Search Results for: 10 tips from

I’ve been feeling bad since I wrote the article last week about the six types of scripts least likely to get you noticed. I got a lot of e-mails from people who were writing those scripts, and boy were they unhappy. I was most affected by those who had written sports movies. I love sports and I love a good sports movie. So my heart goes out to those struggling to get their sports script through a system that just isn’t receptive to the genre. I still believe that the only realistic shot you have of getting your sports spec picked up is to option an interesting true story or write about a compelling sports figure. With the unending number of sports games that have been played throughout time and the number of sports figures that have lived and died on this earth, there are still so many interesting stories that have never been told. With that said, if you’re going to write a sports script, you may as well learn from the best. And Hoosiers is as good as it gets. I’m going to find out what made this script work, as well as pass you a few tips about sports scripts in general. There’s one thing I can’t explain, though. How is it that the writer of this great movie, Angelo Pizzo, has only written TWO PRODUCED MOVIES since???

1) Character over sport! – Easily, one of the biggest mistakes writers make when writing sports movies is focusing on the sport instead of the characters. Remember, audiences don’t care about that final goal, that final shot, or that final touchdown, unless they care about the person making it. You almost want to approach your sports script as a character piece that has sports elements, as opposed to the other way around. Formulate a compelling controversial memorable main character, then feed the sports stuff in there. You see this in Rocky, The Natural, Hoosiers, Bull Durham, and all the best sports movies throughout time. A great main character first!!!

2) Try to give each player on the team small character flaws they must overcome – In a sports movie, it’s essential that each kid have that one clearly defined character flaw that’s holding them back from being the best player they can be. Take the short player in Hoosiers. He doesn’t believe in himself. He thinks of himself as just a practice player. He eventually learns to believe in himself and ends up helping the team win a key game. Every player has to have their own little storyline!

3) You need to give the coach a COACHING FLAW – Same deal. Every sports movie needs that coach who has a flaw that’s preventing him from being the best coach he can be. Gene Hackman’s character refuses to listen to his players. He’s only going to do it HIS WAY. In the last timeout of the championship game, then, we see him overcome this flaw when he allows the kids to run their play instead of his.

4) Every sports movie needs a TEAM PROBLEM – This is some play issue the team can’t seem to get over. Here, it’s the concept of “team.” Don’t dribble the ball up the court and shoot. You HAVE to pass the ball four times before anyone can shoot. This concept is a constant battle throughout the movie, with certain players refusing to go along with it. As a result, it was satisfying when they bought into coach’s game plan and started winning because of it.

5) Write around a sport – If you’re a big sports fan but don’t want to write yet another cliché sports movie about a team or player who overcomes the odds and wins the championship, consider writing about the people surrounding the sport. The reason this works is because it introduces us to a new exciting world we’re unfamiliar with. Cameron Crowe did this famously with sports agent Jerry Maguire. Zallian and Sorkin did it with Moneyball. And more recently, Scott Rothman and Rijav Joseph did it with Draft Day, the number one Black List script, which focused on an NFL general manager during draft day.

6) MIDPOINT SHIFT ALERT – Remember, a midpoint shift is a severe event in the middle of the story that shifts the second half of the movie so it feels different from the first. In most cases, that moment makes things worse for your hero. But here, it actually makes things better. The mid-point shift of Hoosiers is when Jimmy (the star player) announces that he wants to rejoin the team. With Jimmy now on the squad, it’s no longer about becoming a decent team, it’s about winning. It’s about having a legitimate shot at being great!

7) Make the romantic interest a source of conflict – I like when the romantic interest is also one of the main sources of conflict for the main character. You end up killing two birds with one stone. Here, Myra, the vice-principle and main love interest, is the only person in Indiana who hates basketball. Talk about a tough girl to chase if you’re the new basketball coach!

8) Write about the coach – As I watched Hoosiers for the billionth time, I realized something. There are no other truly good basketball movies in sports history (unless you count Air Bud and Love & Basketball). It doesn’t seem to be a sport that lends itself to cinema. I wanted to know how Hoosiers overcame that and not only became the best basketball movie of all time, but the best sports movie of all time. I came to the conclusion that it’s because the main character wasn’t one of the players. It was the coach. This falls in line with my above tip: “Write around the sport.” Concentrating on the coach allows you to tackle problems from the person with the most power over the game. The decisions a coach makes (who to play, who to sit, who to favor, who to discipline, how to train, how to strategize) in addition to the exterior pressures he faces (the way the town wants him to play, the way the manager wants him to play, the way the star player wants to play) typically make him one of the most interesting people to watch. That was definitely the case here.

