Search Results for: 10 tips from

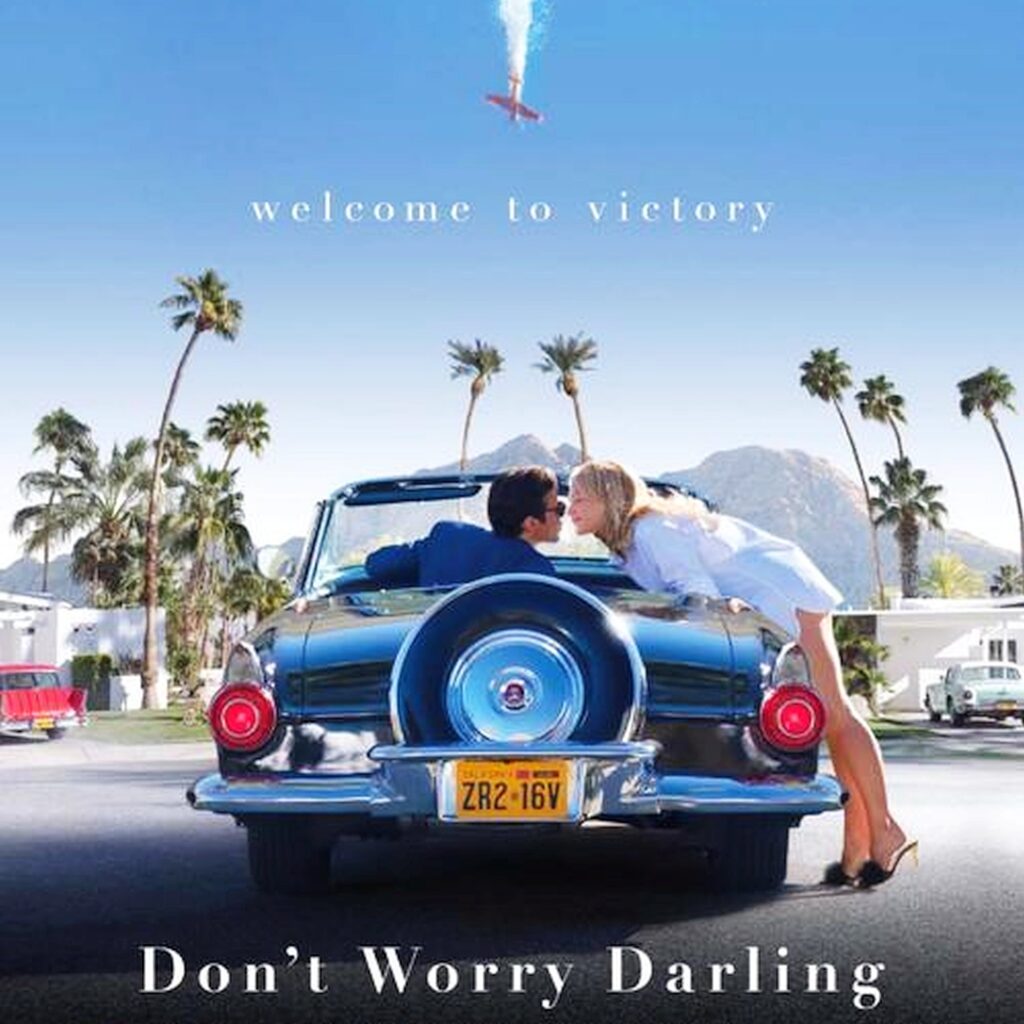

In this review, I’ll not only discuss if Don’t Worry Darling is worth checking out. I’ll reveal a potentially epic twist ending that the director and writer missed out on.

Genre: Drama/Sci-Fi

Premise: (from IMDB) A 1950s housewife living with her husband in a utopian experimental community begins to worry that his glamorous company could be hiding disturbing secrets.

About: After an endless amount of drama – Spit-Gate, Pugh-hate, Shia LaBeouf no longer being your mate — that became so obsessively covered that when it was reported Florence Pugh could only stay 15 minutes at the film’s Venice premiere because she was filming Dune 2, other news outlets questioned why Dune 2’s other big star, Timothee Chalamet, was able to come to the festival for an entire day — Don’t Worry Darling finally came out this weekend and made 20 million bucks. It was a haul nobody in the media liked because they couldn’t spin it into a good story. Had the film bombed, it would’ve been a perfect final chapter to all the behind-the-scenes drama. If it had been a hit, it would’ve been the ultimate redemption story. But, instead, it ended up right there in the middle at the amount everybody expected it to make.

Writers: The original script was written by brothers Carey and Shane Van Dyke. Olivia Wilde then brought in her Booksmart writer, Katie Silberman, to rewrite it.

Details: 2 hours long

Some would argue that the drama that went on behind the scenes of Don’t Worry Darling amounted to a better story than what ended up in front of the camera. The project is a rare studio release that came from a naked spec script sale, which is why I’ve been disproportionately obsessed with it.

Director Olivia Wilde, who had been unofficially propped up as Hollywood’s “Me Too” spokesperson after her beloved “you go girl” freshman picture, Booksmart, won the hearts and minds of Rotten Tomato critics, was set to level up with this movie, which was set to promote the power of feminism through its not-so-subtle message that men are a bunch of controlling jerk-faces.

I was particularly interested in how Wilde would approach the rewrite. For the record, I felt the original script was simplistic. And after seeing the excellent trailers for Wilde’s movie, it looked like she had solved that problem. The movie looked much deeper and more nuanced than the screenplay, which only increased my interest.

It’s the 1950s. We meet Alice and Jack, a very in-love young couple who live in a new community out in the desert. It’s run by this guy named Frank, who’s sort of like a 50s self-help dude on steroids.

After one of Alice’s friends tries to kill herself, Alice starts to question her own happiness and begins looking deeper into this Frank guy. He’s so smug. He’s so sure of himself. There’s something off about him.

After Alice spots a plane crashing in the desert, she heads off to help, only to find a strange house in the middle of nowhere. It’s here where she starts to suspect she’s not living in reality.

After her friends beg her to stop questioning Frank’s utopia, Alice finally learns the truth. (SPOILERS!) She’s living in a simulation, placed in here by Jack because she was too busy with work in the real world and never had time for him. So now she’s got to get out. But is it too late?

A photo more meticulously staged than The Last Supper.

A photo more meticulously staged than The Last Supper.

I was curious how Wilde was going to change the story from the original script.

She stated, in interviews, that she liked the original idea but implied it wasn’t up to par. Which is why she brought in her own writer. I agree with her that the spec wasn’t up to snuff. But now you’re on the clock. If you’re going to change it, you better make it better. Did she?

[Major spoilers follow]

In the original script, there was no question we were in the 1950s. And it was a “clean” 1950s. It wasn’t some special community. The reason that was such a pivotal choice was that it made the twist truly shocking. When we find out that it’s actually the 2040s and the 1950s world is a simulation, it was a big “WHOA” moment and the reason that the script became such a big deal.

For reasons I’ll expand on in a second, Wilde and Silberman ditched that. Instead, they created this situation whereby a bunch of people got up, left their lives, and went out to live in an isolated community. In one of a handful of badly written aspects of the script, it’s never clear if the people in the community left their modern (2022) lives to live this 1950s life, or if they left their 1950s life to live an even more isolated 1950s life.

Right there, you’ve committed a major script faux pas. You’ve made something that didn’t need to be complex unnecessarily complex. And I know the rationale for why they did it. They did it because they couldn’t have characters mixing with the rest of society. They couldn’t have them wanting to go on vacations or explore the world or head down to San Diego. So they created this isolated town in the middle of nowhere where nobody could ever leave. It allowed Wilde and Silberman to have total control over their characters.

The problem with this is, we know the twist pretty much after the first 10 minutes. We know this place is artificial because you’ve got a radio station that talks about tech-y things and you’ve got men who walk around in red jumpsuits and you’ve got husbands who go off to a secret Marvel underground base every morning.

You’ve tipped your hand before you’ve even got to the inciting incident.

The way you pull off a big twist is to not tell us any of these things. Which is the one thing that the original spec got right. They made us believe we were living in the year 1954. So that when we wake up in 2050, we’re like, “HOLY S#$%.” It was a total shock

Wilde almost made up for this weak choice by inventing the character of Frank, played by Chris Pine. Frank is like the world’s biggest self-help guru, to the point where he’s built his own community so he can infuse every aspect of his philosophy into the townspeople.

As the script goes on, this rivalry begins to emerge between Frank and Alice, taking a narrative that was fast decaying and resurrecting it. There’s a really fun scene late in the movie where Alice attempts to take Frank down in front of all her friends – to prove that he’s manipulating and lying to them. When the script focused on those two, it worked.

And about three-quarters of the way through the movie, I realized why Wilde had changed the original screenplay. This new character, Frank, infused the story with an omnipotent malevolence. There’s even a scene where Alice and Jack sneak off to have sex during Frank’s party and Frank catches them. He and Alice lock eyes in a sexy but uncomfortable way as she’s having sex with Jack but Jack never sees this.

And I thought, oh my God, Olivia Wilde came up with a way better final twist! That’s why she changed the original spec! I was convinced that instead of Alice waking up and finding out that Jack had incapacitated her to keep her in this virtual world, instead, Frank had created AN ENTIRE WORLD in order to control and be with all of these women.

I thought we were going to find out that none of the husbands were real. They were all Frank’s virtual creations, bodies he could slip in and out of whenever he wanted, allowing him to be with all of these woman. It’s basically the original twist, but on crack.

“Frank’s 1950 Simulation Pleasure Matrix.” Now THAT would’ve been a great twist.

But, instead, they stayed with the original twist, showing that Alice was being kept in a coma by Jack in his apartment so he could control her. Which no longer worked because you basically hinted that something like this was going on all the way back on page 10 and then kept telling us over and over again that it was coming. They found a way to neuter the twist as much as possible. Wilde may have introduced a new screenwriting term – the “twist neuter.”

But probably the biggest surprise here was that Wilde did a poor job conveying the original feminist message of the screenplay. Which is strange because the original screenplay was written by two men. And the rewrite was written by two women. So you’d think that Wilde and Silberman would’ve gotten that right.

The original script leaned hard into toxic masculinity and men wanting to control women. You don’t get that sense here. Jack was super in love with Alice. He’d clearly do anything for her. Sexually, he was more interested in pleasing her than her pleasing him. If the idea was to convey that Jack was this awful toxic male who wanted a robot for a wife, they did a really poor job of it. The original script made that much clearer.

Also, Alice’s best friend in the film, Bunny (played by Wilde) – it turns out she knew she was in the simulation all along. She actually CHOSE to be in the simulation because, in the real world, her kids died. Here, in the simulation, she could have her kids be alive.

So, wait a minute. Is this simulation designed so that men can imprison their wives and make them their virtual slaves, as was the focus in the original script? Or is this an “anything goes” simulation, where you can come here for whatever reason you want? Cause it sounds like the latter. And, if that’s the case, what the heck is your movie about?

It was sloppiness like that that kept intruding upon a really cool concept. Which made it frustrating.

But you know what?

I still recommend this movie.

And let me tell you why.

The cinematography and, overall, vision of the film, is really strong. Wilde deserves a lot of credit here. There’s a scene early on in the film where Jack and Alice are doing donuts in their car in the desert. It’s filmed from above and it’s not only beautiful, but it CAPTURES THE MOMENT. These were two drunk and in love people just enjoying each other’s company. That camera shot sold that better than any other shot they could’ve used. And there were a dozen moments like that in the film where the visuals truly sold the moment.

Definitely should start worrying, darling.

Definitely should start worrying, darling.

I also loved Florence Pugh. Even when the script hit choppy waters, she was a ship-steadyer. She’s just a great actress and she’s always 100% committed to her performance. She *was* Alice here. Just like there’s suspension of disbelief in screenwriting, there’s suspension of disbelief in acting. If the acting is weak, we’re pulled out of the movie. Florence Pugh is the opposite of that. She’s so in it we can’t help but be in it with her.

Chris Pine is also superb. I love him as an actor and I love him here. My only complaint was that he wasn’t in the movie enough. I get the feeling that if they had a couple more drafts, he would’ve been more present and we would’ve gotten that awesome final twist.

Even Harry Styles is solid. I’ve heard a lot of people say he’s a terrible actor but I didn’t see that. Who knows? Maybe all that extra attention Wilde gave him in the trailer resulted in him picking up a few acting tips. I suppose there’s a method to every director’s madness.

And then you gotta give credit to Wilde. She’s the one who cast these actors. She came up with the overall vision of this movie.

It’s just that the script wasn’t there. And, hey, welcome to the hardest part of making a great movie – writing a great script. Wilde is not alone in falling short in that department. She’s another casualty of the elusive puzzle that is nailing the screenplay

But I was right there with Alice all the way until the final frame. And for that reason, I say this film is worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You don’t want to mess with a good twist. Good twists are rare. I come across one or two of them a year in the screenplays I read. Where I genuinely think, “Whoa. I did not see that coming! That was great!” So when you have that, you don’t want to overthink it, which is what Wilde and Silberman did. When you tell us at the outset that we’re in an artificial community, you put the audience on guard that something funny is going on. And it totally killed the power of this twist. Cause you’ve already put us on the “twist lookout” 70 pages earlier.

I’ve been working hard on my dialogue book.

One of the most frustrating things about writing the book has been finding recent movies with good dialogue to reference! Most great feature film dialogue went out the window in the early 2000s with the death of the indie film. If any of you have suggestions for good dialogue movies post-2015, I’d love to hear them in the comments.

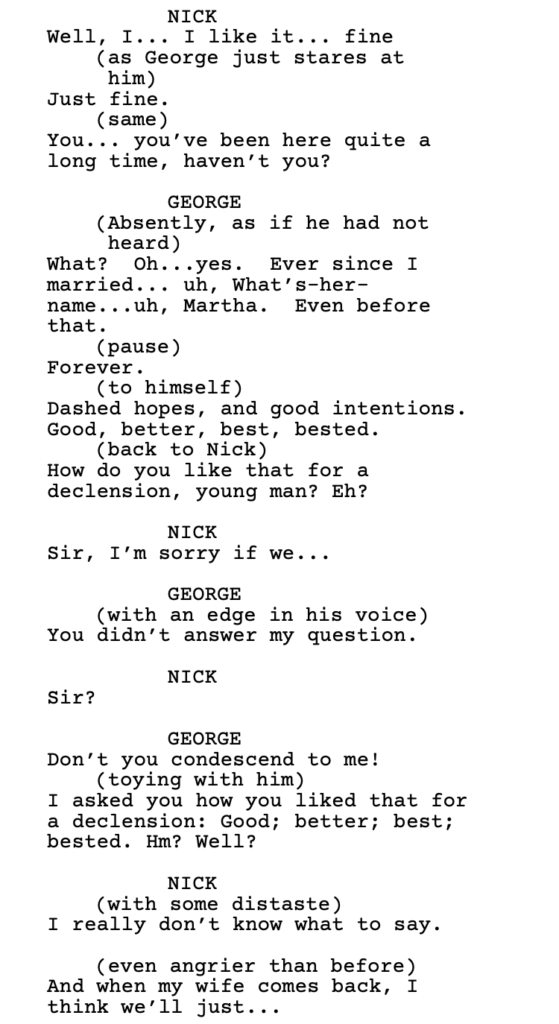

For this reason, I decided to go in the opposite direction and throw in one of the most famous dialogue movies of all time and one I’m not intimately familiar with – Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf. I think I even did an article about this movie years ago but I don’t remember a lot from the film other than the characters all seemed very angry.

Rewatching it was strange because I’ve been writing all of these dialogue tips in my book, believing they were inarguable, only to realize after Virginia Woolf, that there’s more to this dialogue thing than meets the eye.

A rule I was absolutely certain of was that, going into a scene, at least one character needed to have a goal. I didn’t think dialogue could survive without that. Because, otherwise, people are just talking to fill in the space. There’s no purpose to what they’re saying.

Well, with Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, which is about an aging couple who works at a prestigious university and a young couple who come by for some late-night socializing – I realized that this divine dialogue truth wasn’t as universal as I thought.

The characters here would often speak without a clear goal, and for long periods of time. In fact, there were even moments where characters only spoke to break the silence. I mean I guess you can say that “breaking the silence” is a goal, so maybe my precious rule is still in tact. But I didn’t think that a scene could survive when the goal was that weak.

As I continued to watch the movie, I realized that there was one dialogue truth that is always present – and that is CONFLICT.

This whole movie is slathered in conflict. There isn’t a single frame that doesn’t have it. So even though the characters are not always speaking with purpose, the dialogue is still entertaining due to the fact that conflict is present.

And it’s conflict on multiple levels, which I think is the reason it’s able to be so good in spite of its lack of clear goals. If you’re doubling up on conflict, that extra dose could be the substitute you need for a goal-less scene.

What do you mean “doubling up,” Carson?

For starters, the central married couple, Martha and George, hate each other. She hates him because he’s not enough of a man (by the way, this is the first fictional story I know of that implores the insult, “Simp”). And he hates her because she’s constantly cruel to him (not to mention, her college president father’s superior presence always hangs over him).

This creates the undercurrent of tension in every scene. It is, what most people refer to as, “subtext.” Even without saying anything, they’re already saying stuff.

Then this young couple comes along with their perfect young bodies and whole life in front of them and it just sets George off. He uses them, then, to spit out various levels of provocation and frustration. That’s where the second level of conflict is occurring – on the surface.

This doubling down ensures that every line of dialogue has bite to it. Here’s a scene from early on in the movie where Nick, the young professor, is starting to get prickly in response to George’s aggression…

I think the issue I’m grappling with here is that while there isn’t an obvious purpose to George’s interaction with Nick – George is not, for example, trying to get Nick to invest in a business venture of his – I’m wondering if there’s some directive to this conversation that can be quantified, and therefore taught.

George is obviously riling Nick up. That is his internal “goal” in the moment. But why? And is it something that I should be teaching writers to do? Have their characters start sh@# with other characters for no reason. Yes, you get conflict-heavy dialogue. But it’s without structure, without a point.

I think that Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf pushes up against that older belief that movie dialogue should mirror real-life dialogue. In real life, people are mean to other people because they hate themselves or hate their life and they’re just stirring the pot to stir it. They don’t have some divine goal in the moment other than to spew out their thoughts and hurt someone else.

Even as I’m writing that, I go back to this idea of: well, maybe all good dialogue does have a goal, then. Because isn’t trying to hurt someone with your words a goal?

In digging a little deeper, I noticed that while there isn’t some big goal George is trying to achieve, he is a LEADER. He is pushing the scene forward. And that’s worth bringing attention to. Because maybe the real baseline to good dialogue is that someone is pushing the scene forward. George is a force here. He is trying to agitate and aggravate Nick. We’re then curious to see if Nick will crack or fight back. Maybe that’s enough.

What you don’t want in a scene is two characters who are passive. The only thing worse than one character who tries to stir sh#@ up for no reason is zero characters who try to stir sh@# up for no reason because then the scene is lifeless.

Another complication to figuring out this odd movie is that it was originally a play. In plays, you have to fill up 90 minutes of talking somehow. Movies are more visual, which allows you to do more showing than telling. So is this just a case of a playwright filling up space with dialogue cause he has to? Dialogue that wouldn’t normally be in a movie?

I’m going to keep working on this because it’s my belief that the best dialogue has purpose. And that purpose comes from a character who has some sort of goal or “want” in the scene. I may have to dig deeper into Virginia Woolf to see if the film is, indeed, achieving this and I’m just missing it, or if there are deeper secrets yet for me to learn about dialogue.

In the meantime, feel free to provide your own thoughts on this movie, your own suggestions on good dialogue movies post-2015 from screenwriters not named Tarantino (I’ve got enough of him in the book). Share your own dialogue tips. And leave suggestions on what aspects of dialogue you want explored in the book. Feel free to share your dialogue struggles as well. The more I know about what perplexes you guys, the better I can make the book.

Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf is on HBO Max.

$50 OFF A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – The Labor Day deal may be over but you can still save some money on a script consultation! I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to both fix your script and improve your writing. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!

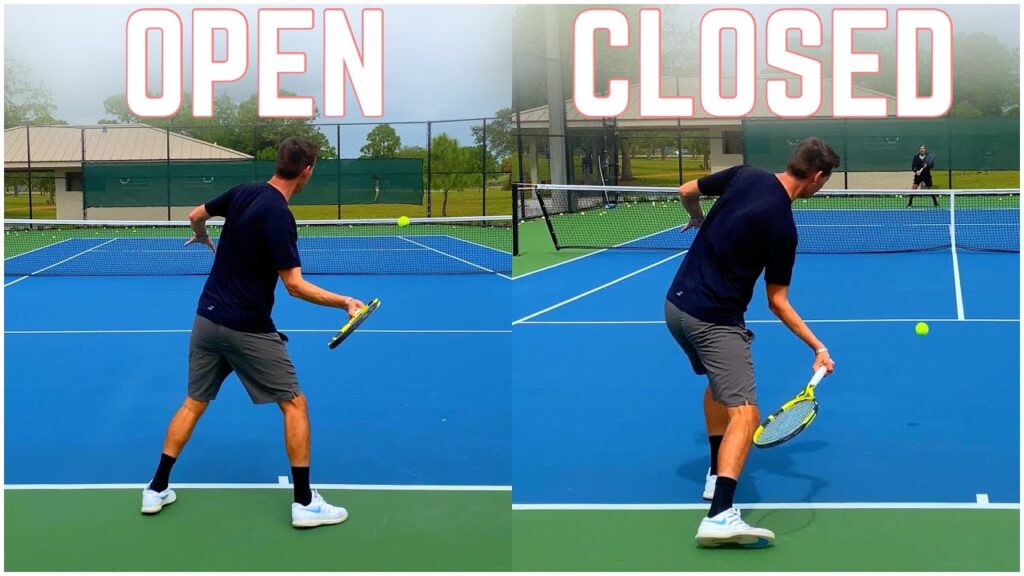

Ever since I got into screenwriting, I’ve been hearing the same pieces of advice over and over again. Normally, when advice is repeated frequently, and by lots of people, it means there’s something to it. I know, as a tennis player, that the advice, “Watch the ball,” is just as relevant today as it was when it was first given, back in the 60s.

With that said, there are definitely some tennis tips from that era that are no longer applicable today. For example, it used to be that when you wanted to hit your forehand, you would step in with your left foot, turn your body, and swing forward via a “closed” stance. These days, pros will tell you to actually step sideways with your right foot, as it helps create more of a “coil” effect while swinging, which adds power.

This got me thinking I should reconsider all that classic screenwriting advice that’s been given over the years and decide how relevant it is in 2022. I suspect some of you are going to get triggered by my thoughts, as you sometimes do whenever I talk about these topics. Feel free to let your She-Hulk-sized rage out in the comments.

ADVICE: “The best way to be a good writer is to experience life.”

THOUGHTS: I’ve always had trouble with this advice because it’s vague and, therefore, not actionable. Going back to our tennis analogies, it would be like if I said, “Focus on being more present during the point.” Sure, that helps. But there’s no actionable advice there. I will say this. One of the main problems I see in the screenplays I read – both amateur and pro – is a lack of specificity. Writers write characters and scenes and plot points that they’ve seen before in other movies. Instead of writing original stuff. The way that you write original stuff is to base your scripts and your stories on your real-life experiences. If you lived in Morocco for a year, you can write a story about a unique place with a level of specificity that very few writers can. This is how Alex Garland broke onto the scene. He wrote a novel called “The Beach,” that was based on his own experiences traveling through Thailand. Could he have written as good of a book had he never been to Thailand? Probably not. The more you’re drawing from your own personal experiences, the more original your stuff is going to be. And the more life you live, the more of those experiences you’re going to have.

RATING: 9 out of 10

ADVICE: “Keep your script under 120 pages.”

THOUGHTS: My initial reaction to this advice is yes. And, actually, you should probably keep your script under 110 pages. The main reason for this is to keep the read under a certain amount of time. Readers have a set block of time allotted for script reads. Somewhere between 90-120 minutes. When you force them to go over that allotted time, they get very angry. Which is why a lot of readers will go into a script furious if they see the page count is over 120. With that said, screenwriting is a strange beast. I’ve read plenty of scripts that have been over 120 pages and have read quickly. And I’ve read plenty of scripts that were 90 pages that took forever. That’s because the type of writing tends to have a bigger effect on how long the read is than the actual page number. If someone writes in long chunky paragraphs and a lot of their script lacks clarity, forcing the reader to stop and re-read sections, those are the scripts that take 2 and a half hours to read. But if someone writes 2-line paragraphs and is a great storyteller, a 90 minute read can feel like half an hour. The truth is there’s a psychological component to that number (120) that readers just don’t want to see north of. Do so at your own risk.

RATING: 8 out of 10

ADVICE: “Concept is king.”

THOUGHTS: Whenever I hear this advice, my initial reaction is, YES! 10 OUT OF 10 YES! But like all advice, the devil is in the details. A big sexy high concept (High Concept Showdown coming in December!) does so many good things for you, the biggest of which is it’ll get you a lot more reads than a small concept. The more people who read something, the more bites you get at the apple. But I must admit, the main way screenwriters get recognized in 2022 is through the Black List. And the Black List has just as many average concepts as it does good ones. So how important can concept be? I thought about this for a while and I think I know the answer. Even though there are a lot of scripts on the Black List that don’t have sexy concepts, they still fit into the boxes that the Black List likes checked. If there’s something trendy, like socio-political horror in 2019, you don’t have to have a great concept. That script is going to get read because it’s on-trend. We know the Black List loves biopics. We know they like LBGTQ stories. Which is a long way of saying that these writers aren’t just writing whatever low-concept inspires them. They’re still being calculated with the concepts they’re choosing. Which means that concept is still king.

RATING: 8 out of 10

REMINDER!!!

What: AMATEUR SHOWDOWN – HIGH CONCEPT EDITION

When: Entries due December 1 by 8pm Pacific Time

How: E-mail me your title, genre, logline, any extra pitch you want to make about why your script deserves a shot, and, of course, a PDF of the screenplay.

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Anything else?: You can start sending in your scripts right now!

ADVICE: “You have to move to Hollywood if you want to succeed as a screenwriter.”

THOUGHTS: If you dropped this bomb in a screenwriting message board in 2003, you would come back the next day and find at least a dozen commenters banned. This advice used to get so many people riled up. And it’s understandable why. If you didn’t live in Hollywood and somebody told you that the only way to make it was to live in Hollywood, you’re going to fire some shots. The good news is that, with the evolution of the internet, the digital screenplay, and, most recently, Covid, you don’t need to live in Hollywood anymore to make it. I know people here in LA who would rather jump on Zoom than meet in person. That’s how used to virtual meetings people have gotten. With that said, if you want to be a TV writer, it’s still highly advantageous to live here. Because they want people who are going to be in a physical writer’s room together. And even if you’re a features writer, it helps to be able to meet people in person. You make more of an impression that way. Not to mention, continued real-life contact develops stronger relationships that are more likely to lead to working relationships. So, yes, it’s still preferable that you live here. But it’s by no means required.

RATING: 6 out of 10

ADVICE: “Every screenplay should have three acts.”

THOUGHTS: There was a time, back in the destructive 90s, when vagabond writer-directors like Quentin Tarantino were turning screenplay structure upside-down. Stories were being told out of order. Scenes would go on forever. Conflict, not structure, seemed to be the name of the game. Anyone writing in three acts, at the time, was considered lame. But it was interesting what happened after that. You had a bunch of writers who came into the craft writing without rules and movies quickly devolved into giant messes. It turned out not everyone was as talented as Quentin Tarantino. All the 3-Act structure does is give you 25 pages of set-up, 50 pages of conflict, and 25 pages of resolution. Do you have to use it all the time? No. But you’re going to use it in 95% of the screenplays you write. So it’s something you want to learn and you want to depend on.

RATING: 8 out of 10

ADVICE: “Outline, outline, outline.”

THOUGHTS: I don’t know why outlining is so controversial but it is. If I had to guess, I’d say that the people who don’t outline get really mad when you tell them they should outline. The implication is that they’re skipping a step and it’s making their screenplays worse. So they feel like they have to intensely defend their point. But in speaking with several newbie screenwriters over the past month, I learned something. Cause I told them they should be outlining and they came back with… “How?” My response was, “What do you mean, how? You should outline so that you have a sense of where your story is going and you don’t run out of story midway through the script.” Still, they looked back at me blankly. After some back-and-forth, I realized that a lot of beginners aren’t even confident in their understanding of the three act structure. If you don’t even know that yet, coming up with a well-structured outline is next to impossible. What this taught me was that you need to write a few screenplays and get a feel for the pacing and the structure before you can effectively start drawing up outlines. Maybe you’re one of the lucky people who have an intrinsic understanding of structure and, therefore, will decide you’ll never need to outline. That’s fine too. But I still think that, for most screenwriters, outlining helps more than it hurts.

RATING: 7 out of 10

ADVICE: “Nobody knows anything.”

THOUGHTS: Everybody loves quoting this line, even me. But I’ve found this line to be more dangerous to screenwriters than helpful. That’s because a lot of writers use it as an excuse to throw the rules away. “I don’t have to make my hero likable. NOBODY KNOWS ANYTHING!” The reality is, people know a lot of things. Those folks on the top of the Hollywood food chain? They know a sh#t-load about writing and making movies. If you’re going to get where they are, you have to learn what they’ve learned and incorporate those lessons into your scripts. It’s doubtful you can succeed by ignoring everything and writing whatever random thoughts accumulate in your head when you’re in the midst of a writing session. Become someone who knows something and you’ll have a much better shot at success.

RATING: 4 out of 10

ADVICE: “Writing is rewriting.”

THOUGHTS: If I’m being honest, I don’t know why rewriting is so heavily depended upon in the craft of screenwriting. Rumors are that there were 100 drafts of Good Will Hunting. The Safdie Brothers said they wrote 200 drafts of Uncut Gems. My issue with those numbers is that I’m not sure it’s the best use of your time – endlessly rewriting one script. I do think rewriting is important. But the truth is, if you do the work ahead of time (do a very detailed outline of your story), you won’t have to do as much rewriting on the back end. The question is, how many drafts of a script should you write? That’s impossible to answer because each writer is different, each script is different, and each rewrite is different. Is your first draft a complete miscalculation? If so, that script will have to be rewritten more than one where you got pretty close to your original vision on the first go-around. I think ten drafts should be the ceiling for an advanced writer. 15 drafts for an intermediate. And 20+ for newbie writers. Keep in mind, that’s what Ben Affleck and Matt Damon were when they wrote Good Will Hunting. They were newbies. So they needed more drafts to figure it out. But what you definitely don’t want is the forever rewrite. Get the script as good as you can make it and then move on to the next one.

RATING: 7 out of 10

$150 OFF A SCRIPTSHADOW SCREENPLAY CONSULTATION! – To the first person who e-mails me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: “150.” I have a 4 page notes package or a more detailed 8 page option designed to both fix your script and improve your writing. I also give feedback on loglines (just $25!), outlines, synopses, first acts, or any aspect of screenwriting you need help with. This includes Zoom calls discussing anything from talking through your script to getting advice on how to break into the industry. If you’re interested, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s set something up!

So late last month, a little known E.T. story started making the rounds. Steven Spielberg had finished 1941 and was currently on production of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Like any smart director, he was lining up his next film, E.T., and needed a writer. As luck would have it, he wanted a young writer named Melissa Mathison, who was his star’s (Harrison Ford) girlfriend at the time.

This is where the story gets interesting. Spielberg pitched Mathison the idea for E.T. and Mathison said no, she didn’t get it. I just want to pause here so we can all hear the galactic level record scratch of a writer SAYING NO TO STEVEN SPIELBERG! In Mathison’s defense, she had a good reason for the rejection. She’d just quit screenwriting.

Between her two lone credits, The Black Stallion and The Escape Artist, Mathison had decided that screenwriting was “too hard.” In retrospect, Mathison’s early retirement never stood a chance. Spielberg went straight to Ford, asked him to put in a good word for him and E.T., and Mathison eventually came around to write the film. For all involved, it was ‘happily ever after.’

However, Mathison’s reason for the initial rejection stuck with me. She quit screenwriting, at just 31 years old and with two produced credits, because it was “too hard.”

“Too hard.”

Is screenwriting “too hard?”

It sure seems easy when you’re watching a bad movie. “I could write a better movie than that!” somewhere north of 100 million moviegoers have said over the years.

But anyone who’s spent even three years in the game knows how deceptively difficult screenwriting is.

But is it too hard?

Is it not worth the trouble?

A while ago I was developing a sports script with a writer and we’d spent countless hours and many drafts trying to figure out our main character. It seemed like every new draft, we tried a new iteration of the character. After about draft 7, the character finally started to take shape. We finally felt like we understood him, and the rest of the script came together nicely as a result.

Then, around draft 10, as we were writing the big final game, it occurred to us that the ending would be MUCH BETTER if our main character made a major sacrifice at a critical point late in the game. We’re talking, the climax went from being a 6 out of 10 to a 9 out of 10. The change was a no-brainer. We had to do it.

But here was the problem. Our main character was not someone who sacrificed. Nowhere in the script was this built into the character so that when the moment came, it would make sense for him to sacrifice anything.

What we realized was, if we were to write this new direction into the climax, it would mean completely redesigning the character from the ground up. He’d have a totally different personality and demeanor. Which would make all of his actions and dialogue different.

On top of that, we’d designed the love interest to be in stark contrast to our main character. She was his opposite. By changing the main character into this new version, he was no longer the opposite of the love interest. Which meant – as I’m sure you’ve already figured out – we’d have to completely rewrite her as well! Change her from the ground up so that this new version of her was opposite to the new version of him.

So now we had to sit down and make a difficult decision. Do we make all these changes, redesigning our two main characters from the ground up, just to support this awesome ending? Or do we continue to try and find another great ending, despite the fact that we’d spent the previous six months doing just that and failing?

Is screenwriting hard?

If you’re doing it right, you bet your ass it’s hard.

So I get Melissa Mathison. I totally understand where she was coming from. Because a script can feel like a never-ending battle. In a way, you never truly write the script you want. You either run out of steam or, if you’re one of the blessed few who have made it to the professional ranks, they need to start shooting.

With that said, I have found some tips and tricks over the years to make the experience of writing screenplays a little easier. If you incorporate these ten tips, you’re going to keep more hairs on your head, and severely lower your chances of having a heart attack.

Outline – One of the things that causes so much pain in screenwriting is all the drafts. You’re always having to fix some aspect of the script with a rewrite. You can knock about 3-4 drafts off that process if you outline. In particular, outlining helps you figure out your structure ahead of time, which means spending less drafts fixing your broken structure.

Make sure you understand your 2-3 main characters as clearly as possible going into the script – The hardest thing about screenwriting is getting the characters right. That’s because people are complex and creating fictional versions of them that feel authentic takes an incredible amount of skill. Therefore, if you have a great feel for your characters going in, you eliminate a lot of headaches later on. Rocky is an underdog who doesn’t know if he has what it takes. Alan in The Hangover is the most socially unaware overly opinionated man in the universe. Guy (Free Guy) is tired of following the same old routine every day and decides he’s going to commit to doing things outside his comfort zone. Just like these examples, try and distill your character down to a single clear sentence. If you can do that, you should be good.

Keep your story simple – I read a lot of “everything-and-the-kitchen-sink” scripts where the writer is shooting themselves in the foot by giving themselves a massive amount of variables to keep track of. The reality is, most of the best movies have a simple setup and execution. Small character count. Clear goal. Etc. By keeping the variables down, you’ll keep the stress level down.

Be passionate about your concept – As much as I talk about finding the best idea you can come up with and writing it, that’s worthless advice unless you love the idea. As most of us here can attest to, there is nothing worse than writing a script you’re only kinda into. Every draft feels like five drafts. These scripts take way more out of you and will definitely accelerate any doubts you have about whether screenwriting is for you. Love that idea like you love your family.

Write lean – If you tend to write 4-line paragraphs, aim for 3 lines. If you tend to write 3-line paragraphs, aim for 2 lines. Writing lean means there are less words to edit and since we’re all writers and obsessive about making every little sentence perfect, the less words you have to wade through, the less hassle writing is going to be. As a bonus, your script is easier to read through.

Don’t deliberately make the process overwhelming – You’ve got a document detailing all the characters in your script, a document for your potential story ideas to use, you’ve got your outline, an excel spreadsheet tracking when and where every character appears, you’ve got a document for alternate scenes, a document for deleted scenes, a document explaining the alien language spoken in your script… If all these things make you genuinely happy, fine. But, at a certain point, we make the process of writing a script so cumbersome, that we start to hate the idea of working on it. It’s fine to get detailed. But don’t get carried away.

Focus on the things you should do, not the things you shouldn’t – I know reading this site can sometimes feel like a never-ending mine field of screenwriting bombs to avoid. But if all you’re doing is focusing on mistakes to avoid, you can’t write freely and you won’t have fun. You are always going to do things in your script that “shouldn’t be done,” like yesterday’s choice to make the protagonist a kidnapper. But as long as you feel it’s right for your story, embrace it and don’t look back.

Talk it out – Find someone in your life who will listen to you talk out the problems in your screenplay. One of the reasons writing is so hard is that we contain ourselves to just our brain and run the same problems through that calculator over and over and over again with no result. Of course writing starts to feel impossible (and drives you crazy!). Sometimes you need to talk your ideas out with someone, even if they’re not a screenwriter. By forcing yourself to explain the issue to a third party, you see the problem through their eyes, and that alone helps you find a solution.

Focus on the stuff that matters – Stop stressing about that exposition scene on page 70 where you’re trying to make each dialogue line perfect. Instead, focus on the things in your script that have the biggest impact on the read. The first ten pages, the first act turn, the midpoint shift, the story’s big set pieces, the hero’s low point, any major twist scene, the climax. That’s where you should be placing 75% of your focus. You don’t need to drive yourself crazy over those smaller scenes where the characters reveal some mildly significant backstory about themselves. In the grand scheme of a screenplay, those scenes are way down on the priority list.

Be easy on yourself – Screenwriting is hard no matter what you do. It’s baked into the pursuit. However, I think that’s why we do it. We know that in those few moments where we do crack the code and write a good script, we’ve achieved something amazing, something that very few people on the planet can do. Who cares if you achieve something that’s easy, right? You only feel a sense of accomplishment when you’ve achieved something that’s hard. Maybe even too hard. :)

What’s your take on this? Is screenwriting too hard?

Having concerns about your logline or screenplay? Let me help you. Logline consults are just $25 (and if you buy 4, you get a 5th for free). I also provide consultations for each stage of the screenplay journey: outline ($99), first 10 pages ($75), first act ($149), full pilot ($399), full screenplay ($499). I’ve read thousands of screenplays, including all the ones that get produced and all the ones that don’t. There’s no one better equipped to help you improve your script than me. If you’re interested in getting a consultation, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s work together!

A storyline that got overlooked at the Oscars due to Slapgate was that Apple, not Netflix, took home the first ever Best Picture Oscar for a streaming service! You cannot begin to comprehend how angry this makes Reed Hastings, who has invested truckloads of money coveting high profile directors like Alfonso Cuarón and David Fincher, in hopes of winning that golden statue and legitimizing Netflix. I can only imagine how angry he is that streaming whipping boy, Apple, won their version of the space race.

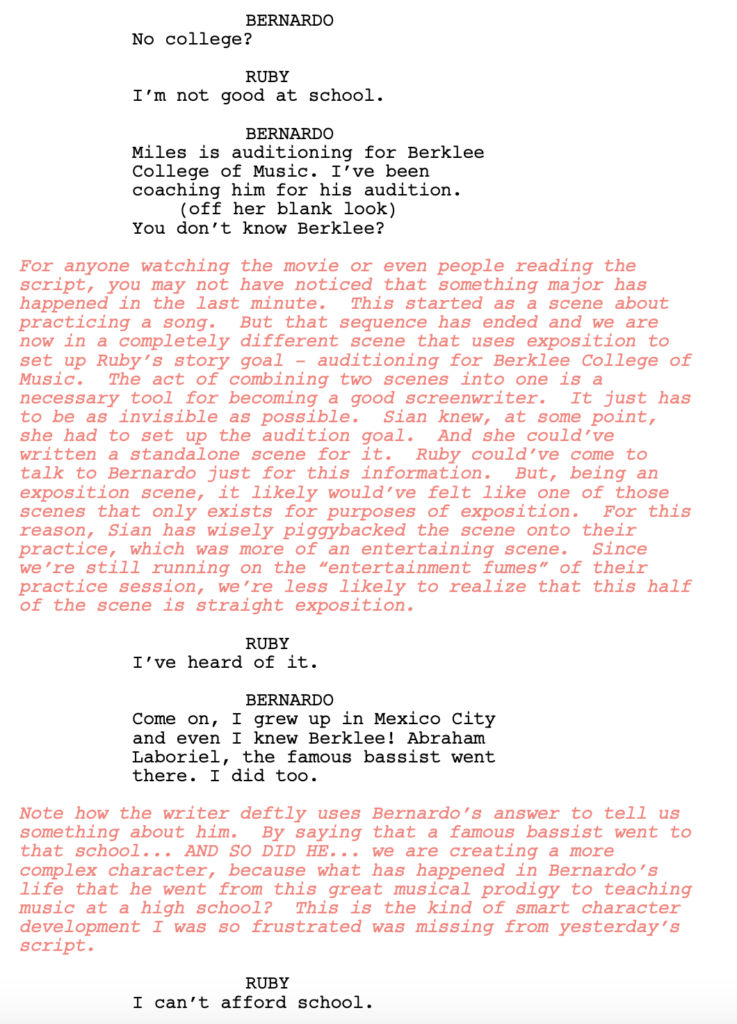

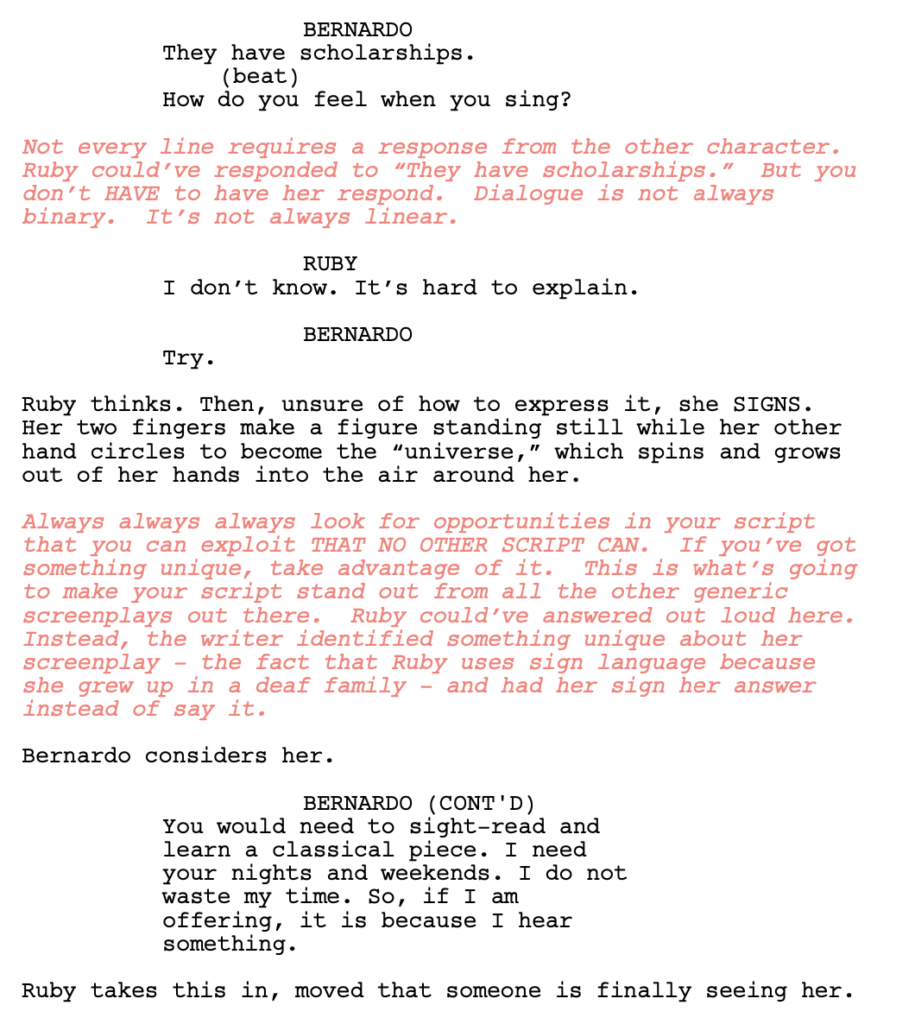

I loved Sian Heder’s, Coda, and thought it was the perfect time to bring back the “scene breakdown” feature I did with “I Care A Lot.” I’m going to highlight two scenes from the award-winning script (which you can download here), and while the focus will be on dialogue, I’ll spotlight a few other screenplay tips as well.

If you haven’t seen Coda, it follows a senior in high school, Ruby, the only hearing member of an, otherwise, deaf family. While you’d think this would make her sympathetic to her parents and brother, it’s the opposite. She’s always been looked at as “the weird girl with the deaf family” and, as a result, felt ostracized.

For the first time ever, Ruby is doing something for herself. She’s always wanted to sing but hasn’t had the confidence to do so. So she’s joined the choir class in high school and the teacher has assigned her to a duet with Miles, a boy she has a crush on. The following scene takes place in their music teacher’s classroom. They were supposed to practice their song together but didn’t.

This next scene takes place 10-15 minutes later in the movie. This is the first time Ruby and Miles are practicing together and they’re doing so at Ruby’s house. Ruby is incredibly nervous about this not just because she has a crush on Miles, but because her family is such a wild card. She’s terrified that this may be a dealbreaker. I can’t stress this enough: Put your characters in situations they’re uncomfortable in. And with that established, let’s take a look at the scene…

And that’s it. I strongly recommend you read this script (it’s only 80 pages) AND watch the movie. Share your thoughts in the comments section, especially any additional lessons you picked up from the dialogue.