Search Results for: F word

Guess what day it is?

It’s SCRIPTSHADOW WRITE A COMEDY SCRIPT IN 3 MONTHS BEGINNING OF WEEK LIST OF THINGS FOR YOU TO DO THIS WEEK day.

For those unfamiliar, Comedy Showdown is going down June 17th. That’s the submission deadline. In the meantime, I’m helping you write your script. I’ve already done Week One here and Week Two here. But even if you didn’t know about this until now, there’s still plenty of time to write a script. You’ll just need to up your pages-per-day. At the moment, I’m asking for 3 and a half pages a day. You might have to up that to 5 pages. Or, if you’re okay with not doing a final polish on your script, you can stay at 3 and a half pages.

Now, a little structure talk here so you understand what we’re going to be doing over the course of this week. For starters, we’re structuring our comedy assuming it’ll be 100 pages long. For our first draft, we are writing 1/4 of our script a week. Last week we wrote the first quarter (pages 1-25). Now we’re going to write the second quarter (pages 26-50).

This will take us to the script’s halfway point.

To make things easier for you, we’re going to be using the Sequence Approach and dividing this quarter into TWO SEQUENCES, each of them 12 and a half pages long. The first of those (pages 26 – 37.5) is commonly known as the “Fun and Games” sequence and is, arguably, the whole reason your came up with your idea. This is the section where you aggressively deliver on the promise of your premise.

Think about that first moment when the guys woke up in The Hangover. There’s a baby. There’s a tiger. Someone’s missing teeth. Those next 12 and a half pages delivered on the promise of the premise of waking up after a crazy night out and having no idea what happened the night before.

Or take Coming To America (the original). This is the moment where Prince Akeem and Semmi show up in Queens for the first time. You got the crazy New York cab driver who speaks his mind. The guys finding out that “Queens” is nothing like it sounds. Trying to get an apartment in New York for the first time. You are literally leaning into all of the funniest gags you can come up with from two guys who have never been to America… coming to America.

In other words, this should be the most fun you have the entire script. If you’re not laughing as you come up with fun new scenes for this section, you probably picked a lousy idea.

Where things get tough is in this second of the two sequences you’ll be writing this week (pages 37.5 to 50). This section isn’t as clear. In fact, I don’t know if anyone in screenwriting history has given it a name yet (feel free to suggest a name in the comments). But the good news is you know the exact number of pages it has to be – 12 and a half – which isn’t that many. And you know exactly where this sequence ends – it ends at your screenplay’s midpoint. Which means you can write towards your big midpoint moment.

The midpoint of a script tends to be the time where something big happens. That thing could be negative or positive. As long as it’s A BIG DEAL. It should also, preferably, alter the script in some way whereby the second half of the movie doesn’t feel exactly like the first half. This is a common newbie mistake. New screenwriters make the same jokes for 100 pages. You need something that alters the plot so that the jokes (and story) feel different.

I recently rewatched “Spy,” and the midpoint of that script is a positive one. It’s the moment where our spy, Susan Cooper (Melissa McCarthy), finally befriends target Rayna Bayanov, while having to maintain her cover. The entire first half of the movie was built around Susan trying to get to Rayna. In the second half of the movie, she befriends her, but must keep her cover. That change creates a whole new set of plotlines and jokes.

In Guardians of the Galaxy, which is essentially a comedy, the midpoint is a negative one. Peter Quill and his team lose the orb to big baddie, Ronan. This, of course, sets the stage for the second half of the script, which will require our misfit team to retrieve the orb before the bad guys activate it, destroying the universe.

During both of these sections, I want you to be focusing on two things. One, keep throwing obstacles at your hero. Especially in the second sequence. The first sequence – our “Fun and Games” section – is more about having fun with the concept. But having fun is often about throwing things at your hero that they have to deal with. So you’re going to pepper some of that in there as well.

Once out of the Fun and Games section, you’re in slightly more ‘serious’ territory. So you’re going to ramp up the obstacles. For example, in “Spy,” you’re going to throw an assassin at Melissa McCarthy. You’re going to blow her cover when she’s in the middle of a difficult task. Think of yourself as the “Obstacle God.” Your job is to create obstacles that you then drop into your film.

Comedy is often about being as shitty as possible to your hero and watching them squirm. That’s where the fun is! If you aren’t challenging your hero consistently, there isn’t going to be a lot of opportunity for laughs. If you find yourself writing dialogue scenes where you’re desperately looking for the next joke between two characters, chances are you’re not throwing anything at them. You’re leaving them to blow aimlessly in the wind – and that’s where comedy dies. When you throw obstacles at your hero, you don’t have to look for laughs. The laughs organically come to your heroes as they swat away all the shit you’re throwing at them.

The second thing I want you to focus on is reminding the reader what your hero’s flaw is. You do this by continuing to give them opportunities to overcome their flaw only for them to not be up to the task yet. Obviously, if they were up to the task, your movie would be over.

Look at Steve Carrel’s character in The 40 Year Old Virgin. His flaw was arrested development. He’s still stuck in his childhood, which explains why he hasn’t had sex yet. As a writer, you want to challenge that flaw to remind the audience what it is your hero has to overcome. In this case, Steve Carrel’s girlfriend suggests he sell his valuable childhood action figures to start his dream business. Carrel resists this, at first, to let the audience know he’s not ready. He hasn’t overcome his flaw yet.