9) Each game needs to be its own little movie – With each game in your script, you want to create your own little movie with its own specific problem, something the characters will all learn from and, whether they realize it or not, get better from. The first game in Hoosiers, for example, is about the players not listening to the coach. That’s the problem. So what does Coach do? He sits the most egregious player of the bunch, even when the team needs another player on the floor! He’d rather play FOUR players than have someone not listen to him. The problem is solved by the end of the game. The players now realize that it’s the coach’s way or the highway. And highways go on forever in Indiana.

10) Create a compelling goal that works concurrently with the main storyline – If the only question you have for us in your sports movie is, “Will they win the championship?” we’ll get bored. You need other storylines working concurrently with the main one, another goal our main character must achieve. Here, it’s “Getting Jimmy,” the player who many consider to be the best in the state, but who has no interest in playing.

BONUS TIP – Tie your elements together – Where real writing comes into play is when writers learn to tie the elements that make screenplays work together. So in this case, Angelo Pizzo has written in some great conflict between our main character, Coach Dale, and the romantic interest, Myra. He’s also created this great subplot (that I just mentioned) where Coach Dale needs to convince Jimmy to join the team. Individually, both these situations work well, but it’s tying them together that makes them truly powerful. Myra doesn’t like basketball. She believes it’s way more important for Jimmy’s future that he focus on his studies, which is why she doesn’t want him on the team. Therefore, one of the biggest elements of conflict in the movie, Myra, is also the obstacle Coach Dale must get past in order to land Jimmy. That’s great writing!

Warning: Spoilers below. Please watch movie before reading this article.

It seems almost silly that I’ve run a screenwriting blog for five years and never once looked at The Usual Suspects. It’s kind of like writing a football blog and never mentioning Jerry Rice. The Usual Suspects was written in 1994 by a then unknown Christopher McQuarrie when his director buddy, Bryan Singer, called and said he’d been given money to make a movie and needed a script (a problem we all wish we had, no doubt). McQuarrie cooked up this strange little time-bouncing noir mystery about a group of usual suspects who meet during a line-up and quickly find themselves hunted by the most ruthless killer in the world, Keyser Soze. A couple years later, McQuarrie found himself holding an Oscar. This dream ended up in a nightmare, however, as McQaurrie stumbled into a decade long stint of development hell, writing numerous projects that never made it to the big screen (or did with other writers) and watched as his stock plummeted with each failure. It got so bad he considered leaving the film industry. It wasn’t until 2007, when Tom Cruise rescued him to write his film, Valkyrie, that McQuarrie’s career was reborn. He recently wrote and directed the modest hit, “Jack Reacher,” for Cruise again, and has since written a draft or two of the always-scary-to-imagine Top Gun 2. In probably one of the most fascinating things I’ve ever heard about a successful film, McQuarrie recently admitted that he and Singer realized they had completely different conceptions about the plot. “I pulled Bryan aside the night before press began and I said, ‘We need to get our stories straight because people are starting to ask what happened and what didn’t. And we got into the biggest argument we’ve ever had in our lives. One of us believed that the story was all lies, peppered with little bits of the truth. And the other one believed it was all true, peppered with tiny, little lies. … We each thought we were making a movie that was completely different from what the other one thought.”

1) Ignoring the rules only works if you get to make all your movies on an island – McQuarrie didn’t really know how to write when he wrote The Usual Suspects. He ended up breaking a ton of rules due to his ignorance (time-jumping, voice over, too many characters). The result was a hit movie and an Oscar. You’d think, then, that the lesson would be, “Ignore the rules.” Well, sorta. Once McQuarrie moved from the indie world to Hollywood, none of his projects went anywhere. The reason for this is that McQuarrie didn’t really know how to write Hollywood movies. He didn’t understand structure and character and goals and stakes and conflict and all the things that make mainstream movies go. So he kept turning in drafts that nobody liked. He kept doing it HIS way. The lesson here is that if you can pull off a Wes Anderson or Quentin Tarantino or Woody Allen and write and make movies off on your own little island, you don’t need to pay attention to what Hollywood says. But if you plan to work in the system, you better study every screenwriting book out there and understand how this business likes their stories told.

2) Explore concepts that allow you to create characters audiences have never seen before – The coolest thing I took away from The Usual Suspects is that when we finally meet Kobayashi, Keyser Soze’s right-hand man, it turns out he’s white and British. At first, this doesn’t really make sense. But in retrospect, you realize this was because Verbal (Kevin Spacey) was making up the story as he went along. He spotted the name “Kobayashi” on the bottom of his coffee cup, and simply turned him into a British guy in the story. I’m not sure a white British man with a Japanese name would’ve ever made it into a script otherwise. This got me wondering why more writers don’t explore ideas that allow them to introduce unexpected characters into their screenplays. It seems like an easy way to turn stereotypes on their head.

