Search Results for: 10 tips from

Sci-Fi Showdown is just a month away and that means you should be carving your script into shape!

What: Sci-fi Showdown

When: Entries due by Thursday, September 16th, 11:59 PM Pacific Time

How: Include title, genre, logline, Why We Should Read, and a PDF of your script

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

The most important thing when it comes to writing a science fiction screenplay is having a good concept. Since we’re well past the conceptual stage, I’m going to assume you’ve taken care of that part. This article is going to focus on everything else you can do to make your script great. So let’s jump into it!

I Need A Hero

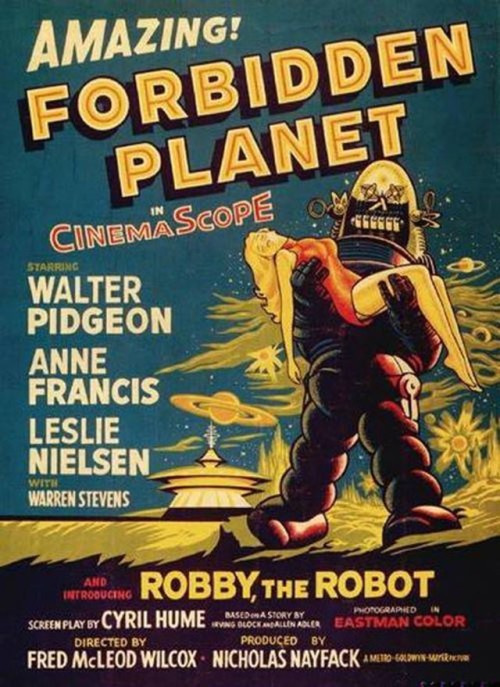

Make sure we love your hero. This is applicable to all genres, of course. But when you look at the great sci-fi films of our time, they all have characters we love. From Neo to The Terminator to Ripley to Mad Max. All of these protagonists are iconic. A specific theme running through most great sci-fi characters is that they’re underdogs. Neo is a nerdy loner hacker. The Terminator gets his ass handed to him by the newer slicker T-1000. Ripley is just some lowly consultant in a ship full of marines. Mad Max is the ultimate loner, a man without a single friend. Robocop is relentlessly riddled with bullets until there’s barely anything left of him. The character in Upgrade becomes a paraplegic.

Giving the audience an easy reason to root for your hero can do wonders. If your protagonist isn’t an underdog, find other ways to make them sympathetic. When we meet Peter Quill in Guardians of the Galaxy, for example, he loses his mother to cancer. Sympathy is a screenwriting superpower when done right.

Don’t Settle For Average

One of the big things I’m going to be looking at is set pieces. ENTIRE MOVIES have been made because someone loved a single set piece in a script.

I recently read a solid action script for a consultation. But the writer seemed surprised that I didn’t like his set pieces more. What I explained to him was that I read set pieces ALL WEEK LONG every single week, and they’re all basically the same.

There’s a lot of running. There’s a lot of shooting. There’s a lot of fighting. There’s a lot of car-chasing.

What screenwriters don’t understand is that it’s virtually impossible to make those four elements exciting on the page. Think about it from the reader’s side. Let’s say you’re writing a shootout in the streets. How can you possibly write a shootout that isn’t going to have those same repetitive beats that we’ve read a million times?

So what I’m looking for when it comes to set-pieces is CLEVERNESS or UNIQUENESS. I’m looking for a setup that I haven’t quite seen before. That’s the kind of thing that gets me excited as a reader.

Inception is a good example. A situation where the environment is rotating and time is expanding. John Wick 3 – a fight in a library where books are being used as deadly weapons. Playing a deadly game of hide and seek with velociraptors in a kitchen. Navigating the collapse of a space elevator 100,000 feet above the earth’s surface (Ad Astra). These are the types of scenes I’m going to respond to.

