Search Results for: F word

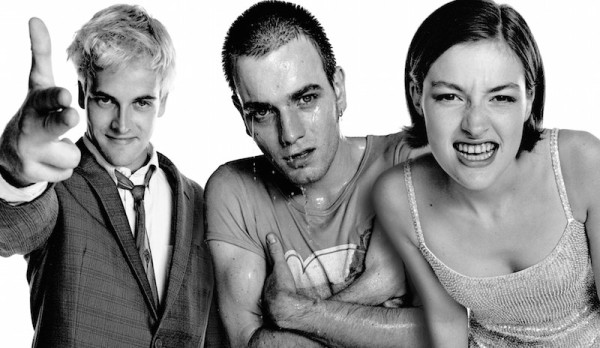

A surprisingly kick-ass movie about friendship that was almost as fun to watch as the original!

Genre: Drama

Premise: 20 years after Renton abandoned his heroin-junky friends for a drug-free existence, he comes back into town to try and make things right again.

About: The original Trainspotting launched the careers of director Danny Boyle and Ewan McGregor. But when Boyle went Hollywood, choosing Leonardo DiCaprio to star in The Beach after promising the role to McGregor, it destroyed the friendship instantly, which is the reason why it’s taken 20 years to make this film. Ironically, T2 is a film about mending broken friendships.

Writer: John Hodge (based on the novel by Irvine Welsh)

The original Trainspotting was part of a revolution in screenwriting and filmmaking that rocked the 90s. Writers and directors were sick of how studios had turned the business into a mathematical formula, and visionaries like Tarantino, Stone, Rodriquez and Boyle were more than eager to bulldoze that formula and erect an aggressive anti-structure in its stead.

Some say that’s the last time Hollywood took chances. After “indie” went mainstream, every potential product had to hit pre-determined checkmarks to get a green light. That’s changing, with Netflix giving directors huge budgets to do whatever they want.

But that hasn’t resulted in the kinds of voices we got back then. Even when a popular filmmaker does make some noise (Cary Fukunaga – Beasts of No Nation), a clear voice doesn’t come with it. In other words, I don’t think you’d know you were watching a Cary Fukanaga film unless someone told you you were.

That was the great thing about writing and directing in the 90s. People were trying to distinguish themselves and stand out. Let’s see if Boyle still has the desire to innovate, or if he’s simply been hit by the nostalgia bug.

When we last heard from Renton (Ewan McGregor), he’d ditched town to find a better life. Well, maybe he found that life and maybe he didn’t, but 20 years later, we see him flying back into town to give his best friend, Simon, the money he stole from him before he left.

Simon is attempting to turn his bar into an upscale brothel and asks Renton if he’ll help. Renton’s not interested but things are bad enough back home that he decides, what the fuck? I’ll stay for awhile. Renton also reconnects with his other best friend, Spud, just before Spud commits suicide. For 20 years, Spud still hasn’t kicked his heroin habit, and he’s ready for one final glorious high.

Renton convinces Spud to choose life, and recruits him to help on the brothel project. What they don’t know is that Begbie, who’s like a bar-hopping Scottish Hitler, as well as someone Renton fucked over 20 years ago, has just escaped prison. And when he finds out that Renton is back in town, he vows to find him and put him six feet under.

I’ll tell you what my big worry was going into Trainspotting 2. And it’s something that all screenwriters should be aware of. I thought Boyle was using this movie as an excuse to work with these actors again.

Why is that bad? Well, the best movies come when you’re passionate about telling a story. That’s how the original Trainspotting was born. Boyle read the book on a plane and he just had to make it his next film.

Once you start writing scripts for reasons other than wanting to tell an amazing story, that’s when you get in trouble. That’s not to say you can’t write something good unless you come at it that way. It’s just less likely to happen. And through the first 30 minutes, that’s what I thought had happened with T2. The over-reliance on nods to the previous film was the tip-off.

But then something happened. After we set up the rather convoluted plot, we were able to focus on these characters’ personal journeys as well as the film’s theme, and that’s where the movie began to shine.