If you don’t occasionally remind the audience of this over the course of your screenplay, then, at the end, when you try and write your big heartstrings-tugging moment, there ain’t gonna be any tears. And you’re going to ask people, “Why aren’t you crying?” And they’re going to say, “Because that whole ‘he’s finally ready to grow up’ moment came out of nowhere!” “Came out of nowhere” is code for you didn’t set it up properly. Which is why you need to keep reminding your reader that your hero hasn’t overcome his flaw yet.

One last thing. Don’t worry if your page count is a little long. If it feels like you’re going to hit 120 pages instead of 100, that’s okay. I’ve found that, in comedies, there are always going to be a few characters you don’t “get” the first time around. You’re trying to find where their ‘funny’ is in that first draft. And the best way to do that is to let some scenes run long so that your ‘trouble’ character gets a chance to find his voice. That might even mean changing him in the middle of the script because he wasn’t working in the first half. In the end, the biggest thing you’re going to be graded on is, “Is this funny?” So if characters aren’t working, you need to play with them and give them opportunities to let go. Sometimes it’s a single line you write that helps you finally ‘get’ a character.

Wow, at the end of this week we’re going to be halfway through our script! Who said writing a screenplay was hard?

Onwards and upwards!

Writing great comedy scripts does not come down to plot or theme or even, as commonly assumed, dialogue. It comes down to how funny the key characters are in the script. Are they constructed in such a way that they are inherently funny without having to do anything?

When you manage to construct an inherently funny character, it is magic fairy dust for your screenplay. You don’t have to think of funny things for them to say or do. They just say and do them. Contrast this with weak comedy characters who you always seem to be moving mountains for to get just one funny line out of them. Get the character right AND HE BECOMES THE COMEDY.

What we’re doing today is listing ten great comedic roles and you’ll see pretty quickly that there’s overlap. In other words, pay attention to the kinds of characters who become iconic because their DNA on ‘how to write funny’ is right there for the taking if you want it.

Here we go!

Alan in The Hangover – Alan’s primary characteristic is that he’s the most socially unaware person in the world. Combine this with a character who likes to talk a lot and you get someone who’s always going to be saying funny things. This is a comedy staple. You saw it with Dwight in The Office. You saw it with Kramer in Seinfeld. There are variations here on how goofy you want to get with these characters. But socially unaware characters who like to blast their opinions on everything consistently become some of the funniest characters out there.

Walter from The Big Lebowski – Aggressive. Mentally unstable. Paranoid. Note the extremes of the adjectives we use to describe Walter. He’s not “kind,” or “sweet,” or “pleasant.” He’s AGGRESSIVE. He’s PARANOID! Big exaggerated negative traits are great for comedy. We also have a character, like Alan, who loves to talk! Characters who express what’s on their mind have more ‘funny potential’ than characters who keep to themselves.

Derek from Zoolander – Derek is really really really really really really really dumb. Again, note the EXTREME here. Extreme works well in comedy. If Derek is only sort of dumb, there aren’t as many laughs. Also, Derek plays into a stereotype – that all models are dumb. While everyone is freaked out about stereotyping these days, it’s one of the best ways to construct a funny character. For example, if they made Zoolander today, it would not be controversial. Find that stereotype and play it up!

