Search Results for: 10 tips from

Usually I give you guys formal screenwriting advice. But today I’m going to change things up and give you screenwriting HACKS, flashy tips that aren’t meant to guide you to the perfect screenplay so much as spice your script up. You can use two of them. You can use seven of them. It’s up to you. They will never make nor break your script. But they will HELP. Let’s begin!

1 – A concept you don’t have to defend – I see this all the time. Someone will pitch me an idea like, “A group of people trying to make it in Los Angeles endure a series of obstacles but eventually come out on top.” The writer will then immediately launch into a defense of his logline before I even say anything. “I know that sounds generic. But what it’s really about is this guy who runs an acting workshop and see…” I’m not saying the above idea would make a terrible script. If the writer knows character, it could be great. But we’re talking about hacks here, things to make your job easier. You do this by coming up with a concept that speaks for itself, that isn’t so boring that you have to defend it. “A young African-American man visits his white girlfriend’s creepy parents for the weekend, and begins to suspect that they’ve brought him here to hurt him.”

2 – At least one big character – Big characters jump off the page and get big actors attached. The kind of character you’re generally looking for here is a chatterbox with opinions who’s a little bit crazy. Juno. Ladybird. Walter from The Big Lebowski. Louis from Nightcrawler. Mildred from Three Billboards. Dixon from Three Billboards. This is one of the easiest ways to make your script stand out.

3 – A flashy opening scene – This is a TV pilot staple. But they’re available to you feature writers as well. Give us a scene that grabs us right away. If it doesn’t fit into the timeline of your story, you can make it a flash-forward. Those first 5 pages are when you’re being judged the harshest. It’s when the reader is literally thinking, “I have to read another terrible script before I can get to my own writing??” Give’em a hell of a great scene, like the opening of Scream (one of the most famous spec scripts ever), Inception, or all the James Bond films, and they’ll want to stick around.

4 – Efficient description – Keep your paragraphs to THREE LINES AT MOST. Make most of them TWO LINES AT MOST. If that scares you, good! Scripts are supposed to be easy to read. Not a chore. Learn to be a poet, to say as much as possible in as few words as possible.

5 – A small group of strong characters as opposed to a large group of average characters – Spec scripts work best with a tight cast of characters. Fight it all you want. It doesn’t change the fact that the screenwriting format LOVES setups with 4-5 main characters. Cloverfield 13, Get Out, Ex Machina, Room. All of these superhero movies with 30 characters are not spec scripts and therefore don’t require an overworked reader to keep track of all 30 people. Also, a small group of characters allows you to focus the story and give those characters more attention. So look for ideas that favor this setup.

6 – Dialogue that’s a model, not a mannequin – Mannequin dialogue is the bare essentials. It’s the shape of the human, but there’s no expression or individuality to it yet. A model, on the other hand, has a face that can express emotion. Hair that can be styled. You can dress her in something classy, sassy, slutty, distinguished, whatever you want. Here’s a scene from Three Billboards, where Dixon (Sam Rockwell) is drunk and badgering Mildred at the bar. A patron tells Mildred she sounded great in her TV interview yesterday. Here’s the “mannequin” version of Dixon’s dialogue: “Why are you encouraging her? What she’s doing is wrong.” Note how straightforward and generic that is. Anybody in the world could’ve said it. Now here’s the “model” version, which was used in the movie: “I didn’t think you came across really good in the things you were saying. I thought you came across stupid-ass.” Dixon is an idiot, a 6th grader in a man’s body. We see that here in his butchered grammar and low level vocabulary. This is how you dress up dialogue. You have it express the individual who’s speaking.

7 – An antagonist with personal motivation rather than general motivation – Marvel keeps screwing this up but there are signs of course-correction. Having a bad guy who wants to collect some item so they can harm the world is boring because it’s generic. But a bad guy who has a personal beef with the hero, as we saw with Black Panther, is interesting because it’s specific. If that doesn’t work, consider a personal beef adjacent to your hero. This is what Spider-Man: Homecoming did. The Vulture wanted to hurt the city because they went back on their contract with him, leaving him high and dry in his career and his family. Villains with solid motivations juice a story up.

