Search Results for: 10 tips from

Two years in the making, the definitive book on writing dialogue is finally here. You can buy the e-book RIGHT NOW over on Amazon. Those of you who receive my newsletter already know this (if you want to sign up, e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com). The rest of you? What are you waiting for? It’s only $9.99, which gets you an unheard-of number of dialogue tips. A lot of these tips are things you can start applying immediately to improve your dialogue.

If you’ve already purchased a book, go write a review. Love it or hate it, it helps! I want to share all this knowledge I’ve accumulated with as many people as possible. So go get it!

One more announcement. This month is Tagline Showdown. Every month, I do a logline showdown. You send in your title, genre, and logline for your script. I post the best five loglines on the site. People on the site vote for their favorite. The winning logline gets a script review the following week.

This month we’re adding a twist! In addition to the usual information, you’re also going to send in your movie tagline. A movie tagline is the fun line they put on the poster. For example, The 40 Year Old Virgin tagline is, “The longer you wait, the harder it gets.” Army of Darkness: “Trapped in time. Surrounded by evil. Low on gas.” Memento: “Some memories are best forgotten.”

Start sending in those entries. Here are the details on how to submit!

What: Tagline Showdown

I need your: Title, Genre, Logline, and Movie Tagline

Competition Date: Friday, April 26th

Deadline: Thursday, April 25th, 10pm Pacific Time

Where: Send your submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

An excerpt from my upcoming book, “The Greatest Dialogue Book Ever Written”

There was a time when I didn’t think I was ever going to finish this book. There were too many technical obstacles (mainly regarding how ebooks interpret screenplay-formatted text) that required endless troubleshooting. But I’m SOOO excited that I’m finally about to release the book because I truly believe it will be the seminal book on dialogue for the next 50+ years.

It’s a book with 250 dialogue tips. This in an industry where you’re lucky to find someone who can give you 10 dialogue tips. And I just can’t contain how thrilled I am that I can finally share it with you. I already posted the opening of the book the other week. In today’s post, I’m including a segment from the “Conflict” chapter. This is arguably the most important chapter in the book and it contains 21 tips total.

TIP 121 – Make sure there’s conflict built into the relationship of the two characters who are around each other the most in your movie/show – Who are the two characters who will be around each other the most in your script? You need to build conflict into the DNA of that relationship specifically. That way, almost every scene in your movie is guaranteed to have conflict. John and Jane in Mr. and Mrs. Smith, Tony Stark and Steve Rogers in Civil War, Allie and Noah in The Notebook, Lee and Carter in Rush Hour, Danny and Amy in the Netflix show, “Beef.”

TIP 122 – Using worldviews to create conflict – Okay, but how do you build conflict into the DNA of a relationship? One way is to give characters different worldviews. Have them see the world differently. If you do this, your characters will be at odds with each other for an entire movie as opposed to one or two scenes. In the Avengers movies, Tony Stark’s worldview is he’s willing to get dirty to protect the universe. Steve Rogers’ worldview is governed by honesty. He wants to play by the rules. That difference in their worldviews is why the two butt heads so much.