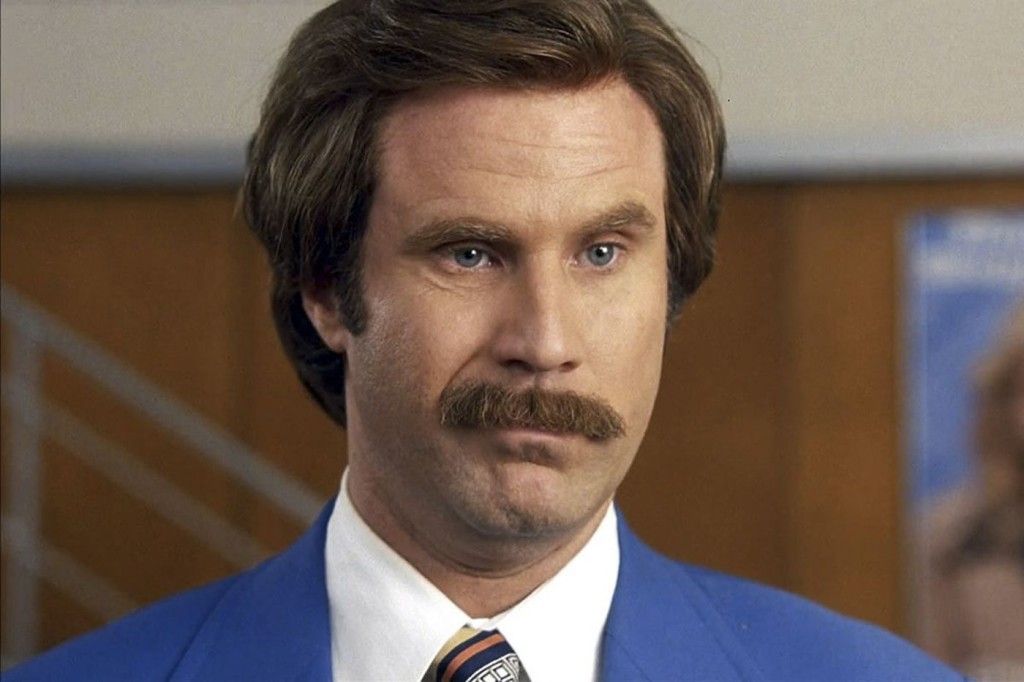

Ron Burgandy in Anchorman – His name is Ron Burgandy? Ron Burgandy exhibits another staple for hilarious characters. He’s clueless. The guy has no idea what’s going on around him is usually funny. But where you get those big laughs from Ron Burgandy is that he thinks he’s amazing. That’s always a great combination to play with in comedy. You take a negative and you contrast it with a positive. This guy’s so clueless. And yet, if you asked him, he’d tell you he’s the second coming of Christ. That gap between who he is and who he thinks he is is where all the laughs are.

Megan from Bridesmaids – Melissa McCarthy stole Bridesmaids with this character and she has the writers to thank for it. Megan is your classic “no filter” character. Comedy LOOOOOOOVVVES no filter. An additional note with this character. The temptation is to look for her laughs from dialogue. Don’t limit yourself. Extend the ‘no filter’ mindset to that character’s actions as well. One of the funniest moments in Bridesmaids is when Megan steals nine puppies from the wedding party.

Stifler from American Pie – We’ve got our first villain! American Pie did something really genius with Stifler which is why he became the most memorable character of the franchise. He got it as much as he dished it out. He makes fun of everyone but gets peed on at the party. He cusses nerds out but ends up drinking a beer full of semen. He beats people up yet a nerd has sex with his mom. This supports my theory about contrast being the key to comedy. If Stifler is just a dick the entire time and never gets payback for it (until the last scene), we don’t experience any contrast in his character. It’s going from one extreme (a Stifler win) to the other (a Stifler loss) that keeps his character hilarious.

Happy Gilmore – Happy Gilmore plays with one of the simplest comedy types available: the angry dude. People who get insanely angry are funny. If Happy Gilmore is only kind of angry, his character doesn’t work. Instead, this is a guy who tries to beat up national treasure Bob Barker from The Price is Right (The Price is Wronnnng, bitch!). Comedy’s often about going one yard further than the audience expects you to go. Happy Gilmore has 30+ examples of that. And it’s a great approach to writing comedy in general. Think about where the reader expects you to go with the joke, and then take one yard further.

Vizzini from The Princess Bride – We’re adding a second villain to the list. Inconceivable! Vizzini is built around his outsized ego. This is another area where we find contrast. Vizzini is this tiny little man. Yet he has the biggest ego of anyone in the movie. It’s that contrast (or irony) that makes the character so fun. And, again, you see that comedy works well with extremes. Vizzini believes he’s the most intelligent person in the world. He believes everybody’s not just dumber than him, but WAY DUMBER than him. That’s where you want to be thinking with comedy. You want to go to those extremes.

Borat – Misguided confidence is one of the funniest traits you can play with. Why is Borat so confident? Why does he walk into every situation with such assuredness? That contrast between his extreme confidence and engaging with a country he knows nothing about is where all the fun is. Borat is not funny if he’s constantly doubting himself. He’s not funny if he’s depressed and uninterested in his surroundings. He’s funny because of his outsized confidence in a number of scenarios where there is no reason for him to be confident at all.

Stapler Guy in Office Space – I thought I’d put Stapler Guy in here because he’s so unlike any other character on this list. Most of these characters are loud and in your face. Stapler Guy is quiet and mumbles all the time. So why is he still funny? Mike Judge flipped the script on this. Most funny characters are built around what they put out into the world. Stifler and Ron Burgandy and Happy Gilmore – these are all people who throw their personalities into the world. Stapler Guy is the opposite. His entire persona is built around how the world treats him. Nobody respects him. That’s the joke. People keep kicking him and kicking him and kicking him. And I think that’s why he’s so funny, is that a lot of writers would start to feel bad about kicking someone so much. Mike Judge doesn’t. He just keeps kicking. And he adds this brilliant little twist whereby Stapler Guy tries to fight back but nobody can hear him because he’s a mumbler. Sometimes being RELENTLESSLY HORRIBLE to your character can make him hilarious.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: An action comedy wherein Benji Stone, a lovable but deeply unpopular sixteen year old, is pulled into an international assassination plot by his uncle, a retired undercover assassin charged with babysitting Benji for the weekend.

About: This script finished with 8 votes on this past Black List. The writer, Gabe Delahaye, has written a little bit for TV. Despite having a few feature scripts in development, he doesn’t have a feature credit yet.

Writer: Gabe Delahaye

Details: 115 pages

Err, remember when I said go write a John Wick comedy? I guess I wasn’t paying attention. Somebody already did that. And here it is!

Benji Stone is just a 16 year old Northern suburbs of Chicago dork who likes robotics. The guy’s sole objective is to get into MIT. Well, that’s his sole objective initially. Objectives are about to radically change for Benji in about 24 hours. But, meanwhile, he and his best friend, the super popular Lakshmi, need to decide if they’re going to a party tonight.

