Search Results for: 10 tips from

Earlier this week, I broke down Do The Right Thing, with a focus on dialogue. I’m fascinated by dialogue as it continues to be one of the most elusive aspects of screenwriting. There are a small percentage of writers out there who are so gifted in this area that they don’t need any help. But chances are, you’re not one of them. And you’re never going to be. I’m sorry, but it’s the truth. People who were born with that gift are no different from basketball players with a 50 inch vertical. No matter how hard you work at it, you’re never going to have a 50 inch vertical.

But here’s the good news, just like there are a hundred NBA players who don’t have a 50 inch vertical, there are hundreds of screenwriters making a living who aren’t great at dialogue. Wanna know the secret to how they survive? They know how to put their characters in situations that create INTERESTING dialogue. Note the difference. “Great” dialogue is David Mamet. It’s creating something out of nothing like he did with Alec Baldwin’s monologue in Glengarry Glen Ross: “Cause the good news is — you’re fired. The bad news is you’ve got, all you got, just one week to regain your jobs, starting tonight. Starting with tonight’s sit. Oh, have I got your attention now? Good. ‘Cause we’re adding a little something to this month’s sales’ contest. As you all know, first prize is a Cadillac Eldorado. Anyone want to see second prize? Second prize’s a set of steak knives. Third prize is you’re fired. You get the picture? You’re laughing now? You got leads. Mitch and Murray paid good money. Get their names to sell them! You can’t close the leads you’re given, you can’t close shit, you ARE shit, hit the bricks pal and beat it ’cause you are going out!!!”

But you don’t need to be David Mamet to succeed. You just need to create dialogue that keeps us interested. And the best way to do that is to set your dialogue up to succeed. Give your characters a situation that will ALLOW them to say interesting things. Almost all of this happens long before your scenes are written. You do it, by and large, by creating characters that naturally interact with each other in dramatic ways. Below, you’ll find 10 approaches to scene-writing that, if done right, should improve your dialogue dramatically. 90% of your scenes (or more) should include one of the following set-ups.

HEAD-BUTTING

One of the most obvious ways to create interesting dialogue is through conflict – having your characters butt heads. How intensely they butt heads will depend on the characters, the story and the individual situation. The most obvious form of this is “arguing.” Characters let loose and rail against one another. Be careful with these scenes though. They typically only work after the pressure has been building up for a long time. If your characters argue right away (although there are exceptions to this) it will feel “on-the-nose” to the reader. And remember, full-on arguing isn’t the only “conflict” option. Sometimes a simple disagreement can be enough to power a scene.

TENSION

Tension is like conflict’s little cousin. It resides right underneath the surface. As such, it’s often a precursor to head-butting. Look at “The Heat,” with Sandra Bullock and Melissa McCarthy. Or Han Solo and Obi-Wan Kenobi in Star Wars. Or Columbus and Tallahassee in Zombieland. There’s tension between all these characters. Sometimes it bubbles up into full on head-butting, but usually it’s like an annoying little mosquito in a tent buzzing in the character’s ear. Needless to say, the pent-up frustration this tension causes always works its way into dialogue in interesting ways.

SEXUAL TENSION

One of the easiest ways to write scenes is to have some sort of sexual tension between your hero and the romantic interest. Sexual tension only works, though, until your characters seal the deal (with a kiss, or sleep together, depending on what type of story it is). Sexual tension can occur in a single scene, such as when Will Hunting tries to pick up Skylar at the bar in Good Will Hunting, or it can drive a multitude of scenes and even an entire movie, like it does in When Harry Met Sally.

SUSPENSE

Tease the reader with something they want, then don’t give it to’em right away. Here’s a scenario that shows the power of suspense. Let’s say our hero, Dan The Detective, shows up at a murder scene. Just before he walks in the house, he gets a call from his wife. She reminds him that he needs to pick up their son after school. She asks if everything’s okay. They discuss a few more things. He finally hangs up and goes inside. Boring right? Here’s how to use suspense. When Dan shows up, have a cop come up to him, face white, shaking his head, and tell Dan that what he’s about to see inside is unlike anything he’s seen in 30 years on the force. “You’re not ready for this,” he tells Dan. Dan, and us, start to go inside, but oh no, Dan’s wife calls! The two have the exact same conversation as before. This time, though, the dialogue feels more alive for some reason. Why? Because of our anticipation. Because we can’t wait to see what’s inside.

RESISTANCE

Resistance is when one character wants something and another character doesn’t want to give it up. One of the most famous examples of this happens in Raiders of the Lost Ark, when Indy goes to get the medallion from Marion. But guess what? She doesn’t want to give it up. In The Avengers, Black Widow tries to convince Bruce Banner to join the Avengers team. He doesn’t want to. In Fargo, Marge wants to get those license plate numbers from Jerry Lundergaard (who doesn’t want to give them to her because he’s secretly stolen the cars). If you want to double the power of Resistance in a scene, have both characters want something and have both sides resist. In the Alec Baldwin Glengarry Glen Ross scene mentioned above, Baldwin wants to give his damn speech. But nobody wants to listen. Also, everybody wants those golden Glengarry Glen Ross leads, but Baldwin doesn’t want to give them away. Resistance is a powerful way to keep dialogue interesting and should be used in the majority of your scenes.

AVOIDANCE

Avoidance is when characters don’t talk about things that need to be talked about. You’ll use Avoidance most often with characters who’ve known each other for awhile. Girlfriends, boyfriends, husbands, wives, family in general. As we all know, people in any relationship get to a point where they’d rather bury their problems than deal with them. When these people talk to each other, you can feel their words dripping with subtext. One need only sit at a family dinner to know how to write one of these scenes. There are usually many things that people are thinking that they’re not saying for one reason or another. Often, they’ll talk about anything else to fill the silence.

CHARACTER DRAMATIC IRONY

Dramatic Irony is a fancy way of saying “someone’s got a secret.” So all you’ve gotta do is write a scene with two characters, where one of the characters is keeping a secret from the other. In other words, almost every scene from Breaking Bad. Walter is keeping from his wife, his kid and his brother-in-law, that he’s a drug dealer. So whenever he has conversations with them, we’re drawn in. It can also be scene specific. In Inception, when Cobb approaches Robert Fischer (once he’s inside Robert’s mind), Cobb’s secret is that he’s trying place information inside Fischer’s mind. Dramatic Irony scenes tend to be the most interesting, however, when it’s the “bad guy” who has the secret. Because in these cases, we’re worried for our hero’s safety. So in Die Hard, when John McClane meets Hans Gruber up on the roof and Hans pretends to be a hostage, we know Gruber’s secret, and are terrified it’s going to result in our hero’s death.

STORY DRAMATIC IRONY

This second version of dramatic irony is the famous Hitchcock example of a bomb under the table. It occurs not when the characters keep secrets from each other, but when the movie keeps a secret from its characters. You’ll see this in horror movies a lot. Imagine a happy couple enjoying a hike through the forest. Chances are, their conversation is going to be pretty boring. But let’s say at the beginning of their hike, we cut to deep in the forest where a crazed maniac with an axe is watching them. When we cut back to them talking, it’s going to be a lot more interesting, isn’t it? We’re worried for them and want them to find out about the psychopath.

