Search Results for: 10 tips from

Here are ten screenwriting tips to get you going for 2016!!!

1) Beware of Auto-Piloting – “Auto-piloting” is no different from when you’re going through your morning routine. You’re not thinking because you don’t have to. In screenwriting, auto-piloting leads to cliché choices and lines from other films. The most famous version of this is: “Am I clear!?” “Crystal.” Never auto-pilot. Always think about and challenge your choices.

2) Dead Dialogue – Dead Dialogue is dialogue that doesn’t push the story forward, doesn’t reveal anything about the character, and doesn’t entertain. If your dialogue isn’t doing any of these things, it’s dead. A character talking about a best friend he used to have that has nothing to do with the story? Dead dialogue. Live dialogue is dialogue that does all three of these things.

3) Storytelling is a series of drawing things out – Tell us about something, then wait to reveal it. Hannibal Lecter is boring if you say, “Hannibal Lecter is dangerous” and one second later we meet Hannibal Lecter. He’s way more fascinating if we mention him, then draw out his entrance. Same thing with plot threads. Draw. Them. Out.

4) If it’s easy, it’s boring – If anything is easy for your characters, we’re probably bored watching them.

5) Never write a script that needs directing to complete the vision – If you have to explain that the script is going to be “so much better” because of the cinematography and the music, it means you’re not telling a good story. Tell a good story on the page. Don’t depend on future directing to fix problems. Writers of esoteric indie movies – PLEASE HEED THIS ADVICE.

6) Don’t outpunt your sentence coverage – Don’t walk yourself into sentences you can’t get out of easily. We readers know when you’ve found yourself in a sentence maze and it’s never pretty watching you try to get out. Just rewrite the simplest version of the sentence. If you want to add a bell or a whistle afterwards, that’s fine. But remember that it’s way more important to be clear than to nail a triple-axel super-sentence that doesn’t really make sense in the first place.

7) A character should dictate the story, the story should not dictate the character – There are exceptions to this, but for the most part, the main character should be charging through, creating the story we’re watching. If he’s letting the story happen to him and trying to get out of the way of it, he’s probably not a very interesting character.

8) The more your character talks about something, the less clear it becomes – Some writers think that they can explain something complicated by having their character talk about it for two pages. In most of these scenarios, I find myself more confused than before the character opened his mouth. In general, the less a character speaks about something, the clearer he is. Keep it simple and to the point unless there are story or character reasons to be complex.

9) If your characters are ever talking for the sake of the audience rather than to the other character in the scene, rewrite the scene until the characters are only talking to each other – I understand that exposition is hard. But your job, even when you’re disseminating information, is to make it feel like two people are really talking to each other in real life. Don’t give up on a scene until you get to that point.

10) A story only begins once there’s a problem – The bigger the problem, the bigger the story.

Feel free to add your 2016 screenwriting tips in the comments!

Many people believe that the 70s was the second Golden Era of film, but whether the decade created amazing cinema or not, the reality is there are a lot more forms of entertainment these days, the movie-going demographic has changed, and we’ve been programmed to have shorter attention spans. So no matter how you look at it, the way we tell stories in the medium is different than it used to be. Which makes me nervous about propping up a 70s film to learn screenwriting. With that said, a good story is a good story, and I’m certain that this script would get made today (who would play McMurphy though??). It has that “No. 1 Black List Spot” feel to it. Its secret ingredient is its characters. The film has one of the best collections of characters in history. For those who haven’t seen it, “Nest” is about a convict, McMurphy (Jack Nicholson), who tries to play the system by pretending to be crazy, believing it’ll be a lot easier to do his time in a mental facility than in prison. Once there, he rouses the other patients into action, helping them realize that even if they’re crazy, they can still have fun. But when the floor manager, the deceptively evil Nurse Ratched (one of the best villains ever), sees that she’s losing a hold on the patients because of McMurphy, she finds a horrifying way to solve the problem. One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest won an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay.

1) Starting as late into the story as possible – Yesterday we discussed how you want to start your script AS CLOSE TO the main action as possible. Here’s an example of that in action. In the script for “Cuckoo’s Nest,” we start off with McMurphy at prison, showing him causing trouble. Only then does he get sent off to the ward. In the movie, we don’t show that. We just show McMurphy showing up to the mental ward. It was a good decision. Why do you need to show McMurphy causing trouble at a prison when you can just show him causing trouble as soon as he gets to the mental ward? Additionally, we get to jump right into the story.

