I love it when a movie like Smile, or one of its sequels, does well at the box office. In this case, Smile 2 took in 23 million dollars, which is 2 million more than the first film made.

Why do I like this? Because it’s something any aspiring writer on this site can achieve. I’m not saying it’s easy. But it IS achievable.

That’s because horror remains the NUMBER 1 avenue for an unknown writer to write a movie that not only gets sold, and not only gets made, but has the chance to become a hundreds of millions of dollars franchise. As Smile has already proven.

BUT.

You do need to understand how most horror projects get made in order to take advantage of this opportunity.

It’s tricky. So pay attention.

The majority of brand new horror films you see are created by writer-directors. From Lights Out to Get Out to It Follows to Smile. Usually, a short is created to show proof of concept or a new writer-director is in a position to make his first feature and goes with horror.

And you’ll notice a common thread with all these movies. They’re incredibly simple. Not just sort of simple. But INCREDIBLY simple. Lights Out is about a light switch. Get Out is a dude meeting his girlfriend’s parents. It Follows = a person follows you. Smile? Smile is a freaking smile! That’s it! The entire franchise is built on a single image.

So here’s the thing. I don’t think any of these movies would’ve worked as spec scripts. They’re too simplistic. And the key images (like an evil smile) wouldn’t shine bright enough on the page that someone would say, “I have to buy this.”

If you’re going to sell a horror spec, your concept and execution have to be a little more clever than the average screenplay. A Quiet Place is a good example. A world where you can’t make a sound or monsters kill you *is* still a simple premise. But note what the writers did with that. They created a nine months pregnant character who had no choice but to have a baby completely silently. That’s clever. And that’s why the script DID, unlike these other horror movies, sell as a spec.

So what do we call this practice then?

I think I’d like to call it SIMPLE + 1. Horror works great with a simple premise. That’s been proven over and over again. But “simple” means you have to direct it yourself. If you want to sell your horror script, you need that “+1” element. And, to me, the best +1 element is something more clever than the average bear. Either with the premise or the execution or both.

Sure, they’re older movies but I know for a fact The Sixth Sense would’ve sold today. As would The Others. As would Scream. Because they have that +1 element. The Sixth Sense has a prime hook: “I see dead people.” Not only that but an execution so great, it probably throws a +2 or a +3 into the mix. The Others was one of the better horror mysteries ever written (and also had a great final twist). And Scream was one of the best horror films ever at subverting the genre.

More recently on the spec side of things, you have horror films like 10 Cloverfield Lane, The Purge, Happy Death Day, The Menu, and, to a certain extent, Malignant (although I know there are extenuating circumstances with that spec sale). But I still think Malignant would’ve sold without the writer being in a relationship with James Wan.

So, if you want to sell sell sell a horror screenplay, make sure you are bringing a +1 element to the table. Otherwise, you could write the next “Smile” (“Sneeze” maybe?) and no one would take a chance on it.

As for the rest of the box office, I’m loving this little engine that could movie, The Wild Robot, crossing 100 million. It’s a bittersweet victory because I felt this movie had the best trailer of the year and since all animated movies make a billion dollars, it would as well. But then I learned this was a much smaller movie with smaller goals. Regardless, it’s got killer critic and audience scores, so much so that I almost bought it for 25 bucks on streaming the other day. Then I realized I’m not a crazy person. I could wait.

I’m still trying to work out We Live In Time’s path to production. Cancer films are about as fun to watch as cancer itself. But the truth is, actors do like these roles. And ever since Love Story’s surprise success in 1970, studios every once in a while take a gamble on one of these scripts, hoping they strike gold. I guess what I’m saying is, if you’re a writer who likes writing really depressing movies, there IS a path to success with cancer scripts. Actors will play these roles and studios will release these films. But come on. Which of these two movies would you rather see? This one?

Or this one…?

Saturday Night’s quick demise at the box office was as expected as leaves falling from trees in October. Jason Reitman continues to be one of the most toothless directors in the business. His films are so light and inoffensive, they might as well be a helium balloon at a 10 year old’s birthday party.

It’s not that I’m against feel-good movies. Give me a Wonka screening any day of the week. But even his feel-good movies are devoid of any effective drama or conflict. There are no teeth in a Reitman movie. Now, that being said, I do like the spec-y way he approached this movie, setting it in real-time on the first night of Saturday Night Live. But someone’s got to help Reitman read the room. He’s worse at picking concepts than Trajent Future.

Finally, props go out to Anora, the Sean Baker film that is so indie, it will stop collecting money as soon as it reaches 5 million at the box office. The film made 90 thousand bucks per theater this weekend. I like Sean Baker’s films because they live by the Scriptshadow creed of: KEEP IT SIMPLE. But also because he creates an energy in front of the camera that’s legitimately special. I planned to see this this weekend but a last minute schedule change prevented me from doing so. But I’ll watch it soon and review it! I expect it to be excellent and a major Oscar contender.