Nuts and bolts action scenes like motorcycle chases through cities can work on screen. BUT THEY ARE OFTEN BORING ON THE PAGE. This is why spec screenwriters have to approach their set pieces differently. Their scripts are not getting automatically greenlit. So they must come up with set pieces that don’t just work on screen, BUT ON THE PAGE. Sci-fi is the perfect genre for achieving this because you have more elements at your disposal than just guns, fists, and cars.

World Build Your Ass Off

One of the unique things about science fiction is the mythology. Because you’re creating something that doesn’t actually exist, you are responsible for constructing all of that world’s backstory and rules. If you don’t do a thorough deep dive into your world’s backstory or effectively convey your mythology’s rules, you will lose the reader.

What do I mean by ‘thorough deep dive?’ Let’s take District 9 as an example. The movie starts with a ship hovering over a city. The beginner screenwriter says, “That’s all I need to know.” The seasoned screenwriter asks, where did that ship come from? How long did it take to get here? Why did it leave its planet? What kind of planet was it? What was the environment like? Was it a cold planet? A hot one? How did that affect the aliens? Why did they decide to come to earth specifically? What do they want? Are they intelligent?

The more questions you ask, the more SPECIFICITY you build into the mythology, which allows your world to feel more genuine. Remember, GENERALITY breeds GENERICNESS. So, the more you know, the more specific, and therefore believable, your world will be. Let’s take just one of these questions to see how it can affect the story. “Why did the aliens decide to come to earth specifically?” Maybe the answer is, they didn’t. Maybe they were on their way to somewhere else, got an intergalactic flat tire, and were forced to stop at earth. That changes the mythology drastically compared to if they had come to earth to destroy mankind and take over the planet, which is how most screenwriters would’ve approached the story.

The reason you do a deep dive on the first part – the mythology – is so that you can effectively convey the second part – the rules. The more you know about the backstory, the easier it is to formulate the rules. Now, District 9 isn’t as rule-based a mythology as say, The Matrix, which requires lots of explanation. But it’s still got rules that you need to convey, such as the fact that all the alien tech is DNA encoded so that humans can’t use it.

I was developing a loop script recently and one of the questions that came up was, “Why did the loop start?” If a loop just decided to happen to, of all the people in the world, our hero, clearly something/someone made a choice to do that. Who was that someone/something? Why did they pick our protagonist? We actually never came up with a good answer. But, make no mistake, you need to ask those questions.

I can’t stress this enough. The more you know about your world, the more confident both your writing and your story will be. The opposite is also true. The less you know, the less it SEEMS LIKE YOU KNOW. And the second the reader senses that the writer is bullshitting them, they’re out. This happens ALL THE TIME WITH AMATEUR SCI-FI SCRIPTS. I know because I’ve read them all. Don’t let it happen to you.

A Sense of Urgency

Sci-Fi doesn’t tend to do well with slow narratives. It’s a genre that wants to move. Look no further than the trailer for Reminiscence. As I told you months ago, it looks slow and boring. What are all the critics saying now that they’ve watched the film? You guessed it. That it’s slow and boring. From Source Code to Terminator to Star Wars to Guardians to Fury Road to District 9 to Edge of Tomorrow… sci-fi works best with a sense of urgency. So I implore you to add a sense of urgency if you don’t already have it.

It’s true that not every story is set up to sprint. Ex Machina is a good example of that. But even Ex Machina operates within a contained timeframe – I believe that our main character is visiting the famous tech CEO’s compound for one weekend. So, even though the story takes its time, we, the audience, know the end of the journey is near. I know some of you loved Blade Runner 2049 but one of the reasons that movie only hit with sci-fi die hards and cinephiles is because there was zero sense of urgency. Don’t make the same mistake in your script. Especially if you want to do well in the Sci-Fi Showdown.

Before I let you go, let’s take a second to remember a few science-fiction movies over the last couple of decades, shall we?

