Search Results for: 10 tips from

Because my original Aliens post is still somewhere in Blogger’s belly, I’m reposting it until they belch it back up. Unfortunately, that means that the previous comments won’t show up here, and any new comments you post won’t show up when I bring back the original post. But for reading purposes, here you go. :) (thank Clint Clark for getting this for me)

Aliens is, quite simply, awesome. It’s one of those movies that works if you’re 15 or you’re 35. It’s got action. It’s got mystery. It’s got emotion. And it’s in the running for best sequel ever. When I give notes, there’s no movie I reference more than this one. I’ve been known to bring up Aliens while consulting on a romantic comedy. That’s how rich it is in screenwriting advice. Now I could sit here and whine that “Studios just don’t make summer movies like this anymore.” But the truth is, they’ve never made these kinds of summer movies consistently – movies with depth, movies with thought, movies where the story takes precedence over the effects. But when they do, it’s probably the best moviegoing experience you can have. So, keeping that in mind, here are ten screenwriting lessons you can learn from one of the best summer movies of all time.

KILL YOUR BABIES

Listening in on the director’s commentary of Aliens, you find out that Aliens was originally 30 minutes longer, as it included an extra early sequence of the LV-426 colonists being attacked by the aliens. Under the gun to deliver a 2 hour and 10 minute film, Cameron reluctantly cut the sequence at the last second, and wow did it make a difference. Without it, there was more build-up to the aliens, more suspense, more anticipation. We were practically bursting with every peek around a corner, every blip of the radar. Now Cameron only figured this out AFTER he shot the unnecessary footage, but let this be a lesson to all of us screenwriters. Sometimes you gotta get rid of the things you love in order to make the story better. Always ask yourself, “Is this scene/sequence really necessary to tell the story?” You might be surprised by the answer.

NOT EVERY FILM NEEDS A LOVE STORY

There’s a temptation to insert a love story into every movie you write, especially big popcorn movies, since the studios are trying to draw from every “quadrant” possible and therefore need a female love interest to bring in the female demographic. But there are certain stories where no matter what you do, it won’t fit. And if you’ve written one of those stories, don’t try to force it, because we’ll be able to tell. I thought Cameron handled this issue perfectly in Aliens. He knew a love story in this setting wasn’t going to fly, so instead he created “love story light,” between Ripley and Hicks, where we see them flirting, where we can tell that in another situation, they might have worked. But it never goes any further than that because tonally, and story-wise, he knew we wouldn’t have accepted it.

ALWAYS MAKE THINGS WORSE FOR YOUR CHARACTERS

As I’ve stated here many times before, one of the most potent tools a screenwriter possesses is the ability to make things worse for their characters. In action movies, that usually means escalating danger whenever possible. Aliens has one of the most memorable examples of this, when our characters are moving towards the central hub of the station, looking for the colonists, and Ripley realizes that, because they’re sitting on a nuclear reactor, they can’t fire their guns. The Captain informs his Lieutenant that he needs to collect all of the soldiers’ ammo (followed by one of the greatest movie lines ever “What are we supposed to use? Harsh language?”), and now, with our marines moving towards the nest of one of the most dangerous species in the universe, they must take them on WITHOUT FIREPOWER. Always make things worse for your characters!

USE YOUR MID-POINT TO CHANGE THE GAME

Something needs to happen at your midpoint that shifts the dynamic of the story, preferably making things worse for your characters. If you don’t do this, you run the risk of your second half feeling a lot like your first half, and that’s going to lead to boredom for the reader. In Aliens, their objective, once they realize what they’re up against, is to get up to the main ship and nuke the base. The mid-point, then, is when their pick-up ship crashes, leaving them stranded on the planet. Note how this forces them to reevaluate their plan, creating a second half that’s structurally different from the first one (the first half is about going in and kicking ass, the second half is about getting out and staying alive).

GET YOUR HERO OUT THERE DOING SHIT – KEEP THEM ACTIVE

Cameron had a tough task ahead of him when he wrote this script. Ripley, his hero, is on the bottom of the ranking totem pole. How, then, do you believably prop her up to become the de facto Captain of the mission? The answer lies inside one of the most important rules in screenwriting: You need to look for any opportunity to keep your hero active. Remember, THIS IS YOUR HERO. They need to be driving the story whenever possible. Cameron does this in subtle ways at first. While watching the marines secure the base, Ripley grabs a headset and makes them check out an acid hole. She then voices her frustration when she doesn’t believe the base to be secured. Then, of course, comes the key moment, when the Captain has a meltdown and she takes control of the tank-car and saves the soldiers herself. The important thing to remember is: Always look for ways to keep your hero active. If they’re in the backseat for too long, we’ll forget about them.

MOVE YOUR STORY ALONG

Beginning writers make this mistake constantly. They add numerous scenes between key plot points that don’t move the story forward. Bad move. You have to move from plot point to plot point quickly. Take a look at the first act here. We get the early boardroom scene where Ripley is informed that colonists have moved onto LV-426. In the very next scene, Burke and the Captain come to Ripley’s quarters to inform her that they’ve lost contact with LV-426. You don’t need 3 scenes of fluff between those two scenes. Just keep the story moving. Get your character(s) to where they need to be (in this case – to LV-426).

THE MORE UNLIKELY THE ACTION, THE MORE CONVINCING THE MOTIVATION MUST BE

You always have to have a reason – a motivation – for your character’s actions. If a character is super happy and loves life, it’s not going to make sense to an audience if they step in front of a bus and kill themselves. You need to motivate their actions. In addition to this, the more unlikely the action, the more convincing the motivation needs to be. So here, Burke wants Ripley to come with them to LV-426 as an advisor. Answer me this. Why the hell would Ripley put herself in jeopardy AGAIN after everything that just happened to her – what with the death of her entire crew, her almost biting it, and barely escaping a concentrated acid filled monster? The motivation here has to be pretty strong. Well, because the military holds Ripley responsible for their destroyed ship, she’s basically been relegated to peasant status for the rest of her life. Burke promises to get her job back as officer if she comes and helps them. That’s a motivation we can buy.

STRONG FATAL FLAW – RARE FOR A SUMMER MOVIE

What I loved about Aliens was that Cameron gave Ripley a fatal flaw. Usually, you don’t see this in a big summer action movie. Producers see it as too much effort for not enough payoff. But giving the main character of your action film an arc – and I’m not talking a cheap arc like alcoholism – is exactly what’s made movies like Aliens stand the test of time while all those other summer movies have faded away. So what is Ripley’s flaw? Trust. Or lack of it. Ripley doesn’t trust Burke. She doesn’t trust this mission. She doesn’t trust the marines. And she especially doesn’t trust Bishop, which is where the key sequences in this character arc play out. In the end, Ripley overcomes her flaw by trusting Bishop to come back and get them. This is why the moment when she and Newt make it to the top of the base is so powerful. For a moment, she was right. Bishop left them there. She never should’ve trusted him. Of course the ship appears at the last second and her arc is complete. She was, indeed, right to leave her trust in someone.