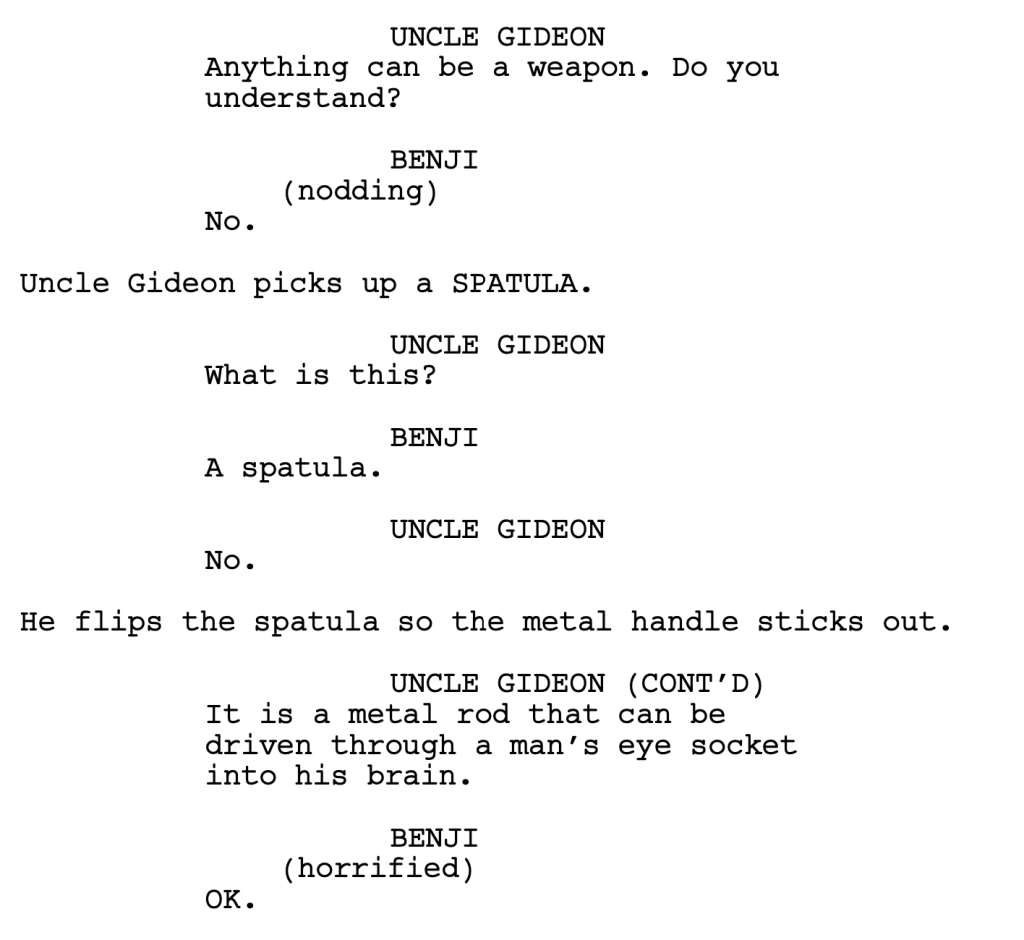

That decision is made for Benji, though, since his mom is going out of town and his uncle, Gideon, will be staying for the week, babysitting him. It turns out Gideon is kind of a nightmare. His questionable fashion choices (he wears a baby blue “Frozen” hat) are usurped only by his complete lack of humanity. The guy has the social graces of a Buckingham Palace guard.

Gideon makes Benji take him out to eat (Benji picks Denny’s) and that’s Benji’s first clue that something isn’t right here. Gideon drives a $300,000 McLaren. It is at Denny’s where some random guy comes up to their table, tells Gideon he looks like an old friend, and takes a picture of him. This odd moment is followed by Gideon walking into the parking lot and BEATING THE LIVING SHIT OUT OF THE GUY UNTIL HE’S DEAD!

Gideon comes clean to Benji. He’s an international assassin. A retired one. He’s been hiding out for years to convince the world that he’s dead. This was his first step towards trying to live a normal life. And now he’s back on “the board.” And, oh yeah, now that all the assassins know of Benji’s existence, it means that he’s on “the board” as well.

There are not many 16 year olds who can handle being told there’s a million dollar payday on their head and Benji sure isn’t one of them. He begins freaking out. But Gideon assures him that with a little training, he can make him a killer too. Uhhh, Benji says. I DON’T WANT TO BE A KILLER. But it’s too late for that.

Benji tries his best to ignore this horrifying new reality and goes back to school, starting with his driver’s ed test, a test that Gideon insists on joining. It’s a good thing he does. Cause in the middle of it, a group of motorcycle assassins attack them! Gideon leaps into the front seat but is forced to only control the gas and brake while Benji steers their way to a dozen near death crashes.

Benji remains in denial, going to school the next day. But he regrets it when their new “substitute teacher” has quite the strong Eastern European accent. Yes, she’s a killer too! And she attacks Benji! Gideon shows up just in time to take her out. But he informs Benji that the situation is dire. The woman he just killed is the sister of a major crime boss. If she showed up, he won’t be far behind. And this guy is the kind of killer that makes all these other killers look like mannequins. Both Gideon and Benji will be pushed to their limit!

Question #1: Does this pass the comedy concept test?

It does. The comedy concept test is, when you hear the idea, do you automatically think of a bunch of funny scenarios. “Uncle Wick” immediately makes you think of a bunch of funny scenarios. So, right off the bat, it’s looking good.

Question #2: Does this pass the comedy trailer test?