COMEDY

One of the ways to make a scene interesting is to make it funny. Have the characters talk about funny things. Seth Rogen and James Franco talking about joints in Pineapple Express. Or in a romantic comedy, when the characters first start hanging out together. This Honeymoon Period should contain a lot of funny dialogue. But beware of resting on comedy alone to sell a scene. If you’re just trying to make your characters say funny shit, we’ll feel the pointlessness of the scene and start to get restless. Often, comedy should be coupled with one of the other options I’ve listed. For example, a lot of the humor in The Hangover doesn’t come from Alan (Zach Galifianakis) and Stu (Ed Helms) just trying to say funny things. It comes from the fact that there’s so much tension between them, from them always butting heads. Also, it should go without saying that if your script is heavily dependent on comedy scenes, you need to be sharp, witty, clever, and funny. This may seem obvious, but I’ve read upwards of 200 amateur comedies where I didn’t laugh once.

PHILOSOPHY

These scenes involve characters talking about fascinating shit. The scenes’ strength rests on how compelling that shit is. Have you heard of something cool you’ve never heard anybody else discuss before? Have you thought of something crazy that nobody else has thought of? Use your characters to introduce these ideas to the world. Potential subjects include God, UFOS, death, life, conspiracies, existentialism, philosophy. These scenes should contain the kind of dialogue that if someone were sitting nearby in a coffee shop, they’d drop what they were doing to listen in. Richard Linklater has become famous for this kind of dialogue in his Before Sunrise movies, Slacker and Waking Life. Woody Allen incorporates it into his scripts as well. It should be noted, however, that this dialogue is really hard to pull off. Most people who think they have interesting thoughts about the world just rehash the same stuff we’ve heard in a hundred other movies (or on the internet). Sure, when it’s done right, we get Before Sunrise. But when it’s done badly, we get Scenic Route. What’s Scenic Route? Exactly.

EXPOSITION SCENES

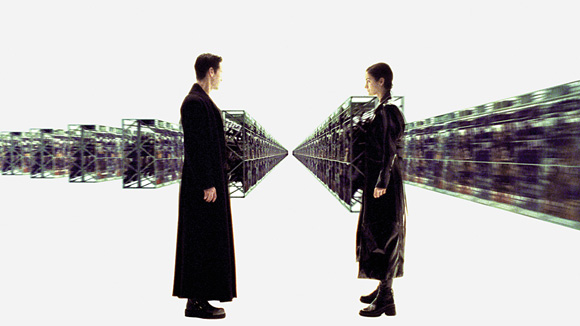

I’m including these scenes for one reason – because I don’t want you to write them. You should try to avoid, with all your might, writing scenes that are solely dedicated to exposition or backstory. Why? Because exposition and backstory are boring. Instead, break your exposition up into pieces and hide it inside all the other types of scenes I’ve mentioned. I admit this becomes harder to do for fantasy and sci-fi scripts though. With these films, there’s so much more information that needs to be given to the reader, that it’s tempting to write a scene that takes care of all of it. In these cases, just make sure that the exposition is really freaking interesting, like when we learn about the matrix in The Matrix. But I’m telling you, if you have more than even one of these scenes in your script, your reader’s already getting bored.

IN SUMMARY

When I read bad scripts, it’s often because there’s no conflict, no tension, no suspense, no dramatic irony. I’ve actually read hundreds of scripts that didn’t have a SINGLE scene with any of these things in them. You’d think that just by accident you’d write one of these scenes. Guys, these are the cornerstones of dramaturgy. You have to learn them. Now go through your current script. Make sure almost every scene is doing one of these things. And don’t be afraid to stack them. You can have scenes with sexual tension and dramatic irony. You can have scenes with tension and suspense. Get creative. Have fun. And most importantly, use these tools to elevate your dialogue.

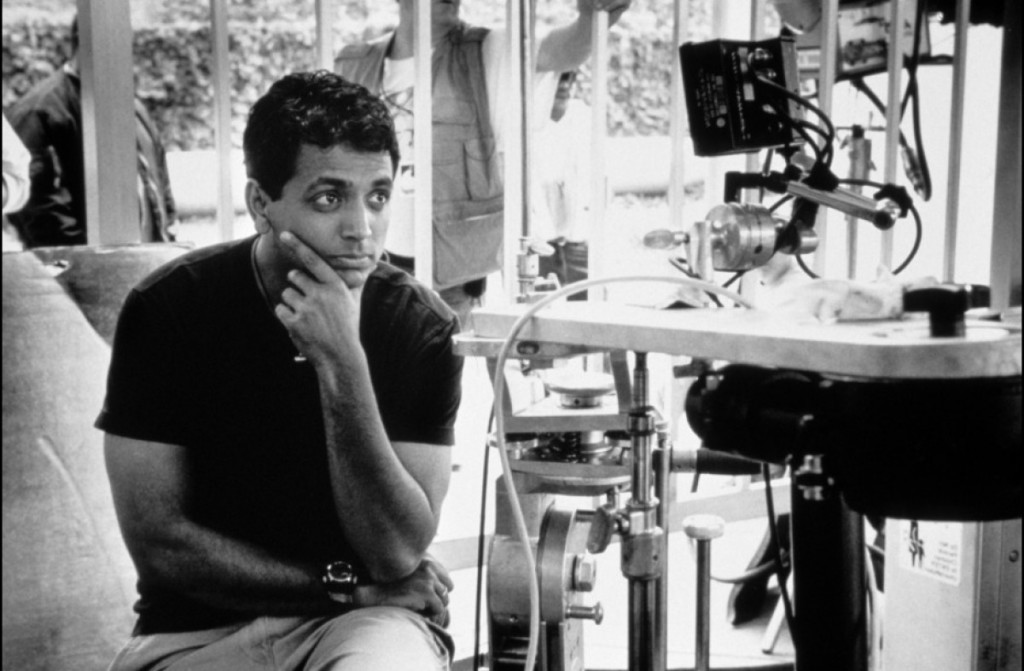

This man could SERIOUSLY benefit from a writing group. (“Ehhh, you could probably lose the werewolf made out of grass, Mr. Night.”)

This man could SERIOUSLY benefit from a writing group. (“Ehhh, you could probably lose the werewolf made out of grass, Mr. Night.”)

One of the more frustrating things about reading amateur scripts is seeing the same mistakes being made over and over again. These are simple mistakes that, had the writer had any sort of feedback community, they’d have nipped in the bud a long time ago. This is why writers can go 5-6 years without significant improvement. They have no idea what they’re doing wrong because they have no community to tell them that they’re doing anything wrong.

I also get a good e-mail a week from writers looking for writing partners. They ask me where the best place online to find a writing partner is, and their hearts sink when I tell them there isn’t one. At one point, I was going to create a Scriptshadow Social Network that highlighted and paired writers looking for partners, but it would’ve taken a year and too much money so I gave up on it.