What’d you see this weekend? What’s your review?

What if I told you I could shave dozens of hours of work off your next screenplay? It’s simple. Stop putting so much time into description!

Not long ago, I was consulting on a screenplay. After I sent back the notes, which detailed some plot issues (the script lost a lot of its momentum in the second act) and some character issues (I didn’t feel like the main character was clear enough), I was surprised that the writer seemed unconcerned with either of these problems.

Instead, he was consumed with questions about his description. He asked me about a specific line describing a location on page 13, the introductory description of a secondary character not long after, and a couple of lines during a fight scene which he was concerned did not describe the fight in an exciting enough manner.

I’m not going to lie. I was frustrated. The script had way bigger issues than a random line on page 13 and whether a relatively unimportant character was described well. But then I remembered that when I first started writing, I was obsessive about this stuff as well. I would much rather spend a week on an already finished scene, trying to make sure every single word in the description was perfect, than tackle the glaring unlikability of my female love interest (haha, remember that terminology!)

There’s a reason for this. It’s because, when we start writing screenplays, we think that the most important thing is the WRITING. Which isn’t a surprise. “Screenwriting” has the word “writing” in it. Of course we’re going to think it’s about the writing.

It takes a while before we realize what screenwriting is really about. The storytelling. What is “storytelling” exactly? How does it differ from “writing?” Storytelling is the creative way in which we tell our story. From our plot choices to our character choices to our narrative choices. How we concoct that recipe has a massive effect on how the final dish tastes.

For example, when it comes to Strange Darling (major spoilers follow), another writer may have written that movie straight up. They may have told you, from the start, that the woman was the bad guy and the man was the good guy. To keep that information a secret for half the movie is a STORYTELLING CHOICE. And a strong one at that. It’s what makes the movie so enjoyable.

Think about that for a second. If that writer had spent 300 extra hours making sure every single descriptive line in the script was perfect BUT he told that story in a linear fashion (letting us know from the start that the woman was the bad guy), do you think the script would’ve been better or worse? Sure, it might have read cleaner and more descriptive on the page. But that pales in comparison to the feeling we got when that midpoint revelation arrived.

This is not to say that description isn’t important. Or that you shouldn’t pay attention to it. Description is kind of like sound in movies. We never think about sound unless it’s bad. Likewise, we don’t notice description unless it’s bad (clunky, lazy, or overtly generic).

Can sound actually improve a movie? Of course. In movies like The Zone of Interest, for example, the sounds of torture in the distance enhance the impact of the storytelling. But, in the end, we just want the sound to work, just like we want the description to work.

To that end, here are the three most important tips to remember when it comes to writing description in screenwriting.

Two lines per paragraph (or less) is best. Three lines if you’re writing a script that requires more description than usual.

These days, you really want your reader’s eyes moving down the page. So don’t write big paragraphs. Try to keep them short and to the point. “The woods were dotted with debris from the previous day’s vicious storm. Joe noticed many of the woodland animals up high in the trees, where they were safe, as if awaiting some official call from Mother Nature that going back to their daily routine was okay.” Do we really need the part about the animals? Couldn’t you get away with, “The woods were dotted with debris from the previous day’s vicious storm.” Ultimately, it’s up to you. But I find the second sentence to be unneeded.

Now, this changes if you’re writing the type of script that requires a lot of description. Ant-Man and the Wasp: Quantumania involves an entire universe that the reader is unfamiliar with. So you’re going to need to include a lot of description for that world. I might even say you can use some 4-line paragraphs in a script like that. But beware of writing too many of them as your description will start to look like a wall of text, which readers rebel against.

Prioritize description for the things that matter.

This is where a lot of newbie writers go astray. They treat description the same across the board. But that’s not the way to do it. Every element in your script has a “description priority level.” Wherever that element falls along that hierarchy determines how much description you want to use.

In the movie, “Wonka,” Willy Wonka is imprisoned at a “hotel” for most of the movie. This means that the hotel has a high description priority level. We’re going to see it again and again and again. So if your only description for a place like that is, “The hotel has an old-world charm, but the closer you look, the more decrepit it appears,” that’s simply not enough.

You’re going to need to tell us what the lobby looks like, how big the hotel is, if the rooms are big and cavernous or tight and claustrophobic. Is it clean or are there insects and rats scurrying about? Since we’re going to be in a lot of rooms here, it would be beneficial to lay out the geography of the hotel as well.

In comparison, if I remember correctly, there’s a scene in Wonka at a zoo. Because the zoo is one singular scene and because everybody has a good idea of what a zoo looks like, this description would have a very low priority level.