This is kind of like question 1 but it helps you get a better sense of if this is a movie or if it’s just a funny script. Try to imagine the trailer. Does it have a bunch of funny scenarios that will look great in a trailer? This does. The ‘John Wick joins the driver’s test” set piece was genius. Killing your nephew’s substitute teacher in the middle of school is also funny.

Question #3: Is the dialogue funny?

On this one, Uncle Wick is hit or miss. The dialogue is okay. But I would’ve preferred laughing out loud a lot more. A lot of the dialogue humor is built off of the relationship between Benji and his uncle. It’s Benji going crazy and his Uncle, who’s used to doing this stuff all the time, responding with dozens of variations of “What’s the big deal?” And these moments *are* funny. But I was hoping for some more wordplay. Funnier phrasing. Some more clever back-and-forth. It kind of kept hitting that same beat the whole time.

The script’s biggest weakness is that all the focus is put on Ben and the Uncle’s storyline – which is where the focus should be. That’s the concept. But it’s clear that Delahaye didn’t put nearly as much thought into Ben’s life. For example, Ben is described as the biggest nerd in school. Then, two pages later, we introduce his best friend, a girl who is the most popular girl in school.

Uhhhh, what????

We’re just expected to go with that? Um, no. That’s the kind of friendship that needs more explanation. And this continued throughout the school stuff. It was all rather thin. The bully had the lamest bully lines ever. Ben was trying to get the hottest girl in school to go to the dance with him.

It’s not that these things shouldn’t be used. They are high school movie staples. But they only work when you twist them slightly. So they feel a little unique. That uniqueness is what sets your high school script apart from everyone else’s.

Another issue with the script is the structure. Typically, in these movies, you go out on an adventure. A good example is The Spy Who Dumped Me. That movie sends its protagonists off on an adventure. And whenever your characters are on the move, it’s easier to structure, because the objectives are always destinations, and you can double those destinations up as major plot beats.

Here, they stay in town. And that presents challenges, which we see rearing their ugly head later in the script. For example, once we’ve established that there’s a million dollar price tag on Benji’s head, why is he going to school?

Clearly, the reason he’s going to school is so the writer can get in his Substitute Teacher Fight Set Piece. Which is great for them, but lazy for the storytelling. We needed a clearer time frame and goal for our heroes. Otherwise, you get your heroes waiting around for the bad guys to show up, and EVERYONE HERE knows how much I hate ‘waiting around’ plots. They cause way more trouble than they’re worth. You want your heroes to be active and driving the plot, not the other way around.

In the end, there’s enough juice in this comedy bottle to make it worth drinking. It’s not perfect but it was a welcome upgrade from the script that I started to read for today’s review – Black Mitzvah. Oy vey. Do NOT read that if you want to laugh.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: DRESSING UP DIALOGUE – You are writing a comedy, correct? So it doesn’t make sense for your characters to say things in a straightforward manner (unless that’s the kind of character they are). Early in the script, Benji’s friend knows something about Benji’s crush that can help him get her. So she tells him that. Now before I give you the sentence she uses to convey that, I want you to write your own version of what she says. Because, what you’re trying not to do is something like this: “Hey, I heard something about Heather that can help you.” That line is fine in a drama. But this is a comedy. So how can you dress that line up? Here’s what the friend actually says to Benji: “Speaking of something weighing on your conscience, if I give you a piece of Heather intel, promise not to let the police know I helped you plan her murder?” So much more creative. It’s not laugh out loud funny. But it gets a giggle. And that’s how you want to be thinking when you write your comedy dialogue lines. Dress them up.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) A depressed, progressive woman stuck in a conservative small Texas town starts micro-dosing the entire town with marijuana to make them all get along.

About: This script finished with 10 votes on last year’s Black List. Noga Pnueli has written one of my Top 25 scripts – time loop comedy, “Meet Cute.” So I’ve got high expectations today!

Writer: Noga Pnueli

Details: 112 pages

I think the above video best conveys how subjective comedy is. It’s one of the reasons I don’t review a lot of comedy scripts on the site. I always feel like the x-factor of whether I, personally, believe the writer is funny, gets in the way of me being able to accurately assess the script.

A comedy script can be perfectly executed in terms of structure, theme, and character. But if the comedy’s not my cup of tea, I’m still going to hate it. And things get even trickier when you’re trying to assess whether the writer’s not funny to you or not funny period. Because it would be nice if you could definitively say, “Comedy is not your strong suit. You should write in another genre.” But then someone would have to explain to me how people enjoy The Trevor Noah Show and Adam Sandler movies.

The good news is, I *KNOW* today’s writer is funny. She’s got a script in my Top 25 called “Meet Cute,” a time loop rom-com. So I know we’re going to get some mad comedy lessons. At least I hope so. When in doubt, place your faith in Noga Pnueli.

30-something Estee lives in Jacksboro, Texas. Estee is a “lifer.” That means you’re one of these people who gets stuck in the small shitty town you grew up in because you’re too afraid to leave.

But it’s even worse for Estee because she’s the only liberal in town. She works at a bakery where her boss won’t even bake a cake for a gay couple that comes in. This infuriates Estee so much that she gets in an argument with her boss and he fires her.