Anon

The Island

Gamer

Equilibrium

After Earth

Mute

Battle Los Angeles

Space Between Us

Valerian

Life

The Darkest Hour

Ultraviolet

Jupiter Ascending

Johnny Mneumonic

Battlefield Earth

Elysium

In Time

I Am Number Four

What do all of these awful sci-fi movies have in common?

The hell if I know.

But if I had to bet, I would say that ‘writing laziness’ was a major contributor. This is a genre that if you don’t put in the hard work and make every aspect of the script as good as you can possibly make it, it will definitely fail. Assuming all the basics are in place (good concept, goal, stakes, urgency, conflict, obstacles, good dialogue, clean exposition, structure, character development) you must be creative. You must be imaginative. Know your world. Know your story. Give us scenarios we haven’t seen before. Give us someone to root for. If you do that, your script will have a chance with me and, hopefully, the rest of Hollywood.

Are you actually sending your screenplay out into the world without getting professional feedback first? That is dangerous, my friend. I can tell you exactly what script issues they’re going to criticize you for and help you fix them BEFORE you send it out. I do consultations on everything from loglines ($25) to treatments ($100) to pilots ($399) to features ($499). E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested. Chat soon!

Recently, I’ve been working on two projects. One of them you know. Kinetic. Another one you don’t. In both cases, rewrites were involved. When it came to Kinetic, the writer, Chris Dennis, took what was already a good script and did a page 1 rewrite to amp everything up several notches, turning it into a great script.

On the other project, the writer and I have been going through rewrite after rewrite for a while now – even I dusted off Final Draft and took a shot at a draft – and not getting anywhere close to what we think the potential of the premise is.

And that’s been kind of a mindf&%#. Why is it that with just a single rewrite, one script becomes so much better? Yet with the other script, it feels like we’re going in circles? So I sat back and I thought about it for a long time.

Finally, the answer came to me.

The main character.

The main character in Kinetic is awesome. He’s this tough man’s man with an inner rage he struggles every day to keep a lid on. He’s the middle America version of the Hulk. He’s just a really captivating character you want to watch. You’re always curious to see what he might do next.

The main character in the other script is your classic ‘safe protagonist.’ He’s a normal dude. He’s grounded in reality. There isn’t anything about him that stands out, that’s memorable.

This is an EXTREMELY COMMON problem in screenwriting. I pointed this out in my review of the Martin Scorsese, Eric Roth, Leonardo DiCaprio collaboration – Killers of the Flower Moon. That main character was just like this main character. Safe. Grounded. Nothing about him stood out. And, what do you know, Leonardo DiCaprio eventually decided not to play the part for that reason (he went over to play the more interesting bad guy instead).

All of this led me to realize that if a script isn’t working and you haven’t yet figured out a strong main character, it doesn’t matter how many times you rewrite it, it’s not going to work. Conversely, when you have a great main character, you can do a page one rewrite on everything else, and because your main character is so awesome, it still works.

That’s why Chris Dennis was able to rewrite an entire screenplay in 45 days and actually improve the script. Cause the hero, Clay, was so awesome.

Now before we get to the solution here, let’s first acknowledge why this happens. The main reason is because it’s hard to write a movie with an extreme protagonist. There has to be some level of “grounding” when it comes to your main character so that they feel realistic and audiences can empathize with them. And also so the journey itself feels grounded in reality.

It’s the difference between making Phil (Bradley Cooper) from The Hangover your protagonist versus Alan (Zach Galifianakis). Phil needs to be the anchor of the movie. That means he can’t fly too high. Meanwhile, since none of the emotional core of the movie rests on Alan, he could fly off to freaking Mars if the writers wanted him to. And we actually saw what happened when Alan became a lead character because they did it in Hangover 3. And the movie was terrible.

So I understand why this mistake is made as often as it is. The more exaggerated, exotic, eccentric, crazy, weird, your hero is, the harder it is to ground them. So most writers stay closer to the “everyman” option, hoping that creating a “real” person will automatically make the audience empathize with them. More often than not, however, it just leads to a boring character.

