Search Results for: 10 tips from

I’ve spent so much time analyzing bad screenplays lately that it’s gotten a little depressing. This would be a good time to remind everyone that I *HATE* giving negative reviews. There are so many more benefits to reviewing good scripts. For starters, I get to read something I actually like. Which is way more enjoyable than trudging through yet another average screenplay.

But I also think you get more out of a good script than a bad one. Sure, it’s great to point out a bunch of things that aren’t working in a screenplay. But all that’s really giving you guys is stuff to avoid. And nobody writes a great script if their only focus is avoiding bad screenwriting practices.

You write great scripts because you’re inspired. And there’s nothing more inspiring than reading a great story. You also get a bunch of actionable tips you can add to your screenplay. Instead of avoiding stuff, you’re implementing new character tips, new plot tips, new scene tips, new dialogue tips, all of which you know work since you’ve seen the proof of concept with your own eyes.

So I’m glad that, at least for a day, we get to celebrate writing. I watched two great shows this weekend. The first was the finale for “Peacemaker” and the second was the new Ben Stiller-directed show on Apple TV called “Severance.” Severance follows a worker, Mark, who agrees to split his consciousness in two halves. The first half exists at work. This version of him knows nothing about his normal life. The second half exists outside of work and knows nothing about his work life.

By the way, what’s cool about this show is that it comes from a first time writer, Dan Erickson. Something I love about Red Hour Productions – Ben Stiller’s company – is that they’re open to anyone who’s got a good concept. You don’t need to be Aaron Sorkin to win them over. Them taking a chance on this neophyte writer is proof of that.

Erickson’s script actually first gained attention when it appeared on the 2016 Blood List. From there, it somehow got to Red Hour. And when Ben Stiller read it, he loved it. Stiller is always looking for things that bring both incredible comedy and incredible sadness and this script had both. Still, it took five years from when Stiller first read the script to make it to air.

Imagine waiting for that as an unknown writer. You’ve got nothing else going on. A major director loves your script but, because he’s so popular, he’s getting pitched new projects every day and, at any moment, one of those projects could catch his interest and become his priority. To wait all that time and see his show come to fruition? That’s the dream we all live for, baby!

If you haven’t seen it yet, it’s one hell of a trippy show. For example, at one point, a new worker at the company says she wants to quit. The place is too damn weird. Mark points out that if she does that, it will essentially mean she’s killing herself. “How so?” She asks. “Well, since this version of you only knows this world (the work world), once you quit, everything that’s ever happened to you here disappears from existence. That version of you would, essentially, be dead.” Chew on that for a while.

Erickson’s rise to produced writer is not what I’m here to talk about, though. I’m here to talk about what makes the show so good. And, more specifically, what makes both Severance AND Peacemaker so good. There’s got to be commonality there, right? Something that explains why these two shows were so much better than all the other trash on TV?

The answer, not surprisingly, is character. But I’m not talking character in an abstract way. I’m talking about a specific type of character. And that is the character who is built around CONTRAST.

While adding contrast to a character does not guarantee that the character will be memorable, or awesome, or compelling, it exponentially increases the chances that those three things will happen.

Let’s look at why. When you have contrast in your character, it means that the character is out of balance. And because they’re out of balance, there’s always going to be conflict within them. That conflict is going to be what makes them interesting.

Let’s say you have a devoted priest who also happens to be a serial killer. For the sake of this argument, we’ll say that he only kills bad people. Think about what this character wakes up to every morning. He has to share the word of God with his followers, despite knowing that he just brutally murdered someone last night. You can’t square that away without being in extreme conflict with yourself.

Peacemaker has a similar issue. His job is to kill people. And yet, in his heart, he’s the kindest guy in the world. This means, like the priest, he’s in constant conflict with himself. It’s never as easy as point and shoot.

You can see the value of this contrast when you compare Peacemaker to his best friend, Vigilante. Vigilante is a fun character. But he’s not compelling enough to be a lead character. “Why?” you ask. Well, Vigilante, like Peacemaker, has one job – to kill. But unlike Peacemaker, he doesn’t care that he kills. He has no resistance to it whatsoever. Without that contrast, the character is fairly one-dimensional and, therefore, only mildly compelling.

Meanwhile, what’s so fascinating about Severance, is that it builds its character around the same concept – contrast – but does so under completely different rules. Mark’s contrast comes from the fact that he’s living two separate lives. The “extremes” come in the form of his home life, where he’s a sad lonely widow, and his work life, where he’s a happy and content company man.

Just to emphasize the importance of contrast, imagine this same setup but Mark was happy at both his home and work life. Or sad at both his home and work life. You need the contrast in order to create the conflict. That’s what creates dramatic questions such as, “Which one is going to win out here? The happy Mark or the sad Mark? Who is going to win out on the tug-of-war for Mark’s consciousness?”