2) The “Institution Disruption” Flick – They used to do a lot more of these films (Cuckoo’s Nest, Cool Hand Luke, K-Pax, Shawshank) but you don’t see them as often these days. And I’m not sure why. They’re an excellent set-up for a story. You have an institution (prison, mental ward, school, army) that’s running smoothly, then you bring in a dangerous character who upsets the balance of the group. Conflict is built into the premise, since the establishment will want to regain control over the disrupting individual, which means that a lot of the scenes will write themselves (I’ve found that when you introduce natural conflict into a story, scenes write themselves).

3) How to name a villain – This is well-known device, but I’ll repeat it here anyway. To name your villain, find a negative and/or scary word, then move a few letters around until you get something that sounds similar. “Hatchet” is the operative word here, of course. The writers turned that into Nurse “Ratched.”

4) Ironic villains are typically the best villains – Nurse Ratched is one of the best villains in the history of cinema. But is it because she’s an outward bitch? Because she’s always mean? No. Nurse Ratched is actually quite logical. She’s also calm, and she genuinely wants to help everyone. Her motivation is noble. Had Nurse Ratched had a “Wicked Witch of the West” scowl the second we met her, the character would’ve been infinitely less interesting. This is yet another example of writing villains the OPPOSITE of what you’d expect a villain to be.

5) The dialogue before the storm – One of the things a lot of screenwriting books tell you to do (and I’ve said this too) is to start as late into a scene as possible. For example, if two partners are meeting to talk about their failing business, you’d cut to them in an office with the first line being, “How did we get here?” The thing is, you don’t always want to do that. If you do, your script will start to feel rigid and lifeless. Instead, write in some “dialogue before the storm” to give the illusion of “real” conversation. So when McMurphy is called in to the President’s office to discuss why he’s here at the ward, we don’t start with, “Why don’t you tell me why you’re here, Mr. McMurphy.” We start with McMurphy noticing a fishing photo on the president’s desk and asking him about it. It’s a slightly awkward conversation, since the president wasn’t prepared to talk about the photo, but more importantly, it felt natural. I wouldn’t use this approach in every scene. But you should do it every now and then to create the illusion of reality.

6) Give us one scene that encapsulates the world the protagonist is now in – In the “Institution Disruption” flick, it’s vital that you write a scene that shows the audience exactly what kind of world we’re in. One of the first scenes in “Cuckoo’s Nest” is McMurphy taking part in his first “Group Therapy” session. In it, one of the characters starts yelling at another. Another one quickly breaks down. Another one starts rocking back and forth. Everybody else takes sides, until everyone’s either screaming or yelling or arguing or rocking or making noises. McMurphy looks around at all this chaos. It’s at that moment that we know exactly what kind of world we’re in.

7) Mid-point shift – Remember that the mid-point shift is the moment in your script (roughly the middle of the movie) where something happens that SHIFTS the story in a slightly different direction. Without it, your script will start to feel redundant. The mid-point shift in “Cuckoo’s Nest” happens subtly, when McMurhpy brags to one of the guards that he’s getting out in two months. The guard corrects him. His prison sentence may have had two months left on it. But here at the mental ward, they can keep you… forever. McMurphy’s world is rocked. He had no idea that was the case. Now his “goal” shifts from “act crazy” to “escape.”

8) How to build characters in an ensemble – When you have a bunch of characters in a group, you don’t have time to explore them all. But each of them must still be memorable. To achieve this, give each of them ONE DOMINANT MEMORABLE TRAIT and then keep hitting on that trait throughout the script. One of the patients believes he’s smarter than everyone and looks down on the other patients as a result. Another is the “village idiot” who just smiles all the time. Another just wants everybody to get along. Another has zero self-confidence and is afraid to speak up. When you don’t find that trait, the character will disappear. Christopher Lloyd is actually in “Cuckoo’s Nest,” but you don’t remember him because they didn’t give him a specific trait. You can find this approach in Cuckoo’s Nest, Toy Story, Cool Hand Luke, Shawshank and many other films.

