Search Results for: F word

Going back through Tuesday’s and Wednesday’s script reviews, I identified a common theme, which was: HOLY SCHNIKEYS, STRUCTURE MATTERS A LOT!

Without structure, you can lose your grip on a good concept by page 20. I actually like the concept of a smart house attacking someone. I know it’s been done before but no one has come up with the definitive version yet. Which means it’s out there for the taking.

But the lazy structuring killed that script.

And a sex VR unit that gets in between the friendship of two couples is also a good idea. Done well, it could be a modern day Sex, Lies, and Videotape.

But the nonexistent structuring killed that script.

So what went wrong? Let’s dive a little deeper.

With “An Aftermath,” a script about a woman whose controlling dead husband lives on in her smart home’s AI, the writer didn’t move the plot along fast enough. For example, it took until page 80 until the house did something even mildly harmful (locking a guest in a freezer).

With “Blur,” about a group of 20-somethings whose lives become entangled after a Sex VR system enters their lives, there was no structure at all because there was no plot. Characters didn’t have anything to do, which left many scenes hanging in the wind, looking for a reason to exist.

Since structure is synonymous with plotting, we can identify part of the problem by looking at the definition of “plot.”

Here’s Wikipedia definition: In a literary work, film, story or other narrative, the plot is the sequence of events where each affects the next one through the principle of cause-and-effect. The causal events of a plot can be thought of as a series of events linked by the connector “and so”.

Ugh. That definition is an enabler for boringness. It’s basically saying that as long as things keep happening one after another, and that they’re connected in even the vaguest way, you’ve properly “plotted” your film. Which is actually what got this week’s scripts into trouble.

When it comes to movies, you want to think of plot as “a character trying to achieve an objective who then must overcome a series of obstacles along the way.”

Almost every good movie follows this model.

It does get tricky in certain situations and if you’re not versed in plotting, you may think some great movies are ‘structure-less’ because they don’t line up with this definition. But they usually do. The formula is just slightly tweaked.

In Shawshank Redemption, for example, Andy Dufrense spends the entire movie hanging out in a prison trying to live a happy life. Where’s the plot in that? Well, as it turns out, Andy Dufresne had a gigantic goal he was trying to accomplish. To escape. It just wasn’t revealed to us until the end.

Or then you have movies like Infinity War where the villain has the goal and all our superheroes are scrambling. That can be confusing since the traditional heroes aren’t the ones going after the primary objective. But the main thing to remember is that somebody wants something really badly and their quest to get that thing disturbs the environment in a way where they’re constantly encountering obstacles that may stop them.

If nobody’s moving anywhere, you can’t throw anything in front of them. That was Blur’s problem.

If characters *are* moving but you’re not throwing enough things at them, you get a script like An Aftermath.

Another reason writers struggle with plotting is because they don’t understand the three act structure. They understand it theoretically. But they don’t know how to put it into practice. Especially when you start having to meet certain page checkpoints. It can be a lot to manage when all you want to do is get your ideas down on the page.

So here’s a basic 2-rule hack to give your script structure. One, give your main character a goal they’re after. That’s imperative. And two, make something big happen every ten pages.

If you want to know a secret about how The Disciple Program was written, it was written during an interactive contest where the writers had to write ten pages at a time, then submit them for feedback before writing the next ten pages. What that did is it forced the writer to make something cool or exciting happen at the end of every ten pages. It basically ensured that the plot kept moving.

Or if you want to make it even simpler on yourself, HAVE BIG PLOT POINTS HAPPEN A LOT FASTER THAN YOU THINK YOU HAVE TO MAKE THEM HAPPEN. What I’ve found with beginner screenwriters in particular (but this can happen to any screenwriter) is that they believe their script is more interesting than it is. This gives them permission to allow their plot to unfold verrrrrrry slowwwwwwwwly. You need to constantly disrupt your story with new obstacles, new information, and new developments.

95% of screenplays are boring because they don’t follow this simple principle.

