know what you’re doing. The more errors they see, or the more something feels off, the less confident they get in your ability to deliver. For example, if they see this sentence…

How you doing Jake?

Instead of this one…

How you doing, Jake? (with a comma before “Jake”)

…they get worried. Or if a writer uses some weird formatting structure they’ve never seen before, they get worried. If someone doesn’t know basic punctuation or screenplay formatting, how much effort have they really put in to learning how to write? Don’t worry, today’s article isn’t a glorified quiz on Strunk and White’s “The Elements of Style.” I just want to point out that every little detail matters. What I really want to focus on is writing an opening scene that PULLS THE READER IN.

Remember, a screenplay isn’t like a novel, where the reader goes in knowing they have to put in some groundwork to get to the good stuff. A Hollywood reader expects to be entertained right out of the gate. This doesn’t mean that all scripts will be like this. But the vast majority are.

A lot of writers hear this directive and fight it. “Well what if I’m writing a slow-burn drama?” they ask. “What am I supposed to do then? Start with a car chase that makes no sense within the context of my story, just so the reader pays attention?” No, that’s not what I’m asking here. To be honest, starting with a car chase can be just as boring as starting with two people talking, if it’s not constructed properly. What I’m looking for out of an opening scene is something that’s DRAMATIZED, something that pulls you in via the design of the scene.

Regardless of how you choose to do this, you should always try and jump into your story right away. If you’re making a movie about a killer shark, start with a shark attack. If you’re making a movie about a private investigator, give him a case immediately. If your movie’s about a killer asteroid, start with a stargazer who spots the asteroid in his telescope. You won’t always be able to do this, but you’ll notice from the movie examples I use below, almost all of them fit this criteria.

OPTION 1 – CONFLICT/TENSION

Write a scene using conflict or tension. Look at the opening of Fargo. A guy walks into a seedy bar and sits down opposite a couple of criminals. They immediately start arguing about what time everyone was supposed to be here. This argument leads into a second argument about money, which one side believes was supposed to be delivered today, while the other insists isn’t due until later. It’s a tense scene. — Now personally, I find conflict to be one of the weaker ways to start a story. Conflict works best after you’ve gotten to know the characters and understand their differences and WHY they clash. So if you’re going to use it in your opening, make sure you’re setting up your story as well. That way, you’re killing two birds with one stone. With Fargo, the opening is not only characters clashing, it’s setting up the kidnapping of our main character’s wife, which is the hook of the film.

OPTION 2 – SURPRISE

Use your opening scene to surprise the main character, the reader, or both. Look no further than Source Code and Buried. Source Code starts with our main character waking up in a train with no memory of how he got there. Same with Buried (a man wakes up in a coffin). Note that surprise can lead to mystery, which helps keep the reader hooked going forward. In Source Code, our hero has to figure out what he’s doing here, which fuels the next 10 scenes or so.

OPTION 3 – SHOCK

Using shock as a way to grab a reader can be cheap, but it can also be effective, as long as you’re not just shocking the reader to shock them, but rather setting up your story. Say we’re enjoying a family Christmas with the perfect upper middle-class family. Mother, father, son and daughter are all having a wonderful time opening presents. Then finally the dad turns off camera. “Your turn, Larry. Which present do you want us to open?” Slowly pan over to see Larry, a 17 year old retarded boy naked in a cage wearing a gimp mask, grunting strangely. Cut to black. Shock is perfect for horror films, but can be used in any genre. Maybe your star CEO protagonist who’s just closed the biggest merger in his company’s history gets called into the Board of Trustees where he thinks he’s getting a bonus. Instead, the Trustees sit him down and tell him he’s fired. That’s just as shocking. Well, okay, nothing’s as shocking as Larry the Christmas Gimp Child.

OPTION 4 – MYSTERY (CARSON’S PICK!)

Probably the best way to start a script is via mystery. That mystery can be paid off right there in the scene itself or it can be paid off later. In Back To The Future, Marty walks into Doc’s house, where we see the dog food has gone uneaten for days, there’s a box of plutonium under the bed, and Doc calls to say (in a hushed tone) he needs to see Marty later about something important. Are we going to keep reading? Of course we are! We want to find out how all those things come together. Or, you can create a mystery that pays off right there in the scene. In the above mentioned Fargo scene, in addition to the conflict between the characters, there’s a mystery as to why they’re all here. The Coens wisely don’t tell us right away, which is part of what keeps us hooked. Eventually, Carl says, “You really want us to do this? You want us to kidnap your wife?” And the mystery is answered.