9) The anti-hero method for saving the cat – Anti-heroes shouldn’t save the cat like traditional heroes. Their saving should be a little more complicated. In fact, they might even kick the cat a few times before saving it. If you write them doing something overly nice in a way that’s completely out of character, the story will ring false and the audience will turn on you. The “Save the Cat” moment in Cuckoo’s Nest is when McMurphy tries to befriend the deaf and dumb giant, “Chief.” It’s his support of the character when nobody else supports him, that earns him our sympathy. The amateur writer probably would’ve written this scene with somebody bullying Chief, and McMurphy stepping in to save him. FORCED! Instead, what does McMurphy do? He makes fun of Chief! He does an offensive “How” impression of an Indian. Then does an even more offensive Indian dance to get him to react. It isn’t until later, when he teaches Chief to play basketball, that he starts to help him.

10) Writing a friendship into a story – There’s something about writing a friendship into a story that is so powerful if done right. From McMurhpy and Chief here, to Ratso and Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy, to Red and Andy in Shawshank, to Vasquez and Drake in Aliens. When you do this, for whatever reason, it makes us like the characters twice as much. You guys are welcome to hypothesize on why this is, but all I know is that watching Chief and McMurhpy become friends made me like each of them that much more.

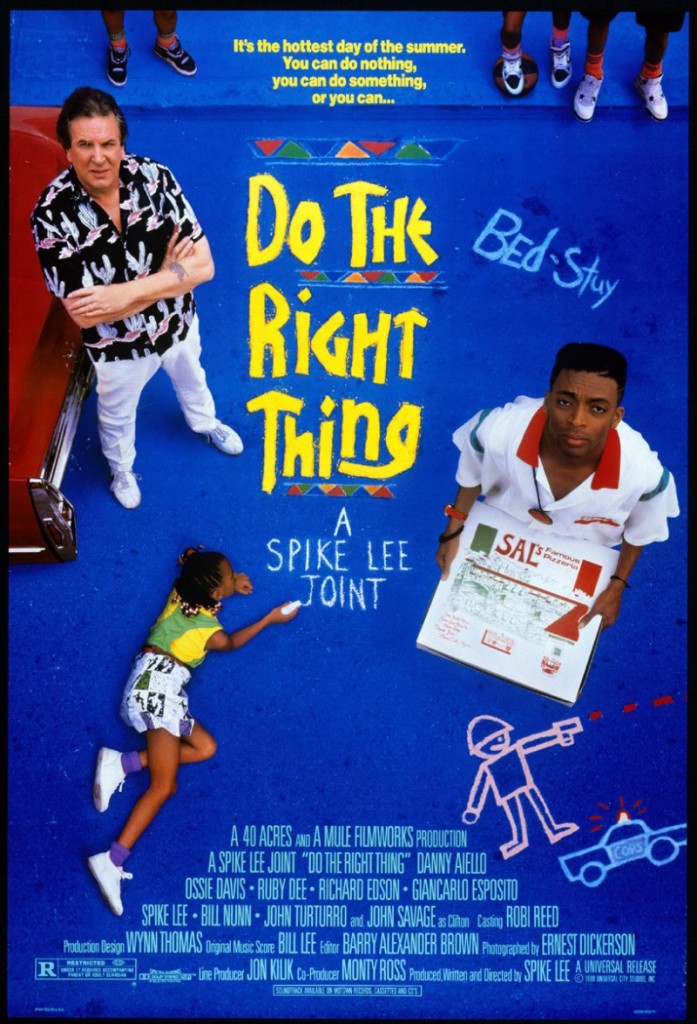

If you search Google for movies with the best dialogue, you get a lot of familiar hits. Writers like Woody Allen, Quentin Tarantino, Richard Linklater, Charlie Kaufman, John Hughes and Aaron Sorkin. Some of these writers thrive on realism (Linklater), others on flash (Tarantino), but all of them have the gift of making you pay attention when one of their characters speaks. It’s an invaluable talent, and therefore quite frustrating if you’re born without it. As I’ve said before, I don’t think mediocre dialogue writers can ever become great dialogue writers. But I think mediocre dialogue writers can become good dialogue writers with a hell of a lot of work. It’s a matter of understanding the basics (come late into a scene, your characters shouldn’t speak “on the nose”) then putting your characters in the best position to say interesting things. That’s what too many writers overlook. They try to write great dialogue out of nothing, when great dialogue typically comes out of setting up the situation beforehand. Today’s script marked the arrival of an incredible new talent, Spike Lee. One thing everybody agreed on was that Lee hit out of the park with the dialogue in this script. I couldn’t agree more. Try watching this movie and turning away. Every time someone speaks, you want to hear what they have to say. Why? What magic potion is Lee using? No magic. Just tried-and-true dialogue-writing methods. In fact, even the naturalism in Lee’s dialogue is born out of an easy-to-learn lesson. I do want to highlight a couple of non-dialogue tips here too, but dialogue will be the focus. Let’s begin!

1) The power of character differences – Sometimes all you have to do to write great dialogue is put two different people in a scene and have them talk to each other. Use differences in age, differences in race, differences in political views, differences in class. That’s what gives Do the Right Thing so much of its great dialogue. The different races always see the world differently, which is what leads to all these conflict-heavy entertaining conversations.

2) Choose stories that hide your writing weaknesses just like you choose clothes that hide your body weaknesses – This is self-explanatory yet a lot of writers make this mistake. If you’re a flashy dialogue writer, write a movie that’s heavy on dialogue. If you’re not, avoid scripts like Do the Right Thing like the plague. Good writing can be as simple as staying away from the things you’re bad at.