You describing it in some overly-detailed manner isn’t going to have a huge effect on how much the reader enjoys the scene. So it’s probably best to keep the description simple. “The sprawling urban zoo is complete with towering enclosures and winding paths, the air buzzing with distant roars and the chatter of children.” Boom, you’re done.

Now, let’s say you’re writing a movie like The Shining, where the entire movie takes place in that giant looming hotel. That’s a scenario where you want to – need to – go description crazy. Because the movie is built atop the atmosphere of this hotel. Every detail helps add to that atmosphere so it is okay to go hog-wild on your description.

Describe up to your writing ability level, but never above it.

One of the ways description stands out in the negative is when a writer tries to describe things in a manner above their writing level. Have you ever spoken to someone who throws SAT words into their sentences that aren’t used properly in an effort to sound smart? Same concept here.

“The golden-sand beach stood tall against the prospect of time, fighting a losing battle as every wave swooped at it like a thief in the night, taking one more coin from its pocket.”

Do you see the attempt to sound thoughtful and clever, when all the description does is give the reader a clunky not-so-clear picture of the beach? Luckily, description works best when it’s simple and clear. Which means you don’t have to be a wordsmith to write effective description.

“A quiet beach stretches along the coastline, golden sand meeting the gentle rush of waves.”

That’s 3rd grade English BUT IT WORKS. That’s the most important thing to remember when it comes to writing description. If it works, that’s all that matters.

Wrapping things up, I promise you that your story represents 95% of what the reader cares about. While strong description can help a script, particularly if it’s a highly visual concept, clarity and simplicity will pay higher dividends on the whole. Be visual but be CLEAR. Do that and you’ll be a-okay.

I’m still offering October screenplay and pilot consultation deals. $100 off my full rate. Plus an extra $50 off if it’s a horror or thriller related story. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and mention this post if you’re interested!

A rare spec script that makes it to the big screen!

Genre: Courtroom Thriller

Premise: When a man is brought onto the jury of a slam-dunk murder case where he realizes he is the murderer, he must decide whether to save himself by convicting an innocent man or to sway the jury to let the falsely accused defendant go free.

About: This is the big Clint Eastwood project coming out soon. It stars Nicholas Hoult as the titular character. The script was written all the way back in 2008. Talk about inspiration to keep hopes alive on old scripts you’ve written! Although I won’t know for sure until I see the movie, it’s likely that Eastwood used that 2008 draft, as he’s known for sticking with the first drafts of scripts. He likes the rawness of them and feels that they’re more truthful (the same reason why he goes with a lot of first takes as well).

Writer: Jonathan Abrams

Details: 104 pages

I will always ride or die with a spec script that makes it to the big screen. It’s rare. So it’s worthy of celebrating when it happens.

Why is it rare? Because you have to understand how Hollywood works. Hollywood has always been a risk-averse business but they’ve never been more risk-averse than right now. Therefore, the only time they feel comfortable with a project is when it’s been proven. Proof equates to PEOPLE SPENDING MONEY ON IT. That’s why yesterday’s Horrorstor got optioned. Because people had purchased the book.

A script? A naked script is the biggest gamble in the business. It hasn’t been proven on any level. Which is why the only time Hollywood takes interest in one of these stacks of paper is when someone successful says *I* like this script.

That’s not to say a script won’t sell. Case in point, this script caught Clint Eastwood’s interest and, hence, the studio said, “We’re in.” So you have to get your scripts in front of enough of these greenlightable people until one of them says yes. What’s the best way to get scripts in front of these people? Agents. They have relationships with all the talent and can therefore get scripts to them. How do you get a script in front of agents? The best way is through managers. Managers are more writer friendly and therefore easier to get scripts to. They have relationships with all the agents and will send your script to their favorites when they think it’s time. How do you get managers to read your scripts? Cold e-mail them. If you’re resourceful, it’s not hard to get most of their e-mails online. But you better come to them with a logline that has a hook. Or else it’s very likely that won’t bother requesting your script. These guys need to pay the bills. They’re not millionaires so it’s in their best interest to find the kind of concepts that sell. Keep that in mind the next time you’re thinking about sending your meditative road trip journey through Wyoming written in iambic pentameter.

Okay, with that out of the way, let’s talk about today’s script.

Justin Kemp, a normal 30-something dude with a wife and kid, has just been called in for Jury Duty. He’s not exactly thrilled about it but believes that it’s a civic duty and, therefore, when he shows up, he doesn’t try any of the sly tricks to get out of the gig. As a result, he’s chosen as one of the twelve jurors.

The case, it turns out, is about a guy, James Michael Sythe, who it is assumed murdered his girlfriend. The prosecution argues that Sythe, a former gang member with a temper, was so angry after his rich girlfriend broke up with him, that he bashed her over the head with a paper weight, took her body to a nearby road on a high cliff, and tossed it over.