You see, you may think that the reason the original Trainspotting is still relevant today is because it was flashy and bold and had a great soundtrack. But the reason Trainspotting lives on while similar flashy movies at the time (Natural Born Killers) have faded from memory, is because it had something to say about the world. Its theme was slammed into our faces throughout the film’s 2 hour running time: CHOOSE LIFE.

And Trainspotting 2 follows in those sprinting footsteps. Its theme is that while life takes you in different directions, and you get older and things don’t pan out the way you planned them, the one constant you always have is your friends. They’ll be there to pick you up. And that’s why Trainspotting 2 isn’t just another nostalgia trip. It actually has a reason for existing.

And if I’m going to leave you with anything to think about today, it would be that. The script you’re working on now? What are you trying to say with it? What do you hope people leave with when it’s over? If you’re just hoping they have a chuckle or that they enjoyed some cool action scenes, you’re not doing your job. If people want a fun ride, they can go to fucking Disney Land. They come to movies because they want to feel something.

And while I will always preach that entertainment comes first, if you want a story to stay with someone, you have to say something about the world, about people, or about our plight as a species in it.

The most powerful moment in this film was when Renton is asked, “What’s Choose Life?” The catch-phrase that became the marketing voice over for the original trailer. And Renton goes on a modern day “Choose Life” rant that resonates so hard, I found myself squirming in my seat (it’s much longer than in the trailer). You’re asking yourself, “Am I this person? And if I am, why the fuck am I allowing that to happen??”

I don’t know. I feel like writers are afraid to challenge audiences like that these days. Or when they do, they do it all wrong, like Moonlight or Machester by the Sea, where they bury their messages under layers of melodrama and overwrought unimaginative dialogue.

That was always the genius of Trainspotting: it could make you go from crying to laughing within a millisecond. They didn’t lose that here (don’t believe me? wait til you guys see the Spud suicide attempt).

I expected this movie to be a time-waster. It was more a wake-up call to remind me what good scripts are capable of.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Passion comes through on the page. When you’re passionate about something, the reader feels it (and when you aren’t, THEY FEEL IT EVEN MORE!). For that reason, write about things you feel passionate about at this moment in your lives – passionate good, passionate bad – it doesn’t matter. As long as it’s gnawing at you, it will come through on the page. Trainspotting was constructed around this idea of mending broken friendships, which is what Boyle and McGregor had to do to work together again. And it’s for that reason that everything here feels so authentic and truthful. If these guys were just going down Memberberry Lane, this film would’ve sucked.

Occasionally in the comments section, a debate will pop up about well-loved scripts that “aren’t movies.” They’re just really good scripts. For the aspiring screenwriter, a debate like this is confusing. What’s the difference? How is it possible to write a good script that would be a bad movie?

I always get anxious during this argument. It takes so much to write a good anything that if you’re restricting yourself in any one area, you’re making an already difficult task even more difficult. The last thing we need is some writer getting traction on a script but believing he’s a failure because, “It’s not a good movie.”

However, I have to admit that there’s something to the argument. There are certain scripts you will write which read well but are doomed on the big screen. Luckily for you, I’m going to tell you what those scripts are, so that even if you decide to write one, you at least know what you’re getting into. And keep in mind that writing a “great script that’s not a great movie” isn’t the worst thing in the world. It’s gotten a lot of screenwriters their start in this business.

For ease-of-writing purposes, I’ll be referring to the great script that’s not a great movie as an NGM (not great movie) from here on forward.

NO GENRE

The first NGM script is the one without a genre. When you don’t have a genre, you have a film that studios don’t know how to market, and by association, a film that’s not technically a “movie.” The most recent example of this is Passengers. Passengers was known as the best unmade script for a decade. However, once it came out, audiences were like, “Huh?” Is this a sci-fi film like Aliens? No. Is this a love story like Titanic? Not exactly. Is it a comedy? Sort of. Is it a drama? Sometimes. All of these problems were less evident when you were reading it but became enormous once you were making and marketing it. Every once in a blue moon, no-genre scripts will turn into something amazing (Pulp Fiction, Being John Malkovich) but it’s rare enough that it’s like trying to win the lottery. When you stay in the master movie genres (Horror, Action, Thriller, Sci-fi, Comedy) you’re writing a script that’s clearly a movie. Even the less glamorous genres (Drama, Period Piece, Western, Romantic Comedy, Serial Killer) will work. But when you can’t place your script into any known genre, you’re probably writing an NGM.

STILL

On the page, “still” doesn’t matter. The reading experience is a static one (you’re sitting down staring at words) so you don’t care as much if the characters and action are still as well. To this end, you can write some pretty good “still” stories. But these scripts will come crashing down once they reach the big screen because, all of a sudden, you’re asking your audience to sit down for 2 hours and watch ZERO movement. “Movies” are synonymous with “movement” so if you don’t have any, you’re going to witness a rapidly borified audience. My introduction into this was Everything Must Go, my favorite script at one time, about a guy who’d been kicked out of his house by his wife and decided to set up a room on his front lawn and continue living there. I loved that script. But once it got to the big screen, all I saw was a man sitting down for two hours. The entire story collapsed. If you’re into “still,” I recommend writing a novel. If you’re writing a movie script, however, make sure your characters are moving towards something, literally. That doesn’t mean you have to write Bad Boys 3. An investigation where the hero is walking from one new clue to the next is fine. But ixnay on the don’t-move-aye.

CHARACTER-DRIVEN (or “TALKING HEADS”) SCREENPLAYS

Every good script should be character driven on some level. But if that’s the ONLY thing going on in your script? If there’s no heightened concept or flashy plot points? You’re probably writing a novel or a TV show, not a movie. A perfect example is a movie like 2010’s “The Kids Are All Right,” or even last year’s “Manchester By The Sea.” These scripts read well (I mean, I hated the Manchester script, but a lot of people liked it). But once they reached the big screen, you’re just watching a lot of talking heads expound emotion. And that’s not good enough for the big screen anymore. People are used to showing up to the theater and seeing 300 million dollar visual spectacles. Two hours of people looking bummed out doesn’t work. The Kids Are All Right is an interesting case because it’s got more of a story to it, but that movie had to be freaking PERFECT just to squeak into the bottom level of the public consciousness. If you’re writing stritcly character driven movies, you may want to move over to TV.

The flip side argument of all this is that there are certain “horrible” scripts that are great movies. The nature of what makes them great onscreen is what hurts them on the page. For example, the Pirates of the Caribbean movies are drowning in plot, have a ton of characters, and contain a bunch of cool effects that you can’t see on the page. All these things make them boring reads but “cool” movies. Or a script like La La Land. That movie IS the musical numbers, which you can’t see on the page.

I would agree with all of this up to a certain point. If you’re writing within the system (you’re getting paid to write by the studio), than it’s more important to make your bosses happy than write a script that pleases the masses. But if you’re writing on spec, I’m sorry but you’ve got to pull off both. You’ve got to write something that’s going to work on screen AND on the page. And that’s totally possible.

I hope this helps when choosing which script to write next. Please share your own NGM examples in the comments section in case I missed anything!

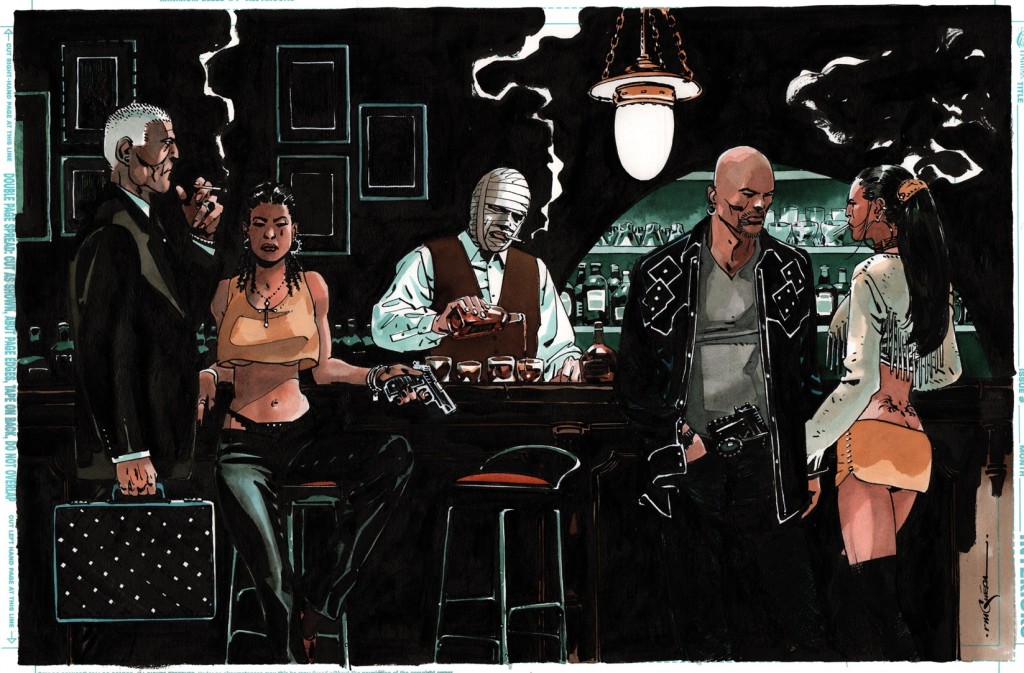

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama

Premise: A modern day Indian reservation finds itself in trouble when two rival leaders go toe-to-toe regarding the reservation’s casino.

About: Doug Jung has been scribbling his way up the screenwriting ladder lately, penning the latest Star Trek screenplay, Star Trek Beyond, as well as rewriting the top secret JJ Abrams project, The God Particle, which Jung has re-conceived to make it part of the Cloverfield universe. “Scalped” has been a buzzy project due to it being based on a hip comic book that will star an all Native American cast. No whitewashing here. Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that it will appear on WGN America.

Writer: Doug Jung (based on the graphic novel by Jason Aaron)

Details: 64 pages

I read the other day that Mark Wahlberg was creating a comic book called “Alien Bounty Hunter” for the specific purpose of adapting it into a screenplay so he could build a franchise out of it.

Most writers seem baffled by this new trend – that people aren’t creating comic books because they want them to do well as comic books anymore. But so they can quickly turn them around into movie projects.

I used to get pissed off about this as well. It not only seemed like a cheat. But it spotlighted one of the biggest frustrations writers have about the industry – its fear of buying spec scripts straight up.

However, over time, I’ve warmed to the idea. I’ll occasionally read a big-budget script and struggle to understand what it would look like on the big screen. The great thing about comic books are that they give potential buyers a better understanding of what the project will look like. And when you’re putting 100 million dollars into something, don’t you want to know as much as possible about how it’s going to turn out? I know if it was my money, I would.

So all it really is is a hack. It’s the writers way of saying, “Okay, you don’t take chances on the written word? I’m going to use this workaround then.”

Which brings us to Scalped. Scalped is an example of the way that they used to do things. Nobody created this comic in the hopes of turning it into a TV show or a movie. They just wanted to write a badass comic book! And, if you talk to any comic book geek, they’ll tell you they’ve achieved just that. Scalped is supposed to be awesome. Let’s see if that’s the case in TV form.

Chief Lincoln Red Crow is the biggest name on the Lakota Indian Reservation. He owns and runs the Crazy Horse Casino, which is responsible for most of the money that runs through the community.

But you don’t build casinos on Indian reservations without fucking a few people over. And now Red Crow is paying a price for that. His biggest rival, Henry One Star, comes to him claiming he’s had a “vision,” and that to avoid a war, Red Crow needs to close down the casino pronto.

Visions carry weight in Indian reservations, but Red Crow isn’t so sure One Star’s telling the truth. There has to be something motivating him. So Red Crow sends his men out to find out what’s up.

Meanwhile, Red Crow’s investors, the Hmong from China, are pissed off. The whole reason they invested in this place was because Red Crow ran this town. If Red Crow can’t solve minor problems like this one, they’re going to fly in and solve it themselves.

The truth is, Red Crow used to be a bad dude. He wasn’t afraid to shed blood to get what he wanted. But, recently, he’s made a promise to himself to no longer sacrifice his own people, his own culture, to get ahead. When the Hmong suggest killing One Star, Red Crow is vehemently against it. He’s convinced this can be dealt with diplomatically.

Of course, it’s never that easy. And as One Star ups the pressure, as the Hmong up the threats, and as old flames and estranged daughters come back to weigh in on the impending chaos, Red Crow will need to decide if his violent ways are truly behind him.

When you read any script (pilot or feature), you go into this mode of trying to figure out what it is. Is this a kidnapping movie (Taken)? Is this a garden variety procedural (Law and Order)? Is it a soapy character-driven drama (Parenthood)?

While you’re doing this, one of three scenarios occurs. One, it becomes a familiar thing, like the shows I listed above. Two, it never commits to a show-type and ends up becoming this incomprehensible mess. This is basically most of the amateur pilots I read. Or three, which is the direction every writer should be aiming for – it becomes something in between these two worlds, something that feels both familiar yet unpredictable. I’m talking about shows like Lost, like Taboo, like Better Call Saul.

That’s where I see Scalped.

And the first lesson I learned from this script is that when you start with an unfamiliar world – like an Indian reservation – you increase the chances of creating a show that’s unpredictable, because, obviously, it’s hard to predict that which you’ve never seen before.

But make no mistake. Scalped doesn’t rewrite the screenwriting rulebook. Nor should it. Yesterday, we were talking about conflict. And I’ll talk about it again, even if you’re getting sick of it.

You see, in television, conflict is paramount. It’s more important than in features because, unlike features, you don’t have an entertaining plot barreling forward at a hundred miles an hour. You can’t. There are too many episodes, too much time to fill.

The only thing you have left to entertain with, then, is conflict. What’s at the heart of Scalped’s pilot? Two rivals who are gunning for each other. Conflict with a capital “C.”

Even better, Scalped has placed a THING at the center of its plot that creates conflict in every direction it turns – the casino. You could take all of these people in this town, send them away, bring in a whole new set of people, and you’d still have tons of conflict because of this casino. That’s good writing there. Inject shit into your script that creates conflict for you.

The only missteps Scalped makes is in its storytelling. And this is why it’s so hard to write pilots. You have to set up an entire season of storylines, so that means introducing us to people who aren’t going to be interesting right away.

For example, there’s a character, Gina, who works for the government and she’s trying to get historical status for some of the Lakota land. I know this will become relevant in later episodes. But right now, it’s boring as hell, especially when you have the rivalry of Red Crow and One Star in your back pocket. It’s like when I got a Transformer for Christmas but my parents forced me to play with the slinky Uncle Ned bought me. “But daaaaad! Ironside’s right over therrrre!” (cue Carson crying)

If you ask me, I think you should rewrite a pilot until everything’s entertaining. No scene should feel like a boring setup for a storyline to be explored in a future episode. However, I understand that’s easier said than done. Still, in this ultra-competitive TV landscape, you should try.

Bottom line: Scalped is unique and definitely worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Use your pilot to inject as much conflict into as many things as possible. Remember, conflict is, by definition, unresolved. And since people want to stick around until something gets resolved, it’s in your best interest to create as much conflict as possible. TV is like this sick game. You keep saying to the audience, “This is going to get resolved. You’ll see if you come back next week.” And then next week you say, “I know we didn’t resolve this. But we will soon. Come back next week.” That’s what you’re doing with conflict. You’re creating issues and problems between characters and within the plot itself that remain unresolved for as long as you can get away with it. It’s dirty, but it works.

Congrats to Scott Serrandell who won this past weekend’s dialogue mini-contest. Some really funny dialogue, exactly what I was I was looking for. I’ll be looking forward to see what he does in the official Scriptshadow Short Script Contest.

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from The Black List) A multigenerational love story that weaves together a number of characters whose lives intersect over the course of decades from the streets of New York to the Spanish countryside and back.

About: Dan Fogelman broke onto the scene with the original Ryan Gosling and Emma Stone pairing, “Crazy, Stupid, Love.” His next project, the oldies-Hangover film, Last Vegas (which he made clear to me was written BEFORE The Hangover), was a sneaky hit. Mixed in there were The Guilt Trip and Danny Collins, neither of which did well. Nowadays, Fogelman has moved over to television, with his viral NBC show, This is Us. “Life Itself,” a highly ranked 2016 Black List script, is his return to features and will star Oscar Isaac and Olivia Wilde. Fogelman will direct.