SEQUENCE DOMINATED MOVIE

One way to keep your movie moving is to break it down into sequences. Each sequence should act as a mini-movie. That means there should be a goal for each specific sequence. In the end, the characters either achieve their goal or fail at it, and we then move on to the next sequence. Let’s look at how Aliens does this. Once they’re on LV-426, the goal is to go in and figure out what the fuck is going on (new sequence). Once they find the colony empty, their goal shifts to finding out where the colonists are (new sequence). After that ends with them getting attacked by aliens, their goal becomes get off this rock and nuke the colony (new sequence). Once that fails, their goal becomes secure all passageways so the aliens can’t get to them (new sequence). Once that’s taken care of, the goal is to find a way back up to the ship (new sequence). Because there’s always a goal in place, the story is always moving. Our characters are always DOING SOMETHING (staying ACTIVE). The sequence approach is by no means a requirement, but I’ve found it to be pretty invaluable for action movies.

ACTIONS SPEAK LOUDER THAN WORDS (SHOW DON’T TELL!)

Aliens has one of the best climax fights in the history of cinema (“Get away from her you BITCH.”) And the reason it works so well? Because it was set up earlier, when Ripley shows the marines she’s capable of operating a loader (“Where do you want it?” she asks). Ahh, but I have a little surprise for you. Go pop Aliens in and fast-forward it to the early scene where Burke first comes to recruit Ripley. THIS is actually the first moment where the final fight is set up. “I heard you’re working the cargo docks,” Burke offers, smugly. “Running forklifts and loaders and that sort of thing?” It’s a quick line and I bring it up for an important reason. I bet none of you caught that line. Even if you’ve watched the film five or six times. That line probably slipped right by you. And the significance of it slipping by you is the point of this tip. You should always SHOW instead of TELL. When we SEE Ripley on that loader, it resonates. When we hear it in a line, it “slips right by us.” Had we never physically seen Riply on that loader, and Cameron had depended instead on Burke’s quick line of dialogue? There’s no way that final battle plays as well as it does. Always show. Never tell.

AND THERE YOU HAVE IT

I actually had 15 more tips, but contrary to popular belief, I do have a life, so those will have to wait for another day. I do have a question for all Aliens nerds out there though. How do they pull off the Loader special effects? I know in some cases it’s stop motion. And in other cases, Cameron says there’s a really strong person behind the loader, moving it. But there are certain shots when you can see the loader from the side that aren’t stop motion and nobody’s behind it. So how the hell does it still look so real? I mean, these are 1986 special effects we’re talking about here! Tune in next week where I give you 10 tips on what NOT to do via the disaster that was Alien 3.

Whoa, I’m not usually nervous while writing up Scriptshadow posts but this one’s got me a little jittery. Outside of the prequels, I don’t think there’s been a more documented breakdown of a film’s failure to deliver on an audience’s expectations than that of Indiana Jones And The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull. The thing is, I didn’t participate in that documentation. There was something never quite right to me about a 65 year old Indiana Jones. This was a character built on his vitality, on his youth and strength, so to turn an Indiana Jones film into Space Cowboys 2: Let’s Laugh At The Old Guy, felt like a disaster in waiting.

This allowed me to approach Skull with super-low expectations, and ironically, enjoy the film for what it was – a sloppily constructed summer tentpole film. The movie was clunky and awkward and weird – like a lot of those films tend to be – and seemed to spend most of its running time trying to figure out what it wanted to be rather than just…be.

And I think that’s the ultimate failure of Indiana Jones 4. Clearly, Lucas and Spielberg wanted to make two different movies, and a handful of unfortunate writers were assembled to balance those opposing visions and turn them into a cohesive story.

Now it’s important to know that my goal here is not to rip this movie apart. Millions of internet nerds took care of that long ago. I want to identify the poor screenwriting choices Skull made so we can learn from them and avoid those mistakes in our own writing. So, I give you the opposite of my previous Raiders article: Ten screenwriting no-nos you can learn from Indiana Jones and The Kingdom of The Crystal Skull.

THE PROTAGONIST ISN’T ACTIVE

Remember Raiders of The Lost Ark? Remember my very first observation about that movie? Indiana Jones was ACTIVE! In the very first scene, the man is risking his life to secure a golden idol from a trap-filled cave with death at every corner. When he hears about the Ark’s possible resting place, he’s on the first plane to Nepal, obsessed with locating the mythical relic. In this film? You wanna know what happens in the first scene? Indy’s been captured. Indy is REACTING to everyone else. Indy is doing WHAT OTHERS TELL HIM TO DO. It sets the tone for who Indy will be for the next 2 hours (or is it 3 hours?). He will be a REACTIVE character. He will be following Mutt around on this quest for the crystal skull. And because someone else is driving the story besides our main character, everything seems…less important. Think long and hard if you want to have a reactive hero in your action script. Chances are, it ain’t going to work.

MOVIE TAKES FOREVER TO GET GOING

Remember how quickly Raiders moved? Remember how there wasn’t an ounce of fat on it? A big reason for that was that the story knew what it wanted to be so it was able to get there right away. 15 pages in (FIFTEEN PAGES!) we’re given our goal: Get the Ark Of The Covenant. Contrast that with the bumbling, stumbling, mumbling Skull. Do you know when the plot is revealed to us in this film? Page 30! That’s when Mutt tells Indy about the coded Mayan message. Do you know when we actually START our adventure? Page 38! That’s over 20 pages further along than when Raiders got going. And people wonder why Skull feels like it drags.

PLOT IS UNCLEAR

Clarity in your main character’s central objective is crucial to the audience’s enjoyment of the movie. It’s the key to everything else working in the script. If, for example, in Raiders, we didn’t know that Indiana was looking for the Ark, we wouldn’t have cared nearly as much as we did. Yet that’s exactly how Skull tells its story. We’re never exactly sure what we’re looking for. I mean, the title mentions a crystal skull, but we only find out about the skull once Indy and Mutt locate it. Then what’s the movie about? We’re never sure! Indy’s double-agent buddy mumbles something about a city of gold. Russian Psychic Chick talks about plugging the skull in somewhere. But all this jibber-jabber is incredibly vague and we’re constantly wondering what the endgame is. The point is, the audience is never clear what the characters are going after in Skull and the second we’re unclear about your characters’ objectives, your movie is dead.

DON’T BE TOO ‘WRITERLY’

Someone gave me a note on a script once that I’d never heard before, yet I understood exactly what he meant as soon as I read it. He said my scene was too “writerly”. It’s tricky to define this word, but essentially it’s when you’re too clever for you own good, when a scene seems original and interesting as you write it, but feels false when it’s read. The magnet bullet scene in the beginning of Indy 4 is a “writerly” scene. I’m sure it felt inventive when it was conceived. (“And, like, these bullets will be dancing down the warehouse and we’ll be like, ‘Where is it taking them???’”) But man does it feel awkward when you watch it. Another “writerly” moment is the “family holds hands on top of car with baby monitor to get the alien signal” scene in M. Night’s “Signs.” Sometimes we can fall so in love with our creativity, we can’t see the forest through the trees. Be aware of “writerly” scenes in your script.