When you don’t apply this contrast to your main character, you get characters like Nathan Drake in Uncharted. To Uncharted’s credit, it did better than expected at the box office this weekend (50 mil if you include President’s Day). But the knock on Uncharted is its excruciatingly vanilla. And “vanilla” is always what you get when you have a hero with no contrast. The fact that nothing’s rubbing up against anything else inside of this person is what’s providing a friction-free journey.

I’m sure some of you are wondering if your screenplay is doomed without contrast. Of course not. Does John McClane have contrast? He wishes he’d worked harder to keep his marriage stable but that’s not contrast. That’s personal family issues. Contrast is easier to avoid in features because you’re only with the characters for two hours and there are other ways to make characters interesting for two hours (such as giving them family issues).

However, it is essential in television that your hero contain contrast because not only are we going to be with your story a lot longer than two hours, but TV shows rely a lot more on character than spectacle, meaning the characters must be more captivating. And one way you ensure that a character is captivating is to give them that contrast. Peacemaker will always struggle with killing. Mark will always be changing back and forth between his happy work life and sad home life.

This is one of the most valuable tools you’ll ever use as a writer and if you can effortlessly integrate it into a character so that the contrast feels organic, you’re going to create a character for the ages.

Today I have a special treat for you, an interview with David Kessler, the writer of the new Johnny Depp film, Minamata, which comes out this Friday! The movie follows photographer Eugene Smith, who famously documented the effects of mercury poisoning on the citizens of Minamata, Kumamoto, Japan. A little backstory on this one – I consulted on the script many moons ago for David. David kindly credits me for helping him get the script in shape for what would, ultimately, become his first major writing credit.

1) Let’s start with you, David. When did you start writing screenplays?

I started writing screenplays in the mid-’90s while living in New York and working for myself as a graphic designer and a copywriter (WFH waaaaaay before it was a thing.)

My first script was a biopic about the 1950’s doo-wop child star Frankie Lymon. I had tracked down the former members of his group, The Teenagers, who were also (still) living in New York and very much not teenagers anymore.

After I had finished spec’ing the Lymon story, it was announced that “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” was going to be made by the director of Selena, Gregory Nava, and that turned my screenplay into 120 pages of scrap paper.

2) Until the point when you wrote Minamata, how many screenplays had you written in total?

Five finished ones (the Lymon biopic, a terrible thriller I have little memory of, a coming-of-age adaptation of my terrible novel, a comedy based on dating, and a rom-com I re-wrote too many times for too long).

Plus 2 TV pilots, 4 TV specs (a Will & Grace, a Curb and two Seinfelds) and a short film. And a handful of feature treatments.

3) What would you say were a few of the most important screenwriting lessons you learned early on that allowed you to write such a good script in Minamata?

That you need to write bad scripts (see above) to get to good scripts. There are very few Sorkin-esque prodigies. It’s a craft. Your first chair is going to be a rickety bunch of wood but your 500th one will be much sturdier (and be worthy of selling).

And always be learning. I read your blog every day and still read screenwriting books and articles, watch YouTube videos about the craft, and screenshot little bits of advice I see on Twitter.

Plus, it may take a few genres / scripts to find what your “lane” is. Even though my first script was a true story / biopic, it took like 18 years to circle back to that niche.

Also, scripts and movies are supposed to make you FEEL something. If I didn’t scare you with a horror story or make you cry with my drama, I feel I failed.

And the bar is really, really high.

I once had a full-time job writing movie poster lines about 15 years ago – I read 2 to 3 scripts a day and these were things in production – Juno, Hancock, Enchanted, Stepbrothers – you realize you gotta be as good as the pros for studios to make your movie instead of Scott Frank’s or whomever’s.

Stepbrothers made me laugh so hard I couldn’t breathe in my cubicle (the testicles on the drums scene in particular). The Mist gave me nightmares after I had read it.

4) For my own egocentric needs, have there been any tips you’ve learned from the site in general that have helped you become a better screenwriter?

Oh tons — I bought your e-book years ago and I read the blog every day and screenshot a lot of your “what I learned”. And often go back through the archives. The Goal, Stakes, Urgency tip I come back to often and I even remember I think Jersey Shore was an influence on that somehow.