Writer: Dan Fogelman

Details: 116 pages

Dan Fogelman is one of the biggest screenwriting success stories of the past decade. He came out of nowhere five years ago to sell three huge specs at a time when everyone thought the giant spec sale was dead. And he was doing it with the kinds of movies Hollywood doesn’t make anymore, mid-budget light-as-a-feather dramadies with heart.

Things looked bad when one of his biggest sales, Danny Collins, however, failed badly at the box office. It was looking like Fogelman was in trouble. So he just hopped over to the TV side where he now has one of the most buzzed about shows on television (This Is Us). When you think about it, Fogelman’s character-first stories were always better for television anyway. So we probably should’ve seen it coming.

But now Fogelman’s back with a feature. Let’s see how he did.

I have to admit, the last thing I expected when I opened a Dan Fogelman script was Samuel Jackson screaming at me. Yes, Samuel Jackson is our narrator. At least for now. There’s a lot of “at least for now” in Life Itself. To give you a taste of that, we meet Julianne Moore a few pages later. And Julianne Moore gets slammed into by a bus, her bones and guts sprayed everywhere.

Yes, Life Itself is Dan Fogelman unhinged.

Confused yet? I was. Eventually, after things settle down, we meet Will Dempsey, a sometimes-writer who’s devastated by his pregnant wife, Abby, leaving him. Will was so destroyed, in fact, that he spent six months in a nut house. Now he spends most of his days talking to his therapist, who looks a lot like Julianne Moore.

We jump back in time to see how these two met. You’ve never seen two people more perfect for each other and more in love than these two. Which begs the question – how could Abby possibly leave Will?

To answer that question, we’ll need to get into spoilers, as Life Itself is one giant spoiler-fest. Which makes sense since life itself is a spoiler fest. So don’t read on if you don’t want to know what happens. I’ll be semi-vague in order to protect the script’s twists. But what we learn is that Abby and Will didn’t divorce. A far worse tragedy occurred. And that is why Will has gone off the rails.

Oh, but if you think that’s all you’re getting here, let me remind you that Life Itself is DAN FOGELMAN UNHINGED. After getting over the shock of the earlier tragedy, Fogelman hits us with a DOUBLE TRAGEDY that was so shocking, I spent the next ten pages reading the script through tears. No, I’m not kidding.

Without getting into too much detail, we cut to years later where we follow Will and Abby’s daughter, Dylan (named after Abby’s favorite musician, Bob Dylan), growing up, and explore how the tragedies of her earlier life have turned her into the rebellious and dangerous beauty she is today.

In the meantime, we follow a poor Spanish family who is peripherally attached to Abby and Will. And, at a certain point, we realize that that Spanish families’ story is going to loop back around and re-intersect with that of our original characters. But while we’re praying it intersects the way we hope it will, there are no promises when it comes to Fogelman’s most twisty and turny narrative yet.

I apologize that summary was so vague but there are too many major twists and turns and I don’t want to ruin them ahead of the film. That makes this script difficult to analyze but I’ll do my best.

I want to start with bravery. As a writer, one of your jobs is to evolve. Each script you write, you want to push yourself into new, even uncomfortable, territory. If all you’re doing is rehashing the same old characters and storylines that you always do, you’re never going to write anything great.

I did not recognize this Dan Fogelman at all. I remembered in his previous scripts that he always played things safe and predictably. He did safe and predictable well. But you always knew what you were getting from Fogelman, and that kept his scripts from ever elevating into awesomeness.

Life Itself is a whole other beast. At first, Sam Jackson is breaking the fourth wall, screaming at both us and our hero. Then Julianne Moore gets violently slaughtered by a bus. Then we’re hit with two major fucking traumatic twists within a ten page period. Then, for the second half of the script, we’re meeting this whole other family in Spain…

It’s like, “What the hell??”

