Search Results for: 10 tips from

E.T. is a strange film to talk about from a screenwriting perspective. Throughout the first half of the film, not a whole lot “happens.” And what I mean by that is, once E.T. and Elliot meet and Elliot brings him into the house, the next 40 or so minutes have the two simply hanging out and avoiding mom. I’m not sure I’d advise a screenwriter to try that approach today. The reader would be itching to get out of the house and get the story “moving.” It begs the question, is E.T. a product of its time? Could the same film be made today? The answer is probably “no.” I think we’re too impatient and too cynical to have E.T. in this world. Then again, you could make the argument that E.T. is lightning in a bottle. There was nothing like it, there will be nothing like it, and it was just a one-off, something that inexplicably worked where any movie attempting something similar would’ve failed. Today’s theme is FAMILY FILM tips, a genre that pretty much died when Spielberg grew up. Is there another writer/filmmaker in the shadows ready to replace him? If so, I hope he reads today’s 10 tips!

1) SYMPATHY FOR THE ANGEL – You want a scene that creates sympathy for your main characters so that we’ll root for them (preferably the very scene you introduce them with). This is doubly important in a family film. I mean, how does a family film work if we’re not rooting for the main characters??? The writer, Melissa Mathison, knows this, and creates a great introduction scene for E.T. where we see him left on earth. It is the terrifying feeling of watching his ship head home without him that immediately endears us to the alien. We’re afraid for him. We want him to find a way back.

2) Don’t be afraid to change the direction of your story if it’s not working – Your first take on an idea isn’t always the best. As you write, you may discover there’s a much more interesting story to tell. The stubborn writer ignores this truth and continues on writing because it’s too much work to change. The smart writer follows the better idea, even if it means a drastic rewrite. Spielberg started E.T. as a horror film where a group of aliens terrorize a family in a remote cabin. But the script wasn’t working (it’s a mess – I’ve read it). His favorite part was a key friendship that emerges between one of the aliens and one of the children. That idea, a friendship between an alien and a boy, became the focus of his next draft.

3) Find the high concept (the hook) in your un-commercial idea – Spielberg admits that E.T. is autobiographical, outside of the alien of course. I realized that this is what sets Spielberg apart from everyone else. When he comes up with an autobiographical idea, he doesn’t film a direct translation of it. He finds a hook to get people in the door (in this case, an alien) then tells the emotional story about his life through that hook.

4) If you play with a new toy too much, you get bored – One of the great things about E.T. is the deliberate development of the alien. Sure, he could’ve started talking on page 15, but he has to learn about this world and interact with these people and make mistakes before he finds out how to speak. I find that most writers get their shiny new toys (an alien, a robot, a monster) and burn them out right away. By page 30, there’s nothing left to discover. Take your time developing your new toy. Make sure he evolves over the course of the story, not within the first 20 pages.

5) Bring your own family issues and problems into your stories – Did your parents’ divorce fuck you up? Is your mom a raging alcoholic? Are you unable to meet the lofty standards your father expects of you? Whatever shitty family circumstances have shaped you as a person, use your scripts to explore them. Family dynamics always feel authentic when the writer is drawing from his/her own experiences. You see that with Spielberg here in E.T., who was notably torn up by his parents’ divorce and his father leaving the family. That undercurrent hits the family hard and plays a big role in the story.

6) URGENCY ALERT – Remember, you always want to infuse some urgency into your story. Here, it’s the government looking for E.T. We keep cutting back to them getting closer in their search, so we know it’s only a matter of time before they find out E.T. is at Elliot’s. This script is a lot less interesting if we ONLY focus on Elliot and E.T. hanging out and becoming friends. We need to feel like their time’s running out. Urgency!

7) Wish-fulfillment – I think a big thing when you’re writing family films is wish-fulfillment. You want to integrate some sort of wish-come-true (to be a superhero, to be invisible, to have an alien as your best friend) and then make your hero (usually a child) need to keep that secret. When executed well, this approach rarely fails.

8) Family movies can be serious – I think too many writers become goofy with their family screenplays. It’s all farting and burping and poop jokes and over-the-top humor. What I loved about E.T. was that it took itself just seriously enough that you forgot you were watching a movie. It dealt with real family issues and real problems (loneliness). These days, it’s all flash and no depth (see the alien family film “Aliens in the Attic” as an example of what NOT to do).