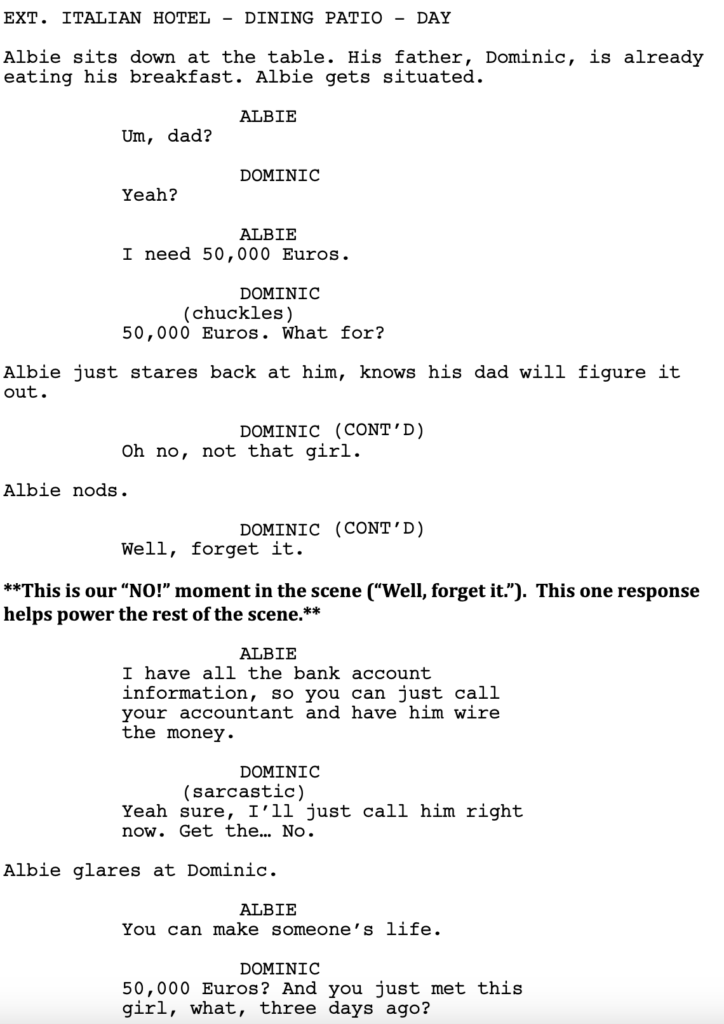

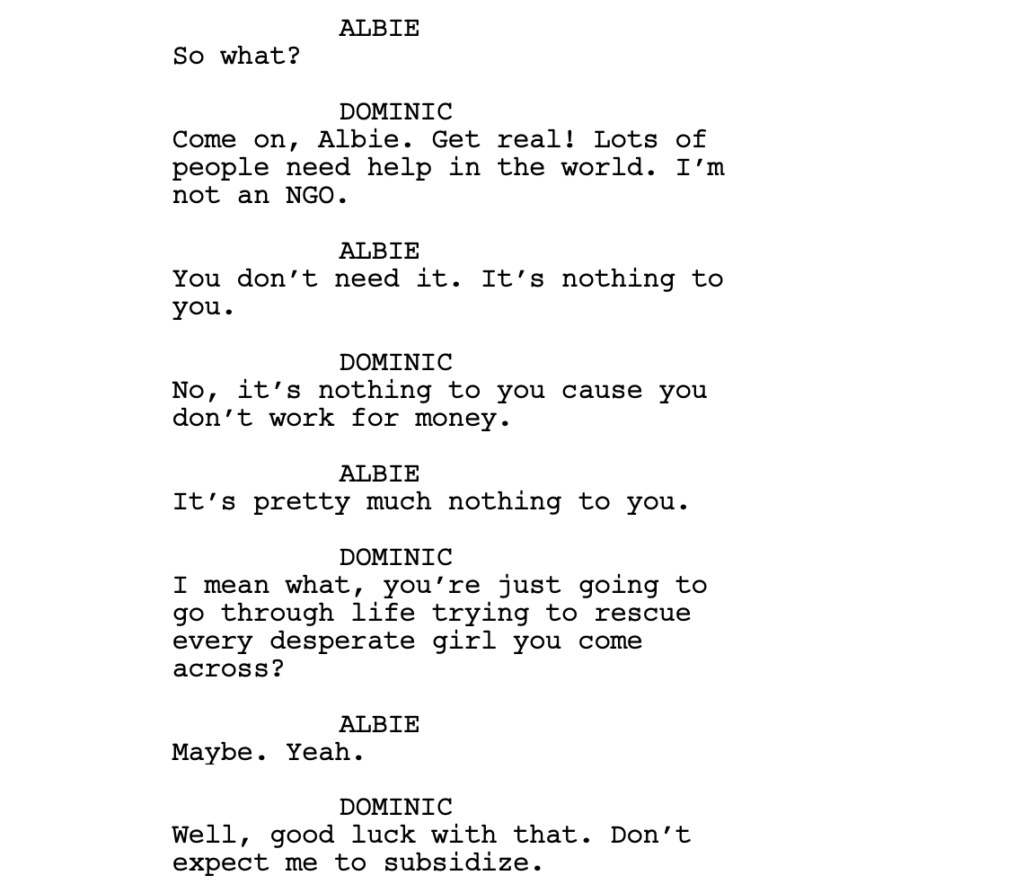

TIP 123 – Embrace the word “NO” – “No” is the OG conflict word. Without it, most conversations become boring. Let’s say your hero tells his wife, “I’m going to the store,” and she replies, “Okay.” How is that going to result in an interesting conversation? Or your assassin asks his handler, “Is it okay if I skip this assassination? I don’t think it’s safe enough.” And the handler replies, “Sure, no problem.” When people agree with people, the conversation immediately stops. This is why you want to integrate “No” (and all forms of it) into your dialogue. Here’s an example from the HBO show, White Lotus. In it, 23 year old Albie has fallen in love with a local Italian prostitute who owes her pimp money. Albie wants to help pay her pimp off, so he comes to his rich father to ask for money.

TIP 124 – Make them work for their meal – The reason “No” is so great for dialogue is that it forces your character to work for their meal. They don’t get a free pass. The above scene goes on for another three minutes and Albie has to resort to offering something to his father to get the money. That’s what makes the scene entertaining – that he has to work so hard for his meal. And he wouldn’t have had to do it if his dad had said, “Yes.”

The Scriptshadow Dialogue Book will be out within the next two weeks. But there’s a chance it could be out A LOT SOONER. So keep checking the site every day! In the meantime, I do feature script consultations, pilot script consultations, short story consultations, logline consultations. If you’ve written something, I can help you make it better, whether your issues involve dialogue or anything else. Mention this post and I will give you 100 dollars off a feature or pilot set of notes! Carsonreeves1@gmail.com

An excerpt from my upcoming book, “Scriptshadow’s 250 Dialogue Tips”

It has been promised. But as of yet, it hasn’t been delivered.

Over the next month, I’ll be including excerpts from my upcoming dialogue book, which I’m planning on releasing a month from now. Here is the introduction to the book. The world of screenwriting is about to change forever.

What you’re about to read is the introduction to the book…

Not long after I started my website, Scriptshadow, a site dedicated to analyzing amateur and professional screenplays, I was hired by an amateur writer to consult on a script he had written. The writer had completed a couple of screenplays already and was excited about his most recent effort, a crime-drama (“with a hint of comedy”) he felt was the perfect showcase for his evolving skills. Although I won’t reveal the actual script for privacy reasons, we’ll refer to this screenplay as, “Highs and Lows,” and we’ll call the writer, “Gabe.”

Highs and Lows was about a guy obsessed with a rare street drug and, to this day, it is one of the worst screenplays I have ever read in my life. We’re talking 147 pages of unintelligible nonsense, a script so aggressively lousy, I considered submitting it to the CIA as a low-budget alternative to waterboarding.

After I put together the notes on Highs and Lows, I spent a good portion of the day debating whether I should call Gabe and aggressively suggest he pursue a different career path. I’d never done such a thing before. But, in my heart, I knew that if this man pursued this craft, he may very well end up wasting a decade of his life. If it wasn’t for my girlfriend ripping the phone out of my hand and telling me there was no way I was going to destroy this writer’s dreams, I would’ve made the call. Instead, I sent him his notes, detailing, as best I could, what needed to be improved and how to do so, and moved on.

Cut to five years later and I was contacted by a different gentleman (we’ll call him “Randy”) for another consultation. In stark contrast to Gabe’s script, I experienced what every reader prays for when they open a screenplay, which is a great easy-to-read story with awesome characters. But it was the dialogue that stood out. Randy wasn’t ready to challenge Tarantino just yet but the conversations between his characters were always clever, always engaging, and always fun.

I sent his script out to a few producers and one of them ended up hiring him for a job. He wrote back, thanked me, and mused that he’d come a long way since our first consultation. “First consultation?” I said to myself. “What is this guy talking about?” I looked back through my e-mails to see if we had corresponded before and nothing came up. But then I dug deeper and discovered that I *had* worked with Randy before. Under a different e-mail address.