Today, I’m going to solve both of these problems. You, my slug line slinging friends, are going to use the comments section to set up writers groups and find writing partners. The process for how you do this is up to you, but let me offer a few suggestions.

1) Tell us the genres you like to write in.

2) Tell us how many scripts you’ve written.

3) Tell us what level you’re at.

The third one is a little subjective, but it’s important, since no one likes to exchange work with people significantly below their level. So I’d suggest using my Screenwriting Rating System as a general scale. Keep in mind – and this is just in my experience – that women will tend to be honest with this scale, while men will rate themselves one or two levels higher than they are. C’mon guys, you know you do it.

Once you find someone you think could make a great partner or group member, contact them and trade a script with them. Lots of writers talk a big game, but there’s no way to know if their stuff is any good unless you read it. If you’re looking for a partner, you should really like the writing, since you’ll be working closely with the person. You can be a little more lenient if you’re looking for a group member, though. You don’t have to love someone’s work. You’re just looking for another set of eyes to give you feedback. As long as the person seems like they have a good grasp on the craft, they’ll probably be a good fit for your group.

Another reason I wanted to set this up was that it was a good opportunity to talk about feedback. Feedback is one of the most critical components to becoming a good writer. Not everyone has money for a professional consultation or is friends with a professional writer who’ll spend 8 hours breaking down your script and helping you. Agents and producers usually reject scripts with a form letter, so they’re not helpful when it comes to feedback. And while some contests offer notes, you don’t really know who’s giving those notes. It could be some 21 year old who doesn’t know the difference between irony and Iron Man.

Other writers reading your work, then, is your only real chance at getting critical feedback. However, feedback is not as simple as it sounds. It’s actually kind of complicated. There’s a little hidden language that goes on, and it changes from person to person. It’s important that you know how to speak this language, or you’ll have no idea if your script is actually good or not. So here are a few tips to keep in mind.

NOBODY’S MEAN

People are inherently nice (well, except for Grendl). They understand how much work you put into your script and how much you care, so if they don’t love it, they’re not going to anoint themselves your dream-crusher. They’ll look for any positives they can and focus on those. It’s actually hard to find someone who will be brutally honest and tell you your script sucks, so every bit of praise you hear during feedback should be taken with a grain of salt. How do you get honesty out of readers then? I’ll get into that in a bit.

FOCUS ON THE MEAN

For this reason, when you’re getting feedback, move past the compliments and focus on the negatives, even if the negatives weren’t that negative. Because the reality is, if someone says they thought your script was okay, it means they didn’t like it. If they say they didn’t like it, it means they thought it was awful. Nice people hide truths in between compliments. So it’s your job to read between the lines, find out what they didn’t like, and address those issues the best you can.

FAMILY AND FRIENDS

Family and friends are necessary to making us writers feel good. Writing is such a lonely journey, that there aren’t many opportunities to get praised. Giving your script to a family member or friend, someone you know is going to be supportive, is important for your self-confidence. But do not base any major script decisions on the feedback you got from family or friends. They are the least reliable in terms of if your script is any good.

EVERYBODY’S GOT AN ANGLE

One thing I’ve found over years of feedback is that everybody who gives feedback has an angle. And it’s your job to identify that angle and factor it into the feedback. For example, if a professor is giving you feedback, his angle is that he’s there to encourage you. So his notes are going to skew towards the positive. I’ve seen plenty of instances in “opposite sex script trading” (which sounds worse than it is) where one of the people secretly likes the other. Naturally, their feedback is going to be really positive in the hopes that you’ll like them. Even past history can influence script feedback. If you give a script to someone and they rip it apart, which sends you into a spiral of despair and lots of drinking, well, what do you think is going to happen when you give that person your next script? They’re not going to want to ruin your life again, so they’ll be a lot nicer. It’s your job to sniff out what the angle is of the person giving you feedback, and factor that in.

FIND THE MEANIES

We’re writers. Which means we’re insecure. We want praise so badly that we’ll do anything to get it, including deluding ourselves. We’ll seek out that guy or girl who has a crush on us to read our script, because we know they’re going to tell us everything we write is great. But if you really want to improve with your writing, you want to seek out those people who are mean (or, at the very least, brutally honest). The people who you know are going to tell you when something sucks. As long as they’re willing to tell you WHY they thought it sucked, so you can learn from their feedback, these people are invaluable. Because the truth-sayers are the only ones who are going to improve your script. When I give notes, the writers I like the best are the ones who say, “Be brutal.” Because they know that sugar-coating problems isn’t going to solve anything. Don’t look for Paula Addul. Find your Simon Cowell.

ASK ASK ASK

The best way to get true feedback is, after someone’s given you their thoughts on your script, ask specific questions. I’ve found that while people are really nice in their prepared post-read statement to you, that filter comes off once you start asking questions. For example, they may have casually mentioned that the characters didn’t pop off the page, making it seem like it was a minor problem. But when you ask them specifically about your hero, Jack, they get snarky. “I don’t know. He just seemed like an asshole.” Listen not only to what they’re saying, but HOW they’re saying it. Do they seem annoyed? Pissed? These are important emotions to track because they’re not the emotions you were hoping for. The more you can sniff out these problem areas through questioning, the better off your script is going to be.

HONEST FEEDBACK

The best way to get HONEST feedback from fellow writers is through a long-term relationship with them. The more scripts you trade with someone, the more you begin to trust each other, the more honest the feedback becomes. Just like any relationship, comfortability sets in, and you’re less worried about hurting each other, since you know that you’re both after the same thing, writing a better script. Let’s start that right now. Use the comments to find that group of people (or partner) who are going to help guide your writing through your amateur, as well as your professional, career. Good luck!

Should you be aspiring to write the next Cloud Atlas?

Should you be aspiring to write the next Cloud Atlas?

Today I want to pose a question to you that’s had me stumped for awhile.

What is the difference between BAD non-traditional writing and GOOD non-traditional writing?

I’m asking this question because I meet so many writers who insist on defying convention. I read their scripts and I say, “I don’t see a focused story here. I don’t see you setting up your characters correctly. I don’t see your story starting soon enough. I don’t see you adding conflict or suspense or any of the things that traditionally keep a reader interested.” And their response to me is always, “Well I don’t want to do it like that. That’s how Hollywood does it and I don’t like Hollywood movies. I want to do it differently.”

My gut reaction is to groan, but then I realize that they have a point. There isn’t just “one way” to do something. There are lots of ways. And if I tell these writers, “No, don’t do it that way,” aren’t I stifling their creativity? Aren’t I potentially preventing a new voice from emerging? If I was Captain of Hollywood, True Detective would’ve never been made. Yet there are a lot of people who love True Detective, and that’s definitely a show that “does it differently.”

Here’s the problem though. 99% of the time I let these writers roam free, they come back with a hodge-podge of ideas, sequences, and characters in search of a script. It’s like walking into a Category 5 Screenplay Storm. Anyone who’s been tasked with reading amateur scripts where the writers ignore all storytelling convention knows what I’m talking about.