9) Family Fun and Games – Blake Snyder was the inventor of the phrase “fun and games” and it refers to the section at the beginning of your second act, after your concept has been established. So here, it’s when Elliot moves E.T. into the house. At this point, you just want to have fun with your idea. So with E.T., Elliot has him meet the family, E.T. learns about television, he gets drunk, he goes out on Halloween. I don’t think the Fun and Games section is right for every genre (I didn’t see it in “Prisoners” for example) but the one genre it is an absolute requirement for is family films. You can also dedicate more TIME to the Fun and Games section in a family film (it’s traditionally supposed to be under 15 pages – but here it lasts over 30).

10) Alternate Goal Character – E.T. is one of the rare movies where neither the main character (Elliot) or the villain (there is no villain in E.T.) have the goal that’s driving the story. In this case, it’s actually E.T. who has the goal (he’s trying to get home). It’s a nice reminder that SOMEONE in the story has to have a goal that’s driving the story forward or else your story’s going nowhere. I mean think about it. What if E.T. didn’t want to go home? We wouldn’t have a movie!

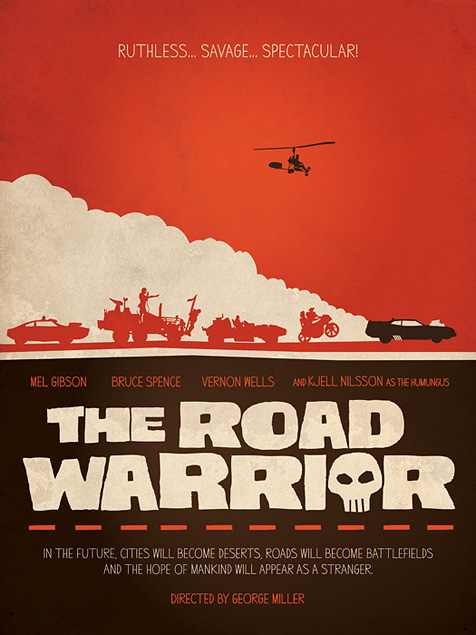

Man, I’m going off-book for every post this week. I said I was going to do ten tips for The Karate Kid or Rain Man, but instead, I’m going with another 80s movie, The Road Warrior! Now The Road Warrior may seem like an unlikely choice for a plate of screenwriting lessons. The script focuses mainly on action, which doesn’t translate very well on the page. But look closer and you’ll find that how the script tackles action is the secret to its success. Today’s studio films are so jam packed with action, they’ve lost track of why they’re adding it in the first place. Maybe to fill up their trailers. Maybe because they’re afraid the audience will get bored. I don’t know. But The Road Warrior comes in at a lean 95 minutes, and only includes action sequence when they’re necessary (true, the smaller budget probably contributed to this, but that may be a lesson in itself – don’t spend money if you don’t have to). What sticks with you when you watch The Road Warrior are its amazing set pieces (read: car chases), and particularly the climactic chase. These may not be as flashy as the stuff you see today, but they’re definitely more brutal and real. That’s because there were no special effects. Everything you saw was real. The problem with these digitally-aided chases today is that they all carry a sheen of fakeness. And “fake” feels safe – the exact opposite of how you want your audience to feel in the theater. But I’m getting off track here. Let’s reach back to one of the greatest action movies ever and see if we can’t learn something from it.

1) Never underestimate a simple story – I see so many writers writing themselves into corners because they’re trying to do too much with their story. Look at the plot of The Road Warrior. The good guys must find a way to escape the bad guys with their fuel in tact. The great thing about a simple plot is that the audience is never confused. Everybody always knows what’s going on. These days in movies like Transformers 2 or Pirates of the Caribbean 4, that’s rarely the case.

2) Universal Motivation – Movies work well when there’s universal motivation. This means every character is motivated by the same thing. In this case, it’s fuel. Every character wants it. No character wants to give it away. This provides ample opportunities for conflict, since all of your characters are fighting over the same thing.

3) If your hero doesn’t say a whole lot, make sure he does a whole lot – A character who doesn’t speak much must speak with his actions. Max isn’t a talker, but he’s very active. If he’s not outrunning the road pirates, he’s stopping to inspect curious objects (the gyro-copter), forming his plan to get into the fuel yard, heading out to get the fuel truck. He’s always DOING something. If you have a character who doesn’t speak and doesn’t do, you have a boring character.

4) Script Exercise: Pretend that sound isn’t working on set today – Pretend you’re a writer on set and the director’s just informed you that the sound equipment broke. Hence, you need to come up with a version of the scene that doesn’t contain dialogue. As a guideline, watch the scene in The Road Warrior where Max befriends the Ferrel Kid. There’s no dialogue in it but it’s very powerful. Max takes out an old music box he found on the road and starts playing it. The kid is intrigued. Max plays a little more before tossing it to him. The kid spins the crank, the music comes out, and he gets excited. It’s a simple scene, but it establishes a solid friendship between the two. The Road Warrior has a few really nice moments like these.