Truth be told, this story is better suited for a novel or a television show. Whenever you have multiple characters and you really want to delve into those characters (I mean, beyond the basic likable trait and character flaw), you need time. And you can only get that with the 60,000+ words a novel affords you or the 7+ seasons a TV show does.

When you try to do the same thing with a feature, you always run up against the problem of plot. Features need the plot to keep moving. And that always conflicts with character development. Yes, you can do both. And the best writers do. But only to an extent. I don’t care how talented you are. If you need your characters to destroy the Death Star by the end of the movie, you need to keep your plot moving along. And that takes away those slower character-driven scenes that are such a staple in TV shows.

And yet, Fogelman gets as close to pulling it off as one can. I’m not sure how he does it but I want to say the twists are a big part. He knows that because there’s no plot, if he hits you with 40 scenes in a row of characters saying I love you and I hate you, we’ll be bored to death. So he slams you with these huge shockers that we never saw coming and it’s like this jolt of espresso that powers us through another 15 pages of character development until the next twist arrives.

I do think this approach finally bit him in the ass, though. Because the first act was so strong and so unexpected, the second quieter half, with the Spanish family, couldn’t quite live up to it. And while there will always be parts of a screenplay that play better than others, you should try to make it so that each quarter of your script is better than the previous quarter. That’s because you want your final quarter to bring the house down. And in Life Itself, it’s the first and second quarters that bring the house down.

Still, this is quite an achievement. It’s unlike anything you’ll read all year. It’s complex yet a surprisingly quick read (one of Fogelman’s specialities). I would go so far as to say this is his best script. Could it have been better had he hit a home run in the 3rd Act? Sure. But I’d still recommend this to anyone wanting to learn how to write vibrant memorable characters.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As much as I hate flashbacks, there’s no question that they help the reader care about a character more. For example, if I introduced you to John, the hockey player with an attitude, all you see is a hockey player with an attitude. But if, at some point, I flash back to when John was a child and showed that he witnessed his father beat his mother to death, that character is fleshed out ten-fold. He carries so much more weight. That’s what Fogelman does here on multiple occasions and it really helps his characters shine.

The author of the best selling book and mega-smash box office hit, The Martian, comes to bat with his first TV pilot!

Genre: TV Pilot – 1 hour drama

Premise: “Mission Control” follows the NASA mission control unit as they attempt to push a new space station into orbit, which will eventually fly to Mars.

About: Andy Weir, of “The Martian” fame, is coming to CBS with a TV show. Oh, and who’s producing it? Some guy named Simon Kinberg, who’s only in charge of some of the biggest franchises in Hollywood (you may have heard of them – Star Wars, X-Men).

Writer: Andy Weir

Details: 62 pages

Uh, the writer of The Martian writes a TV series about the next generation of NASA.

SIGN ME UP PLEASE!

Andy Weir is in that unique position every writer would amputate their left foot to be in (since feet aren’t required for writing). He’s the author of a hit movie, which means every producer in town wants his next project. If he nails that next project, he becomes a superstar.

But holy shit is TV tough. I don’t know if “competitive” is the right word to use, since there are 400 slots available. But the audience will tell you if they don’t like your show. As soon as those eyeballs disappear, you’re done. Hell, Matt Effing Damon and Ben Freaking Affleck just had their sci-fi show canceled the other day. If it can happen to Mark Watney, it can happen to anyone.

Let’s hope it doesn’t happen to Mr. Weir.

Mission Control follows two factions of people, the folks down in NASA’S mission control unit, and the people up on a next-generation space station called Durga. Julie Towne, a whip-smart leader who burns the candle at both ends, is preparing Durga to move from low-orbit to high-orbit, where it will eventually fly to Mars.

Meanwhile, NASA’S having image problems. Their gorgeous African-American public affairs officer, Rayna, is trying to clean up a nude pics scandal from one of their astronauts, the similarly stunning Deke, who happens to be a heiress to billions. Deke isn’t too bummed out about the fallout since all the feedback from her pictures has been positive.

Back on Durga, they’re awaiting a group of Russian cosmonauts who, I believe, will be helping them fly to Mars. But just before the Russians get there, the power goes out. They get the power back up again, but Julie’s convinced that this could be part of a bigger issue that will rear its ugly head somewhere down the line.