3) Don’t drop your reader into a time-blender in the first 5 pages – The Usual Suspects has an overly confusing opening that bounces all over the place. We start one day ago on a boat, then cut to present day for a split second, then jump back 6 weeks ago. The problem with this is, we don’t know your characters yet. We don’t know what story you’re telling. We’re not yet used to your writing style. We know nothing and you’ve already dropped us into a blender. So the first two times I saw The Usual Suspects, I had no clue what the actual timeline was. Even watching it this time around, I was a little confused. Only jump around in time early if there’s NO OTHER WAY for your story to work. And if you do, please pay a tremendous amount of attention to orienting your reader. But yeah, I’d just keep that opening easy to follow.

4) Extend a mystery with a delay – This is a neat little way to give a cool mystery extra life so you can milk it for a few extra scenes. When the boat blows up at the beginning of the film, there’s a survivor, a man in critical condition suffering from 60% burns to his body. This man knows what happened, which means he can solve our mystery! So the police come to find out what he knows but…oh no! He speaks Hungarian. Now the police have to go out there and find a Hungarian translator! The mystery continues. And we get a couple more scenes wondering what this intriguing character knows.

5) CONFLICT ALERT – As I always tell you guys, the best drama is packed with conflict. And that’s clearly the case with The Usual Suspects. Lots of conflict all over. But I don’t think anyone can deny that the best scenes in The Usual Suspects take place between Kujan (Chazz Palminteri) and Verbal (Kevin Spacey). And the reason for this is their scenes are based on one of the oldest conflict setups in the book: A character who wants something (Kujan), and a character who doesn’t want to give it to him (Spacey). You do that, you have conflict, and you will always have a scene (or in this case, an entire movie full of scenes).

6) A CLEAR MYSTERY can soften the confusion of a dense pot – If you have a dense multi-layered plot like The Usual Suspects, offset it with one big CLEAR mystery the audience can easily follow. Not everyone is able to follow what’s happening in The Usual Suspects. There’s a strange set of time jumps, lots of characters, and an ever-changing story, but you won’t find anyone who doesn’t want to finish the movie in order to solve the big mystery: WHO IS KEYSER SOZE???

7) Characters should speak in their own unique voice – One of my favorite lines in The Usual Suspects is when Kobayashi (Keyser Soze’s Number 2) warns Keaton (Gabriel Byrne) that if he kills him, his wife “will find herself the victim of a most gruesome violation.” I’ve heard so many cliche bad guys dish out over-the-top threats like, “I’ll fuck your wife and make your family watch.” It’s refreshing to hear an uptight, upstanding, proper gentleman threaten in exactly the manner and tone you’d expect a man like him to threaten in. It’s a reminder that you’d like all your characters to speak in a way only they would speak. This is one of the reasons The Usual Suspects is so popular. It had a ton of unique characters who all spoke THEIR OWN way.

8) Always think like an actor when writing characters – Fenster (Benicio Del Toro) was nothing like the character McQuarrie originally wrote. Benicio turned him into an overly-primped excessively-styled unintelligible mutterer, and the result was one of the more memorable movie characters of the decade. It’s a great lesson for writers. Actors are looking to create the most complex interesting characters possible. By simply thinking like one, you can do this for them, and your script will be populated with much more interesting characters as a result. I guarantee it.

9) You must be smarter than the reader in the subject matter you’re writing about – Readers are smart. They have the internet. They know a lot of things. So if you’re going to write a script, make sure you know that subject matter better than the reader. This may seem obvious, but I read tons of embarrassing screenplays where I know more about cop procedure than the writer who’s writing a cop procedural. That’s embarrassing. Cause I don’t know much about cop procedure. The result of this realization is that I don’t believe in the writer anymore, which means I lose confidence in him, which means I lose confidence in the script, which means the script is dead to me. McQuarrie worked at a detective agency for four years before he wrote this. He knew how the hierarchy of this world worked and it shows. If you don’t have that knowledge going into your script, research the subject matter until you do. I promise it will pay off.

10) When writing a group of characters, make sure to create dynamics WITHIN the group – There is no group of people in this world where everyone knows and likes each other equally. They all have side friendships, people they like and dislike, histories, guys they trust and don’t trust. Here, Fenster and McManus (Stephen Baldwin) are good friends. Verbal (Spacey) engages in a friendship with Keaton (Gabriel Byrne). Hockney (Pollack) kind of knows everyone. By digging in and understanding the dynamics within your group, the group will feel more complex, and by association, genuine. It’ll also help you know your individual characters better.

