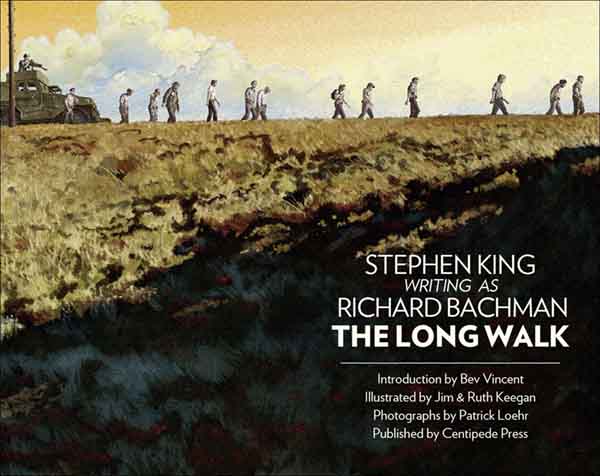

The short story sale only took 45 years to happen

Genre: Dystopian/Sci-Fi Adjacent

Premise: 100 teen boys participate in an annual event that forces them to do a death walk until there is only one left.

About: Okay, I’m cheating a little. This isn’t technically a short story. But it’s a short story in Stephen King Language, as the man is known for writing 700 page novels. Technically, he would call this a novella. King also wrote this under his fake author doppelgänger, which King invented once he became too popular and figured everyone was buying his books regardless of whether they were good or not. He wanted to challenge himself and see if he still had it as an author, which is why he invented Bachman. The Long Walk, which is 45 years old at this point, was purchased by Lionsgate and will have Hunger Games director Francis Lawrence direct. The film was almost made twice before, once by George A. Romero and once by Frank Darabont.

Writer: Richard Bachman (Stephen King)

Details: (1979) A little under 250 pages, hardcover.

I’ve decided that I’m going to do a Short Story Showdown at some point this year. I’m not sure when but it will probably be June or July. So start coming up with that short story concept because we can’t deny what the current trend is, which is short stories, short stories, short stories.

If I could give you one piece of short story advice, come up with a big idea. Think “high concept” even more so than you would a script. Cause a lot of these short stories are a quarter the size of a screenplay. So you don’t really have time to put your characters through some complex arc. It’s more about a sexy idea that’s going to generate interest in potential moviegoers.

The Long Walk is a great example of this. It’s all about the idea. Let’s see if it offers us anything else.

16 year-old Ray Garraty was chosen to be one of the contestants for The Long Walk, a yearly competition where thousands of boys enter their names in a hat for a chance to compete for the grand prize – all the money you need for the rest of your life. Only 100 names are chosen and Ray is one.

No sooner do we meet Ray than the walk begins! The rules are simple. You have to keep up a pace of 4 miles per hour. If you don’t, you get a warning. You get three warnings total. The fourth time, they shoot you. As in, THEY KILL YOU. The last remaining person to be walking is the winner.

Ray immediately teams up with a guy named Peter McVries. Whereas Ray is more of a wholesome chap, Peter’s got an edge to him. It feels like he’s hiding a few secrets inside that noggin of his. But Peter seems to be as supportive of Ray as he is himself. The two lean on each other a lot as the first contestants “buy their ticket” (Long Walk code for “shot dead”).

The story doesn’t deviate much. It leans into the long grueling competition of trying to keep walking when you’re tired, when you get a Charlie horse, when you get a cramp, when you’re bored, when you get blisters on top of your blisters, when your shoes come apart, when your body wants to give in. Many a contestant tries to game the system – run into the crowd to escape, thinking the guards won’t possibly shoot at them. But it never works. The crowd wants to see them die so they push them back to allow the guards a clear shot.

15 miles turns into 20. 20 to 50. 50 to 100. Days go by. 5 of them in all. Somehow, some way, Ray keeps going. At a certain point, it’s just Peter and Ray. (Spoiler) But then Peter can’t go on. He’s too exhausted. Which means Ray is going to win. When Peter is shot, that’s exactly what we think. It’s over. But did Peter lose count? Is there another player he must outlast? Or is that player death himself? Is Peter even in the game anymore?

A few of you are probably asking, “Why’d you pick this to read, Carson?” Here’s why. The Hollywood system is so obsessed with the word “no,” due to the fact that it keeps them from having to make a decision, that when they finally say “Yes” to something, it’s a really big deal. It’s so hard for any executive to say yes because they know, once they do, that project could go horribly bad and, if it does, they’ll be fired. It’s probably the best view into an exec’s mind you’re going to get. Committing to anything is so daunting that there HAS TO BE SOMETHING SPECIAL about that project for them to say yes to it.

But if I’m being honest with you, the real reason I chose to read this as opposed to a script that sold or a script that made the Black List, is that I knew it was going to be entertaining. King has his storytelling faults. But his stories always place “entertaining the reader” first. So I know I’m going to enjoy the experience of reading The Long Walk.

I’ve read too many scripts to know that most writers don’t prioritize entertainment when writing a story. They’re writing for their own egotistical reasons. Or they’re trying to write something that’s taken seriously. Or they think that readers will stay with them for thirty pages of setup to get to the good stuff.