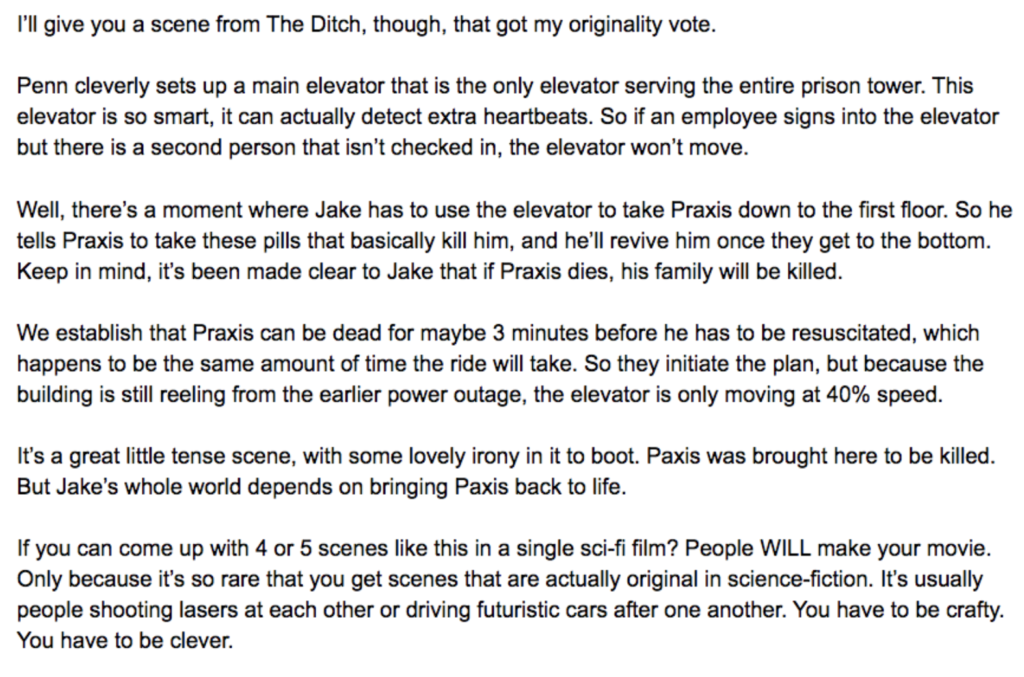

Here’s something I screenshotted back in 2017:

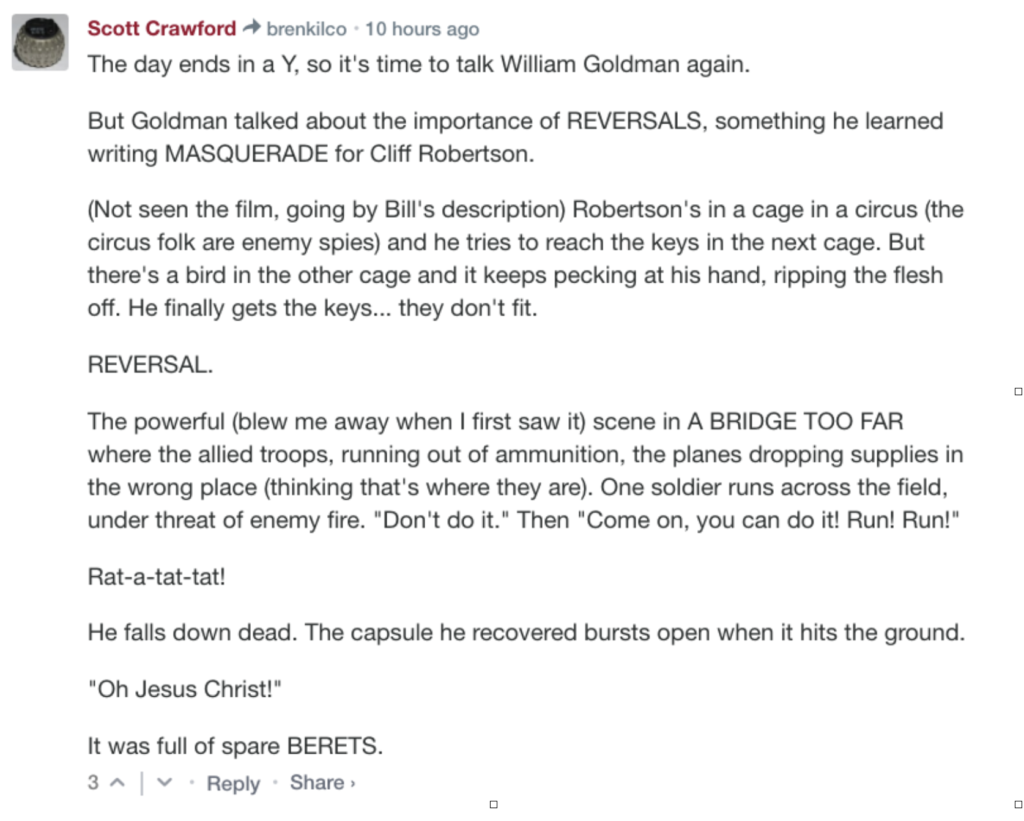

Another from the comments:

5) Now let’s get to the juicy stuff. Here on the site, I advocate for writing genre material with strong hooks. Minamata is a passion piece and, one would argue, the complete opposite of that. What advice would you give to someone who wants to write dramas or “low-concept” material? How do you write in this space and find success, like you did? Is there a game plan one can follow?

