Search Results for: F word

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise (from writer): In a future where robots run grisly human-fighting rings for sport, any human who survives 72 matches is given 72 minutes to win their freedom–or die.

Why You Should Read (from writer): I moved to Los Angeles to specifically pursue a career in waiting tables. I was originally gonna write a biopic about Nikola Tesla’s chef, but figured this would be more interesting. This script has such a big fat concept, that when it took a selfie, Instagram crashed. Do not read it if you hate: space, hyper loops, nihilism, invisible architecture, and futuristic theories. FULL DISCLOSURE: I’m an alien that’s trying to blend in with everyone.

Writer: Robotic Super Cluster

Details: 85 pages

I suppose Game of 72 was the perfect script for today. As I struggle to decide on my last few slots for the Scriptshadow 250, my mind is on the verge of madness. And let me tell you, there isn’t a better script to read when you’re on the cusp of insanity than this one. I want you to imagine Steven Spielberg making A.I., but with Rob Zombie’s brain downloaded into his cerebral cortex. The word “trippy” doesn’t even begin to describe this bizarro eye-assault.

But before I get to that, I want to know which movie I should see and review for Monday. This is the best movie weekend of the year so far, with Sicario (great script), The Martian (great writer success story) and The Walk (amazing special effects) all coming out at the same time! I’m considering doing my first triple-feature in ten years, but I don’t think I’ll have the time. So which one do you want me to review? There’s no wrong answer!

Okay, on to Game of 72, which was my favorite logline of the bunch so I’m glad it won. Well, I should say I WAS glad that it won. Now? I’m not so sure.

The year is 2820. Earth is run by robots, aliens, and genetically modified monsters. The only thing these beings seem to care about is entertainment – specifically human-on-human fighting. They take the humans, chain them up like dogs, torture them, strip them of their names (replacing them with numbers), and force them to fight each other to the death.

Sounds fun, right?

The only way for humans to escape this misery is to win 72 fights (nearly impossible), after which they’re entered into something called “The Game.” In “The Game,” you have 72 minutes to catch a wandering orb. If you succeed, you gain your freedom, are upgraded into a human-robot hybrid, and get the choice to live forever.

So the stakes are high.

Our hero, 28 year old Finn, is one of the few fighters who’s managed to accumulate 72 wins. He joins two others who have managed this impossible feat – Nala and #9560 – and before the trio even knows what’s going on, they’re thrown onto an interplanetary train that shoots them off to Mars.

When they get to Mars, none of the monsters or aliens have ever heard of The Game. They don’t even know who these humans are. In fact, there’s no one to tell them how this game works. Complicating matters is that there’s a disembodied voice living inside of Finn who keeps telling him to do the opposite of what everyone tells him to do.

No more than five pages after we arrive on Mars, our players are told they’re going back to Earth, so they jump on another flight, and arrive into some kind of mind disco. Yes, a “mind disco.” As it’s explained to us, the music isn’t actually being played. It’s “transmitted through everyone’s bodies and souls, emanating from within.” Huh?

I could go on here, but I think you get the gist: THIS SCRIPT IS FUCKING NUTS.

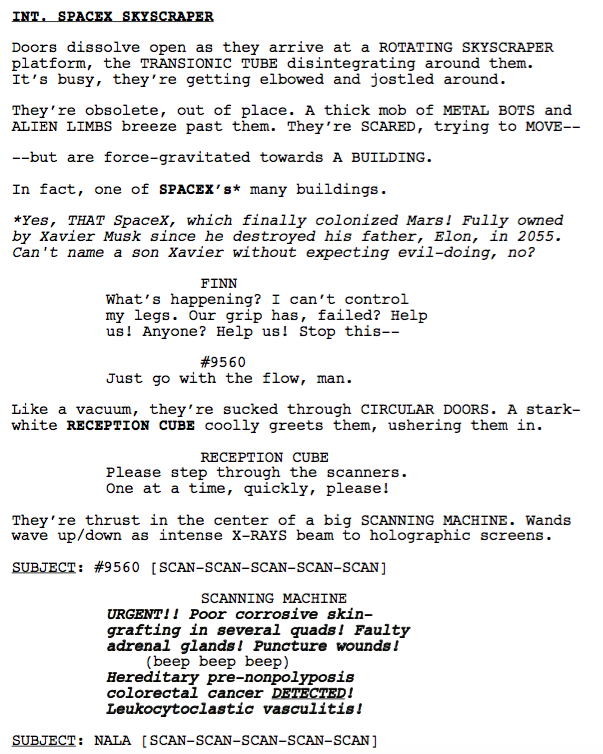

Look, I’m all for imagination. Just yesterday I was complaining about writers who DIDN’T use imagination when writing their queries. But there’s adding jam to your sandwich and there’s dumping the entire jar on it. Game of 72 throws you into an information ocean, never letting you above water to catch your breath. Here’s a typical page from the script:

Let’s see what we’ve got here:

1) Italics-based writing.

