Search Results for: F word

The first Logline Showdown winning script of the year!

Genre: Dramedy

Winning Logline: An ambitious journalist for a cheap tabloid returns to his hometown where he’s forced to cross previously burned bridges with friends and family while investigating claims of a giant frog creature terrorizing the town.

About: Thanks again to Scott for doing all the hard work tallying votes for January Logline Showdown. Frog Boy pulled in 24 and a half votes, which was 32% of the vote, besting The Rhythm Police at number 2, which received 17 and a half votes (23%).

Writer: Zach Jansen

Details: 101 pages

For a while there, I didn’t know who was going to win. Rhythm Police was getting a lot of love. That would’ve been fun to review. But you know what? I thought The Glades (3rd place – 16 votes) was going to win the weekend when I put the loglines out. That one felt the most like a movie to me. But I’m kinda glad you guys went with something unique. That gives me hope that not every movie produced going forward is going to have iron man suits in it. Let’s see how the first winning logline of the year turned out…

20-something James works in the big city. Well, if you can call “Cleveland” a proper city. They do have the only lake in the United States that catches on fire. Sorry, Midwestern in-joke there.

James works at one of those tabloid papers that need to fit aliens into every headline. Personally, I don’t know why that’s considered “tabloid.” Aliens are real. It’s been proven on Twitter. Duh. Sorry, I’m getting distracted again.

After pissing off the city mayor, James’ boss wants to get him out of town and, by pure chance, there’s a story that would be perfect for their paper in James’ hometown – One of the city’s workers was recently attacked by a giant frog.

James hems and haws because he hates his small podunk town but agrees to go there when his boss threatens to fire him if he doesn’t. Immediately upon arrival, James runs into all the usual suspects – the reformed town bully, the angry ex-girlfriend, the father he can’t stand. But James is a professional. He’s not here for drama. He wants to solve the Frog Boy case. Or, more precisely, he wants to prove it’s nonsense.

Upon doing some research, James learns that the Frog Boy sightings date back decades, specifically around the town’s central lake. Could this frog boy phenomenon be true?? And then there’s the bigger question in all of this: Is anything true? James became a skeptic all the way back when he was a kid and decided there was no God. Which is why he and his religious father don’t talk anymore. James finally teams up with his ex to get the definitive answer on the frog. But what he ultimately finds just may ribbet his whole reality.

It took me a long time to understand why investigations were perfect storytelling vessels. The goal is built right there into the premise! Your main character’s activity is built right into the premise! This is why they can make 50,000 TV shows about cops. It’s because the cops always have an investigation, and those investigations effortlessly power stories.

But where the real fun in investigatory storytelling comes from is when you go off-road. You don’t just give us another murder to investigate. You have some fun with the investigative format. Which is why this logline was chosen. It gives us an investigation we don’t typically get to see. It’s different.

But even if you have a powerful engine pushing your story along, you still need some exciting sights and stops along the way. I didn’t see enough of those in Frog Boy.

One of the most common mistakes I see in screenwriting is assuming too much familiarity on the reader’s end. You think they know what’s going on but you haven’t given them enough information for them to understand the scene. Here’s an early example of that in Frog Boy…

Jansen assumes we know that the boss character is thinking about sending him to his hometown for this frog story. But I don’t know this boss character. I don’t know what he knows about the frog story. I don’t know that he knows James lives in Loveland. I didn’t even know James lived in Loveland at this point in the story.

So when we come into the scene with the boss asking James where he lives, we’re confused. The only indication of what’s going on occurs in a parenthetical (“realizes”). But I didn’t catch the meaning of that at first. I had to re-read the scene to understand it.

All of this could’ve been cleared up by simply being in the room with the boss as he’s looking at the frog story online before James walks in. Now we know why he’s called James in and we can enjoy the process of the boss yanking him around.

Too often, we writers assume the reader knows more than they do. They don’t know anything UNLESS YOU TELL THEM. Keep that in mind every time you write a scene, ESPECIALLY early on in the script when you hold TONS MORE information about your story than the reader. Those first 30 pages are when they need you holding their hand the most.

There were also some mistakes made on the dialogue end. Dialogue isn’t always about the words being said. It’s about the situation you create around the words to give them the most impact. In the middle of the screenplay, James goes to jail. He has no other choice than to call his father, whom he despises, to get him to bail him out.

The dad comes, bails him out, and on the car ride home, the dad starts making demands. “I want you to stay at home while you’re here instead of at the hotel.” But the demands hold no weight because the dad HAS ALREADY BAILED JAMES OUT.

This conversation would’ve had a lot more impact had the dad visited James while he was still behind bars and made the demands THERE. Now, the demands actually hold weight because James has to decide which is worse, staying in jail or staying with his dad. These are little things but they add up. They make a difference. There were several more scenes in the script where there was zero conflict or zero stakes so the conversations just sat there.