8 – One giant setup and payoff – You can have as many setups and payoffs as you like. But you need one great one. Setups and payoffs are so fun and audiences LOVE them. Unfortunately, I don’t see as many of them as I used to. The Rita Hayworth poster in The Shawshank Redemption. The snakes in Indy. The clock tower storm in Back to the Future. Where are my current setups and payoffs at?

9 – A twist ending – I hesitate to put this here but nothing affects a reader more than a twist ending they never saw coming. It’s got to make sense for the movie. But there isn’t a single device that can upgrade a script faster than a great twist ending.

10 – At least one scene you KNOW everyone will be talking about when they leave the theater – I can’t tell you how many scripts I read without a SINGLE memorable scene. You need a scene that defines your movie. Achieving this is easier than you think. Just come up with a scene idea that you know audiences will have a strong reaction to. Fish sex for The Shape of Water. The peach scene in Call Me By Your Name. Dixon throwing the advertising agent out the window in Three Billboards.

There ya go. Now go hack at it!

The biggest mistake screenwriters make in screenwriting is starting with a bad idea. Actually, “bad” isn’t the right word. Another ‘b’ word is more appropriate. “Benign.” There’s nothing to the idea. It’s empty, uninspired, boring. And yet, 90% of the submissions I get continue to be lame and lifeless. What sucks about this is your script is doomed before you’ve even written word. And I’ve watched that play out too many times, with writers rearranging words, scenes, sentences, sequences, characters, loglines, all in the hope that their “idea” will all of a sudden work.

So what is a good idea? Well, there’s some subjectivity involved, of course. But generally speaking, people know when they’ve been pitched a good idea. Good ideas feel inspired, original, and bursting with potential. On the flip side, bad ideas feel cliched, uninspired, and half-baked. That isn’t a lot to go on as those descriptors are fairly nebulous. But don’t worry, cause I’m going to give you ten tips you can use to finally start coming up with good movie ideas. Are you ready? Let’s get started.

1) Try – This may sound like stupid advice. It isn’t. I’d say that half the ideas I’m pitched are bad simply because the writer isn’t trying. You can tell they came up with the idea quickly and haven’t thought it through. An idea has to be battle-tested. It should be pitted against at least ten other ideas you’ve been working through and emerge as the clear winner. Every time you come up with an idea, ask yourself, is this an inspired idea or is it similar to other ideas out there? Movie idea generation is the most competitive arena there is. EVERYBODY thinks they have a great movie idea, which means you’re competing against billions (with a ‘b’) of ideas. If you’re not trying your hardest, I guarantee you your idea’s bad. Here’s an example of a really well thought-out idea.

Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind – After their relationship fails, a couple undergoes a procedure to have the memories of each other erased, only to realize halfway through that they made a mistake. They then must race through every memory in their relationship to avoid losing each other forever.

2) A fresh angle/take – One of the easiest ways for me to identify a seasoned screenwriter over a newbie is a fresh take on an old premise. Newbies are still in that mindset where they’re re-writing the movies they grew up on. Veterans realize that to make an impression, they must find a new way into the movies they grew up on. One of the best examples of this is Memento, which took the old noir investigative thriller and turned it on its head.

Memento – A man with short-term memory loss utilizes a system of tattooing the clues of his wife’s murder on his body to find the man who killed her.

3) Clarity – A good idea is one where all the elements come together clearly and harmoniously. The idea is simple to understand and you’re able to imagine the movie immediately. I read a lot of ideas where the writer is throwing numerous pieces of the puzzle at us, but the pieces don’t fit together. I’ll give you two romantic comedy ideas to explain what I mean, one with a clear and powerful idea, the other with a murky and cluttered one.

Pretty Woman – A buttoned-up businessman in town for the biggest deal of his life hires an unrefined prostitute to pose as his girlfriend for the week, sparking an unexpected romance.

