Search Results for: F word

Today we’re going to talk about summer madness and all the shapes, colors, and sizes it comes in. With Fast and the Furious dropping their bi-annual supercharged nonsensical treatise of loyalty and family on an all-too-eager public this weekend, how could you NOT get excited about the summer box office? I know I am. For both the good and the bad. Here are the key projects I’ll be keeping an eye on…

Dunkirk

It’s hard to have much of an opinion on a Christopher Nolan movie before it’s released since he’s so darn secretive. But even the most hardened Nolan films will agree that this is a pivotal movie for Nolan. His last two movies (The Dark Knight Rises and Interstellar) were major messes, with progressively sloppier screenplays. Exploring another genre was a good idea. But now we’re getting details on the plot, which involves soldiers… running away? Hmmm… that doesn’t sound very active or heroic to me. I’ll see any Christopher Nolan movie. They’re events. But if this doesn’t work, the Nolan shrine may need to be placed in storage.

Thor: Ragnarok

Wow. Where the hell did this movie come from?! As if Marvel didn’t have enough success. They take their worst character, pair him with the Hulk, put him back where he came from (another planet) and all of a sudden this looks like the freshest coolest comic book movie out there. There’s a screenwriting lesson to be learned here. You need to play with ideas more when you come up with a concept. If you go the obvious route, you come up with Thor 1 & 2. They found the right combination of ideas with this one and, out of nowhere, it’s awesome. This is now one of my most anticipated movies!

King Arthur

This movie was supposedly shot, then reshot, then one half of that reshoot was reshot and then someone shot themselves for shooting it in the first place. You can tell when a studio movie had extensive reshoots cause that money then comes out of the special effects budget. I suspect the effects to King Arthur were outsourced to a guy in Korea with an Atari 2600. You know a movie is bad when you don’t even know what it’s about after the trailer. What is this about? I suppose they should get credit for giving us a fresh take on King Arthur. But it just goes to show that fresh takes are still gambles. You have one that worked out (Thor) and one that didn’t (King Arthur). It’s time to put that sword back in the rock.

It

If you’re anything like me, you’re skeptical about this new Hollywood benchmark that’s taken over the internet: Most trailer views in 24 hours. It seems to be the only thing that anybody cares about anymore. However, everyone knows that the studios pay for at least a portion of these views. So how seriously can we take them? “It” is the new record holder, with something like 250 million views. Regardless of my trailer view skepticism, the movie looks great, and their adaptation approach was very clever. This book can’t fit into a single movie. However, a trilogy would’ve been too much. To split it into the kids film and the adults film was a stroke of genius. And we all know how much I loved Andres Muscietti’s previous effort, Mama. So count me in!

Guardians 2

There is no franchise more tuned into what the public is looking for than this one. Guardians 2 has just the right blend of character, humor, action and Groot. And you can already tell that this film is more confident than its predecessor, a movie where director James Gunn admitted that he thought he might be making the next Pluto Nash. Guardians will probably win the summer box office prize, a prize it will, unfortunately, have to hand over to Star Wars at the end of the year.

Spiderman: Homecoming

I’m neutral on this one. It seems to me like they’re making a smart play though. You know that old saying, “When you try to please everybody, you please nobody?” That’s clearly what was going on in the last two Spiderman movies. They wanted so badly for everybody to like them that you could feel it permeating off the screen. With this new version, they’ve kinda said, “Let’s move away from that” and gone back to Spiderman’s roots, which are in high school. So they’re targeting a more specific demographic, the teenage crowd, and we’ll see how it works. I know I liked Cop Car (the director of that tiny film landed this job). And if there’s a lesson to be learned for screenwriters, that may be it. Make a small passion project and direct it yourself. Who the hell knows what might come of it?

The Fate of the Furious

I don’t care what you say about Fast and the Furious. It still has the best and most inventive set pieces in the action game. It beats out Mission Impossible, Bourne, and James Bond in that category. In fact, one of the most common notes I give on action specs is to be more inventive with your set pieces. Fast and the Furious had two cars dragging an apartment sized vault through the city streets. You need to do better with your set pieces if you want to compete. Now regarding this plot point of Dominic turning on his team. How probable is it that it’s part of a bigger plan to help his team? One thousand percent? One million?