The owner of that e-mail?

Gabe. Which was a pen name he had used at the time.

This was not possible. Randy wrote with confidence. Gabe wrote like he’d accidentally fallen asleep on his keyboard. I went back and re-checked, checked again, checked some more, only to return to the same baffling conclusion. This page-turning Tour de Force was written by the same writer who had written one of the worst screenplays I’d ever read!

After my denial wore off, I got in touch with Gabe and asked him the question that had been eating at me ever since I confirmed his identity: “What in the world did you do differently this time around?” I especially wanted to know how his dialogue had skyrocketed from a 1 out of 10 to an 8 out of 10. His answer is something I’ll share with you later in the book, as it’s one of the most important tips you’ll ever learn about dialogue.

But for now, I want to emphasize the lesson Gabe’s dramatic improvement taught me, something I remind myself whenever I read a not-so-good screenplay: You are always capable of improving as a screenwriter. If Gabe could go from worst to first, so can you.

Which is why I want to share with you one of the biggest lies you’ll encounter when you begin your screenwriting journey. I heard it a bunch when I first started screenwriting and I still hear it today: “You either have an ear for dialogue or you don’t.” This faulty statement, which you’ll hear mostly from snobby agents, jaded executives, and impatient producers, is dead wrong.

Writing good dialogue can be learned.

Let me repeat that:

Writing good dialogue can be learned.

To be fair, doing so is challenging. More so than any other aspect of the craft. Aaron Sorkin, who many believe to be the best dialogue writer working today, admits as much. In an interview with Jeff Goldsmith promoting his film, The Social Network, Sorkin confessed that while storytelling and plotting are built on a technical foundation, making them easy to teach, writing dialogue is more of an instinctual thing, and therefore hard to break down into teachable steps.

Indeed, dialogue contains elements of spontaneity, cleverness, charm, gravitas, intelligence, purpose, playfulness, personality, and, of course, a sense of humor. This varied concoction of ingredients does not come in the form of an official recipe, leaving writers unable to identify how much of each is required to write “the perfect dialogue.” Which has led many screenwriting teachers to throw up their hands in surrender and label dialogue, “unteachable,” which is why there hasn’t been a single good dialogue book ever written.

When screenwriting teachers do broach the topic of dialogue, they teach the version of it that’s easiest on them, which amounts to telling you all the things you’re NOT supposed to do. My favorite of these is: “Show don’t tell.” Show us that Joey is a ladies’ man. Don’t have him tell us that he’s a ladies’ man.

“Show don’t tell” is actually good screenwriting advice but why do you think screenwriting teachers are so eager to teach it? Because it means they don’t have to teach dialogue! If you’re showing something, you’re not writing any conversations.

Or they’ll say, “Avoid on-the-nose dialogue.” Again, not bad advice. But how does that help you write the dialogue that stumbles out of the mouth of Jack Sparrow? Or sashays out of the mouth of Mia Wallace? In order to write good dialogue, you need to teach people what *to* do, not what *not to* do.

If you ever want to test whether a self-professed screenwriting teacher understands dialogue, ask them what their best dialogue tip is. If they say, “go to a coffee shop and listen to how people talk,” run as far away from that teacher as possible because I can promise you they know nothing about dialogue. If someone is giving you a tip where there’s nothing within the tip itself that teaches you anything, they’re a charlatan.

What the heck is good dialogue anyway?

Good dialogue is conversation that moves the scene, and by association the plot, forward in an entertaining fashion. “Entertaining” can be defined in a number of ways. It could mean the dialogue is humorous, clever, tension-filled, suspenseful, thought-provoking, dramatic, or a number of other things. But it does need those two primary ingredients.

• It needs to push the scene forward in a purposeful way.

• It needs to entertain.

What prevents writers from writing good dialogue? That answer could be a book unto itself but in my experience, having read over 10,000 screenplays, the primary mistake I’ve found that writers make is they think too logically.

When they have characters speak to one another, they construct those characters’ responses in a way that keeps the train moving and nothing more. They get that first part right – the “move the story forward” part – but they forget about the “entertain” part. Don’t worry, I’ve got over a hundred tips in this book that will help you write more entertaining dialogue.

Yet another aspect missing from a lot of the dialogue I read is naturalism – the ability to capture what people really sound like when they speak to each other. You are trying to capture things like awkwardness, tangents, authenticity, words not coming out quite right. You’re trying to mimic all that to such a degree that the characters sound like living breathing people.

And yet, while being true-to-life, you’re also attempting to heighten your dialogue. You’re trying to make every reply clever. You’re trying to nail that zinger. You’re giving your hero the perfect line at the perfect moment. How does one combine realism with “heightened-ism?” That’s one of the many paradoxes of dialogue.

So I understand, intellectually, why so many teachers are terrified of dialogue. The act of writing movie conversation is so intricate and nuanced that the easy thing to do is leave it up to chance and tell writers that they either have an ear for it or they don’t (or to go to a local coffee shop and “listen to people talk”).

But dialogue is like any skill. It can be learned. It can be improved. And I dedicated years of my life looking through millions of lines of dialogue, ranging from the worst to the best, to find that code. And I believe I’ve found it. By the end of this book, you’ll have found it as well.

It won’t be easy. This is stuff you’ll have to practice to get good at. But, once you do, your dialogue will be better than any aspiring writer who hasn’t read this book. That much I can promise you.

So let’s not waste any more time. I’m going to give you 250 dialogue tips and I’m going to start with the two biggest of those tips right off the bat. If all you ever do for your screenwriting is incorporate these two tips, your dialogue will be, at the very least, solid. Are you ready? Here we go.

TIP 1 – Create dialogue-friendly characters – Dialogue-friendly characters are characters who generally talk a lot. They are naturally funny or tend to say interesting things, are quirky or strange or offbeat or manic or see the world differently than the average human being. The Joker in The Dark Knight is a dialogue-friendly character. Saul Goodman in Breaking Bad is a dialogue-friendly character. Deadpool is. Juno is. It’s hard to write good dialogue without characters who like to talk.