So how do we reconcile this? Well, there are three main categories you should be considering when building your hero. They are: INTERESTING, LIKABLE, SYMPATHETIC. You want to come up with some combination of traits that fit into these three categories. And the good news is, you can pack as many as you want into your character. You don’t have to stop at one or two or even three.

With that in mind, here are 10 traits you can add to your hero to make them more interesting, more likable, and more sympathetic.

1) Give your hero a vice they can’t control (Interesting) – In order to make characters interesting, you usually have to lean into negativity somewhere. That leads to conflict, which is what makes the character come alive. Like I was talking about above, for Clay in “Kinetic,” his vice is rage. It’s deep within him. He must battle to keep it bottled up every day. With Jordan Belforte in The Wolf of Wall Street, it’s excess. Drugs, alcohol, women. He needs it all the time. To understand how effective this is, imagine The Wolf of Wall Street if Jordan didn’t have an excess problem. I’m guessing the movie would’ve been pretty boring.

2) Make your hero really good at what they do (Likable) – This is a major reason why John McClane has become an all-time classic hero. He was a really really really good cop. He was always ahead of the bad guys in Die Hard. For more modern examples, check out John Wick and Ryan Gosling’s character in “Drive.”

3) Bully your hero (Sympathy) – One of the easiest ways to make someone feel sympathy for your hero is to have someone else hurt them. It’s even more effective if your hero isn’t physically or mentally capable of fighting back. This is the very first thing they did in “Joker” to make you like Arthur Fleck. They had a group of teenagers steal Arthur’s clown sign then beat him up.

4) Have your hero be kind to others (Likable) – This may seem obvious but if you need a “straighter” character and you’re worried about them being too bland, this is a good trait to add because it makes the character very likable. This is a big reason why Forest Gump was so popular. He was one of the kindest protagonists in history. If you want to go back even further, check out George Bailey in It’s A Wonderful Life. They may never make another character as kind as George Bailey.

5) Make your hero a little bit unstable (Interesting) – Again, when it comes to making your hero interesting, you have to lean into the negative. And a popular way to create interesting characters is to make them a little bit unstable. Like Lou Bloom in Nightcrawler. Sara Connor in Terminator 2. Cassandra in Promising Young Woman. The reason these characters work is because they keep the reader guessing. If someone’s unstable, you never know what they’re going to do next.

6) Have your hero save the cat (Likable) – Have your hero do something nice for someone early on. The audience forms their opinion quickly with characters. So what you show them do early has an outsized effect on how they’re perceived.

7) Give your hero someone to love (Sympathy) – I want you to imagine a psychopathic serial killer. Do you have any sympathy for them? I’m guessing not. Now I want you to imagine a psychopathic serial killer who loves his daughter more than anything in the world. Now do you have sympathy? You may be conflicted but you definitely have more sympathy than you did before. That’s the power of giving your hero someone to love. We like people who care about others and love people who will do anything for their family.

8) Make your hero an underdog (Likable) – The underdog is one of the more guaranteed ways to make a hero likable. Slumdog Millionaire Moneyball. Rocky. The entire family in Parasite. There’s one catch to this though. The hero must be active in trying to succeed. An underdog doesn’t work if they’re not trying to change their situation.

9) Make your character a little bit of an asshole (Interesting) – This is a dangerous one because if you go to far, you get the dreaded reaction of, “I never liked the main character.” So there’s a large emphasis placed on the “a little bit” part of this advice. Tony Stark is a little bit of an asshole. Starlord (Guardians of the Galaxy) is a little bit of an asshole. The idea is to have fun with it and not emphasize the “asshole” part too much. A reason I think this works is because we’re all kind of tired of having to be so polite in society. Watching guys like Stark and Starlord be kind of a dick stirs up a bit of wish fulfillment in us.

10) Make your hero very very very active (Sympathy, Likable) – Audiences absolutely LOVE characters who doggedly pursue their goals. From Indiana Jones to Clarice to Erin Brokovich. More recently you have John Wick, Robert McCall (Equalizer), and Howard Ratner (Uncut Gems). People like people who go after things in life. It’s no different in the fictional world of movies.