OPTION 5 – SUSPENSE

There’s a little bit of an overlap between mystery and suspense, but essentially, with suspense, you set up a question then draw things out before giving your reader the answer. The more high stakes the question, the more powerful the scene will play. An obvious version of this is a pregnancy test. Show a nervous 17 year old girl sitting on a toilet. Push back to see she’s holding something under it while looking at a pregnancy test box. From this point, the suspense has started. She reads, “Wait 3 minutes,” on the box, gets up, flushes, and waits. Are we going to wait around to see what happens? Of course we are! We want to see if she’s pregnant. And we know that since she’s only 17, this is a big fucking deal. But the real fun in suspense is how you play with the scene(s) in order draw the suspense out! So maybe while our teen is waiting, her annoying MOM bursts into the bathroom. The girl immediately drops the pregnancy test in the garbage before her mom can see it. “Jesus, Mom, ever hear of knocking?” “Sorry dear, just cleaning.” Oh no! The girl watches in horror as the mom picks up the bathroom trash bin and dumps it into her trash bag and leaves! Our teenager then must wait until her mom takes the garbage out. Once she does, she races out and starts digging through the trash. Finally, she spots the test and grabs it. “You one of those freegans now?” comes a voice from behind. She turns around. It’s the hot guy from next door! She hides the test behind her. (Etc., etc. You get the idea).

OPTION 6 – UNCERTAINTY

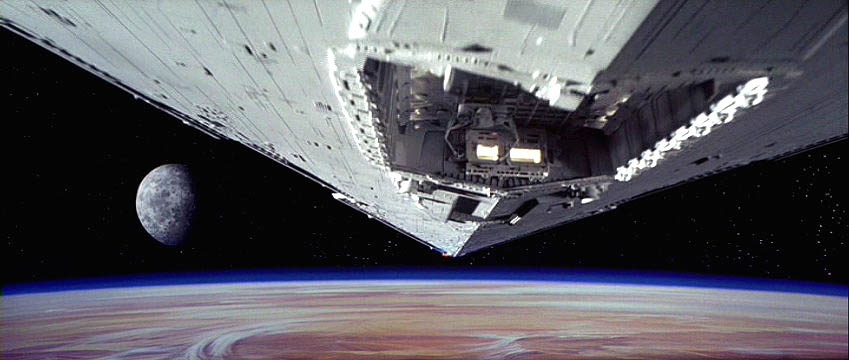

If all else fails and none of these methods works for you, just come up with a scene where something is HAPPENING (characters are acting or being forced to react), then create a sense of uncertainty about what’s going to happen next. In Star Wars, a weird black-clad character in a cape sucks a tiny ship into his super-cruiser then invades the ship looking for something. Here, we have elements of mystery, of suspense, we’re meeting characters on both sides of the fray, but most importantly, everybody is acting or reacting. You see this same thing in the opening of The Matrix.

The biggest mistake I see in opening scenes (and really, opening acts) is writers SETTING UP their story instead of DRAMATIZING IT. The first few scenes will set up the town, the main characters, the rules. A lot of time, these openings are beautifully written, but they’re boring as hell because NOTHING’S HAPPENING. And by “nothing’s happening,” I mean there’s no drama. It’s just a bunch of description (of people, their lives, their places, their things). You have to introduce your world in a dramatized way if you want the reader to keep reading. In general, be wary of opening with any scene that has characters sitting or standing around talking. Preferably, they should be acting, trying to obtain something or going somewhere to do something important. Give them a purpose so that we’re immediately engaged in their pursuit. If you do want to start with people standing or sitting around, create a big mystery or use a lot of conflict. If you don’t, you could be in trouble.

Of course, there may be some things I’ve forgotten here. Anyone else have suggestions on how to open a screenplay? I’d love to hear them in the comments.

note: Been having trouble moderating. Some comments might not appear for awhile but they WILL appear at some point, I promise.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: After nearly dying in a car accident, a mechanic is given an experimental drug while in a coma. When he awakes, his IQ begins to skyrocket.

About: This is not the first Eric Heisserer/Ted Chiang collaboration. For those of you who get the newsletter, you’ll remember when I reviewed their previous collaboration, Story of Your Life (about an alien visitation that requires a linguist to help communicate with the ETs). The project has since secured Amy Adams for the lead role (she’s perfect) and Denis Villeneuve to direct. You may know Villeneuve as the director of another big spec script, Prisoners. Heisserer previously wrote The Thing remake and Final Destination 5. He’s since moved into directing, last year helming the Hurricane Katrina thriller, Hours, which starred Paul Walker.