That would’ve helped “An Aftermath.” But Blur is a tougher case because it doesn’t fit into that neat structural box.

That’s because you have four protagonists instead of one. The reason this is a challenge is because it prevents you from doing the “Main character has a goal they go after” approach. How do you address this?

You do it by applying the same approach, but split up between four characters. That means each character should have a goal they’re trying to obtain during the story.

For one it might be getting into law school. For another it might be getting a job in the city they always dreamed of living in. For another it might be breaking up with their significant other, something they want to do but haven’t had the courage to do. These goals don’t have to be Avengers-level goals. They just have to be important in relation to the story you’re telling.

Once you give these characters goals, something magical happens. They’re now going to have places to be. They’re now going to have things to do. They’re now going to have more interesting things to talk about. You now have obstacles to throw at them because there’s finally something to throw an obstacle at (Character A gets admitted into law school but then is denied a student loan. They can’t afford school without that loan. What are they going to do?).

You may say, what does this have to do with a VR sex machine story, Carson? This is the beauty of adding purpose to your characters’ lives. You get to tell the exact same story you’re telling – these characters get intertwined with an addictive new sex technology – but it’s now happening inside a life that has more detail, has more interesting developments, has… well… HAS MORE SH#% GOING ON!

But most importantly, these new objectives in your characters’ lives provide the script with STRUCTURE. The reader now has a sense of where your characters want to be so they feel like we’re all on a purposeful journey together.

You need to provide the reader with a series of rewards along the way for them to feel satisfied. “If you read just a little bit longer,” you promise them, “you’ll get to find out if Jane convinced the bank to give her that student loan.” But if you don’t integrate these purposeful journeys for each of your characters, your script won’t have these rewards. And if we, the reader, aren’t being rewarded, we’re getting bored.

So yes. Character is important. Dialogue is important. Theme is important. But if your structure is limp, or worse, non-existent, none of that matters. So make sure your structure is on point.

Carson does feature screenplay consultations, TV Pilot Consultations, and logline consultations. Logline consultations go for $25 a piece or $40 for unlimited tweaking. You get a 1-10 rating, a 200-word evaluation, and a rewrite of the logline. They’re extremely popular so if you haven’t tried one out yet, I encourage you to give it a shot. If you’re interested in any consultation package, e-mail Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: CONSULTATION. Don’t start writing a script or sending a script out blind. Let Scriptshadow help you get it in shape first!

Just like you’re not a real comedian unless you’re looking for jokes in every situation you encounter, you’re not a real screenwriter unless you’re always looking for that next movie idea. That skill becomes even more important in times like these, when you know Hollywood is going to be hot on the Pandemic Express over the next few months, gobbling up the best pandemic ideas it can find.

Well I’m going to make sure that Scriptshadow readers are ahead of the game when it comes to pandemic-inspired concepts.

The trick is to not go with a literal interpretation of the idea. If your concept is, essentially, “2012,” but with a pandemic, nobody’s going to give you money for that. Anybody can come up with a literal interpretation of an idea.

If the news covers a missing plane story, like Malaysia Airlines Flight 370, writing a movie about a plane that flies out of Malaysia and disappears isn’t going to get you anywhere. By the time you pitch that idea, Hollywood will have already been pitched it ten times already. THAT DAY.

As writers, your job is to come up with THE ANGLE.

This is what good writers bring to the table. They exploit the hot subject matter via an angle that the average person isn’t creative enough to think of. Just like Michael Jordan’s turnaround jumper was the shot that made him the most valuable player in the league, your ability to come up with creative angles to common concepts is what will make you valuable.

That brings us to the deal that 21 Laps (Stranger Things) and Sight Unseen (Bad Education) just teamed up on.

They purchased the rights to a 2018 Medium article titled, “Survival of the Richest.” The article follows a futurist who travels around the world giving speeches about where the future is headed.

One day he flies out to what he believes will be another one of these conferences but when he gets to his hotel, he’s ushered into a private room and greeted by five billionaires. These billionaires want to get his opinion on where he sees the future going.