Keep in mind that every movie and every main character will have different requirements. Therefore, certain traits won’t work on certain characters. For example, the way that the story in JoJo Rabbit unfolds doesn’t allow for our main character to be very very very active. There’s more introspection. There’s more character exploration. So you don’t want to try and fit square pegs into round holes. Only add a trait if you believe it works for your character in your particular movie.

Good luck and I would absolutely LOVE to hear your tips for creating a more likable, more interesting, and a more sympathetic character in the comments!

When I heard that Searching was a good movie, I was skeptical. A feature-length mystery told on a computer? Stuff like this always sounds good in theory. But when you get into the writing process, the scale of just how difficult it is becomes apparent. Even the simplest moments can be hard to work out. For example, let’s say your hero has to go to someone’s house and confront him. In a normal movie, you just write the scene. But in a gimmicky computer-only movie, you must construct the whole thing through this artificial lens of “reality” seen through the eyes of computers. So what’s your hero going to do? Show up with an iphone in his hand and record the whole thing himself? Why would he do that?

One of the things I’ve become extremely appreciative of in screenwriting over the years is authenticity. As long as a scene feels genuine and truthful, I’m invested. The second the writer starts constructing artificial reasoning into the plot beats, I check out. This is one of the reasons found-footage died. The grandfather of the genre, Blair Witch, made sense in that the group was documenting their search for a legend. But as found footage was forced to get bigger, writers had to work harder to justify why people would be holding cameras in situations. I mean, if you’re writing the found footage version of Die Hard, why would John McClane be holding a camera up to tape Hans while Hans held John’s wife hostage? Yet these were the kinds of scenarios found footage was asking us to buy into.

So I was shocked that Searching not only made all of its artificial beats plausible, but used its unique medium to improve those beats. There’s a moment in the film where the dad is convinced one of his daughter’s friends is responsible, so he confronts him at a movie theater and punches him in the face. Again, you can’t just show this scene like you would in a traditional movie. So, instead, we see the scene through a teenager at the scene who recorded it on their phone and uploaded it to Youtube (“Crazy Dad Theater Attack”). But what’s really amazing about this movie is that it’s got the tightest screenplay I’ve seen all year. There isn’t a single wasted moment. And what’s most surprising is that despite its cutthroat pacing, it still manages to pack an emotional wallop. Amazing character development AND great plotting? How often do we see that these days? Here are 10 screenwriting lessons to take away from Searching…

WARNING: LOTS OF SPOILERS BELOW (Searching is available to rent. I suggest you watch it before reading the below tips)

1) A little emotion early can go a long way late – A lot of people will leave this movie talking about its unique form of storytelling. But Searching’s secret sauce actually occurs during its first five minutes. It’s here where we see, through pictures, video and e-mail, how David loses his wife (and Margot, her mother) to a two year battle with cancer. Searching would’ve been a decent film without this scene. But it becomes a great one with it. Connecting these two through that devastating loss makes us root a million times harder for them to reunite.

2) When writing a mystery, create a character that the audience is convinced did it, then later on, clear that person – This advice is as old as the mystery, but it still works great. Writers Aneesh Chaganty and Sev Ohanian make sure to construct the brother in such a way where we know he did it. Hell, I was 90% sure he did it. If you can successfully trick the audience into believing this, later on, when the character is cleared, it leaves us floating in space, unsure of everything we thought we knew. As a reader/viewer, that’s exhilarating. Because now anyone could be the killer. And we have to read on to find out who that is.

3) The sweet spot for an inciting incident is page 15 – The “inciting incident” is when the official “problem” arrives, the thing that turns your hero’s life upside-down. In Searching, that’s when Margot goes missing. And it happens at exactly the 15 minute mark. You can certainly have your inciting incident occur sooner. Some writers put it as early as page 1 (10 Cloverfield Lane would be an example). But the reason page 15 works best is that it gives you 15 pages to establish your characters. This is important because why would we care about someone’s problem if we don’t know anything about them?