Aloha – An Air Force pilot returns to Hawaii to oversee the launch of a top secret military satellite while attempting to reconnect with his newly engaged ex-girlfriend as well as exploring a romance with the company woman who’s been assigned to keep tabs on him.

4) A complex/interesting main character – “I’m not interested in super hero movies or high concept stuff, Carson. Does that mean I’m screwed?” No. You’re not screwed. But, if you don’t have a highly marketable idea, you better have a compelling complex-as-shit main or key supporting character. That’s because your character will now become your pitch. Therefore, if they don’t sound interesting, that means you’re not giving us a great idea or a great character. What else is left? Are you going to wow us with your deft ability to hide exposition? Nightcrawler is a good example of this.

Nightcrawler – Louis Bloom, an unpleasant sociopathic loner with a gift for salesmanship, revolutionizes the practice of nightcrawling – taping violent accidents and selling them to news shows – by risking death every night to be the best in the field.

5) Irony – Another way for you guys who hate Hollywood movies to come up with a great idea is to utilize irony. The most basic form of movie irony is to make your hero the exact opposite of what’s required of him. So you wouldn’t write a story about an atheist who starts his own atheism support group. You’d write a story about an atheist who takes a job as a Christian preacher to make ends meet. Because irony is such a powerful element in making ideas pop, it’s another easy way to separate seasoned writers from newbies.

The Social Network – An antisocial Harvard freshman with no friends ends up creating the single largest friend network in the history of the world.

6) Strange Attractor – One of you had the perfect reaction to a recent Amateur Offerings idea. The commenter, assessing an idea that sounded like every action movie ever, said that the logline was the equivalent of “beige wallpaper.” And I thought that was perfect. You want to avoid the “beige wallpaper” version of movie ideas. One way to do this is to include a “strange attractor,” which is a unique element that stands out like a red rose in a desert. Even if your idea isn’t perfect, the strange attractor will get a reader’s attention. Say you want to write a survival movie. You can write about a man stuck on a life raft after his boat sinks, which has no strange attractor. Or you can go with something like this…

Life of Pi – When a ship transferring zoo animals to a new country sinks, a young boy is stuck on a lifeboat with a dangerous tiger.

7) Ill-equipped main character – One of the easiest ways to make your idea more interesting is to include a main character who is extremely ill-equipped for the mission at hand. This will make the character an UNDERDOG, which is one of the most salable elements in idea creation. And really, this gets to the heart of what makes any story good, which is that the journey must be difficult. What better way to make the journey difficult than to make the main character as ill-equipped for that journey as possible?

The King’s Speech – The King of England, a rampant stutterer, must overcome his speech impediment to give the most important speech in history, one that inspires the world to stop Adolf Hitler.

8) A Primary Source of Conflict – Remember guys, that a screenplay is broken down into three acts. Act 1 is SETUP. Act 3 is RESOLUTION. That leaves us with one act left. Which act is that? It’s the act of CONFLICT. A movie idea without conflict isn’t a movie idea. It’s the beginning of a movie idea. One of the reasons Hancock was so forgettable was because it only ever figured out the beginning of its idea – a drunk superhero. It needed a strong conflict to turn it into a fully-fleshed out idea.

Murder on the Orient Express – When a murder occurs on an extended lavish train ride, a detective must find the killer amongst 13 suspects before the murderer strikes again. (the conflict is the detective’s investigation – that’s what will take up the second act).

9) Genre-Mixing – This is one of the oldest tricks in coming up with fresh ideas. You simply take one genre and mix it up with another one. Since most writers tend to stay in one genre lane, the Frankensteinien results of genre mixing give way to some interesting ideas. Some of the more common genres that are mixed are horror and sci-fi, comedy and sci-fi, thrillers and horror. But don’t stop there. Get weird if you want. Mix a musical with a western. Mix adventure and film noir. At the very least, you’ll have an idea that stands apart from all that cliche garbage everyone else is coming up with. And here’s a bonus tip: The less the two genres go together, the more unique the idea will be. Mixing the romance and serial killer genres, for example.