But it’s when the lawyer mentions the date and the place that the incident happened that stops Justin cold. It was on November 6th of last year on a specific road. We get a quick flashback of Justin on that very road on that date last year. It was dark, storming. He was in his Land Rover. And he hit something. He screeches to a stop. Looks back. Doesn’t see anything. Or doesn’t want to. He then speeds off. This whole time, he told himself he hit a deer. But it turns out, he hit and killed a person.

Justin is, justifiably, rattled. But once he recovers, he has a life-altering decision to make. Does he send a man to prison who he knows didn’t commit the murder? And if not, how does he convince the other jury members, all of whom are 1000% sure this man did it, not to convict him, without drawing suspicion towards himself?

Justin decides he’s going to do the right thing and convince everyone that the defendant is innocent. But that strategy gets him in trouble almost immediately. The one jury member who wasn’t convinced the guy killed the girlfriend, a cop, privately starts looking into the case. He checks with his old friend, the coroner on the case, and finds out that the injury that killed her was more consistent with a car hitting her than a paperweight. Uh-oh.

Due to a mistake by that jury member, the prosecutor gets wind of this theory and starts looking into all of the cars that came in for auto work that time last year. After narrowing the field, she finds that there are a handful of cars that could’ve done it. And isn’t she surprised when one of them turns out to be Justin’s wife! Justin has no choice but to now let his wife in on the truth. But it may not matter. The walls keep closing in on Justin as they get closer and closer to a decision.

Today’s script comes from the school of “Find a new spin on your favorite movie.”

Or, it could even come from the school of, “Find a new spin on a famous movie that hasn’t had a new spin in a while.”

What’s that movie we’re talking about today? 12 Angry Men.

I’m actually surprised more scripts aren’t inspired by this premise due to it being tailor-made for tension, suspense, and fun revelations.

But, like I always say, every idea comes with its own set of challenges. Even the best ones. And this one comes with a couple.

For starters, don’t write one of these movies unless you are a) a lawyer or b) have an insane, obsessive, appetite for these legal stories. You cannot write one of these if you only have the idea but no knowledge of how legality in a courtroom works. I can promise you – PROMISE YOU – that your script will not be received well. You won’t be able to capture the authenticity and detail of a real court case.

Another thing about these court scripts is that THEY MUST BE CLEVER.

Court scenarios are built for surprises and revelations. One of the reasons the court movie fell out of favor was because TV could accomplish the same thing. Thousands of court shows were then produced and all of them were trying to out-clever each other with their plot developments. Therefore, if you’re writing a courtroom movie? You have to come up with a top top TOP level of cleverosity to justify it.

So, let’s talk about how Abrams did.

Did he pull this off?

I would say that he did a decent job. I definitely wanted to know what happened next and, one could argue, that’s all a script needs to be successful – the desire for the reader to turn the pages.

But I think he kind of wimped out when setting up the main character.

Justin didn’t know that he murdered someone until he got into the courtroom. While this allows the main character to be likable, which is, I’m sure, what motivated that choice, it steers the script away from the far more interesting version of Justin, whereby he killed someone, knew it, and is steering the jury towards a guilty verdict.

Believe me, I know that the darker version of Justin is a harder path to go down. Because in every step of the script’s development, you’re going to get pushback. People are going to tell you, “The main character isn’t likable. Nobody wants to root for a murderer. Making your main character a bad person is script suicide.” I get it!

But there’s no question whatsoever that Justin being the inadvertent murderer and trying to get this guy convicted is the more interesting storyline. And it’s doable! You can do things like make the defendant a really bad person outside of not murdering the woman, so we still root against him. And there are always things you can do to make your main character more likable. There are plenty of famous murderers we have rooted for throughout our moviegoing history. Heck, we all once rooted for a cannibal!!!

Despite this more friendly interpretation of the setup, the script is still pretty good. Abrams does a good job with the prosecutor, Faith, closing in on Justin, so it isn’t just the jury decision we’re looking forward to. We’re looking forward to whether Faith is going to expose him.

Definitely a fun spec script that’s worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is a great example of the power of choosing timeless concepts. When you choose a concept like Horrorstor, your script is dependent on how long Ikea stays within popular culture. But if you choose a concept about a courtroom murder case, you could have 10-20 years of that script being a viable potential purchase. This script was written 16 years ago but because of the timeless concept, it was still buyable after all that time.