That’s hard to answer. Regarding the sale and having it been made, it’s like asking, “How do I win the lottery?” or “How do I find the love of my life?”

A lot of things need to fall exactly in place at the exact right time. I got very, very, very, very lucky.

Once I ran the numbers on the odds of my spec getting made with a movie star of Depp’s stature…I think the number came to .00004%.

I had caught Mrs. Smith (the widow of Gene Smith, who Depp plays in the film) at a time where she was willing to explore a movie deal again (she had been approached many times over the years and even had had meetings with Anthony Hopkins, Ang Lee and Scorsese in the ’80s or ’90s, with Hopkins to play her husband).

AND I had known a person from the comedy world from 13 years earlier who took the sketch class I had but the one right before mine but came to our class’s show – she gave it to her manager. This manager happened to have worked at a photo magazine in the 1970s, so the subject matter sparked her interest.

AND Johnny Depp knew of Gene Smith and admired him and his work because his friend, the late photographer Mary Ellen Mark, had taken Smith’s classes in the 1960s and had told Depp Gene Smith stories…

6) Quick question here: Did you know Depp liked Gene Smith ahead of time or was that pure coincidence?

That was a wonderful coincidence. I was told when Depp was in the office and the staff was updating him on the projects the company was developing, someone said, “Oh, it’s the story about this photographer named W. Eugene Smith who goes to — ” And Depp had (nicely) cut them off and said “I know who Gene Smith is.”

I had no idea about his relationship with Mary Ellen Mark or that she had taken classes from him, most likely at The New School, where I had gone to college.

7) Okay, got it. Continue…

All those people and moments had to have aligned for Minamata to get made (with Depp – see below for the attempted-Jeff Bridges path).

None of this is to say you shouldn’t write your passion project.

About half the projects on The Black List feel like passion projects (some have rights issues that inherently prevent a sale – like, say, the making of The Empire Strikes Back from the guy who played R2D2’s point of view or whatever.).

But they can attract attention. And demonstrate your ability and voice. I seem to recall getting some general meetings off Minamata before Depp’s company wanted it.

Being John Malkovich was probably a passion project / written to (further) showcase Charlie Kaufman’s unique voice. But then Spike Jonze asked his reps for the “weirdest script that could never get made” after he was sick of reading “regular” movie scripts. And Kaufman’s career took off.

So my point is, even if your script doesn’t get MADE, the script could MAKE YOU.

8) How does one get their script to an actor as big as Johnny Depp?

Through the normal, respected channels. My manager knew his “people”.

Someone took a recent script of mine (now granted, this person is married to a ridiculously famous person) and put it in the mailbox of their immediate neighbor, a famous actor, with a note. That didn’t work (despite them knowing each other).

But even if you don’t share a property line with a famous actor, don’t shove your script in their mailbox. It’s not how things are done.

But the Depp thing wasn’t a straight line. They initially passed but called back like 10 months later.

9) Okay, can you tell me about that? Did you find out the reasons why they initially passed? Was it one of those instances whereby the agent was making decisions for Depp and Depp never even knew about the submission?

Something like that happened with another project, but I didn’t find out what happened with Minamata until years later: The person at Depp’s company who had read it liked it and passed it up to his boss and they turned it down.

That first reader then later got a promotion and was offered to shepherd a project and he said, “I can’t stop thinking about that Minamata script.” And his boss said, “Well, if you feel so strongly about it, go for it.”

9) Also, I understand that you had Jeff Bridges attached for a while but that didn’t work out. What happened? Any cautionary advice you can give writers there?

Yeah, no one tells you this, but actors aren’t attracted to / “stick” to scripts – they are attracted and “stick” to directors who have a script or a project for them. They want to be directed. They want to work with the directors their peers have worked with (and maybe won their peers awards from working with those directors).

Look at Leonardo DiCaprio’s whole M.O. – for the last 20+ years he just exclusively works with A-LIST, top-shelf directors (Cameron, Eastwood, Allen, Scorsese, Nolan, Mendes, etc.). There’s no up-and-comers. He won’t “Bruce Willis” it with an up-and-comer like Tarantino like Bruce did with Pulp Fiction but he’ll sure work with him when he’s Tarantino.

On the “mailbox” script mentioned above, some big producers came aboard later and the first thing they did was go to directors they knew and to the reps of directors, not actors. The dream cast in our heads had to wait until a director was attached.

Scripts lead to producers which lead to directors which lead to actors which leads to studios / investors. All those elements are links in the chain.

So there were a few moments Bridges was interested, well, more like intrigued, but he wouldn’t budge if they wasn’t a director, even when there was a significant producer attached.