Westworld (mixes Western and Science-Fiction genres) – A robot malfunction creates havoc at a futuristic amusement park that allows its participants to live in an artificially constructed Old West.

10) Relatively High Stakes – There’s a reason I used the word “relatively” here. That’s because not every movie is about saving the universe, nor should it be. However, the importance of your hero’s journey must contain consequences relative to that journey. Otherwise your idea sounds unimportant. One of the reasons the movie “Wild” didn’t catch on was because there were no clear stakes. A girl hikes a trail to find herself. What happens if she doesn’t find herself? Err… she’s upset? The relative stakes in that movie are non-existent. The Sweet Hereafter, another character-driven indie film, was dripping in stakes.

The Sweet Hereafter – A teenage girl who survived the most horrific school bus crash in history is the key witness in a class action suit against the state, but isn’t sure she wants to tell the truth about what happened that day.

There you have it, guys! The road map to all your future movie ideas. I encourage you to practice these tips and share the results in the comments section. The readers of this site are good at explaining why loglines or concepts aren’t working. So this is as good of an opportunity as you’re going to get at practicing idea generation and receiving valuable feedback.

If you want to get my personal opinion, I charge $25 for 200 words of feedback on loglines. I also charge $75 for a pack of 5 loglines. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: “LOGLINE” to sign up. You can also hire me to consult on feature screenplays and pilots. I’ll give you $50 off with the subject header: “CONSULTATION 50.” Hope to hear from you soon!

After my last dialogue post some of you expressed the need for even MORE dialogue advice. Cue today’s post, baby! It’s time to conjure some magic dialogue spells! Shoozazah!

Remember that at the heart of all good dialogue is conflict, but more specifically some kind of imbalance in the interaction. Something is unresolved and the characters haven’t come to an agreement yet. This necessitates conversation, which is where good dialogue is born.

For example, let’s say that my girlfriend, Jane, was driving me to the airport. If we spent the entire conversation agreeing to all the things we needed to have done by the time I got back from my trip, the dialogue would be boring.

But what if last night, at 3am, I got a text from someone named “Lisa.” My girlfriend and I argued about it and left it at, “We’ll discuss it in the morning.” Here we now are, in the car, driving to the airport, and that text is still lingering. Our dialogue is going to be way more interesting cause there’s an unresolved issue dominating the conversation.

So that’s the main thing you need to keep in mind. Conflict will be at the heart of most good dialogue. Also, feel free to combo these tips up, bitches!!!

Each character should want something in the scene – This is the basic tenet for any meaningful conversation. Each person in the conversation should want something. If they don’t, they’re just babbling. And while the babbling will feel realistic at first (since that’s what we do in real life), it will quickly grow tiring, as we’ll drift further and further into aimlessness. It is sometimes okay for only one character in the scene to want something. But I’ve found that the more people with definitive goals there are in a scene, the better the dialogue gets. In the above scene, my girlfriend wants to know who the hell Lisa is and why she’s sending me a text at 3am. I, on the other hand, want to get to the airport without having to answer that question.

Contrast (character) – One of the easiest ways to create good dialogue is to place contrasting characters together. One character is selfless, the other selfish. One character is arrogant, the other modest. One character is smooth, the other a klutz. A stud, a dork. Intelligent, an idiot. The reason this works on the same level conflict does is that there’s an imbalance. Except this time the imbalance is in the characters themselves. Also of note: the goofier the movie, the further away the polarity should be. The more serious a movie, the differences between the characters will be more subtle.

Contrast (scene specific) – This is when you create contrast via a specific scenario. It doesn’t require that your two characters be permanently on opposite sides of the spectrum. Just temporarily. This could mean that one character is calm about something while the other is freaking out. One character is furious while the other is laughing. One character thinks something is a big deal while the other doesn’t think it’s a big deal at all. The opening scene in Fargo when Jerry Lundergaard walks into the bar to hire the kidnappers highlights this well. They’re pissed that Jerry’s late. Jerry believes this is incidental. That contrast leads to a scene laced with killer conflict (as the kidnappers become agitated that Jerry isn’t even acknowledging their anger).