Now a lot of you are probably asking, “Carson, why the hell did you pick Cast Away for a script breakdown?” I’ll tell you. Because it’s different. Because it took chances. Because it’s something that shouldn’t have worked. And I love breaking down scripts that shouldn’t work. I love exploring the deviations and figuring out why they succeeded (when so often else, they fail). The film itself famously teamed up Robert Zemeckis and Tom Hanks and took a YEAR BREAK in the middle of production so that Hanks could lose weight and look like a real castaway for the second half of the film. That story overshadowed screenwriter William Broyles Jr.’s own escapades to get the script right. The Apollo 13 and Planet of the Apes scribe deliberately stranded himself on a beach in the Sea of Cortez for a week to force himself to search for food, water, and shelter. For today’s tips, I’ll be reading an earlier draft of the script in order to see some of the changes they made.

BUY WILSON HERE! – Wilson

1) If your protagonist cares about something enough, so will we – The success of Wilson The Volleyball defies just about all rationale. Many people actually cried when he was swept out to sea at the end of the film. Although rumors persist that I was one of those people, I steadfastly deny my involvement in any Wilson-related crying. The question is, why did this happen? Well, if your protagonist really really cares about something, whether it be a family member, a goldfish, or a volleyball, we will too. And you can use that tool to create moments like this one, where you rip that something away from the hero to provoke an emotional response from the audience.

2) The Set-Up World needs to be exciting – The “Set-Up World” is that 10-15 pages BEFORE the inciting incident. The inciting incident, of course, is when something happens to throw your character’s world into disarray (in Cast Away, this is when the plane crashes, obviously). Here’s the problem I see in a lot of scripts. Writers believe that because they’re just “setting things up” and the exciting inciting incident is right around the corner, that The Set-Up World can be boring. They can show their protagonist doing boring things and it’ll all be okay because the fun is coming soon. NO. It’s very important that during The Set-Up World, you set up your character in the most interesting way possible. So here, we show Chuck (Tom Hanks) running all over the world, desperately trying to ensure that Fed-Ex packages arrive on time. He’s yelling at people, busting his ass to get all the packages on the trucks. Things are HAPPENING. You can intersperse a few slower scenes in this section, but be careful. Too many and we’ll get bored before your inciting incident even arrives.

3) Know what you need to set up in the Set-Up World. Set up those things and nothing more – Make a list of the ESSENTIAL THINGS you need to set up about your main character. Come up with those scenes and don’t include ANYTHING MORE. This will keep your setup streamlined. In the early draft of Cast Away I read, there was all this extraneous stuff about the FEDEX headquarters and Chuck’s family that JUST WASN’T NECESSARY. Broyles Jr. and Zemeckis figured out they needed to set up Chuck’s job, his relationship with Kelly, and that was it. So those other scenes were excised.

4) If your protagonist’s life is boring and therefore uninteresting to document, get to your inciting incident sooner. – If your protagonist is someone who doesn’t have an interesting life to set up, such as The Dude in The Big Lebowski, try to get to your inciting incident even sooner. We establish The Dude in a robe at the grocery store. Then in the very next scene, when he gets home, two thugs attack him and piss on his rug, which is the inciting incident that starts the story. Exciting characters can have longer Set-Up Worlds. But do NOT give us 6-7 scenes of a stoner being stoned before the inciting incident arrives. We’ll give up on the script before it happens.

5) IRONY ALERT – Remember, always add irony to your script if possible. Double points if it’s a part of your premise! Chuck is the man who’s always on a tight schedule, who never has a second to spare. All of a sudden he’s on an island with all the time in the world.

6) Recognize when you have a good character and expand his role – Surprisingly enough, Wilson was barely in the draft of the script I read. But someone recognized how powerful he could be and so majorly expanded his role. If you have a show-stopping (or interesting or memorable) character, make sure to give him as much time as you can in your story. An example of a writer missing the boat on this was George Lucas in Episode 1. He had a badass villain in Darth Maul, but didn’t recognize it, didn’t expand his role, and therefore missed an opportunity to do one of the only things right in that script.

7) MID-POINT SHIFT ALERT – Remember, a good mid-point shift SHIFTS the second half of the movie in a slightly different direction so it’s not the same as the first. We have a pretty clean mid-point shift in Cast Away. We cut to 3 years later, with Chuck no longer being the green timid survivalist, but an aged vet of the island who’s figured out how to survive.

8) If you are going to jump forward in time, use an event to motivate it – Staying on that topic, I always see writers insert huge time-jumps into their scripts that come out of nowhere. We’ll be sitting with a family watching TV, and then the next line I read is… “8 months later.” If you’re going to make a big time jump in your screenplay, try to create a weighted moment to initiate it. Cast Away does this with Chuck’s tooth, which has been killing him for weeks it hurts so badly. He finally has no choice but to take it out. He does so with a rock, and the pain causes him to pass out, which leads perfectly into a FADE IN and a “3 years later.”