All King thinks about is the reader. That’s why he’s the most well-known living author. If every writer could take in just a quarter of that desire that King has to entertain people, their scripts and stories would be so much better.

And that’s exactly what happened. I was entertained from the jump.

I mean, do you know how quickly we get to the walk here? Within the first ONE PERCENT of the story! That’s how determined King is to entertain. He knows why you bought this book and he’s going to deliver on that promise. This is especially important with short stories. Not only do you need a high concept premise. But you need to get into that premise faster than when you’re writing a script.

What’s interesting here is that the entertainment comes at us in an unorthodox way. I’m not surprised at all that George Romero was once attached to this because the deaths here aren’t fast and furious. They work more like zombie deaths, where they come slowly. The people involved realize minutes, sometimes hours, ahead of time, that their death is coming. This makes the deaths more realistic, intense, and emotional.

When one kid tells Ray that he’s got a cramp and he’s looking to Ray for help, Ray looks back at him like, “I can’t do anything for you.” And the realization this kid has that nobody can help him is devastating.

That’s the majority of the book. King introduces us to kids along the way, tells us just enough about them to get us to care, then kills them off later on.

Another thing I liked about this story was the rules.

As with any sci-fi (or sci-fi adjacent) story, you have to have rules. Where so many writers screw up is they make their rules too complicated. Or they have too many of them. Or both. Note how simple the rules are here. You have to keep up a 4mph pace. You get three warnings. On the fourth, they shoot you. That’s it! For some reason, writers think that they’re not getting enough out of their story if the rules are simple. So they invent all these complicated rules. But the opposite is true. When the reader easily understands the rules, all they have to do is enjoy the story. They don’t have to constantly rack their brain to remember a + z = q.

Another great lesson you can take from this story is how impossible King makes it feel. With every script you write, you need to make the goal as impossible-feeling as you can AS EARLY as you can.

Ray is not dead tired on mile 97 when there are 3 kids left. He’s dead tired on mile 20 with 97 kids left. That’s how to make the reader wonder, “How in the world is he going to last?” And if the reader is asking that question, I guarantee they’ll keep turning the pages. It’s only when there are no questions left to answer, or the answers to the questions are obvious, that the reader stops reading.

The story does have narrative limitations. It starts to get monotonous since there’s only one thing to do. And I thought that King could’ve done more with the Ray and Peter friendship. If he could’ve made us love this friendship, like he did the kids in Stand By Me, their final walk together would’ve been a lot more emotional. And then, the ending needs work. You could tell King didn’t know how to end this. Luckily, there are options here, starting with strengthening that friendship.

Overall, a solid story that should be a good, but not great, movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A sound strategy for screenwriting is to see what the hot new trend is and go back through your finished scripts to see if you have anything similar. You can do this starting from scratch (writing a brand new script) as well. But trends are finicky. They can last a year. They can last five years. So any sort of head start is preferable. There’s no doubt in my mind that this story got purchased due to the success of Squid Game. And, to be fair, it’s been a while since that show came out. Regardless of that, the quicker you can move on a trend, the better. So if you have that old abandoned spec that is similar to the hot new thing, dust it off, give it a quick rewrite, and get it out there!

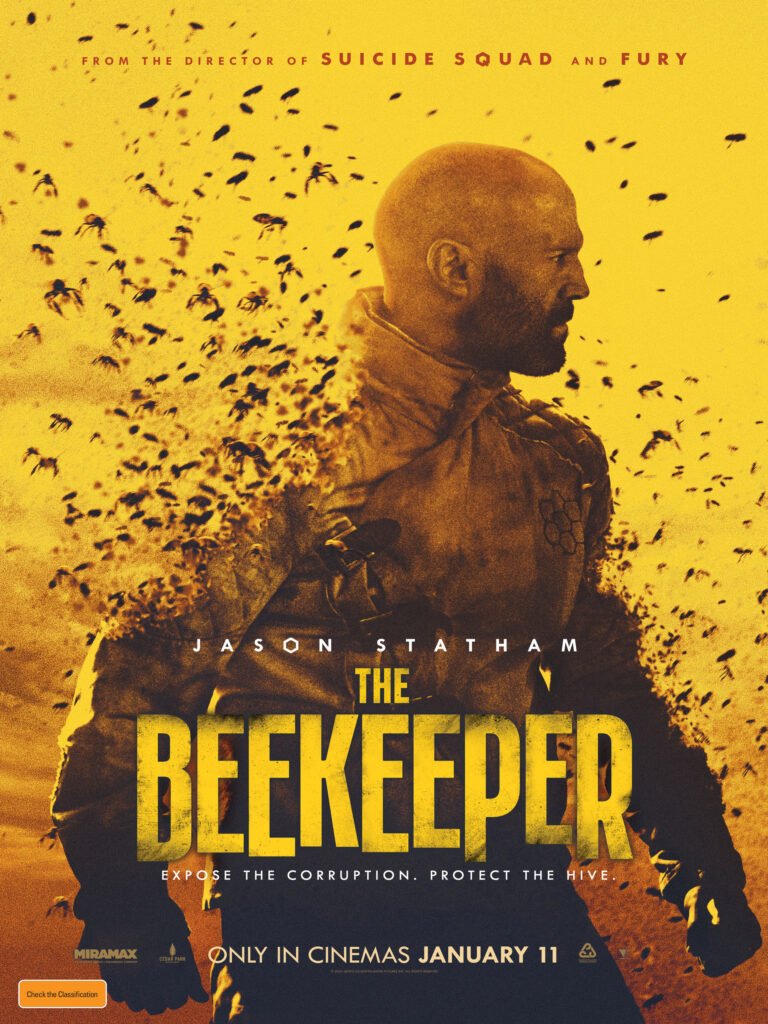

I tell you how The Beekeeper script sold for a million bucks and share with you some screenwriting lessons from Anatomy of a Fall and Self-Reliance