5) Establish the danger in your world – If we don’t feel the danger, we won’t be afraid. And you need your audience to feel afraid of the bad guys. Early on, we watch a band of the road pirates mercilessly kill a man and rape his wife. Admittedly, this would be a hard scene to show today. But it really established how dangerous this world was. If you do this right, it will pay dividends throughout the rest of the movie. When the bad guys are chasing Max in the truck, for example, we know if they catch him they’re not simply going to put a bullet in his head. There will be torture, pain, horrible things done to him that we can’t even begin to imagine. Which is why we don’t want him to get caught!

6) Urgency in the form of an ultimatum – One of the easiest ways to create urgency is through an ultimatum. The road pirates come up to the oil yard and broadcast an announcement that the good guys have 24 hours to leave the yard or else they will be slaughtered. Urgency is one of your best friends as a storyteller (as evidenced by yesterday’s article), and this is a really easy way to instigate it.

7) Make characters memorable with their actions, wardrobe, disposition, possessions – Too many writers try to make characters memorable with their words. Instead, look for ways to make them memorable with their actions and outfits and overall disposition. Helicopter Guy wears goggles and has a quirky flying machine. The Ferrel Kid speaks in grunts and has a bladed boomerang. Max eats dog food to survive. It’s these extracurricular things that the audience typically remembers, not what your characters say.

8) You want your hero going into the climax at his worst – The worse your hero is prepared for the climax, the better. Max is nearly dead when he takes control of that tanker. He’s got one leg, one eye, and one arm (think about that – he has only ONE ARM to drive this tanker!).

9) You want your bad guys going into the climax at their best – It shouldn’t be a fair fight. The bad guys have 30 cars and hundreds of weapons to Max’s 1 car and handful of weapons.

10) Find irony in your set pieces – Set pieces are supposed to be big and action-packed and crazy. So writers look for the biggest most action-packed craziest way to do them. By taking this approach, however, they often miss out on the more nuanced moments that make a set piece memorable. Many times it’s the TINIEST thing that can be the stand out moment in a set-piece. For example, in the ending of The Road Warrior, a final shotgun shell rolls out onto the hood of the truck. It’s out there dangling on that dashboard and getting that final bullet turns out to be the only thing we care about for two minutes. This amongst an insane car chase with over 30 cars!

As great as this movie is, there’s still one thing I haven’t been able to figure out about it. Max is a really selfish hero. He doesn’t care about anyone but himself. He’s not very talkative. He’s a dick to everyone. I mean there’s a moment where he’s about to save somebody but before he does he says, “I’ll only do this if you give me gas.” But we still love this guy. Why? Is it as simple as that he has a dog? That he connects with the little kid? Is it that the bad guys are so much worse? Max today would probably be rewritten to be more “likable.” And it would’ve ruined the character. So my question to you is, why do we like Max? I feel like if we can figure that out, we can shed some light on just what “likable” means.

Scriptshadow is not dead! Between Labor Day Weekend and preparing for my upcoming vacation (next week), time has been scarce. Speaking of, what are you guys going to do while I’m gone? Maybe you should write a script in a single week. You can then post the results (or a summary of the experience) on the site. I’ll call it the Scriptshadow Is Gone Write A Screenplay In A Week Contest. If you need inspiration, go watch this video. As for today, we’re taking a time machine back to the 80s. Seeing as Michael Douglas cheating on Catherine Zeta-Jones with Matt Damon has led to their divorce, it’s only natural that we take a look at one of his earlier marriage screw-ups, when he cheated on his wife with Glenn Close. The reason I chose this script was because thrillers remain one of the three go-to genres to sell a spec screenplay. They’re lean, high on intensity, take you through a range of emotions, and are relatively inexpensive to make. If I were starting my writing career today with the knowledge I have now, I would write either a comedy, an action script, or a thriller. That’s where the money is. While it didn’t win any Oscars, Fatal Attraction was nominated for six Academy Awards, including best picture, best actress, and best adapted screenplay.

1) Thriller titles must be visceral – With straight thrillers, the title should illicit a strong visceral reaction. It must imply the extreme emotional gamut it will run the audience through. The original title for this movie was “Divergent.” I think we can agree that doesn’t have nearly the same punch as “Fatal Attraction.”