Dialogue-Friendly Characters – No amount of dialoguing will help if you don’t have at least one dialogue-friendly character in a scene. You gotta have a character in a scene who’s witty or thoughtful or weird or manic or an arrogant prick or overly friendly or anything that necessitates an above-average output of words. It’s not impossible to write good dialogue without dialogue-friendly characters. But it’s hard.

Dramatic Irony – One of the easiest ways to write good dialogue. Place a character in a conversation where we know more than he knows. If Joe is reuniting with his high school friends in a remote cottage for the weekend and we previously had a scene showing that the friends plan to murder Joe, the dialogue is going to be great. A scene as simple as Frank (Joe’s best friend) welcoming him and showing him around the house, can result in riveting dialogue. Also, dramatic irony allows you to play around with and have fun with the dialogue! Joe: “This is going to be a memorable weekend.” Frank: “It sure is.”

Elephant in the room conflict – Elephant in the room conflict is when there’s an issue between characters that they’re not discussing. This issue then permeates whatever conversation they’re having, adding an extra layer to it. If a married couple loses a child and keeps their pain buried, they’re going to have a lot of “elephant in the room conflict.” They may be talking about taking their car in to get fixed. But you can feel that both characters have something much bigger on the brain. Elephant in the room conflict is not reserved for tragedies, by the way. Will Ferrell and John C. Reilly could’ve just had a big unresolved fight in Step Brothers and then were called in for dinner. That dinner scene will be laced with the elephant in the room, the fight they just had.

Stakes – If there are no stakes attached to the conversation, we won’t care about the conversation. I watched this awful awful movie the other day called “The Intervention.” It was about a group of friends who spend a weekend together with the plan to tell two of the friends (who are engaged) not to get married because they’re terrible for each other. So what are the stakes here? If they fail at their goal, the friends get married. SO WHAT!!! Do we care if this couple gets married or not? No. So, of course, every single conversation in the movie fell flat. Stakes are not just movie-specific, but scene-specific as well. The bigger the stakes are for a scene, the better the dialogue. Let’s take that earlier example of Jane driving me to the airport. Let’s say that now my flight is taking me to the job interview of a lifetime – my dream job. Let’s move our conversation to right outside the airport entrance. My flight is leaving in 15 minutes. But Jane wants to know who the fuck Lisa is and why she’s texting me at 3am. We argue and argue some more, and all the while that plane is getting closer to leaving. Do you see how stakes (the job interview of a lifetime) beefs up the intensity of this scene? And by association, the dialogue? This is a great segue into our next dialogue booster…

A time constraint – Just like I showed you there. A time constraint is one of the easiest ways to juice up your dialogue. Simply make it so that one of the characters has something immediate they have to get to or has to leave in a few minutes, and instantly, the dialogue takes on a whole new intensity.

Specificity Over Generalities – The dialogue should seem specific and unique to the characters saying the words. The more general the details are, the less realistic the interaction seems. There’s a moment in Annie Hall where Alvy recounts his school days. He could’ve easily said. “I hated school. Everyone was a jerk-off. Those were some of the worst days of my life.” Talk about general!!! Instead, here’s what he says: “I always felt my schoolmates were idiots. Melvyn Greenglass, you know, fat little face, and Henrietta Farrell, just Miss Perfect all the time. And-and Ivan Ackerman, always the wrong answer. Always.” Specific!

Characters should be talking to each other, not to the audience – This is one of the easiest ways to spot an amateur. Even a lot of newer professional writers do this. Don’t write scenes where characters are only saying things to convey information to the audience. My Red Widow review (in the newsletter) is the perfect example. The married couple would reminisce about when and how they first met. None of that conversation was for them. It was strictly for us so that we understood their backstory. Hence, it felt unnatural. It’s true that sometimes you will need to fit exposition or backstory into a scene. But keep massaging the scene until you can legitimately say that this is a conversation your characters would have EVEN IF there was no one watching them.