DON’T PUT GAGS BEFORE YOUR STORY

The reason people got so worked up about the infamous “nuke the fridge” scene in Skull actually had nothing to do with nuking the fridge. The problem was that the scene shouldn’t have existed in the first place. We could’ve easily cut straight from the warehouse to Indy’s classroom. So why, then, was this scene included? Because Spielberg (or Lucas) liked the gag. That’s the only reason it was there. And boy did they pay the price for it, because by holding the movie up for an entire 8 minutes for a silly gag that added nothing to the story and did nothing to push the plot forward, it allowed the audience to focus their attention on the absurdity of surviving a nuclear blast in a fridge. Except in rare circumstances, avoid putting anything in your screenplay that isn’t pushing the plot forward. Didn’t Spielberg learn this after his buddy’s whole fish-dragon sequence in Phantom Menace?

FORCED PLOT POINTS

Don’t force unnatural plot points on your audience. After the opening warehouse sequence, the FBI – for no logical reason – thinks Indy is a commie, which leads to an embarrassingly forced scene where Indy gets fired. If you need your hero to get fired for story purposes, GIVE US A REALISTIC REASON THEY’D BE FIRED. Don’t make up something that takes us out of the story. I’d easily buy Indiana Jones being forced into retirement because of his age (he is 65). Any time you insert a nonsensical plot piont in your story, you run the risk of breaking the audience’s suspension of disbelief. Keeping that suspension intact is essential to making the story work.

UNCLEAR ACTION SCENES

Remember how much I praised Raiders Of The Lost Ark’s action scenes. Do you remember why? Because the main character always had a clear objective! Here, action scenes are given out like past due Halloween Candy, none more random than the university motorcycle chase. On the one hand, we know Indy and Mutt are trying to escape. The problem is, we don’t know why. What do these men want? Are they killers? Are they kidnappers? Do they want the scribbled note? Do they want Jones to explain it? Is it okay to kill Indy and Mutt? Or do they need them alive? There’s an overwhelming lack of clarity in this chase, which is why it feels so pointless. To make an action scene work, make sure everyone’s motivation in the scene is clear. (as a side note: Compare how much Indiana is BEING CHASED in Skull to how much he was DOING THE CHASING in Raiders. Coincidence that the first film was more fun and exciting? Hmmm…)

EXPOSITION EXPOSITION EXPOSITION

I’m starting to think Christopher Nolan did a rewrite on Indiana Jones 4. The exposition in this script is so abundant and so lazy it’s embarrassing. How many pure exposition scenes do you remember in Raiders? Me? I remember one. The scene where they discuss going after the Ark. Here we have an exposition scene with the CIA agents after the Nuke The Fridge scene. We have one with Mutt in the cafe. We have another Mutt-Indy exposition scene after the motorcycle chase. Then we fly to the Amazon and get ANOTHER exposition/backstory scene as Indy and Mutt walk through the market. We then have another exposition scene down in the haunted cave. Usually when you have that much explaining to do in your story, it’s because you haven’t figured everything out beforehand, and are therefore forced to work it out during your script, resulting in…..you guessed: lazy overly abundant exposition.

LONG SCENES IN ROOMS IN ACTION MOVIES

This is an action movie. So can someone please tell me why there is a 15 minute scene in the middle of the movie that takes place in a tent? Putting your characters in a room for too long in any movie is a bad idea. But in an action movie, where the audience is expecting…ACTION?, a scene like this is deadly. And here’s the thing. WE DON’T EVEN KNOW WHAT THE PURPOSE OF THIS SCENE IS! CIA Double Agent Buddy comes in and yells at Indy about a city of gold or something. Russian Chick comes in afterwards (as if she was waiting for her turn – GOD THE LAZINESS IN THIS SCRIPT!) and tries to read Indy’s mind for…some reason. Then Rickshaw Jim The Mental Moron shows up to write something on a piece of paper. How many “people in a room” scenes were in Indy that went over 3 minutes? The Marion-Belloq scene maybe. But that scene actually had a purpose. Marion was trying to escape. This is just a big fat tent of non-stop exposition (and what’s even more baffling is that the point of exposition is to CLARIFY things for the audience. After this scene, we’re actually MORE confused than we were before it). The lesson here? Don’t place your action hero in a room for any extended period of time unless there’s a strong plot-related reason for it.

NEVER MAKE THINGS CONVENIENT OR EASY FOR YOUR CHARACTERS

You remember the truck chase in Raiders? Remember how Indy had to use every ounce of strength, every punch, every kick, every last brain cell (cleverly sliding underneath the truck so as not to get smushed). He worked his tail off to get control of that truck. Here? Everything, from fights to escapes are just HANDED OUT to our heroes. That 15 minute long tent scene I mentioned above? How did they get away? Shia KNOCKS OVER A TABLE! Are you kidding me? When Indy is shot into the desert with the Russian after the warehouse scene, what happens when he comes to a stop? The Russian has fallen asleep! In the back of the truck arguing with Marion? Indy KICKS the guard in the ass when he’s not looking, resulting in him passing out! But the worst is when our characters accidentally fall into a river, get dumped down three successive waterfalls, and miraculously happen to end up RIGHT IN FRONT OF THE MYSTERIOUS CAVE THEY’VE BEEN LOOKING FOR! This is a huge reason why the Indy 4 experience feels so unsatisfying. Our characters don’t earn anything. They’re HANDED everything. So please, always make things difficult for you characters. And make sure they earn their way.

So, I guess the only question left to ask is…did Indy 4 do anything right? Barely. While the goals are weak, the stakes are low, the urgency isn’t there, the plot’s unclear, there’s too much exposition, the villains suck, and the characters are barely developed, I will admit that the last 40 minutes or so were pretty exciting. Unfortunately, the reason for this had little to do with the screenplay. We, as an audience, simply knew that the story was coming to an end, and this finality, while artificially generated, gave the story some much-needed purpose. I’m disappointed with Spielberg and Lucas. I understand that there were a lot of factors at play in making this movie happen, but you’d think they’d at least put together a COMPREHENSIBLE screenplay, one where we actually understood what was going on. For some odd reason, when directors get older, they get lazier, and we got the result of that laziness here. Oh well, I heard they’re making a fifth film. Maybe someone actually plans to write a screenplay for that one?

Die Hard. Some people say Jaws changed the way movies were made. Others say Star Wars

. But an argument can be made that Die Hard

had just as much of an influence on movies as both of those films, maybe not so much culturally, but definitely in how studios approached the tent pole film. The irony, of course, is that those same studios used Die Hard as their action template without realizing what made it great. Yeah, it has splosions. Yeah, Bruce Willis was perfect casting. Yeah, the action scenes were great. But the reason Die Hard is so awesome is because of its script.