4) In mysteries, you need a, “Okay, here’s what I have so far” character – In a mystery, your hero will be coming across a lot of information. It’s important then, that every once in awhile, they share where they’re at with the reader. The best way to do this is to create a character specifically designed to convey that information – the “Okay, here’s what I have so far” character. In Searching, that character is the brother. David periodically checks in with him via Facetime to tell him (and by association us) everything he’s got, as well as get feedback on what he should do next.

5) Create mini-movies within the movie – A script can seem endless when looked at from afar. How does one come up with 100 straight minutes of a guy looking for his daughter? You come up with it by chopping your script down into smaller goal-driven movies, then playing those mini-movies out for 10-15 minutes at a time. After David connects with Detective Vick, one of the first things she says is, “I need to know everything I can about Margot’s friends. Can you help me with that?” Bam: Just like that, we have a mini-movie. The next 10 minutes are dedicated to David calling and talking to Margot’s friends, trying to learn everything he can about them and how they’re associated with Margot. Amateur screenwriters don’t know how to do this, which is why their scripts feel so scattershot and unfocused.

6) Position the real killer early on as a hot suspect, then clear them – I actually learned this by watching Investigation ID shows. What you do is you focus on a hot suspect. Here, it’s Fish_N_Chips, a girl Margot talks to online a lot, but who she’s never met in real life. David goes through their YouCast archives, and the girl definitely seems suspicious. However, when Detective Vick goes to check her out, she comes back with the frustrating news that the girl has an airtight alibi. — But here’s the trick to making this work. By writing the person off so early, we forget about them. That way, when they reemerge late, we have a big “oohhhhh yeahhhhh” reaction due to the fact that we knew, just KNEW, that that girl was suspicious. This is so much better than what lazy writers pull – which is to pluck a random killer out of thin air at the last second.

7) Exploit what’s unique about your story – One of the first things you should ask yourself when you’re writing something is, “What’s unique about my story?” Once you know the answer, you can look for ways to exploit it. Since a lot of Searching takes place via text messages, it allows the writers to occasionally get inside David’s head via deleted messages. David will want to say something… “Your mom would be proud.” Which we see him write out. But then he changes his mind and deletes the text before sending it. It’s this clever little way to let us know what the hero is thinking.

8) Be clever in how you reveal exposition – One of the easiest ways to determine where a screenwriter is in their journey is to see how they deal with exposition. The more on-the-nose, overwritten, and dialogue-driven exposition is, the newer the writer. The more clever the exposition is exposed, the more advanced they are. Searching has one of the best uses of exposition I’ve seen all year. At one point, David must go into his wife’s old computer profile to find information about Margot. He opens it up and the first thing he sees is a pop-up: “You have not run Norton Anti-Virus in 694 days.” And just like that, we know how long his wife has been dead.

9) Killers working together give you a huge advantage over the reader – If you have two killers working together, it’s way easier to throw readers off the scent. And since tricking a reader these days is super-hard, the dual-killer setup can be a secret weapon. What we eventually learn in Searching is that Detective Vick’s son is the “killer.” Therefore, she’s trying to cover up what he did. Remember Fish_N_Chips? The early primary suspect? It turns out that was Detective Vick’s son. Because Chaganty and Ohanian were using a two-killer setup, they were able to have Detective Vick “visit” Fish_N_Chips and confirm that “she” had an alibi. Without the two-killer setup, explaining why Fish_N_Chips was let go early would’ve been impossible.

10) Make hard-to-believe plot points easier to believe via set-ups – In almost every screenplay, there will be a few plot points that are hard sells. The best way to deal with these is to SET THEM UP EARLY ON. If we feel like something’s already been established, we’ll be more likely to go with it. Searching has a hard-to-believe plot point in its third act – a live-cast of Margot’s funeral. Aneesh Chaganty and Sev Ohanian take care of this by having the Live Cast company contact David earlier in the script, when his missing daughter story has gone national. They’re basically a business looking to make a sale. David tells them to fuck off. “SHE’S NOT DEAD!” More importantly, the brief interaction makes the reemergence of the Live Cast more believable in the third act.