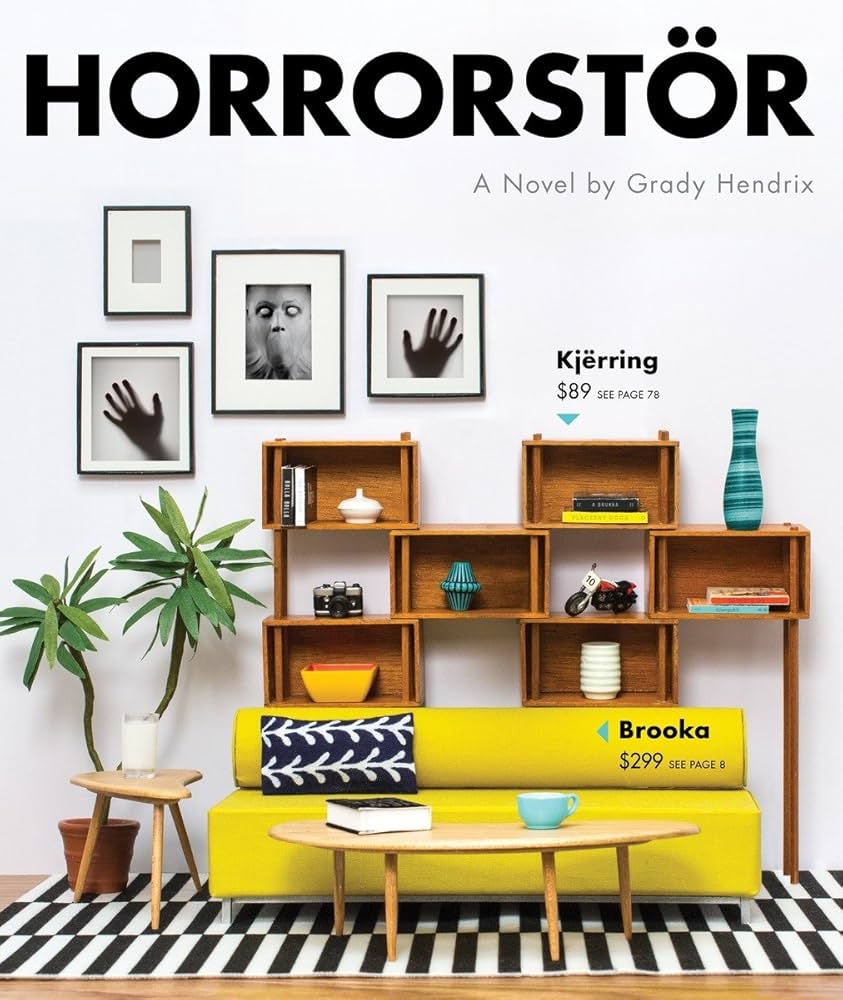

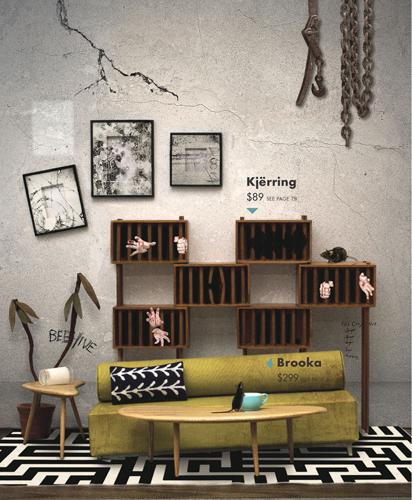

Genre: Horror

Premise: A group of workers at an Ikea-like store find themselves lost within its maze-like interior after a late-night seance goes wrong.

About: Horrorstor was published in 2013. New Republic Pictures optioned the book to turn it into a movie in 2020. Before that, it was conceived as a TV series, with screenwriting royalty Charlie Kaufman set to adapt. The heat off the Horrorstor sale led to writer Grady Hendrix’s latest novel,The Southern Book Clubs Guide to Slaying Vampires, selling to Amazon in a ten buyer bidding war.

Writer: Grady Hendrix

Details: about 250 pages

I had my eyes on this one ever since it sold.

It’s a genius idea. Placing a horror film in an Ikea store!? Story perfection.

Why?

Because I like fresh angles into old genres. I’d never seen this combo before. And it gets more clever the more you think about it. I remember when I used to go to Ikea (back when everybody was going) and thinking, “This place is kind of like Hell.” It’s this never-ending maze that sucks you in and forces you to buy a lot of things you don’t need.

I was curious to see what the author would do with it. Let’s find out.

24 year old Amy works at Orsk, an Ikea knock-off that somehow has even lower prices than the infamous Swedish furniture store. Amy has had a tough life. She grew up in a trailer. Her mother has had numerous boyfriends. Without higher education, she’s been stuck in a cycle of barely-above-minimum-wage jobs. Orsk is the culmination of that cycle.