So I decided to go back to the granddaddy of contained (action) thrillers and see if I couldn’t learn a few things from it. It didn’t take long. Die Hard is chock full of screenwriting tips if you pay attention, and I’m happy to highlight ten of them for you here.

BE CREATIVE WITH YOUR TICKING TIME BOMB

Every action movie should have a ticking time bomb. But that doesn’t mean incorporating one of those cheap digital timers with a big flashing “120 minutes” on it. Instead – just like every element in your screenplay – you should look for a fresh alternative. Here, the ticking time bomb is the seven locks to the safe the computer expert is hacking. It’s a clever countdown device we’ve never quite seen before (or since) and that’s why it works so well.

SMART INCORPORATION OF EXPOSITION

Most action writers think that the blood-soaked testosterone-fueled action genre gives them license to unload exposition onto the page like a garbage truck does garbage. “The audience won’t care,” they argue. “They just want to see explosions.” Errrr…wrong! Bad exposition eliminates suspension of disbelief, which in turn makes all those “explosion” scenes less exciting. So don’t fall into this trap. Be smooth in the way you unveil exposition. Take the scene in Die Hard where McClane is in the limo. We have to get some key exposition out about John’s on-the-rocks marriage before we get to the building. A lazy writer might’ve had an unprovoked McClane start rambling on about his broken marriage. Instead, the Die Hard writers make McClane resistant, practically “forced” into giving up details to his overly nosey limo driver. In fact, the limo driver is revealing (with his guesses) almost as much about McClane’s marriage as McClane is. “You mean you thought she wouldn’t make it out here and she’d come crawling on back, so why bother to pack?.” “Like I said Argyle, you’re fast.” It’s little details like this that elevate an action script.

ONE-LINERS

Ahhh, the snappy action one-liner. An 80s film staple. But no film has ever approached Die Hard in this category. In fact, 95% of one-liners you hear in action movies these days are groan-worthy. So how does Die Hard still hold up? Simple. McClane’s one-liners stem from his situation, NOT from a writer wanting to add a funny line. When you watch Die Hard and hear McClane say, “Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker,” you genuinely get the sense that he’s trying to add levity to the situation. He’s using humor to deflect the seriousness of his predicament. In other words, he’s not a mouthpiece for a clever line thought up by a writer, which is what every single one of these one-liners has been since Die Hard came out (please see The Expendables for numerous examples).

THE BAD GUY IS A WORTHY ADVERSERY

Hans is one of the greatest bad guys of all time. How can we learn from him to make our own bad guys memorable? The key to Hans working is that he’s a worthy adversary to John McClane. He isn’t some paint-by-the-numbers thug. Die Hard is one of the few action films I can remember where they made the villain as smart as the hero. Not just on paper. But you actually SEE IT. We see the FBI cutting the last lock to the safe, the only lock Hans didn’t have access to – all part of his plan. We see Hans pretending to be a hostage when he runs into McClane. By doing this, the audience has real doubts about whether our hero can outsmart this guy, which in turn pulls us in even more.

SOMETIMES THE STORY DICTATES WE DO THINGS WE DON’T WANT TO DO

Ideally, especially in an action movie, you’d want to introduce your main character with some sort of action scene that gives us insight into who they are. Unfortunately, the direction of the story may not afford you this opportunity. In Die Hard, a lot of the key things we learn about McClane early on are through dialogue. On the plane with the other passenger, in the limo with Argyle, on his conversation with his wife when he gets there. Sure, it would have been nicer if we could’ve *shown* these things instead of been *told* about them. But the situation is what it is. You need to get your main character to the building and you need the audience to know some things before he gets there. If a similar setup is required in your movie, embrace it and do the best you can with the situation. Forced to tell something through dialogue? Make it as seamless and interesting as you possibly can and move on.

DON’T FORGET TO SHOW WHAT YOUR HERO IS FIGHTING FOR

In 110 pages of story, it’s easy to forget what your hero is fighting for. In this case, McClane is trying to save his wife. If, then, we don’t see his wife for sixty minutes, we start to forget what his ultimate motivation is. In Die Hard, around the mid-point, Holly goes to Hans and asks him if she can get a couch for her pregnant friend and bathroom breaks for the rest of the hostages. It’s a small and seemingly insignificant scene, but it reminds us and reignites our passion for why John McClane must succeed.

ONE OF THE BEST SCENES YOU CAN WRITE

One might argue that the most memorable scene in Die Hard is when Hans pretends to be a hostage. Part of the reason we love this scene so much is because it’s such a clever move by our villain. But this is actually a setup for a scene that works almost every time you use it in a screenplay: We the audience know something that our main character doesn’t – that he’s in danger – and there’s nothing we can do to help him. The tension this creates in a scene – the helplessness we feel – works on an audience almost every time, so if you have the opportunity to use it, do so. Just make sure we like your hero. Obviously, if we don’t, we won’t be too worried when he’s seconds away from getting a bullet in the chest.

CHARACTER GOALS UP THE WAZOO

There are numerous character goals in Die Hard driving the story. That’s why, even though this is just a contained action film, it feels a lot more complicated and elaborate. McClane is trying to save his wife. McClane is trying to contact the police. Hans is trying to open the safe. Hans is trying to kill McClane. Hans is trying to find the detonators. The reporter’s trying to get the story. The FBI is trying to stop the terrorists. Al is trying to help McClane get out alive. Everybody’s got something to do in this movie and whenever they achieve what they’re trying to do, the writers give them something new to do. If too many characters run out of pressing things to do in an action script, put a fork in your screenplay, cause it’s done.

THINGS GET WORSE FOR OUR HERO AS THE SCRIPT GOES ON

In every action script, you want it to get tougher on your hero the closer he gets to the finish line. McClane’s feet are heavily cut, making it difficult for him to walk. Hans figures out that Holly is John’s wife and takes her hostage, making it more difficult to save her. In the final confrontation, McClane’s only got two bullets left, making his escape unlikely. Keep stacking the odds against your hero as he gets closer to achieving his goal.

DON’T PUSH YOUR LUCK

I’ve been slurping the Die Hard kool-aid all article. In parting, I have to take one shot at the film. There’s a famous line in a Kenny Rogers song that goes, “Know when to fold’em.” At a certain point, you’ve gotten everything you’ve needed out of your screenplay. When that happens, it’s time to say “The End.” In Die Hard, there’s a really cheesy forced moment in the final scene where Terrorist #1 bursts out of the building and Sergeant Al shoots him. It was one beat too many and almost ruined an extremely satisfying ending. You always want to leave your audience wanting more. Resist that “one last unnecessary moment” and type “The End” instead.

And that’s that. Now before I leave, I want to pose a question to you guys, cause the truth is, I’m not sure what the answer is. Die Hard has one of the most cliché moments in all of action films in its finale. Bruce Willis points a gun at our villain who’s pointing a gun at our damsel in distress. Could you ask for a more obvious final scenario? And yet, I was riveted. I was terrified for Holly and I was scared that Willis wouldn’t be able to save her. Outside of the obvious, “We liked the characters,” can you explain why this moment, despite being the very definition of cliché, still worked?