Writer: Eric Heisserer (based on the short story by Ted Chiang)

Details: 116 pages (undated)

One of my favorite scripts from the last couple of years is Story Of Your Life. It took a big idea and approached it from a very intimate place. Sort of like M. Night’s “Signs,” but way better (and more original). As a screenwriter, this strategy is one of the best ways to get noticed, as you’re giving producers two things they want – a big concept and a story that can be shot on a reasonable budget.

But they’re not easy to write. Because of the tiny scope, the writer often ends up running out of engaging material. Look no further than one of the WORST movies I’ve seen this year, 2008’s Pontypoole (caught it on Netflix). It’s about a zombie outbreak that takes place entirely inside a radio DJ booth. Somewhere around minute 30, they ran out of stuff to do, and the rest was just, well, awful (they eventually figure out that the zombie outbreak is spread though…VOICE! So just by talking, the DJ is spreading the zombie virus! I’m not kidding!).

If you can prove yourself in that realm (your movie actually gets made), that’s when the gatekeepers trust you with a bigger budget. Which leads us to today’s script, the oddly titled, “Understand.”

30-something David Miller is a lowly car mechanic who, you get the feeling, hasn’t ended up where he thought he would. The one thing he’s got going for him is his beautiful wife, Lauren. One day after work, he picks her up and the two drive home like they always do.

Except before they get there, they get rear-ended into an icy river, where poor David watches his wife drift away. Three months later, David wakes up in a hospital room from a coma. He’s been told by his doctor that in order to get him out of the coma, they had to use an experimental drug.

As the days pass, David starts to feel smarter and starts craving knowledge. But this newfound intelligence comes with a price. The doctors won’t let David leave. Whatever this drug they injected him with is, it’s less about helping him and more about making him their lab rat.

The great thing about being super-smart though, is that you can outsmart the dumbos. And David’s able to escape with minimal effort. Once out in the wild, his intelligence continues to grow, allowing him to do things like learn Taekwando in the time it takes to check your e-mail and fly a Cessna plane with a three-minute prep course.

David quickly realizes why the doctors wanted to watch him so closely. David isn’t just becoming smart. He’s becoming a weapon.

Soon, David learns of a previous recipient of the drug he was given, another escapee named Vincent, who is a month ahead of him in the trials. Being one month ahead means having 30 additional days of intelligence growth. David may be a genius. But Vincent is the equivalent of 20 geniuses. David’s purpose shifts from eluding his pursuers (which now include the FBI) to stopping Vincent, who appears to be prepping an attack that could be the precursor to the end of the world as we know it.

“Understand” is a unique and entertaining piece of material. It’s sort of like Limitless meets The Bourne Identity meets Transcendence meets The Matrix meets Highlander. If there’s a hiccup in the script, it’s just that – it may be trying to do too many things.

For me, the script seemed to set itself up as an intimate thriller, possibly something that took place entirely in the hospital. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, it becomes a traditional “man on the run” Liam Neeson vehicle. It was during this section that I began to lose interest, since we’ve seen a bajillion of these thrillers already. The fact that the rapid-intelligence thing had been done fairly recently in Limitless didn’t help either.

But then Chiang and Heisserer start to get trippy, with David’s intelligence becoming so advanced that he can actually calculate where bullets are going to go before they’re shot, allowing him to dodge them (or, in some instances, deflect them with a knife blade).

However, once Vincent (the other super-smart guy) becomes David’s nemesis, the script almost becomes a super-hero movie, with the two fighting on top of buildings with super-advanced sparring skills. Heck, they eventually get so smart that they can move things with their minds, throwing yet another influence, Star Wars, into the mix.

What’s happening here is not a unique problem. Sometimes, for a reader to buy into a world, it requires the writer to slowly take us through the steps. In other words, it would be stupid if David could use telekinesis right away. But after we’ve seen him “level up” several times, it makes sense.

But if you take too long before introducing the REAL story (in this case, the emergence of Vincent and his diabolical plan), the reader can become confused. Oh, they say, I thought this was about a guy running away from the government. But it’s actually about a battle between two genius super-heroes.

The thing is, I mostly run into this problem with inexperienced writers who haven’t yet learned how to keep a consistent plot thread going for an entire script. They want to throw in new bells and whistles to keep your interest, not realizing that each one takes us further away from the original story we thought we were reading.

That’s not the problem with Eric’s script. He still knows what he’s doing so he makes it work. I just thought it felt a little unbalanced, with Vincent becoming this huge story agitator too late in the game.

The only other major observation I had was David’s job. David is a mechanic, which I thought was an odd choice since it had nothing to do with the story. There was ONE major payoff of him being a mechanic (he disabled the bad guy’s car), but if David is as smart as we’re led to believe, he should’ve been able to figure this out anyway.