But even though she hates her job, she needs it. Which is why she’s freaking out on this particular morning. Word on the street is that firings are coming. And Amy is the most fireable employee there. She shows up one minute before work and leaves the second the clock strikes 5. She is the epitome of a worker who only thinks about herself.

So when she’s called in to see her boss, Basil, she’s surprised to see Ruth Anne waiting outside his office. 42 year old Ruth Anne is the hardest worker there. She can’t possibly be getting fired as well? Turns out her instincts are correct. Company man Basil tells them he’s not firing them. He needs them for a special top secret job.

Someone is sneaking into the store after hours and smearing their feces on the furniture. He needs Amy and Ruth Anne to help him monitor the building that night. Amy agrees only because Basil promises to give her a transfer to another better Orsk store in the city. So away they go.

Amy and Ruth Anne think they find the culprits but it turns out to be co-workers Matt and Trinity, who have secretly been hooking up after hours. Tonight, Trinity is leading the two on a ghost hunt, complete with a running camera. Her dream is to get a real ghost on video so she can start her own ghost-hunting show (“Ghost Bomb”). Matt, meanwhile, is clearly going along with it to get laid.

Matt and Trinity join Amy and Ruth Anne, eventually finding the real culprit, a guy named Carl. Carl is homeless and has been sneaking in here at night to sleep. But Carl swears he’s not smearing any bodily functions on the furniture. Trinity, who’s pissed off that Carl isn’t a ghost, implores everyone to join her in a seance, since seance scenes always do well in these ghost hunting shows.

At first, the seance is fun, until Carl takes on the persona of someone named “Josiah.” Josiah informs all of them that they’re dead meat. And he’s very convincing, speaking in a different voice and everything. It’s enough to get them to stop the seance. But the damage has already been done. When they try to get back to the main showroom, they keep going in circles for some reason. That’s when they realize that Orsk is no longer a fun store. It’s a giant maze and there’s no way out.

Except that somehow, Amy does find a way out. She gets to her car in the parking lot and is ready to get the hell out of there. But something tugs at her. She’s been selfish her entire adult life. Does she really want to leave her co-workers here to die? Or should she go back into this panopticon and get them out of there?

Horrorstor is, basically, a screenplay. It’s written like one so it can be treated like one for the sake of today’s analysis.

I want to bring particular attention to how the story starts. A lot of writers know they need to start their screenplays with something happening in order to grab the reader. But they erroneously believe that “something happening” means something big, such as a car chase or someone getting murdered or an exciting flash-forward.

That’s not true.

With a little knowledge, you can use more restrained story mechanisms to “make things happen” early on and pull the reader in as a result.

For example, Amy shows up to work at Orsk. For the sake of argument, I want you to imagine you’re writing this movie. You’re bringing your main character to work in the morning. How are you going to write these opening scenes to pull the reader in?

I’ll tell you what bad writers will do. They’ll show the beginnings of the protagonist’s day. They’ll show them get to work. They’ll show them talking with their co-workers. They’ll show them prepping for opening. They’ll show them dealing with the first customers.

I can see how, in one’s head, that would make sense. You’re setting up the main character and the main location. So you are achieving something.

But, what you aren’t doing is giving the reader a reason to keep reading. What’s making me want to turn the page here? To see my main character at work? Why would that be interesting? Why would I want to see someone at work? I see people at work every day of my life. Why would you think that showing more people at work would capture my interest?

Here’s what author Grady Hendrix did instead. He zoomed in on the fact that firings are coming and our main character is, likely, first on the chopping block. Not only that. But he establishes that Amy *cannot* lose this job. She’s about to be kicked out of her place by her roommates for being late on her end of the rent again.

Do you see the difference in terms of storytelling here? This isn’t just someone showing up to work. This is someone trying to avoid getting fired. Now I have a reason to turn the page. I have to see if she’s going to get fired or not! Storytelling can be as simple as that. You put out a carrot. You stack some stakes on top of that carrot. And people will keep reading. As soon as you get to the carrot, introduce another carrot. And so on and so forth.

But Horrorstor runs into some problems once it moves into its horror storyline. I don’t like when story points emerge accidentally. I like them to feel planned. Carl the Homeless Guy shows up. Turns out he’s just a normal dude. This puts the plot on ice for a chapter. We’re not sure why we need to keep reading other than the author is still typing words.

And then Trinity says, “Let’s do a seance!” It sort of makes sense in that she needs footage for her ghost-hunting show. But it’s a lazy development that comes out of nowhere. And when Carl takes on this Josiah personality, it’s too convenient of a plot beat. Seconds ago Carl was a dead story thread. Now he just happens to channel this evil entity who will power the rest of the narrative?

To be clear, Josiah was set up beforehand. He’s the warden of an old prison back in the 1800s which used to reside on the land Orsk is built on. But it still felt entirely convenient that this homeless dude happens to channel this guy during a seance that someone came up with five minutes ago as a spur of the moment idea that seemed to spring from the fact that the story had lost its plot.