It makes sense. If you want to keep your billionaire status, you have to know where the markets are going in the future. Is oil still going to be important in 20 years? Or should I invest in hydrogen-powered cars? Except those weren’t the questions these billionaires were asking.

They were more interested in topics like, “If I own a compound in the apocalypse, how do I prevent my security team from turning on me when money is no longer worth anything?” The question turns out to be surprisingly complex, with no one able to come up with a good answer.

Unfortunately, the rest of the article reads like the author forgot what his point was, rambling on about well-tread topics such as whether robots will eventually replace humans in the work force. But when you’re looking for things to adapt, the concept is more important than the execution. That’s because a good screenwriter can take a good concept and run with it.

And the angle here is an intriguing one. It’s not about what you and I do when the resources run out. It’s about what Jeff Bezos and Mark Zuckerberg do. These are people who have built impenetrable capitalistic fortresses – the rest of the world desperately clinging to the jobs and products they offer.

But what happens when we no longer need their products or their jobs? What happens when a billion dollars holds less value than a pair of shoes? That’s a movie angle there.

But it isn’t everything and since Deadline’s announcement didn’t provide enough details on the pitch, we’re left to make some fun guesses as to which direction they might go in. The cool thing about this idea is you can go big or you can go small.

There’s a version of this where our futurist is flown out to a general meeting with a controversial billionaire at his remote home. He then learns he’s here to evaluate the billionaire’s compound to see if he’s properly prepared for the apocalypse.

The futurist eventually stumbles upon a giant secret – that the reason he’s being asked to secure this person’s apocaoypse defenses is because a network of billionaires is planning to incite the apocalypse then become the new global government. When our billionaire learns he’s onto him, our hero has to escape. This would be the low-budget “Ex Machina” version of the concept.

Or we can set things in the apocalypse. A billionaire gets word that a mob of 200 people is on its way to his compound. He has two hours to prepare for the onslaught, depending only on his small security team and high-tech defensive equipment (preferably technology that made him all his money in the real world). Sort of like a modern-day medieval castle takeover – barbarians at the gate.

Finally, we have a futurist who’s flown out to what he thinks will be a conference, only to end up at a remote South American billionaire’s home. He meets several billionaires who pose the same questions mentioned in the article.

They offer him a job. They’ve put together a “Stanford Prison” like experiment whereby they’ve hired several hundred people who are located several miles from a compound. Those people have one goal. Get into the compound and into the control room. Our futurist will consult our billionaires in real time on how to stop them.

However, he soon learns these volunteers have been offered a giant monetary reward for succeeding to ensure they will act as desperately as real people in the apocalypse, and that the preventive measures being used to stop them are deadly. This isn’t an experiment. It’s real.

Good concepts are like bountiful rivers. They offer all sorts of possibilities. It will be interesting to see which idea 21 Laps and Sight Unseen go with. What about you? Where would you take this idea?

Last month, we had Sci-Fi Showdown. The voting was too close to call so last week I reviewed one of the top vote getters. That script didn’t quite hit the mark for me and, as it happens, I’d read Nowhere Girl a long time ago and liked it. Since I wanted a script that celebrated all the hard work people put into submitting to Sci-Fi Showdown, I decided to review Nowhere Girl this week.

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: A remorseless killer is given the death penalty, only to wake up 1,000 years later in a spacecraft built for one, with an artificial conscience implanted into her nervous system and a life sentence to serve out.

Why You Should Read: I wanted to write a character who has no redeeming qualities whatsoever, the most horrible monster I could imagine, and still somehow make her worth rooting for. Since my wife is a schoolteacher, and I have received that dreaded text that her school is on active shooter lockdown a couple of times, I knew who that character would be. So now I’d love to know if my fellow writers think I pulled it off.

Writer: Chris Cobb

Details: 113 pages

When it comes to script-reading, the only thing that truly matters is, does the script stay with you?