Valerian

For super movie nerds, this is a project all of us have been following for awhile. Why? One answer: The Fifth Element. This was going to be what Luc Besson would’ve done with The Fifth Element had he had more money. Besson is a great filmmaker. And he was supposedly creating sequences and techniques that had never been used before to give the audience a one-of-a-kind experience with Valerian. But after seeing the trailer, I was shockingly disappointed. This was it?? Sure, it seemed okay. But it hardly felt like something I’ve never seen before. Then it struck me. It wasn’t the visuals I was having a negative reaction to. It was the characters. How fucking boring do these two characters look? They mumble. They have no chemistry. There doesn’t seem to be any conflict between them (in fact, it’s the opposite, they seem to like each other – major screenwriting mistake!). Watch the Guardians and Thor trailers then watch this. Note how much more personality the characters have in those trailers. Valerian is in trouble. And let this be a lesson to screenwriters everywhere. Don’t get lost in your world-building. Make sure the characters are compelling first. Or nothing else matters.

Alien: Covenant

Why do I get the feeling that Scott’s only making these movies out of spite? And when Scott goes spite, he goes FULL SPITE! After this film, he has three more Alien movies lined up. Say what?? Not to jump on Thor’s jock yet again. But the idea with any franchise is to elevate, find fresh new ways to explore the subject matter. This looks like the same exact movie as the last one. I don’t get it.

Rest of the movies: I’m not a fan of the DC films so I’m not looking forward to Justice League or Wonder Woman. It seems that their big mistake is hiring visual directors, whereas the Marvel guys are hiring storytellers. As for “maybe” movies – Pirates, The Mummy, and Apes – the reinvigorated Pirates looks like it’ll be the breakout (can Disney do no wrong?). But The Mummy doesn’t look bad either. Don’t get me started on Transformers (they could slip one of the previous four films in theaters, slap a “5” on it, and I swear nobody would notice. Save 200 million bucks). One day somebody’s going to do a documentary on how the five worst movies ever made became five of the biggest box offices successes of all time. Of the two Stephen King offerings, The Dark Tower was never my cup of tea. “It” was so inspired. Tower just dragged on. I never made it to the end (8 books!), but I hear the ending was terrible. All that investment for no payoff. I have a feeling this franchise isn’t going work. Still, one for two ain’t bad.

And that’s my roundup! What about you folks? What are you looking forward to? What movies do you think are undervalued? Overvalued? Chime in in the comments!

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from Black List) A precocious young writer becomes involved with her high school creative writing teacher in a dark coming- of-age drama that examines the blurred lines of emotional connectivity between professor and protégé, child and adult.

About: If you weren’t paying attention, you may have missed Jade Bartlett’s script, which appeared near the bottom of last year’s Black List. Bartlett started as a playwright and occasionally acts, grabbing a bit part in last year’s, The Accountant. She’s looking to direct Miller’s Girl as well.

Writer: Jade Bartlett

Details: 121 pages

One of the things I’ve been struggling with lately is the balance between reality and cinematic license. Movies are a heightened version of reality and are therefore subject to a different set of rules than real life. A common example is that old movie setup of the directionless loser grabbing the attention of the hottest girl in town. Sometimes audiences just go with that stuff.

But I don’t see this as an excuse to completely ignore reality. Storytelling is still subject to suspension of disbelief. If your characters start doing or saying things that are too far removed from the realm of believability, the reader/audience will feel the writer’s hand, pull out of the story, and begin to observe it from the outside as opposed to where they should be observing it, which is from inside.

For example, I was originally going to review a script called “Coffee and Kareem” today, another Black List script about a 9 year old boy who teams up with a cop to take down a drug lord. It starts off funny, but at a certain point, the boy is joking about extremely advanced sexual situations that there’s no way a 9 year old boy would a) know about or b) care about. I’m talking: “As I suck the meat off yo clit, won’t stop till ya squirt” level situations. The writer went too far off reality’s path and the suspension of disbelief was broken.

Miller’s Girl never goes that far. But the script is a strange one, skirting that line so sharply that it was hard to take what I was reading seriously all the time. With that said, Bartlett’s unique voice and almost magical mastery of the English language ensures that Miller’s Girl is a rewarding experience.

Awkwardly pretty Cairo is a gifted 17 year-old writer. Her new high school creative writing teacher, Jonathan Miller, used to be a writer, but has since regressed to the point where he hasn’t written a word in years, hiding behind his teaching job as the reason he no longer pursues the craft.

Miller immediately recognizes how talented Cairo is, and the two start hanging out with one another after class, trading the occasional quote and seeing how long they can quip each other before someone says, “touche.” Needless to say, Cairo starts to become fascinated with Miller, and looks for more opportunities to spend time with him.

Meanwhile, Miller’s best friend and fellow teacher, Boris, has his eye on Cairo’s best friend, the gorgeous Winnie. Whereas Cairo is cerebral, Winnie is all about the physicality. And when she picks up on Boris’s interest in her, she milks it for every ounce it’s worth, basically broadcasting that he can fuck her any time he wants.

Things get complicated when Jonathan assigns Cairo to write a short story and Cairo writes up a Hustler article about a teacher who seduces a student. Horrified, Jonathan tells Cairo to destroy the story and reminds her that they are only friends. Feeling rejected, Cairo instead gives the story to the principal, resulting in a series of events that may destroy Jonathan’s career, and with it, his life.

First of all, there is no doubt that Bartlett is a gifted writer. I mean, when you read this, you will immediately notice the limitations of your own intellect. The woman is a wordsmith who has few equals.

But here’s what I mean about reality. Most of the conversations here, particularly the ones in the first half of the script, reek of a writer showing off her skills rather than one who’s trying to write the best story.

There are a lot of lines like this one: ”Can you keep a secret?” “I’m keeping Victoria’s in my pants. Does that count?” And while, on their own, these lines are harmless, when they’re strung together with 50 other variations of the same exchange, they stop feeling like real people and start feeling like, “Check out my dialogue skills, bitches.”

On top of that, there are moments where both our male teachers and 17 year old female students are hanging out before class and Boris will say to the girls something like, “So did you get laid last night?” I know I haven’t been in high school for awhile. But doesn’t that kind of question get you fired these days? When people say and do things that aren’t realistic, it’s inevitable that the reader will be pulled out of the story.

After I finished the script, I found out that Bartlett is also a playwright, and that made sense. I know dialogue is a big focus in playwrighting and that the idea is to go bigger and snappier. So maybe that explains some of the more outrageous dialogue. But in screenwriting, you have to watch out for that.

And, see, that’s the thing. When this script got really good is when it dropped the pretense and focused on the conflict. The best scene in the script happens on page 74 when Jonathan confronts Cairo about her short story.

Gone are the quips, replaced by a genuinely intense conversation. Every word matters. If Jonathan isn’t clear to Cairo that there’s nothing between them, he could get in some deep shit. But if he goes at her too hard, she could get upset and fuck him over anyway. So it’s a very delicate balancing act that goes to show – genuine conflict and drama is always better than trying to force something out of nothing. If you go into a scene without clearly understood directives from both characters, you’re going to be flailing around like a fish, inevitably trying to dress up a body that isn’t there.

It shouldn’t be a surprise, then, that that’s when Miller’s Girl really picked up. Things get dark fast and this script leaves you with a number of feelings – anger, frustration, confusion – that you don’t typically get from a read. Whereas Bartlett struggles to keep things truthful, she excels at coming up with situations that there are no simple answers for.

The hardest scene for me to read was Jonathan’s scene with his bitch wife after he’s been suspended. Holy shit was that intense.

If the same sort of truth and genuine conflict used in that scene could’ve been used throughout the first half of the script, this would’ve gotten an “impressive.” Still, while flawed, it’s a script that stays with you. And we all know how rare that is to find.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Playwrights moving to screenwriting – You have to expand your scope. While reading this, I didn’t get any sense of the school at all. This is likely because, as a playwright, you don’t have to worry about those things. But as a screenwriter, even though your focus will be on a handful of characters, you want to bring more of your surroundings in. We need to see other classes, meet other students, feel like there’s a real world to explore here. When your scope is too narrow, something will feel off about the story that the reader can’t articulate. That’s usually it. Bring in the rest of your world and the problem will be solved.

What I learned 2: The word “vituperation,” which means “bitter and abusive language.” I have never, in the 7000 scripts I’ve read, come across that word before. Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to casually drop the word “vituperation” into conversation today and not get called on it. Let us know how it went in the comments!

Genre: Fantasy

Logline (from writer): A team of Victorian monster hunters must save the universe from their biggest threat yet, themselves.

Why You Should Read (from writer): I’m a Benihana chef, mandolin player and a broke as a joke screenwriter living in LA now for two months shy of a year and I’ve written about 10 screenplays. I’ve got about thirty dollars in my bank account so there’s not much there to submit this screenplay to a formal contest which sucks, but I’m living the dream…which is cool. It would be very helpful if you would review it so I could know if I was heading in the right direction and if my diet of peanut butter jelly sandwiches in front of my computer monitor is paying off.

Writer: Kathryn Whipple

Details: 106 pages

Okay, before we get to the script, let’s talk about this logline. I’ve been reading lots of loglines for the shorts contest and it continues to be a destination of disaster for aspiring writers.

Everything about this logline works until you get to the word, “from.” “…from their biggest threat yet, themselves.” The best way to describe that ending is that it doesn’t clarify what the movie is about. And what did we just talk about yesterday? Making sure the concept is clear!

Now, after reading the script, the logline does, in fact, make sense. But that’s the problem. It only makes sense AFTER you’ve read it. The point of a logline is to tell us what the script is about BEFORE we read it.

In this case, “themselves” refers to our protagonists’ doppelgangers, who travel through a rift and try to kill our heroes. So, we need to clarify that in the logline. Therefore, the logline should look more like this:

A team of Victorian monster hunters must battle a group of doppelgangers who invade our planet on a mission to destroy our universe.

Now, the question is: Is that premise any good? That’s something I’ll answer after the plot summary. But the point is, that’s the real premise you’re working with, so you have to be honest about it and include it in the logline. You can’t be coy.

England. 1850. It’s the Victorian era. Reason to be optimistic. Except for the monsters that keep popping up through inter-dimensional portholes threatening to kill everyone. If only there was someone to combat these monsters.

That’s where our team comes in. There’s the gorgeous Baroness Whitetower, our de facto leader, the monster-fighter on the rise, Victoria, and finally the always serious, Gunner, who doesn’t get rattled no matter how big the monsters get.

These guys can easily take out a 150 foot caterpillar in a couple of hours. But here’s where things get tricky. They don’t want to kill these monsters. They want to send them back where they came from. This requires a complicated method of creating a rift in the space-time continuum and pushing them back through that rift so they can go back to their parallel world of origin.

All of this is going gorgeously until the police arrest the Baroness for all the destruction she’s caused around town (they have no idea what this destruction was in service to, of course). That’s followed by a new rift opening and – get this – the EVIL REPLICA versions of our monster killing crew arriving.

These folks aren’t nearly as friendly, and inform us that they’re here to destroy our universe because if they don’t, the universes will start collapsing in on each other.

The doppelgängers bring with them many rifts from many different universes, all spewing about fresh monsters of every conceivable disposition, making our crew’s mission of taking out their doubles all the harder. Will they do it? Or is our universe doomed for collapse?

So this is what I was getting at earlier. On the one hand, you have a team of Victorian monster hunters hunting monsters. That’s pretty cool, right? However, halfway into Rift, that isn’t what our script is about. It’s now about a group of evil doppelgängers using the rift-system to travel to parallel universes and extinguish them.

That’s not a bad idea. But it’s not really what we were promised, was it? You could argue that our doppelgängers do open up rifts from which new monsters do arrive and must be fought off. But, ya see, by adding the doppelgänger element, you’re essentially doubling up your concept. You now have two concepts competing for the same movie…

Concept 1: Victorian monster hunters taking on monsters.

Concept 2: Space-time continuum protectors who must fight their parallel universe doubles.

The reader’s like, “Wait, which movie am I watching here?”

Luckily, the solution to this is rather simple. Drop the doppelgänger element. You can still have someone come through the rift and threaten our group, but make him a normal villain, not a double. That way the focus can be squarely on the monster element, which is the bigger sell here.

As for the script itself, I thought the execution was okay, if a little scattered. In the attempt to add character depth, we lost sight of prize. Case in point, when Whitetower gets back from the opening monster battle, she’s greeted with a 16 year-old nephew she didn’t know she had.

This nephew, Everett, is hers through her dead sister’s husband, Cal, a man we just met moments ago once we arrived home, who also seems surprised to learn he has a nephew.

I don’t know about you, but why would I care about the nephew of the main character’s brother’s dead wife, a man who wasn’t even important enough to be on the opening monster killing mission? It was an odd character to spend so much time working into the story.

Speaking of, there wasn’t that one character who stood out. That wasn’t through lack of trying, but I almost felt like more of a “hero’s journey” approach was needed here, where you bring in a “chosen one.”

Instead of having Victoria be a well-established member of the crew, why not make HER the “Everett” of the bunch. Whitetower and their crew get home after the opening battle and Victoria, reimagined as a nervous 18 year-old, is waiting on the doorstep. And instead of making her someone’s cousins’s brother’s half-sibling’s son, make it simple: she’s Whitetower’s daughter.

She’s then taught the ropes and becomes an integral part of taking down the Rift-jumping evil villain. That’d be how I’d approach it, anyway.

Finally, I thought the second act was too short. I consider the beginning of the third act to be the opening up of all the rifts with all the monsters needing to be fought off, and that comes at the midpoint of the script, giving us 55 pages of battle. That’s too long.

The better approach would’ve been to have a single rift open up at the midpoint with a rather nasty monster that they’ve never seen before needing to be killed, and then the threat of multiple rifts opening later on, which would happen at the end of the second act, leaving the entire third act to be our “one giant battle.”

The big takeaway here, though, is that this concept’s strength is its monsters, not its doppelgängers. So that’s where I’d focus the story if I were Kathryn.

Screenplay link: Rift

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Unnecessarily complicated familial ties having major story implications is always a lose-lose. If you’re going to bring a major character into the story, try to make the familial connection as straight-forward as possible. A son. A daughter. No half-nephews or twice-removed uncles. I suppose if Cal was the main character here, Everett would make more sense. But Cal is some afterthought who wasn’t even on the original mission. So he feels as peripheral as peripheral gets.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A steamboat captain is recruited by a British ivory company stationed in Northern Africa to find one of its men who’s lost in the jungle.

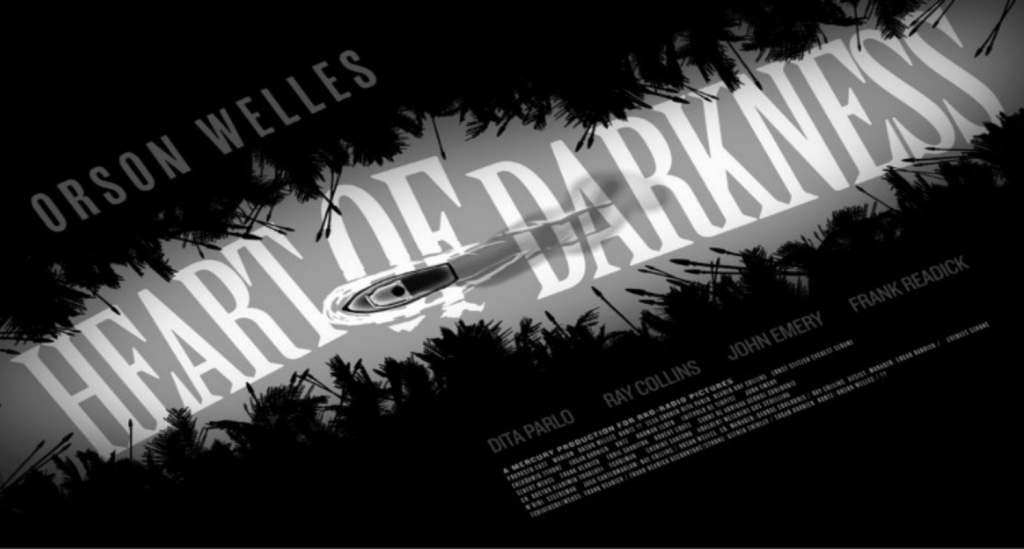

About: Best known for tricking radio listeners into thinking the earth was under attack by aliens from Mars, and for creating the “best film ever made” in Citizen Kane, Orson Welles is also known as the poster child for lost opportunity. His choice to make a movie about one of the most famous newspaper magnates ever to live (Randolph Hearst) during a time when newspapers were so powerful, they shaped our very reality, Hearst, who knew every bigwig in Hollywood, demanded Welles not be able to make any more movies. And that’s pretty much what happened, with Welles only trickling out a handful of films during his career. Heart of Darkness was a casualty of this blackballing, and a movie Hearst desperately wanted to make.

Writer: Orson Welles (based on the novel by Joseph Conrad)

Details: 185 pages

In one of the most famous movies never made, Orson Welles had plans to be the first filmmaker ever to shoot an entire movie from the main character’s POV. While this is merely an artistic choice today, back then, with the weight of the cameras and how difficult it was to set up even a basic still shot, the process for filming a 2 and a half hour POV movie would’ve been an almost impossible undertaking, which is at least partly why this movie never got made.

It should be no surprise that Welles wanted to tell this story. The dude is dark. He routinely spat out quotes like this one during his life: “We’re born alone, we live alone, we die alone. Only through our love and friendship can we create the illusion for the moment that we’re not alone.” Holy barnacles, batman. Someone please check the going rate on nooses on Amazon.

Heart of Darkness starts out, rather amusingly, with Orson Welles staring at us while we’re lodged inside a bird cage. He then tells us, the audience, that in this film, we’ll be seeing the movie through the main character’s eyes. He then shoots us, killing the bird version of ourselves, to show us just how powerful this device will be.

Then, even more amusingly, as if he didn’t think that would be enough to convey just how outrageous this first person approach will be, he places us in the shoes of a prisoner, then walks us to an electric chair and executes us. If we hadn’t understood the device that would be guiding us through the movie before, we did now.

That leads us to Marlow, our main character, who also happens to be us. We’ll be experiencing the movie through Marlow’s eyes. Marlow is an American steamboat captain who’s been tasked to go to Northern Africa to find a missing member of “The Company,” that being an ivory trading company based out of Britain.

The missing person is the mysterious Kurtz, who’s so elusive we’re not even sure what he does. Kurtz is located deep in the jungle, up one of thousands of river tributaries, at a remote station where he’s pulling in more ivory than the rest of the company combined. But Kurtz hasn’t written the company in awhile, and people are getting worried.

So Marlow, or “us,” team up with Kurtz’s beautiful and flirty fiancé, Elsa, to find this man that nobody can stop talking about. The further inward they go, the clearer it is that this place is hell on earth, a breeding ground for disease and death. The few who somehow escape these scenarios, often end up crazy. That, they fear, is what’s happened to Kurtz, and if we don’t find him soon, what may happen to us.

Welles wrote this script when he was 25 years old, and it feels like it. Those early 20s scripts are always the most ambitious as you want to change the world and redefine the medium. You’ll throw in any and every weirdness you can just to stand out. Who cares if it serves the story. As long as it gets people talking!!

With that said, if there’s anyone who’s capable of getting away with that, it’s Orson Welles. Every choice he made in Citizen Kane, someone told him he couldn’t do it and he did it regardless. Greatness is never born out of someone saying, “I want to do this exactly the same way everyone else has done it.” So there’s something to be said for Welles’ gung-ho attitude here. And, in his defense, the subject matter warrants taking chances.

But the first person perspective, while cool in theory, presents several storytelling problems. And the mistakes made from scripts like this one, as well as its cohorts that eventually made it to the screen, only to quickly be forgotten, are likely what inspired the first generation of screenwriting professors to say, “Maybe doing it this way doesn’t work.”

What’s one of the first things they teach you in Screenwriting School? The main character needs to be active. Why does the main character need to be active? Because active characters drive stories and because audiences like people who DO things as opposed to people who REACT to things.

And that’s pretty much all Marlow does, is react. In fact, the entire movie consists of him watching OTHER PEOPLE do things. True, he is the captain, so he is taking our characters to Kurtz. But there’s never a situation where Marlow is like, “We need to go that way!” And he runs to the steamboat room and starts pouring on more coal before running out and pulling a rare Fast And Furious’esque figure-8 steamboat move to barely make it into the Katonka River.

It’s more like, someone will come up to him and say, “Hey, how you feeling?” And Marlow will say, “All right. I wonder what the weather is like back home.” There are a lot of interactions like that, giving us a character dominated by a whole lot of inactivity.

It’s not a total bust though. Heart of Darkness conveys just how popular build-up can be. If you build something up enough, the audience WILL stick around until that thing arrives. I don’t think I’ve ever heard one thing (the name “Kurtz”) mentioned so many damn times in a single script.

Every other word out of someone’s freaking mouth was “Kurtz,” to the point where even though I was bored to tears because nothing else was freaking going on, I wanted to find this Kurtz fellow! I mean, with so many people talking about him, he had to be worth the wait, right?

What I also found interesting was that despite this novel being written over 100 years ago, that even back THEN they were still using love triangles. I say that because you think of a love triangle as a cheap literary device used to stir up some artificial conflict. But the magnetic and flirtatious Elsa working her magic on Marlow while her fiance, Kurtz, draws closer every minute, was of the more dramatically compelling storylines in the script!

The weird thing, though, is that the very thing I found gimmicky at first – Welles’s cheesy masturbatory opening sequences – was exactly what I craved more of as we made it past the century page mark. The script gets so bogged down in its dark subject matter and relentless attention to camera detail (seriously, the word “CAMERA” was easily used over 600 times in this script), that there wasn’t any fun left. Add on a protagonist who just watches everyone else do things without doing anything himself and you can see why something like this would get boring quickly.

The only thing to keep our interest was that damn Kurtz. But because, at a certain point, that’s all the story had to offer, even I had to dive into the water and swim back to shore. This would’ve been an interesting experiment had it ever been produced, but very likely a failed one. That’s exactly what the studio head said to Welles at the time. And do you know what Welles came back with? “No problem. I have another idea. It’s called Citizen Kane.”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You are not as clever as you think you are. When you think that you’re rewriting the cinematic language by talking directly to the reader or going first person POV for an entire script? Know that there was a script written as far back as SEVENTY SEVEN YEARS AGO that was doing the same thing. When it comes to screenwriting, choose the most compelling story you can write over writing something gimmicky with tons of bells and whistles. If Orson Welles couldn’t pull it off, you probably can’t either.

Genre: Dark Drama

Premise: When a young girl named Allison Adams goes missing, four other women named Allison Adams find themselves at first peripherally, and then directly, pulled into the mysterious disappearance.

About: Allison Adams made this past year’s Black List, was written by actor Devon Graye, and is really fucked up. Now, you may ask how anyone could write something so fucked up. Seems like a good time to throw this nugget at you: Graye played Teenage Dexter on the serial killer show, Dexter, for a year. I’m guessing much of what he was exposed to there inspired this screenplay.

Writer: Devon Graye

Details: 92 pages

If there’s an argument to be made against structure and screenwriting convention, “Allison Adams” is a script you’d file as evidence in the trial. It throws the conventional whodunnit out the window, adds some Fargo’esque wallpaper to the living room, then dives into the basement where guys like Thomas Harris, David Fincher, and Patrick Bateman are playing poker.

Before we even get to the script, I want to hammer this point home. I read a lot of “missing girls” screenplays. Heck, there’s a whole cottage industry of missing girls novels. It is one of the most oft-used setups in fiction. And it works because there’s nothing that triggers readers like a helpless girl being taken.

Now you’d think that the average writer would know, when there’s concept competition, you have to bring originality to the table or nobody’s going to give a shit about your script. The default setup for this concept = small town, girl goes missing, meet all the suspects.

And yet, most of what I read in this genre is right off the assembly line. While they all have their slight variations that the writers will tell you is what makes them “fresh takes,” the truth is they’re all the same.

Allison Adams is not only NOT an assembly line script. It was crafted in some 1970s Russian basement by a guy named Lukslava.

In a small town, a young girl named Allison Adams goes out to ride her bike and never makes it home. As the town comes together to try and find her, we meet several women, all of whom, strangely, are named Allison Adams.

Nurse Allison has a 5 year-old son who she’s struggling to take care of due to the immense stress of her job. 16 year-old Cheerleader Allison is preparing to lose her virginity to her dream boy, Michael. However, she secretly has a thing for a 40 year-old neighbor who she could swear flirts with her whenever they talk.

Next up is Diner Allison, whose been saving up to buy a boat and sail around the world when she turns 50, which is later this year. And finally there’s 68 year-old Hermit Allison, who stays within the confines of her house as she has a rare condition that makes it impossible to make choices.

The script bounces around to the four Allisons, who at first seem to have nothing to do with the disappearance. But then a creepy thin man straight out of a Stephen King novel starts showing up in their lives. He starts with Nurse Allison, arriving at her hospital with a bottle of orange liquid he claims is his blood-soaked urine. But when Nurse Allison goes to get the doctor, the creepy-as-F dude disappears.

Eventually, the Thin Man starts killing off the Allisons, and it’s a race from the understaffed local police force to stop them from taking each Allison down. But why is there this obsession with getting rid of Allisons in the first place? The answer lies in the fact that each Allison is way more complex than we know.

Reads like this usually go in a predictable pattern for me. At first, I love them. They start out so damn mysterious, like when you pour yourself a bowl of Fruity Pebbles and somehow a cocoa puff makes it in there. There are all these unanswered questions. And the creepy weirdness makes every page feel like the possibilities for the story are endless.

Then once the script hits the second act, the writer realizes the narrative needs to go somewhere, and the script struggles to keep its weirdness while introducing logic into the mix. Once the script hits the final act, and the writer has to actually wrap things up, everything falls apart as it’s exposed that the writer never had a plan in the first place. They wrote themselves into a corner of mysteries and bet on black they could write their way out. 99% time, they don’t make it out, dying an elongated death of screenwriting starvation, the last words typed on their screen a combination of an idea for a scene in the third act that involves a wheelchair, and half their grocery list.

So Allison Adams should be commended for being a member of the 1%. I’m not going to get into how Graye did this, as that would unleash massive Spoiloria. But we’ll just say this: He did it.

To those who like weirdness and hate Hollywood structure, Allison Adams is a reminder that you can be weird as long as you have a plan. Do not start writing a weird story with no idea where you’re going. I guarantee you, your script will be a mess. You don’t have to know your ending exactly. But you should have a good approximation of it.

How do I know Devon planned this whole story out ahead of time? Cause there were about 30 payoffs in the third act. That’s the easiest way to figure out if the writer had a plan. If they’re paying off things that happened on page 20, page 34, page 51, you know they had a plan all along. And the script is always better for it.

Writers who don’t have a plan overcompensate with the third act, injecting all this crazy wild stuff in the hopes that it will distract the reader from the fact that you ended up here just as cluelessly as they did. Crazy wild over-the-top stuff = made it up. Tons of payoffs = planned.

The script is not perfect, although these weird scripts rarely are. That’s the beauty of them. The big weakness is the character of Diner Allison. Whereas all the other Allisons had something weird going on, Diner Allison was just a good old girl with a dream.

Look.

If you’re going to go the non-traditional route of following multiple protagonists, that’s fine. But don’t just have multiple protagonists to have them. Make sure each of them merit their inclusion.

Because often what a writer will do is they’ll get this story point set in their head. In this case: “I’m going to have four Allisons.” And even though, five months down the road, one of those Allisons isn’t working, they’ve always been so set on having four Allisons that they’d rather keep the thing that’s not working than move off their original idea. You guys know what I’m talking about and you know what you have to do when this situation arises (if not, see “what I learned” below).

But other than that, this was a weird suspenseful ride that reminded me you can play with generic setups as long as you find a truly different way to explore them.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: KILL. YOUR. BABIES. OR. MAKE. THEM. ADULTS. No matter how much you love the idea of something in your script – a plot point, a scene, a character – If it’s not working, you have to kill it. Or, if you don’t want to kill it, you have to try something else to save it. Diner Allison is the weak link in this script. She either needed to be dropped or reimagined into something as interesting as the other characters. Making these choices is never easy. But if you ignore them, your script suffers for it.