We writers do this a lot. We absolutely LOVE a good payoff. But sometimes we love them so much that we’ll keep the setup to that payoff even if changing it would improve everything else in the screenplay BUT that payoff.

So say I was writing a comedy about an airplane pilot who can’t tell a lie for one day. The reason I made my main character a pilot? It’s a setup to an awesome payoff late in the script where my hero escapes the bad guys by hijacking a plane! Sure, that’s a nice payoff, but if I made my character, say, a lawyer instead, the setup would be a lot more ironic and lead to ton more funny scenes (Liar Liar). So you have to ask yourself, is keeping your main character a pilot so you can have that plane hijack scene really worth it?

I don’t think David being a mechanic is milking the irony of the situation enough. Flowers for Algernon (another “turn to genius” story) made its main character mentally retarded so that the irony level was high when he became smart. I don’t think that’s right for this particular script, but maybe they could do what Good Will Hunting did and make David a low level worker at a place known for the high intelligence level of its employees, like a giant bank or a huge trading firm.

By no means is going with a mechanic a bad choice. I just think if you can milk the irony of a concept, you do it. As a screenwriter, you don’t want to leave any stone unturned when you write a script. Always try to get the best out of every single element.

Anyway, “Understand” was a little schizophrenic but extremely well-written and moved at a speed-train like pace. The weird second half turn did throw me, but it also kept me off-balance, so I didn’t know what would happen next. I’d recommend this one if you can find it!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Number of times I checked the internet during read: 7

What I learned: Ahhh, I do not like numbered montages.

1) Frank works at his desk.

2) Frank and Sara sit at home, reading.

3) Frank goes fishing with his buddies.

4) Frank back at his desk, working.

I’m a big believer in keeping the writing as invisible as possible. The idea is to make someone forget they’re reading so they’re always immersed in your story. Anything you do to disrupt that reminds them it’s just a big fake made-up story. So seeing montages (long ones at that) that were numbered here, took me out of the screenplay. I was more focused on the “shot number” than the images themselves. With that said, Eric may be directing this or writing it for a director. In that case, maybe he wanted to know the specific shots he would have to get.

It’s Monday morning and the talk of the town is how a little movie about cancer kids beat Tom Cruise in the middle of Blockbuster Season. The little film that could (The Fault In Our Stars) grossed 48 million to Tommy Boy’s (Edge of Tomorrow) paltry 28 million. That’s not just a beating. That’s a slaughter. Twenty years ago – heck, even ten years ago – this never would’ve happened. So why is it happening now? Anybody who tells you they know for sure is a liar. And I don’t know either. But what’s so interesting about this particular battle is that there are a ton of factors involved. And they’re all so damn juicy that I can’t wait to get to them!

1) Is Tom Cruise a movie star anymore?

If you’re going to put your money on one horse for Tomorrow’s lackluster showing, it’s probably that Cruise isn’t a movie star anymore. His last three films (Oblivion, Jack Reacher, Rock of Ages) failed to hit 100 million here in the States. Whether this has to do with Cruise getting older, Cruise going through his crazy streak, or people just losing interest in the actor isn’t clear. But it’s looking like his glory days are over. The question is, is this representative of a much larger trend?

2) Is the movie star dead?

As people stood on the hilltops and claimed the death of the movie star these last few years, I didn’t buy it. But a look at this year’s crop of summer films says otherwise. From X-Men to Godzilla to Spider-Man 2 to Rise of the Apes. The star in all these movies is the property. The owners of these properties then plug in the casting holes with whomever they deem worthy. You’re seeing less and less movies being made like Die Hard, where the star’s the star. With that being said, this is mostly (at least for now) a symptom of the summer season. As we get into the last quarter of the year and ACTING is actually required to make the movie good, movie stars are needed. How long that lasts, we will have to see.

3) Was the concept too weird?

Even though I loved the script for Tomorrow, the one thing I worried about was whether a mass audience would buy into the concept. I get nervous when you mash two big ideas into a single film, because, typically, audiences will only buy into one. They can accept aliens invading. They can accept time-travel. But can they accept an alien time-travel movie? I’m still not sure.

4) The title sucked.