I’ve read plenty of what I’d call “good” screenplays that people have later reminded me about and I had no idea what they’re talking about. On the flip side, I’ve read some scripts that I didn’t like at all but they’ve remained seared into my brain years later (Christy Hall’s, “Get Home Safe” for example).

I’ve come to the conclusion that if a script stays with you, good or bad, it has something going for it.

I read Nowhere Girl over a year ago as a consultation script and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it. It’s such a weird premise. It’s something that shouldn’t work at all. And yet it digs into you in a way other scripts don’t.

There were some issues with it but I don’t remember what those issues were so I’m excited to read this new draft and, hopefully, whatever problems I had with the script will have been solved. Let’s take a look!

We don’t meet 19 year old Sara under the best circumstances seeing as she’s mowing down anyone she sees at her university with a sub-automatic machine gun. After Sara kills a good chunk of people, a classmate of hers, Amber, pleads for her to stop the killing. She even offers to be Sara’s friend. But Sara wants none of it, gunning down Amber as well.

When a SWAT team rushes in, Sara tosses a bomb at them but it blows up too quickly, the blast hitting her. Cut to months later as a disfigured Sara informs a courtroom that she wants the death sentence. A year later, she gets her wish to die.

Only to wake up in a strange room. Sara learns that she’s on a spaceship far far away from earth. Andrew, an A.I. chip inside of Sara, explains what’s going on. It’s been one thousand years since that fateful day and her job is now to help facilitate an intricate bot delivery system (they drop off bots to bigger bots which then deliver those bots to planets or outposts) in the middle of nowhere.

As time goes on, Sara learns how the system works. She must routinely report to her local outpost (to a man named “The Warden”) and assure him that all systems are running smoothly, while managing the biggest threat to the ship, ion storms, each of which have the capacity to destroy her.

Just as Sara is starting to get the hang of things, Andrew takes on the identity of a familiar voice. It’s Amber, the girl who tried to stop her that fateful day. Sara finds herself drawn to Amber, ultimately befriending her. But when the Warden threatens to shut Amber off forever, Sara will do anything to save the girl whose life she took.

Let me start off by saying I’m a big fan of this script (in case I didn’t already make that clear).

It’s so bold. It’s so unexpected. It’s so different.

You’re not going to have a script experience like Nowhere Girl anytime soon.

I also put a premium on scripts that don’t go where I think they’re going to go. I love turning the page and having no idea what comes next. That’s Nowhere Girl in a nutshell. I mean how do you predict a story that starts off with a teenage female school shooter who then ends up on a ship a thousand years in the future? It’s just such an odd cool setup.

Ironically, Nowhere Girl’s biggest strength is also its biggest weakness. The reason you don’t know where it’s going is because there’s not a lot of structure. Neither Sara nor Andrew have a clear goal. That allows Chris to take the story in a lot of different directions. But it also risks those directions feeling pointless and unfocused.

A loose plot is fine if the character development is stellar but when it comes to Nowhere Girl, it felt like we were always flirting with good character development but never quite getting there. That’s because I don’t know what flaw Sara is trying to overcome and I’m not sure how Amber solves that flaw.

We know Sara doesn’t feel anything. She’s been diagnosed a psychopath. Andrew later shows Sara a replay of the shooting but forces her to feel what Amber felt during the exchange. This allows Sara to feel for the first time but the second the experience is over, Andrew erases the feeling so Sara is back to normal.

In other words, Sara learns how to feel in the first third of the movie. So doesn’t that mean she’s overcome her flaw? She’s learned what feeling is? Or was that meant to warn her up to the sensation of feeling? The real lessons are ahead of her. I’m not entirely sure.

Then when Amber replaces Andrew, she literally becomes Sara’s conscience. Amber actually says that (“I’m your conscience.”). That means that she’s not Amber. She’s Sara’s conscience. So as Sara and Amber build their friendship over the course of the second act, it would seem we’re further exploring the character arc of Sara being able to “feel.” Except we’re not. Because the person she’s befriending isn’t Amber. It’s her own conscience.