What the script does get right is its tone. It’s a fun little screenplay. It’s a fun investigation. It’s got charm. Some of the scenes of James investigating the loonier people in town made me giggle. Here’s an early exchange between James and his former bully from school.

The script had this dependable spine that always had you smiling, which stemmed from its quirky investigatory center. And it even had some character relationship depth. I thought the stuff with James and his dad about faith, which tied into the frog storyline nicely, was solid.

I would even react positively to anyone who asked me what I thought about the script. I would say, “It was cute.” That’s positive, right? But I just had this conversation with a writer the other day, who also had a cute script. I reminded him, “Cute is better than average. Cute is a lot better than ugly. But cute isn’t hot.” In the ultra-competitive world of screenwriting, cute gets you a smile. Hot gets you a date.

How do you make Frog Boy hot? The best way to make a script like this hot is to make it darker, weirder, or funnier. “Funnier” can be tough because it’s hard to write a consistently LOL script. But you can always make creative choices that are darker and weirder. You have a Frog Boy. You can push that into some risky areas.

But, in fairness to Jansen, I don’t think he’s interested in that. He wants this to be light. And movies like this *do* get made. This reminds me of a lot of films such as Welcome to Mooseport or Swing Vote. I think I imagined something a little wilder, though, something weirder. Which is why I can’t quite recommend the script. But it was right on the cusp of “worth the read.”

Script link: Frog Boy

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Show and Tell. When it comes to your hero’s flaw, you want to use a two-pronged approach. The first thing you want to do is SHOW the flaw. So if your hero runs away whenever things get tough, write a scene where we see him run away when things get tough. Then, what I encourage screenwriters to do, is to add a flaw “tell” somewhere in the script. For a variety of reasons, readers may not pick up on the flaw when you showed it. So you can tell it to the reader as well, just to make sure everyone gets it. Here, we have our “tell” moment when James is talking to someone from town to get information on the story.

The problem in Frog Boy is that we never got the SHOW. We only get the TELL. And when you do that, the reader always feels it less. So make sure you first show us and only then, later, tell us.

Is the worst logline on the 2023 Black List its best script??

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from Black List) A married man takes his girlfriend on a romantic getaway to a villa. There is a swimming pool.

About: This script was on the Black List with 8 votes. The writer, Evan Twohy, had a script on the Black List a couple of years ago called Bubble & Squeak. The only thing I remember about it is that it was weird.

Writer: Evan Twohy

Details: 101 pages

Since we’ve been having so much fun with loglines all weekend, I thought, “Why not keep it going?” Just like America’s football fans can’t get enough Taylor Swift drama, I can’t get enough logline drama!

Today’s script had the single worst logline on the Black List. And yet, several of you read the script and told me it was great! Hence, I wanted to provide the “loglines don’t matter” crowd with some ammunition going forward. It’s finally time to review “Roses,” aka “Swimming Pool Script.”

51 year old Martin says goodbye to his wife, Justine, as he heads off on a work trip for the weekend. At least that’s what he tells Justine. We see him drive up to Northern California and pick up the 28 year old naive Rose, who’s quickly falling in love with Martin. Martin then drives her to a big Air BnB cabin in the forest.

After the two make love, Rose decides to go swim in the poorly cared-for pool, which has a greenish grime layer over the top of it. The two later head to sleep when Martin is woken up at 3 in the morning to a sound outside. He grabs a working old gun from the wall of the mansion and heads out, only to find Rose inexplicably swimming laps in the pool.

He asks her if she’s crazy, only to hear Rose reply from behind him. He turns and sees a second Rose, aka Original Rose. The Rose coming out of the pool is Rose #2. Savvy moviegoers will figure out what the script tells us later – this pool duplicates anybody who swims in it.

Martin is stuck between a rock and a hard place. He’s freaking the heck out but he can’t exactly call the cops, since his weekend soiree with a younger woman will get back to his wife. Eventually, Rose #1 talks him into sleeping on it. And the next morning, they try to figure out what they’re going to do.

Soon, it’s apparent that Rose #2 is different from Rose #1. Rose #1 is head over heels in love with Martin and would trust her life to him. Rose #2 is only in it for the fun and finds Martin annoying and dumb. If it was up to her, she’d end this affair tomorrow. Because of this, Martin covertly takes Rose #2 on a walk deep into the woods and shoots her dead. Problem solved.

Well, not really. When he gets back, there are five new Roses with the original Rose. And worse, they’re starting to look different. For example, one of them has a nose growing off of their neck. It turns out the Roses love swimming in the pool. And, despite his attempts to stop them, they keep swimming, and keep duplicating, with each new iteration less human. Once the Roses finally have a big talk about Martin, they realize he’s one of the worst people ever. Which only means one thing: They have to eat him. Will Martin be able to escape? Or will the rapidly expanding Roses consume him?