TIP 2 – Create dialogue-rich scenarios – Dialogue is like a plant. It needs sunshine to grow. If every one of your scenes is kept in the shade, good luck sprouting great dialogue. A scene where a young woman introduces her boyfriend to her accepting parents is never going to yield good dialogue. There’s zero conflict and, therefore, little chance for an interesting conversation. A scene where a young woman introduces her boyfriend to her highly judgmental parents who think their daughter is too good for him? Now you’ve got a dialogue-rich scenario!

I need you to internalize the above two tips because they will be responsible for the bulk of your dialogue success. Try to have at least one dialogue-friendly character in a key role (two or three is even better). Then, whenever you write a scene, ask yourself if you’re creating a scene where good dialogue can grow.

Don’t worry if these two things are confusing right now. We’re going to get into a lot more detail about how to find these dialogue-friendly characters and how to create these dialogue-rich scenarios.

A pattern you’ll notice throughout this book is that good dialogue comes from good preparation. The decisions you make before you write your dialogue are often going to be just as influential as the ones you make while writing your dialogue.

There’s more to come next week! If you want to hire me to take a look at your script and help you with your dialogue (or anything else), I will give you $100 off a set of feature or pilot notes. Just mention this post. You can e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com

The Scriptshadow March Newsletter is in your Inboxes! You can discuss the newsletter on the official post here!

A couple of weeks ago I sat down with screenwriter (and actor, and director) Leah McKendrick on a rainy LA morning at my favorite coffee spot, Sightglass Coffee, just off of LaBrea. It’s this big open space with a lot of creatives working there and I always enjoy the energy. If anyone wants to come by and say hi, I’m there three times a week. I’m usually working on an ipad with a white keyboard.

I wanted to catch up with Leah because she’s got a new romantic comedy called Scrambled, about a woman in her 30s who, because she doesn’t have a partner, has decided to freeze her eggs. It turns out to be an emotionally frustrating experience balanced out by a lot of humor, brought on by characters who seem utterly flummoxed by this choice of hers.

Our conversation was long and winding and while I originally planned on editing it down, I ultimately decided to keep it all because there’s some really great stuff here. Stuff about agents, dialogue, struggle, how to stay motivated, how to take your career into your own hands. I’m a huge fan of how Leah makes things happen in an industry that doesn’t want anything to happen. I’m going to pick things up BEFORE we started talking Scrambled. While waiting for Leah’s croissant (“I just got off the actress diet so I need carbs before we start.” “What’s the actress diet?” “When you don’t eat anything.”), Leah mentioned that she had developed a show at HBO before it fell through. So I asked her what it was like working with HBO…

LM: Yeah, I don’t know how it compares to other networks. I will say, all of the notes that I received were really smart. And really fair.

CR: Who was giving you notes from HBO? They assign you to a specific person there?

LH: Yes. Exactly. And that person’s team. But you have a point person you talk to. And that’s what’s really hard I think about making studio shows or studio films. There’s always another “box” higher up. Until it reaches the top. You’re never working with “the top.” So even if your point person absolutely loves what you guys are creating together, it still needs to work its way up the ladder. And if that top person changes for one of these 8 million reasons that top-people-changes happen, your project’s done. Because they don’t have any deep connections with your project. They weren’t a part of moulding it.

So that’s been something that’s been really hard for me is that I can be working with the studio very closely and they could be loving it and we could be really vibing but if their boss or their boss’s boss doesn’t get it? Like, “We gave it our best shot!” But I don’t view it that way. I view it like, “This is my blood sweat and tears. This is my baby.” But that’s just how this business works. Unless you’re getting to work with Nathan Kahane himself at Lionsgate. Like, it’s still got to make its way to Nathan and he’s still got to sign off on it. Thank god on Scrambled (laughs) Nathan signed off on it. There’s a good chance that Nathan could’ve been like, “No,” and Scrambled wouldn’t have been a Lionsgate movie. It still would’ve been made. But it wouldn’t have been a Lionsgate movie.

CR: So let’s talk about Scrambled because it feels like it’s the best example ever of “Write what you know.” Is that how this script came about? You thought, “I’m going through this. I need to write a script about it.”

LM: Yes. I was pissed off that I had to spend 14 grand (on freezing my eggs). So I was like, “I’ll use it as research and I’ll write a movie about it.” And I don’t even know how strong that urge was because more than anything I was like “I just have to get through this and freeze my eggs.” And I thought I wouldn’t write during that time because the pandemic was going on and that complicated things. But then out of curiosity, I started googling fertility films. And I realized there was no film about egg-freezing. It was always about the other methods. But those methods were about getting pregnant. And I was trying to do the opposite. I was trying *not* to get pregnant. Cause I didn’t have a guy. I was trying to buy more time. And that’s just so isolating and alienating for women. So I started writing down notes. And I just didn’t feel creative in that moment at all. And then as soon as I was done with my egg-freezing it was back to work. I had deadlines on other movies so I didn’t do anything with it until a year later after they killed Summer Loving (a Grease prequel Leah was working on) and they killed my directorial debut (another movie) and I was like, “I am not doing this anymore.” So I was like “I’m going to write my… give me three weeks, I will write my film about egg-freezing.”

CR: Is this something you ever discuss with your agent and management teams?

LM: (laughs) No. My team is the best. They know that I always go rogue.

CR: So then you guys never sit down together and they lay out a career game plan, such as, “Here’s what we think you should write? These types of movies are doing well so maybe you write one of them. This trend over here is hot so maybe write that?”

LM: Good question (thinks about it). No. In the beginning of my career they did. They tried to get me to chase moving targets. Nowadays no. And I would really advise writers away from that. “Knives Out did well so now go write a murder mystery.” Unless you LOVE murder mysteries, dope, go write it. But I know what I have, which is a pretty limited toolbox of things that I’m good at. So that’s what I write.

CR: You know your lane.

LM: Mm-hmm. I know my handful of lanes, I should say.

CR: Are you in the left lane or the right lane?

LM: Both at once, at all times.

Carson and Leah crack up.