I don’t know. It was confusing. No matter how many times I tried to make sense of it in my head, it didn’t work. It seems like Chris is overcomplicating this. Maybe he can shed some light on what he was attempting to do so we can help him.

If you ask me, a better plot would be a good starting point. Plot equals structure and structure helps dictate where your characters need to go, both internally and externally.

You have these remote delivery vessels scattered throughout the sector to play with. And we know about these outposts where there are physical human beings. If Sara and Amber could get to a delivery vessel which, in turn, could get them to an outpost, with the ultimate plan being to escape or convince the bureaucrats to let them go, that could give you the strong goal this story needs.

I could imagine an ending where Sara gets to the outpost, is escaping in the halls, guns at her side, being pursued by others. And she essentially has the same choice she had at the beginning of the story. She can kill or she can stand down. And this time she chooses to stand down.

Another option is that maybe the goal is rehabilitation, plain and simple. Sara has two jobs. Job 1 is to perform the deliveries. Job 2 is she has to do her rehabilitation exercises for hours every day, which amount to Andrew helping her learn how to feel. That will be done through reliving certain life experiences. And it will also be providing lessons that challenge one to to feel emotion. At the end of a certain time period, she will get an audience with the Warden to prove she’s changed. If she has, she wins back her freedom. If she hasn’t, she’s got to wait another (5? 10? 30? years?) for her next chance.

Neither of these suggestions are perfect but the point is they provide structure. So if not them, find something else that can give this script a plot. Because it can’t be a character floating in space talking to herself the whole time. There has to be more to it.

With that said, Nowhere Girl was unlike anything I’ve ever read. There’s a movie in here somewhere and I think if we all gave Chris our suggestions, it would help him find that movie. Intrigued to hear what all of you thought cause I enjoyed this!

Script link: Nowhere Girl

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whenever I encounter a script issue, the best solution is usually the simplest one. So when I look at Nowhere Girl’s issue of Sara’s conscience being an AI chip inside her body who later takes on the form of Amber and it being confusing what Sara is really bonding with in her pursuit to change (befriending Amber or befriending her conscience) my solution is to massively simplify it. Why can’t Andrew be the ship’s AI? Not a chip inside Sara. He creates a digital replica of Amber and Sara must learn how to feel through the friendship she builds with this entity? That’s a lot simpler, isn’t it?

If you asked 100 of Hollywood’s top producers, directors, actors, and writers, who the hottest screenwriter in the world was at the moment, the majority of them would say Phoebe Waller Bridge.

Bridge is killing it all areas of screenwriting but the thing she’s best known for is her dialogue. It’s been a long time since we’ve had a screenwriter whose dialogue was this celebrated, so I thought, why don’t we break some of her dialogue down?