Yet these writers continue to drum up compelling arguments to defend their approach. They say, “Well I don’t want to write Transformers, or Grown-Ups, or Identity Thief, or Olympus Has Fallen. Those scripts follow all the rules and they suck.” Hmm, I think. Can’t argue with that. And yet I can’t seem to convey to them that even Hollywood’s vanilla is better than their chocolate without getting a funny look or a black eye.

Maybe we can solve this by moving away from the amateur world and into the professional one. Because in this venue, writers are having the same battle. They all want to write something challenging and unique, a convention-defying opus that will win them an Oscar. All else being equal, no one wants to write Battleship. And they seem to have hard-core cinemagoers on their side. You need look no further than the Scriptshadow comment thread to see Grendl preaching this every day – break away from convention, ignore the rules, create something original!

But let me offer you the flip side of this argument. It’s only two words long.

Cloud Atlas

Here’s a book that was adapted by and then directed by the Wachowskis (and Tom Tykwer), three of the more visionary directors in Hollywood. The result was one of the most beautiful movies of the last decade. And one of the most unfocused unsatisfying stories of the year. I’m not going to say the film didn’t have fans. But by and large, it was a failure, making only 30 million domestic. A documentary about chimpanzees made more money that year.

I bring the film up because this is the kind of thing you’re advocating when you say, “Fuck convention and write whatever you want.” You have three of the stronger talents in the business writing six narratives spanning six different time periods, with no clear connection. Set one of those time periods a thousand years in the future. Have the main character followed around by a homeless looking Leprechaun creature who spouts out indecipherable ramblings. I mean come on! There isn’t a single audience member who’s going to respond to that. It’s too weird!

And I can hear you from here. You’re saying, “Well I’d rather Hollywood produce ten failures like Cloud Atlases than one “hit” Iron Man 3.” No you wouldn’t. You wouldn’t. I dare you to sit down and try and watch Cloud Atlas’s three hour running time and not start checking your e-mail by the halfway point. I thought Iron Man 3 was pretty bad. But at least it was trying to entertain me.

My lack of enjoyment not-withstanding, the point is, two popular writers were given free rein to go crazy with a huge budget and created a piece of doo-doo. Which begs the question, is this what we want all the time? Julie Delpy written movies? Shane Carruth written movies? Another “Somewhere” from Sophia Coppola? Steve Soderbergh busting out films like “Bubble” every year?

It sounds fun in theory. Yeah! Give those guys gobs of money and let them do whatever they want. But what are the actual consequences? The consequences are film geeks getting to masturbate online about 10 minute tracking shots. But that’s where the benefits end. There would be no movie business because attendance would be down 90%. And the thing is, what you’re asking for is already here! These movies have already happened. You’ve just never heard of them because they were so bad.

Does a movie that promises to aggressively subvert the romantic comedy genre sound intriguing? Sure. But watch “I Give It A Year” and tell me you don’t want to kill yourself by the end of the first act. Diablo Cody won an Oscar. Let’s let her go wild on the page and see what happens. It happened, with a movie called “Paradise,” which I’m pretty sure is still waiting for its first customer. Francis Ford Coppola was given free rein on his last film. What did he come up with? Twixt. I’m guessing you didn’t rush over to Fandango to find the opening day showtimes for that one.

Now you may be saying, “Yeah, but I don’t like the sound of any of those movies, Carson. So of course I’m not going to see them.” That’s the problem. Millions of other people feel the same way. And if no one’s going to see these “fuck convention – I’ll write what I want” movies, then there won’t be a movie industry anymore.

On the flip side, there are definitely screenplays that have defied convention and turned out great. Pulp Fiction, Slumdog Millionaire, American Beauty. More recently, some might say American Hustle and Her. Which is why answering this question is so difficult. What makes one unconventional script good and another terrible?

I’ll give you an example from both sides. What makes the intense dramatic unconventional Short Term 12 good while the equally intense dramatic unconventional Labor Day is terrible? I suppose we can break down each script point by point, but I’m looking at the bigger picture. How do writers not bound by rules keep away from the bad and write something good? Do they just follow their heart? Should writing contain no form whatsoever other than the stream-of-consciousness rolling off the writer’s fingertips? I mean we can’t really be advocating this, right? There’s got to be a plan.

Ah-haaaaa. I believe that may be the clue we’ve been looking for.

If we’re going to do something as radical as defy convention, it only makes sense that we have a plan. Now that I think about it, the successful “unconventional” screenwriters I’ve spoken with always knew why they did what they did. They understood their unorthodox choices and made them for a reason. The people whose unconventional scripts aren’t so good are those who can’t answer any questions about their choices. They seem tripped up when you ask them even the simplest question, like “why did you choose this plot point here?” or “why did Character A do that?” They never had a plan, which is why their scripts tend to feel so aimless and frustrating.

So what I’d say to everyone planning on writing that next great unconventional screenplay, learn everything you can about this craft and then have a plan when you write. It doesn’t have to be everybody else’s plan. It just has to be yours. And know why you’re doing shit. The more control you have over your choices, the more logical your script is going to be, and the easier it’s going to be for your reader to digest. If you think that advice is for wimps and you want to fly by the seat of your pants, that’s fine. But don’t be surprised if you leave a lot of confused readers in your wake.

What about you guys? What do you think the key is to writing an unconventional screenplay?

Inception’s first act is pretty awesome.

Inception’s first act is pretty awesome.

It surprises me that people have trouble with the first act because it’s easily the most self-explanatory act there is. Introduce your hero, then your concept, then send your hero out on his/her journey. But I suppose I’m speaking as someone who’s dissected a lot of first acts. And actually, when I really start thinking about it, it does get tricky in places. The most challenging part is probably packing a ton of information into such a small space. So that’s something I’ll be addressing. Also, I’ve decided to include my second and third act articles afterwards so that this can act as a template for your entire script. Hopefully, this gives you something to focus on the next time you bust open Final Draft. Let’s begin!

INTRODUCE YOUR HERO (page 1)

Preferably, the first scene will introduce your hero. This is a very important scene because beyond just introducing your hero, you’re introducing yourself as a writer. A reader will be making quick judgments about you on everything from if you know how to write, if you know how to craft a scene, and what level you’re at as a screenwriter. So of all the scenes in your script, this is the one that you’ll probably want to spend the most time on. It’s also extremely important to DEFINE your hero with this scene. Whatever the biggest strength and/or weakness of your hero, try to construct a scene that shows us that. Finally, try to convey who your hero is THROUGH THEIR ACTIONS (as opposed to telling us). If your hero is afraid to take initiative, give them the option in the scene to take initiative, then show them failing to do so. A great opening scene that shows all of these things is the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark.

SET UP YOUR HERO’S WORLD (pages 3- 15)

The next few scenes will consist of showing us your hero’s world. This might show him/her at work, with friends, with family, going about their daily life. This is also the section where you set up most of the key characters in the script. In addition to setting up their world, you want to hit on the fact that something’s missing in their life, something the hero might not even be aware of. Maybe they’re missing a companion (Lars and the Real Girl). Maybe they’re putting work over family (George Clooney in Up in the Air). Maybe they’re allowing others to push them around (American Beauty). It’s important NOT TO REPEAT scenes in this section. Keep it between 2-5 scenes because between pages 12-15, you’re going to want to introduce the inciting incident.

INCITING INCIDENT (pages 12-15)

Introducing the inciting incident is just a fancy way of saying, “Introducing a problem that rocks your protagonist’s world.” This problem makes its way into your hero’s life, forcing them to act. Maybe their plane crashes (The Grey), they get someone pregnant (Knocked Up), or their daughter gets kidnapped (Taken). Now your hero is forced to make a decision. Do they act or not? — It should be noted that sometimes the inciting incident will arrive immediately, as in, on the very first page. For example, if a character wakes up with amnesia (Saw, The Bourne Identity) or something traumatic happens in the opening scene (Garden State – his father dies), the hero is encountering their inciting incident (their problem) immediately.

HELL NO, I AIN’T GOIN (aka “Refusal of the Call”) (roughly pages 16-25)

The “Hell No I ain’t goin” section occurs right after the inciting incident and basically amounts to your character saying (you guessed it), “I’m not goin anywhere.” The reason you see this in a lot of scripts is because it’s a very human response. Humans HATE change. They hate facing their fears. The problem that arises from the inciting incident is usually a manifestation of their deepest fear. So of course they’re going to reject it. Neo says no to scaling a building for Morpheus and gives in to the baddies instead. This sequence can last one or several scenes. It’ll show your hero trying to go back to what they know.

OFF TO THE JOURNEY (page 25)

When your character decides to go off on their journey (and hence into the second act), it’s usually because they realize this problem isn’t going away unless they deal with it. So in order to erase this eternal snowfall, Anna from Frozen must go off, find her sister and ask her to end it. This is where the big “G” in “GSU” comes from. As your hero steps into that second act, it begins the pursuit of their goal, which is to solve the problem.

GRAB US IMMEDIATELY

Now that you know the basic structure, there’s a few other things you want to focus on in the first act. The first of those things? Don’t fuck around! Readers are impatient as hell, expecting you to be bad writer (since you’re an amateur) and judging you immediately. So try and lure them in with a kick-ass scene right away and don’t let them off the hook (each successive scene should be equally as page-turning). This doesn’t mean start with an action scene (although you can). It could mean a clever reversal scene or an unexpected twist in the middle of the scene. Pose a mystery. A murder. Show us something that’s impossible (people jumping across roofs – The Matrix). Use your head and just make us want to keep turning the pages even if our fire alarm is going off in the other room. Achieving this tall order WHILE doing all the other shit I listed above (set up your hero and his flaw), is what makes writing so tricky.

MAKE IT MOVE

It’s important that the first act move. Bad writers like to DRILL things into the reader’s head over and over and over again. For example, if they want to show how lonely their hero is, they’ll show like FIVE SCENES of them being lonely. And guess what us readers are doing? We’re already skimming. Typically, a reader picks things up quickly if you display/convey information properly. Show that your hero is bad with women in the first scene, we’ll know they’re bad with women. There are some things you want to repeat in a script (a character’s flaw, for example) but you want to slip that into scenes that are entertaining and necessary for the story, not carve out entire scenes that are ONLY reiterating something we already know. This is one of the BIGGEST tells for an amateur writer, so avoid it at all costs!

ENTERTAIN US WHILE SETTING US UP

You’re setting up a lot of stuff in your first act. You’re setting up your main character’s everyday life, their flaws, the love interest (possibly), secondary characters, the inciting incident, setups for later payoffs. For that reason, a first act can quickly turn into an information dump. That’s fine for a first draft. But as you rewrite, you’ll want to smooth all this information over, hide it even, and focus on ENTERTAINING US. Nobody’s going to pat you on your back for doing everything I’ve listed above. That stuff is EXPECTED. They’re only going to pat you on the back if your first act is entertaining. Think of it like this. Nobody wants to know how a roller coaster works. They just want to ride on it.

EVERY SCRIPT IS UNIQUE

One of the hardest things about writing is that every story presents unique challenges that force you to improvise. Nobody’s going to be able to follow the formula I laid out to a “T.” You’re going to have to adjust, improvise, invent. That shouldn’t be scary. You’re artists. That’s what you do. Just to give you a few examples, Luke Skywalker is not introduced in the beginning of Star Wars. Marty McFly doesn’t choose to go on his adventure. He’s thrust into it unexpectedly (when his car jumps back to the past). Some films, like Crash, have multiple characters that need to be set up. This requires you to set up a dozen little mini-stories (for each character) as opposed to one big one. Some scripts start with a teaser (Jurassic Park) or a preamble (Inception). The point is, don’t pigeonhole yourself into the above unless you have a very straightforward plot (like Taken, Rocky, or Gravity). Otherwise, be adaptable. Understand where your story is resisting structure, and be open to trying something different.

IN SUMMARY

That’s probably the scariest thing about writing, is tackling the unknown. So what do you do if you come upon these unique challenges? What do you do with your first act, for example, if the inciting incident happens right away, as it does in The Bourne Identity? Do you still break into the second act on page 25? Well, I know the answer to that question as well as some other tricky scenarios, but they’d require their own article (short answer – you break into the second act a little earlier, around page 20). What I’ll say is, this is one of the big things that separates the pros from the amateurs. The pro, because he’s written a lot more, has encountered more problematic scenarios and had more experience trying to solve them. The only way to catch up to them is to keep writing a lot (not just one script, but many, since each script creates its own set of challenges) and figure out these answers for yourselves. The good news is, with this article, you have a template to start from. And remember, when all else fails, storytelling boils down to one simple coda: A hero encounters a problem and must find a solution. That’s true for a story. It’s true for individual characters. It’s true for subplots. It’s true for individual scenes. If you follow that layout, you should do fine. And if you want to get into more detail about this stuff, check out my book, which is embarrassingly cheap at just $4.99 on Amazon! ☺

THE SECOND ACT!

Character Development

One of the reasons the first act tends to be easy is because it’s clear what you have to set up. If your movie is about finding the Ark, then you set up who your main character is, what the Ark is, and why he wants to get it. The second act isn’t as clear. I mean sure, you know your hero has to go off in pursuit of his goal, but that can get boring if that’s the ONLY thing he’s doing. Enter character development, which really boils down to one thing: your hero having a flaw and having that flaw get in the way of him achieving his goal. This is actually one of the more enjoyable aspects of writing. Because whatever specific goal you’ve given your protag, you simply give them a flaw that makes achieving that goal really hard. In The Matrix, Neo’s goal is to find out if he’s “The One.” The problem is, he doesn’t believe in himself (his flaw). So there are numerous times throughout the script where that doubt is tested (jumping between buildings, fighting Morpheus, fighting Agent Smith in the subway). Sometimes your character will be victorious against their flaw, more often they’ll fail, but the choices they make and their actions in relation to this flaw are what begin to shape (or “develop”) that character in the reader’s eyes. You can develop your character in other ways (via backstory or everyday choices and actions), but developing them in relation to their flaw is usually the most compelling part for a reader to read.

Relationship Development

This one doesn’t get talked about as much but it’s just as important as character development. In fact, the two often go hand in hand. But it needs its own section because, really, when you get into the second act, it’s about your characters interacting with one another. You can cram all the plot you want into your second act and it won’t work unless we’re invested in your characters, and typically the only way we’re going to be invested in your characters is if there’s something unresolved between them that we want resolved. Take last year’s highest grossing film, The Hunger Games. Katniss has unresolved relationships with both Peeta (are they friends? Are they more?) and Gale (her guy back home – will she ever be able to be with him?). We keep reading/watching through that second act because we want to know what’s going to happen in those relationships. If, by contrast, a relationship has no unknowns, nothing to resolve, why would we care about it? This is why relationship development is so important. Each relationship is like an unresolved mini-story that we want to get to the end of.

Secondary Character Exploration

With your second act being so big, it allows you to spend a little extra time on characters besides your hero. Oftentimes, this is by necessity. A certain character may not even be introduced until the second act, so you have no choice but to explore them there. Take the current film that’s storming the box office right now, Frozen. In it, the love interest, Kristoff, isn’t introduced until Anna has gone off on her journey. Therefore, we need to spend some time getting to know the guy, which includes getting to know what his job is, along with who his friends and family are (the trolls). Much like you’ll explore your primary character’s flaw, you can explore your secondary characters’ flaws as well, just not as extensively, since you don’t want them to overshadow your main character.

Conflict

The second act is nicknamed the “Conflict Act” so this one’s especially important. Essentially, you’re looking to create conflict in as many scenarios as possible. If you’re writing a haunted house script and a character walks into a room, is there a strange noise coming from somewhere in that room that our character must look into? That’s conflict. If you’re writing a war film and your hero wants to go on a mission to save his buddy, but the general tells him he can’t spare any men and won’t help him, that’s conflict. If your hero is trying to win the Hunger Games, are there two-dozen people trying to stop her? That’s conflict. If your hero is trying to get her life back together (Blue Jasmine) does she have to shack up with a sister who she screwed over earlier in life? That’s conflict. Here’s the thing, one of the most boring types of scripts to read are those where everything is REALLY EASY for the protagonist. They just waltz through the second act barely encountering conflict. The second act should be the opposite of that. You should be packing in conflict every chance you get.

Obstacles

Obstacles are a specific form of conflict and one of your best friends in the second act because they’re an easy way to both infuse conflict, as well as change up the story a little. The thing with the second act is that you never want your reader/audience getting too comfortable. If we go along for too long and nothing unexpected happens, we get bored. So you use obstacles to throw off your characters AND your audience. It should also be noted that you can’t create obstacles if your protagonist ISN’T PURSUING A GOAL. How do you place something in the way of your protagonist if they’re not trying to achieve something? You should mix up obstacles. Some should be big, some should be small. The best obstacles throw your protagonists’ plans into disarray and have the audience going, “Oh shit! What are they going to do now???” Star Wars is famous for one of these obstacles. Our heroes’ goal is to get the Death Star plans to Alderaan. But when they get to the planet, it’s been blown up by the Death Star! Talk about an obstacle. NOW WHAT DO THEY DO??

Push-Pull

There should always be some push-pull in your second act. What I mean by that is your characters should be both MAKING THINGS HAPPEN (push) and HAVING THINGS HAPPEN TO THEM (pull). If you only go one way or the other, your story starts to feel predictable. Which is a recipe for boredom. Readers love it when they’re unsure about what’s going to happen, so you use push-pull to keep them off-balance. Take the example I just used above. Han, Luke and Obi-Wan have gotten to Alderaan only to find that the planet’s been blown up. Now at this point in the movie, there’s been a lot of push. Our characters have been actively trying to get these Death Star plans to Alderaan. To have yet another “push” (“Hey, let’s go to this nearby moon I know of and regroup”) would continue the “push” and feel monotnous. So instead, the screenplay pulls, in this case LITERALLY, as the Death Star pulls them in. Now, instead of making their own way (“pushing”), something is happening TO them (“pull”). Another way to look at it is, sometimes your characters should be acting on the story, and sometimes your story should be acting on the characters. Use the push-pull method to keep the reader off-balance.

Escalation Nation

The second act is where you escalate the story. This should be simple if you follow the Scriptshadow method of writing (GSU). Escalation simply means “upping the stakes.” And you should be doing that every 15 pages or so. We should be getting the feeling that your main character is getting into this situation SO DEEP that it’s becoming harder and harder to get out, and that more and more is on the line if he doesn’t figure things out. If you don’t escalate, your entire second act will feel flat. Let me give you an example. In Back to the Future, Marty gets stuck in the past. That’s a good place to put a character. We’re wondering how the hell he’s going to get out of this predicament and back to the present. But if that’s ALL he needs to do for 60 pages, we’re going to get bored. The escalation comes when he finds out that he’s accidentally made his mom fall in love with him instead of his dad. Therefore, it’s not only about getting back to the present, it’s about getting his parents to fall in love again so he’ll exist! That’s escalation. Preferably, you’ll escalate the plot throughout the 2nd act, anywhere from 2-4 times.

Twist n’ Surprise

Finally, you have to use your second act to surprise your reader. 60 pages is a long time for a reader not to be shocked, caught off guard, or surprised. I personally love an unexpected plot point or character reveal. To use Frozen, again, as an example, (spoiler) we find out around the midpoint that Hans (the prince that Anna falls in love with initially) is actually a bad guy. What you must always remember is that screenwriting is a dance of expectation. The reader is constantly believing the script is going to go this way (typically the way all the scripts he reads go). Your job is to keep a barometer on that and take the script another way. Twists and surprises are your primary weapons against expectation, so you’ll definitely want to use them in your second act.

IN SUMMARY

In summary, the second act is hard. But if you have a structural road-map for your story (you know where your characters are going and what they’re going after), then these tools should fill in the rest. Hope they were helpful and good luck implementing them in your latest script. May you be the next giant Hollywood spec sale! :)

THE THIRD ACT!

THE GOAL

Without question, your third act is going to be a billion times easier to write if your main character is pursuing a goal, preferably since the beginning of the film. “John McClane must save his wife from terrorists” makes for a much easier-to-write ending than “John McClane tries to figure out his life” because we, the writer, know exactly how to construct the finale. John McClane is either going to save his wife or he’s going to fail to save his wife. Either way, we have an ending. What’s the ending for “John McClane tries to figure out his life?” It’s hard to know because that scenario is so open-ended. The less clear your main character’s objective (goal) is in the story, the harder it will be to write a third act. Because how do you resolve something if it’s unclear what your hero is trying to resolve?

THE LOWEST POINT

To write a third act, you have to know where your main character is when he goes into the act. While this isn’t a hard and fast rule, typically, putting your hero at his lowest point at the end of act two is a great place to segue into the third act. In other words, it should appear at this point in the story that your main character has FAILED AT HIS/HER GOAL (Once Sandra Bullock gets to the Chinese module in GRAVITY, that’s it. Air is running out. She doesn’t understand the system. There are no other options). Either that, or something really devastating should shake your hero (i.e. his best friend and mentor dies – Obi-Wan in Star Wars). The point is, it should feel like things are really really down. When you do this, the audience responds with, “Oh no! But this can’t be. I don’t want our hero to give up. They have to keep trying. Keep trying, hero!” Which is exactly where you want them!

REGROUP

The beginning of the third act (anywhere from 1-4 scenes) becomes the “Regroup” phase. This phase often has to deal with your hero’s flaw, which is why it works so well in comedies or romantic comedies, where flaws are so dominant . If your hero is selfish, he might reflect on all the people he was selfish to, apologize, and move forward. But if this is an action film, it might simply mean talking through the terrible “lowest point” thing that just happened (Luke discussing the death of Obi-Wan with Han) and then getting back to it. Your hero was just at the lowest point in his/her life. Obviously, he needs a couple of scenes to regroup.

THE PLAN

Assuming we’re still talking about a hero with a goal, now that they’ve regrouped, they tend to have that “realization” where they’re going to give this goal one last shot. This, of course, necessitates a plan. We see this in romantic comedies all the time, where the main character plans some elaborate surprise for the girl, or figures out a way to crash the big party or big wedding. In action films, it’s a little more technical. The character has to come up with a plan to save the girl, or take down the villain, or both. In The Matrix, Neo needs to save Morpheus. He tells Trinity the plan, they go outfit themselves with guns from the Matrix White-Verse, and they go in there to get Morpheus.

THE CLIMAX SCENE

This should be the most important scene in your entire script. It’s where the hero takes on the bad guy or tries to get the girl back. You should try and make this scene big and original. Give us a take on it that we’ve never seen in movies before. Will that be hard? Of course. But if you’re rehashing your CLIMAX SCENE of all scenes?? The biggest and most important scene in the entire screenplay? You might as well give up screenwriting right now. If there is any scene you need to challenge yourself on, that you need to ask, “Is this the best I can possibly do for this scene?” and honestly answer yes? This is that scene!

THE LOWER THAN LOWEST POINT

During the climax scene, there should be one last moment where it looks like your hero has failed, that the villain has defeated him (or the girl says no to him). Let’s be real. What you’re really doing here is you’re fucking with your audience. You’re making them go, “Nooooooo! But I thought they were going to get together!” This is a GOOD THING. You want to fuck with your audience in the final act. Make them think their hero has failed. I mean, Neo actually DIES in the final battle in The Matrix. He dies! So yeah, you can go really low with this “true lowest point.” If the final battle or confrontational or “get-the-girl” moment is too easy for our hero, we’ll be bored. We want to see him have to work for it. That’s what makes it so rewarding when he finally succeeds!

FLAWS

Remember that in addition to all this external stuff that’s going on in the third act (getting the girl, killing the bad guy, stopping the asteroid from hitting earth), your protagonist should be dealing with something on an internal level as well. A character battling their biggest flaw on the biggest stage is usually what pulls audiences and readers in on an emotional level, so it’s highly advisable that you do this. Of course, this means establishing the flaw all the way back in Act 1. If you’ve done that, then try to tie the big external goal into your character’s internal flaw. So Neo’s flaw is that he doesn’t believe in himself. The only way he’ll be able to defeat the villain, then, is to achieve this belief. Sandra Bullock’s flaw in Gravity is that she doesn’t have the true will to live ever since her daughter died. She must find that will in the Chinese shuttle module if she’s going to survive. If you do this really well, you can have your main character overcome his flaw, but fail at his objective, and still leave the audience happy (Rocky).

PAYOFFS

Remember that the third act should be Payoff Haven. You should set up a half a dozen things ahead of time that should all get some payin’ off here in the finale. The best payoffs are wrapped into that final climactic scene. I mean who doesn’t sh*t their pants when Warden Norton (Shawshank spoiler) takes down that poster from the wall in Andy Dufresne’s cell? But really, the entire third act should be about payoffs, since almost by definition, your first two acts are setups.

OBSTACLES AND CONFLICT

A mistake a lot of beginner writers make is they make the third act too easy for their heroes. The third act should be LOADED with obstacles and conflict, things getting in the way of your hero achieving his/her goal. Maybe they get caught (Raiders), maybe they die (The Matrix), maybe the shuttle module sinks when it finally gets back to earth and your heroine is in danger of drowning (Gravity). The closer you get to the climax, the thicker you should lay on the obstacles, and then when the climactic scene comes, make it REALLY REALLY hard on them. Make them have to earn it!

NON-TRADITIONAL THIRD ACTS (CHARACTER PIECES)

So what happens if you don’t have that clear goal for your third act? Chances are, you’re writing a character piece. While this could probably benefit from an entire article of its own, basically, character pieces still have goals that must be met, they’re just either unknown to the hero or relationship-related. Character pieces are first and foremost about characters overcoming their flaws. So if your hero is selfish, your final act should be built around a high-stakes scenario where that flaw will be challenged. Also, character piece third acts are about resolving relationship issues. If two characters have a complicated past stemming from some problem they both haven’t been able to get over, the final act should have them face this issue once and for all. Often times, these two areas will overlap. In other words, maybe the issue these two characters have always had is that he’s always put his own needs over the needs of the family. The final climactic scene then, has him deciding whether to go off to some huge opportunity or stay here and takes care of the family. The scenario then resolves the character flaw and the relationship problem in one fell swoop! (note: Preferably, you are doing this in goal-oriented movies as well)

IN SUMMARY

While that’s certainly not everything, it’s most of what you need to know. But I admit, while all of this stuff is fun to talk about in a vacuum, it becomes a lot trickier when you’re trying to apply it to your own screenplay. That’s because, as I stated at the beginning, each script is unique. Indiana Jones is tied up for the big climax of Raiders. That’s such a weird third act choice. In Back To The Future, George McFly’s flaw is way more important than our hero, Marty McFly’s, flaw. When is the “lowest point before the third act” in Star Wars? Is it when they’re in the Trash Compactor about to be turned into Star Wars peanut butter? Or is at after they escape the Death Star? I think that’s debatable. John McClane never formulates a plan to take on Hanz in the climax. He just ends up there. The point is, when you get into your third act, you have to be flexible. Use the above as a guide, but don’t follow it exactly. A lot of times, what makes a third act memorable is its imperfections, because it’s its imperfections that make it unpredictable. If you have any third act tips of your own, please leave them in the comments section. Wouldn’t mind learning a few more things about this challenging act myself!

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: (from Black List) An epic love story set in a time where a dying scientist is able to upload his consciousness into the internet and, facing its global implications, must fight against the forces who are actively working against the existence of a singularity.

About: This was one of the hottest projects in town last year, born from a script that sold for a lot of money. It became hot when Christopher Nolan’s longtime director of photography, wanting to make his directorial debut, attached himself. Johnny Depp signed up soon after. Then Morgan Freeman, the girl with the dragon tattoo’s sister, Kate Mara, and Iron Man 3’s Rebecca Hall. The film is in the can and will be hitting theaters in April, trying to grab that pre-summer sci-fi slot that’s proven so successful for a few projects. As for the writer, Jack Paglen, this is his breakthrough script! However, he didn’t start writing yesterday. He actually had a script on the 2007 Black List, with 3 votes (called “Joy”), and was teaching screenwriting at the New York Film Academy in L.A. (isn’t that an oxymoron?) while writing Transcendence. Transcendence finished with 7 votes on 2012’s Black List.

Writer: Jack Paglen

Details: 5/01/12 – 131 pages

This is not the first time I’ve seen this idea. In fact, I’ve seen people trying to crack this story (or stories like it) for awhile. There was even a huge spec written in the 1990s by Kyle Wimmer that tackled very similar territory. But without question, Transcendence transcends the idea. Paglen cracks it. All of the pitfalls inherent in this concept (which there are many of), he found ways around them. To understand this script, you have to imagine 2001 occurring here on earth. On a global scale. Sound ambitious? Well, this is an ambitious script. And while I wouldn’t put it in the category of “great,” I’d say it’s pretty damn good.

30-something neurosurgeon Max Waters is one of a handful of scientists across the world who is making strides in artificial intelligence. Their goal is to reach the “Singularity,” a nerdy term for when computers become as smart as humans. From there, it’s assumed, computers will become twice as smart as humans, then four times, then eight, then 16, and so on very quickly, til the point where their intelligence level will literally allow them to do anything, and anything may include getting rid of us.

Which is exactly why a renegade group out there known as the “RIFT” is trying to assassinate these geeks. They believe once the singularity is reached, our planet will be in danger. They manage to kill most of these scientists, but strike out with Max. They do manage to shoot Max’s best friend, Will, however. Lucky for Will, the shot is a flesh-wound. Unlucky for him, the bullet is laced with uranium. Will (who I’m assuming will be played by Depp) will be dead in weeks from radiation poisoning.

Will’s wife, Evelyn, however, is very close to figuring out how to copy an organic brain into a digital drive. And she gets this wild idea that they should do this for Will before he dies! Max thinks this is way too weird, but Evelyn is so passionate about it that he goes along with it. We also get the feeling that Max has a bit of a crush on Evelyn, and that he’ll do anything she asks.

A week later, Will dies, but Evelyn gets him copied by the skin of her teeth. Naturally, it’s a little weird talking to your husband when he’s inside of your PowerMac, but I guess it’s not that different from Skype, right? I mean, outside of the fact that he’s eternal and lives inside the internet and controls the stock market? Besides that, it’s just like any other form of electronic communication.

It doesn’t take Will long to realize what he’s capable of. So he starts making money off the stock market, transferring that money to offshore accounts, having materials shipped to an area in the middle of the desert, and paying construction crews to come there and start building a new “super-town/base” with those materials.

Max gets creeped out by Will’s aggressive need to expand, and warns Evelyn to shut him down. But there’s no way Evelyn’s killing her husband, even if she knows he’s acting like a Digital Hitler. Oh, but it gets worse. Since Will has all the information and knowledge and intelligence in the world at his finger…err, at his keyboard-tips, he’s able to build a new breed of nanotechnology that starts building shit on its own.

He uses this technology to infiltrate his workers, essentially making them slaves, and turning them into extensions of himself. And once his mini-city starts coming together, Will is able to create a hologram of himself, so he can be right there by his wife’s side.

Back in the boondocks, Max has realized just how dangerous Will has become, so has teamed up with the group who originally tried to kill him, the RIFT. Let bygones be bygones, right? I always forgive the people who try to kill me.

The RIFT are far far FAR off the grid so that Will can’t touch them. But the stronger Will gets, the less that will be the case. Everything is controlled by computers. Which means Will can use just about anything to mount a strike. Knowing this, Max and the RIFT put together an all-or-nothing offensive to take down Will’s stronghold. They know they’re only going to get one shot. And if they fail, humanity is doomed.

We were talking about set-pieces awhile back on Scriptshadow, how they need to be big and original. Transcendence showcases what this means with one of the cooler action scenes I’ve seen on the page. In it, the RIFT attack Will’s base. They utilize old cannons that can’t be controlled by computers. When the cannons shoot, the nanotech move towards the target area, creating a blockade. When some shells do get through, blowing parts of the building up, the nanotech quickly rebuild the damaged area. At the same time, Will’s men are being controlled by nanotech, allowing them to run at lightning speed, exhibiting feats at 100x an average man’s strength. So they’re throwing cars, bashing tanks. I could see that scene playing in the theater now. It would be AWESOME!

But what surprised me the most about Transcendence was that it was driven by a really heartfelt story – this broken love between Will and Evelyn. I loved the conflict going on within Evelyn, how she knew Will was going too far, and that the right thing was to shut him down, but she loved him too much to do that. Conflict within characters is always good!!!

But on top of that, Paglen created conflict BETWEEN the characters, specifically in that Max loved Evelyn. So his choices were never easy either. Was he telling Evelyn to shut down Will because Will was getting TOO dangerous? Or was he telling her to do it because he wanted Evelyn all to himself? These are the kind of nuanced character issues you want to be setting up in every script! Plot only interests a reader so much. It’s the people within that plot that truly draw us into a story. If those people don’t have anything interesting going on between each other, then who gives a shit?

We also talked about (in that set-piece article) putting things in your blockbuster script that producers can see in the trailers. Once characters started getting rigged with nanotech and had super-human abilities, shit just got cool. I can see how that’s going to look onscreen – them knocking around tanks and cars in the middle of the desert. It’s going to sell tickets. There’s no question about it.

The script also reminded me that a good writer can take his time getting into his blockbuster. Paglen doesn’t hit us with anything huge right away. He builds slowly. We do have things happening (assassinations and assassination attempts) but much of the first 40 pages is dedicated to Will being transferred into the computer and understanding his new powers. After that though, the script really builds (remember – a blockbuster must build!) in exactly the manner any big movie is supposed to.

The only reservations I have about the script are logic-related. Why didn’t the army come over and take down Will’s base? How was this huge thing allowed to be built up over so long a period of time without any interference? I know most of the army’s equipment is run by computers but you’d think they’d still TRY. The army doesn’t even make an appearance here, which I found to be a little strange.

In the end, Transcendence contains excellent execution, good characters, a heart at its center, and some great never-before-seen action scenes. Assuming Pfister’s direction is as strong as his cinematography, this should be a can’t miss film.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Every idea, whether it be a character or a relationship or an action set-piece, has a known ceiling. This ceiling is where any average person would take it. Your job, as a writer, is to go beyond that ceiling, to the places the average person never would have thought of. That’s what makes you a writer, is that you see things other people don’t. So here, most writers would’ve placed Will in the computer and had him start screwing with the banks and using public cameras to follow his enemies (something very “Eagle Eye-ish”). That’s expected. You have to go beyond that. I believe the nanotech really brought this story to the next level. I wasn’t expecting it, and was surprised when it had such a strong impact on the story (and the action!).