3) Another way to develop character – My big takeaway from this script is that character development isn’t always about a character changing. It’s about a writer revealing more about that character over time to create the illusion of change. The drunk old man looks like a loser at first. But the more we learn about him, the more we like him. He even saves a kid from a speeding car later. So he doesn’t change as a person. But he changes in our eyes because we know more about him now than we did at first.

4) Add fuel to the conflict fire whenever possible – Remember, most great dialogue results from conflict. So you should look for any way to stoke that conflict. This script already has a ton of conflict because of all the racism. But Lee adds the WEATHER to make it even worse. In Do the Right Thing, it’s the hottest day of the year. People have less patience in hot weather. They’re more easily agitated. A simple argument can escalate quickly. Which is exactly what happens.

5) In One-Day stories, the weather can become a character – I realized that if your script takes place over one day, the weather can become a major character in your story. Here, it’s the heat. But in another movie, it can be the coldest day of the year. Or the rainiest. Or the day of a huge blizzard. When you have a movie that takes place over this short a period of time, pay attention to the weather, as the right weather choice can have a huge impact on the story.

6) People on the same side don’t always agree – Even characters on the same side should disagree about things. Don’t assume that just because Sal and his son work together at Sal’s Pizza that they’ll have the same views about everything that’s happening. What I liked about Lee’s script is that Sal was respectful of others, whereas his son was racist. Sal wanted to help people. His son wanted them to help themselves. This lead to conversations between the two that were way more interesting (“Maybe we should get rid of this place, Dad.”) than if these two thought the same way. Remember, not every scene can be two people with hatred towards one another yelling for five minutes. Conflict has to live within your groups, not just outside of them.

7) Easiest way to write dialogue is to write what you know – Lee grew up with all these characters in his neighborhood. That’s why they all feel so real. Whatever people you grew up with, particularly the eccentric and most memorable, make sure you’re writing those people into your scripts. They’ll write the dialogue for you. Never underestimate the power of this simple tip (this is the “naturalism” tip I was referring to in the intro).

8) Theme allows for “pointless” dialogue – Here’s the thing with dialogue. Its main purpose is to push the story forward. The thing is, real life dialogue, the kind that’s free-flowing and crazy and fun to write, doesn’t push anything forward. It’s just people talking. Which means each time you write dialogue, you’re trying to write an oxymoron. The reason Lee’s dialogue is so good in “Thing” is because a lot of it isn’t pushing the story forward. It’s dialogue of the free-flowing crazy variety. So how is he able to get away with it? Easy. Lee has a strong theme in his film – racial tension in the city. When you write with a strong theme and keep the dialogue focused on that theme, you can get away with “rambling” dialogue, because the dialogue still feels relevant. What does four guys yelling at a man for stepping on his shoe have to do with the plot? Nothing. But the man who owns the shoe is black. And the man who stepped on the shoe is white. Therefore, this “pointless” dialogue-heavy scene feels relevant because this whole movie is about racial tension.

9) Variety in characters leads to better dialogue – One of the best things about Lee’s script is how different all the characters are. We have a weird radio carrying guy (Radio Raheem), we have an old drunk man, a man with a lisp, the mentally retarded guy, the African Pride Radio announcer, the troublemaking crew, the old “complainer” guys across the street. The more variety you have in your characters, the more interesting their conversations are going to be. Period.

10) As always, look for unique ways to evolve old phrases – This is where you really see the pros stand out. They take old well-known phrases and turn them into something we haven’t heard before. Sal doesn’t say, “I should kick your ass” to Mookie. He says, “If you were just a little bit taller, I’d kick you in the ass for what you’re thinking.”

BONUS TIP) Evolve phrases by utilizing character specifics – Notice how the above phrase is focused on Mookie’s height: “If you were just a little bit taller.” Lee uses this specific trait of Mookie’s to inspire Sal’s change of the line. It’s easy for you to do the same. For example, if you’re writing a rom-com where a woman is asking our main character (who’s a lawyer) how he knows some important piece of information, his reply might be, “I’d tell you but I’d have to kill you,” But everyone uses that line. So look at your options. What’s specific about our character? He’s a lawyer, right? So maybe the response is, “I’d tell you but I’d have to bill you.” That’s admittedly lame but you get the idea!

There was a time long ago when you couldn’t turn on your TV and not find The Warriors playing. It must’ve been the first movie ever syndicated or something because no matter what house you showed up at, what street you passed through, what party you attended, there was The Warriors. My memory of the film was formulated on these viewings. And I must admit, I haven’t seen it since. All I remember is that the movie had that indescribable something that made it unforgettable. Unforgettable good? Unforgettable bad? Unforgettably cheesy? It’s hard to say. Which is why today’s Ten Tips will be the first in the site’s history where I expect to note both good and bad screenwriting tips. I mean, there’s a roller-skating gang-leader. The movie was written and directed by Walter Hill (he worked off a screenplay by David Shaber, who adapted the script from Sol Yurick’s novel). Hill wrote and/or directed some good movies in his day like The Getaway, Hard Times and 48 Hours. Unfortunately, he had a really bad experience in 2000 with the movie Supernova. The studio wrestled the movie away from him, famously recutting it with numerous directors (even Francis Ford Coppola took a stab at it). The movie was famously awful and Hill said it was because it deviated heavily from his original darker vision (however, he claims to have never seen the film). Since then, Hill has worked mainly in the background of Hollywood, mostly in television.

1) ALWAYS WORKS – The wrongly accused protag! We will always love and root for the wrongly accused protagonist! Here, the Warriors have been wrongly accused of killing Cyrus, the beloved gang leader. It’s for this reason that everyone’s trying to take them out. Combined with The Warriors’ underdog status as a gang, it’s no wonder we root for them from the first page.

2) Don’t throw a female character in the script just to have a female character in the script – This tends to happen in macho male-driven films. The writer knows he needs a female lead but doesn’t want one, so he tosses one in there without any thought as to how or why she’s involved. This happens in The Warriors. The prostitute who hung with The Orphans just decides to join the Warriors for NO REASON. Come on now. As a writer, it’s your job to FIGURE OUT A WAY to get your female characters into the story naturally.

3) When the stakes are sky-high, simple scenes become awesome scenes – When the stakes are high (in this case, The Warriors can run into death at any corner), creating a simple objective with an obstacle in front of it can lead to a great scene. There’s a moment where the Warriors have to get to the train. But the Skinheads are blocking their way. We watch as the tension builds. They have to decide if they’re going to go or not. They finally make a run for it. A chase ensues. We’re on the edge of our seats wondering if they’ll be able to catch the train in time. It’s a simple scene, but one of the best in the movie. And it’s so simple!

4) If your characters are trying to outrun something, make sure you explain why they can’t just stay where they are – I had a problem with this here. Since there was no urgency in The Warriors (they didn’t need to be anywhere by a set time), I didn’t understand why they couldn’t just stay put and leave the next night when the city was less volatile. There are vague references to dangerous cops and gangs finding them. But it seemed to be a lot more dangerous trying to get home rather than staying put. This is why a ticking time bomb always works. It explains why your characters can’t stay put.

5) Is backstory bad? – Walter Hill has an interesting take on backstory. This is what he says: “I very purposely — more and more so every time I do a script — give characters no back story. The way you find out about these characters is by watching what they do, the way they react to stress, the way they react to situations and confrontations. In that way, character is revealed through drama rather than being explained through dialogue.”

6) Counterpoint – Backstory ain’t so bad – I see Hill’s point. Exploring characters through their actions is one of the best ways to develop them. More importantly, it keeps the story in the present, where movies work best. But these days, actors, producers and readers need more from their characters. They need to feel like those characters have lived a life. Backstory does that. The trick is to keep the backstory relevant and never give more than you have to.

7) Never underestimate the power of a simple plot – Hill, who was given a draft of The Warriors before writing his own draft, loved the “extreme narrative simplicity and stripped down quality of the script.” Looking back at it, I think that’s why the movie had such an impact on children, in addition to adults. A stripped down plot means every audience member, no matter what age, will be able to understand what’s going on. If you then want to up the adult appeal, add complexity through themes or social commentary or characters, whatever floats your boat.

8) Your main characters shouldn’t be wimps – One thing I realized when re-watching The Warriors was: THESE GUYS ARE WIMPS! They’re always running away. They’re only fighting when they’re cornered. If you have a macho hero-driven movie, make your hero a hero! Have him go after the prize instead of running or hiding. Obviously, in chase movies, your hero will be on the run. But when the opportunity arises and it makes sense, have them stand up for themselves. There wasn’t enough of that here.

9) Beware the Split-Up Paradox – In movies with group protagonists, there’s inevitably a time when the group splits up. My suggestion to you? Think twice before doing this. Watching The Warriors, I was all in for the first 40 minutes. Then, I noticed my concentration wandering. I wasn’t as into it. That’s when I realized the gang had split into three (or maybe four?) mini-groups. I wasn’t sure where any of them were or what they were trying to do. If you’re going to split up your characters, KNOW that this could be a problem and take counter-measures. Keep each mini-storyline focused (give them goals, makes sure we know where they are). And just like the overall story, try to give urgency to these tangents. If you don’t, our minds will start to wander.

10) Write your villain to steal the show – I read SO MANY boring villains with no personality. It’s no wonder I forget them the instant I put down the script. Honestly, I can count the number of memorable villains I’ve read in screenplays this year on one hand! To prevent this, write your villain to steal the show. Make SURE he’s memorable. Luther, despite having something like 5 minutes in the film, is a villain I still remember to this day. He’s small (unlike a typical villain). He’s a weasel. He’s a bully. He’s got a temper. But the big thing is, he just LOVES to have fun. He leads the charge when it’s time to get into trouble and he loves it. “Warrr-eee-orrrrs, come out to play-ye-yeeee.” If your villain ain’t stealing the show, you probably have a weak villain.

It’s Thanksgiving so what better movie to extract 10 screenwriting tips from than “Planes, Trains and Automobiles!” Okay so there weren’t a lot of movies to choose from (it was either this or Pauly Shore’s “Son In Law”). Still, any time I get to break down a John Hughes script, I’m a happy man. The thing about Hughes is that he came from a marketing background. So he understood the fact that people have short attention spans. They don’t like to be confused. And they like to understand what they’re getting into. Which is why he kept all of his films easy to understand and, therefore, easy to market. The road trip film is a cinema staple. But its biggest strength (the fact that it’s so simple) is also it’s biggest weakness (it’s hard to make unique). Still, at its core, these kinds of films were built for screenwriters. The road trip angle gives the script a clear goal and forward momentum, and the contrasting personalities gives the script natural conflict. All you have to do is come up with a few interesting characters and scenarios we haven’t seen before. From what I hear, Hughes shot a TON of footage to ensure just that (twice the industry average actually) and there’s rumored to be a 3 hour cut of Planes, Trains and Automobiles somewhere in the Paramount film vault (this cut is 90 minutes). I live about four blocks from Paramount so maybe I’ll head over there before the big turkey day and see if I can find it.