2) Bolded writing.

3) Underlined writing.

4) TONS of information.

5) TONS of imagery.

6) Manic writing style.

7) Characters with number names.

The whole script reads like this. Here’s another line, picked at random: “He FALLS, an accordion of 100-copies of him are frozen mid- AIR. Thousands of MAGNOID thoughts enter his head. DEAFENING. The sensation of sinking into LAUGHING GAS, nitrous oxide.”

Huh?

I’m not even sure what to say. I mean, our writer is clearly talented. He had one of the best “Why You Should Reads” of the year. It showed that he’s clever, he’s imaginative, he can write. But it feels like for this script, he ingested an entire Starbucks store and wrote everything freehand, gripping the pencil like a knife, and stabbing 20,000 words onto the page without ever going back to see if he’d murdered anyone. Particularly the English language.

This is a cut and dry case of information overload. Too much style, too much imagination, too much action, too much information. As screenwriters, we do want our scenes packed with action and plot. But there’s a difference between drinking a beer and buying the brewery.

Truth be told there were a couple of red flags before my exhaustion kicked in. People use bitcoin in the year 2820? Space-X (created by Elon Musk) is the main form of transportation? I might buy into this if the year were 2075. The year, however is TWENTY-EIGHT HUNDRED! There wouldn’t be any recognizable brands still around, especially if the world had been taken over by robots and aliens.

The official moment I gave up on the story was when we went to Mars, and after five pages, came right back to Earth. To me, that indecision embodied the script’s biggest issue – its lack of focus. Our writer couldn’t find something interesting to do on an ENTIRELY SEPARATE PLANET, to the point where he had to bring our characters right back to the place they left just minutes ago.

And if you took the time to look deeper, it didn’t seem like anything had been thought out. Why didn’t anyone on Mars know about The Game? And if nobody knows about The Game, then aren’t you telling the reader that it’s not a big deal? And if it’s not a big deal, why should we care if these characters succeed or not?

In the flawed but fun Arnold Swarzenneger movie, The Running Man, the whole world watched that show. The writers made sure you knew everyone on the planet was obsessed with it. So the objective seemed important. With these characters, they’re not even sure if they want the prize (to live forever). Protagonists who aren’t even excited about achieving their goal? That’s a recipe for screenwriting disaster.

I like this writer here. I just think he tried to be too cute and stuff too much into every page. Dial the imagery back. Dial the world-building back. Get rid of the unnecessary details (the 9th version of the monster subset).

I say this over and over and over again, and nobody listens. The best screenplays are simple easy-to-understand stories with complex characters. Once you switch that emphasis around (to a complex story with simple characters), I won’t say you’ve hung yourself, but you’ve definitely tightened the noose.

This script was such an assault on my senses that I almost gave it a “What the hell did I just read?” Seriously, it got to the point where it hurt my head to keep reading. You’re a talented writer and better than this. Let’s nail the next one.

Script link: Game of 72

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Information overload is a script-killer. Nobody wants to be inundated with description-porn on every single page. Dial it back. If it’s not easy to ingest what’s on the page, we’re going to give up on you fairly quickly.

As we near Saturday, when I’ll contact all 250 writers who made it to the next round of my contest, I find myself emotionally exhausted. I’ve read so many stories from writers who have given up everything for this craft. Some have moved from other countries. Some have health problems so severe, they can’t leave their beds. Some are weeks from being kicked out of their apartments. A few are even homeless.

I wish I could make every one of those writers’ dreams come true. But the reality is, I’m not letting screenplays into this contest out of pity. If you didn’t bring your S-game (Script Game), your script didn’t get chosen. And as harsh as that sounds, it’s the way the industry works. If you can’t tell a good story – even in e-mail form – you’re not ready yet.

So today is about highlighting the mistakes I saw in your queries in the hopes that you never make those mistakes again. If there’s a theme to my observations, it’s this: Be professional. If there’s even a hint of sloppiness or laziness in your query, no one’s going to take you seriously. Keeping that in mind, let’s look at the ten biggest mistakes queryers made.