One of the common issues I find in amateur screenplays is that the writers come up with a unique idea but they don’t do enough with it. For example, they might come up with an idea about time travel, yet their entire third act has nothing to do with time travel. When you come up with a unique idea, your job, as the screenwriter, is to exploit the heck out of that idea. You want to milk every last drop out of it. That idea is the selling point of your entire movie. Why would you avoid it?

If you want to know how to exploit an idea to its fullest, read this script.

This script is the blueprint for concept exploitation. At the end of the first act, we have two Roses. By the midpoint, we have five Roses. Within ten more pages, we have 30. Ten more, we have 50. By the third act, we have 100. By the climax, Martin himself is multiplying.

In other words, whenever the script needed to evolve, it went back to its hook – the swimming pool that clones whoever goes in it. Whenever you’re facing an issue in your own screenplay that you can’t find a solution for, exploiting your concept is usually the answer. So, if your movie is about a guy trying to start his chocolate business (Wonka), and you’re not sure what to do with your climax, you should probably lean into… drum roll please… CHOCOLATE. Which is exactly what they did. Wonka is tossed, by his rivals, into a vat of steadily rising liquid chocolate to die.

The genius of this script is that it never stops leaning into its unique premise. It keeps going back to that swimming pool well. And the writer has a lot of fun with it. It isn’t just that Rose keeps getting cloned. It’s that her clones get cloned and each one comes back a little less human. So these new Roses we’re getting become gnarlier and gnarlier. In other words, the writer isn’t mindlessly milking his premise. He’s CREATIVELY milking it.

So, what does a non-exploited version of this premise look like? We’ve seen it before. It’s if Twohy would’ve stopped at two Rose clones. You can write that version. And I’m not even saying that version of the script would have been bad. But it wouldn’t have been as fun as this one.

The only issue I have with this script is that I’m not sure what it’s trying to say.

There was this interesting moment about 40 pages into the script where Rose 2 reveals that she doesn’t have that naivety that Rose 1 has. She’s more skeptical of men and their motives. Twohy seemed to be exploring the multiple voices in our heads that are always fighting each other during the life decisions we make. I thought he was going to continue down that road with each new iteration of Rose that came out of the pool. But that never happened. They became more like a hive mind determined to eliminate Martin.

It’s a common issue writers encounter when writing a screenplay – they can either lean into the aspects of the script that create more of a theme, or lean into the aspects of the script that create more of a fun story. Rarely are you able to do both. But this script ends up being so wild and fun by the time we reach the third act, I think Twohy made the right choice.

So does this answer the age-old question once and for all? Loglines don’t matter? I’m afraid to say it does not. Because I never would’ve read this script based on the logline and I don’t think anybody else would’ve either. The script was read because the writer had a previous high-ranking script on the Black List that got a lot of reads and developed a lot of fans for the writer. So they were eager to read anything he wrote, regardless of the logline. You, as the unknown screenwriter, don’t have that luxury. You need to earn it first. So pick a great concept and write a great logline. :)

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If I didn’t make it clear enough in the review, EXPLOIT YOUR CONCEPT AS MUCH AS POSSIBLE. Every creative decision you make in your script that isn’t derived from your unique premise, means you are creating characters and scenes THAT COULD BE IN ANY MOVIE. The goal is to create an experience that can only be enjoyed IN YOUR MOVIE. So lean into your premise as much as possible!

The box office is so dead right now that the biggest story in Hollywood is Sydney Sweeney doing Hot Ones and the 500 memes that have already been born out of her episode. Of course, you’re not going to get any argument from me. The more Sydney Sweeney on the internet, the better the internet becomes. That’s indisputable math. I checked with Neil deGrasse Tyson.

I am happy to see that The Beekeeper is still buzzing along, though. The underrated flick with the honey-sweet script dipped just 17% from last week to reclaim first place. That’s good news for screenwriter Kurt Wimmer, who may have laid claim to the stash that every screenwriter dreams of – a franchise.

But since there’s nothing else to talk about on the box office end, I thought, why not jump right into “Why Your Logline Didn’t Make the Cut?” This Thursday is reserved for a “Start Your Screenplay” post. Friday we’ve got a review of this weekend’s Showdown winner. Today is about teaching writers the value of a strong concept and logline.

Title: Safe Space

Genre: Thriller

Logline: From her bird’s eye point of view, an alcoholic crane operator on probation races against time to piece the clues together to prove a murder happened in an apartment before she becomes the killer’s next victim.

Analysis: I actually thought this logline had potential. It’s one of the more unique contained thrillers I’ve seen. But this is a great example of how the message of a logline can be lost due to the absence of a few words. I *think* this all takes place in the crane. But the logline doesn’t make that clear. “From her bird’s eye view,” is just vague enough to make us wonder. When it comes to loglines, don’t get cute. You need to actually say: THEY’RE IN THE CRANE THE WHOLE TIME. Cause otherwise it’s too easy to misinterpret it. I’d also want to know why they’re in the crane the whole movie and why that’s relevant. These things are not clear enough in the logline.