TIP 1: Have at least one character in your script who experiences a major transformation.

TIP 2: Beware “I can do that too” writing, where you’re basically rewriting your favorite films.

TIP 3: Avoid “dirty” pages. These are pages with a lot of dashes, ellipses, bolded or italicized text. Keep things clean and easy to look at.

TIP 4: There should always be a sense of doubt that your main character will succeed. If there isn’t, why would we care?

TIP 5: For every solution you provide your character, make sure it leads to a new problem.

TIP 6: If a scene is boring, it’s usually because you haven’t injected any conflict into it.

TIP 7: If a scene has an adequate amount of conflict and is still boring, it’s usually because there’s nothing on the line (If you write a breakup scene where neither character cares whether they break up, we’re not going to care when they break up).

TIP 8: Unless voice over is organically infused into the story’s presentation (Fight Club), it’s almost always a lazy device.

TIP 9: If you haven’t combined at least two of your characters into a single character by your third draft, you’re not consolidating enough.

TIP 10: The less your hero speaks, the more active he needs to be (Drive, Mad Max). Nobody likes a quiet hero who doesn’t do anything (Mute).

TIP 11: The comic relief is not the guy trying to be funny. It’s the guy being himself who is inadvertently funny.

TIP 12: If you’re strong with concept and plot, gravitate towards features. If you’re strong with character, gravitate towards TV.

TIP 13: If a character is boring, start back at their introduction. You’ll almost always find that they have a flaccid boring intro. Give them a stronger intro and they instantly become a stronger character.

TIP 14: Due to the insane number of bad screenplays Hollywood has had to endure, everyone who reads your script will go into it assuming it’s bad. This is why it’s so important to yank them in right away with a great first scene.

TIP 15: A sudden twist (the hero’s boyfriend is the killer!) impacts the audience for five seconds. Dramatic irony (the audience knows the hero’s boyfriend is the killer but she does not) can impact the audience for half a screenplay.

TIP 16: At some point in the third act, your hero should face an impossibly hard choice.

TIP 17: If you wouldn’t watch what you’re writing, why would you expect anyone else to?

TIP 18: That’s you guys. Leave your best tip in the comments!

Yesterday’s celebration of the great country we live in led to thoughts of the not so nice things about the country we live in. I’m talking, of course, about Michael Bay movies. I remember July 4th of 2001 like it was yesterday. It was the day Michael Bay’s Pearl Harbor came out (it actually came out May 25 but just go with it for the sake of the article). The highly hyped film was suppose to be Bay’s version of Titanic. It was Titanic alright. A Titanic disaster. Actually, it was worse than a disaster. It was forgettable. The reason Bay’s movies are so forgettable is because he’s awful with character. He has zero understanding of what a character needs in order to emotionally resonate with audiences. Which makes sense when you consider he emerged from the world of commercials, where it was more about the product than the character selling the product. So to Mr. Bay and all other storytellers out there, today’s article is a cure for the Bad Character Blues. That’s right. Ten tips… to improve your characters right now!

Clear objectives – A character without a clear objective is an aimless wanderer. The audience becomes frustrated by that aimlessness and inevitably finds the character boring, or worse, annoying. The thing about objectives is that it’s so simple to incorporate them. In Jumanji, our characters’ objective is to return the jewel to its statue. Then they get to go home. How easy is that?

Unresolved relationships – Characters should have an unresolved issue with at least one other character in the movie. How compelling you make this issue plays an enormous part in how entertaining your script is. That’s because issues lead to conflict, and conflict is what you need to write good scenes between characters. Therefore, you want to get this right. In A Quiet Place, the dad has a broken relationship with his daughter, who’s become sick of all the rules they have to abide by as well as not allowing her to grow up. Take note of how simple that conflict is. I’m pointing that out because writers often think they need relationship conflict that’s really complex. No, it’s often simple universal things that every person experiences.