And tune in next Thursday where I break down Die Hard 2 and give you 10 examples of what NOT to do in an action film.

SINCE I HAVE NO IDEA IF THE NEWSLETTER IS GETTING TO PEOPLE, I’M JUST GOING TO INCLUDE IT HERE ON THE SITE. ENJOY! AND IF YOU WANT FUTURE NEWSLETTERS, E-MAIL ME AT CARSONREEVES1@GMAIL.COM. THAT’S ASSUMING I CAN GET THEM SENT OUT!

I was talking to an aspiring writer the other day and we got onto the topic of movies, specifically what we’d seen lately. He said that he’d rewatched this old movie that both of us liked and I said to him, “Have you ever read the script for that movie? It’s even better than the film.” What he said next shocked me. “I don’t read scripts.”

I gasped and replied, “What do you mean, you don’t read scripts? Like you don’t read them that often?” He said, no, he’d read maybe three scripts in his entire life and they were all classic film scripts. “You’ve never read a screenplay that hasn’t become a movie yet??” I asked. “No,” he said. “Never.”

This wasn’t the first time I’d heard this from a writer. In fact, I once knew a writer who didn’t just *not read* scripts, he was so uninterested in doing so, he’d go on 20-minute villain monologues about how pointless (and boring) reading scripts was. And he had proof to back it up! He actually sold a screenplay! For mid-to-six figures!

How the heck did that happen? Well, to his credit, he was really good at picking high concepts and injecting GSU (goal, stakes, urgency).

But there was always something off about his writing that I couldn’t put my finger on. The rhythm wasn’t quite there. The sentence structure was slightly odd. And just the whole experience of reading his scripts felt like you were reading a “highlights reel” of a script, ” if that makes sense. His scripts never felt like true screenplays.

Not that I wish any ill will on writers, but I wasn’t surprised to hear that the writer hung it up three years later, failing to experience any more success. You can sometimes get a lucky invite into the game. But it’s hard to stay if you don’t know what you’re doing. People figure that out sooner or later.

I have no doubt that the fact this writer had never read any screenplays before hurt his writing A LOT. Let me explain why.

I’m currently working with an actress who’s writing her first screenplay. It’s a true story about the birth of a particular tech industry. One of the issues she’s running up against is explaining the complicated world of that industry which is clear to her but foreign to us. So I sent her the Sam Bankman-Fried script I reviewed the other day, which did a lousy job of explaining its industry, in order to show her how the lack of properly conveyed exposition makes it hard for a reader to follow along.

It’s only when you experience writing weakness as a reader that it clicks for you what you have to demonstrate in your own scripts. How can you possibly understand how to keep someone interested in your story if you have never read a screenplay that’s kept your interest before? How can you ever understand how to keep someone from getting bored if you yourself have never been bored reading a screenplay before? How can you understand the rhythm of a screenplay if you’ve never been subjected to good screenplay rhythm? How can you know how much information the reader needs about your world if you’ve never read a script that effortlessly disseminates a lot of information?

You can’t just answer, “I can do that because I watch movies” because you’re not yet writing for a movie audience. You are writing for a reader. A series of readers must approve of your script before it can become a movie. So you have to be hip to THAT PERSON’S EXPERIENCE, not the audience member’s experience. And believe me, it’s a different ballgame. Movies are a passive experience. Reading is an ACTIVE experience. Or, to put it bluntly: Reading is harder than watching. So the bar for keeping the person engaged is higher.

I’m not saying you need to read as many scripts as I do. But you need to read at least a couple of scripts a month. Lucky for you, I have some reading material to pass on! I’m giving you four good scripts and two bad ones. You may be wondering why I’m including bad scripts. It’s because you need to know what types of things frustrate readers. You can’t write a good script unless you’ve been on the receiving end of a bad one. Because those are the scripts that drill into your head, “I’m going to make sure I never do that myself.”

Here are the scripts. Start your reading TODAY.

GOOD EXAMPLE #1

Title: After The Hunt

Logline: A Yale professor up for tenure must navigate a rape accusation from her most cherished student against another professor, who happens to be her best friend at the school.

Why I included it: This is considered to be the best script of the year so it’s definitely one you’ll want to check out.

GOOD EXAMPLE #2

Title: The Nowhere Game

Logline: Two young women are kidnapped, brought deep into the woods, given a head start, and then hunted down by their sadistic captor all for the pleasure of the online fans of “The Nowhere Game.”

Why I included it: This is a great example of how to write a script that reads quickly. Those tend to do well with readers because readers don’t have a lot of time.

GOOD EXAMPLE #3

Title: Dying for You

Logline: A low-level worker on a spaceship run by a dark god must steal the most powerful weapon in the universe to save his workplace crush.

Why I included it: This is one of my favorite scripts from last year. It’s really fun and effortless to read.

GOOD EXAMPLE #4

Title: Anaconda

Logline: A group of 40-something friends decide to remake their favorite film, Anaconda, in the real Amazon forest, only to learn that an actual giant Anaconda snake is out there.

Why I included it: I don’t love this script. But it’s a great example of how to come up with a fresh angle on an old property that the studios might get excited about if you pitched it to them. This film is being made with Paul Rudd and Jack Black. (More details on this project later)

BAD EXAMPLE #1

Title: Return to Sender

Logline: A woman who’s moved into a new home and is buying a lot of things from a giant delivery company learns that she is being used for a new delivery scam.

Why I included it: This script only got recognition because the writer directed a short that did okay. But the feature adaptation of that short is awful. Note how boring it is. Note how the story barely moves. Note how small the story feels. It’s an exercise in how easy it is to make it nearly impossible for the reader to turn the pages.

BAD EXAMPLE #2

Title: Star Blazers

Logline: A rag-tag group of space pirates come together to travel to a mysterious planet to retrieve a technology that will help them defeat the alien presence that has annihilated earth.

Why I included it: This is an old script that Hollywood never made. You can see that there’s not a single original idea in the script. It also takes waaaaay too long for the main plot to get started, a COMMON problem I see in screenplays, especially for newer scriptwriters.

It’s fine if you dislike any of the scripts I recommended here or like the ones I didn’t. The objective isn’t to have you mirror my taste. It’s to help you develop your own. Regardless of which side of the fence you end up on, take note of *WHY* you like something or *WHY* you don’t. That way, you can apply (or not apply) that same approach to your own material.

NOW TAKING SUBMISSIONS FOR “SEPTEMBER SCENE SHOWDOWN!”

This month’s showdown is a SCENE SHOWDOWN. I enjoyed the process of posting the first five pages of the Mega-Showdown finalists. So I thought I’d capitalize on that theme this month. Hence, we’re going to have a SCENE SHOWDOWN. Your scenes can be five full pages long and not a word more. Write the best scene possible, submit it to me, and I will post the best five entries on the site. Another reason I’m doing this is so as many of you can enter as possible. You can write a scene in a single day. So take advantage of this. Help me discover a writer who’s ready to blow up!