While stumbling through town hating life, Estee sees that Jacksboro just opened up their first marijuana dispensary. Estee’s never smoked pot in her life so she tries it out and “ohmmmmmmm,” all of a sudden she’s as relaxed and happy as she’s ever been.

So she gets an idea. She makes pot brownies and starts handing them out to people so that they can experience the same things she did. And they do. Which inspires her to make bigger batches of pot brownies. And then pot cookies. And then pot cakes. Which she delivers to everyone. Except, they don’t know they’re all being drugged.

Amazingly, when they figure it out, they’re not mad. They want her to continue low-key dosing them up. You see, as God-fearing Christians, they can’t be seen buying marijuana in town. This way, they get to to get high without the stigma.

When the pot store owner, who kind of has a crush on Estee, realizes what she’s doing, he informs her that he can no longer take part. Which means her entire operation of “Make Town Happy” will fall apart. Which means everyone will be angry and miserable again. Including Estee. So she has to figure out if there’s any last-minute substitute that can provide people with true happiness. What she ends up finding is the last thing she expects.

Initially, I liked High Society. When it comes to comedy, you want a writer who’s actually comedic. I know that sounds obvious. But you can tell a comedic writer by the way they write. For example, here’s an early excerpt from the script….

ESTEE, 30’s, is what is locally referred to as a LIFER, aka a woman who never left her pathetic hometown and whose wasted potential has made a home atop her shoulders like a ton of bricks.

She is currently avoiding her existential woes by baking complicated SOURDOUGH RYE BREAD in her kitchen.

Pay particular attention to that second sentence. Because there are thousands of ways you could’ve written it. You could’ve written, “Estee is currently baking bread.” “A miserable Estee shoves bread dough into her oven.” “Estee kneads the dough for some bread she’s making.”

You get the idea. These sentences convey the same thing Noga wrote. But they do so in a non-comedic manner.

The phrase, “is currently avoiding her existential woes” is a lot more clever, thoughtful, and funny, than simply saying, “is currently baking bread.” The word “complicated” is also relevant here. “Complicated” paints more of a picture for the reader than if the word wasn’t included. It creates a bit more of a comedic edge, particularly when you combine it with the phrase preceding it.

Funny phrasing and word choices, as long as they’re not overused, are a great way to “write funny.”

Unfortunately, despite Noga’s inherent comedic talent, she runs into the most common comedy problem of them all, which is that she doesn’t have a potent enough premise.

Comedic premises can be deceiving. They can seem funny. But a funny logline doesn’t mean you have 100 minutes of funny. It may only mean you have 30 minutes of funny. And the only way to learn this, unfortunately, is to write a handful of crappy comedies. Only through the process of failure do you get a feel for how long a comedic concept can last.

High Society is a 30 minute premise. How do I know this? Because it’s a South Park episode. They have a very similar episode on South Park. And even they struggled to get their concept to the 23 minute mark.

Why doesn’t this concept have legs? Well, we get to the part where everybody is consuming marijuana and chilled out before the midpoint of the script. So, then, what’s left? We’ve already achieved the funny part mentioned in the logline. What now?

The next plot development is: will the town realize they’re being drugged? Is this a funny development? I would argue it isn’t. There is some conflict involved because there are consequences to what Estee has done. So there’s a dramatic reason for us to keep reading. But I wouldn’t say there was any *comedic* reason for us to keep reading. The script isn’t presented in such a way where this reveal will be treated with a laugh.

Then, we finally get that reveal and guess what? Nobody has a problem with Estee doing this. In fact, they all like it. So, ummmmmm, where is the conflict in the movie? Estee literally has zero problems now. She’s drugging people. They like it. Why, exactly, are we still watching this movie? There’s nothing left to be resolved!

Noga seems to realize this so she comes up with this minor conflict whereby the marijuana shop owner says he’s not going to sell her pot anymore. But, at this point, I don’t care. Too much conflict has been sucked out of the story.

If there’s one thing to learn about comedy today, it’s that if you don’t take care of your plot, your comedy won’t matter. If your characters aren’t engaged in some level of compelling conflict that has genuine stakes attached, then we don’t care what happens to your characters. And people won’t laugh if they don’t care what happens to your characters.

I don’t even know what Estee wants in this movie. Why is she even doing any of this? It’s an important question because, if we don’t know, then we don’t know why it’s so important for her to succeed. And without a need to succeed, there are no stakes. The guys in The Hangover cannot, under any circumstances, lose their friend eight hours before his wedding. The stakes are so high that we’re extremely engaged in their mission.

Not so with this one. I get that it’s pot comedy and that this type of comedy is a little more chill. But I’ve seen pot comedies with high stakes and lots of activity (Pineapple Express). So while I’ll give High Society a puff. I’m not giving it a pass.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Make sure that your comedy concept provides stakes that will last 100 minutes. I see too many comedy writers who dive into a comedy script with stakes that get you to page 40. And then they spend the rest of the movie flailing about trying to be funny. This is important, so pay attention. Characters are the most funny when they have something to lose. Therefore, if it’s muddy or unclear what your characters have to lose, chances are, nobody’s laughing. I wasn’t ever clear what Estee had to lose in this movie.

Oh man, going through these loglines was equal parts awesome, frustrating, flabbergasting, and hilarious. One of my biggest laughs happened when I read this logline: “The search for a cure lands a doctor and her terminally ill husband alone on a boat, in a fight for their lives when the ‘super steroid pills’ intended for him are eaten by a plague of rabid, starving RATS.” For some reason, I misread “super steroid pills” as “sexual enhancement pills.” The movie I was imagining in that moment was unlike any movie I’ve seen before.