In addition to the ten tips above, there are the intangibles. Wit, jokes, bullshitting, setting up and paying off lines, the ability for a character to go off on an interesting tangent. I’ve nicknamed this skill “small talk” as it mirrors the ability to converse in real life and it’s one of the skills most responsible for your dialogue feeling natural. It is also the part of dialogue most dependent on talent. The good news is, even if you’re bad at small talk, you can still master the ten tips above and do your best to sprinkle in enough “small talk” to write solid dialogue. You may not be Tarantino, but nobody’s going to dock you points for your dialogue either.

What about you guys? Any more game-changing dialogue tips???

We’ve just watched a movie make more money at the box office than any other movie in history. There’s a movie in theaters shot by one of the world’s best directors and starring one of the best actors that has garnered multiple Academy Award nominations (The Revenant). We’re a month and a half away from two of the biggest superhero films in history, Batman vs. Superman and Captain America: Civil War.

For those who would rather view their entertainment in the comfort of their own home, Netflix has offered its customers a variety of enormously budgeted high profile shows, including House of Cards, Daredevil, and Jessica Jones. It seems wherever you go, there’s tons of entertainment to choose from.

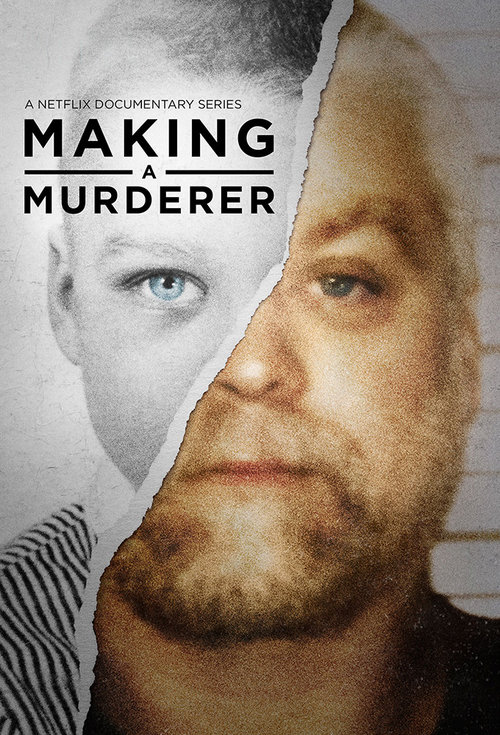

And yet despite this, when I run into people outside of the movie world, normal people on the street, they all only want to talk about one thing: Making A Murderer. It’s become such a part of the cultural lexicon that “Have you seen Making a Murderer?” is officially the new, “What’s up?”

When anything breaks out of its genre space and becomes a universally known phenomenon, every screenwriter serious about this craft need stand up and pay attention. The world is telling you what people respond to (I believe this to be true for TV, movies, songs, plays, any form of entertainment). And so today, I wanted to look at this show to see if we could glean any screenwriting lessons from it.

Before we start, however, I’ll offer my quick opinions on the show, since everybody has one. Spoilers follow throughout the post, of course. Personally, I think Steven Avery is guilty. I believe the show leaves out a bunch of crucial pieces of information on the prosecution’s side in order to make Steven a more sympathetic protagonist. And when you think about it, they had no choice. If anyone was certain that Steven committed this crime, the entire documentary implodes. We have to want to root for the guy for everything to work. The filmmakers knew this, and so strategically withheld key pieces of evidence so that we’d side with Avery.

As far as documenting a real life case where you’re supposed to be impartial, this was a slimy move. But if you’re looking at this as pure entertainment, it was a genius move, because, again, we want to root for this guy. We want to believe the system is corrupt. We want to see that system go down. And that’s the first of a few lessons Making a Murderer can teach us in regards to screenwriting.