1) Generalities kill loglines – There were a lot of loglines where the writer didn’t give me any actual information. They wrote in vague generalities that didn’t convey what the script was about. Something like, “A mother who questions her life must combat a powerful force that threatens her very existence.” Honestly, it seemed like some of you were actively trying to say nothing. The whole point of a logline is to show what’s UNIQUE about your idea. To achieve that, you must be specific. “When a mother’s developmentally challenged son conjures up a haunting monster known as “The Babadook” from one of his books, she must battle her own sanity in order to defeat it.” That’s what I mean by specific.

2) Word-vomiting kills queries – Beware the writer who takes twenty words to say what they could’ve said in five. These writers add qualifiers and adverbs and adjectives and empty phrases to every sentence they write, making the simplest points exhausting to slog through. For example, instead of writing: “My movie is about a boxer who gets a shot at the heavyweight championship of the world,” they write: “I have a story about a boxer, the kind of man who’s kind, yet forceful when the moment requires it, embracing the challenge of a world that seems to be, but never overtly tries to be, his worst nightmare, and the way that man, my main character, struggles to achieve and eventually is able to secure, a chance to fight for the heavyweight championship of the world, in Philadelphia, the city of brotherly love.” STRIP. YOUR. QUERIES. OF. UNCESSARY. WORDS. PLEASE. GOD.

3) Lack of conflict in a logline is a deal-breaker – You need to convey what the main conflict in your story is. Conflict is story! It’s the problem your main character must overcome to get to the finish line. I read a lot of loglines like this: “A young man experiences a spiritual awakening when he switches from being a Christian to a Muslim.” AND???? What is the conflict that tries to impede upon this switch? Lack of conflict in a logline means the writer doesn’t know what conflict is. If that’s the case, their screenplay is guaranteed to be boring. I mean 100% of the time guaranteed. Guys, if you don’t know what conflict is, go spend the weekend googling it.

4) The words/acronyms “CIA,” “agent,” and “FBI” combined with “terrorist threat” do not, on their own, make a movie – I must’ve read 50 loglines that were some variation of, “A CIA agent goes undercover to tackle a terrorist threat in London.” Secret agents and terrorist threats are some of the most potent plot elements in the movie universe. But they’re worthless on their own. They need a unique element to team up with.

5) Trending subject matter will always have an advantage in the query department – The trend of the moment is biopics. They’re the only thing that’s selling. So I admit that when I came across a biopic, as long as the query was competently written, it got in. Remember that everybody involved in the movie-making chain is trying to sell the project to the next guy up the ladder. I know Grey Matter will have to sell the winning script to the studio at some point. And the studio is more likely to buy a genre that’s doing well at the moment.

6) Focused loglines were always the best entires – One of the easiest ways to identify strong contenders was a focused logline. Unfortunately, the far more common logline was one that started in one place and ended someplace completely different. So I’d get something like this: “A down-on-his-luck mobster trying to open his own casino joins a cooking class and falls in love with his teacher.” Whaaaattttt??? How did we go from casinos to cooking class??? I saw this a LOT and the scary thing is, the writers who made this mistake are probably reading this right now and have no idea they’re guilty of it. That’s because everything connects logically in your own head. It’s only through objectivity that we see disjointedness. Take a step back and make sure you have a FOCUSED movie idea whose beginning, middle, and end, all tie together.

7) The overly mechanical query is digital Ambien – I read a lot of queries where writers were logical and succinct and measured in their pitch… and that fucking bored me to pieces. What these writers were saying was fine. It was HOW they were saying it that was the problem. There was no life to their words, no fun, no spontaneity. I’d read stuff like: “My goal was to eliminate the passive protagonist that’s been an Achilles heel to this sub-genre and replace him with a character that embodies the ideals of the thematic construct of revenge. In doing so, I’ve achieved an energy that was missing in my earlier drafts, but which I could never pinpoint. The resulting script is one that utilizes four out of five of the story engines that drive the classic “man vs. nature” tale…” AHHHHH! KILL ME NOW!!! Writing is supposed to be FUN TO READ. Even when you’re making a serious point, there should be a relaxed easy-to-digest demeanor to your writing. This style of query 100% OF THE TIME means the script will have no voice. So these queries were the easiest to reject.

8) Beware the logline that is at war with itself – I read a lot of loglines that felt like civil wars, with words jockeying for position as opposed to working together harmoniously. These writers had the “stuff it in there” mentality that should be reserved for the condiment section at a hot dog stand, not an e-mail query. Here’s an example: “A cowardly gunfighter is at odds with his idealism and the secrets he’s kept when a rival gunsmith rides into town, looking to settle a score that will help forge the frontier line between New Mexico and California.” A logline isn’t a contest to see how many words you can include. It’s a vessel to get your idea across as simply as possible. It should flow. If it doesn’t flow, rewrite it.