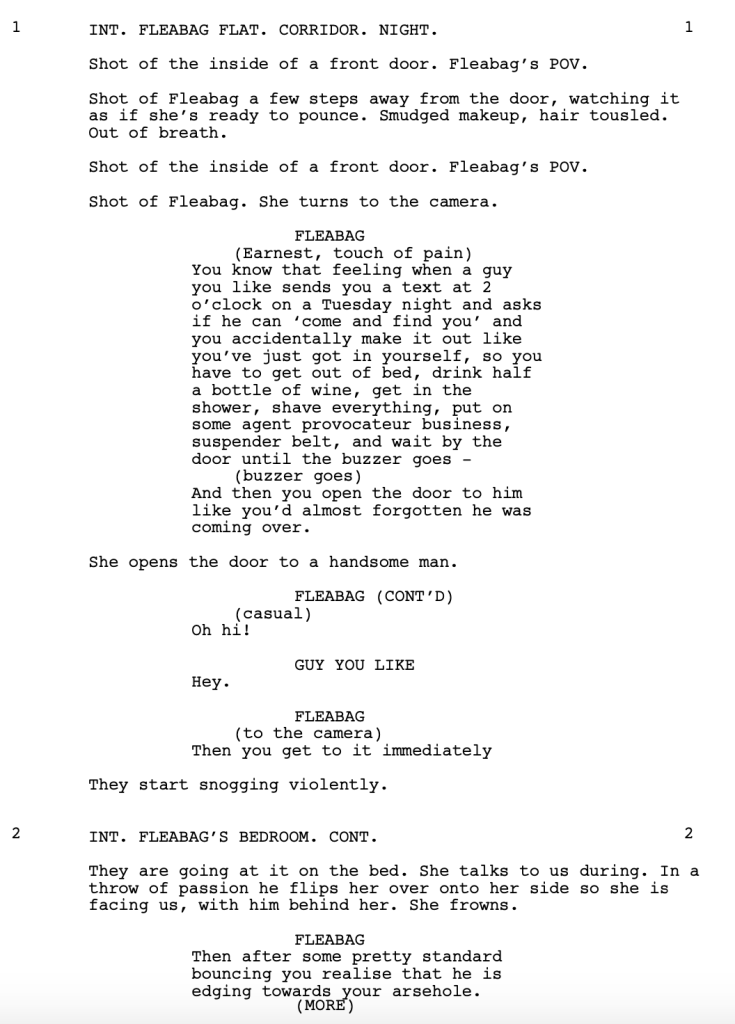

And what better scene to dissect than the opening scene of the Fleabag pilot. Do not worry if you’ve never seen the show. I’m going to include the pages here for you to read.

The first lesson for why this dialogue is so great is our most important one. Fleabag is a talker. She’s the definition of a dialogue-friendly character. One of the biggest mistakes writers make is they try and inject punchy dialogue onto characters who wouldn’t say those things. Imagine putting John Wick in this scene. He’s not going to give you anything close to what Fleabag is saying because John Wick operates with his gun, not his tongue.

So if you’re ever anxious about writing good dialogue in your script, the job starts long before you’ve written a word. You want to conceive of a primary character – it doesn’t have to be your hero but it does have to be a key charcter – who likes to talk or who says interesting things or who says controversial things or who’s clever or who’s funny or who’s weird or who talks first and thinks later. This decision will dictate 90% of the quality of your dialogue.

The next thing we’ve got going here is that Fleabag talks directly to the viewer. Now some people hate characters who do this. I get it. My feeling has always been, if you’re going to do something that ballsy, you better have the skills to back it up. There’s nothing worse than a “clever” character talking to the camera who’s a big fat ball of lame.

But assuming you’re good at breaking the 4th wall, doing so achieves a unique effect. It both breaks the monotony and it breaks up the predictability of the conversational flow. You’re no longer dependent on His Turn to Talk, Her Turn to Talk, His Turn to Talk, Her Turn to Talk.

This is why I’ll tell writers that just because Character A asks a question, that doesn’t mean Character B has to answer. They can say nothing and Character A can move on to the next line. At least that way, you’re breaking up SOME of the monotony of the conversation. But outside of a few other tricks, you’re relegated to His Turn, Her Turn, His Turn, Her Turn.

Once you throw this new option into the mix of your protagonist talking to a third person that the second character can’t see, that gives you a rare opportunity to do all sorts of creative things with the dialogue, which is exactly what Bridge does here. I mean you have two characters exchanging dialogue who aren’t even talking to each other. He’s talking to her. She’s talking to us. It’s creativity like this that opens the door for a slew of new options.

The next thing Fleabag does is she talks about things you’re not supposed talk about. Again, this doesn’t come out of nowhere. It’s baked into the character so you have to make that choice early on. But once it’s there, it’s powerful because there are very few things left that are taboo. And the fact that Fleabag consistently finds the taboo subject and talks about it so openly provides something very rare in movie and TV dialogue, which is that you don’t know what the character is going to say next.

You know how in 90% of movie conversations, you can approximately predict what the next line is going to be? Those moments never happen on Fleabag. You’re always unsure of what she’s going to say next and that’s a major key to keeping people watching. As soon as audiences figure out what’s coming next, what’s their incentive to continue?