I don’t talk about movie titles much because it’s one of the most objective parts of the business. But if Hollywood isn’t given a property that already has a name, they almost always fuck it up. “Edge of Tomorrow??” What the hell does that even mean?? It’s the most generic title ever and reeks of compromise. Edge of Tomorrow dudes, let me help you out here. When you have a property that nobody knows about and you’re trying to compete against properties (X-Men, Spider-Man) that have been around for decades?? You don’t want a title that’s going to make you MORE invisible. You have to take a chance and use something that stands out. The script’s original title, “All You Need Is Kill,” would’ve been so much better. It’s way edgier, and probably would’ve brought in more of the key demo you wanted – teenagers.

5) Does this fuck things up even further for spec writers?

While “All You Need is Kill” was based on a graphic novel, for the most part, it was a spec script. Nobody knew about the graphic novel. And it was written on spec (and sold for a million bucks). With the failures of high-profile specs this year like Transcendence, Draft Day and now, to a lesser extent, Edge of Tomorrow, is Hollywood going to be further terrified of betting on non-IP? Also, if the movie star system is dead, what are screenwriters supposed to write about now? It used to be, write a male lead inside a marketable genre. If that’s gone, and the studios are only dealing with high-profile IP anyway, then what’s the strategy of the average screenwriter? Should he even write original material anymore? Will it be like TV used to be, where you write a spec episode of your favorite show? So writers would write a feature in a long-standing franchise, like X-Men or Batman, in order to break in? Probably not, but it’s not clear where this is going yet. So we’ll need time to figure it out.

6) Did Fault really win the weekend?

Ah-ha, now we get to the part of the box office that the media still hasn’t figured out yet. Fault did beat Tomorrow at the domestic box office, but it’s not going to come anywhere NEAR Tomorrow internationally. Tomorrow has already racked up 80 million dollars internationally, putting it at 110 worldwide. When it’s all said and done, it should make close to 300 million. Fault will be lucky to make half that. The thing is, for the last 20 years, the media has put so much focus on domestic, they still think that’s the race to talk about. They understand that race. But movies make more overseas now than they do at home. Sometimes a hell of a lot more. But how do you write that definitive worldwide box office column when one of the key movies hasn’t even hit all of the available territories? It’s kind of a confusing byline (“Edge of Tomorrow maybe won the world box office this weekend…as it was in 65% of the territories but hasn’t hit the major European circuit yet and still hasn’t bowed in Peru, where Tom Cruise is enormous” doesn’t have the same ring to it as “Shailene takes down Tom!”). Since the domestic box office is definitive, I’m guessing they’ll continue to use it in stories. But at some point, this has to change.

7) People still read?

Probably one of the most confusing things about the modern-day box office is this whole reading thing. Studio heads, executives and producers claim the sky is falling because young people don’t want to spend two hours to see movies anymore when they can play on the internet, watch all that awesome TV, and play video games. It sure sounds logical, except that one of Hollywood’s biggest sources of income over the last 15 years has been book series adaptations. Harry Potter, Twilight, Hunger Games, Divergent, now Fault in our Stars. Movies are becoming antiquated but people still have time to engross themselves in a 2000 year old medium for 10 hours a story? Clearly, if people are spending that much time reading to the tune of adding billions of dollars to the box office, producers can’t bitch that it’s getting too hard to compete for people’s time.

8) Cancer curse.

Hollywood is TERRIFIED of cancer. People don’t want to be reminded of death when they go to the movies. They generally want to be happy. They want to be reminded of why life’s awesome. So how did Fault in Our Stars overcome that prejudice? Well, partly because it IS a movie about life’s awesomeness. The characters here have a lot of fun together. It goes to some dark places, but for the most part, there’s lots of positive energy here. The reason it beat the curse though is because it’s a really well-told story. It’s got a nice narrative drive (with the Amsterdam goal) and the characters rarely do or say the obvious thing, which gave it a fresh feel. The thing is, it was able to prove this in book form first, so people already knew it was good. I’d go so far as to say this wouldn’t have made 10 million opening weekend if it wasn’t a book first. I’ll say this though. I’ve never seen a movie this aggressively market itself as a cancer flick and do so well.

9) Tomorrow is good!

The big tragedy here is that Edge of Tomorrow is a really good movie! Not that I can say that myself yet (I was home sick all weekend), but a dozen site readers e-mailed me to say it was awesome, some going so far as to say it was the best movie they’ve seen all year. Usually, when a movie’s good, even if it doesn’t open well, it’ll make up for it with a long healthy run. But Edge of Tomorrow is planted right smack dab in the middle of the Summer Season, where even monstrous movies can disappear on their second weekend. Then again, it’s only real demographic competition the next two weeks is 22 Jump Street and Jersey Boys, and neither of those films directly crosses over with Tomorrow. So let’s hope that word-of-mouth spreads and the movie rebounds. If not, it might be the fault in Tom Cruise’s star.