9) Don’t use weird adjectives to describe your main character – Every tenth logline I’d read, I’d get something like this: “A pestered train conductor plans a heist…” “Pestered???” The character adjective should give us both the defining quality of your hero, as well as CONNECT your hero to the plot of the movie. So let’s say your script is about a train conductor who decides to rob his own train. The adjective might be: “An exemplary conductor is forced by his wife to rob his own train after losing his family’s life savings.” I don’t love this logline but at least the adjective connects with the plot. This is a conductor who’s built his career on trust. He’s the last one you’d think would rob his own train.

10) Avoid the cliché opening-page overly-poetic description – Whenever I was on the fence about a query, I’d pop open the script and read the first few lines. If the overly poetic description opener made an appearance, it was bye-bye scripty. What is the “overly poetic description opener?” It’s when a writer who’s clearly uncomfortable with poetic descriptions starts their script with an overly clunky poetic description: “The sun-dappered late-afternoon light plays tic-tac-toe with the suburban rooftops.” No. Just no. Look, if describing an image in a poetic manner isn’t your forte, start with something else – an action, a mystery, your main character speaking. But if you dapper any suburban rooftops, goddammit I’m shutting you down, son.

If I could give writers one piece of advice when it comes to querying, it’d be the same advice I’d give them in regards to screenwriting: FOCUS. Get to the point. Convey your idea clearly. And being entertaining doesn’t hurt. It’s important to remember that you’re trying to convince a person to read something of yours BY READING SOMETHING OF YOURS. So if the short version of your writing isn’t enjoyable, there’s no way they’re going for the long version. Make your query focused and enjoyable to read, and there’s a good chance that reader will give you a shot.

Genre: Thriller/Serial-Killer

Premise: A killer exploits society’s over-reliance on mobile technology to pick off his victims one by one.

About: Today’s writing duo is one of the hottest in Hollywood. They shot onto the scene with their heavily hyped debut spec, “Die in a Gunfight” (straight out of college, no less). Unlike a lot of writers who get a sale and disappear into obscurity, they parlayed that sale into a few writing assignments, eventually landing one of the coveted Marvel projects (Ant-Man). That job has led to a job on Transformers 5. Make fun of Transformers all you want (I do) but landing a writing job on a summer franchise film is a huge freaking deal. Low Tide is a script the writing team sold to 20th Century Fox last year. This is a more recent draft.

Writers: Andrew Barrer & Gabriel Ferrari

Details: 121 pages – 3/21/15 draft

What in the sam hell?? We’ve got a sequel-free, remake-free, biopic-free, not a true story, based-on-absolutely-nothing official spec screenplay here! If I weren’t such a cynic, I’d say that we’re reviewing a piece of original fiction. It’s been so long since I’ve actually done that, I’m not sure I’m qualified to do it anymore.

The way the spec market has gone, the buyers want you to stay in HARDCORE genre lanes. Like “Bed Rest,” which sold to MGM last month. That’s a clear horror genre flick that can be marketed right out of the Final Draft box. I was just reading an article about Robert Zemeckis’s new film, The Walk, and he said that every single production company and studio in town turned the project down. When asked why, he said, simply, “It doesn’t fit into any slot, if you know what I mean.” That’s the way this business works. So for Barrer and Ferrari to go against the grain and give us an offbeat serial killer flick, you gotta give’em knuckles.

But The question that kept popping up while reading Low Tide was, how far off the beaten path can you take a genre? Did these two go too far?

30-something Shae White is not your average detective. Not only did she lose her sister in a murder-suicide when she was just a girl, but she spends her off-time going to sleazy Atlantic City hotels and banging strangers with the explicit rule-set that they tell her they love her, despite her wanting nothing to do with them afterwards. She even keeps the dirty panties from the sex-sessions in a giant drawer in her bedroom. Hash-tag naughty.

Shae is assigned to a strange case where her daughter’s future boyfriend is attacked by a shark and loses his leg. When the police go fishing for the leg, they instead find another leg, that of a recently deceased female.

When the police find the rest of the female, they learn she was murdered, but they decide not to share this detail with the public in fear of wiping out 4th of July tourist traffic on the Jersey Shore.

Shae teams up with another detective, Pete, and the two discover that a man named Robin Goodfellow is texting young women from the fake accounts of their lovers in order to lure them into murderous situations. Goodfellow is sort of a cross between Jigsaw, Scream-Villain, and Hannibal Lecter, a philosophizing recluse who enjoys playing people for chess pieces.

It isn’t long before Goodfellow begins targeting Shae, texting her and calling her with an untraceable fake electronic voice. But Goodfellow may be targeting someone above his pay grade this time. Shae gradually puts the clues together and finds our psycho recluse, leading to a showdown that will leave only one of them able to keep texting those “lol’s.”

There’s a part of me that respects what Barrer and Ferrari have done here. One of the hardest things about screenwriting is walking that fine line between embracing traditional screenwriting structure, and adding just enough messiness to keep your script unique.

This is often what leads to that coveted “voice” we hear so much about but rarely understand. The way in which you break those well-worn rules is what makes your voice different, is what makes your work feel like you. But here’s where the “fine line” thing comes in. Those detours only look good if they work. And I’m not sure they worked in Low Tide.

Right from the start, I had a hard time finding my footing. We start with a cool scene where a girl gets a spooky text from someone while with her boyfriend. The text says only, “He knows.” It turns out our girl has been unfaithful, and now she’s in an isolated area with a guy who, if the texter is to be believed, plans on harming her. So she runs, and it doesn’t end well.

We then go to a woman throwing her dirty panties into a post-sex dirty panty pantry. We then jump to a girl who may or may not be her daughter (it isn’t made clear) who watches as the boy she has a crush on gets his leg bitten off by a shark. We then watch the police fish out the boy’s leg and bring it to the hospital to be reattached, only to realize it’s a different leg. We then find the source of this different leg – the now-murdered girl from the opening.

I suppose it sort of makes sense but it was all so disjointed that 30 pages in, I still didn’t know where the script was going. Eventually our killer, Robin Goodfellow, is introduced, and he provides some connective tissue to all this madness, but Low Tide spent the majority of its tide just trying to make sense.

I mean I’m still not clear on how Goodfellow kills his victims. He doesn’t do it himself, since he stays in his little room the whole time. I guess this means he recruits others to do it. But that’s pretty far-fetched, the idea that you can recruit random people willing to partake in your weird text and fake-electronic-voice phone murders.

That wasn’t the only sloppy part. One of the ways you can tell a script’s not working is if key characters disappear for long chunks of time. This indicates the writers weren’t thinking things out ahead of time or don’t know what do with the characters. Nancy, Shae’s daughter, gets a couple of key scenes early on (saving our shark-attacked boy), and then disappears for 40 pages at a time.

I know there’s an ongoing war in the screenwriting community between outliners and non-outliners, but this is where outlining really helps. You can see exactly where characters need more time and where they don’t.

The movie inspirations here were also too heavy. The shark attack and subsequent “hidden from the public to keep profits up” storyline was ripped straight out of Jaws. The electronic voice stuff was taken straight out of Scream. And our serial killer manipulating our female lead was too similar to Silence of the Lambs.

Look, it’s hard not to include plot points and characters from our favorite movies. That’s why we became screenwriters in the first place. Because we love movies! But the way you want to approach imitation is the way actors study subjects they’re going to play. They don’t ape their mannerisms or do impressions of those people. They take the ESSENCE of the person and let it inspire their own unique performance.

Take the ESSENCE of what you see in the filmmakers and writers you enjoy and apply that to your script. Avoid applying direct plot points and characters. I particularly see this problem with young screenwriters. For whatever reason, they’re more prone to bring in stuff from the movies they love. Veteran screenwriters actively look to create their own storylines and strive to be different from their predecessors.

The good news is, these two are visual writers. They’re definitely thinking about what’s going to be up on that screen. And that’s important. A woman stalking around in a sex-dungeon wearing a half-destroyed Pinocchio mask while an electronic voice taunts her is major trailer material.

And Shae’s weird sex addiction was compelling as well. The whole insisting on people telling her they loved her, while actively avoiding love, while also keeping this bizarre panty memoir. That had me wondering what this woman was going to do next. If you can write characters that have readers turning pages because they want to know what they’re going to do next? That’s a rare talent.

But in the end, this felt too patch-work for me. And I couldn’t get over the stuff taken from other movies. These guys are definitely talented and have a unique voice. But you can’t be unique if you’re blatantly bringing other movies into your story. I’ll be interested to see what you guys thought. There’s a bit of True Detective in Low Tide’s DNA. And I know you all loved that show (me, not so much!). This cold be one of those “Carson hates, but everyone else loves” scripts??

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t write like a virgin. – There’s an old saying that pops up every once in awhile: “Kiss like a virgin.” It refers to the over-the-top, heavy lip and tongue, intense over-compensating kiss you give when you haven’t had sex yet. There’s an equivalent in screenwriting. “Write like a virgin.” This is when writers use big words, throw in a lot of heavy “look at how smart I am” philosophizing by characters, rounded up with lots of references to historic literary titans (both Twain and Nietschke get some love in Low Tide). This kind of writing, if overdone, makes the writer look insecure. The veteran pros know that it’s all about story. They don’t need to prove their worth in every line. If the sentence, “He walks over and grabs his wallet” is all that’s needed for the moment, despite it being an overly-simplistic presentation of the action, that’s what they’ll use. I wish Barrer and Ferrari would stop trying to prove how much they’ve read or studied or how many big words they can use and just write. They’re talented guys. Why all the fireworks?

Today the “spotlight” is on a new Liam Neeson thriller. But can Carson recover enough from yesterday’s script to enjoy it?

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A commuter gets a phone call informing him that if he doesn’t find a specific man on that train before the last stop, his wife and daughter will die.

About: I remember when this script hit the scene forever ago. Like a lot of scripts in Hollywood, it made some noise and then disappeared into the ether. What’s crazy about this town, though, is that if you don’t give up, if you keep improving and pushing the stuff you believe in, sooner or later, something good comes of it. And that’s exactly what happened here. The Commuter has caught the attention of one Liam Neeson, who’s just turned this into a Go picture. Writers Byron Willinger and Philip de Blasi have patiently waited 7 years, not securing a single credited writing assignment in TV or film in the meantime. And now, finally, their lives are about to change. Don’t you love this business?

Writer: Byron Willinger & Philip de Blasi

Details: 101 pages (3/28/08 draft)

In retrospect, could a script titled “The Commuter” have starred anyone other than Liam Neeson? It’d be like naming a script, “Quick Kill,” and expecting anyone other than Jean Clade Van Damme to be the lead. Neeson seems to be tailor-made for these one-word vague action-esque titles. But is the world getting sick of the “Neeson setup?”

I mean, in Non-Stop, Neeson gets a series of texts telling him he has to act or something terrible will happen. Here, he gets a series of calls telling him he has to act or something terrible will happen. Does that make this an unofficial sequel? Is part 3 that Neeson receives a series of tweets that he must act or something terrible will happen? “Liam, you must visit 100 websites before the end of the hour or death. #hurry.”

Truth be told I needed this script after yesterday’s monstrosity. I still don’t know why people are defending Spotlight like it’s some amazing script. There isn’t a single good moment in the script that isn’t purely due to the true story it’s based on. In other words, every good part is a part the writers had no choice but to include. As for everything else, stuff that needed to be writer-generated (like character exploration and character conflict) there was NOTHING. Ugh. I so needed some empty commutering to move past it. Please be good straight-forward Liam Neeson thriller. Please be good.

Michael Woolrich is a former cop famous for solving one of the city’s most notorious murders. But he’s moved past that life for reasons we’ll find out later. Now he works a calm office job, gets to spend a lot more time with his wife and daughter, and he’s happy. In fact, he’s going out to dinner with his wife tonight.

All he has to do is do what he does every evening. Get on the train and travel back from the city to the suburbs. Seems innocent enough. Well it ISN’T INNOCENT MOTHERF&^%ERS. Cause Liam Neeson is in this movie. And when Liam Neeson takes transportation somewhere, something always happens.

Indeed, Liam – I mean Michael – gets a call informing him that he needs to find someone named “Devlin” on the train before the train gets to its last stop. Apparently, there are two Feds at the last stop, waiting for Devlin to show up, because he witnessed a big murder. Once Michael finds Devlin, our phone-caller (and his mysterious crew, who are also on the train somewhere) can kill him to make sure he doesn’t tell the Feds what he knows.

Being the star detective that Michael is, this should be easy. The problem is that Devlin is an alias. And Devlin doesn’t WANT to be found. So this is going to be a little more challenging than your average investigation.

Throughout the 60 minute train ride, Michael will misidentify several Devlins, make some horrible mistakes, get booted off the train, and almost get his family killed several times. When he finally does figure out who Devlin is, mere minutes before the train reaches its destination, he will have to make the most difficult decision of his life. Should he kill Devlin himself to save his family?

The Commuter is bit like a game of monopoly. When someone mentions you should play, you hem and you haw and try to get out of it, but 45 minutes later, you’re excitedly rolling the dice, hoping you land on Boardwalk so you can take everyone’s money. This little script really does grow on you.

I think that’s because I had no fucking idea who Devlin was. Usually in these simplistic thriller “mysteries,” you know the killer before we’ve gotten out of the first act. But as Michael continues to bounce around well into the second act, you realize you don’t have the slightest clue who Devlin is.

If there’s a takeaway from this script, it’s that. If you’re going to write a simplistic thriller premise, then you better be WAY THE HELL AHEAD OF YOUR READER. Because if the reader gets ahead of you in a script like this, they’re going to be sooooo bored. There simply isn’t enough complexity in a plot like The Commuter’s to withstand a lot of other script issues.

I must admit, though, that I’m tired of the “random person calls and tells the protagonist he must obey” plot device. Starting all the way back with Die Hard 3, moving into Phone Booth, and more recently with, well, a dozen films over the last decade – there’s something lazy about it. It doesn’t take a whole lot of creativity to come up with the setup.

A man is on a Cruise Boat and gets a call that unless he commandeers the ship within the next 45 minutes, everyone on the ship will die.

See, I just did it.

Maybe it’s because the main character becomes a reactive pawn. They’re not pushing the movie forward. They’re following orders. I mean, how much more badass is John McClane in the original Die Hard as opposed to Die Hard 3 where he’s running around like a chicken with his head cut off, doing whatever this loser tells him to do? And that’s because when you’re following orders, you’re a reactive little bitch. It’s not hero-ish.

So again, if you’re going to go with this setup, you better be ready to execute. You better have a mystery that’s truly a mystery, and not just a “passing-the-time” Screenwriting 101 plot outline that any screenwriter could come up with.

Commuter shows off its metal when we finally find out who Devlin is. It forces our main character to make an IMPOSSIBLE choice. And that’s always good writing, when the writers put the main character in a situation where there is no right answer, where even the audience isn’t sure what they would do.

There were other nice touches here as well. In the B-storyline, which is the bad guys kidnapping Michael’s wife and daughter to motivate him, I liked how they didn’t already have the wife and daughter when they first made their threat. They were merely AFTER the wife and daughter.

So early in the script, we see the wife and daughter shopping, and then one of our bad guys watching them, planning how he’s going to kidnap them.

The reason this is such a smart move is because it adds uncertainty to the B-plotline. We’re still hoping that, against all hope, the wife and daughter might be able to escape. When you create uncertainty in a plotline, you get more mileage out of it. If, when the bad guys originally called Michael, they already had the wife and daughter in the basement, well, there isn’t a whole lot of uncertainty or hope in that storyline now is there? Its dramatic potential is at the end of the line. So yeah, I like how they gave us another exciting plotline to jump to.

And the script throws in a few nice surprise twists as well, specifically on the character front. One of my big beefs with Spotlight was that we knew NOTHING about the characters. They didn’t even try to make them real people, despite the fact that they were real people! And yet here, with Michael, a completely fictional person who’s never existed in the real world, we learn a HUGE revelation about his past that makes us rethink his entire character.

Do I think The Commuter is going to challenge Spotlight for an Oscar anytime soon? Of course not. People vote for movies like Spotlight because they’re important movies telling an important story. But if you’re looking to be entertained and thrilled, The Commuter will do the job.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Guys and gals, stop describing your characters with some variation of the description: “She looks worn down and tired, but you can still see her once-prominant beauty underneath.” “Tired/worn-down but still beautiful” is one of the most overused description-types I see. I guess it’s not the worst way to describe someone. Just know that it’s not exactly original.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Horror

Premise (from writer): A strange old man tells scary campfire stories to two young boys. But who is the man, why are the boys in the stories and where are their parents?

Why You Should Read (from writer): Early in the year, you wrote a couple of posts, the gist being – You want to stand out in the current spec market? You need to take risks. So, I sucked up that advice, threw caution to the wind and the result is this very different little horror script. It takes the sort of structural and narrative risks I normally wouldn’t.

Writer: Ashley Sanders

Details: 86 pages

Atmosphere.

Every horror film needs it.

But how much atmosphere is too much?

The most atmospheric horror movie of all time is probably Suspiria. Story is placed on the back burner in favor of terrifying imagery and eerie music. And it works like cheese on tacos. You don’t forget that movie after you’ve seen it.

Which I’m guessing was Ashley’s inspiration here. She says in her WYSR that she wanted to move away from convention. As long as you have a solid understanding of storytelling, I encourage this.

But what I often find happens to a writer going off on one of these “experimental” journeys is that they embrace the “fuck it” attitude a little too excitedly. It’s as if they think NOTHING should make sense, less the script fall back into the dreaded “c” word (convention).

But even when you’re writing something different, you still need to follow some rules. Just like if you wanted to build a house that nobody’s built before, there are still some common things you’ll need to add – like walls.

Small Slices walked that line a little too liberally and while there’s some good stuff here, I’m not sure there are enough walls to keep it from falling down.

The script takes place in a forest at night, with a man known simply as “the storyteller” telling two brothers, Mark (7), and Tom (9), (both played by Michael Shannon), a series of scary stories.

The stories center on a family led by shady businessman David and his trophy wife, Sara, who have two kids named, you guessed it, Mark and Tom.

One day, the couple receives a mysterious grandfather clock in the mail. While their initial inclination is to turn it away, the thing looks so old and interesting that they figure it might be worth some money, so they keep it.

Tick tock. Bad move.

Every night at 4:20 AM, the doors to the clock open and some creepy cardboard puppet-kids come out and do a little creepy dance. This is followed by the sound of scratching, which eventually moves beyond the clock and into the walls of the house, resulting in a lot of spooked out family members trying to figure out what the hell is going on.

Occasionally, we’ll break out of this story to come back to the Storyteller, who will tell little side stories about the characters, some of which turn them into different people doing inexplicable things.

One of my favorites was when Sara walks through the park to see a man standing next to tree with a bunch of whining dogs tied up to it. It turns out the man is digging a hole to bury the dogs in. He asks for Sara’s help, and she obliges.

But as the hole gets deeper, the man disappears, and the park’s residents, furious that this woman has stolen all their dogs and was planning to bury them, proceed to bury Sara alive! Yeah, talk about creepy!

Eventually, our family gets rid of the grandfather clock, but by then, it’s too late. The clock’s scratch-happy inhabitant has moved into the walls. And he’s not leaving until he turns a few family members into clock pie.

Just from this synopsis, you can tell there’s some fertile horror ground to play with.

But the script’s over-dependence on dream sequences made it hard to stay interested in. Dream sequences don’t fit well into movies. You should avoid them like gas station hot dogs. The few that succeed, though, tend to be of the horror variety. That’s because you can throw some creepy shit in a dream sequence and people will be scared.

However, if that’s all you’re doing, after awhile, the audience will pull ahead of you. They figure out your trick and get a general sense of what you’re going to do before you do. Once the audience is ahead of the writer, the movie’s dead. You can’t allow the audience to lead the parade.

For instance, we get a late scene where David is on a subway train and you just know he’s going to see something creepy (in this case, a woman with a weird screaming baby-face). Cause that’s how all these dream sequences have been.

1) Character enters location.

2) Something feels off about location.

3) They see something creepy.

The reason my favorite scene in the script was the Sarah-buried-alive scene was because it went against this formula. It was a different scenario that we weren’t used to.

This is something writers should be concerned about across all genres. Are they repeating themselves? Because if you’re repeating yourself in any aspect of the story, you’re giving the reader the opportunity to get ahead of you.

As I’ve said before, your job as a writer is to constantly monitor what you think the reader is expecting so you can give them something different. Use their expectations against them!

There’s a reason The Shining is more popular than movies like Suspiria and Jacob’s Ladder. All three films are good in their own way. But The Shining puts the most thought into its story. I strongly believe that audiences want to be led somewhere. They want you to take them. And if the rules get too blurry along the way, you lose them. Or at least, you lose a lot of them.

You also want to keep in mind that while this would probably make a really cool looking movie (there’s some creepy-ass imagery, that’s for sure), horror directors are experts in coming up with creepy-ass imagery. They don’t need you to achieve this part of the puzzle. What they don’t have, however, is the ability to come up with a captivating story. That’s where they’re weakest and so that’s your main way to tempt them. Give them a story they can’t say no to.

With that said, there’s something interesting about the writing here. There are some strong moments (the aforementioned buried-alive scene). I loved how Ashley SHOWED instead of TOLD in a lot of places. It’s just that, on the whole, it felt a little half-baked. You finish and get the sense that the fireplace storyline wasn’t thought through at all. You could’ve created some real tension in those scenes and punctuated it with a nice end-of-the-movie twist. Instead, the kids just go back into their tents and call it a night.

But hey, nobody said this screenwriting stuff was easy. Ashley’s got the tools. I’d like to see her use those tools to build a better foundation though.

Script link: Small Slices

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware the dream sequence in any of its forms. And if you are going to use it, use it sparingly. Most readers/audiences will get impatient if too much of the story is told in a formless state. Solid foundation-based storytelling is the way to go. Trust me!