January is always a funky month in the box office schedule. It used to be a dumping ground for studio movies that tested terribly but, these days, if you have a marketable movie, fun things can happen. Which is why Mean Girls pulled in north of 30 million bucks this weekend.

A lot has been made of the fact that Mean Girls hid that it was a musical in order to get more people to show up. This strategy has always baffled me (they did it with Wonka as well). If you know people don’t want to show up to a musical, why did you make a musical?

Cause neither of these films needed to be musicals. They each would’ve worked as regular movies. I’m guessing in the case of Wonka, it was to get Timothee Chalamet on board. These vain actors are all about proving how versatile they are. So if Chalamet is offered ten common roles and one musical, he’s going to take the musical. Cause that’s the one where he gets to prove the most. So maybe they did it to get him and then began their crusade to convince the rest of the world that they weren’t actually making a musical.

Whatever decisions led to keeping Mean Girls’ dirty little secret, I’m not sure it mattered. Mean Girls is a classic film. It’s still referenced today. So it did well for the same reasons that most franchises do well these days – nostalgia.

The movie I was keeping closer tabs on was The Beekeeper. I reviewed the script last year and loved it. Kurt Wimmer is one of my favorite spec script writers. There are few screenwriters who know how to make readers turn the page better than him.

His process is a strange one, too. He writes 12 screenplays a year – a new one every month. And then he just keeps his ear to the ground on what people are looking for. If an opportunity comes up (his agent calls and says Gerard Butler really wants to make a helicopter film), he goes through his giant script database to see if he’s got a helicopter script.

The way this project came together – and I know this cause Kurt told me – is that Kurt had a previous relationship with Jason Statham and Statham had just gone through a major upheaval with his representation. He fired his agents and managers. He then called Kurt and said, “Do you got anything for me?” And Kurt had just finished The Beekeeper. Statham loved the sound of it and he was in.

I think the reason it’s doing solid business and that audiences are really liking it is that there’s nothing else out there like it. It’s kinda weird. It’s kinda silly. Yet it has this hardcore action component. It really is its own thing. Which is something I tell all writers – you have to give us a script that differentiates itself from all the other scripts out there. You can’t expect to write Type 1 concepts and get people excited.

Will Beekeeper become a franchise? If so, it has to pull off what John Wick did. Not a ton of people saw John Wick when it first hit theaters. It took off once it came to digital. That told Lionsgate that there was a big audience for the film, which is why they gambled on a bigger budget sequel. When that did well, each successive film budget got higher.

Cause, right now, The Beekeeper can’t compete on an action level with John Wick 4 or Fast and Furious. It doesn’t have the budget. To get that budget, it needs to perform like gangbusters on streaming. That’s probably the template for anyone wanting to build a franchise from scratch these days. It’s not like The Matrix anymore, where you become a franchise the first movie out. You have to build that audience.

I watched a couple of movies this past week, each of which provided screenplay lessons. The first was Anatomy of a Fall, which is a big awards contender. It’s a French movie that follows this married writer who lives with her husband and blind 12 year old son out in the middle of nowhere.

One day the husband’s dead body ends up in front of the house and it’s unclear whether he accidentally fell from the third floor, purposely jumped to commit suicide, or if his wife, our protagonist, attacked and pushed him off. The majority of the movie takes place in a courtroom where the prosecution tries to prove that she murdered her husband.

First of all, the movie’s fun to watch if only to see how the French court system works. It’s so bizarre and different from American court. It’s a lot more theatrical. You can’t believe that that’s how they really try people for murder.

But, beyond that, the movie is a failure (spoilers follow) due to the fact that they never tell you if she murdered him or not. If you’re going to build your entire premise around the question of did a woman kill or not kill her husband, then NOT GIVING US THAT ANSWER is cowardly.

You’re a coward because you were afraid to make a creative choice. I say this not just because of this movie. But because I see it all the time in screenwriting. A writer builds their entire story around a question, then doesn’t give the reader the answer. In their minds, they are being artistically courageous. Only hacky mainstream Hollywood movies answer questions, they reason. “Real” movies, movies with “artistic merit,” are vague and ambiguous. They allow the audience to come to their own conclusions.

Bulls#$%.

You can tell yourself that. But what you really are is spineless. You see, if you fashion yourself an “artist,” you can’t give your script a Hollywood ending. So you can’t give us the mainstream answer, which is that she didn’t murder her husband.

However, since there are only two options here – she did or didn’t do it – you know that the jaded readers will find the other avenue just as cliche. In other words, if you say that she did it, the “cool kids” in the audience will roll their eyes and say, “Of course she did. We saw that coming from a mile away.”