I don’t want to overlook the technical side of dialogue here so I want you to go back to the first page and reread Fleabag’s opening monologue. Notice that IT’S ONLY ONE SENTENCE. It’s not grammatically correct. It’s not aesthetically perfect. It’s a big messy run-on sentence. However, it fits the character and it fits the situation. She’s someone who rambles on, especially when she’s drunk and horny. If this monologue had been broken into four proper sentences, it wouldn’t have felt right.

Finally, the dialogue is honest and authentic to the character who’s speaking. It isn’t movie-logic dialogue where the writer is attempting to imprint their cool lines or relevant thoughts onto the character. “But you’re drunk, and he made the effort to come all the way here so, you let him.” I don’t know a lot of writers who would be willing to go to this place. It’s borderline uncomfortable to hear. But that rawness, that realness, is what makes it authentic.

One of the best ways to study dialogue is to find a scene that has good dialogue then imagine what the scene would’ve been if written by an average writer. Because those are the scenes I read thousands of times over and have become bored by.

I mean think about how many scenes have been written where a guy or girl comes over for a booty call. Now try and think of any that are as good as this scene. Go ahead. I’ll wait. It doesn’t matter. You won’t find one.

I bet you the scenes you tried to find have the obvious funny initial text exchange. Maybe some clever quip about boning. Cut to the guy showing up. There’s some drunk dialogue. Then they smash. It’s just so… predictable.

When you can take that common of a scenario and twist it into something we’ve never seen before, that’s what’s going to set the stage for a good dialogue exchange. Because you can only do so much with the standard setup.

To summarize everything: First we have a dialogue-friendly character. Fleabag says whatever she’s thinking. She has zero tact. Next, the fourth wall option provides an opportunity for dialogue creativity. This makes the scene read different from what we’re used to. The dialogue is risky in places. It’s authentic to the main character. And, overall, there’s a desire to explore and be playful. You’re not going to find good dialogue the way you find a good plot. You have to be more open and relaxed and allow the words to flow through you. If you try to control them or you try and logically build a great dialogue exchange, it’s not going to work. Conversation is often illogical.

It’s funny. Despite Hollywood universally agreeing that Bridge is an amazing dialogue writer, whenever I post one of these breakdowns, there are always commenters who scream out, ‘THIS IS THE WORST DIALOGUE EVER, CARSON! YOU’RE WRONG.’ I welcome these comments. I only ask that you back up your claim. Give us some analysis on why the dialogue is bad. Dialogue is always one of the more polarizing screenwriting topics so I expect some fiery debates.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: When a young man can’t come up with enough money for his wedding, he’s forced to enlist the help of his estranged crazy grandmother, who will only provide the dough if he helps her kill herself.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List with 12 votes. This is writer Patrick Cadigan’s breakthrough screenplay.

Writer: Patrick Cadigan

Details: 111 pages

Everybody in town thinks that when the pandemic is over, Hollywood’s going to want to buy a bunch of dramatic pandemic material.

I’m sure a couple of those projects will sell.

But if you’re looking for to play the smart money, it’s going to be in comedy. In times of stress, people want to laugh. So expect every studio to stock up on comedy projects. Netflix especially. They have the fastest concept-to-distribution model by far. So they can get a lot of these comedies in front of our eyes quickly.

Speaking of comedies, I’m happy that today’s script doesn’t involve a group of female characters going on a raunchy trip together, since that’s all Hollywood was buying for a good five years there. We might actually get back to seeing a variety of comedy projects. Let’s see if “Grandma” starts us off on the right foot.

30-something Ben works the phones at a dying insurance company. So while his career isn’t exactly on the upswing, he does have Mary, his partner-in-crime fiance who he’ll be marrying in a few months.

Mary is perfect in every way except for one. HER FAMILY. They suck. In fact, her father, George, corners Ben at a family gathering and informs him he can’t pay for their wedding. Which means Ben is going to have to come up with 30 grand.

This forces Ben to call his grandmother, Minnie. Minnie is one feisty old broad who tells it how it is. When Ben’s parents died unexpectedly when he was a child, Minnie raised him. The two never got along and Ben escaped the second he was of age to do so. He hasn’t talked to Minnie since.