LM: I’m in all the lanes at once which is what I should really say. But no, nowadays my team doesn’t try to get me to write in a genre or a specific type of film. They will say to me, “This project which you mentioned a year ago. What if we brought that one back?” Or, “You’re getting offered a lot of these types of genres. Do you want to do one of them?”

CR: So they’re coming to you with offers?

LM: Mm-hmm.

CR: And you consider that because it’s a paying job.

LM: Very rarely but at one point I did.

CR: Now, not so much?

LM: No, now (facetiously) I’m drunk with power. (Laughs). Now I don’t want to do anything that anybody wants me to do. Now I just want to build my own shit from the ground up and die on that hill. After they killed my TV show and they killed my two films, I just felt like I had done everything right. I’d played by the rules. I had been a good little soldier. And for what? You just killed everything.

CR: That seems to have had a big effect on you.

LM: A BIG effect on me. People feel like I should feel so much triumph because I made Scrambled and I do. But I’m so heartbroken. I will always be heartbroken because I worked so hard… here’s what I’m trying to explain because it’s not just my creativity. Because us artists have unlimited creativity. The more we sew, the more we reap. The more we create, the more we will create, the more that comes to us. BUT. That’s YEARS of my life. That’s what isn’t limitless. Is the days and the months and the years that I invested in building what they told me to. And then they didn’t even make it. So why would I continue to invest my one precious life into what you’re telling me to make if you’re not actually going to make it? So I was like, “The only way I have seen a way that has PROVEN ITSELF to be worthwhile and that has actually led to movies is when I was the one behind it. And I was the one who was saying this is when we’re shooting and this is how we’re going to get the money.

CR: So you wrote, starred, and directed in this movie.

LM: Yes.

CR: How did you do that? That’s hard.

LM: It was hard. But like I said, I was clean out of f$&%s. I was like, I’m not handing over my script. I’m not selling my script. Why would I go into development for three years? Regime change. More development. And another regime change. You kill it five years later. I don’t even own it anymore. It was an inefficient system that I could not subscribe to.

CR: One of the things that amateur screenwriters struggle with is a little bit of what you’re talking about but they feel even less power. They work on something and they don’t even know if an agent is going to pay them any attention. So that’s why a lot of them give up. They go through that process four times. Each time takes a year out of their life. They get rejected each time. And they finally say, “What’s the point?” But you seem immune to that. You continue to be more motivated than anyone I know.

LM: Yes.

CR: Where does that come from and how do you generate it?

LM: We’re going to get really deep for a second because it’s a sad answer. But that comes from the fact that my whole life I’ve felt behind. I have felt like I have failed. And it’s because I thought I was going to be Britney Spears at 16 years old. I was so frustrated as a kid. I had no interest in playing. I wanted to work. I don’t know where that comes from because my parents were not like, “You need to work.” But when you have had huge dreams your whole life and nothing has happened on the timeline that you wanted it to, it makes you quite desperate. It makes you feel like no one is getting it.

CR: I didn’t know you did singing.

LM: Oh yeah. I would make my own costumes and hire dancers with my allowance money when I was in high school.

CR: See, THAT. Right there. You went further than the average person would go. And this was technically before you were “behind” in life, right?

LM: Even then I felt behind. I wanted to be a Disney kid. I wanted to be Miley Cyrus and be on a Disney show. My parents were not into that. I was resentful. Cause I read about all these other kids whose parents would move with them to Hollywood and when I brought that up to my parents, they looked at me like… “We don’t even know what you’re talking about.”

Carson laughs.

CR: Let’s talk about Hollywood for a second and the pursuit of one’s dreams. Because there seems to be two ways to approach it. The first way is a negative one. You put your stuff out there and you think, “It’s probably going to be a no.” And the other way is positive. You put your stuff out there and, in spite of the no’s, you continue staying optimistic. You keep going. How do you keep that optimism having been through these numerous failures? How do you keep pushing no matter what?

LM: I think the thing that fed me and gave me that stamina all those years was that blind optimism of “I’m meant to be what I dream of becoming.“ Therefore, if I just reach the right people, they will see that I’m meant to do this and when that was proven wrong, it was a huge destruction of a worldview for me. Since then, what I think has happened, and this is a way I’ve evolved, and this is kind of sad also to be honest. Is that I’m not…….. good enough to be up there so I will have to make up for that in hard work. And that is why I decided that I had to write, and direct, and produce, and star, and finance (laughs). I will have to do EVERYTHING in order to make movies. I don’t believe anymore that I will reach the mountaintop. That I will reach the emperor and that he or she will tell me that I “made it.”

CR: (laughs) That moment never comes for anybody.

LM: (laughs) Exactly.

CR: Okay, so what I want to talk about is dialogue. You know I’m a fan of your dialogue. We talked about dialogue last time. This movie is very dialogue-driven. Have you learned anything new on the dialogue front since we last talked?

LM: Funny thing. Since we set up this interview, I’ve been waking up in a cold sweat in anticipation of this question. Cause I felt like last time I wasn’t prepared for it and I didn’t give a very good answer. That’s because a lot of it is instinctual to me.

CR: Yeah, that seems to be a common response from writers who are good at dialogue. They don’t have the best dialogue tips because they don’t have to think about it.

LM: Yeah.

CR: Well I have good news for you. I have it on good authority that if you give me a good answer, the Hollywood god will finally tell you you’ve made it.

LM: (laughs) I have one bit of advice I can give…

Quick Context Break: Both myself and Leah are big fans of the reality show 90 Day Fiancé. I have spared you from our conversation about the show in this interview. Don’t judge. Ryan Gosling is also a fan. Earlier, we were discussing one of the couples on the show. Their names are Geno and Jasmine. In the most recent episode, they got married. This is the context for Leah’s answer.

LM: On 90 Day Fiancé Geno and Jasmine were getting married and they were exchanging vows. So Geno’s giving his speech. His vows are what I would call “platitudinous.” They were enough for Jasmine and I love that. He’s not a writer by any means. And it was from the heart. But I forgot everything he said the minute he said it. Because everything that he said has been said a million times before. And I think that I am more interested in characters saying the wrong thing, or the semi-wrong thing, or going in a weird direction where you’re like, “ooh, this feels a little cringe.” And then coming around at the end and having one line that is so heartfelt. At least I will remember that moment and I will remember that writer who wrote that moment. Because if you’re going to sit up there and your vows are, “You complete me” and “I wasn’t myself until I met you” and “I’m going to love you forever.” No one remembers any of that.