So your solution is to not give us any answer. “You figure it out,” you say.

Let me make something clear to you. If you are offloading the work that YOU SHOULD BE DOING and making the reader do it instead, you’re not being an artist. You’re just afraid to make a choice.

Is making a choice going to make some people unhappy? Of course. But it’s your job as a writer to write with conviction. Stand behind your choices. Write towards something you want to say. Don’t make the audience do the work for you. That’s lame. Because I know this writer knows if she killed her husband. They were just afraid to share that truth. That’s unacceptable.

Another movie I watched this weekend was a film on Hulu called Self-Reliance. Jake Johnson writes and stars in the movie. I’m a Johnson fan because he’s from Chicago (where I’m from) and there’s not one person I know who better looks and acts like a Chicagoan than Jake Johnson. Sometimes, when he speaks, I feel like I’m listening to myself.

The movie follows a guy with a boring job whose 15-year girlfriend broke up with him so he moves back in with his mother. Then, one day, he’s approached by some people who tell him he’s been chosen for a game. The game is a dark web game where he’ll be remotely recorded and people will try and kill him. If he can survive for 30 days without getting killed, he wins a million dollars.

He decides to join the game because of a small loophole in the rules which states that he can’t be killed as long as he’s with somebody. So he figures, I’ll just keep someone next to me the whole 30 days. As it turns out, being physically within someone’s presence 24 hours a day isn’t as easy as it seems.

A few people e-mailed me after my Concept Post on Thursday and asked, “Is it possible to write a low-budget Type 2 concept?” And the answer is, “Yes.” To quote the late great Montell Jordan: “This is how you do it.” This story is built around a game where you’re trying to avoid assassins for a dark web audience. It doesn’t get any more high concept than that.

Unfortunately, this script is an example of what happens when a newbie writer makes a movie. I know that Johnson has writing credits on a few other films but, from what I understand, those were improvised acting movies where the director gave him a writing credit cause he was making up his dialogue as he went along. Here, he’s actually writing a script.

Where newbies often go astray is that their tone bounces around too much. Here, we have this dark heavy game. But then later, when he teams up with another female player, it turns into a lighthearted romantic comedy. You can’t do that in screenwriting. You gotta pick a lane.

Actually, let me rephrase that. Anything’s possible. As I pointed out earlier, The Beekeeper is equal parts intense and silly. But The Beekeeper was written by a 30 year professional screenwriter who’s literally written 100+ screenplays. You have to go through the trenches to know how to balance tone. If you’re new to this, trying to fit wildly different tones into the same script is the equivalent of riding a roller coaster standing up. Loopdie-loop? More like loopdie-dead.

In this case, had Jake committed to that darker tone, it would’ve taken a 6 out of 10 movie, which is how IMDB currently rates it, to an 8 out of 10. Cause I was into the movie when it was dark and unpredictable. The second it became a rom-com, my interest nose-dived. So it’s not just about matching tone. It’s about sticking to the story you promised the reader you would tell.

Then again, this is that weird movie month where up is down and north is south. So it might be worth checking out if you liked the sound of the premise. I STILL haven’t watched Holdovers. That’s going to be my next one. Oh, and Sisu. A few people have told me that one was good.

Two quick reminders before I go.

CHOOSE THE CONCEPT FOR THE SCRIPT YOU’RE GOING TO WRITE BEFORE THURSDAY. We’re going to start the outlining process.

Also, this is another reminder that January Logline Showdown is January 25th. So get those loglines to me before then!

Learning the difference between Type 0, Type 1, and Type 2 Concepts

One question I constantly go back and forth on is, “Is concept the most important part of screenwriting?” It’s a challenging question to answer because the other aspects – character, plot, dialogue – take so much more time to construct and integrate into a screenplay. So it’s easy to see them as being more important.

But the thing with concept is that it informs everything. It informs your characters. It informs your plot. It informs your dialogue and what kind of scenes you write. So even though it’s just this tiny little sentence, it’s probably the most important aspect of your script. Pick the right concept and the script writes itself. Pick the wrong one and you could spend years trying to improve something that’s already hit its ceiling.

For those who pop in and out irregularly, I’m challenging the Scriptshadow readers to write two scripts this year. I’m going to guide you through both of those experiences every Thursday for the rest of the year. I’ve given you two weeks to come up with a concept which means you’ve got one week left.

As I pointed out in my original “2 Scripts in 2024” post, I’d encourage you to choose a strong concept – something that would give you a clear poster and a clear trailer. Before you purists scream out that you will not be pigeonholed by the Hollywood establishment, take note of how you choose which movies YOU watch. You usually see a poster, watch a trailer, or hear about the idea online and it catches your interest.

If you’re not thinking about how people receive your idea, if you’re not asking whether they’ll be excited when they hear your idea, you’re probably picking a weak idea. Sure, you can utilize the strategy of, what I’m interested in, others will be interested in. But I’d only go that route if you have a good feel for popular culture and what people like. If your instinct is to write scripts like Past Lives or Drive My Car, you do not want to be using that strategy. Trust me.

Since talking about concept in a vacuum isn’t very helpful, I want to get more specific. After being pitched thousands of script ideas, I’ve found that you can break concepts into three types.