For the submission, it’s going to be a little tricky, cause it’s hard to write a title or a logline for a single scene. But the good news is, I’m going to read every scene that’s submitted. And I’ll be choosing on strength-of-scene rather than the title or logline. So do your best. Also, I’m going to give everyone 30 words to prep the scene if they want to. So, here are the submission details:

Title

Genre

Logline

Up to 30 words to prep the scene

PDF of scene (up to 5 pages long)

Send to: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Deadline for entries is 10pm Pacific Time, Thursday September 26th!

AROUND TOWN

Mega-Showdown Winner, “Bedford” – The Scriptshadow Mega-Showdown winning script won me over just as it did the readers. It is a taut contained thriller in the vein of The Vast of Night. But it stirred quite a bit of controversy in the comments, with a lot of readers claiming it’s more of a stage-play than a film, since the majority of it takes place in one room and focuses on a single character. If the script were to be filmed, they argued, it would be boring because there’s nothing cinematic about it. It’s the age-old dilemma every aspiring screenwriter faces. The best way to get the most interest is to write something contained and low-budget. However, by doing so, you risk writing something static and boring. I, personally, think you could make a cool movie out of Bedford. Keep the camera moving when possible. Maybe get the hero out of the control tower a couple of times so that the location doesn’t get too stale. It was fun to see all the responses to the script. We haven’t had that spirited of a discussion about a screenplay in a long time. You can read the script for yourself here then head over and read my review!

Weird Anaconda Reimagining Somehow Going Forward at Sony – When I read this Anaconda reboot script, I thought it was a fun experiment but, by no means did I think they were going to make it. It was too weird – like something a couple of stoner college kids would write in between parties on Spring Break. But guess what? Sony’s actually going through with it! They’re signing Jack Black and Paul Rudd to play the leads, which certainly makes the project more enticing. For those who don’t know, the new Anaconda movie is going to follow a group of former aspiring filmmakers who loved the original Anaconda so much, they head to the jungle to film a low-budget version of the film in the hopes of selling it to Sony. Except they quickly learn that the giant anaconda snake is real! And it’s after them! Sony is obviously trying to do what they did with the Jumanji franchise. They took a sort-of popular movie from the past and reimagined it as a video game. So there’s some logic to the offbeat approach. But I’m just telling you – the script was really sloppy. It literally feels like the characters are making things up as they go along. If this movie is going to work, they will need to massively tighten up the story. Cause it’s a loosey-goosey premise as it is. When you add a casual narrative to a loosey-goosey premise, it has the potential to become a “What the fuck did I just watch” movie.

Weird Anaconda Reimagining Somehow Going Forward at Sony – When I read this Anaconda reboot script, I thought it was a fun experiment but, by no means did I think they were going to make it. It was too weird – like something a couple of stoner college kids would write in between parties on Spring Break. But guess what? Sony’s actually going through with it! They’re signing Jack Black and Paul Rudd to play the leads, which certainly makes the project more enticing. For those who don’t know, the new Anaconda movie is going to follow a group of former aspiring filmmakers who loved the original Anaconda so much, they head to the jungle to film a low-budget version of the film in the hopes of selling it to Sony. Except they quickly learn that the giant anaconda snake is real! And it’s after them! Sony is obviously trying to do what they did with the Jumanji franchise. They took a sort-of popular movie from the past and reimagined it as a video game. So there’s some logic to the offbeat approach. But I’m just telling you – the script was really sloppy. It literally feels like the characters are making things up as they go along. If this movie is going to work, they will need to massively tighten up the story. Cause it’s a loosey-goosey premise as it is. When you add a casual narrative to a loosey-goosey premise, it has the potential to become a “What the fuck did I just watch” movie.

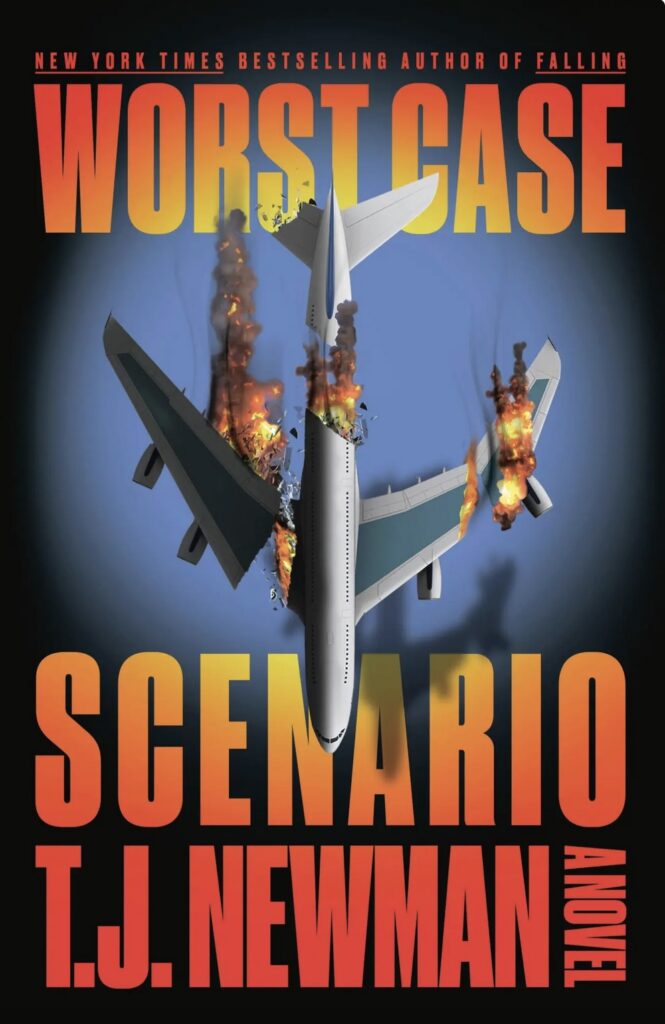

Worst Case Scenario – TJ Newman is back with her third big thriller book. For those who don’t know Newman’s journey, she’s the flight attendant who wrote a book in between serving passengers on transatlantic flights. She then sent her first book, Falling, to 40+ agents, all of whom rejected her. Until finally she landed one, which helped her secure a million dollar movie deal for the book. What I like about TJ is that she writes these high concept ideas as fast-moving thrillers. In that way, they mimic screenplays. This allows for quick and dirty reads that present the core concept in a digestible way. In other words, they’re easy for a producer to say ‘yes’ to. Newman said this idea – a plane crashing into a nuclear reactor – came to her because, in a search for story ideas, she asked all the pilots she knew what their biggest fear was. One of them said, that a terrorist not only hijacked their flight, but flew the plane into a nuclear reactor. Pro tip: Be ready for success like TJ Newman was. She wrote her second novel QUICKLY and, therefore, was able to take advantage of the buzz surrounding her first sale, grabbing a second flashy movie deal with “Drowning.” And she wrote this third book pretty fast as well. If you wait too long and a movie falls apart before production or the movie gets made and it sucks, you lose all that buzz, which makes it much harder to sell stuff. But if you can write more books and scripts BEFORE any of that happens, you can really cash in. That’s what Newman did.

Jurassic World Rebirth – Things have gotten so competitive in the content space that studios aren’t even waiting the minimum amount of time to reboot franchises anymore (that would be 5 years). They’re now trying to do it in 3 years! The last Jurassic World movie came out in 2022. This new one, starring Scarlett Johanssen, will come out in 2025 (funny enough, the setting for the new story will take place 5 years after the previous film). Here’s the premise: The three biggest dinosaurs have a genetic secret that will help save a bunch of human lives. So Scarlett must travel across the world and get DNA samples from these three rogue dinosaurs. But, in the process, she gets stuck on an island with them. Let’s be honest – it’s an uninspired, borderline clumsy, premise. You would think that if they were rushing to get this made, they’d have something sexier. But this feels like par for the course. It is interesting to note how Anaconda is rebooting itself in a risky way whereas Jurassic World is taking zero creative risks. There is a mystery as to what is on the island in this movie. It could be the long-rumored “Dino-humans” that found their way into earlier Jurassic Park sequel drafts. But I don’t think Dino-humans are going to cut it for audiences. This feels like a cash-grab and the stench of that greed is so thick, I’m anticipating nobody showing up for dinner.

Don’t Forget to Grab The Greatest Dialogue Book Ever Written!

This Labor Day, it’s time to finally improve your dialogue. I keep running into amateur scripts with weak or average dialogue. My dialogue book gives you specific instructions on how to add more flavor to your characters’ interactions. It’s just $9.99 and has over 250 dialogue tips in it. That’s 240 more than anybody else is going to give you. What are you waiting for!?

Book Review – Caught Stealing

Genre: Crime/Thriller

Premise: A baseball-loving lowlife agrees to cat-sit for his neighbor, inadvertently getting pulled into the seedy underworld of New York crime, where people will do anything to get the money they deserve.

About: This is uber-auteur Darren Aaronfsky’s (The Whale, Requiem for a Dream) latest project. It has a flashy cast list that includes “Elvis,” wannabe Oscar-winner Austin Butler, House of The Dragon’s Matt Smith, and borderline Hollywood royalty, Liev Schrieber. The writer, Charlie Huston, has written six books and tons of comics.

Writer: Charlie Huston

Details: about 250 pages

It’s always interesting to see which projects great directors, actors, and producers choose, as it’s a window into their decision-making process and, therefore, knowledge you can use if you ever get an opportunity to pitch them yourself.

But, with this one, there isn’t a lot of guesswork as to why Aronofsky chose it. His previous movie was all about a man glued to his chair (The Whale). This movie is all about a man who never stops moving. Whether Aronofsky was conscious of that radical shift or not, he obviously wanted to go in the opposite direction of “guy on chair.”

New York City. Hank is a professional drunk. He used to have a future as a major baseball prospect but nowadays, in his 30s, his only proximity to baseball is betting on it. After a particularly gnarly night of drinking, Hank is asked by his apartment neighbor, Russ, to take care of his cat while he’s gone. Hank thinks nothing of it and agrees.

The next day, after he feeds the cat, he moves the cat litter box and finds a key taped to the bottom of it. Hank shrugs and heads out to drink again. When he gets back, some Russian guys want to talk to him. They explain that they’re looking for his neighbor, Russ, and they really REALLY need to find him. Hank tells them the truth – he doesn’t know where his neighbor is or when he’ll be back – and they begrudgingly leave.

But the next day, the Russians come back, and this time they’re a lot less kind. They know Hank knows where Russ is as well as where the key is. Then they beat him up badly to let him know how much they need that key. Hank says fuck this and calls the cops. A policeman named Roman comes over. Asks him a bunch of questions. Roman says be more careful. And leaves.

The day after that, two large black men in cowboy attire show up and THEY want to know where the key is. They drive him around and rough him up in order to let him know how much they need that key. As soon as they’re gone, the Russians come back to beat Hank up some more. But this time, they bring Roman with them. Yes, Roman the Cop is working with the Russians.

Fun and games are over. If Hank doesn’t give them the key, they’re going to kill him. Okay fine, Hank says. I’ll get you the key. There’s only one problem – Hank hid the key when he was blackout drunk. So he doesn’t remember where it is. His best guess is at the bar he always hangs out at. But telling Roman that is a big mistake. They all head there and Roman’s men mow down everyone at the bar when they don’t offer up access to the key. This makes Hank the most wanted man in New York.

Just when things can’t get any weirder, Russ returns, finally providing clarity to the key’s importance. That key is for a storage unit that contains 4.5 million dollars. Hank will have to figure out how to push Russ out of this equation, get the money back to the bad guys so they’ll leave him alone, and oh yeah, get the cat back from Roman. Spoiler alert. IT’S NOT GOING TO BE EASY!

The one thing I’ll give Caught Stealing is that, once you read it, it’s impossible to get it out of your head.

It’s one of the most raw, visceral, intense, violent, things I’ve ever read. And it isn’t just the 50,000 punches thrown that you feel. It’s the limitless amount of alcohol being poured down our hero’s throat. It’s the devil-like screaming at Hank from every character he encounters. Even the anguish in this book feels like physical punishment.

But the story has a pretty glaring weakness. And while I believe that Aronofsky is the director best suited to tackle this weakness, I’m not convinced he can overcome it. That weakness is that the story is led by one of the most passive characters I’ve ever come across.

60% of this story is Henry getting his ass handed to him. He’s a punching bag. Again. And again. And again. And again. And again.

I suspect that’s the point. There’s some sado-masochist thing going on with Aronofsky where he wants to show someone get relentlessly beat up for 2 hours. I just don’t know if audiences are going to be able to handle it. Cause it’s so uncomfortably relentless!

But the passivity really bothered me. I’m trying to think of movies that have attempted this before. There was Equalizer 3. Denzel’s character sat back and waited most of the movie. But that was a unique situation in that we knew, from his two previous films, what he was capable of and that it was only a matter of time before he beat some ass.

And then there was Fury Road, where Mad Max gets thrown on the front of a truck for the first 45 minutes and doesn’t do anything. But he eventually got out and began kicking ass.

While it’s true that, once the midpoint hits, Hank starts becoming more active, I’m not sure it made up for the first half of the movie where the dude was just thrown around like a rag doll for an hour. I want you to imagine watching a friend of yours get beat up for 2 straight minutes. How painful would that be to watch? NOW MULTIPLY THAT BY 30! That’s what we see Hank go through.