But then the story rebounds when it focuses on them getting lost in Orsk due to the fact that it was building on the clever idea that people get lost in Ikea all the time and the only way out is to go through every single entire room in the building to ensure that you purchase as many things as possible. It was reminiscent of the kind of social commentary you saw in George A. Romero’s, Dawn of the Dead, with the zombies crawling back into the malls so they could consume consume consume.

So whenever our heroes were trying to find their way out, only to find themselves deeper and deeper within the caverns of the Orsk maze, I liked the book.

I also liked what Hendrix did with Amy’s character. She’s established as this woman who only cares about herself and doesn’t subscribe to the “family” theme Orsk promotes, that everyone who works there should help each other. I always tell you guys that, late in your script, your main character should face a choice, preferably one that challenges her primary character flaw.

That’s what we get from Amy. She’s in the parking lot. She’s free and clear to go. But then she realizes that, if she leaves, these people may die. Does she stick with her selfish approach to life and save her own ass? Or does she help the others?

Why hasn’t this movie been made yet?

It’s a challenging sell! Terrifier 3 is doing well because of how unapologetically it leans into the horror genre. “Scary clown” is the logline. That’s all it needs to be. Setting a horror film in an environment like an Ikea doesn’t come anywhere close to the marketability of a scary clown. It’s a risk. True, it’s a risk that, if it pays off, it looks amazing. But it’s still a risk.

What sucks is that Ikea is no longer a pop culture store like it used to be. So any movie set in one is going to feel dated.

But, you never know. I still think it’s a fun idea.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Cerebral Horror is a great screenplay “feature” but it should never be the main attraction. The reason this sold is because of the cerebral nature of the concept. People in Hollywood love that stuff. But audiences don’t care about that as much, especially when it comes to the horror genre. Imagining Ikea as Hell is fun. But it’s not as scary as a crazy clown killing people. So make sure if you come up with a cerebral horror idea, it still has something genuinely scary in it.

We also take a mini-mish-mash-monday look at this weekend’s box office!

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A woman escapes a brutal attack during an impromptu late-night date and races into the countryside with her attacker hot in pursuit.

About: This is writer-director JT Mollner’s second feature film. Before that, he had written and directed four short films over five years. The film took over Fantastic Fest in 2023, landed a theatrical release with Miramax, and is just starting to come down to affordability on streaming. Oddly enough, actor Giovanni Ribisi is the cinematographer on the film.

Writer: JT Mollner

Details: 97 minutes

Joker 2??? There’s something otherworldly going on here. I don’t know what it is. I’ve never seen anything like it before. But a billion dollar movie whose sequel fell 80% at the box office is unprecedented. Not even The Marvels did that poorly.

And, the thing is, we all knew why The Marvels didn’t live up to expectations. The original Captain Marvel was sandwiched between two of the biggest movies of all time, Infinity War and Endgame. Its box office was guaranteed.

A major culprit in the failure of Joker 2 has to be the marketing. I was walking into the movie at the Westfield Mall here in Los Angeles and I bumped into someone I knew. She asked me what movie I was seeing and I said Joker 2. She was shocked. “Wait. That’s out??” She said. She had no idea. Not only that. She was a huge fan of the first film.

If your marketing isn’t able to let fans of the first movie know when your sequel is coming out, that’s a major failure on your part.

As for the movie that’s beating it this weekend, Terrifier 3, I don’t know whether to celebrate or castrate this film. It looks like it was put together by a couple of college buddies with 20 bucks and a clown costume they found in their parents’ basement. I’ve always encouraged the “make your movie any way possible” approach so, on the one hand, that’s awesome. But, as a movie, it looks less baked than the sweet potato I threw in the oven for 15 minutes last night. Terrifier 3’s success makes me want to conclude that scary clowns are box office magic but the tanking of Joker 2 says otherwise.

I will say that Todd Phillps’ refusal to screen his movie likely did it in. Whenever you’re making a complicated risk-taking movie like Joker 2, feedback is invaluable. He could’ve gotten important notes that told him what was and wasn’t working and recut it. But he said, nope, this is my vision for better or worse.

There’s a screenwriting lesson to take away from this. Always get feedback! If someone as successful as Todd Phillips can be wrong about creative choices, I got news for you: YOU CAN BE WRONG TOO. There’s nothing wrong with finding out what your script’s blind spots are.

Okay, let’s move on to Strange Darling.

Strange Darling is a perfect movie to review on Scriptshadow because it shows that it’s possible to get that coveted theatrical release despite having an indie-sized budget.