TYPE 0 – These are concepts that aren’t marketable or clever. This would be something like Minari or Mank or Roma. I’m not saying you should never write a script like this. But it’s important to understand that, by doing so, you are making a 1 in ten thousand shot a 1 in one billion shot. So write these at your own risk.

TYPE 1 – These are concepts that are marketable. They’re tried-and-true formulas that fit into specific genres and sub-genres that the industry has been making money off of for decades. If you write a body-swap script, that’s a Type 1. If you write a John Wick clone, that’s a Type 1. The good thing about Type 1 concepts is that they have a real shot at being turned into movies if they’re good. The bad thing is that they don’t give you anything else. It’s a straight-down-the-middle exploration of that genre and, therefore, you won’t get a ton of read requests. You’ll get way more than Type 0s. But unless an exec is looking for a project like that at the time, they’re going to be reluctant to request a read.

TYPE 2 – Type 2 concepts give you the marketability you get from Type 1 AS WELL AS SOMETHING EXTRA. Usually, this means an exciting x-factor or a component that makes the idea clever. For that reason, these are the concepts that are going to get you the most reads. The classic example of a Type 2 Concept is The Hangover. If that movie had only been about three guys going to Vegas for a crazy bachelor weekend, it would’ve been a Type 1 concept. By having them all forget the previous night and have to find the lost groom the next day using clues from the previous evening – that’s what made the premise clever and, therefore, graduate to a Type 2.

So there’s no confusion, these types don’t represent every idea out there. They’re only the types I see the most often. I’m not sure what category “Dream Scenario” would be in, for example. It’s not quite marketable but it does have a unique premise. There are also concepts like Knock at the Cabin. It has that marketable component as well as something a little bit different about it. But I’m not sure it has enough of a unique hook to graduate to Type 2. Maybe I’d place it at a 1.5. The point is, I want you to use these as guidelines, and guidelines only, for choosing your concepts.

What follows is a list of Type 0, Type 1, and Type 2 concepts for clarity.

TYPE 0 CONCEPTS (avoid these unless you’re extremely passionate about the idea)

Nomadland – People driving around without destinations. Type 0.

Fences – A drama about backyards. Type 0.

Dallas Buyers Club – Melodramatic script about AIDS. Type 0.

The Holdovers – Staying at a college during winter break and exploring character development during that isn’t a sexy enough idea to write on spec. Type 0.

A Good Person – When you have an idea that feels like something you can see in the everyday world – such as a movie chronicling a regular family’s problems – it’s almost certainly a Type 0.

The Iron Claw – A tragic story. The rareness of the wrestling subject matter gives it a little more gusto than your average Type 0. But it’s still a Type 0.

Marriage Story – Watching the last stages of a marriage in drama format is Type 0.

Licorice Pizza – This is an interesting one because it has a lot of unique elements. But it doesn’t have any clear concept that stands out, which is what makes it a Type 0.

Lady Bird – Straight-forward coming-of-age films are almost all Type 0s. They rarely get made unless the writer is directing the film. That’s a good sign of a Type 0, by the way. If no one OTHER THAN THE WRITER is interested in making the movie, it’s a Type 0.

Aftersun – From everything I’ve heard, this is a good movie. But it’s virtually unmarketable due to its concept-less premise. A good way to spot Type 0s are movies that get all these awards yet you STILL have no interest in seeing them. One quick extra note. Just because you want to see Aftersun does not make it marketable. As someone who follows the movie industry, you are a unique consumer. You are not the average consumer. When coming up with ideas, you want to have the average consumer in mind.

TYPE 1 CONCEPTS (a good middle-ground concept to build a script around)

The Equalizer – Straight-forward guy-with-a-gun story. A little bit of uniqueness (he helps the less fortunate fight the bad guys). But not enough for Type 2 status.

Bullet Train – An assassin on a bullet train. This may be a 1.5 but it’s definitely not a Type 2. There’s nothing unique enough or clever enough about the premise to warrant that label.

Moonfall – These giant disaster movies used to be Type 2s but they became so ubiquitous that they were sent down to Type 1.

Anyone But You – A straightforward romantic comedy premise.

The Boogeyman – Any horror movie with an evil monster is Type 1.

Extraction – This is a good example of what a solid Type 1 concept looks like. We’re setting the story in a place we don’t usually get to see in movies like this (India), which gives it just enough of a bump to get directors and actors interested.

Oppenheimer – Any biopic or true story that chronicles famous people throughout history is automatically a Type 1.

The Other Guys – Any mismatched cops teaming up is going to be a Type 1.

Knives Out – An established sub-genre: Get a whole bunch of people in the same area and have something go wrong. These setups are not far off from Type 2 if you can find a unique way in or an unexpected execution.

47 Meters Down – All shark movies are going to be at least a Type 1. The contained nature of the characters’ predicament gets this a little closer to Type 2. But there isn’t that one thing about it that truly stands out – that strange attractor – to bring it to that level.

TYPE 2 CONCEPTS (these are the concepts you want to write, if possible)

Plane – A plane making an emergency landing in a war-torn country is Type 1.5 territory. Needing to depend on one of the passengers, an accused murderer, makes it Type 2. Whenever there’s irony in a premise (The hero is a murderer), you’re usually in Type 2 territory.