1) If you don’t have a ticking time bomb in your road trip movie, you probably don’t have a road trip movie – If your characters are heading to a destination in your script, they should need to get there by a certain time. And it should constantly look like they’re not going to make it. Here, of course, our characters are trying to get home by Thanksgiving.

2) Look for the visual jokes in these movies – Writers get caught up in the humorous back and forth between their characters when they write road trip movies. It’s all about the dialogue between the leads. But remember, the visual jokes tend to be the ones that hit the hardest. There’s no better laugh in “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” than when Steve Martin finishes his shower only to see that John Candy’s used all the towels and the only dry one left is a tiny washcloth. Never underestimate the power of visual jokes that are just WAITING to be found.

3) The idiot shouldn’t think he’s an idiot – With Will Ferrell and Zach Galifianakis films becoming so popular, self-aware comedy has become huge. But remember it’s not the only way. Some of the funniest characters are the characters who have no idea that they’re grating, that they’re smothering, that they’re annoying, that they’re rude. The idiot shouldn’t always think he’s an idiot. He should think he’s the smart charming guy. That’s what makes John Candy’s Del Griffith so memorable. He has no idea how annoying he is.

4) If characters are stuck together, they better really be stuck together – What drives me craaaaazy in these scripts is when writers keep their characters together for no logical reason at all. If there’s a moment where characters would logically split up, you either have to come up with a believable reason why they don’t or you should split them up (and reunite them later somehow). That’s what happens here. They finish the bus ride and, during lunch, Steve Martin just says, hey, there’s no reason for us to be together anymore. And they go their separate ways.

5) The two things a buddy road-trip movie MUST have – When you write these movies, there are two things you must adhere to. Assuming, of course, you already have two characters with friction between them, the first is that things need to KEEP GETTING WORSE for these characters. At first it’s the plane being diverted to a different airport. But later it’s getting robbed. Later still it’s blowing up a car. And the second is that the IRRITANT character needs to KEEP GETTING MORE IRRITATING. At first John Candy’s just leaning on your shoulder on the plane. But later he’s sleeping on you with his hands between your legs. And later still, he almost kills you by slipping your car between two semis.

6) Give your comedy more leeway by avoiding caricatures – I learned this one from critic Leonard Maltin. He noted that the reason this movie’s occasional slapstick scene (them nearly crashing into two semis) didn’t disrupt the film’s more serious tone, is because neither main character was a caricature. They both had real goals, real lives, real backstory, real emotions, real frustrations. They were genuine. And because we believed them as people, we bought into the sillier parts of their adventure. Had they been hamming it up for the screen and thinly drawn and “caricatures” of real people, the movie would’ve quickly devolved into empty nonsense during those sillier moments.

7) Caricatures work great for one-scene characters though – One place to go wild with caricatures, however, is with one-scene characters. These guys don’t need to be deep, so you can have fun with them. Owen the redneck Truck Driver (“My wife’s so strong her baby came out sideways and she didn’t even scream”) is a great example.

8) If your story’s fast, write fast – This is by no means a hard and fast rule. Every writer should develop a method that works for them. But there’s something to be said for writing fast when your story’s time frame is fast. This story takes place over three days and John Hughes wrote it in three days. There’s something about the energy you write with when you’re writing fast that matches the energy of a fast story. Keep in mind, though, that Hughes routinely does 20 drafts AFTER his first draft.

9) Write that scene an actor is going to love – Steve Martin, who was really hot at the time of this movie, said he signed on because of two scenes. The scene where he curses out the car rental attendant with 18 “fucks” in one minute, and the “seat-adjustment” scene in the car. You have to be thinking of your actors when you write because actors are the number one element for getting your script purchased. What scenes in YOUR script will an actor be dying to play?

10) Write the dramatic version of your comedy first – Again, I don’t think every comedy should be written this way, but I know Judd Apatow does it a lot (and tells all his writing disciples to do as well). To make sure the emotional beats are there, the reality is there, and the characters are authentic, write the DRAMATIC version of your comedy first. Then, as you rewrite, start looking for and adding jokes. Although I have zero evidence to indicate this is how “Planes, Trains and Automobiles” was written, it sure feels like the kind of movie that could’ve been written that way.

![planes-trains-and-automobiles-poster[1]](https://scriptshadow.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/planes-trains-and-automobiles-poster1.jpg)