The script does several great things on the screenwriting side that all of us can learn from. Before I get into what those were, let’s summarize the plot, since I know a lot of you didn’t see the film. You should know that the movie is, in itself, a spoiler. So read at your own risk.

The script starts off with a crazed serial killer dude in a truck, chasing down a battered woman in a car on a two-lane road in the middle of nowhere. The guy finally screeches to a stop, gets up on the back of his truck, aims a rifle, and shoots out one of her tires, resulting in her crashing.

The crazed dude then chases her into the forest. She finds an odd older couple (they do Scott Baio puzzles together) living on a farm. They let her in. And we cut back to last night. We realize we’re on a date with the guy and the girl. They just met. She seems to be into some weird aggressive sex stuff. She asks if he’s down. And away they go to the motel.

Back to the present, but a little later on. The crazed guy is now in the house, gun out, hunting this woman down, looking in every nook and cranny of the home, shooting anything that looks even remotely suspicious. Cut back to the past, later in the date, and now the girl is asking the guy to do all sorts of violent sexual things to her. It’s getting weird. She’s getting suspicious.

Cut to the present again and now we see that the farm owner is dead. And this is when we realize we’ve been duped. The guy isn’t the bad dude. The girl is. She’s a serial killer. And when we cut back to the past, we see that he only barely survived her attack. She had to run and he’s been chasing her all day. This all culminates in a wild unexpected ending where you genuinely have no idea how things will conclude.

This was a really exciting movie. It has that 90s indie “can do” filmmaking spirit to it. I think they even shot it on film, giving it a weathered gritty look. The script is very clever in the way that it feels big (there’s a lot of chasing in this movie) but, in order to keep the budget lean, it stealthily inserts these long close-up centered dialogue scenes. It really is a perfect exercise in finding that balance.

Let’s talk more about that screenwriting because I think a lot of people continue to believe that screenwriting is 90% about dialogue. Dialogue is important, don’t get me wrong. I wrote an entire book on it. But the dialogue is the weakest part of this movie. Yet it didn’t matter. Because the storytelling was so strong.

So that’s your first lesson. Focus on writing a great story. Make sure it has a strong plot engine, that the characters are interesting, that the developments are exciting. Throw in a couple of twists to keep the reader off-balance. If you do that well, you don’t need to be a great dialogue writer. As this film proves.

The big screenwriting lesson to come out of this movie, though, is that you can elevate a basic story by playing with time. These are always the movies that tend to get screenwriters mentioned in the reviews.

Think about it. If this was just about a guy chasing a girl, the screenwriter gets zero credit. But because of the out-of-sequence nature of the script, you leave this movie thinking about the script. That puts you in a powerful place as a screenwriter since screenwriters usually get the blame when a movie is bad and never get the credit when it’s good.

The other big tip here is a bit controversial. So, if you’re easily triggered, step away. The note is: Take advantage of society’s expectations. Once society has a locked-in belief, you can control them with your storytelling. Strange Darling does an exceptional job at this.

Society, at the moment, is partial to the ‘toxic masculinity’ narrative. Therefore, if a violent event has occurred between a man and a woman, what are 99% of people going to assume? They’re going to assume that the violence is of the man’s doing. Writer-director JT Mollner knows you will assume that and uses that expectation against you.

When we realize that it’s actually the girl who is the serial killer, our entire world flips upside down. We did not think that was possible. It’s a great midpoint twist that not only supercharges the movie, but ensures you will not forget the movie anytime soon.

I always like to say that using an audience’s expectations against them does double-duty. It doesn’t just set up the great twist where you reveal things are the exact opposite of what they assumed. But it sets a storytelling precedent whereby the viewer can no longer assume what’s going to happen. Anything that unfolds after that revelatory moment is a mystery because once the reader knows you can do that to them, they know you can do it again. Indeed, the movie ends on a note we weren’t expecting.

If you’re missing those gritty indie movies from the 90s, this movie will be your jam, and bread, and butter, and maple syrup. It’s that good!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I always tell writers to think about marketing in regards to the script concepts they choose. But Mollner disagrees. Here is his take on the topic from The Hollywood Reporter: “I actually disagree. If I had been thinking about how to market this movie while I was writing it, I may not have written it. It’s so difficult as an artist to discipline yourself to sit down and write and complete a screenplay. I’m compelled to do it and I have to do it, but it never stops being a grind. The only way I’m able to get through that process is to have it be something that totally inspires me, artistically, or somebody hires me to adapt a novel. It then becomes fun because it’s a high level of work. But when writing something original, it’s got to really get me excited. I’ve got to love the idea, and it’s got to gestate in my brain and in my heart for a good period of time before I finally have to write it.”

I’m still offering October screenplay and pilot consultation deals. $100 off my full rate. Plus an extra $50 off if it’s a horror-related story. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested!