Search Results for: F word

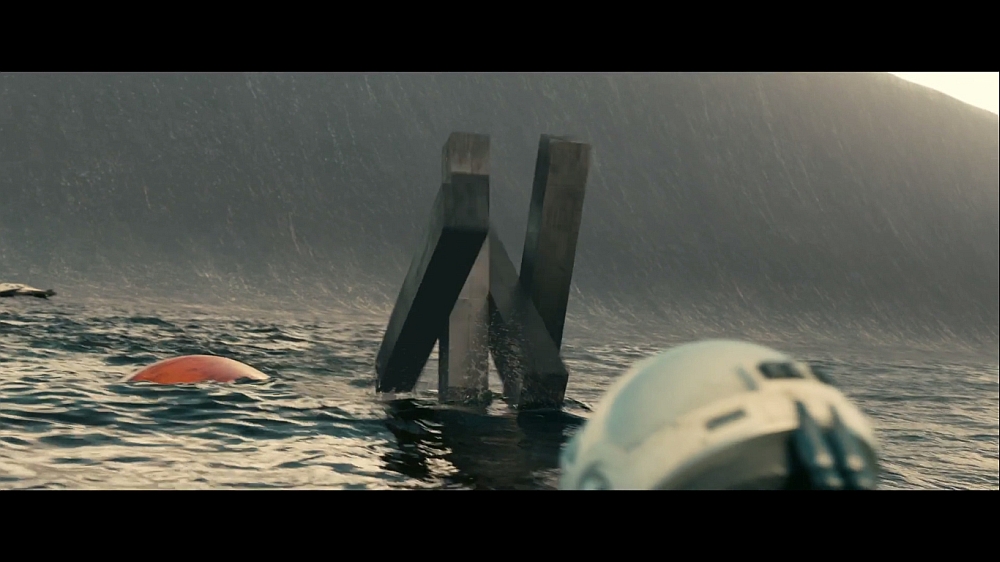

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: A small team of astronauts go out into the universe in search of potential new homes for the inhabitants of earth, who are experiencing a rapidly dying world.

About: Interstellar opened this weekend and did quite well at the box office, finishing in second place (with 50 million) to Big Hero 6 (hey, who’s going to beat an animated Disney movie at the box office?). The project was originally going to be directed by Steven Spielberg many years back (isn’t every movie at some point?). After he left, writer Jonathan Nolan kept working on the script, eventually convincing his brother to direct it.

Writers: Jonathan Nolan and Christopher Nolan

Details: 170 minutes

People seem to be all over the map on this one.

Some critics believe the film is laughable. Yet a lot of commenters (on various sites) have called it a masterpiece.

It seems like you have to either love or hate Interstellar. And as much as I want to fall on one side or the other to give the film/script that definitive stamp of good or bad, the reality is, this is a very mixed bag.

I do want to state the obvious though. Regardless of the quality of the film, Christopher Nolan is doing God’s work. The man is making big-budget original movies when he could be getting paid five times as much doing what everyone else in this town is doing – riding the superhero gravy train. Yeah yeah, he did Batman. But it was clear he didn’t want to make the third one. Which means between this and Inception, the last 7 years or so have been dedicated to infusing the box office with some of the only big-budget original entertainment out there.

Before we get into the juicy details, here’s a breakdown of the plot for those who haven’t seen the film. Coop is a former astronaut in a near-future world that’s running out of food. He somehow stumbles across a hidden NASA base, whose president informs him only hours after he arrives, that they need him to lead a mission to save the world.

They found a wormhole near Saturn that allows them to jump to another galaxy. There are three potentially habitable worlds in this galaxy. Coop is to head a small team that will check out these worlds, and hopefully verify that one is perfect for us to colonize. Coop has to leave his son and daughter for the mission, who we periodically check back in on, all the way into adulthood.

While the first act (which establishes the state of the world) is effective, it’s also really clunky. Early on we get a strange scene where Coop is driving with his daughter (Murph) and spots an “Indian drone” flying around. They chase it through the cornfields (how does a jeep going 30 miles an hour through a cornfield keep up with a drone that’s going 100 miles an hour?).

Apparently, according to Coop, the solar cells on this drone will “power the farm” for years. So they chase it and somehow hack into it with a computer and land it. The scene’s intent is a sweet one – a unique bonding moment between father and daughter – but because the drone causes so many frustrating questions, it impedes upon this intent. It’s an Indian drone? What is it doing in America? Also, if its solar panels can “power the farm for a year,” how come we never see these “solar panels” in action? In fact, I didn’t see any solar panels on the drone at all.

This is followed by one of the most confusing moments in the script. During a dust storm, Murph forgets to close her bedroom window. Dust then flies in and creates a pattern on the floor that Coop believes is a set of coordinates that he must travel to and check out (uh, sure). So he and Murph get in a car, drive all night, until they get to some private land that turns out to be, of all places, NASA, which has been hiding underground for years.

NASA is now run by Cooper’s old boss, Professor Brand, who informs Coop that they’re launching a mission in a week to look for new planets. And, oh yeah, since Cooper is the best astronaut in the world, he wants him to pilot the mission!

Whoa whoa whoa, what???

In old screenwriting circles, this is called: “lazy fucking writing.” So let me get this straight. Cooper finds a space institution he didn’t know still existed through dust coordinates in his daughter’s bedroom, and minutes after he arrives, he’s being asked to join their mission that leaves in a week??? Might that be the single biggest coincidence in the history of the world?

Like many of you, I wondered, if Coop is the best pilot in the world, why didn’t Brand go get him himself? This is “explained” in one of the many cheat lines in the screenplay, with Brand saying something to the effect of, “We didn’t even know you were still alive.” Oh give me a fucking break. You’re about to travel through a wormhole to another galaxy to explore three new planets and you didn’t think to check if the greatest astronaut in the history of the planet was still around?

Anyway.

This is followed by one of Nolan’s biggest weaknesses: clunky exposition. We’re given an extremely elaborate mission breakdown that includes plan As and plan Bs, jumping through wormholes, 12 total worlds, 3 promising worlds, past missions, black holes, singularities, time slippage, one way communication, and, of course, Interstellar’s favorite topic – gravity.

This is where things get really convoluted. Apparently, Professor Brand is working on some sort of gravity displacement technology that will allow him to raise NASA up into space, because the underground NASA structure is also doubling as (get this) a space station. He tells Coop that when he comes back, he’ll have solved this gravity problem, which, I think, means he’ll be able to use gravity to send the whole of earth’s population through the wormhole to one of these new worlds.

Uh, come again?

Anyway, once we get into space, the movie finally starts coming together. Gone are many of the convoluted plot points, and we’re finally able to just… breathe. Or, more appropriately, explore. Actually, that’s not 100% true. There are still some convoluted plot points and exposition, but now Nolan can use our ignorance of space, time, and the universe against us. I don’t know if a Black Hole outer-sphere really makes 1 hour the equivalent of 7 earth years, but it sure sounds cool so I go along with it.

But the exploration of the worlds really was cool. And the worlds allowed the film’s real star to emerge, TARS. If I’m going to take the writers to town for their laziness, I have to give them props for their creativity. TARS was the most original and lovable droid since R2-D2 and C3PO. He was unique and fun and unexpectedly versatile. When he goes to save Brand (Professor Brand’s daughter – played by Anne Hathaway) on that water planet as the tidal wave is approaching and he transforms into some windmill apparatus to speed through the water, it was one of those moments of pure movie magic.

This brings us to one of the most hotly debated segments in the movie (surprise casting spoiler), the Matt Damon sequence. From what I gather, the people who hated the rest of the movie loved this moment. And the people who loved the rest of the movie hated this moment. That’s probably because the Damon sequence was an entirely different genre from the rest of the film – it was a thriller.

I liked it, even if it did feel a bit out of place. The sadness behind that character is what sold it for me. Him being there for so long, all alone. It brings up questions that it sounds like we’ll be dealing with soon – as there’s this “mission to Mars” plan that will entail sending a single person to die on the planet. Along with the other crew member on the previous planet trip having to wait 23 years for Coop and Brand to return (every 1 hour on the water planet equaled 7 years in orbit), there were some really fascinating questions posed here about time and loneliness and its effect on people.

TARS needs his own movie! Preferably a team-up with John Wick’s dog.

TARS needs his own movie! Preferably a team-up with John Wick’s dog.

Up until this point in the film, I’d probably give Interstellar a double worth the watch. Despite is flaws, its pure grandiosity was magnetic. I think it’s sad that we aren’t pioneers anymore. I was more than happy for Christopher Nolan to show me what it would be like to explore again, even if it was a fictional experience.

And then…

And then Christopher and Jonathan Nolan start the bullshitting. Either that or they got lazy or they simply ran out of time. Because everything that happens in the last 30 minutes of this movie is pure hogwash. It feels like a couple of stoned college seniors forgot their term paper was due the next day, and scrambled to write the last 7 pages in a drug-induced stupor.

I mean come on. Cooper goes into the center of a black hole, encounters a “five-dimensional reality within a three-dimensional space,” which amounts to an infinite recreation of his daughter’s bedroom. In order to stop himself from going on this mission in the first place, he sends binary code through the second hand of an identical watch he gave his daughter…

I mean do I even need to go on? This is such “wrote myself into a corner now I’m going to bullshit my way out of it” I don’t even know what to say. With supernatural set-ups and payoffs, there’s something you need to establish that I call the “Immaculate Connection.” This is where you give the reader enough information so that the payoff’s arrival makes sense.

The Force is a good example. The Force is explained to us. We see it in action numerous times. This helps us understand how it works. Therefore, when Luke uses the Force at the end to destroy the Death Star, it makes sense to us.

This was the opposite of that. This was, “throw as much psychobabble bullshit at the wall as possible in the hopes that the viewer gets distracted enough that whatever vaguely connected payoff we throw at them will be sufficient.” I HATE IT when writers try to bullshit an audience. It’s your due diligence as a writer to give the viewer a satisfactory ending that makes sense within the construct of the imaginary world you’ve created.

I love that IGN (very politely I may add) called Jonathan out on his bullshit in an interview question. And Nolan’s answer verifies my suspicions. He made all this shit up on the fly. Here’s what IGN asked: “So when they find Cooper they are by Saturn again and they have these very advanced ships. So I guess I wondered: Did it take them many years to build the ships? If so, where did they get the resources? Was it on a new planet or on a dying Earth? Also, how did they survive on Earth long enough to build such ships? Or had they gone and colonized in the far reaches of space? In another galaxy? Had they found Brand and very quickly and impressively rebuilt their culture? And if they had gone and colonized, why were they at Saturn again? Right at that exact moment? What are they hoping to find there? If they had found Brand, then she would now be old too, wouldn’t she? Yet, Murph is suggesting that her father go find Brand so that they can build a colony together – which indicates that Cooper and Brand would still be the same age and compatriots. And that they would remain so once he found her in that small ship. Can you explain what’s going on in that scene? And just the science behind it?” Just the fact that someone has to ask a question this complicated shows how messy and thrown together this ending was. Nolan’s response starts with: “I’m happy to try — although I feel like it’s for the viewer to enjoy and trust that we spent and awful lot of time thinking about these things, as we did.” Of course. The old, “It’s up to the viewer.” That works when you’ve created a carefully thought out story. It’s a cop-out when you’ve belittled the audience by giving them a combination of psychobabble and nonsense for the past 30 minutes (you can read the rest of the interview here).

Am I being too harsh on Interstellar? Probably. But I believe Christopher Nolan should be held to a higher standard. He’s shooting for the stars here. So you need to be judged on what your goal was. The goal was a smart epic look at space travel. That’s not what we got. We got an imperfect movie with moments of brilliance, marred by moments of colossal laziness.

MOVIE RATING:

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

SCREENPLAY RATING:

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Cheat lines.” These are lines writers use to cover story problems in their script. Why didn’t they go looking for the greatest astronaut on the planet to head their mission in Interstellar? “We didn’t even know you were still alive.” Why in the world would they not think Coop was alive? Was there any evidence to this theory? What’s the harm in doing your homework and at least trying (it turns out he was only a few hours away!)? A well laid-out plot does not need the writer to constantly cover for it. Your use of a cheat line is indicative of bigger problems in your story. Instead of trying to bullshit the audience with a cheap cover line, go back and fix the underlying problem that’s causing you to cheat in the first place (in other words, it would’ve made much more sense for Professor Brand to show up on Coop’s doorstep and ask him to join his mission).

A Marvel superhero? Or a writer’s demons?

A Marvel superhero? Or a writer’s demons?

Screenwriting is in a funny place right now. The days of the huge spec sale are more a part of the past than the present. When you meet with managers and agents these days, they’re more likely to ask you about your latest TV pilot than your latest feature spec. As Marvel grows its brand, filling more and more of those precious movie slots with its bottomless pit of superhero characters, there’s more uncertainty than ever about what the industry wants. I mean it used to just be, “Write something marketable that you’re passionate about.” But that’s not enough anymore. You need a strategy.

With that said, most writers still make it into the industry the old fashioned way – hard work. They write something that speaks to them. It ends up being good enough for people to pass around. The writer gains fans, writes something else, gains more fans, builds his network, and sooner or later, writing assignments start coming his way. They’re small at first, but they get bigger as the writing improves. Some of these writers take the feature assignment career route. Some join TV staffs. Eventually, they become consistent working writers in the industry.

Now what they do from there – whether they stay at that low-to-middle working professional status or break into the elite level – is dependent on a number of factors. And that’s what I’d like to talk about today. I want to discuss “writer stages.” I read so many screenplays and most of the time after I finish, I think, “If this writer doesn’t change, they’re going to be stuck in this stage for the rest of their lives.” Part of being a good writer is recognizing where you’re at and working to fix your weaknesses. If you’re not willing to do this, stop writing now. You need to be a student of this craft, as well as your involvement in it, if you want to succeed.

STAGE 1 – THE ARROGANCE STAGE

WRITER NICKNAME – “THE CONTEST SUPPORTER”

The Arrogance Stage represents one of the most common misconceptions about screenwriting – that it’s easy. People see movies like “Need for Speed” and know, for a fact, that they can write something better. So they write a script, maybe two, and start hawking them around town, waiting for everyone to hail them as industry saviors. These scripts are the worst scripts I read, by far, as there’s a lethal combination of suckitude going on. One, the writer is using the industry’s worst movies as their bar. Therefore, everything is written to be only slightly better than that terrible movie they saw. The irony is that even though these writers THINK they’re better than the writers who wrote Need for Speed, they’re actually a lot worse. So they’re giving us an even suckier version of an already sucky movie.

And second, the writers have never studied storytelling on any level. It’s such an arrogant oversight that it actually infuriates the reader. It would be like wanting to be a surgeon but never studying the inside of the body. These scripts always lack original concepts, build, suspense, rhythm, character development, structure, or anything resembling what makes a story work. To add to the fun, there is so little respect for the craft, that the scripts are often riddled with misspellings, misused words, grammatically incorrect sentences, and more. I call these writers “Contest Supporters” because their scripts typically comprise of 75% of all contest entries and therefore fund the contest for the real writers.

To Break Out: To break out of The Arrogance Stage, you need to come to terms with reality. Your first scripts probably aren’t any good. They might be. But you need to operate under the assumption that they’re not. One of the biggest steps a beginner writer can take is admitting that being a professional screenwriter is hard. Once they do this, there will be a tectonic shift in the way they approach the craft. They will now put some real time and effort into the practice, and this should thrust them into Stage 2 in no time.

STAGE 2 – THE FOG-OF-WAR STAGE

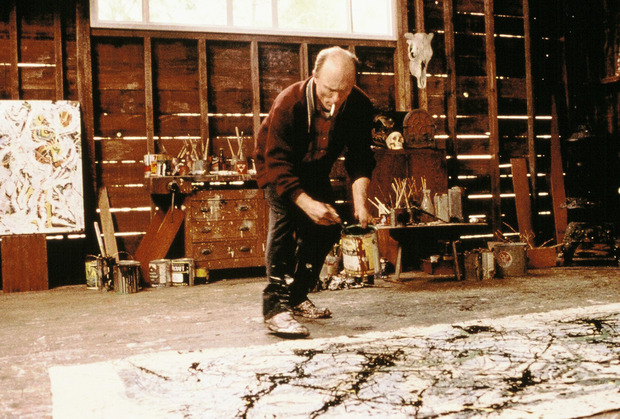

WRITER NICKNAME – “THE JACKSON POLLACK”

I call this the “Fog of War” stage because you rarely know where you are as a screenwriter while in this stage. How effective can you be if you’re not sure whether you’re 20 feet from the enemy or 20 miles? The commonality I see with these scripts is tiny bursts of good writing, followed by long chasms of bad writing. Why does this happen? Well, you’ve only just started learning the principles of screenwriting. So you know a few things, like what “3 act structure” and “character arc” mean, but since you’ve only written 2-3 screenplays, you’ve only been able to practice these principles 2-3 times. When have you ever perfected anything on the 3rd try? Likewise, you haven’t learned how to deftly hide exposition yet, how to come into scenes late, how to use subtext (etc., etc., etc.). Some of these things will come more naturally than others, but rarely can a writer nail them all immediately. I call these writers “Jackson Pollocks” because it feels like they’re randomly throwing paint against the canvas, hoping that the sheer earnestness of their intent will result in a masterpiece.

To Break Out: You need to embrace the study-bug in this stage. Read as many screenwriting books as you can afford. Read as many screenplays as you can find time to read (produced, unproduced, and amateur!). As soon as you learn something, go practice it. Study, read, write. Study, read, write. This stage takes time, because learning all the elements of good storytelling doesn’t happen overnight. But if you’re serious about screenwriting, this tends to be the stage that gives you your screenwriting armor.

STAGE 3 – THE STAGE OF DEATH

WRITER NICKNAME: “THE CYBORG”

I call this The Stage of Death because this is where many screenwriters, writers who have given years to the craft, disappear silently into the night, never to be heard from again. They’ll feel like they gave it their all, but couldn’t get over the hump for some reason, and so they leave. I have some strong opinions about these writers. Real writers never give up. They NEED to write. First and foremost, writing has to be FOR YOU. It has to be an outlet that you can’t stop yourself from doing, like a drug. Sure, as you get older and the complexities of life get in the way (i.e. supporting a family), you’ll have less time to write. But if you love this craft, you should never stop writing.

While Stage 1 scripts make me the angriest to read, and Stage 2 scripts are the most boring to read, Stage 3 scripts tend to be the most frustrating to read. That’s because by this stage in the game, the writer generally knows what they’re doing. They know how to tell a story. The problem is, they haven’t figured out how to tell a good story. A big part of the problem is that these scripts are driven too fiercely by structure and technicalities. Writers have learned what the books tell them to do, but they’re overplaying these elements, creating a robotic experience for the reader (hence: “The Cyborg”). These are the scripts that make the quarterfinals, maybe even the semifinals, of contests, and they show a respect for and an understanding of the craft. But they just don’t resonate. It’s almost like the scripts lack soul.

To Break Out: To break out of this stage, two things need to happen. First, there needs to be a change in philosophy. You know the technicalities of screenwriting. Now you have to go back to the mindset of a beginner. Instead of trying to meet technical checkpoints, start writing on “feel” again. Let your emotions guide you. Take a few chances. Break a few rules. The problem with writing a technically proficient script is that it reads like a technically proficient script. It’ll get you high grades with your professors, but low grades from readers who actually want to be moved. To get to the next level, you have to start emotionally connecting with the reader, and writing on emotion will help that. Now don’t get me wrong. You still want to follow the general guidelines of good storytelling. You just no longer want those guidelines to dominate your script.

The second thing that needs to happen is you need to identify your biggest weaknesses and work on them. If you suck at dialogue, you need to dedicate huge chunks of time to improving your dialogue. Finding your weaknesses requires getting HONEST feedback from others, not the “rah-rah” feedback that makes you feel good but keeps you chugging along at the same level. Locate where you suck and work to improve yourself.

STAGE 4 – THE TINY STAR STAGE

WRITER NICKNAME: “THE FRUSTRATED PROFESSIONAL.”

Getting to this stage is a big deal. You feel like you’ve crossed a major hurdle. You either have a manager or an agent (or both), secured a legitimate option or two (from a big production company) and/or have gotten assignment work. But for whatever reason, you still feel like an outsider, like a Stage 3. Your scripts aren’t landing on that prestigious Black List. Nor are they being fielded by the upper echelon of Hollywood – the people who can actually make things happen. What’s wrong?

Well, I can tell you what I see in the scripts themselves. These offerings are better than Stage 3 scripts. But upon reading them, I always feel like I’ve read them before. While the characters are well-written and the story is solid, I generally know what’s going to happen next, and therefore the story feels like it’s going through the motions. In some ways, these scripts are just as frustrating as the Stage 3s because you can see the potential for the story to break out, but it never does.

To Break Out: Three things need to happen to break out of this stage. First, take more chances. If you want to write something great, you need to take chances, because those chances are going to lead to the differences that make your script stand out against your competition. Taking chances is terrifying. But since the best stories are unpredictable, you need to make some unpredictable choices to write something great.

Second, you need to focus more on character. When I read the top scripts out there, it’s the characters that take hold of me, who make me feel something, who give me the warm and fuzzies. Rarely does a plot point touch me on an emotional level. So learn how to build interesting characters, how to build likable characters, how to build compelling relationships, how to arc characters, how to create problems between characters that need to be resolved. Learn how to make relatable characters and situations so that readers feel a connection to the people you’re writing. In short, focus more on character.

Finally, challenge yourself more. Most writers believe they only have a fifth gear. You actually have a sixth gear. And this is the gear that turns good scripts into great ones. Let me give you an example. Ben Ripley, the writer of Source Code, wrote a series of drafts of Source Code where an investigator comes in and investigates a time-altered train crash. He created the “5th Gear” version of this story. And he could’ve stopped there and sent the script out. But he decided to challenge himself, to push and find the element of the story that turned an average script into a great one. This led him to realize a more interesting take was to shift his main character from an impartial investigator to one of the passengers on the train. The next thing he knew, his script became one of the hottest in Hollywood.

STAGE 5: THE SUPERNOVA STAGE

WRITER NICKNAME: “THE TRUE PROFESSIONAL”

A Stage 5 script is a script that moves me. And you move people by creating compelling realistic characters going through universal problems that the average person relates to. Combined with a story that tackles strong universal themes (forgiveness, family, love, etc.) you can really move a reader. When you add an original concept and an unpredictable plot, you can count yourself among the best writers in the world. Of course, even Stage 5 writers are unsatisfied. I suppose the only thing that makes you happy at this stage is an Oscar. But you know what, if that’s your biggest problem in screenwriting? Is that you haven’t won an Oscar yet? I think you’re doing okay.

Now obviously, no two screenwriters’ journeys are alike. I’m not saying that every writer should be pigeonholed into one of these five stages. I’m saying that based on the scripts that I’ve read, this is where most screenwriters lie. But if that’s too complicated for you, here’s a simplified version of the plan: Treat yourself as a student of the craft. Always be studying. Always be reading. Always be writing. The second you think you’ve got it figured out in this business is the second you’re done. You should always be trying to get better!

Newsletter is here!: Guys, the Newsletter is OUT! Check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders if you didn’t get it. A new horror spec reviewed with Apocalypse Now as its inspiration and a lot of other fun stuff. If you’re not on the Newsletter list, sign up here!

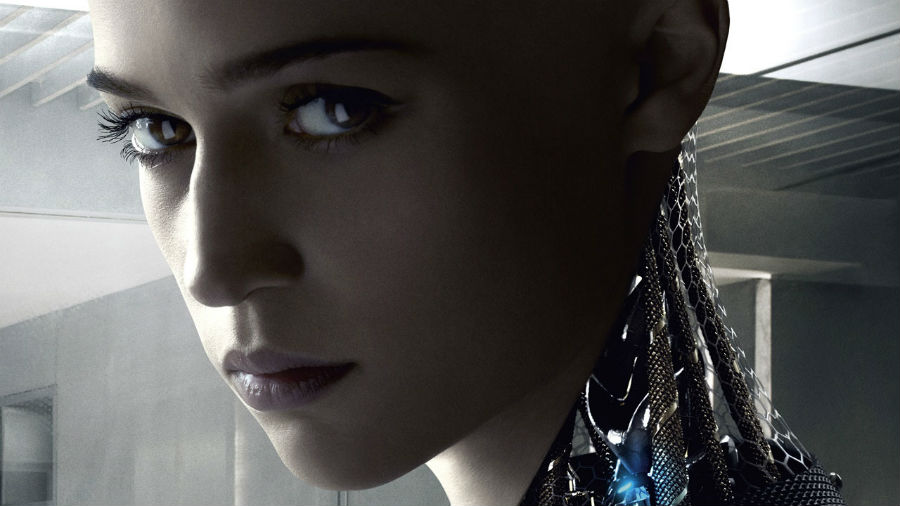

Genre: Sci-fi/Drama/Thriller

Premise: A billionaire programmer handpicks a young employee to spend a week at his remote estate and participate in a test involving his latest invention — an artificially intelligent female robot.

About: This will be the directorial debut of Alex Garland, who also wrote the script. Garland has been one of Danny Boyle’s right hand men, writing The Beach, 28 Days Later, and Sunshine. He penned the dark drama adaptation Never Let Me Go a few years ago, most recently scribbled the cult hit “Dredd,” and has also written drafts of Halo and Logan’s Run. In other words, he’s big time. This script sold last year. (Addition) This review originally appeared in the newsletter last year. Off of the cool trailer that debuted last week, I decided to post the review on the site.

Writer: Alex Garland

Details: 114 pages – undated – version “.08” (which leaves this draft legally over the limit)

Garland’s been hit or miss with me. He hit with 28 Days Later and Dredd but wrote two movies that utterly fell apart in their final acts in Sunshine and The Beach. I’d almost rather watch a bad movie from start to finish than watch one that starts well and then collapses. Then again, Boyle was guiding Garland along during those films, so maybe it was him who screwed them up.

I decided to read Ex Machina due to its “spec-friendly” nature. It’s a small character driven film hidden inside a sci-fi concept. The idea with any screenplay is to draw them in with the flashy premise, then make them stay with your characters.

Ex Machina introduces us to computer whiz Caleb, a young man who cares more about beating his personal 24 hour coding record than he does trolling the local Starbucks in hopes of convincing an artsy chick to give him her number. Caleb is currently coding a program that appears to be for a contest, a contest he’s desperately trying to win. And to his amazement, he does just that.

It’s only once we’re in a chauffer-driven limousine that we realize what this prize entails. Nathan Bateman, a young eccentric billionaire, has awarded Caleb one week at his home – to stay and hang out – though the exact reason for the stay hasn’t been revealed yet. As Caleb impatiently asks the chauffeur how long it will be until they get to the estate, the chauffeur calmly responds, “We’ve been driving through his estate for the past two hours.” Yes, Nathan is that kind of rich.

Nathan’s also kind of an asshole, and a douchebag, which we pick up on pretty quickly. He lives off in his own little Hearst Castle Wonderland, completely out of touch with reality. Of course, Nathan’s making so many amazing things happen, it doesn’t really matter. He believes he’s just created the first fully conscious artificially intelligent robot. That’s why Caleb’s been brought in, to test this creation. Which is how we meet Ava.

Ava is a beautiful piece of machinery that doesn’t look anything like a piece of machinery. She’s a flawless perfect stunning blonde woman who just happens to be made up of wires and circuit boards. But you wouldn’t know it by talking to her. She’s calm, clever, even funny. Caleb takes to her immediately. Maybe a little too much.

What follows is a series of tests that Caleb puts Ava through to determine if she’s just programmed to feel things or if she ACTUALLY feels things. For those of you who aren’t super-geeks who have read all the books on the Singularity, creating a robot that’s conscious of itself is basically the Holy Grail. And the more Caleb talks to Ava, the more convinced he is that Nathan has found this Holy Grail.

Ahh, if it were only that easy though. Things start to get messy. Caleb begins to suspect that Nathan is fucking with him. He just can’t figure out why or what about. He also begins to have feelings for Ava, something that would’ve sounded ridiculous at the start of all this, but now seems quite natural. He also learns that Ava hates her creator and would do anything to get away from him. Would Caleb…could Caleb perhaps…help her escape? They could even run off and be together. This becomes the plan as the story pushes towards its final act. That is until Caleb starts to wonder if Ava is playing him too.

Ex Machina reminded me that there are two ways you can start a screenplay. You can go the “introduce the main character’s world first” route, where you show Luke’s life as a frustrated wind farmer who wishes he were a star fighter battling the Empire. This is the method taught in most screenwriting books. The other method is to “jump right into it.” In this approach, you skip all those character establishing scenes and throw us into the story, as they do here with Ex Machina. I mean we have a single scene – Caleb writing code – before he’s off to meet Nathan.

There are pros and cons to each. In the “introduce the world” scenario, we get to know the character better. We understand his world, his backstory, his hopes, his dreams, his flaws. Because we know him better, we’re more likely to relate to him and root for him. The problem with this approach is that it can be boring. Scripts need to move and if we’re sitting around for ten scenes just “getting to know someone,” we’re probably going to get bored.

The “jump right into it” route takes care of this issue. We’re entertained right away so we don’t need to worry about that pesky drawn-out first act. The problem with this approach, of course, is that we don’t get to know our character as well, which means you run the risk of the audience not giving a shit because they don’t feel close to the person leading us through the journey.

A common solution is to quasi-combine the two options. For example, The Matrix throws us into the story right away, but then takes a step back and introduces us to Neo’s world. Or, you can throw us into the story right away, like Garland does here, and try to slip in bits and pieces of your protagonist’s life where you can. Which is hard because the best way to set up a character is to see him in his environment. But it can be done. For instance, Garland uses this scene of anticipation where we’re driving to Nathan’s mansion to slip in a few details about Caleb’s character. The point is, it’s tricky. But as long as you understand the challenge, it’s possible to overcome it.

As for the rest of the screenplay, I thought it was good, but not great. I loved the use of the “Great Gatsby”-like mystery box of “Who is Nathan?” I was pumped to find out. I also enjoyed the initial scenes between Caleb and Ava. But as the script went on, it started to feel like I was ahead of the story. What pulled me into this script were the mysteries. And those seemed to be answered fairly quickly. Afterwards, we’re left with some compelling questions and interactions (what is consciousness? Can a man fall in love with a machine? Is this all a game?) but the script was never as effective as when it had those mysteries going.

This is something I’ve noticed in a lot of scripts. Writers include early mysteries because they’re easy to create. Everything about the world is new, so it’s not hard to say, “What’s this person hiding?” However once they’ve got you hooked, they move on and focus on other things. But it’s kind of like hooking a kid on candy and then trying to feed him broccoli. The kid doesn’t want broccoli. They want candy! It is harder to introduce mysteries as the story continues, but it’s worth it to try. I know I would’ve liked an extra mystery or two in that second and third act.

Despite the eerie tone of this man cut off from society left to roam an immense mansion where he’s being watched by numerous cameras, his only interaction being with this weird creepy billionaire and his robot, the story doesn’t quite have the endurance to make it to the finish line. I think what it needed was another subplot, a little more going on inside the house, and a solid mid-point shift. Remember, mid-points are where you throw something at your audience that changes the story up a little so the second half doesn’t feel like a repeat of the first half. I didn’t see that here, and the story suffered a little as a result.

Still, the writing was strong, as you’d expect from someone as accomplished as Garland, and it passed the ultimate story test: Did I want to find out what happened in the end? The answer to that question was yes, and for that reason, it’s worth the read.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The script needed another mystery or two. And I think I found an opportunity that Garland missed. When we first meet Nathan, he gives Caleb a security card that he explains will let him into some rooms, but not all of them. What Garland probably should’ve done was highlight one specific room that was locked that Caleb was never allowed to go inside. I’ve never seen this device NOT work before. You use that room throughout as a mystery box, with the audience desperately anticipating what’s inside. That would’ve helped here, as the script ran out of mysteries too early.

Read as far as you can and tell us which script you liked best in the comments!

TITLE: The City

GENRE: Futuristic thriller

LOGLINE: An illegal artist hides in a nuclear wasteland to avoid a death-sentence but is forced back in an exchange to save his friends who have been kidnapped.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’ve spent a bloody long time on this script – over 5 years – and it’s completely different now to what it was when I started, as it should be. The story at the crux of it remains the same, and that’s what it’s all about. It’s a small story in a bigger world… As Jim Jarmusch said, “I’d rather make a movie about a man walking his dog than about the Emperor of China.” Anyway now that it’s “done” I need to get it out there, and I’m at a bit of a loss as to how to do that! Sure I can send out script queries but I feel this needs a real read and review – good, bad or otherwise. I’ve had friends and friends of friends read it for me, but they’re probably just being nice when they tell me what they think. I want professional words of wisdom because if there is one thing I can do it’s take them, take advice, hit notes, improve, and ultimately, from this, write in a way that will help me progress my career. This script has been a part of my life for so long I’m feeling pretty lost right now! This feels like a handy next step…

TITLE: They Ate the Horses

GENRE: Adventure/Horror

LOGLINE: A century after mankind’s near extinction, a daring teen eludes her overprotective father, risks an adventure to a neighboring town, and quickly discovers slavers are the least of her worries.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Hey! Hey everybody! Another post-apocalyptic wasteland! Someone tell the DP to get the “grey” filter ready! You may notice that this is sarcasm. Glowing sarcasm, in fact. We’ve populated this world with likable (and not-so-likable) characters, danger, humor, and yes, even color. Come for the colorful take on life after (most) humans, stay for the ridiculous twist. I hope you have as much fun reading it as we did conceiving and writing it.

TITLE: The Benefactor

GENRE: Psychological Thriller

LOGLINE: A young widow discovers her husband’s accidental death is the latest in a series of murders-for-profit reaching back more than a decade.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This is based on my published novel. In its review, Mystery Scene magazine described the book as “a story Hitchcock would have approved of.” Exactly what I was striving for.

TITLE: PARKING ENFORCEMENT

GENRE: Buddy Comedy (Step Brothers meets 21 Jump Street)

LOGLINE: When two bumbling brothers get their shot at a badge after twenty years in Boston parking enforcement, they will uncover a police conspiracy forcing them to go after the very people they’ve spent their entire lives wanting to be a part of.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: After failed attempts at recognition with less commercial fare, this is my first stab at a highly structured, broad commercial comedy. The initial inspiration for this came from a single question: what if The Departed was a comedy? Boston is always used in a very serious way where the deep roots of cops run for miles, so I wanted to take that aspect of it, flip it on its head for a comedy (a la The Heat) and ask a secondary question around, what if two people who had the badge in their blood wanted to be, but couldn’t? And, then finally, what if they were completely opposite brothers? I’d love to better understand what works here and what doesn’t from a story perspective. To date, this is the most structured and outlined script I’ve ever written.

TITLE: Broken Vessels

GENRE: Body-switching

LOGLINE: A New York City policeman tracks a serial killer through 700 years of dead bodies to find the secret to an immortal curse.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’ve been a quarterfinalist in the Nicholl three times in four years (with two different scripts). I was a semifinalist in the Big Break the one, and only, time I entered. Frequent site contributor walker listed one of my scripts (not this one) as the best amateur script he’s ever read. I wrote this script with actors in mind. It is Oscar-bait for the Denzel Washington’s and Ryan Gosling’s of the acting world. Plus, you’ve said you are always looking for the perfect body-switching script. What if this is it?

Beyond that: At 40, I am stuck in a middle management job that requires me to get up at 3:30 in the morning and work 11 hours a day 6 to 7 days a week. I have a daughter at NYU, the most expensive school in the country, and my wife is now expecting our fourth child. I know I can write and, up until now, I have been willing to wait for my chance. Circumstances have conspired to put me in a more “Kyle-Killen-when-he-wrote-The Beaver” frame of mind. Were your site to bring that chance to me, I would not forget it—the way others that got their break from your site seem to have forgotten it.

At 29, Adi Shankar is one of the hottest young producers in town and one of the few guys who isn’t afraid to produce risky R-rated material. His credits include The Grey, Dredd, Lone Survivor, and A Walk Among The Tombstones. He’s also releasing one of my favorite scripts, The Voices, next year.

Shankar’s counter-culture approach extends to the web as well, where he’s produced the short film, “Punisher: Dirty Laundry,” starring Thomas Jane and Ron Pearlman, and “Venom: Truth in Journalism.” His newest offering is the animated dark comedy mini-series, “Judge Dredd: Superfiend,” which you can go watch right now!

SS: Before we get into writing, I’ve always admired your ability to make these risky R-rated films in an industry that’s typically afraid of that space. How do you pull it off?

AS: Most companies egregiously overspend on overhead. I believe in a lean, tight-knit team, and it allows me to be cost effective in all my decision-making and affords me the financial freedom to make “riskier” films.

SS: Okay, moving on to my bread and butter. I always talk to writers here on Scriptshadow from a writing perspective. But producers see the craft differently. From your side of the wall, what advice can you give writers just starting out?

AS:

1. When starting out, don’t be discouraged by people with the “9 to 5” jobs. They are the ones who urge you to “be realistic,” goad you as you attempt to understand yourself, and bring you down during your sporadic, minor, yet intangible victories. Take solace in the fact that these “9 to 5-ers” will get their minds blown when they see Katy Perry (or equivalent) at a restaurant one day and it will become the single defining moment of their lives, while you are attempting to add to the discourse of the culture.

2. Write every single day. If you don’t, writing will always just be your hobby. (Note: This doesn’t mean quitting your job)

3. You should read 200 “great” professional screenplays before you start writing so that you know what you are aspiring to be. The resources (scripts, interviews, trades, etc.) you have access to today as a beginning screenwriter are unparalleled and were only available to previous generations by becoming someone’s bitch. For the first time, you don’t even need to live in Los Angeles to be a screenwriter or to have your work read.

4. Follow the plethora of online recourses that weren’t available to past generations i.e Blacklist and the tracking boards, to see what’s selling, what’s getting heat and not selling, what’s getting acclaim, and what’s getting acclaim but not selling. This will inform your understanding of the marketplace and the business of screenwriting.

5. Write and produce for the Internet. It blows my mind that more people aren’t attempting to build a web footprint. Check out NEXT TIME ON LONNY it’s simple, smart, funny and is a blueprint for anyone who aspires to create.

SS: What about writers who are closer to the mid-level? These might be writers on the verge of breaking in or who have just punctured the lower levels of the industry. Any advice for them?

AS: The biggest misconception you have to psychologically fight is this idea that once you cross a certain imaginary threshold in your career you’ll feel “made.” You’ll never feel truly “made.” While, like any rote skill, things do get easier over time, you struggle consistently at any level and actually feel more not less pain at every higher rung on the proverbial ladder.

This industry is convoluted and hard for everyone: Whether you’re a novice writer or Robert Towne, a beginning actor or Russell Crowe, an assistant at the mailroom or Stacy Sneider there is always arbitrary red tape, infuriating walls built by insecure middlemen, and some asshole that just wants to fuck you over for the sake of fucking you over. You are constantly living with a damoclean sword over your head and a lottery ticket in your hand, one bad decision away from being black balled and one great sentence away from becoming the next big thing.

SS: Everybody’s trying to get their idea/script/project to the guy who’s able to say “yes” and the movie is greenlit. You’re occasionally that guy. In your best estimation, what do you need from a screenplay to give it that green light? What makes you say “yes?”

AS: Two things need to happen:

1. I need to respond to it creatively. (Note: I detest the routine and respond to material that is unconventional).

2. The market needs to respond to it financially.

As you can imagine 1 & 2 are almost always at odds with one another.

To be specific, by the “market” I don’t mean the movie-going public. Unless you are operating at the highest of levels (aka the Chris Nolan, Spielberg, JJ Abrams level), producers/directors don’t make movies for audiences, we make movies for distributors, and are beholden to what distributors believe audiences want (read: the last successful movie).

Second only to the inability of distributors to match a prospective customer with a specific product in a cost effective manner, the biggest problem that our industry needs to solve is the issue of access. Information is a commodity to the detriment of the business.

So my advice to writers: Figure out what the market wants and write the best version of that as quickly as you can before the market changes. For example, in 2008 it was quirky indie comedies, in 2010 it was $25-30 million dollar action movies, in 2012 it was $3 million dollar horror movies. Pretty soon the $7-12 million range, which for years had been the “no mans land,” is going to be the independent sweet spot.

SS: This leads me to a question I’ve always had. This industry is actor and director driven. If you get a big actor or director attached to your script, the project has a much better chance of getting made. So as a writer, should I be trying to find ways to get actors and directors to read my script so they’ll attach themselves, THEN come to you? Or should I come to you first and let you use your relationships with actors and directors to put that project together?

AS: It depends. I prefer STD free scripts, but sometimes if the attachments are so great then everyone is obviously going to pay more attention. Again, it depends on the producer and the genre of the script.

By and large I’ve found attachments for the sake of attachments to be a detriment. I once read a script that I thought was great but the manager insisted that a much hated director had to be attached to direct. That manager ultimately screwed the writers by making their very makeable, highly marketable script instantly un-makeable due to a bogus attachment. The marketplace moved on and the window of opportunity to make the film passed.

Also, when you’re attaching someone, realize that you are getting in business with the person, that person’s reputation within the industry, and reputation with the potential buyers for your project, not their credits.

SS: You sell your movies to many foreign territories, which is a way to fund your movies (or most of them) before they even get made. Film is becoming more and more of a global business. Should screenwriters be accounting for that in their screenplays? Should we be writing differently? How does one write for a “global audience?”

AS: Don’t worry about this. Just try to tell a really great story. The more you get caught up in trying to retrofit a human story into something that will “sell globally” the more you risk diluting your material.

SS: You were telling me about a project awhile back, an idea you came up with. And you said you went out and found a writer for that. How does a writer (say, a writer reading this right now) become the person you call to write your movie? How does he get in that room with you?

AS:

Step 1: In that particular instance the writer had written the last movie by the director whom I was developing the idea with. The brutal reality is that writers almost always get hired for an assignment because of a working relationship.

Step 2: When I call writer’s representatives, it’s preferable that they be “user friendly.” I’ve passed on working with so many talented writers because I thought their agent or manager was a cheese dick and was going to cause problems down the road.

Best blanket advice I can give to an up-and-coming writer:

Find a talented director at “your level” and partner with them and become “their writer” and start operating as a team (See: Wigard, Adam & Barrett, Simon). So many talented directors are in dire need of writer/producers to execute their wonderful ideas and more importantly for a creative partner who isn’t a cornball producer trying to pull a silver dollar out from behind their ear. This journey in 2014 is now too complicated and frankly impossible to do alone, so build a collective.

To be a douche and quote myself:

“Hollywood is undergoing a massive decentralization right now, caused by the ongoing collapse of the studio system and the rampant greed of the 90’s. It means that collectives of people who can consistently and autonomously deliver a product will have an advantage. They will help you sift through all the crap Hollywood throws at you, and more importantly give you the kind of creative autonomy that today’s non-celebrity filmmakers can only dream of.”

SS: Is it important that a writer be “good in the room” with you? Do you have to feel a chemistry or a certain energy and knowledge from them to work with them? Or do you only care about how good of a writer they are?

AS: Being good in the room doesn’t matter. I don’t want the guy who sells me the car to design and build the car too. I’m also not looking for a friend, girlfriend, roommate, drinking buddy, flip cup or beer pong partner. Humility, writing skills, and general insight about life that can be retrofitted into a screenplay are all that matter. I do meet many writers who are whiney and unloved and complain about “how unfair the industry is” and I generally want to bitch slap them … so don’t be that guy.

SS: I ask a lot of producers what they want from a script, and they almost always say, “I’m just looking for something great.” Is it really that easy? Or are there more factors involved?

AS: It’s that simple. We just want great material. Great material will attract a great director and that package will attract “bankable” (note: as an actor myself that word pisses me off) actors. It will make distributors fight over the distribution rights. Give me SOURCE CODE and I’ll produce and deliver you a finished film via text message faster than you can say Punisher Dirty Laundry.

SS: Does a writer need an agent for you to read their scripts? If you do receive scripts outside of agents, where do they come from?

AS: It’s a legal grey area. I desperately want to discover a great script from under a rock but legal reasons make it challenging.

Traditionally, success in this business has been proportional to one’s access to information. In their inevitable next evolution, online screenplay resources like ScriptShadow, Trigger Street, and Blacklist are very shortly going to revolutionize the way producers/actors/directors access material and democratize the green lighting process.

Before the Internet, an agent had the ability take a script off the shelf and present it as brand new. Tracking boards made the spec market efficient. Blogging made it possible for one to dissect material and allowed the industry to congregate behind risky but great material. The next tectonic shift will be numerically driven and force an egalitarian more “crowd sourced” process to the chaotic status quo.

On the issue of agents, keep in mind that reps are useless unless you have a career spark. To be clear, it’s on you at every juncture in your career to create a spark for yourself. If you are unrepped and looking for your big break right now the web stuff is the best platform to create a spark. What reps are really good at is turning a spark into a flame and the best reps will help convert that flame into a forest fire (see: Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper).

SS: Finally, we all know Hollywood prefers intellectual property that’s already proven. Since all screenwriters are poor and can’t afford to buy flashy intellectual property, what can they do to compete with these guys?

You bring up an interesting point. In television, the writers are the producers. This should be the case in the movie business as well, as it would eliminate a lot of the infrastructural problems we face.

A trend I’ve noticed is that once writers become deemed “professional writers” many take the mentality of “I need to be paid to write.” While I can sympathize, the fact of the matter is great screenplays are the lifeblood of this industry. If you have a great story that must be told … fucking write it.

It doesn’t make sense to waste time waiting for some jerk off producer or studio to “buy your idea.” Own it, control it, and if you really are that good you may have just written the next DALLAS BUYERS CLUB, PRISONERS, or LOW DWELLER (OUT OF THE FURNACE). Every major movie star and every major director needs a “next movie” and even those we have deemed gods at the moment are beholden to access to great material and are at the mercy of those who control it. Unencumbered scripts are easier to make.