Search Results for: F word

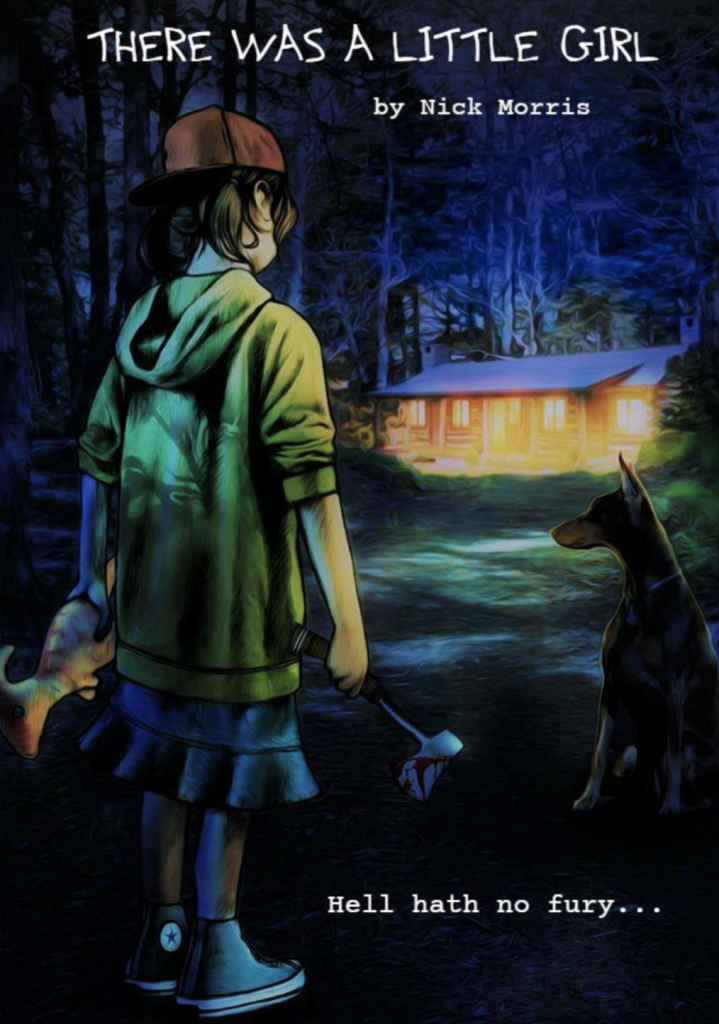

Are you ready… for Die Hard with a 9 year old girl?

Genre: Horror/Thriller

Premise: After witnessing the murder of her daddy, nine-year-old Becky and her dog set out to teach the scumbags responsible that Hell hath no fury like a pissed-off little girl with nothing to lose.

Why You Should Read: It’s my belief that somewhere deep within the human psyche there exists a zone of intense fury that, thankfully for most of us, will never manifest itself. A level of rage that can only be triggered by a morally reprehensible and personal transgression – like the murder of a loved one. That’s the core idea that kept insisting I write this script. And the most compelling perspective I could think of to explore that idea from was that of a young kid. So I knew going in that it could be polarizing and striking the right tone would be tricky. But I’m very pleased with how it’s come together and would really love to hear the thoughts of the ScriptShadow community. Thanks for looking!

Writer: Nick Morris

Details: 93 pages

A long long time ago I remember seeing a trailer for a movie called “Blue Streak.” It starred the great one himself, “Big Momma’s House” actor Martin Lawrence. The setup for the movie was: Martin Lawrence’s criminal protagonist knows the police are about to catch him for stealing a diamond, so he hides the diamond in the ceiling of a building under construction. He’s later caught and sent to prison. Two years later he gets out and comes back to retrieve the diamond. Only now the building is… a police precinct. So Martin Lawrence must pose as a cop to retrieve the diamond.

When I saw that trailer, I thought to myself, “That has to be the greatest setup for a movie ever!” I mean, what a clever concept. Now since then, I no longer believe it’s the best idea ever. But it’s still a damn crafty idea. As a plot device, it’s as clean a setup as you’re going to get. Someone has to ditch something illegal then come back to get it later, except now the conditions aren’t ideal for retrieval.

That’s the setup for today’s script. But the question we’re all wondering is, can it survive without a role for Martin Lawrence?

Jeff is driving his 9 year-old daughter, Becky, up to their cottage with their two dobermans, Diego and Dora. Becky’s still reeling after the death of her mother and is furious that Jeff is bringing up a new woman for Becky to meet, Kelly. Jeff assures Becky that no one can ever replace mom, but to please give Kelly and her 5 year-old son, Ty, a chance.

Becky’s not having it, storming off to her tree-house after Kelly and Ty arrive. Little does Becky know, her tantrum may have saved her life. Four escaped convicts, leader Dominick, muscle Apex, pervert Cole, and pedophile Hammond, descend upon the house looking for a key Dominick hid there ten years ago.

The four rough up Jeff, Kelly, and the kid, asking for the key, before Dominick realizes a young girl is out there, and she may hold the literal key he’s been looking for. So Dominick sends his boys out to go look for her, but Becky quickly outsmarts them. And when she gets Cole in a compromising position, she slams a broken wine-glass handle through his eye, killing him. It’s on!

(spoiler) Unfortunately for Becky, Dominick blows Jeff’s head off, which technically makes Becky an orphan. It also makes her pissed. So while Dominick’s men run around the property in search of that key, Becky runs around in search of revenge. And she’ll use any graphically violent means possible to get it!

One of the things we talk about here is irony. A big tough muscular guy working as a bouncer is expected. A small weasly geek with glasses working as a bouncer, and being good at it, is ironic. You’re looking to add irony wherever possible in a screenplay because it’s one of those things that, when done well, works like a charm.

Nick took that route here. Instead of a tough-as-nails New York Cop running around a property killing bad guys, Nick inserts a clever 9 year-old girl. It’s ironic, so it’s good, right?

Well, the thing with screenwriting is that sometimes rules collide. Something you’re told you should do overlaps with something you’re told you should never do, and a judgement call needs to be made. You can make the argument that There Was A Little Girl violates one of the most important rules in screenwriting: suspension of disbelief.

Is it believable that a 9 year-old girl could take down a group of big burly criminals in a non-comedic setting? I’d have a tough time believing that 9 year-old girl would have the strength to even stab someone with a wine glass handle.

However, there may be a solution to this. One thing I could buy into was a 9 year old girl with two full-grown trained Dobermans killing a group of men. If you kept both dogs alive and she used them for the bulk of her attacks, I might be able to buy into that. Maybe they were even fight dogs that Jeff rescued. So they have killing in their DNA.

The thing I’m more concerned with in There Was A Little Girl, though, is the dialogue. It lacks color. Throughout the first half the script, almost every line of dialogue is very basic, one or two lines. There’s zero spice. Here’s an example. Jeff greets Kelly when she arrives…

“Man, I have been waiting for this.” “Me too (looks around) Wow, you weren’t lying. This is beautiful!” “Thanks. You found it no problem?” “Yeah, well, I found it. Your sketchy-ass directions were no help. Thank God for GPS.”

‘Sketchy-ass directions’ is as colorful as the phrasing gets in this script. And it’s rare.

Look, dialogue has always been a weakness of mine. I’m aware of how difficult it is to write. But you at least have to try. Add some color SOMEWHERE. Here’s Dominick’s longest chunk of dialogue in the script: “Christ. I do not need this shit right now, Apex. Okay? There’s no time. There’s just no fucking time. I’ve been here too long already. They’ll be out searching by now. Door to door. Even if they don’t remember this place, they’re still gonna eventually show up here. Right?!”

The sentences are all very short, very to-the-point. There’s zero color. Check out Tommy Lee Jones’s famous line in The Fugitive: “Alright, listen up, ladies and gentlemen, our fugitive has been on the run for ninety minutes. Average foot speed over uneven ground barring injuries is 4 miles-per-hour. That gives us a radius of six miles. What I want from each and every one of you is a hard-target search of every gas station, residence, warehouse, farmhouse, henhouse, outhouse and doghouse in that area. Checkpoints go up at fifteen miles. Your fugitive’s name is Dr. Richard Kimble. Go get him.”

Is it fair to compare Dominick’s line to one of the most popular movie lines in history? No. But I’m trying to make a point. You need to do more with dialogue than just keep the plot moving. Especially in a script like this where you have criminals. Criminals are ideal vessels for spouting colorful dialogue. That’s the first thing I’d tell Nick to do here – do a dialogue pass and FIND THESE CHARACTERS’ VOICES!

Lastly, the plot is too predictable. I was way ahead of the script, often waiting for the writer to catch up to me. (spoiler) Jeff’s death might have been a surprise had I not read the logline. But that was it.

I’ve found that you can sometimes get away with a predictable plot. But only when the character development is strong. In other words, you’ve got to give us one of the other. You can’t give us neither. And There Was a Little Girl had neither. Apex’s conscience was the closest thing we got to a character arc. We needed more.

This is the second amateur script I’ve read in a row (not last Friday’s script, but a consultation) where the writer could’ve benefited from more time with the characters before the inciting incident. That would’ve allowed us to give the characters clearer flaws so we knew what they needed to work on. I know everyone’s afraid that if they start the script too slow that the reader will get bored. But if you give us a teaser that rocks our world (and There Was a Little Girl had a pretty good teaser), you can take your time setting up the characters before the inciting incident occurs. I barely knew Kelly before Dominick showed up. And since she’s the one who survives between her and Jeff, that was a problem, since I could care less about a woman I barely knew.

I like the marketing image of a girl (who will need to be older) with two vicious dobermans staring into a house at night. But this is a tricky one. Will people buy tickets to a movie with this young of a lead that’s this violent?

Script link: There Was A Little Girl

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: How do you add color to dialogue? Here’s a trick. Think of all the people in your life, past and present, who have weird/unique/fun/interesting ideas/thoughts/speech-patterns/obsessions. Find one that’s similar to your character and write the character the way that person speaks. I was briefly friends with a guy who’d spent a year in China. All he could talk about when you brought up anything was how differently they “did it in China.” It became so annoying that I Peking ducked out of that friendship. However, those are the types of people you’re looking to for inspiration if you want to add color to dialogue.

Looking for a great idea for your next script? You can attempt to come up with that rare genius concept that, somehow, after 100 years of cinema, nobody has thought of yet. OR you can take cinema history and make it work for you.

One of the best ways to come up with a kick-ass movie concept is to find something that did well at least 20 years ago (an adequate amount of time for everyone except cinema geeks to have forgotten about it), and reinvent it.

I’m not talking about remakes here. No no no. Not only are those unoriginal. They’re also costly. You actually have to have the rights to the movie to remake it. Instead, you take an old movie concept and you change one or two of the key variables, inventing a totally new movie!

You guys remember Taken, right? Guy goes to save his kidnapped daughter? That movie was a reinvention of the Arnold Swarzenegger movie, Commando. The classic film, Rear Window? It’s been reinvented a number of times. For example, in 2007, with the film Disturbia. They changed the age of the hero (from a man in his 30s to a teenager) and the reason he was stuck in his house (he had an ankle monitor instead of being in a wheelchair).

Now, not every movie was meant to be reinvented. The Eddie Murphy movie, Coming to America, is too goofy to be made today. E.T. was so specific to the 80s, a current version wouldn’t work. Auteur-driven movies, like Pulp Fiction, also lack reinvention DNA.

But there are lots of movies that are perfect for reinvention. Jordan Peele (Get Out) reinvented Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner simply by changing the genre to horror. Dan Gilroy reinvented Taxi Driver by placing his hero in a late night news van instead of a cab (Nightcawler).

But there is no perfect formula for reinvention. You simply look at an old movie and start asking “What if” questions. What if I changed the genre? What if I changed the age of the hero? What if I added a supernatural twist? What if I moved it from the city to the country? What if I told the story from a different character’s perspective? The amount of questions you can ask is endless. Just keep going until you find something cool.

To get you started, here are 10 movies ready to be reinvented for modern audiences. I’m going to rank them from weakest to strongest. Care to guess the number 1 suggestion? It has been the movie Hollywood has been trying to reinvent for over two decades now. And nobody’s figured it out. Will you?!

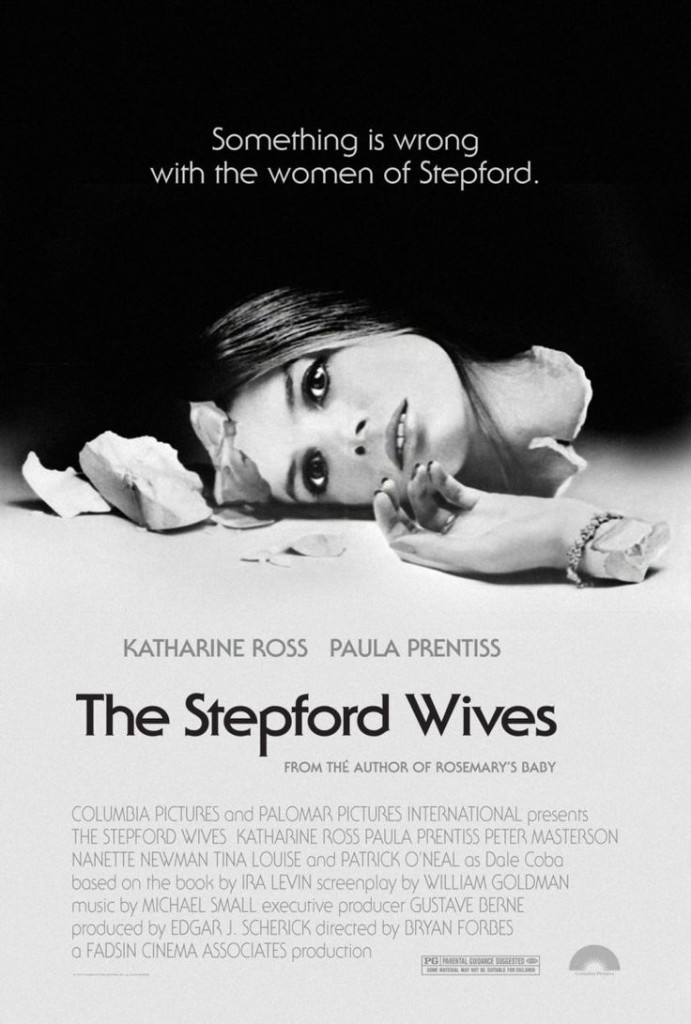

10 – The Stepford Wives – I like horror that lives just off the main strip. Get Out is a perfect example of that. It’s nontraditional horror. As far as I’m concerned, suburbia is an underutilized element in horror. Suburbs can be terrifying. And it seems like we’re living in a new age where a suburb involved in a horrific conspiracy can make a huge statement about society. And scare the hell out of us in the meantime.

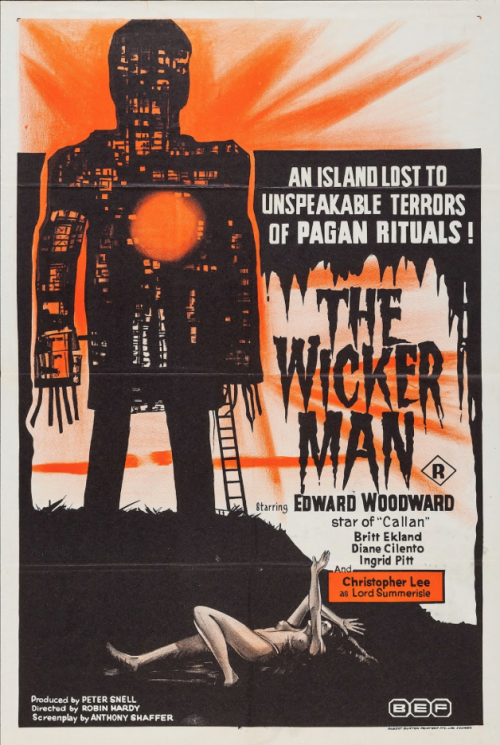

9 – The Wicker Man – Dude goes to an island to look for a missing person. Bad shit happens. The marketing is already gift-wrapped for you. Not sure you’d be able to get away with the musical element. But there are plenty of other variables to play with here.

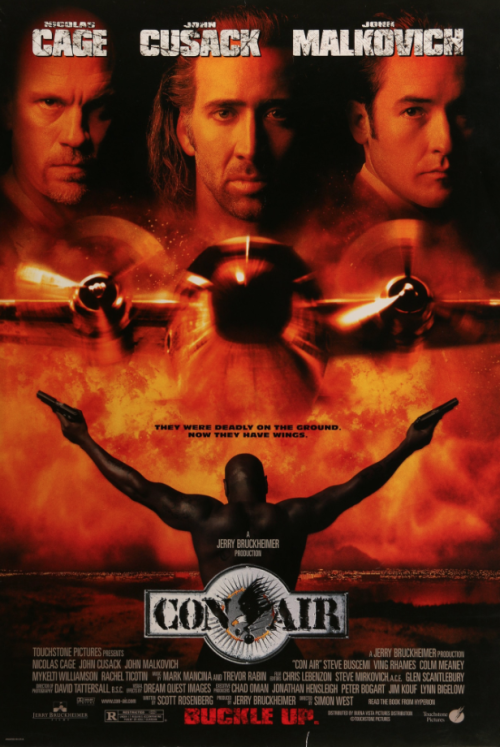

8 – Con Air – Mark my words. At some point, the Jerry Bruckheimer high concept craze will come back. What was so great about Con Air, though, is that the concept was less about the plot than it was about the characters. That’s where the potential for this reinvention comes from. A large group of dangerous characters in a situation where they could do some major damage.

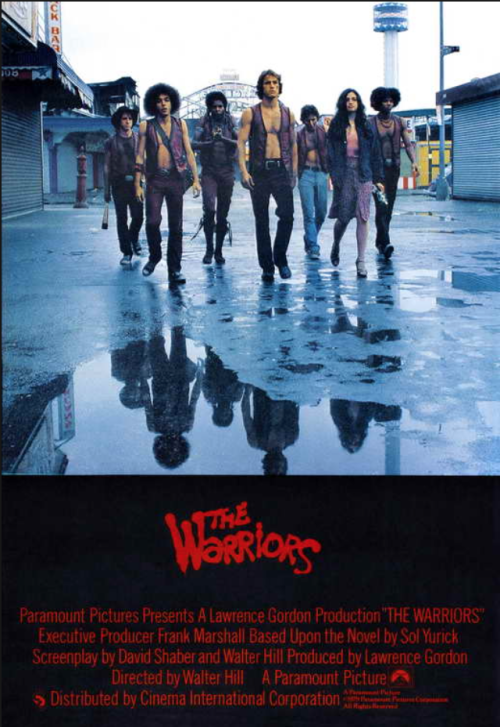

7 – The Warriors – Why nobody’s tried to reinvent this movie is beyond me. You have people marked for death trying to get across a gang-ridden city. It’s got GSU up the wazoo. I don’t think you could be as goofy as they were (mimes on roller skates). But who says you can’t make it a straight thriller?

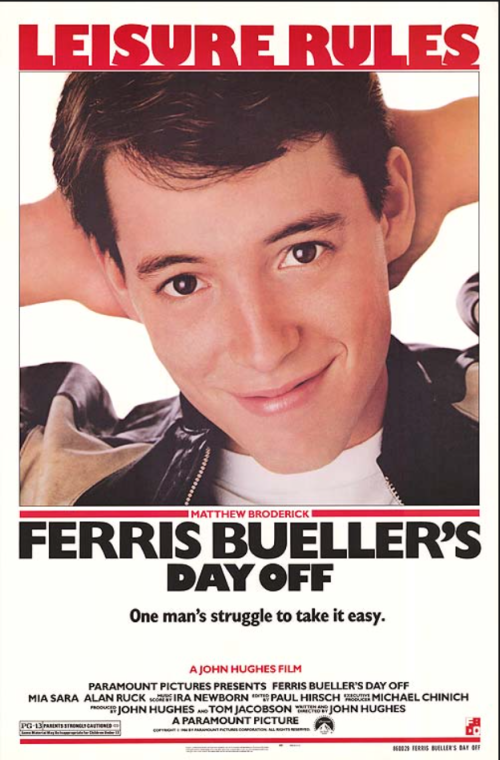

6 – Ferris Bueller’s Day Off and The Breakfast Club – It baffles me these two movies haven’t been reinvented. They’re both pretty light on the concept side, so there’s room to play with the idea. But a movie that centers on a popular high schooler doing something crazy seems like box office gold to me. The Breakfast Club is a little tougher, since it’s been referenced so much. You’ll probably need to think outside the box some. But not only would this kill if executed well, but it would be cheap to shoot! So if you came up with a great concept, you could fund it yourself.

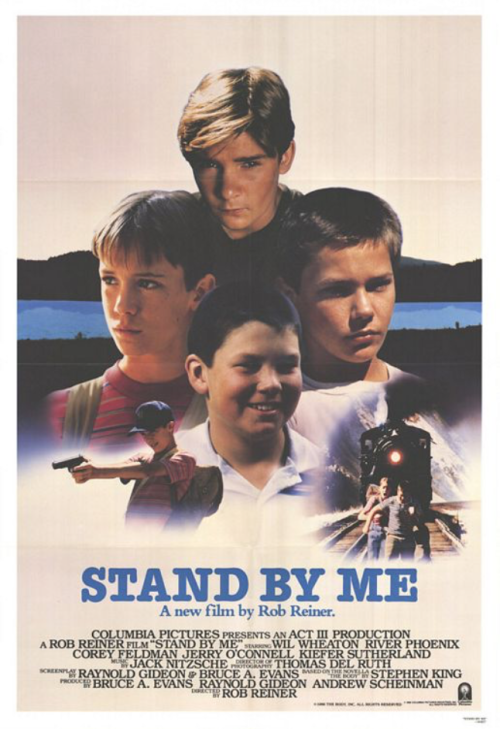

5 – Stand by Me – There’s room for a movie about kids on a grounded adventure that’s heavy on character development. Of course, since this is a reinvention, who says they have to be kids? It’s up to you!

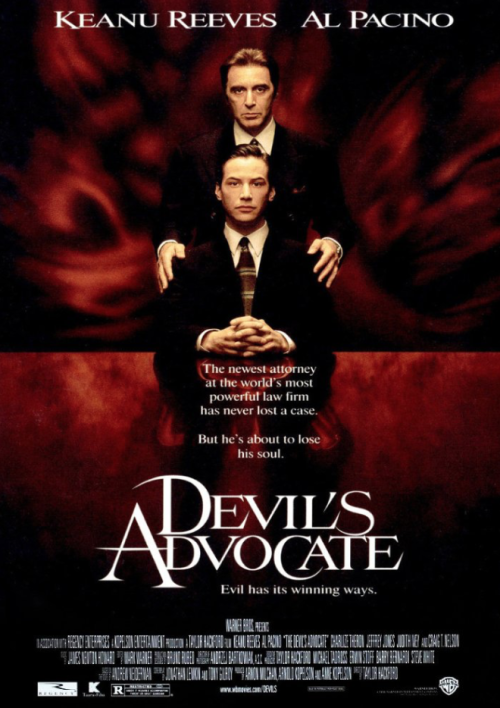

4 – The Devil’s Advocate – I love these high-concept two-handers they don’t do anymore. I feel like The Devil’s Advocate is ripe for a “Get Out” like makeover.

3 – The Apartment – I don’t think you can reinvent When Harry Met Sally because there’s no concept to reinvent. But something like The Apartment could work. A love story along the lines of When Harry Met Sally, but with a hook to keep the story focused and fun. It seems like with all these apps and changes in the way we do real estate (Air BnB?) that there’s something to play with here. But, again, that’s the top-of-my-head idea. A good writer digs deep and finds that creative option that truly breathes new life into the premise.

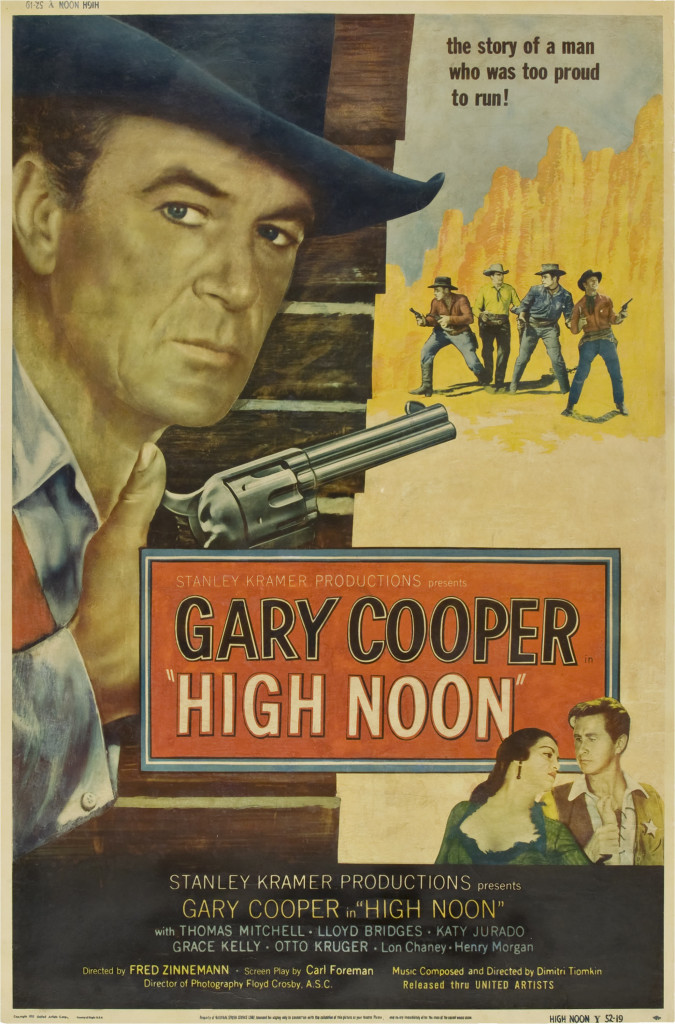

2 – High Noon – You guys have heard me talk about this one before. I’m dying for a modern-day reimagining of this idea. The mayor of Chicago finds out that the criminal whose life he destroyed got out of prison on a techicality and arrives in the city at noon. Word on the street is that he’s already paid off members of his staff to kill him. He has to decide whether to flee or stay. Or, you know, your own reimagining. This concept probably has the single best structure for a movie.

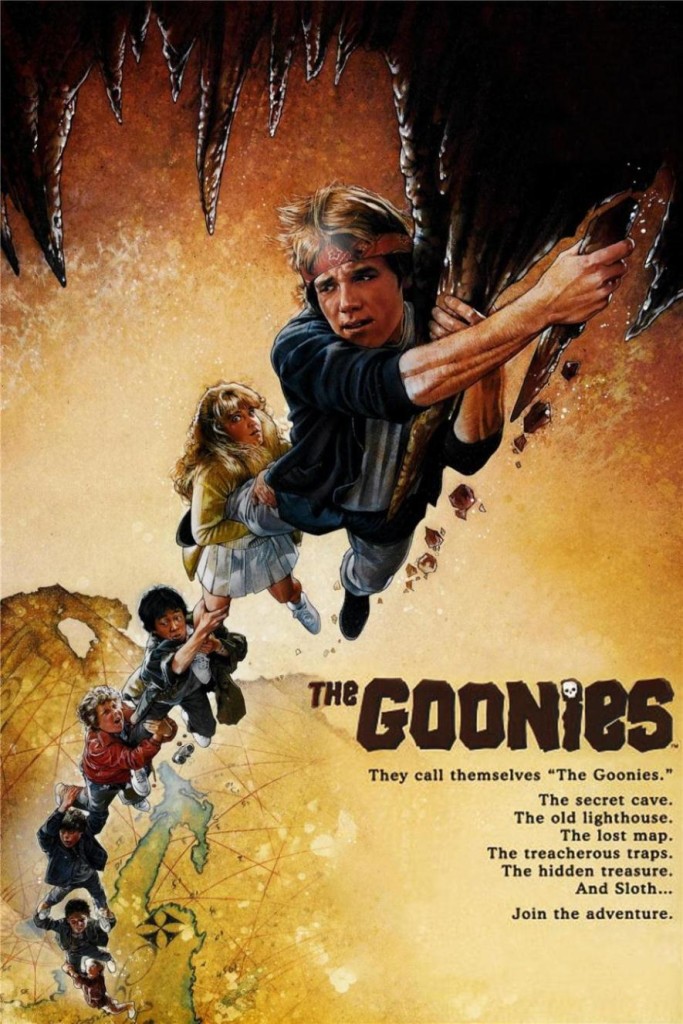

1 – The Goonies – Somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 Goonies-like specs have sold in Hollywood since the original film came out. And yet… no one’s been able to crack the reinvention. There’s a reason for that. The things that made that movie so great are very specific. A group of quirky kids on an adventure. They’re looking for a treasure. The treasure is hidden in an elaborate labyrinth beneath the town. If you write a story too close to that, it looks like you’re just ripping off The Goonies. How do you REINVENT the concept? Whoever figures that out will be rich beyond their wildest dreams.

Offer up your reinvented loglines of the above movies. Upvote your favorites. Also, let me know what movies you think should be reinvented!

If you’ve got a logline you want feedback on, I rate, give analysis, and rewrite loglines for $25. $75 for a pack of five. I don’t sugarcoat. I give you the real deal on whether you should write the script or not. Contact me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “LOGLINE” for a consult!

How crazy is this? We just had an AOW winner with a revenge-obsessed young girl. What’s the first script on this week’s list? A revenge-obsessed young girl! I actually wasn’t going to include the script for that reason. But it’s written by Nick Morris. And we all know he’s one of the best writers on Scriptshadow. Still, this is a reminder that we need to push ourselves with our concepts. If we’ve thought of it, somebody else has probably written it. So what’s that idea you know nobody’s thought of yet? Let’s see that one.

Another unsolicited tip since I’ve been seeing a lot of it in the submissions: Stop telling us this is your first script! Or telling us this was your first script and you’re dusting it off with another rewrite. First scripts are always bad. There’s been like three good first scripts in the history of movies. As soon as someone says this was, in any way, their first script, I know not to post it. Come on guys. Sell yourselves!

For those of you new to these parts, here’s how Amateur Offerings works: Read as many of this weekend’s scripts as you can and vote for your favorite in the comments section. Winner gets a review next Friday.

If you’d like to submit your own script to compete on Amateur Offerings, send a PDF of your script to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the title, genre, logline, and why you think your script should get a shot.

Title: THERE WAS A LITTLE GIRL

Genre: Horror/Thriller

Logline: After witnessing the murder of her daddy, nine-year-old Becky and her dog set out to teach the scumbags responsible that Hell hath no fury like a pissed-off little girl with nothing to lose.

Why You Should Read: It’s my belief that somewhere deep within the human psyche there exists a zone of intense fury that, thankfully for most of us, will never manifest itself. A level of rage that can only be triggered by a morally reprehensible and personal transgression – like the murder of a loved one. That’s the core idea that kept insisting I write this script. And the most compelling perspective I could think of to explore that idea from was that of a young kid. So I knew going in that it could be polarizing and striking the right tone would be tricky. But I’m very pleased with how it’s come together and would really love to hear the thoughts of the ScriptShadow community. Thanks for looking!

Title: Perfect

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Logline: An ex-con kidnaps his estranged transgender daughter in a last ditch attempt to provide the male influence he was never around to.

Why You Should Read: I have a transgender sister and have always found her difficult relationship with my father to be an intriguing dynamic. Especially because she’s very feminine and he’s the kind of unrelenting asshole who goes out and looks for trouble like he was built in a lab by fascist robots. I’ve been writing off and on for almost ten years, have had some pretty big actors and agencies request my work on strong word of mouth over the duration, but unfortunately nothing has ever quite come together. I’m not sure why my heart seems to always get suplexed down the final straight of negotiation but it seems to be either just bad timing market-wise, or the benevolent influence of the league of shadows. After all, as we know; those guys are everywhere. Anyway, I believe that this is the best thing I’ve ever written. Plus I just accurately used a semi-colon. Believe in me!

Title: Adolf H.

Genre: Alternative History

Logline: A fictional version of what could have happened if Adolf Hitler (as a young and aspiring painter) had been accepted at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

Who are you and why should I read this: I’ve been trying to write this script for a very long time. It’s one of my most serious efforts at creating something different. I know the subject might put some people off. But I believe it’s a very interesting “What if?” I’m in dire need for some feedback!

Title: Battle God

Genre: Sci-fi

Logline: In 2050, an illegal dark web video game lets unmodified humans fight for cybernetic upgrades inside shooter, racing, survival horror, and SIMS mini games.

Why You Should Read: Congratulations! You have been invited to play Battle God. Battle God is an open-source video game where controllers navigate unmodified human players through mini-levels to win cybernetic upgrades. Win a spot at Blue Genesis, today! New round starts in 02:00:00. If you back out at any time, you will be killed. Do you wish to play? Yes/No.

Title: A Decent Man

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Logline: Michael’s perfect life is turned on its head when he discovers that his loving wife is trying to kill him. Still in love with her, he tries to uncover why. What he finds on his journey is a truth that changes everything.

Why You Should Read: This is a deeply moving, character driven story about the bonds of friendship and the redemption of a lost man. With a tightly structured plot, three dimensional characters, witty dialogue, more twists than an average drama should afford, and a heck of a third act; A Decent Man delivers an emotional experience that’s brought almost all who have read it to tears. As a bonus, its been optioned by an award-winning director. Thank you for your consideration.

This is one of the toughest questions screenwriters face. You spend 6-12 months writing a screenplay. You send it out to a few close friends, maybe a couple of industry contacts, and the initial feedback isn’t bad, but it isn’t great either. One thing is clear though. Your script isn’t the runaway hit you thought it was. No worries. You take that feedback, do some rewriting, address the major concerns, come back, send it out to those people again (if they agree to read it that is) and the response is… still a bit tepid. “Yeaaahhhh. This is a littttlllle better. But I don’t know. There’s something missing.”

All of a sudden, a terrifying prospect hits you. You may have just wasted an entire year of your life on a screenplay that nobody wants a part of. Do you ditch the script and move on to the next one? Or do you put in yet another rewrite in the hopes that you can elevate the script to the potential you know it has?

Before I help you answer that question, I want to say that making this choice is an imperfect process. A lot of it is based on feel. And I’ll give you a prime example of that. There was a script I reviewed a couple of weeks ago called “Final Journey.” You may remember it as the “Eskimo Hand Job” script.

I would later learn that the writer had written that script a decade ago. It placed well in some contests but nothing came of it so he moved on, writing a dozen other scripts over the years. Then he decided to dust the script off and enter it into a few contests. At Page, the script tapped out in the third round, but one of the judges was a respected manager who absolutely loved it. That love led to a signing, the manager blasting the script around town, and the script subsequently making the Black List.

The point is, all script success stories funnel back to an early champion, someone with notoriety who can bring attention to the script. And you never know who that person is going to be. However, there are ways if to gauge if your script is good enough to find a champion. The last person you want to be is the guy parading the same script around town year after year, insisting that its genius hasn’t been recognized yet.

So, here are some tips you can use to gauge whether you should keep pushing your script out there or move on to the next one.

Is this one of your first three scripts? – I’m not going to say it’s impossible to write a great script in your first three tries. But it’s hard. Those first three scripts are somewhat of an education period for screenwriters that help them become familiar with screenwriting’s unique format. This is not the determining factor in whether to move on or not. But it is a factor. If there’s little interest in your script despite a lot of reads and it happens to be one of your first three scripts? Consider moving on.

Have you done everything in your power to get your script out there? – I’ll never forget this one newbie writer who spent three years writing a fantasy script, then afterwards, sent it to the five industry contacts he’d accumulated in that time (all of them friends-of-friends-of-friends), and when all five of them came back with, “No thank you,” he packed up, said that Hollywood was a town run strictly by nepotism, and moved back home. I mean, come on! You have to understand that this is a town addicted to the word, “No.” Steven Spielberg gets told no. JJ Abrams gets told no. As a nobody, you’re going to get a lot of nos. The only way to combat this is to explore every avenue – contests, online services, Scriptshadow, friends of friends in the industry. If you haven’t gotten your script out to at least 10 people (and preferably a lot more), you have no idea if your script is worth continuing to pursue.

Identify honest feedback – Part of figuring out whether to stay in a script relationship or cut ties is gauging feedback. If the feedback’s good, stay. If it isn’t, go. Here’s the problem though. Not all feedback is honest. In fact, most feedback is given with kid’s gloves, so as not to hurt the writer’s feelings. For this reason, whatever a reader’s evaluation is, assume it’s worse. I’ll never forget one of my friends giving me nice polite feedback on a script once and thinking, “Wow! This script isn’t that far off!” Five years later I was out drunk with that same friend, and the script came up. He launched into this randomly angry monologue about how my script was nearly impossible to get through because of how bad it was. He ended with, “I’m so glad you moved on from that thing.” Yikes. I had no idea he hated the script that much. It was a reminder that people don’t want to hurt your feelings. With that in mind, there are a few things to look for during feedback. If feedback (written or oral) is polite, repressed, or apathetic, you’re in trouble. If there’s genuine excitement, an eagerness to recall favorite moments, or the reader wants to know what you’re going to do with the script next, that’s an indication it’s a script worth fighting for. (side note: always consider the source. If you send your comedy spec about a man who sleeps with 100 women in one weekend to a woman who identifies herself as “The Internet’s #1 SJW,” she’s probably going to hate your script no matter what)

How big are the script’s problems? – In trying to figure out if you should rewrite your script yet again, you need to identify how much work is involved. The more work, the more time. The more time, the more you should consider the script a sunken cost and move on. If you’re hearing feedback like, “The entire second act drags,” or, “I don’t understand your main character,” that’s major rewrite territory there. If it’s stuff like, “You need an extra scene to beef up the love story” or “I would combine 5th Most Important Character with 7th Most Important Character,” those changes can be made fairly quickly.

Be honest with yourself – Every script is a like a baby to a screenwriter. It doesn’t matter if he’s the ugliest baby in the city. He’s still YOUR baby. But the difference between an ugly baby and an ugly screenplay is that you don’t have to raise an ugly screenplay. So do me a favor. Step outside of your subjective reality – the 500 hours you’ve spent on the screenplay, the trailer you can’t wait to see in the theater for the first time, that brilliant devastating scene at the end that’s going to have the audience in tears – and look at the objective reality. Are the people reading your script feeling even a fraction of what you’re feeling? One of the biggest reasons writers stick with scripts that don’t deserve to be stuck with is that they’re not honest with themselves. Stop looking at your script through rose-colored glasses.

If this article has helped you realize it’s time to move on from your current screenplay, I have a couple of happy thoughts to leave you with. Every time you write a new screenplay, you become a better writer. So you should be excited about writing something new. Also, no screenplay is ever truly dead, as the Eskimo Handjob script reminds us. Once you sell a script, tons of people are going to want to read whatever else you’ve got. That’s when you bust out your old stash of screenplay gems.

A few weeks ago in Amateur Offerings, a Scriptshadow reader brought up that one of the entrants had such a clunky writing style, it was difficult to understand even his most basic sentences. While this is something that happens a lot at the beginner level, you’d be surprised how often I encounter this problem from writers 4, 5, 6 years into their journey.

It’s my belief that these mistakes are made because the writer isn’t aware that their writing is clunky. Usually it’s because that writer isn’t getting enough feedback. But even for the writers putting their work up here, it’s embarassing to tell someone that their writing is at an eighth grade level. It’s easier to focus on some other problem they need to fix. The writer, then, blissfully unaware, continues to write ugly clunky difficult-to-read screenplays.

So today I want to go over the formula for writing a smooth easy-to-read script. Now it’s important to note that the foundation for good writing comes from education. I’m not going to teach you what a noun or a verb is. But even if you aced your AP English class, you still want to keep this formula in mind. Here it is…

Simplicity + Clarity + Voice + Skill = Readability

Let’s go over each of these in detail.

SIMPLICITY

This is the basis for all easy-to-read writing. Keep your sentences simple. The way to do this is to start with a baseline. Whatever you’re trying to say, say it as simply as possible. Don’t phrase your sentence in a weird way. Don’t add a bunch of unnecessary gunk. Give us the action as if you were explaining it to a 3rd grader. So if you want to say that John Wick shoots and kills Frank, write out the most basic version of that sentence as it relates to the scene.

John grabs his gun off the counter and shoots Frank in the head.

This might not be the final sentence you go with. It may need more meat, more punch, more flash. But we’ll get to that. The idea here is to convey what’s happening to the reader as simply as possible. What you don’t want is something like this…

John grabs the jet black gun with authority, piercing Frank between the eyes with a bullet out of hell, who’s dead before he even knows what hit him.

This sentence is technically correct but there’s too much information and it’s a bit of an awkward read. The more words you’re adding, the more commas you’re adding, the more actions you’re adding, the more complex you’re making your sentence. If you keep things simple, you don’t have to worry about clunky sentences. If you want to read a script that embodies this approach, check out Vivien Hasn’t Been Herself Lately, which someone in the comments section should be able to point you towards.

CLARITY

If your writing isn’t clear, forget about us liking your script. We won’t even like your first page. Lack of clarity boils down to three things: poor word choice, awkward phrasing, and the absence of information. The objective of a sentence is to convey to the reader what’s happening. If you’re violating any of these rules, you’re not clearly stating what’s happening. So let’s go back to John shooting Frank. In this version, John’s gun will be in his belt.

John gesticulates his leg to get his gun loose…

This is a classic example of poor word choice. “Gesticulates.” Hmmm… I guess that kind of works? But is it really the best verb to use in this situation? As is the case with all of these examples, I can handle one or two mistakes like this. The issue with clunky writing is that it’s never a couple mistakes. It’s an entire script filled with them.

John gesticulates his leg to get his gun loose and pummels Frank with a bullet.

Here’s where we get to poor phrasing. “…pummels Frank with a bullet.” Once again, I suppose this technically makes sense. But since the average person associates “pummeling” with something other than shooting a man, it forces the reader to stop, reread the sentence, and confirm the action, which is a flow killer. You never want anyone having to reread anything you’ve written. It should be clear the first time around.

Finally, let’s talk about absence of information. This is a HUGE one because many writers (especially beginners) assume that they’re conveying more information than they are. By leaving out the slightest detail or action, a clear sentence can become confusing, or worse, confounding. Let’s say you’re writing a car chase – one of the most famous ever – the semi truck vs. motorbike scene in Terminator 2. Imagine reading a paragraph like this one…

Terminator and John look back at the semi-truck, closing in quickly. He lifts up the shotgun, aiming it squarely at the T-1000 and – BANG! – shoots!

Since you’ve all seen the movie, you know who lifts the shotgun. But imagine if this were at the script stage. A reader would see “He lifts up the shotgun,” and ask, “Who lifts up the shotgun? You’ve listed two people. It could be either one of them.” This mistake is due to absence of information and it happens ALL THE TIME. Make sure you’re reading each of your sentences from the reader’s point of view. Have you included every piece of information necessary to understand the action?

You’re probably saying, “Eh, Carson. Now you’re being picky.” Trust me. I’m not. Cause it’s never just one. Imagine a mistake like this on every page. Coupled with more misused words and more awkward phrasing. A promising script can turn into a 6:30pm drive home on the 405.

VOICE

Voice is the creative side of writing. And, in a way, it works at odds with with our last two elements. That’s because you can’t add creativity without compromising simplicity and clarity. So when it comes to voice, I want you to remember this rule: If it doesn’t make the read more enjoyable, don’t include it. Because that’s the point of voice – to take the words on the page and elevate them to a point where they’re more enjoyable to read.

So what is voice? Voice is the writer’s unique point of view conveyed via a clever phrase, the perfect description, a brilliant metaphor, mastery of vocabulary, an unexpected observation, an important detail, a funny analogy, and the overall style in which they write. Voice does not need to be flashy. It can be subtle. It can be casual. But to make it work, you must be comfortable with your voice. It has to be a natural extension of you. If you force it, the writing will reflect that, not unlike how a nerd looks when he tries to act cool.

Also – and I hope this is obvious – voice should never overwhelm the writing. Content should always be king. Voice is there to supplement the action, not supplant it. A lot of beginners will make this mistake. Let’s go to the master of voice for our next example. This is from Tarantino’s Hateful Eight…

Domergue, whose modus operandi is outrageous behavior and the disarming effect it has on opponents, can’t believe Marquis did what he did. She SCREAMS AT HIM…

When you look at this sentence, you see that it could’ve easily been: “Domergue can’t believe Marquis did what he did. She SCREAMS AT HIM.” But Tarantino loves to tell us about his characters. He loves to add detail wherever he can. So he gave us this minor segue about Domergue before getting back to business. If you were looking to add voice to our now infamous battle between John and Frank, it might read something like this…

John rips his gun off the counter and—

BANG!

Sends a round right between Frank’s eyes, so clean it takes a full three seconds for the blood to flow.

Not going to win an Oscar. But you can see it’s more creative than our original line: “John grabs his gun off the counter and shoots Frank in the head.” Also, note that there’s no end to voice. You can keep going if you want.

John rips his glock off the cheap laminate countertop and—

BANG!

Sends a round express delivery right between Frank’s digits, so clean the blood’s still trying to find its way out.

It’s up to you to decide how far you want to go. If you’re unsure how much is too much, I implore you to err on the side of Rule 1: Simplicity.

SKILL

This is where most writing falls apart. And no, I don’t mean you have to meet a certain skill level to write a good screenplay. But you must know your limitations. The cringiest scripts to read are the ones where the writer is at a level 5 and they’re attempting to write at level 10. Imagine a high school kid trying to write like Cormac McCarthy and you get the idea.

Here’s the good news. You don’t need to be a great writer to tell a great story. But you can ruin a great story by trying to be a great writer. If you’re not a wordsmith, if writing is difficult for you, if sentences read janky whenever you try and get fancy, stick with the first two principles of this formula: Simplicity and Clarity. Remember that the story is the star. If the story is good, you don’t need to dress up the writing too much. I just opened up Terminator 2 and it’s very basic writing. Cameron occasionally gets descriptive but, for the most part, he sticks to simplicity and clarity. So if you can pull those off, and your story’s awesome, you can write a great script.