9) We need to be constantly reminded of the motivation if we’re to care about your hero succeeding – In this draft, Chuck did not have a picture of Kelly (his girlfriend) that he kept looking at to keep him going. I was shocked by the effect it had. In the movie, I so wanted him to get off the island. In this draft, I definitely didn’t care as much. The more I thought about it, the more I realized how big of an effect that picture of Kelly had. Because I was reminded of her, I constantly wanted Chuck to get back to her. Getting off the island to survive is selfish. Getting off the island to get back to Kelly is selfless.

10) The 10 Draft Rule – Every script should go through at least 10 drafts. The Sixth Sense had 20+ drafts. Good Will Hunting had over 50. And by ‘draft,’ I don’t mean going through a script and casually rewriting scenes you don’t like. An official ‘draft’ is where you read through your script and assess all problems (what is and isn’t working) in order to come up with solutions to apply to those problems. I read way too many scripts that feel like early drafts, such as this Cast Away draft which includes ten early pages of family scenes that are totally unnecessary to the story. That unfocused stuff drains its way out of the screenplay after ten drafts.

BONUS TIP – Good Chuck, Bad Chuck, Fuck Chuck – Here’s proof of the above. In this draft of the script, Chuck starts going crazy and is therefore split into two personalities, Good Chuck and Bad Chuck. Clearly, this was a method designed by Broyles Jr. so that Chuck could logically speak out loud and we could learn what was going on in his head. It was also a very cliché EARLY DRAFT choice. By going through many more drafts, he eventually realized that Wilson The Volleyball could take on the roll of someone for Chuck to talk to. I read too many scripts where writers don’t get past Good Chuck, Bad Chuck. And the script suffers for it.

These are 10 tips from Cast Away. To get 500 more screenwriting tips from movies as varied as “When Harry Met Sally,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

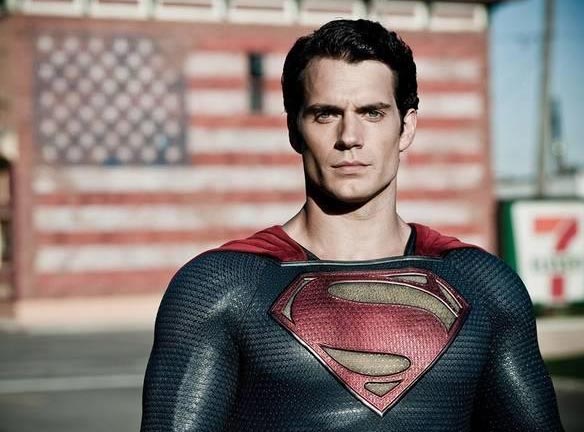

So last week I took some kryptonite-laced shots at the man of steel for being a “reluctant” protagonist, an issue I contend can destroy a screenplay. What’s a reluctant protagonist? It’s a hero who doesn’t want to take on the problem. I contend that we don’t like our heroes wimpy. We don’t like them sitting back and doing nothing. It’s the exact opposite of what the word “hero” means. However, there’s no such thing as a screenwriting rule that works across the board. There are times where the reluctant protagonist works, The Godfather being one of those examples. This gave me an idea to kill two birds with one stone. I’m not the foremost authority on The Godfather, and therefore wanted a reason to read it. And I knew that Michael Corleone, the main character, is a reluctant protagonist, which would allow me to see why the character works here when in so many other scripts, it doesn’t. I’ve also always been drawn to how slow stories work. Only the best writers know how to keep you turning the pages during a slow burn. So those are the main things I went into this script looking for. Let’s see if I found my answers, or any good tips for that matter. (you can have 500 MORE TIPS just like these by buying my e-book here)

1) Counter your hero’s reluctance with positive qualities – I think the biggest issue with reluctant heroes is when you couple them with a downbeat or depressed disposition. The combination of those two things always makes characters droll and boring. Look no further than Superman in Man of Steel for that. Instead, look for traits that CONTRAST that negative quality. One of the best traits you can use to offset this is charisma. Michael Corleone has it. William Wallace (a reluctant hero from Braveheart) had it. A double dose of negativity can quickly make your hero moody, depressed, and a downer. Steer clear of that with a positive trait (if not charisma then something else!).

2) If you have a reluctant protagonist, the earlier you can break out of being reluctant, the better – In actuality, most screenplays have reluctant protagonists at the start of the story. This is the period where they’d rather stay in the safety of their everyday lives than take on the pressures of this new adventure that’s presented itself. So we almost always see reluctant protagonists become willing and active participants at the beginning of the second act. For stories where this doesn’t happen, note that the longer you keep your hero reluctant, the more frustrated with him we’re going to get. Because we came to your movie to see your hero DO SHIT, not RESIST DOING SHIT. Michael Corleone starts being active pretty early, when he must protect his father after the assassination attempt.

3) There’s a difference between an reluctant active protagonist and an reluctant inactive protagonist – I think the problem I had with Man of Steel was that Clark was not only reluctant to do anything, he DIDN’T do anything. A reluctant character works much better if, even though he doesn’t want to get involved, HE DOES. Michael Corleone doesn’t want to be doing the things he’s doing, but he does them anyway. Another famous reluctant character, Mad Max, didn’t want to be there helping any of those people, but he did because it furthered his own agenda. Ditto with William Wallace. He didn’t want war, but he realized it needed to happen to free his country. So write a reluctant protagonist, just make sure he’s out there still being active.

4) If you have a character you need us to like who does bad things, introduce them doing good things – Vito Corleone (The Godfather) does a lot of bad shit. He’s hurt a lot of people. He’s killed a lot of people. But the power of writing is that you can make the audience like ANYONE. Don’t believe me? Have you seen Silence Of The Lambs? Yes, writers have made cannibalistic serial killers likable. One of the simplest ways to do this is to introduce your “bad” character doing something good. Vito Corleone is introduced helping a man whose daughter was beaten and nearly raped by two men who got away with it. He orders those men to be taken care of. How can you dislike a guy who’s taking down rapists?

5) Outline big party scenes – Big party/event/wedding scenes (anything with a lot of people) are some of the hardest to write. Writers often bounce around from character to character without a plan, which results in a messy directionless sequence. When you’re writing a big scene, like the famous wedding scene that opens The Godfather, make sure to plot out beforehand every character and what that character is doing. Preferably, you’ll have characters that need something during the sequence (a goal!), as that tends to make things more focused and interesting. Here we’d map out all the people coming to the Godfather with their requests. We’d map out Miachel showing up with his new girlfriend – what they’re going to talk about and why. We’d map out a scene to show that Carlo, who’s marrying the Don’s daughter, is sketchy. We’d map out Michael’s brother Sonny, who cheats on his wife with one of the bridesmaids. Map all of this out ahead of time and make sure each set of characters is doing something IMPORTANT. That’ll keep you from lingering on irrelevant stuff, which is where these big sequences go to die. Have a plan and you’ll do just fine at your next wedding.

6) A reluctant protagonist in a drama has a much better chance of working than a reluctant protagonist in an action film – Know what genre you’re writing when considering the reluctant protagonist. In an action movie, when your audience wants a lot of action, it’s going to be pretty silly if your main character is avoiding it all. In a slower drama, however, where plot and action aren’t as important, you have more freedom to play with a reluctant lead. I’d still be wary of it, but you do have more freedom there.

7) The best setups and payoffs establish high stakes during the setup – Remember, a payoff doesn’t really resonate unless you establish high stakes when it’s set up. That’s what makes the famous “horse head in the bed” scene so powerful. The day before, Jack Woltz, our unlucky movie producer, shows Hagen (Don’s lawyer) his horse stable and gushes about how much he loves horses, especially one in particular, a 600,000 dollar horse which he’ll put out to stud, leading to endless riches. Guess which head ends up under his covers? This scene doesn’t work the same way if Woltz casually passes a race track and barely points out a horse that he likes. We build the stakes up high by having him LOVE this horse.

8) Always look for an indirect way to handle backstory/exposition – Remember, one of the most boring ways to convey backstory or exposition is to lay it out in a very straightforward manner via dialogue. Instead, try to find an angle that conveys the information in a nontraditional way. They did this quite cleverly in The Godfather. Michael tells Kay (his girlfriend who knows nothing about his family’s lifestyle) about Luca Brazi, the muscle for his father. His story is about how Luca was sent over to take care of these men who attacked his father. The backstory for this character he gets into is very graphic and violent. But Coppola added an angle. Michael is smiling while he’s telling the story, so Kay isn’t sure if he’s telling the truth. Gone is the on-the-nose boring rundown we’re USED TO in these situations, replaced by a, “is he or isn’t he telling the truth” angle that makes the same information kind of fun. It’s a slight change, but it’s these slight changes that separate you from the next guy, who’s doing it the obvious way.

9) Conflict, suspense and mystery are your friends when writing a slow story – When you don’t have urgency (as is the case with The Godfather), you need to use other tools to keep your audience interested, or else they get impatient. You do this with these three tools: suspense, conflict, and mystery (and tension – though it can be argued that tension is conflict). Consistent use of these should keep even the slowest stories interesting. We see conflict, for example, in all of the requests of Vito Corleone, who makes his guests work for it. We see tension in his relationship with Michael, who doesn’t want to be involved in the family business. We have suspense in what’s going to happen with Johnny, the movie star who desperately needs a part from a producer who won’t give it to him, in Michael needing to save his father at the hospital when he knows the bad guys are coming, and leading up to the dinner where Michael plans to kill the police chief and Sollozzo. There aren’t a lot of mysteries in The Godfather, but that’s an option for you to use as well. If you’re writing a slow screenplay and you’re not using these three tools frequently, your script is probably boring.

10) How committed are you? – The more I read, the more I find that the deepest most emotionally affecting stories are based on books and real life. Why? Because the writer has tons of backstory and character knowledge to draw from. When a screenplay is written from nothing, the writer often doesn’t fill in the details that happened before the story. As a result, the characters never project any depth (why would they? They never existed before they were placed on the page). I’ve constantly been looking for a solution to this. How does one manage the same depth of a book adaptation without writing a book? Is it possible? Or should a screenwriter actually write a book before his screenplay? It sounds nuts but I GUARANTEE you, if you did that, your screenplay would be a hundred times deeper than if you didn’t. And aren’t we all looking for an advantage over the next guy? Reading the opening of The Godfather (based on the book by the same name), with this huge wedding, with Vito Corleone listening to requests for help, with Sonny cheating on his wife, with Vito’s daughter desperately trying to keep a man she barely has, with Michael introducing his new girlfriend to everyone, to Luca Brazi, to movie stars pleading for a break, a spec writer just wouldn’t know or care about 75% of these characters. They’d know their hero, they’d know the second most important guy in the scene, and then maybe one other character (the lead girl). Everybody else they’d know their first name, what they’re wearing, and that’d be it. And that’s exactly why all spec scripts feel so thin. To measure up to this expected level, try to write as much backstory as you possibly can on every character in order to give them as rich and as detailed of a history as you can. Then and only then, will they project the kind of depth and presence characters in adapted scripts like The Godfather project.

There’s a reason I’m busting out The Dark Knight for this week’s Ten Tips. This weekend I experienced a super-human catastrophe in Man of Steel. And I want to look at an actual well-made superhero film to see how to do it right. What’s interesting here is that two of the major players are the same in both projects (Christopher Nolan and David Goyer). The big flashy addition is Zack Snyder, which tells me that his paws may have been the ones that dirtied up the Man of Steel waters. With that said, I’m not going to pretend like The Dark Knight is some tour de force in screenwriting. I’ve battled many a time with this screenplay and feel that it has just as many weaknesses as it does strengths. With that said, it’s a far superior screenplay to Man of Steel, particularly in the area of character. So let’s see what we can find when we compare the two behemoths. I suspect some some nifty tips!

1) Give us a main character who’s active – It’s one of the simplest and often-stated screenwriting rules there is, and yet us screenwriters constantly forget it, finding ourselves 60 pages into our screenplays and wondering why they’re so boring. One only needs to watch Man of Steel to see how an inactive main character can destroy a movie. It makes them (the main character) bland, which forces the story/plot to work overtime to overcome this issue. That’s likely why we had so much overplotting in Man of Steel. The writers sensed something was wrong but couldn’t figure out what, so they just kept ADDING MORE PLOT. The simplicity of having an active main character is that they forge forward, carving out the story on their terms. Look at Bruce Wayne. The guy wants to make a difference so he creates Batman to do so. He WANTS to fight crime and clean up the streets, so he’s always out there actively pursuing that. Superman in Man of Steel is the opposite.

2) Beware the reluctant protagonist – Building on that, Man of Steel made me take a hard look at the reluctant protagonist. By “reluctant,” I mean a character who’s reluctant to engage in the central conflict of the film. That’s Clark Kent. He’s reluctant to get involved in the world’s problems. A big reason this doesn’t work is because by being “reluctant,” you’re basing the entirety of your hero on a negative trait – avoidance – which pretty much goes against everything that’s fun about movies (our hero ENGAGING in the adventure). There are movies where it works (Michael Corleone in The Godfather) but it usually doesn’t, especially in action movies. The word “reluctant protagonist” now scares me. It should probably scare you too.

3) Just tell us what’s happening dammit – I’ve read a few amateur screenplays recently where the writer tries to do way too much with their action description. They write stuff like, “Sweat glistens off Joe’s knuckles as he wrestles the gun out of his pocket.” There are times where you want to add a little flair to your writing, but for the most part, just tell us what’s happening. Here’s how Jonathan and Christopher Nolan write an early scene before the bank robbery in The Dark Knight: “A man on the corner, back to us, holding a CLOWN MASK. An SUV pulls up. The man gets in, puts on his mask. Inside the car – two other men wearing CLOWN MASKS.” These are two of the top writers in the business and every word in that description is something a third grader would understand.