I want to go through five storytelling lessons derived from this series that we can apply to our own screenplays, to give them a similar chance to break out and become mainstream hits.

1) The system makes you play by one set of rules, while they get to play by another (aka “corruption”) – This setup ALWAYS WORKS folks. As members of society who are constantly nickled and dimed by the system (taxes on everything, parking tickets for being a minute late to your car, police harassment), when that very system makes a mistake and doesn’t cop to it? It makes our blood boil. We want them to pay just like we’ve had to pay our whole lives. This is the crux of why Making a Murderer works. These guys screwed up by putting an innocent man in prison, and then, to avoid paying for it, they framed him for murder.

2) We hate bullies – It doesn’t matter if it’s the bully at the schoolyard or a giant corporation throwing all its legal resources to bury the little guy who’s come up with a better way to do what they do. We hate when the big guy picks on the little guy. And that’s why we react so strongly to the state bullying Steven Avery.

3) We love the underdog – We always root for the underdog. And the more of an underdog they are, the more we’ll root for them. A simple and powerful way to come up with a story is to start with a small fry being pitted against a giant fry.

4) Wrongly accused – We HATE when our main character has been wrongly accused. We want to scream out to the system, “They’re innocent!” Harrison Ford and The Fugitive started this trend back in the 90s and it hasn’t failed to deliver since. We’ll always get heated when someone who’s innocent is thrown in prison.

5) Add a twist to your murder-mystery – This is probably the most important tip coming out of this show. Murder is everywhere in storytelling. But a dead body and a few suspects is too generic. We’ve seen that setup too many times already. You have to find a twist that makes your murder-mystery FRESH. The genius of Making A Murderer is its unique twist on the genre. What if someone who was accused of murder had already spent years in prison for a crime they didn’t commit? That adds a whole new dimension to the murder, one that makes you prone to believe the man, no matter how extensively the evidence is stacked against him.

When you put all these things together, you can see why this show has taken off. For me, the first 5 episodes of the show were genius. I loved 6-8 as well. But I found myself passively watching once I got to 9 and 10. I’m a huge believer that when you hit the end of your main character’s plight, the story’s over. And after episode 8, we knew Steven Avery’s fate. The stuff with his son or nephew or whatever (the focus of 9 and 10) was never that interesting to me. He wasn’t as sympathetic of a character. I know he was taken advantage of but for some reason I didn’t care. And just from a storytelling perspective, you want to wrap up your secondary character’s storyline before you wrap up your main character’s storyline. Making a Murderer did it the opposite way, sending the show out on a whimper instead of a bang. What did you guys think?

I ain’t going to lie folks. I’m buried in Scriptshadow 250 reads. The good news is, I’ve already sent TWO scripts into the Top 25. And no, I’m not going to tell you which ones. Because I’m evil. Because I’m an evil evil man.

Unfortunately, this means I need you to do the heavy lifting today. Normally, Thursday is about me offering screenwriting tips to you. But today, you’re going to offer screenwriting tips to me, and by extension to each other.

You see, a couple of weeks ago when I was going through the Scriptshadow 250 e-mail submissions, one of you mentioned that screenplays were about characters doing bad things for good reasons. I’d never thought of it that way before but I realized that’s exactly when screenplays are at their best. Someone has to do the wrong thing for the right reason.

Think about it. If your hero has to kill a child molester to save the day, there isn’t a whole lot of drama in that. I mean, of course he does. But what if your hero had to kill an innocent man to save his son from a child molester? Now we’ve got some drama, right? He’s doing a bad thing for the “right” reason.

I get so wrapped up in my GSU universe, I forget how many other lessons and tips and theories are out there. And maybe I oughtta do more listening and less preaching.

So here’s my question. What are the best screenwriting tips you’ve learned that haven’t come from this site? What is that amazing tip that I don’t talk about here on Scriptshadow? It’s time for you to teach me something. And make sure to curate the comments by UP-VOTING your favorite tip so the best tips rise to the top.

I’m hungry for knowledge.

Feed me, Seymour! FEED ME!