Title: Bunker Mentality

Genre: Zombie comedy

Logline: A group of high-ranking government officials struggle to manage the emergency response – and their own survival – after they accidentally lock themselves inside a secret military bunker at the outset of a zombie apocalypse.

Analysis: This one has a similar issue. It’s unclear what we’re actually going to experience in the movie. We get locked in a bunker at the outset of a zombie apocalypse. Considering that being outside WITH THE ZOMBIES is a much worse scenario, my assumption is that this is a good thing! A movie idea is supposed to pose a problem. Not a solution. I did e-mail the writer, pointing this out, and he said that there are going to be zombies in the bunker that they’re stuck in. Well, that needs to be in the logline then! Also, I’d think that military bunkers could be opened from the inside. So I don’t know how you lock yourself in. That last part is a minor question but it’s the kind of thing that goes through a potential reader’s head when they’re deciding whether to request a script or not. You don’t want that. You don’t want there to be any questions. I hate to use these breakdowns to pimp my logline service but seriously, I could help you get rid of all of these problems. carsonreeves1@gmail.com

Title: The Love, The Bend & The Break

Genre: Thriller

Logline: After an aspiring cyclist’s thoughtful birthday gift sparks his wife’s affair, his curiosities lead him to confront her lover, as he unlocks a fury that even he would never have imagined.

Analysis: I’m beating a dead horse here but, again, we’ve got a logline that’s not giving us enough information. When some of the readers of the site complain that the loglines posted aren’t good enough, you have to understand that more than half of the entries are like these listed above where they don’t give you enough information to even make sense. That’s not to say the script isn’t good. But the logline needs to reflect all of that in a way where we can understand the movie you’re pitching. A thoughtful birthday gift sparks a wife’s affair. What does that mean? Why would a gift do that? It’s such a specific cause and effect that we need to know what the gift is in order for it to make sense to us. From there, the rest of the logline is platitudes and you guys know how much I hate platitudes (“unlocks a fury,” “he would never imagine”). Platitudes are phrases that sound important but ultimately mean nothing because they don’t provide the reader with enough information to understand what’s happening. They are particularly harmful to your logline on the back end of it. You’re supposed to be leaving us with a big exciting climax to your logline that makes us want to read the script! Instead, we get platitudes, which creates the opposite effect.

Title: the secret recipe.

Genre: black comedy

Logline: A frustrated 32 year old man kidnaps the chef from his favorite burger restaurant after repeated failed attempts to get the recipe. He finds out real quick that the chef may not be who he seems to be.

Analysis: For starters, no capitalization on the title or genre. You’re toast right there. Nobody in Hollywood is even going to read your logline after they see that. Show appreciation and care for the language you’re using to tell your story. It’s not only professional but it shows that you care about attention to detail. The first part of this logline creates some sense of a movie. But the logline is destroyed by its second sentence. He finds out the chef’s not who he seems to be. What does that mean? Is he secretly a woman? Is he a vampire? Is he a used car salesman? Is he an alien? Is he a vegetarian determined to destroy the meat industry from the inside? Every one of those options tells a different story. So if you don’t give us that information, we don’t know the story. This is a constant theme with people sending me loglines. They play it too coy. They hide information that they should be giving the reader. One of the best pieces of information I can give everyone writing loglines is PROVIDE MORE INFORMATION THAN YOU THINK YOU HAVE TO. NOT LESS.

Title: Cutie Pie

Genre: Defiled Rom-Com

Logline: When a disturbed female chef falls for a bent cop who’s getting married tomorrow, she cooks up a diabolical plan to win his heart and stop the wedding.

Analysis: I’m going to say this as plainly as I can. THE DIABOLICAL PLAN IS THE MOVIE! Therefore, IT NEEDS TO BE IN THE LOGLINE. One of these days I should livestream myself reading these loglines because all I do, 99% of the time, is either throw up my hands in exasperation or my head falls into my hands in frustration. Cause these problems are fixable yet writers keep making the same mistakes over and over. Why keep the most critical part of your story a secret? It doesn’t make sense to me yet SO MANY WRITERS think it’s the right thing to do.

Title: PHANTASMAGORIA SUCCESSION

Genre: Horror

Logline: After becoming trapped in a logic-defying mansion, a newlywed fights to stop a centuries old supernatural vendetta that will ensure her new family’s global empire and enslave her for eternity.

Analysis: With this one, the issue is more specific. It’s not clear, upon the initial reading, what the “strange attractor” is. A “strange attractor” is the unique thing about your movie that isn’t in any other movie. It’s what sets your movie idea apart and will make people want to read it. I read the logline again and saw, “logic-defying mansion” and decided that that must be the strange attractor. Except here’s the problem: Nobody knows what a logic-defying mansion is. Whatever it is, is the hook of the movie. So it needs to be explained in the logline or else your logline sounds like every other movie where people go to a big house and crazy stuff happens.