I will say that we’re all looking to give audiences something fresh – something they haven’t seen already. One of the best places to do that is in your set pieces. If you can come up with three memorable set pieces, you’ve probably written a really good movie. And while there’s nothing outwardly original about the set pieces here, the sheer magnitude of violence on display acts as its own set piece. It’s very much “Resevoir Dogs ear-cut-off scene.” But imagine after that scene was over, you got another ear-cut-off scene, and another one, and another one. At what point, as a viewer, do you surrender!??

In that sense, Caught Stealing makes me think of early Quentin Tarantino with a healthy dose of Fight Club mixed in. I mean the budget for this film is going to see a quarter of it spent just on the Foley artists crafting the thirty-some variations of the sounds of skulls cracking.

Just like all of Aronofsky’s movies, when you see the trailer, it’s going to be different. You will note how you have not seen a movie like this before. Even Fight Club and Reservoir Dogs are not as violent as this film. So it’s going to stand out. But will that lead to people wanting to see the movie? I don’t know, man. It’s a tough call. I’m emotionally spent just reading it. I can only imagine the toll it will take on me watching it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: We talk a lot about the midpoint shift in a story. It’s the thing you use to create a different SECOND HALF of the movie that doesn’t feel like the first half. Here, we have a very prominent midpoint shift. Russ (the neighbor), the one who’s responsible for all this, returns. So, whereas, before we had zero knowledge of what was going on, Russ’s entrance allows us to have ALL THE KNOWLEDGE. This changes everything for our hero and how he approaches the problem.

So, when I first started consulting on screenplays, I thought I had this revolutionary idea. I would create a real-time chart that would show the writer EXACTLY how interested I was at each point in their screenplay. Every 5 pages, I would mark on the chart, from 1-10, what my current interest level was.

The idea was that the writer could visually pinpoint the exact moments in the story that needed work. This is how I imagined a typical screenplay might look…

But I very quickly learned that that’s not how consultation scripts charted. The large majority of them would start out at around 6 or 7, sometimes 8. Then around page 15, we’d be down to 6. Page 20, down to 5. Page 30, we’re at 3. And then, the rest of the script would hover around 3 or 2. In other words, the majority of the consultation scripts I read looked like this…

I won’t even get into how demoralizing this was for a writer to receive feedback like this. Who’s going to be excited to jump into a rewrite with feedback that not only cognitively tells you your script is a disaster but VISUALLY throws it in your face as well!

So I dropped the visual consultation method.

But important lessons were learned. Two actually. 1) Most scripts go downhill quickly. 2) When a script falters, it rarely recovers.

If you know these things – which you now do! – you can work to make sure they don’t happen to you. You see, what these disastrous chart results kept reinforcing to me was how important the first act was. The first act is the foundation of your entire story. The more solid that foundation, the more likely you’re going to be scoring 8s and 9s the rest of the script as opposed to 2s and 3s.

So we have to then ask: What does a strong foundation look like?

In the world of screenwriting, it comes down to nailing five key things.

- Create a goal that propels the story through the second act.

- Create a character who we want to root for.

- Create a character who’s battling something internal that they must overcome by the end of the story.

- Establish stakes that feel important.

- Have a real plan for your story.

Let’s look at these five things individually.

Create a goal that propels the story through the second act.

A lot of writers don’t set their story up to succeed because they head into their second acts with barely any steam. A good goal THRUSTS us into the second act. The more robust the goal is, the longer it’s going to carry us through that act. Goals are usually born out of problems. Take the most recent box office king, Alien: Romulus. The main character, Rain, is desperate to get to a planet with a sun. But she’s stuck here due to her work contract. That’s the PROBLEM. When her friends offer her a chance at a cryo bay to help her get there, she joins them to go and retrieve it (GOAL).

Create a character who we want to root for

If we don’t want to root for your heroes, it doesn’t matter what else you do. Your script will almost immediately plummet to 2s and 3s the whole way through EVEN IF your plot is decent. The best ways to make us root for someone are by making them likable or sympathetic. And you can supercharge characters by making them likable AND sympathetic. A recent movie that showed us how effective this is is Deadpool and Wolverine. Deadpool is both likable (he’s funny) and sympathetic (he’s lost his purpose in the world and needs to get it back). Wolverine maybe isn’t the most likable guy. But he’s definitely sympathetic (he’s responsible for destroying his entire team back in his world).

Create a character who’s battling something internal that they must overcome by the end of the story

This is pivotal once you get to the second act. Because if you only give us a likable character and a goal in your movie, you get an Adam Sandler flick. Adam Sandler movies are fine. But there’s a reason they feel like empty calories. There’s no depth to them. This rule gives you that depth. Either give your hero a conflict they’re dealing with internally (maybe the death of a loved one that they haven’t properly gotten over) or a flaw (selfishness, stubbornness, arrogance). You do this because, throughout the second act, you need to be putting your hero into scenarios that challenge these things that they’re internally battling. For example, the hero might come face to face with the person who’s responsible for the death of the family member they’re mourning. By having these internal battles, the scenes will have more depth to them.

Establish stakes that feel important

Have you ever been watching a movie where you’re about 45 minutes into it and you think to yourself, “I do not care about ANYTHING that’s going on right now.” This often means the stakes that were set up in the story are too low. I read this consultation script once where a 20-something guy came back to his hometown for a weekend and went around and talked to a bunch of old friends. I got into a spirited discussion with the writer about how low the stakes were. There was one storyline in particular that drove me crazy. The main girl in the story… he didn’t even like her. She was the ONLY thing the story could’ve built stakes around – if he had always loved this girl and this was his only chance to get her, at least you have SOMETHING going on. But the writer was adamant about making the script feel “real” and I was trying to explain to him that true reality is boring. Movies are about the bigger moments in our lives. Movies, ideally, are covering the single most important moment in your hero’s life up until this point. That requires high stakes. So whether you’re writing a big Hollywood movie or an indie flick, make the stakes as high as you can relative to the situation.

Have a real plan for your story

This is the most important tip of them all. You need to go into your script with a plan. Not just a plan for how to get through the first ten pages. Or the first act. But a plan to get through the ENTIRE SCREENPLAY. The main reason scripts fall apart in the second act is because the writer never had a plan. They knew how it was going to start and they *hoped* they would figure things out along the way. That is a deadly strategy if you’re a screenwriter and almost surely will lead to failure unless you’re committed to writing 20 drafts, giving you ample time to clean up the weak foundation you built your story on. If you don’t know how to plan, go to Amazon and order a copy of The Sequence Method. It’s the best screenwriting book for how to plan out an entire screenplay.

One screenwriting tip I’ve heard a ton over the years is that the key to a great third act is a great first act. But the truth is, the key to a great second act AND third act is a great first act. That first act REALLY has to be solid in setting those key things up. And it goes without saying that you come into your screenplay with a good concept. Cause if your concept is weak, these five tips won’t help you much!

I consult on first acts. So if you want me to check out your first act and tell you if it’s working, I can do that for $150. And if you want a full-on script consultation, I can give you a $100 discount (I’m offering 3 of these). Just mention the “Real-Time” article in your e-mail. caronsreeves1@gmail.com