So my boyfriend’s aunt was telling me a moment in my movie that really spoke to her and it’s this moment where a character is talking about their lost pregnancy. A miscarriage. And they had written a letter to their lost child. And they’re listing all these things that they wish they could’ve done together and one of them was, “I had all these plans to teach you how to not pluck your eyebrows, how to drive, and how to cook a chicken.” And she said the part about cooking a chicken just got her. And it’s like, “Why? Why is that?” Cause I don’t always know when I’m writing what’s going to hit, what is going to resonate. She said she couldn’t even explain what it was. Then we talked about it for a minute. And my thing was, as a Nicaraguan woman (my mom is from Nicaragua), it’s a big right of passage to pass on these skills. And one of those is roasting/cooking a chicken. And so I was just thinking about it in those terms. You know, when your kid graduates from high school and you’re sending them off to college, there are some skills that you want them to have. Right? You want them to know how to fold a fitted sheet. You want them to know how to cook at least something. Can you scramble an egg? So I was trying to come up with these basic go-tos of parenting. But the chicken really struck her, I think, because it’s visual. Because it’s specific. I think because it’s a rite of passage that only a mother would really know.

My larger point about dialogue is, the more general you get, the more forgettable it is. And the more specific you get, even if it’s the wrong thing, the more memorable it will be. And I would advise writers to use their own lives…. Like if you were going to teach your kid five things, what would those five things be? Get really specific. Because I promise you they wouldn’t be, “Oh, how to love.” (Laughs) You know? I don’t think that us as humans if we’re really in it or really honest, the more general it is, it means you’re not really trying. You’re not really thinking about it. It doesn’t matter how sweet your vows are. If they’re too general, they are in one ear and out the other.

CR: I like that answer because I deal with platitudes a lot and it’s a problem. More so in loglines lately. Wait, do you still have to write loglines as a working writer?

LM: I still write loglines. Yeah.

CR: Yeah, a big problem in the logline universe is general phrases that mean nothing. And for some reason, it’s hard for writers to understand that when I tell them not to do it. I don’t know why that is.

LM: You know what I think it is? And I mean no disrespect because I did it too. Sometimes we are *performing screenwriting.*

CR: What do you mean by that?

LM: You’ve seen so many movies your whole life. You’re like, “Oh, that’s what a movie is. That’s what movie dialogue is.” Which leads to imitation movie dialogue. As opposed to “I’m not imitating movies. I’m imitating real life.” And also, in some ways NOT imitating real life. Because real life can be quite boring. And like Geno saying his vows, real life vows are not always great. For some reason, I keep thinking of Jerry Maguire. That speech, “You complete me.” Yes you can say that that “hits” because… Tom Cruise. But I actually think it hits because he has not been that person for the entire film. The entire film he’s so self-involved. It’s all about him. It’s all about, “Who’s coming with me to help me because of who I’m supposed to be.”

CR: Jerry Maguire sounds like 16 year old you.

LM: (laughs) True. Yeah, he’s like who’s going to help me start my business, I’ve got to write this manifesto, I gotta get clients. Dorothy’s just on the sidelines. And there’s this big reversal in this final moment where he realizes I’m nothing without you. And they were able to encapsulate that moment through dialogue.

CR: Would you have written that line?

LM: (spends the longest time thinking about the question of any moment in the interview) I think… I think I would’ve written something along those lines. I don’t know if it would’ve been fucking epic.

Carson laughs.

LH: But I can feel in my heart as a screenwriter that that’s his journey. That his journey informed the line. And that’s why I get frustrated sometimes by studio notes is that, sometimes we’re so afraid of characters not being likable, that their arcs are (Leah visually mimics a flat line path with her hand) Wah-wahhh. And I’m like, “People will want to be on a ride and if somebody is… if you’re struggling to like them… that’s okay. As long as you give them that moment in the end. But I’m personally more comfortable having somebody be a little more self-involved, a little bit of a dick, a little selfish.

CR: What is your character in Scrambled like? Is she unlikable? What’s her flaw?

LM: No, I think people really like her. The flaw is, I would say, that there’s some arrested development there. She’s struggling to grow up.

CR: Now, you’re basing her on yourself, right? So you have to do some pretty intense self-reflection to write that.

LM: I mean, I think I’m still struggling to quote-unquote “grow up.” But I would point a finger at society telling me that growing up is being a mom. And I’m going, I don’t think that’s true. I think I’ve grown up in a lot of ways. And I am an adult in a lot of ways even though I don’t have a picket fence and a husband and 2.5 kids and an “acceptable” job. So yes, in some ways it’s her reckoning with society’s standards of what an adult woman should look like. But also the ways in which she herself has been infantilizing herself is a rebellion against that. And I think that’s totally me. I have a hard time with a lot of this stuff. I feel like I have worked my ass off and I have a career in the toughest industry in the world. Why isn’t that recognized as “adult?” Why isn’t that recognized as a huge triumph for me?

CR: Sounds pretty good to me.

LM: Well thank you. But you get it. Because you’re here. People who aren’t… have always been so curious about my love life. Always so worried about my age.

CR: What is that like for you? When you get that question? And are these moments in the movie?

LM: The whole movie is moments like that. I will tell you in one instance…I had just been hired for a big screenwriting job. I was very excited. It was early on in my writing career where I wasn’t getting offered big jobs and I had fought for this one. And I was telling a friend. I was so excited. I was feeling really good. And her question was, “Aren’t you worried about having kids cause you don’t have a boyfriend?” It felt so out of left field. And it kind of kept me up at night.

CR: What did that have to do with you getting the job?

LM: Excellent question. I think she may have been projecting some of her own fears on me. She was seeing me successful and wondering why she hadn’t been able to figure out that side of life yet. But I confronted her about it later and we worked it out.

CR: Is that in the movie?