Title: Do You Fear What I Fear

Genre: Horror/Comedy

Logline: There will be blood… Elf blood! When a masked killer out for revenge goes on a rampage at the workshop, only Santa’s pissed off, recently-fired daughter Karen can save Christmas.

Analysis: The tagline here is fun. But I need to make something clear to screenwriters everywhere. I’ve read a million and one versions of this logline. For whatever reason, half the screenwriters out there have a Christmas horror script. It *seems* clever but it’s a surprisingly common idea. Also, I just don’t think it works. I get the irony (evil on Christmas). But, at least for me, Christmas is a good time. The Christmas scripts I like celebrate Christmas. — By the way, I’m not saying other people won’t like this. Everybody’s different. But you probably don’t want to send *me* one of these ideas unless it’s honestly the most clever version of this sub-genre ever written.

Title: “LAST BREATH”

Genre: Horror

Logline: When a group of college students discover how to get possessed by inhaling the last breath of people who died, they become hooked on the new thrill, until they go too far and unleash terrifying supernatural forces.

Analysis: I know a few of you liked this one, which is why I wanted to include it here – so you know why I passed. What tripped me up was the logistics of it. I couldn’t understand how they did what they did. Did they just look for people who were dying, hang out nearby, wait until it looked really bad for them, then go kiss them at the last second and hope, during the kiss, it was their last breath? How did they time it? Unless they’re killing these people to create the last breath. In which case that needs to be in the logline. Cause now we’re watching a bunch of serial killers. It just seemed a bit too wonky to work. That’s why I didn’t include it.

Title: Not Alone

Genre: Horror (Found Footage)

Logline: On a cutthroat wilderness survival show, a contestant vanishes. The shocking recovery of her bodycam footage unveils a harrowing encounter with a hermetic clan of inbreds that turns her quest for victory into a desperate fight for survival.

Analysis: I played with the idea of including this one but here’s why I didn’t. If you’re going to revive a dead genre (found footage), you need to bring it back in a way that either reinvents the genre or covers a subject matter that’s never been in that genre before. This feels too familiar. That’s one of the frustrating things about writing scripts. You may have a PRETTY GOOD idea. But oftentimes, “pretty good” is what causes a reader to NOT request a script. “Not Alone” looks like it could be pretty good. But hermit inbreds? I’ve seen that before.

I may do more of these another day. But this gives you an idea of the types of loglines I’m pitched. For the most part, they’re not bad. But they aren’t exciting enough to pull the trigger and feature them. What do you guys think? Did I make a mistake not including any of these?

Don’t worry. Scriptshadow has the best outlining method in the business. Even the Outline Haterz are going to love it.

We are in WEEK 4 of our Writing 2 Scripts in 2024 Challenge. It is probably the most controversial week because this week we’re outlining. And, as we all know, there is a contingent of screenwriters who believe that outlining is Satan reincarnated. I’m not here to argue with those people. All I’m here to say is that the more prepared you are, the better your script tends to end up.

Here are the links to the first three Writing A Script posts if you need to catch up:

Week 1 – Concept

Week 2 – Solidifying Your Concept

Week 3 – Building Your Characters

As far as how much time I need from you this week, at the bare minimum, you need to give me an hour a day. But if you want your outline to have real impact, two hours is preferable. And for those of you youngsters who don’t have jobs yet and have all day to write, put in as much time as you’ve got because when it comes to writing a screenplay, your progress will be proportional to your preparation.

The idea here is we want to create CHECKPOINTS. These are key moments in the script where the scenes are of elevated importance. If you can construct a series of script checkpoints, you’ll always have something to write towards.

The more checkpoints you create, the shorter the distance until the next checkpoint, which makes writing easier. For example, if you have a checkpoint on page 10 and then your next checkpoint isn’t until page 50, that’s where you’re going to run into trouble. The amount of space feels too vast, you don’t know how to fill it up, which leads to the dreaded “writer’s block.”

Remember, writer’s block is rarely about your inability to come up with something to write. It’s more about a lack of planning. The more you plan, the more pieces of your screenplay will be in place, and the easier it will be to connect those dots together.

So here’s the first thing I want you to do. I want you to think of three big set-piece scenes. These are the scenes that are going to sell your screenplay. When you came up with your concept, these are often the first scenes you thought of. For example, if we were writing Barbie, a set piece scene would be the big “I’m Just Ken” musical number. In Heat, it’s that iconic bank robbery scene. In Spider-Man: No Way Home, it’s Dr. Octopus attacking Peter Parker on the highway. In Bridesmaids, it’s the dress try-on scene.

And don’t limit yourself to 3 if you want more. What was so cool about Fincher’s The Killer was every single scene was a set-piece. So he had like eight of them in there. Whatever’s right for your movie, come up with that number of set pieces. And if you really want to do this justice, come up with 20 set-piece ideas and whittle it down to the top 3.

Pro Tip: One of the easiest ways to separate yourself from the competition is to NOT SETTLE. If you settle for the first three ideas that come to you, your script is not going to be as good as if you came up with 20 ideas and picked the best three.

From there, open your outline document and place the scenes at the rough page number where you think they’ll work. Just post “Page 45 – I’m Just Ken musical number.” It doesn’t have to be perfect. Again, you just want to create these checkpoints that you’ll be able to move towards. Even if you only create these three checkpoints, you’ll be in better shape than if you went into your script naked.

The next thing I want you to figure out is your first scene. Your first scene is SO IMPORTANT. I could write 5000 words on the importance of the first scene and it wouldn’t be enough to convey just how important that scene is. So just trust me on that.

If I were you, I would not go with a “setup scene” as your opening scene. This is a scene where you’re setting up a character or setting up your plot. You know the opening scene of Die Hard? Where we meet John McClane on a plane? That’s a setup scene. You CAN do that if you really want. But it’s better to start with a dramatic scene that pulls the reader in.

My favorite example of this is Source Code – the spec script not the movie – A dude lands inside someone’s body on a train and is told he has eight minutes to find a bomb or the train blows up. But a more recent, less intense, example is Tuesday’s script I reviewed – The Getaway. A married couple attempts to have sex in an airplane bathroom and get busted for it. Just make something happen in that opening scene. Don’t bore us.

Okay, now we’re going to get into the technical stuff. Most writers don’t like to do these story beats because it’s, well, technical. Screenwriting is supposed to be free-flowing, fun, artistic. It’s art! Art should never be dictated by technicalities! Yeah, keep telling yourself that.

Screenwriting is inherently mathematical. It’s 110 pages. Those pages are divided into four sections – Act 1, Act 2.1, Act 2.2, Act 3. Essentially, each of those sections are going to be 27 pages long, although that will change depending on the length of your script. But the key to remember is that the end of each section will ALSO work as a checkpoint, since a major moment will happen at the end of each section.

Don’t worry. You’re not going to stick to this like a bible. The nature of writing is that you’re constantly generating new details in your story and those details will generate new story ideas. So, much of this is going to change. But we have to start somewhere.

Which leads us to the inciting incident. This is the thing that happens that INTERRUPTS your hero’s world, usually between pages 10-15. You know that moment in body-switch movies where they first switch bodies? That’s an inciting incident – it’s the disruption of your hero’s everyday existence that now forces them to act. In The Killer, it’s when our main character killer tries to assassinate his target but misses.

After this happens, your hero will be in denial. That’s because just like you and me, movie characters don’t like it when they’re forced to change. So they resist, resist, and resist. But then, at the end of Act 1, which will be your next checkpoint, they accept that they need to solve this problem and head off on their journey (usually around page 25).

The next checkpoint I want you to figure out is your midpoint (around pages 50-60). Now, midpoints are one of the trickier parts of a screenplay because every screenplay is so different that by the time you get to the midpoint, there is no “one-size-fits-all” scene you can write, like the inciting incident. Oppenheimer’s midpoint doesn’t have anything in common with Star Wars’s midpoint. The two movies are trying to do something completely different with their stories.

But something you can keep in mind is that you don’t want the second half of your movie to feel exactly like the first half of your movie. So, for example, if you’re writing a contained thriller where our heroine is being held captive in a basement that she’s trying to escape from – if you just have her try to escape for 90 straight minutes, we’re going to get bored. You need something to happen at the midpoint that changes the story up considerably.

Maybe the most obvious example of this is the movie, Room. The first half of that movie is a woman and her kid being held captive in a room. The midpoint is their big escape. And they succeed. The second half of the movie covers the aftermath as our heroine tries to deal with the trauma of what happened. You can’t do this with most movies. But it’s a great example of how the midpoint should affect the second half of your story.

A more subdued version would be The Equalizer 3. The first half is Robert McCall recuperating in this small Italian town, watching as a local gang makes the locals’ lives a living hell. He doesn’t do anything because, if he does, it will bring attention to himself. But at the midpoint, the gang goes too far, and Robert has had enough. So he starts taking them out one by one.

That’s a good example of a midpoint by the way. The midpoint should always make the second half BETTER, if possible. That’s why Room was not the perfect movie. Its first half was more entertaining than its second half. You always want it to be the opposite.

Once you have your midpoint, your next checkpoint will be the end of your second act (between pages 75 and 90). This is when your hero will “die,” – figuratively of course, but sometimes literally (The Princess Bride). They’ll be at their lowest point. They’ll have tried to solve the problem but failed. There are no other options. The audience should truly feel, in this moment, like there is NO WAY our hero can win. That’s when you know you’ve written a great finale to your second act. In Barbie, this is when Barbie comes back to Barbie Land only to realize that the Kens have taken over.

And the final major checkpoint is your climax. This should be easy because, if you set up a clear goal for your hero at the beginning of your story (John McClane – take down the terrorists and save my wife), then this is the scene where they’ll attempt to do that.

Also, the reason we did that character work last week is so that you can match up your character’s transformation with your climax. For example, if your character’s flaw is that they are selfish, your climax should test that selfishness. It should give them an opportunity to become selfless. If you can pull this transformation moment off, it’s the kind of thing that makes your script feel really intelligent and satisfying.

Okay, those are your major checkpoints. If you get all of those down, you should be in a really good place by the time you write “FADE IN.” However, if you want to go deeper, I prefer that you never go more than 12-15 pages without a checkpoint in your outline (12 if your script is 100 pages, 15 if it’s 120 pages). Even if you just have a cool idea for a scene – that’s all you need for a checkpoint. What we want to do here is close the gap between those big empty holes of space in your script so that you’re never writing in a void. That big void of empty space between checkpoints is when you start freaking out and get writer’s block.

Easy, right?

As you can see, I’m not big on these super-detailed outlines that include things like, “The Circular Resistance Modifier To The Protagonist’s Conflict Moment.” Screenplays are too varied for those specific moments to work in every script. My outlining method keeps things loose enough that you don’t feel controlled by your outline, but it’s tight enough that you have confidence when you start writing your script.

If you have any outlining questions, I’ll be dipping in and out of the comments all weekend. If I have time, I’ll answer what I can. Now start outlining! Cause next week, WE BEGIN WRITING!

The short story sale only took 45 years to happen

Genre: Dystopian/Sci-Fi Adjacent

Premise: 100 teen boys participate in an annual event that forces them to do a death walk until there is only one left.

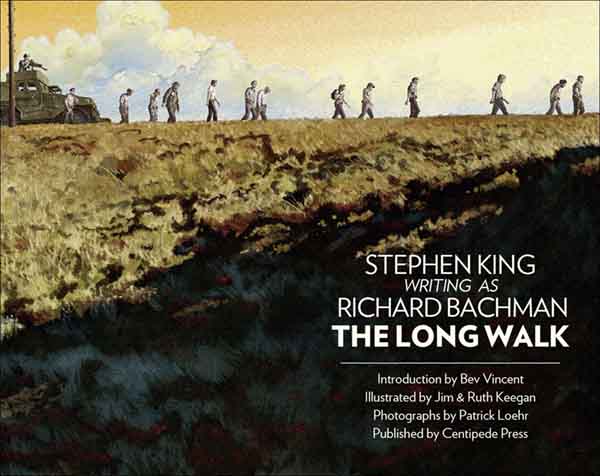

About: Okay, I’m cheating a little. This isn’t technically a short story. But it’s a short story in Stephen King Language, as the man is known for writing 700 page novels. Technically, he would call this a novella. King also wrote this under his fake author doppelgänger, which King invented once he became too popular and figured everyone was buying his books regardless of whether they were good or not. He wanted to challenge himself and see if he still had it as an author, which is why he invented Bachman. The Long Walk, which is 45 years old at this point, was purchased by Lionsgate and will have Hunger Games director Francis Lawrence direct. The film was almost made twice before, once by George A. Romero and once by Frank Darabont.

Writer: Richard Bachman (Stephen King)

Details: (1979) A little under 250 pages, hardcover.

I’ve decided that I’m going to do a Short Story Showdown at some point this year. I’m not sure when but it will probably be June or July. So start coming up with that short story concept because we can’t deny what the current trend is, which is short stories, short stories, short stories.

If I could give you one piece of short story advice, come up with a big idea. Think “high concept” even more so than you would a script. Cause a lot of these short stories are a quarter the size of a screenplay. So you don’t really have time to put your characters through some complex arc. It’s more about a sexy idea that’s going to generate interest in potential moviegoers.

The Long Walk is a great example of this. It’s all about the idea. Let’s see if it offers us anything else.

16 year-old Ray Garraty was chosen to be one of the contestants for The Long Walk, a yearly competition where thousands of boys enter their names in a hat for a chance to compete for the grand prize – all the money you need for the rest of your life. Only 100 names are chosen and Ray is one.

No sooner do we meet Ray than the walk begins! The rules are simple. You have to keep up a pace of 4 miles per hour. If you don’t, you get a warning. You get three warnings total. The fourth time, they shoot you. As in, THEY KILL YOU. The last remaining person to be walking is the winner.

Ray immediately teams up with a guy named Peter McVries. Whereas Ray is more of a wholesome chap, Peter’s got an edge to him. It feels like he’s hiding a few secrets inside that noggin of his. But Peter seems to be as supportive of Ray as he is himself. The two lean on each other a lot as the first contestants “buy their ticket” (Long Walk code for “shot dead”).

The story doesn’t deviate much. It leans into the long grueling competition of trying to keep walking when you’re tired, when you get a Charlie horse, when you get a cramp, when you’re bored, when you get blisters on top of your blisters, when your shoes come apart, when your body wants to give in. Many a contestant tries to game the system – run into the crowd to escape, thinking the guards won’t possibly shoot at them. But it never works. The crowd wants to see them die so they push them back to allow the guards a clear shot.

15 miles turns into 20. 20 to 50. 50 to 100. Days go by. 5 of them in all. Somehow, some way, Ray keeps going. At a certain point, it’s just Peter and Ray. (Spoiler) But then Peter can’t go on. He’s too exhausted. Which means Ray is going to win. When Peter is shot, that’s exactly what we think. It’s over. But did Peter lose count? Is there another player he must outlast? Or is that player death himself? Is Peter even in the game anymore?

A few of you are probably asking, “Why’d you pick this to read, Carson?” Here’s why. The Hollywood system is so obsessed with the word “no,” due to the fact that it keeps them from having to make a decision, that when they finally say “Yes” to something, it’s a really big deal. It’s so hard for any executive to say yes because they know, once they do, that project could go horribly bad and, if it does, they’ll be fired. It’s probably the best view into an exec’s mind you’re going to get. Committing to anything is so daunting that there HAS TO BE SOMETHING SPECIAL about that project for them to say yes to it.

But if I’m being honest with you, the real reason I chose to read this as opposed to a script that sold or a script that made the Black List, is that I knew it was going to be entertaining. King has his storytelling faults. But his stories always place “entertaining the reader” first. So I know I’m going to enjoy the experience of reading The Long Walk.

I’ve read too many scripts to know that most writers don’t prioritize entertainment when writing a story. They’re writing for their own egotistical reasons. Or they’re trying to write something that’s taken seriously. Or they think that readers will stay with them for thirty pages of setup to get to the good stuff.

All King thinks about is the reader. That’s why he’s the most well-known living author. If every writer could take in just a quarter of that desire that King has to entertain people, their scripts and stories would be so much better.

And that’s exactly what happened. I was entertained from the jump.

I mean, do you know how quickly we get to the walk here? Within the first ONE PERCENT of the story! That’s how determined King is to entertain. He knows why you bought this book and he’s going to deliver on that promise. This is especially important with short stories. Not only do you need a high concept premise. But you need to get into that premise faster than when you’re writing a script.

What’s interesting here is that the entertainment comes at us in an unorthodox way. I’m not surprised at all that George Romero was once attached to this because the deaths here aren’t fast and furious. They work more like zombie deaths, where they come slowly. The people involved realize minutes, sometimes hours, ahead of time, that their death is coming. This makes the deaths more realistic, intense, and emotional.

When one kid tells Ray that he’s got a cramp and he’s looking to Ray for help, Ray looks back at him like, “I can’t do anything for you.” And the realization this kid has that nobody can help him is devastating.

That’s the majority of the book. King introduces us to kids along the way, tells us just enough about them to get us to care, then kills them off later on.

Another thing I liked about this story was the rules.

As with any sci-fi (or sci-fi adjacent) story, you have to have rules. Where so many writers screw up is they make their rules too complicated. Or they have too many of them. Or both. Note how simple the rules are here. You have to keep up a 4mph pace. You get three warnings. On the fourth, they shoot you. That’s it! For some reason, writers think that they’re not getting enough out of their story if the rules are simple. So they invent all these complicated rules. But the opposite is true. When the reader easily understands the rules, all they have to do is enjoy the story. They don’t have to constantly rack their brain to remember a + z = q.

Another great lesson you can take from this story is how impossible King makes it feel. With every script you write, you need to make the goal as impossible-feeling as you can AS EARLY as you can.

Ray is not dead tired on mile 97 when there are 3 kids left. He’s dead tired on mile 20 with 97 kids left. That’s how to make the reader wonder, “How in the world is he going to last?” And if the reader is asking that question, I guarantee they’ll keep turning the pages. It’s only when there are no questions left to answer, or the answers to the questions are obvious, that the reader stops reading.

The story does have narrative limitations. It starts to get monotonous since there’s only one thing to do. And I thought that King could’ve done more with the Ray and Peter friendship. If he could’ve made us love this friendship, like he did the kids in Stand By Me, their final walk together would’ve been a lot more emotional. And then, the ending needs work. You could tell King didn’t know how to end this. Luckily, there are options here, starting with strengthening that friendship.

Overall, a solid story that should be a good, but not great, movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A sound strategy for screenwriting is to see what the hot new trend is and go back through your finished scripts to see if you have anything similar. You can do this starting from scratch (writing a brand new script) as well. But trends are finicky. They can last a year. They can last five years. So any sort of head start is preferable. There’s no doubt in my mind that this story got purchased due to the success of Squid Game. And, to be fair, it’s been a while since that show came out. Regardless of that, the quicker you can move on a trend, the better. So if you have that old abandoned spec that is similar to the hot new thing, dust it off, give it a quick rewrite, and get it out there!