10) Okay, so did Depp only sign on when there was a director or did he come on first? (If he did sign on without a director, why do you think he went the opposite route of all these other actors you mention)?

The entire time the script was being developed at Infinitum Nil (Depp’s company), him starring was never discussed. And this was over a period of a year and half or more.

Now that I consider it, it may have been because there was no director attached.

And Depp himself did call director friends and associates and a cinematographer he had worked with for years to direct (him). He also hand wrote a note to another A-List actor / director to enroll him. Some responded to the material and Depp as Smith but had other professional and/or personal commitments.

When Andrew (Levitas) expressed an interest in directing it (I believe he was already attached as a producer), he and Depp met for a meeting that was supposed to be two hours which stretched into nine hours. I believe they talked about Smith, art, photography, visual touchstones, and their vision(s) for the material.

11) When did you find out that he was committing to star and what was that moment like?

I guess I found out when Andrew came aboard as a director — it was kind of stunning. Not only was I going to have a Johnny Depp movie — my first movie was going to be a Johnny Depp movie. I mean, I had grown up watching Edward Scissorhands, Gilbert Grape, Ed Wood, Blow, etc.

What was a particular thrill was, one of the producers (the original reader, Jason Forman — and later, another writer on it) sent me a photo of Depp in rough makeup at some point after that: a beard, a beret and holding a 35mm camera — Depp had had his makeup person do a test when there was a break in shooting something else.

I printed that out and tiled it so it was hanging over my bed, taped together in like 10 sheets of paper to remind myself it was real.

Still, I was always worried something would happen — like with financing or Depp’s schedule. You always hear about money falling through like with Dallas Buyers Club and other indie movies. I almost didn’t believe it was going to happen until I got paid and then like a couple weeks later was flying to Serbia, where we shot it.

12) Why do you think an actor such as Depp, who tends to be drawn to very interesting roles, liked this part so much? I guess I’m asking a bigger question here, which is: What kinds of characters are big actors interested in?

Smith was really in Depp’s wheelhouse – he was an artist to his core, rejected societal conventions, he had a fondness for drugs and alcohol (as did Hunter Thompson — who Depp played twice — and Jack Sparrow), and could be a real pain-in-the-ass and wasn’t afraid of making scenes but also had real heart. He was very larger-than-life.

But to your broader question: actors like playing interesting, complex, layered characters who say and do “cool” things. They love characters that are funny (Apatow characters), wicked smart (Imitation Game, The Social Network, Limitless, A Beautiful Mind, Good Will Hunting) – just memorable in some way.

13) Finally, is there some advice you can give from your personal experience that none of the film schools or screenwriting sites give on what it takes to get your script made into a movie? Does that “secret advice” exist?

There’s no secret – find unique ideas for movies (I just stopped working on 2 W.I.P.s when a recent collaborator / mentee of mine came up with a doozy and I pushed those two former ones hard to the side and I wrote the first act in 4 days), always be learning, find the HEART in your scripts / make me FEEL something, find and make friends in the same racket, read this blog, strive to be better – as good as the best, put yourself in a spot where you can be lucky and the odds can tilt slightly in your favor.

Minamata opens Friday in select theaters!

Today’s newsletter is a special one. I discuss the frustrations of a rejection-based industry as well as the two types of scripts you should be writing to have the best chance at penetrating the industry. There’s been some Star Wars news in the past month so you know I’ve got to talk about that. I’ve got a once-every-year super Black Friday consultation deal. I’m only giving three of those away so hurry up and read the newsletter to find out how to get one. One of my screenwriting tips involves considering a high-powered genre that I don’t think any screenwriters know about. We’ve got a Brit List sighting. And, finally, I review a top 5 Black List script written by a longtime Scriptshadow contributor! Definitely worth your time to check this out!

If you want to read my newsletter, you have to sign up. So if you’re not on the mailing list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER!” and I’ll send it to you.

p.s. For those of you who keep signing up but don’t receive the newsletter, try sending me another e-mail address. E-mailing programs are notoriously quirky and there may be several reasons why your e-mail address/server is rejecting the newsletter. One of which is your server is bad and needs to be spanked.

Genre: Science Fiction

Premise: Two decades after three strange abandoned alien city-ships crash into earth, a mysterious secondary enemy attacks our planet, forcing us to protect ourselves with the crashed vessels’ unique alien tech (robotech).

About: Sony has the rights to make a Robotech movie. At one point, Andy Muschietti (“It”) was tasked to direct. The project is currently stalled but it’s a property Sony likes a lot so it should get made at some point. This draft was written by S. Craig Zahler, who currently holds the number 3 slot on my Top 25 with his western, The Brigands of Rattleborge.