LM: Not specifically but the whole movie is this specific conflict. How you shouldn’t measure a woman’s life achievements by these metrics. Husband. Baby. House. And when I did buy my house, it did feel like this moment where I was like, “Well I don’t have a husband. But I bought my house from this money that I made from my dreams. Every dollar that bought this house was from my acting and my writing. So fuck you. Cause I still got here. And I still have a house in the exact area that I wanted to get a house (in the Hollywood Hills) and it may just be alone but I’m not behind. And that was what was really hurtful. That everybody made me feel that I’d chosen my career over having a family and I had ruined my life because I had chosen my career. That’s what the film’s about.

CR: Random question. Was buying that house stressful?

LM: Super stressful.

CR: Could be a future screenplay. The struggles of buying a house.

LM: (laughs) It’s funny because when you start making money you become a bit existential about it. “What is this money I’m getting? What does it even mean?” But when you buy that house and you’re sitting in your chair looking out your window in the exact type of home you’ve always wanted in the exact area that you’ve always wanted, that’s when you realize what the money is for. That piece of mind and that safety. There’e something tangible I can point at. I had nothing when I moved here. My parents had cut me off because they said, “You have to do this on your own.” And now I have a house in the hills. And I achieved that by doing all the things that people told me not to do. So that’s my little arc.

CR: So when can we see Scrambled!

LM: It’s coming out March 1st on streaming! Apple, Amazon, and On Demand services. Oh and by the way, I just wanted to give a shout out to your site because last time I did an interview I was terrified to check the comments because I never check the comments cause they’re always mean. But the people on your site are so positive and supportive. It was really cool.

CR: Yeah, outside of a few outliers in the comments section, 99% of the people are very positive in their discussion about screenwriting.

LM: Oh, I wanted to say one more thing before we stop. We were talking earlier about screenwriters giving up. And whenever I hear that, it hurts my soul. Cause think of all the incredible scripts and stories that will never be written or made because of that. And regarding what I’m about to say, if this is not you and this is not in your heart, that’s fine, I understand that. But if you have this amazing story and nobody’s giving you the time of day, consider putting on that producer hat. Stop thinking that others passing on your screenplay is where it ends. I don’t care if you’ve written Citizen Kane. It doesn’t go anywhere without you. I’m of the Duplass brothers school of making movies. Which is, “How inexpensive can you make it?” “Is there a version you can do for 100 grand, 200 grand?” I know we would all love 5 million dollars to make our first movie. I know! But they’re not handing that shit out. I’m such a big believer that if you want to be making movies you have to be making movies.

So many people in this town don’t want to read your script. Like people send me their script and want me to read it – I DON’T EVEN READ. I’m trying to change that but we’re all busy, you know? It’s so hard to get people to read your script. But they *will* watch your movie. Making something small. Even if it’s a dope ass scene. Or even if it’s a teaser. I just feel like the thing that has done more for me in my career than anything else is making my own work. Taking my scripts and getting friends, raising a little bit of money, going to the festivals trying to turn it into something bigger, that has been my trajectory. And I know that it can be disguised by the fact that I’ve been writing studio films. And look, I’m grateful that I have a house like I talked about. But that didn’t get me Scrambled. The way that I got Scrambled is by saying I’m *not* doing that anymore. I am going to make this. I’m going to direct it. I’m going to star in it. I’m not taking no for an answer. And they try to dissuade you. A lot of companies offered me money if I wouldn’t act. Or I wouldn’t direct. They always do that. And it makes you feel sh&%$y. But my point is I wish that screenwriters also saw themselves as filmmakers, also saw themselves as producers. Because that will make all the difference in your life.

CR: Do you think you would be successful if you only wrote scripts to sell them?

LH: 100% no. 100,000% absolutely not. I think there are better writers who have smaller careers than me. The way that I got a screenwriting career was by making MFA (her first film about a campus rape). And I’ll be honest. I reread that script not that long ago and I was like, (laughs) “This is not good.” I thought it was the best shit ever when I wrote it. I thought I was Aaron Sorkin. I really did. But at the time it was the best that I could do. Truly. The beauty of it: it was a decent script, it was a better film. Because my director and main actress knocked it out of the park. And then it went to South by Southwest because South-by just f&%$ing gets it. And they can see… ideas. Even if they’re not fully formed. And it came out the week of the Weinstein scandal and the birth of #metoo. So there was some luck there.

But that happened and I had a screenwriting career. And then I was selling scripts right and left. And then I was getting called for adaptations. That would not have happened with the script alone. I’m telling you. The script was not that good. But the beauty of it is that I took my script and held it tight and I was like, “I’m muscling my way to the finish, eyes closed with or without any of you people.”

So I would just say, writers, I promise you, probably 90-95% of you are more talented than I am (laughs). But I’m very very very tenacious. And hard-working. And my secret to producing is just, I’m good at asking for things that I have no business asking for. I’m good at calling up everyone I know and going, “Have you ever thought of investing in film? Have you ever wanted to be in a movie? Can I use your house to shoot in? Can I use the campus to shoot in?” I’m good at that. I’m good at calling up SAG and saying, “This isn’t fair. You gotta let me star in my own film and not be creating all this red tape for me to rehearse. I’m good at calling everyone up and being like, “I need to get this done.” And the smaller the project, the more miracles will happen. That’s how it is. The bigger the project, the more bullshit will happen (laughs). The smaller and scrappier your film is, the more times you’ll have someone say, “Eh, all right, you can shoot in my backyard. All right, you can have free parking.” You know, I put every penny I had ever saved up in my life at the time into that film? 10,000 dollars. It was my hail mary. I didn’t have a plan B.

CR: Leah, you are the Katt Williams to my Shannon Sharpe. You held nothing back today. Thank you for coming out on this uncharacteristically rainy LA morning. Any last words?

LH: Go watch Scrambled!

The most clever horror premise I’ve read all year. It Follows meets The Ring!

Genre: Horror

Premise: A young woman finds out, after breaking up with her boyfriend, that everyone who breaks up with him dies exactly three days later.