While everything appears to get resolved (for the most part) by the end of the episode, we cut to 14 months in the future to see a giant explosion above earth. Might it be Durga? Might it be the Russians’ shuttle? And what does it mean? Only way to find out is to hand over control… to Mission Control.

A pet peeve of mine has always been pilot title pages that give us both the title of the show, and the title of the show’s first episode. It’s like, dude, slow your roll with all the titles. All I need is one.

But after reading Mission Control, which doesn’t have an episode title (it just says “Pilot”), I understand why an episode title is helpful. Yes, you are writing the first episode of a show that will last multiple seasons. But you also have to tell a singular story within this episode – “a story within the story” if you will. By forcing yourself to come up with a title for this individual show, you’re forcing yourself to think of it as an individual story.

That’s Mission Control’s biggest weakness. The pilot doesn’t really have a story. People are introduced. There’s lots of running around. We’re jumping between the mission control room, the space station, and everywhere in between. But I couldn’t figure out what the purpose of any of it was.

My best guess is that it’s about moving the Durga Space Station from low orbit to high orbit. Which, in plot terms, isn’t exactly, “I just got stranded alone on Mars.” So Weir is working from a place of weakness from the get-go, trying to make something feel bigger than it is.

Any screenwriter with a few scripts under his belt knows this feeling. Instead of admitting that there’s something wrong with the concept, we double-down on it, pumping up every muscle we can to give it strength. When deep down we know… there’s a structural weakness that can blow the whole thing up with single well-placed shot into the exhaust port.

Another issue is that Weir’s strength is in science and research. Whenever any of his characters are talking about science, or Weir’s explaining what happens to a space station that’s lost power, he kills it. But once Weir moves from science to people, there’s a clear loss of confidence that accompanies it.

Let’s be frank. Character was never Weir’s strength. Even Mark Watney, the title character in The Martian, wasn’t some great complex character. He was just a sympathetic guy with a dry sense of humor who was stuck on Mars.

But TV is character. If you aren’t good at character creation – at flaws, at inner conflict, at irony, at uniqueness, at inter-relationship conflict, you’re not going to write anything with legs.

And you can see Weir struggling with that throughout the pilot. The biggest plotline of the episode is Deke’s nude photo leak, which feels like it was ripped out of a Grey’s Anatomy Season 1 episode. Indeed, Weir feels like a guy who doesn’t like Shonda Rhimes being forced to write like Shonda Rhimes. Heck, there’s even a character named Izzy (arguably, Rhimes’s most popular character).

I don’t know what’s going on with that. It might be that Weir is new to the TV scene and watched a ton of popular television to figure out how to write a pilot and came up with this Shonda Rhimes NASA Frankenstein take. Or, maybe this is CBS telling him to make it “more like Shonda Rhimes,” more mainstream.

All I know is that, right now, this has the same problem as Cameron Crowe’s Aloha did. It’s trying to marry science tech with sexy people and those worlds don’t coexist organically. So the final product feels awkward.

Weir needs to take a tip from, well, himself. The Martian was a plot that shouldn’t have worked as a movie. It has an enormous time line, way too much science, and endless plotting. But the producers embraced what the movie was and told it as is. And it worked!

Mission Control shouldn’t be about Kim Kardashian-esque nude photo scandals. It should be about geeky dudes doing really amazing shit. Stick with what got you here, man. Embrace the nerdocity. Unless Weir makes that transition, this show is going to be stuck in outer space.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Have a beginning, middle, and end to your pilot, just like you would a feature. The only difference is that not everything will be wrapped up at the end of a pilot. You’ll still leave some major questions unanswered. But use the Scriptshadow Formula (Goals, Stakes, Urgency) to create a clear story narrative and follow that to the end. In the pilot for last year’s biggest TV spec sale, Designated Survivor, the story was that half of the government was wiped out in a terrorist attack and the newly instated president needed to find out what happened. Boom, there’s your GSU. On the contrary, if all you’re doing is setting up characters while vague plotlines swim aimlessly in the background, you’re not going to have much of an audience by the end of your pilot.