There were a ton of ‘ALMOST’ loglines. At their core, they were high concept. But something about the way they read indicated they weren’t quite where they needed to be. For example, here’s one that almost made it – “A disgraced bomb disposal expert struggles to escape the mind games of whoever trapped him inside a mascot suit and an explosive vest in New York Times Square.” I loved the irony of this setup. But I don’t know if this leans into the level of seriousness implied by the situation if our hero is in a mascot suit the whole time.

I want to thank everyone for submitting. I wanted to included every submission, of course, but there were only six slots (I had to add one more!) available. I’m sure many of you believe your concept is better than these. It very well might be. There’s always an element of subjectivity to this. For that reason, feel free to pitch your logline in the comments section. We’ll see if the other readers agree. Also, next Thursday, I’m doing a “Why Your Submission Didn’t Make It” article for five entries. If you would like your entry to be on that list, let me know in the comments. The goal of these articles is always to help the writer understand how to write better loglines and better submissions. So it’s very helpful.

If you have never played Amateur Showdown before, five scripts compete against each other below. Read as much of each script as possible and vote for your favorite in the comments. Votes close Sunday night at 11:59pm Pacific Time. The winner will get a review on the site next week.

Want to compete in a future Amateur Showdown? I have good news for you. I will be announcing the next Amateur Showdown Category MONDAY. So be ready for that!

And now, it’s time for the FIVE – MAKE THAT SIX! – CHOSEN ONES TO COMPETE.

Congratulations if you made the cut. And good luck to all!

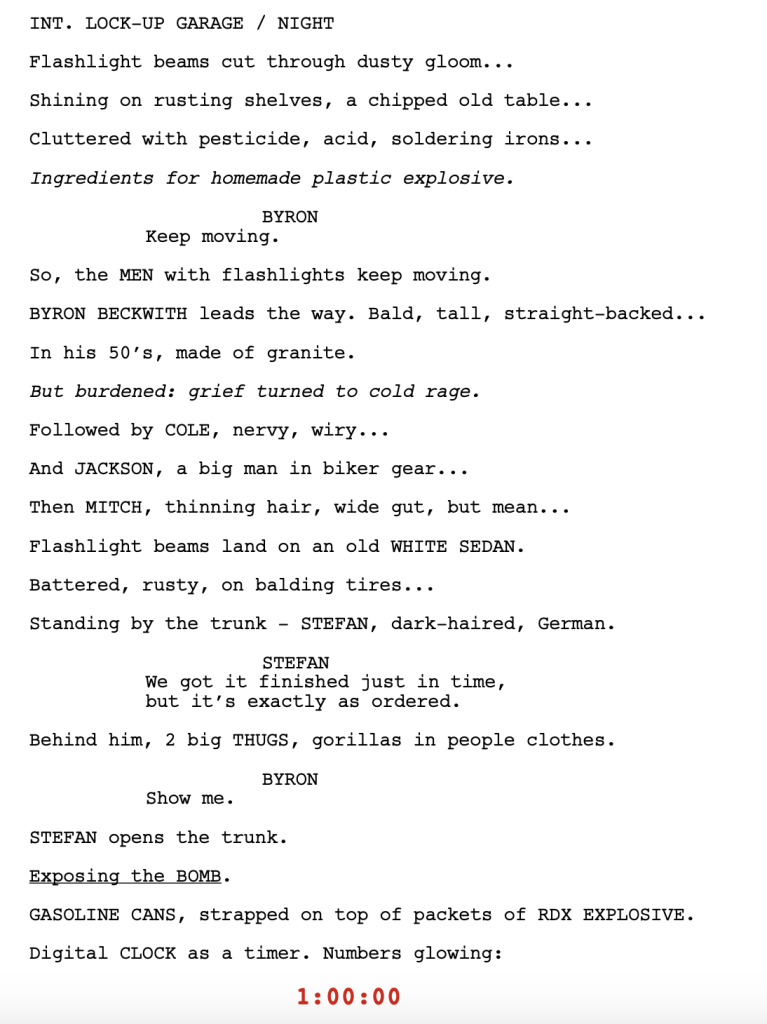

Title: BLAST RADIUS

Genre: ACTION THRILLER

Logline: A desperate man fleeing a failed robbery carjacks an old Sedan and speeds away, only to realize he’s now driving a car bomb, and it’s ticking…

Why You Should Read: I’ve tried to write the ultimate GSU movie. I’ve written it in a VERY terse style, trying to tell the story with as few words as possible, so (I hope) the script will read as fast as the movie is designed to play.