4) “A&P” (An Active main character with Personality) – The character type who’s typically the most fun to watch is ACTIVE (making his own decisions and pushing the story forward himself) with PERSONALITY (is charming or funny or clever or smart or a combination of all these things). Look no further than one of the most beloved characters of all time, Indiana Jones, to see how that combination works. Or Iron Man. Or Sherlock Holmes. While I wouldn’t say Bruce Wayne is going to open at The Laugh Factory anytime soon, he does have a personality, likes to have fun with his money, and has a sense of humor. Combined with his desire to fight crime (being active), he’s got the coveted A&P. Superman in Man of Steel has neither the A or the P, which is why he’s so forgettable. As a rule, try to have the A and the P for your protag. If you can’t, give him the A or the P. If you can’t give him either, I guarantee you you have a boring protag.

5) Backstory is the enemy – Remember that superhero origin stories are by definition required to show us the backstory that led to our hero becoming who he is. In the real world of spec screenwriting, backstory is the enemy. Unless there’s some really unique or traumatic or shocking thing that happened in our character’s past, don’t show us. And if you do, show us only the bare minimum of it. It can even be boiled down to a quick expositional sentence if you do it right. Batman Begins handled its backstory a lot better than Man of Steel, but in both cases, the main plot (taking down the Scarecrow and Zod respectively) had to be pushed to the second half of the script, something that will never be accepted in the spec arena.

6) Invisible Backstory is your friend – You may not tell us a single thing about your main character’s past, yet you – the WRITER – should know everything that happened to your hero since the day he was born. This knowledge leads to SPECIFICITY OF CHARACTER, a character who is unique because of the extensive “real” life he’s lived in your imagination. The less you know about your hero, the less specificity you’ll be able to infuse him with, which leads to genericness. This is one of the quickest ways I can differentiate the boys from the men in screenwriting.

7) Conflict is your weapon against exposition – One of the earlier scenes in The Dark Knight has Bruce talking to Alfred about needing improvements to the Bat Suit as well as getting info on the new District Attorney (who’s dating Rachel). It’s a straight forward exposition scene and, for that reason, one of the more forgettable of the film. Contrast this with when Bruce meets Harvey Dent (the District Attorney) out for dinner. Harvey’s with the love of Bruce’s life, Rachel, and Bruce has brought along a hot ballerina. There’s a lot of exposition in this scene, mostly in regards to Harvey trying to save the city, but the scene is fun because of the conflict: Wayne sizing up Harvey and the jealousy between Bruce and Rachel. Conflcit is your weapon against exposition. Use it whenever the evil EXPO rears its head (Nolan forgot this simple rule in Inception, which is why so many of his early scenes are boring. They’re pure exposition with zero conflict).

8) Brains over brawn – I think one of the reasons Batman is more popular than Superman is because he can’t just fly away. He can’t just use his heat vision to burn a hole through a guy. He’s gotta use his brains. Granted, he’s got a lot of money and that money has created a lot of gadgets, but Batman’s way more dependent on his wits than his powers. I bring this up because I read so many scripts where the writer gets his hero out of a battle with a gun or a roundhouse kick or a superpower. The thing is, it’s always more rewarding when the hero uses his wits (his INTELLIGENCE) to get out of that situation. So always look to your hero’s mind to solve his problems, first. Only use physical force as a last resort.

9) Have your bad guy earn his keep – Whenever I re-read The Dark Knight, I’m always studying the villain, since the Joker is one of the most famous villains of all time. He’s lasted decades, whereas most villains last the two hours that make up the film (Die Hard With a Vengeance anyone?). Upon reading The Dark Knight, I realized that for truly timeless villains, you gotta like them a little bit. And I think one of the reasons we like watching The Joker is because the guy earned his keep. He wasn’t handed anything. He had to rob a bank and infliterate and intimidate the biggest baddest nastiest dudes in town. As crazy as it sounds, we kind of respect him for that, and it makes us sorta like him. So make your bad guy earn his keep. We’ll respect him (and actually like him) more.

10) Rational vs. Irrational Villains – Something I noticed while comparing The Dark Knight to Man of Steel, is that they have two polar opposite villains. General Zod is rational and calculated and has strong reasoning for doing what he’s doing. The Joker, on the other hand, is irrational and unpredictable and confusing. No doubt The Joker is the much scarier of the two. Through this, I learned the value of bad guys who are a bit unpredictable, a bit out of control. When you think about it, those are the scariest people in life because they don’t have that “rational” button you can push. I was never scared of General Zod cause the guy was just so darn rational.

These are 10 tips from the movies “The Dark Knight” and “Man of Steel.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!