Writer: S. Craig Zahler (based on characters/concepts by Shoji Kawamori)

Details: 145 pages

I know we still have to finish up Comedy Showdown, but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t stoked for Sci-Fi Showdown!!! And when this script showed up in my Inbox, well, I couldn’t help myself.

Man, I loooooovvvvvvvved Robotech as a kid. I must have asked my parents a thousand times for the Robotech robot and got flat out denied each time. Instead they got me books. Wooopdeee doo. “Hey Baby Scriptshadow. I know you wanted that really cool robot that all of your friends would be jealous of but here’s a copy of Catcher in the Rye!”

Maybe this script will provide me with the joy I never received as a child.

One day, out of nowhere, three giant empty alien city-ships crash into our planet. One in Iceland, one in the Himalayas, and one off the coast of North Carolina. The ones in Iceland and the Himalayas explode on impact. But the one off the coast of North Carolina, while heavily damaged, manages to survive, resting out in the ocean.

Twenty years later, a global commission has sent a healthy group of individuals to live on the ship. Half of these people are mechanics, tasked with fixing everything up. The other half are military, there to study the unique vehicles in the city, which consist mostly of transformable airplane/robots called “Veritechs.”

Our main character is a mechanic named Hunter. He was recruited to come to the city by his military brother, Roy. The two just lost their father recently, and Roy is pissed that Hunter abandoned both of them. So let’s just say there’s a healthy dose of conflict in the family.

About 60 pages into the script, earth is attacked by an alien entity that’s been hiding out on the dark side of the moon. How long they’ve been there is anyone’s guess. But one thing is clear – they mean business. They start blowing up cities left and right. Hunter, who was once a pilot, ignores protocol and jumps into one of the Veritechs to fight off the aliens, which are known as Zentraedi.

The leaders of the planet do a little recon and discover the aliens’ plan. They’ve built giant thrusters into the moon so they can fly the moon away from earth, which will destroy all the tides. The oceans will wipe out all of life. Then, once humanity is gone, the Zentraedi will fly the moon back, re-establishing the tides, then take over earth for themselves.

What we eventually learn is that the Zentraedi were fighting some other mysterious alien race halfway across the galaxy. This race sent us these giant cities because they knew the Zentraedi were coming to wipe us out. Sort of like an intergalactic Amazon order. “Can you please send me one giant alien city with a couple of hundred transforming jet robots so I can protect my planet? Thank you. Wait, what are you talking about it’s not Prime. It’s not going to be here until next week??? Awww, come onnnn!”

What follows is a worldwide battle if there ever was one. We jump to the Arctic, we jump to Beijing, we jump to Taiwan. Hunter, not unlike Will Smith in Independence Day, becomes the best Veritech fighter. But will he be enough to take out an entire invading alien species? I guess we’ll find out!

I have a secret to share with you.

Even though I tell screenwriters never to write these large scale sci-fi screenplays (because they’re big and unwieldy and hard to manage), I LOVE the idea of large scale sci-fi. That’s what got me into this whole movie thing in the first place. Star Wars.

But I don’t think, since Star Wars, that I’ve read a single large scale sci-fi screenplay that’s worked.

The reasons are varied. The feature film format rewards tight timeframes and contained locations. Large scale sci-fi is the opposite of that. Then there’s the issue of creating a new universe out of whole cloth. In almost every iteration I’ve read of a screenwriter trying to do this, it ends up being a cheap copy of a movie that’s already been made.

I’d never tell you large scale sci-fi is impossible. But it’s whatever percentage it is that comes right before impossible.

However, if there’s any writer who’s got a shot at succeeding, it would be Zahler. I saw him create a universe out of whole cloth with The Brigands of Rattleborge. Granted that took place in the Old West. But it still exhibited the type of imagination required to tackle giant world-building.

Which is why I was so excited to read this script.

As is the the case with all of Zahler’s scripts, he takes his sweet time setting up the story. But unlike Brigands, which was clearly building towards a great sequence (the invasion during the storm), the buildup here is more expository in nature. Sure, seeing giant ship cities crash into earth is fun. But spending the next 50 pages setting up 20 different characters and the rules of the alien tech and what we’ve done since they’ve arrived got tiresome.

I supposed if you’re REALLY into the details of this mythology, it might be enough. But it reminded me a lot of Matrix Reloaded. Theoretically, going down into this underground city (Zion) and seeing how it operates should be interesting. But I, along with everyone else who watched that movie, was bored to death. We were ready to move forward a lot sooner than the directors were.

I get it. It’s hard to figure out with sci-fi what needs to be included and what should be relegated to backstory. But one of the most important ingredients in any screenplay is MOMENTUM. Once you lose that, it’s hard to get it back. And a lot of the momentum was lost in the section of this screenplay after the ship-cities crashed and before the aliens attacked.

Let’s talk for a second about what you can do to prevent something like this. Because, sometimes, you do need time to set your story up, especially if it’s a story like Robotech with all these moving parts.