Ben explains his predicament to Minnie and she comes up with an idea. She’s been planning to euthanize herself for years but she’s needed a family member to sign off on it. If Ben signs the suicide papers, she’ll give him the money.

Ben is thrilled with the arrangement… until he learns that they have to wait 30 days for the suicide. Which means Minnie will be helping Ben and Mary plan the wedding. When she suspects that Mary’s family is a bunch of cheating lying sleazeballs, there’s a good chance that she’s going to blow this wedding up before Ben and Mary can walk down the aisle.

Let’s start off with the good.

A comedy about a wedding where the love story isn’t about the bride and the groom, but rather the groom and his grandmother, was clever. I loved how, at the end, when the priest is reading the vows, Ben stops because he wants to go get his grandmother. It’s the the exact opposite of these “last minute sprint to the wedding” climaxes.

Also, this movie will get made.

It’s basically Bad Grandma and just like Bad Grandpa was able to get Robert DeNiro so it could make its movie, this will get an older famous female actress that ensures this moves into production as well.

But I don’t have any praise beyond that.

One of the hardest things about comedies is getting the balance between plot and comedy right. I’ve read hundreds of failed comedy scripts where my critique was, “You focused so much on the humor that the plot fell apart.” I’ve read almost as many failed comedies where my critique was, “You were so obsessed with structuring this thing that you squeezed out all the comedy.”

The best comedy scripts balance these two things.

Unfortunately, “Grandma” falls into the latter category. It’s so plot-centric that there aren’t any stand-out scenes. In fact, the only stand-out lol scene in the script is the opening flashback funeral (for Ben’s parents).

It shouldn’t be surprising that that’s the only scene that isn’t structurally attached to the story. It’s a flashback separate from everything. Without the constraints of plot, Cadigan only had to worry about being funny. Which is probably why it was the only scene that made us laugh.

Another problem is that Cadigan can’t decide whether Grandma is a comedic character or a straight up caricature. A caricature is a one-dimensional cartoonish character built solely for laughs. Mr. Chow in The Hangover is a caricature.

A comedic character is someone who’s funny, even goofy, but who we actually care about. Jack Byrnes in Meet the Parents is a comedic character.

Cadigan seems to shift Grandma between these two classifications when it’s convenient. She’s a loud-talking swear-a-minute pistol through many of the early scenes. But in the second half, we’re asked to see her as this fully fleshed-out human being with flaws. In the wise words of LaVar Ball – “Pick a lane.”

Finally, I never cared enough about the wedding.

Those are the stakes, right? If Grandma doesn’t help Ben, they can’t have the wedding. But does that mean he’ll lose Mary? Can’t they just get married in Vegas or at the courthouse instead? I never felt like the wedding falling through was the end of the relationship. So the stakes were never high enough.

Contrast this with Meet the Parents where you felt that if Greg didn’t win Jack over, he was going to lose his fiance. They did a great job establishing how much stock she put into her father’s approval.

But let’s be real. LOLs trump all. If you make this funny, we’ll overlook any issues. I’ve consulted on scripts like this before and what I tell the writer is to go through every single big scene and make it as funny as you can without worrying about the plot. Just come up with the funniest possible scenario you can think of.

Then, after you’ve done that, go back and gently edit those scenes so that they retain their new hilariousness but also fit back into the plot, even if that fit isn’t as perfect as before. Again, if we’re laughing, we’re not thinking about whether the script performed a proper “break into Act 2.”

Not a bad script but it’s going to need a few rewrites to get where it wants to be.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The stakes have to be present in the logline. If the stakes feel weak in the logline, you need to rethink your concept. Guys needing to find their kidnapped friend and get him back to his wedding within 24 hours (The Hangover) – high stakes. Guys trying to tag the one friend in their group who’s never been tagged yet before his wedding (Tag) – low stakes. The stakes for this wedding never felt that high to me.