An inner battle – Give your main character something they’re battling internally. It could be a compulsion, like OCD, a vice, like meth, a fear or flaw, like standing up for themselves, or anything that involves an unresolved problem from within. This is one of the most important ingredients to breaking a character out of the 2-D mould and making them 3-D. A huge component of the human condition are the battles we fight within ourselves. Your characters should be no different.

Conflict with the past – Characters should have some unresolved conflict with their past. I call this the “fourth dimension,” as it takes your character from 3-D to 4-D. A character will have conflict with the external (1-D), other characters (2-D), the internal (3-D), and the past (4-D). It might be a traumatic event. It could be a death that wasn’t properly mourned. But it often has something to do with family. Every human being has a complex relationship with their family growing up, which is why it’s such a great place to look for this conflict. Good Will Hunting had to get past his abusive father in other to move forward.

A dash of good in the bad and a dash of bad in the good – A character who’s 100% good is boring. A character who’s 100% bad is boring. So you want to mix a little of each into the other. Denzel Washington in The Equalizer is a REALLY GOOD GUY. But he’s got a dark side. He’s a relentless killer, even enjoys it a little. It’s that edge that makes the character pop. Thanos is a REALLY BAD PURPLE GUY. But he’ll also sit down and talk to you in a calm logical manner. Those little splashes of good and bad are what keep a character from becoming cliche-bait.

Personality – This is one of the BIGGEST omissions I see in character-creation. Characters with zero personality. The writer then wonders why readers aren’t engaged. These are MOVIE CHARACTERS, guys. You thought them worthy of entertaining audiences for two hours. So give them some personality dammit! That doesn’t mean they have to be big and outlandish like Jim Carrey in The Mask. Personality can be dry humor, sarcasm, charm, attitude, arrogance. And every trait is scaleable. You can go big with humor or you can make it subtle, dependent on genre and tone. Thor was a dead MCU character until they gave him some personality.

Arc your character – Have your character start in one place and end in another. I don’t care how they change, but they need to change somehow. Or else the character becomes stale. In Paddington, the father starts off skeptical and resistant towards Paddington. By the end, he’s Paddington’s biggest supporter. Audiences love watching characters transform.

Give them a secret – In real life, we feel closer to people who share secrets with us. It’s a form of bonding. The same thing works with characters. If you know about their secret, you feel closer to them. Superman. Simon in Love, Simon. Jerry Lundegaard in Fargo – had his own wife kidnapped. If a character isn’t popping, try adding a secret and see if it helps.

Create contrast within the character – One of the biggest challenges in character creation is creating characters that feel fresh. A great way to overcome this challenge is to build contrast into character. So whoever the character is assumed to be, you balance that out with the opposite. A priest with an attitude. A comedian who’s a drag. An inappropriate HR rep. A bully with a lisp. A pacifist war vet. A cop who’s a drug addict.

Make sure something personal is on the line – I recently read a script where the hero succeeded at his goal, yet I felt nothing. I realized it was because there was nothing personal on the line for him. If this sounds like your script, let’s add some personal stakes to your hero’s journey! It could be a daughter who’s been kidnapped. It could be losing the love of your life. It could be saving a friendship. If you want to make it stick, make it personal.

One final note. You will never be able to use all of these tips on a single character. Every story is unique. Sometimes they require counterintuitive things from your characters. For example, Ferris Bueller needs to stay the same (violating tip #7) so that Cameron, his friend, can have the big powerful arc in the movie. With that said, you should be able to apply everything here to every script’s ENSEMBLE of characters. In other words, tip 5 may not work for your hero. But I’m sure you can add it to another character in the story. And with that, we’ve ended thin boring characters for all time. You’re welcome, Michael Bay.