About: The short story sales continue! In addition to “It’s Over,” we also have the new Ridley Scott short story project, “Bomb.” I’m trying to get my hands on that one as well so maybe I’ll be reviewing it soon. “It’s Over” sold for mid-six figures to Sony and will be adapted by Akela Cooper, who scripted, “M3GAN.”

Writer: Jack Follman

Details: 28 pages

Prey’s Amber Midthunder for Jen?

Prey’s Amber Midthunder for Jen?

Short stories taking over Hollywood. Who would’ve thought?

I wonder if the reason these things are selling is because Hollywood realized they were going to rewrite any spec sales anyway. So why not substitute in a piece of writing that allows them to craft the script from conception? There is no script with a short story so you can build the building however you want, as opposed to having to redesign it, which can be deceivingly difficult.

Jen has been with Lucas for five years. The two began dating in college and Jen is finally realizing that they were in a relationship of convenience. She doesn’t love him anymore. Therefore, it’s time to break up. So she meets with him, tells him it’s over, and gets the shock of her life.

Lucas says she can’t break up with him. “Why?” She asks. “Cause you’ll die. Every girl who has ever broken up with me dies exactly 3 days later.” Jen is weirded out, and after arguing with Lucas about this insane statement, she heads over to her best friend, Maggie’s, house for some girl support.

She’s shocked to find Maggie wasted, and after picking up her computer, sees e-mails between Maggie and Lucas. Maggie ended their illicit affair a couple of days ago and he’s been trying to get her back ever since. After screaming at her best friend, Jen storms out, only to hear, seconds later, something dreadful happen to Maggie. When she opens the door, Maggie is dead.

The police bring Jen in and are none too convinced that she didn’t have something to do with Maggie’s death, seeing as she had ample motivation to remove her from the planet. But now Jen knows that there may be something to this whole 3-day curse and hurries back to Lucas to get back together with him, at least until she can figure out what the heck is going on. Except Lucas has bad news. “It doesn’t work that way,” he says. Even if they get back together, Jen is already on the clock. In less than 2 days, she’ll be DEAD.

I want to highlight the importance for writers of choosing a concept. Because I looked Jack Follman up and saw that he had one other credit. It was for a movie called “Snorkeling.” Here’s the description for that film: “An authentic coming-of-age film about love, addiction, and mental health. A young couple tries a new hallucinogenic street drug called Snorkeling which explores the highs, and ultimate tragedy, of drug dependency, via a unique journey of adolescent self-discovery.”

Okay, now here’s the description of today’s story: “A young woman finds out, after breaking up with her boyfriend, that everyone who breaks up with him dies exactly three days later.”

I’m placing the producer hat on you right now. You have 10 million dollars. You HAVE to make a movie this year. The above two movies are your only choices. Which one do you make? Is it even a question? Of course you pick “It’s Over.” “It’s Over” is 100 times more marketable – not an exaggeration – than “Snorkeling.” If you don’t understand why, I guarantee you, you’re picking bad ideas to write about.

I’m not saying Snorkeling can’t be a movie. I’m saying that this business is hard enough even when all the factors are in your favor. So why not pick a concept that has wide appeal? That gives you a chance to break out?

It’s Over is one of the better concepts I’ve come across all year. It’s “It Follows” meets “The Ring.” What a great salable combo. Oh, and one other thing, IT’S INCREDIBLY CHEAP TO MAKE. I can’t imagine a scenario where this DIDN’T sell. That’s how perfect of a concept it is.

The great thing about a great concept is that all you have to do is not screw up the execution. Contrary to popular belief, you don’t have to write a great story. You only have to write a great story if you have a concept like “Snorkeling.” But with great concepts, the producers, in a lot of cases, are already leaning towards buying your script/story before they’ve read it. Cause they know how movie marketing works and they know that this is a concept they can sell to audiences.

It’s Over starts out great.

I’ve been doing a lot of consultations lately, which allows me to see things more clearly. It’s easier for me to notice patterns when I’m consistently analyzing scripts. One of the things I’ve been noticing is that writers aren’t taking advantage of their concepts enough.

They’re writing up the kinds of scenes (and scenarios) that can be in any movie as opposed to asking themselves, “How can I write scenarios that specifically take advantage of my unique concept?” The more you do that, the more your story will stand out from the pack.

There’s a great example of that here. Jen’s best friend, Maggie, has been sleeping with her boyfriend. Now, we’ve seen friends sleeping with character’s boyfriends in a lot of movies, right? This is not a new plot development.

However, within the construct of this premise, it’s the perfect development. Cause what it means is that Maggie and Lucas were in a relationship. Therefore, if she just ended it with him, that means she will die. This works as a catalyst to solidify to Jen that what Lucas is saying is real. Cause when Maggie dies, that’s proof he was being truthful.

As soon as I read that scene, I knew, “This writer gets it.” More writers need to do this. I’m telling you – you get so much more mileage out of your screenplays when you do.

So I was upset when, later on, Jen gets stuck in a bathroom and hides in one of the stalls, and the evil “It’s Over” beast starts kicking down the stalls one by one. It’s a scary scenario, sure. But this WAS NOT a scene specific to this premise. This scene can literally be in any horror movie out there (and is). So it doesn’t work the way the Maggie reveal does.

It’s a reminder to keep pushing yourself. Don’t pat yourself on the back after the Maggie reveal and say, “I’m good now.” Keep trying to come up with scenarios that take advantage of your specific premise. That tip is creeping into my top 10 all-time screenwriting tips. That’s how important it is. And yet very few writers actually do it.

The rest of It’s Over does a decent job wrapping up the story but it’s one of those deals where the couple has to go find someone who started the curse and figure out how to reverse it. That scenario needs time to breathe and, unfortunately, short stories are good for letting things breathe. You have to wrap stuff up quicker. You can feel that pinch as Follman attempts to do it. Still, the execution is more than adequate.

There are a lot of sales in Hollywood that make you scratch your head. This is not one of them. This is the sale you read and you go, “Yeah, I know exactly why that sold.”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If a scary scene you just wrote can appear in any horror movie, you need to get rid of it and replace it with a scene that can only happen in your specific movie due to your specific premise.