Room – This one’s a little debatable. It’s a contained thriller, which is a high-grade Type 1 concept. I say “high grade” because people trapped inside a place, trying to get out, is always going to be an exciting situation to watch. The uniqueness of sharing a kid with her captor and using him to escape eases this up into Type 2 territory.

Cocaine Bear – A group of people running from something scary in the forest is an idea as old as time and is, therefore, a Type 1. But no one’s ever made the scary thing a bear high on cocaine. That’s what makes it Type 2.

Bird Box – End of the world scenarios are automatically Type 1. The unique element here is that if you look at the evil thing, you kill yourself, forcing everyone to walk around blind.

Gravity – Being stuck up in space after your ship’s been destroyed is almost a Type 2 all on its own. But the real-time component solidified this script’s Type 2 status.

Her – A romance between a man and a woman is Type 1 territory. But once you make one of the parties a computer, it’s a Type 2.

Get Out – An easy call with this one. It’s not just about a black man being introduced to his white girlfriend’s family. But it’s about the freaky weird stuff going on within that family.

The Lost City – Romance in the jungle is a lesser-known but established sub-genre that makes money for Hollywood. What elevates this to Type 2 is having the clueless model who is on the front of the main character’s books being tasked with playing the actual part of that model in this real-life adventure with the author. Irony = Type 2.

Leave The World Behind – This one’s debatable. There are a lot of “End of the World” concepts out there. But this one evolves via a series of mysteries that, I believe, elevate it to Type 2.

65 – If you’re intersecting human beings with dinosaurs, it is almost always going to be a Type 2 idea.

The Last Voyage of the Demeter – It’s not just Dracula killing people in a city. That’s Type 1. It’s Dracula being shipped on a boat, breaking free, and killing everyone on board. That’s what makes it Type 2.

Just so there’s no confusion, none of these examples represent the quality of the movies themselves. I’ve heard some great things about some of my Type 0 examples and watched several of my Type 2 examples fail at the box office. All we’re trying to do here is understand which types of scripts get requested the most, as that’s the biggest determining factor in your script getting optioned or sold. You can’t sell a script that only five people read. It takes A LOT OF NO’S before you find your yes. Which is why I encourage you to write Type 2 concepts if possible. If not, then at least Type 1.

One week left, people. The real work starts next Thursday! :)

Genre: Comedy

Premise: In the early 2000s, two totally opposite best friends, Mike (an uptight lawyer) and BJ (a stoner slacker), awake one morning to find that they have swapped bodies, are stuck in a time loop, and are afflicted with many other high-concept comedy premises of that era. Drawing upon their knowledge of those type of movies, Mike & BJ must learn their lesson(s) and get their lives back to normal.

About: This script finished number 5 on last year’s Black List!

Writers: Alex Kavutskiy & Ryan Perez

Details: 110 pages

Jermaine Fowler for BJ?

Jermaine Fowler for BJ?

First of all, it took everything in my power not to call an emergency press conference about the new Star Wars Mandalorian/Grogu movie announcement. Cause I got a loooottttt of opinions on that. But cooler heads prevailed when I realized the film didn’t have anything to do with screenwriting. I will be addressing it at some point, though – probably in the newsletter.

Speaking of Grogu, I’d be curious what that little green matcha shake thought about today’s script because today’s script starts with a preparatory page. The writers prepare you for how to read their script! They talk about what inspired the script and which actors should play the parts and which tone should be in the back of your mind while reading. I’m not ready to send these two into the Sarlaac Pit for this choice, but let’s just say that, if you do your job as a writer, you shouldn’t have to tell the reader how to read your script.

BJ and Mike are roommates. Mike, white, is a trial lawyer who is currently defending a man accused of killing seven men. He’s also preparing to dump his longtime girlfriend, Bethany. BJ, black, currently spends a lot of time watching old VHS tapes while daydreaming of winning over his dream girl, who happens to be Mike’s sister, Julia.

After a drunken night out doing bar trivia, BJ and Mike wake up in each other’s bodies! Not only that, but they soon learn today is the same day as yesterday, and deduce that they’re in a loop. Luckily, the two have watched a lot of movies and understand that the fastest way out of these kerfuffles is to learn a lesson about themselves.

In the meantime, they decide to take advantage of the loop. BJ (in Mike’s body) goes and tries to win the murder case that Mike lost yesterday. While Mike, in BJ’s body, runs to the airport to tell Mike’s sister that he loves her, a task icki-fied by the fact that Mike is trying to win over his own sister.

They’re able to solve these problems but nothing changes. They then learn that BJ’s jerky 10 year old brother, Cody, who had a birthday today, used his blow-out-the-candles wish to become a star player for the Boston Red Sox. The only way to solve this problem, they deduce, is to buy a universal remote at Bed, Bath, and Beyond (a la “Click”) that allows them to stop time. Unfortunately, doing this unleashes even more magical movie premises on them, pushing them deeper and deeper into their movie universe nightmare.

Eventually, they realize that BJ, who stole all the movie tapes from a small rental shop, was cursed with living those movies’ premises when the shop went out of business. The two will have to dig even deeper into what’s wrong with themselves in order to find the big overall lesson each must learn to make all this go away. But are they up to the task??

Adam Devine for Mike?

Adam Devine for Mike?

High Concept is a fun script that never quite becomes as funny as the concept promises. Like a lot of professional comedy scripts, it makes you smile a lot. But it doesn’t make you laugh enough.

The script has a unique problem specific to body swap scripts. I can speak to this issue because I’ve read more body-swap scripts than anyone in Hollywood. Once the characters switch bodies, the writers have to make a choice on how to name the characters. Do you say, “BJ (AS MIKE)” before every line? Or “MIKE (as BJ)?” Do you prompt the reader, after the body switch, with an explanation as to how the new naming situation is going to work? Or do you do what these writers did and simply keep the same names but expect us to understand that the new characters are in those bodies, and therefore even though BJ is speaking, we understand that it’s Mike?

Unfortunately, I have never found a perfect system for this. It’s always confusing to read. But what these writers do is probably the most confusing option. For me to mentally understand that every time Mike is talking, it’s BJ, is not easy to do. And I did find it funny that the writers spent an inordinate amount of time explaining to you how to read their script and not a single line on how to understand which character was talking after the body switch.

Man, Carson. You’re brutal. Did you laugh at all? Yes, I did laugh, thank you very much. The writers do a great job establishing how Bethany is an awful person to BJ. So when BJ is in Mike’s body and gets to dump Bethany, he doesn’t hold back. Mike even tells him beforehand, “Be nice. Let her down easy.” And we watch the whole thing from outside the restaurant as BJ (in Mike’s body) is screaming at her, letting out years of frustration of having to deal with this girl, ending with him throwing a drink in her face, apropos of nothing. That part I laughed at.

I also thought everything with Mike having to romance his own sister was funny. Because of the loop situation, he tries everything under the sun to win over Julia for BJ. When he finally does it and Julia falls for him, the bewitched onlookers cheer them on, pushing them to “KISS KISS KISS!” So Mike has to kiss his own sister. And we see how incredibly grossed out he is as it’s happening. I thought that was funny.

And there were a few other legitimate laugh out loud moments. But that’s why comedy is soooooo hard. It’s hard getting a SINGLE legitimate laugh from a reader. Yet a good comedy script needs to make the reader laugh out loud 25-30 times. That’s why you really have to be a comedy expert to pull a comedy spec off. Also, there came a point in this script where the number of movie rules we had to keep track of began to impede on the jokes. If I have to remember a body-swap time-loop kid-makes-a-wish universal-remote-control honey-I-shrunk-the-kids combo to get a joke, you’re probably asking too much from the reader.

I have a lot of respect for these writers, though. They swung for the fences. This was not an easy premise to tackle. And they did make it all make sense in the end. Which not many writers could’ve done. But I was just telling this to a writer earlier today in a Zoom consultation about his comedy script. All the reader cares about in the end with comedies is “did I laugh enough?” The plot is secondary. I didn’t laugh enough here to recommend it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the mistakes I see comedy writers make is they don’t let their scenes breathe. Every single scene in this script is 1 and a half pages or less. Usually a lot less. When no scenes are able to breathe, no scenes have a beginning, a middle, or an end. So what the reader experiences is this rapid scene-fragment-after-scene-fragment machine-gun type story. You have to put that 3-4 page scene in there every once and a while. And you need a couple of 7-page set-pieces. The writing style here was so fragmented that I never felt like I was able to connect with these people.

One of the biggest short story sales of 2023!

Genre: Thriller

Premise: An American negotiator in London is called in to help deal with a unique situation – a construction worker is stuck on top of an old World War 2 bomb, which could detonate in response to the slightest movement.

About: This is the big flashy short story sale that happened recently, which landed Ridley Freaking Scott as director. Ridley Scott, who’s making Gladiator movies, for goodness sake, is not easy to lock down into a director role, especially at 85, when he only has so many bites at the apple left. So to say my anticipation levels for this one are soaring would be an understatement.

Writer: Kevin McMullin

Details: 5250 words. I know this because the writer tells us that on the first page. Will this now become the standard for short stories? (An average script is 22,000 words)

I have one question for you. Are you on the short story train yet?

Cause the train is moving people. It’s zipping and zapping its way around Hollywood – down through Culver City into the Sony Lot, up Highland before stopping at Paramount, over to Pico to give all the Fox Studio execs high fives, before muscling up the 101 into the Valley to visit all the valley girl studios.

Someone asked me the other day, “Is the spec script dead?” I said, “No! It’s just morphed into the spec short story.” And here’s the trick that writers are starting to get wise to – when you send your short story out there, you sell it with the stipulation that you get to write the first draft. Which means – if you’re paying attention – you ARE selling a spec script. You’re actually selling it before it’s written. Which means you’re a screenwriting time machine. That’s so much cooler than being a boring spec script writer.

Fear not, script purists. The short story craze does not mean you should drop all your screenwriting aspirations. The industry still needs screenwriters. They can’t live without them. So you should still be writing scripts that wow people so that you can get hired to write all those other projects Hollywood wants to make.

Today, however, we’re doing another short story dance. So throw on your dance shoes and join me. I’ll lead.

American Francis Ipolito, a negotiator, is getting married in the UK over the weekend. He’s staying alone in his hotel room the night before the wedding. That is until his best friend and best man, FBI officer Dwight, calls him and tells him to check the news. Francis does and sees that Piccadilly Circus (London’s Times Square) is cleared out.

In a dug-up construction area, a construction worker is standing on top of an old World War 2 bomb. These bombs are known to be delicate. Even the slightest move could detonate them. So the man is frozen. Less than ten minutes later, a UK government official shows up at Francis’s hotel and says to come with him. Francis says, “Only if my buddy Dwight can join me.”

Once at the bomb site, Ministry of Defense Aoife Greggor tells Dwight to beat it and informs Francis that the whole World War 2 bomb thing was a lie. They put that out there for the press. The real deal is that the construction worker BUILT THIS GIANT BOMB he’s standing on top of and has demanded to talk with Francis.

Francis heads over to the Piccadilly construction site, with no idea of who this dude is, only to learn that he’s his fiancé’s ex-husband! Francis is called back to base, where he’s then informed that his buddy, Dwight, was given clearance to join a UK reconnaissance team charged with clearing the surrounding buildings.

Their first building they’re clearing is actually the one Dwight happened to be staying in via Air BnB. Francis freaks out, tells them to get the team out of there as soon as possible. But it’s too late. We hear a big BOOOOM. Dwight is now dead from a second bomb that the bomber planted earlier. Francis turns to Aoife: ‘How many bombs are there?’ The End.

I kid you not. That’s the end of the story.

I sensed something was off with this one right away.

The writing was clunkier than a ride in a square-wheeled wagon. I was constantly having to go back and re-read things to properly understand them. Even then, I didn’t always get what had been written.

This caused me to lose confidence in the writer as the story went on. For that reason, I knew it wasn’t going to deliver. But what I didn’t know was how spectacularly it would fail to deliver. I mean this isn’t just a bad short story. This is bad everything.

I don’t want to be mean because it isn’t the writer’s fault that his story sold and nabbed one of the best directors in the business. But with that success, readers are going to go into this with high expectations. And man, let me tell, this is not the kind of story you want people reading with high expectations. You want them going in with subterranean expectations. Even then, though, they’ll be disappointed.

Let me give you an example of how bad the writing is. It’s late in the story. There are a few pages left. Francis has just come back from talking to the bomber dude and asks Aoife where Dwight is.

Aofie, who mind you hated Dwight and was trying to get rid of him since the second he showed up, informs Francis that Dwight has joined the British reconnaissance team. Even if we stopped there, that’s terrible writing. There’s no way any British service is going to have some random off-duty American FBI guy join their team on the spot. Also, you’ve set up that the Ministry of Defense hated this guy. So why would she allow him to join one of her teams?? In less than five minutes no less!!????

But it gets worse!

Aofie tells Francis that the team is investigating a building nearby, a building that just so happens to ALSO be the AirBnb apartment Dwight is staying at. In that moment, Francis realizes that this was all part of the bomber’s plan. So he tells Aofie to get the men out of that building as quickly as possible. But before they can act, the building blows up from a DIFFERENT BOMB the bomber planted earlier, and Dwight is dead.

Think about that for a second. The number of hoops we need to jump through for this to make sense is astounding.

In order for the bomber’s plan to work, he would’ve had to secretly set up a bomb weeks ago below Dwight’s AirBnB building AND THEN, since Dwight wasn’t actually at the building, the writer needed to construct a scenario by which the British bomb team recruited Dwight on the spot, and then, of the hundreds of surrounding buildings they could’ve gone to, the writer made the team coincidentally go to Dwight’s AirBnB building, so that the bomber could kill him.

All of this was done via a payoff THAT WAS NEVER SET UP. Because we didn’t even know about any other bombs until the second one blew up. So none of it feels earned or realistic. It’s the kind of sloppy writing that even low-level Hollywood execs don’t let fly.

Everywhere you look in this story, it’s bad. There are no positive attributes at all other than it’s sort-of high concept. It was one of those situations where I actually thought I got duped – that someone sent me the wrong “Bomb” story. That’s how ugly it got.

This begs the question. If this story is so bad, why was it purchased? One of the frustrating things I’ve learned about Hollywood is that every working individual has their specific movies that THEY WANT TO MAKE. Only that person and their close friends know what those movies are. We, outside the business, don’t know what they are. So we can’t write the script that Denzel Washington is desperate to make or pitch the movie Jacob Elordi has wanted to be in since he was five.

I suspect that Ridley Scott really wanted to make a negotiator movie or a bomb movie and this came across his desk. Boom. That’s it. He was in because this is the exact type of movie he wants to make right now. And make no mistake, after he lets McMullin write his contract-guaranteed first draft, he will bring in a much more established screenwriter to write a version of this that actually makes sense. Cause if he goes with this version, it will be one of his worst movies ever.

Of all the short story sales I’ve seen so far, this is by far the worst.

[x] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned 2: Is getting married a short story sale hack? This is the second big sale in a row (the last was Run For Your Life) where an impending wedding was the centerpiece. Weddings give you ticking time bombs and heightened emotions, both of which create more drama. Not saying you SHOULD use a wedding. But there’s clearly something to it.