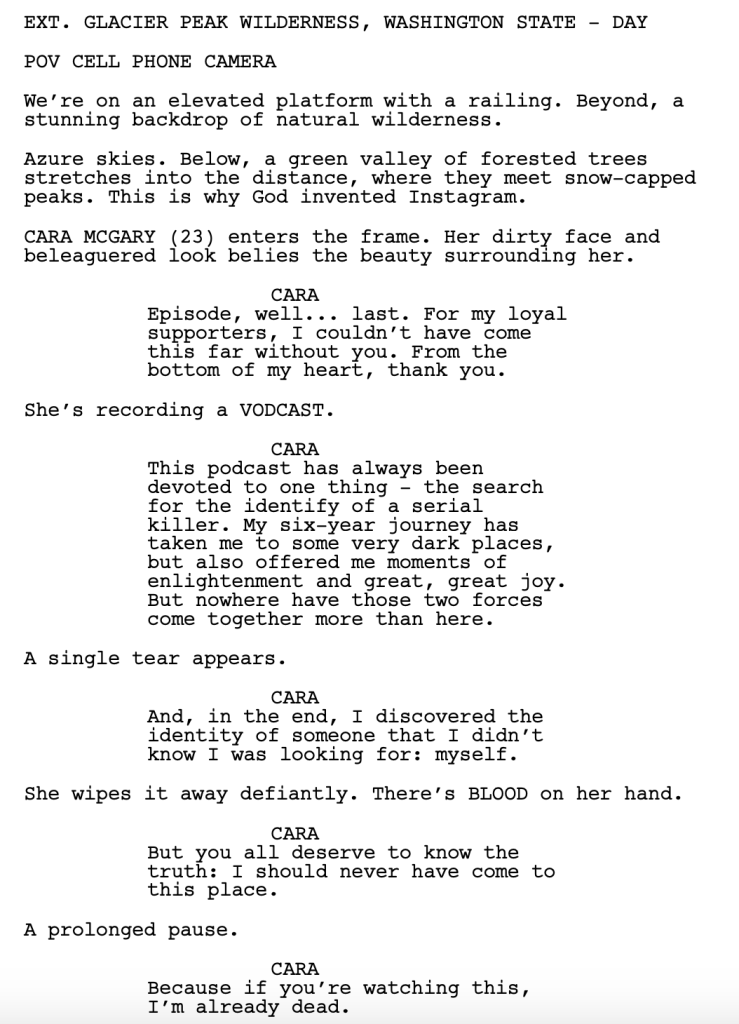

Title: The Watchtower

Genre: Contained Thriller

Logline: An amateur true-crime podcaster takes a job manning an isolated fire watchtower in a remote wilderness area, where she’s convinced a series of recent disappearances is the work of a serial killer. Her investigation is turned upside down when she’s forced to take in an injured hiker – a man she suspects may be the killer she’s been obsessed with finding.

Why You Should Read: Big concept on a small budget. True-crime podcasters are the Clarice Starlings of today. And, in our pandemic world, thousands are heading to the great outdoors to find our “safe place”. Essentially a two-hander, this thriller is set in the unique world of fire-tower lookouts, otherwise known as “freaks on the peaks” – where the extreme isolation is known to bring out the best – and darkest – side of any personality. It’s a story about the duality of human nature.

In the wilderness, there’s no place to hide from yourself.

Title: Nine Lives, or The Infallible Guide to Extracting Revenge on Your Enemies

Genre: Dark Comedy/Drama

Logline: After getting hit in the head, a bipolar man starts collecting an army of cats at the behest of his dead childhood cat’s spirit to get revenge on those who’ve wronged him.

Why You Should Read: I know “high concept” is a bit nebulous for most, but in my mind, the main component that a high concept film needs is an elevator pitch that immediately marks it as something distinct, (even within its own genre) so people hear it and are compelled to see how things unfold for themselves. — My script doesn’t have any time travel or big reveals; it just takes an unusual but honest setup of a man and follows the path of the story, hopefully delivering a tight, well-contained character study with the backdrop of craziness (literally and figuratively) and several “did he really just do that?” type moments carrying it beyond a run-of-the-mill character piece.

Title: HAG

Genre: Horror

Logline: A woman suffering from night terrors seeks treatment at a sleep disorder clinic, only to discover that the shadowy creature tormenting her is real… and it will never stop until it steals away her breath.

Why You Should Read: Dealing with ‘Old Hag Syndrome’ (a state of paralysis where the sleeper awakens completely frozen but conscious, convinced a supernatural entity is sitting on their chest), this script introduces us to the Hag: a malevolent, body-distorting embodiment of nightmares that will surely go on to become a new movie monster franchise. The story mixes horror with psychological drama and creepy creature action. Set in a clinic on an island, featuring a small cast, this is a contained horror script that boasts a memorable, crowd-pleasing monster that will still be economical to shoot!

Title: MAELSTROM

Genre: Black Comedy/Thriller

Logline: When a freak storm hits a couples therapy retreat and turns all men in its path into predatory killers, a devoted wife and her new female allies must fight to save their lives, as well as their relationships.

Why You Should Read: MAELSTROM is a satirical contained thriller that takes the idea that the weather has the power to negatively affect our behaviour and amplifies it to 11. But what if we took it one step further still? What if it only affected male behaviour? And what if the affected men’s behaviour sorta, kinda, a teeny bit mirrored the behaviour displayed by asshole men the world over, resulting in a social commentary that explored themes of self-love and emotional independence in a battle royale of the sexes? Welcome… to MAELSTROM.

Title: Dinosaurs on the Beach

Genre: Comedy / Adventure

Logline: After discovering a living baby T-Rex, a failed paleontologist decides to evade the corrupt local authorities and raise the dinosaur himself. Jurassic Park meets E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.

Why You Should Read: You like Jurassic Park. You like E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial. Why shouldn’t you read this?