Here are a couple tips. One, get rid of anything that you don’t absolutely need. Sure, spending several scenes setting up your Fifth Biggest Character helps us know that character better. But is knowing the 5th biggest character that well worth sacrificing momentum? You can usually cut out more than you think you can. So you should always err on the side of cutting.

Two, use ‘dramatic questions’ to keep “slow” sections interesting. A dramatic question is something you pose in a scene or a sequence of scenes that demands the reader keep reading to get an answer. The idea is, the reader’s more likely to stick around if he doesn’t yet have an answer to something.

And since not every scene in a movie can be juiced up with nuclear level GSU, a ‘dramatic question’ is a nice backup plan. In A Quiet Place 2, the characters get to safety early on in the screenplay when they reach a neighbor’s hideout. The script could’ve easily, then, gone into basic ‘information mode’ of “here’s how this guy lives. Here’s what all of the characters are now going to do moving forward.” But the sequence had this nice dramatic question of, “Who is this guy?” Is he good? Is he dangerous?” That added a little pep to a section that could’ve been stale.

That’s all dramatic questions are – they provide an extra layer of intrigue playing underneath the story for sections that are taking a GSU breather.

Robotech is okay. It’s one of those scripts that’s going to look so much better onscreen than it does on the page. Still, it was too information-heavy for me and needed more than those two modes – all-out exposition and all-out action. For that reason, it wasn’t quite worth the read.

Screenplay link: Robotech

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dramatic questions are only as effective as how interesting the question is. Let’s go back to that Quiet Place 2 example. The question of, is Cillian Murphy’s character dangerous(?) has major implications. If he’s a killer, they’re all in a lot of trouble. If the dramatic question had instead been, “Will they find food for the night?” I mean, sure, there’s some dramatic value to that question. But since they’re not going to starve if they miss one meal, the dramatic value is, overall, pretty low. So don’t just add dramatic questions. Make sure they’re compelling dramatic questions!

Lots of possibilities for you and Scriptshadow Productions today so make sure to read the whole post!

CONGRATS TO MAELSTROM!

A big congrats to Stephen Parker, writer of Maelstrom. He won this weekend’s High Concept Showdown. Here’s his logline: “When a freak storm hits a couples therapy retreat and turns all men in its path into predatory killers, a devoted wife and her new female allies must fight to save their lives, as well as their relationships.”

Right away, I noticed people talking about and debating the logline in the comments. That’s typically a good sign. Even if people don’t love your idea, the fact that they’re talking about it means it’s connecting with them in some way. It’s caught their interest. And that’s half the battle. It’s HARD to get people to pay attention to anything in a world with more entertainment options than ever before. So, good for Stephen. I’m excited to read and review his script this Friday.

OSCULUM INFAME HAS A NEW DRAFT!

I have a new draft of Osculum Infame. For those who don’t know, Osculum Inflame is one of the most disturbing yet incredible scripts I’ve ever read. It was so disturbing, in fact, that I worked with the writer on a new draft. That draft is now here. However, I need to warn you once again, that if you’re not into graphic disturbing material, there is no need to query me about this script. Here’s the logline: “A young woman is about to be hanged in the middle of nowhere. She’s already tiptoeing with the rope tightened around her neck, when her executioner dies unexpectedly. So now she’s literally hanging on for dear life.” ‘Buried’ meets ‘The Revenant’.

Here’s what I’m going to do. If you want to read the script and share your thoughts with me, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let me know that you can handle disturbing material. There is A CATCH to this. If I send you the script, I may call on you to read another script at a future date to give me notes on. If you’re cool with that arrangement, e-mail me!

And now, it’s time to announce the next Showdown. You’ve been whispering about it in the halls all weekend. Taking guesses. Making predictions. Well, now, I’m able to finally announce it. Our next showdown is…

COMEDY SHOWDOWN!!!

Holy Canoli, Carson. Comedy Showdown?? We haven’t focused on comedies for a long time on Scriptshadow. Where is this coming from? I’ll tell you EXACTLY where it’s coming from. EVERYBODY WANTS COMEDIES NOW.

The combination of a year-long pandemic and streamers loving the mid-budget comedy has resulted in a high demand for comedies everywhere you look. I have one producer who really wants family comedies (stuff in the vein of the upcoming “Yes Day” on Netflix). I have another producer who wants a “parents-centric” comedy. Parents have been locked up in their houses for a year with their kids. They’re itching to get out. A concept focused around them finally getting out and being free would be great. If you can nail one of those two scenarios, I can probably get your script sold quickly.

Some of my personal favorite comedies include: The Hangover, Bridesmaids, Happy Gilmore, Knocked Up, Meet The Parents, Borat, Step-Brothers, 40 Year Old Virgin, Tropic Thunder, Dude Where’s My Car, Superbad, School of Rock, What We Do In The Shadows, Office Space. The HOLY GRAIL COMEDY CONCEPT I’m personally looking for is the “next Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.” Something in the spirit of that movie but updated for 2021.

Here’s what I’m not looking for. I’m not looking for romantic comedies. I consider that its own genre. I’m not looking for dark comedy. I’m not looking for political comedies. I’m not looking for heavy satire. Even stuff like The Big Sick is too dramatic. I’m looking for the type of comedy that leaves you feeling good. That could still be R-rated comedy. Tropic Thunder was R-rated. But the idea here is to help people escape all the bullshit going on in the world for two hours. We want them to have fun.

In addition to holding a comedy showdown, I will also be helping you write it! But unlike before when I only gave you 2 weeks to write a script, this time you get 3 months. Plenty of time. Every Monday, I’m going to give you a list of things to do so that you stay on target. And because it’s comedy, I’ll be mixing in comedy-specific tips. Mostly, I’m going to help you structure out the three months so that you get the best script possible. Six weeks for the first draft. Four weeks for the rewrite. And two weeks for a polish.

And when do we start? RIGHT NOW!

Your week 1 goal is to come up with a concept. Your concept is EVERYTHING with a comedy. Unlike any other genre, people know immediately if a comedy script is going to work or not by reading the logline. If the logline doesn’t sound funny, there’s no point in opening the script. Never in the history of screenwriting has someone with an unfunny logline (or idea) written a funny screenplay. Which is why I’m giving you a full week to come up with one.

With comedy, you essentially have three avenues to pick from. You have your clever comedy premise (which usually involves irony), you have your common situation premise, and then you have your outrageous or ‘wacky’ premise.

The clever comedy premise has fallen out of favor recently but I believe it’s going to make a comeback. These concepts almost always involve irony. Happy Gilmore is about a hockey player who is forced to play golf. You have this big violent angry yelling sport contrasted against the ‘most polite’ sport in the world. That contrast creates irony which is what’s so funny about it. When you come up with a good ironic comedy premise, the script writes itself. Big, with Tom Hanks, was about a kid who turns into an adult and gets a VP job at a major toy company. That setup writes so many scenes for you.

Next up is the ‘common situation’ comedy which is probably the most popular of the options. This is when you take very common life experiences and build a comedy around them. Weddings. There’s a billion weddings. So somebody came up with Wedding Crashers. The stressful scenario of meeting your future in-laws (Meet the Parents). Getting someone pregnant (Knocked Up). These are a little tougher to write, in my opinion, because you have to use more imagination to come up with the plot. But, when done well, they’re obviously hilarious.

Finally, you have the outrageous comedies. Tropic Thunder is an example. The Hangover would squeeze in there as outrageous, I think. Zoolander, Ace Ventura, and Dumb and Dumber are a few more examples. You’ll notice these characters don’t exist in the same reality as you and I. They’re heightened versions of people. I tend to find that the wackier the characters are, the harder it is to keep the story believable. So you really have to be good at this type of comedy to write it.

Action comedies are also okay. But the concepts really have to be great because the movies cost so much more than a regular comedy.

In the end, I’m looking for CLEVER concepts. And your best tool to achieve that is irony. One of the reasons The 40 Year-Old Virgin came out of nowhere to be this monster hit was the irony in the concept. A 40 year-old man is “not supposed to be” a virgin. That’s what made it a fun idea. If you had written “The 25 Year-Old Virgin” nobody would’ve gone to the movie. A comedy titled, “Slutty Nun” is going to make a lot more money than a comedy titled, “The Polite Nun.” Irony is your best friend in comedy.

So, spend the next week coming up with as many funny ideas as you can. Take your top 5 and show them to five other people. Ask them if any of the ideas made them laugh. Whichever one gets the most laughs, that’s the one you’re going to write.

–I CAN’T STRESS THIS ENOUGH–

So many comedy screenwriters could’ve saved themselves YEARS of their life had they simply sent their comedy logline to five people to see if they thought it was funny. If none of those five people laughed, there is zero reason to write the script. One of the most inefficient things a writer can do is spend six months writing something only to THEN find out the idea isn’t funny.

BACK TO OUR REGULARLY SCHEDULED PROGRAM

That’s going to be a common theme throughout this process. In fact, if you’re on the fence about whether you can write a comedy script or not, team up with someone else here. Two minds are always funnier than one.

And with that begins… THE MARCH TO COMEDY SHOWDOWN!

What: Comedy Showdown

Genre: Comedy

When: Entries due Thursday, June 17, by 8 p.m. Pacific Time

How: Include title, genre, logline, why you think we should read it, and a PDF of your script.

Where: Send submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

If you already have something, you can send it now!!!