2) Start where you need to start – With thrillers, there’s a temptation to start the script with a very “thriller-like” scene, or a “teaser.” Our femme fatale eerily cutting herself in the darkness of her apartment while listening to opera music, for example. But it’s more important to start the script where it needs to in order to set up the story. In order to convey that our main character would seek out an affair, we need to establish that he’s bored with the married family life. So the first scene, then, is about Dan (Michael Douglas) muscling through an evening with the family.

3) Just make sure the scene’s interesting – If you aren’t going to wow us with a teaser (such as the one I mentioned above), remember that you still have to hook the reader right away. For that reason, you want your first scene to convey a sense of purpose, a sense of activity, a sense of forward momentum. Fatal Attraction does not begin with a family sitting at home eating pizza watching a movie, for example. It begins with mom and dad getting ready for a dressy work event. This gives everyone something to do. We are propelling forward towards something. As a reader, I want to find out what that “something” is. Which is why I keep reading.

4) If your main character is going to do something horrible, try to have someone else instigate it – Our hero, Dan, cheats on his beautiful amazing wife and adorable daughter. Ouch. Talk about a tough character to like. If you’re going to have your hero do something as reprehensible as this, make sure it wasn’t his idea. If he instigates it, we’ll hate him. It’s Alex Forrest (Glenn Close) who moves in on Dan here. She’s the one pushing him for lunch. She’s the one who suggests they’re “adults” who can make their own decisions. She’s the one who’s trying to make this happen. I’ve read a lot of scripts where a married or committed man goes out and fucks other women without a second thought. I immediately hated all those characters.

5) Give the wife something to do – Oh boy. If I had a dollar for every time a writer forgot about the wife character, I could buy a new car. Amateur writers write only with the actions of their protagonist and antagonist in mind. Pro writers give ALL OF THEIR CHARACTERS something to do. Fatal Attraction has wife Beth spearheading the big move from the city to the suburbs. She’s visiting potential new houses as well as prepping the sale of this apartment. This ensures that a second storyline is going on underneath the main storyline, which gives the script a more dynamic and realistic feel.

6) Sometimes, the absence of damage is worse than actual damage – Alex boiling the rabbit is one of the most memorable scenes in movie history. But if all you do is fill your thrillers with “boiling rabbit” scenes, they lose their effect. One of the creepier scenes in Fatal Attraction is when Alex picks up Dan’s daughter from school and spends the day with her. She doesn’t do anything to the little girl, dropping her off at Dan’s home unharmed, and yet it’s a horrifying scene.

7) STAKES ALERT – Remember that it’s your job to raise the stakes of your story wherever possible, ESPECIALLY in a thriller. The more there is to lose, the more compelling the situation will be. For example, this movie doesn’t pack the same punch if there’s no child involved. If the writer would’ve only written in a wife, we wouldn’t have been as involved. It’s the fact that he has a daughter, that he has a family, that gives our hero so much to fight for.

8) Don’t get so lost in the point of the scene that you forget the reality of the moment – I see this A LOT with amateur writers and even with good writers. We can get so set on achieving a scene’s purpose, we don’t stop to find the truth in the moment. For example, there’s an early scene in Fatal Attraction’s script where they need to set up the babysitter before the parents leave. This could’ve been a very perfunctory moment. “Okay, there’s the food in the fridge.” “She likes when you read to her.” “We’ll be home by ten.” That sort of thing. However, your job is to stop thinking of the moment as a movie scene, and to find its inner life, its “truth” if you will. So the writers add this nice little exchange where Dan says to the babysitter, teasingly, “And no partying, d’you hear?” The babysitter replies, “But I’ve already sent out the invitations.” Dan responds. “Can I come?” This exchange takes what easily could’ve been a straight boring “get through it” scene, and adds life to it. Make sure you go through all your scenes and find their reality.

9) Look for ways to cleverly intersect storylines – There are typically several storylines going on in every script (here we have the affair, the potential move to the suburbs, his job at the publishing house). It’s your job as a writer to look for fun ways to bring these storylines together. A great example of this occurs in Fatal Attraction. Because they’re moving, they must sell their own place, which means potential buyers coming in to look at it. Who better to be one of those “potential buyers” than… Alex Forrest! Not only that, but the way this scene is written, Dan comes home to find none other than Alex IN HIS HOME talking TO HIS WIFE. It’s a shocking reveal (and one of the most memorable moments in the script). Finding great intersecting moments like these are what really elevate a script.

10) In a thriller, your protagonist and antagonist must square off – In the much publicized original ending for Fatal Attraction, Alex Forrest kills herself and makes it look like Dan murdered her. That ending didn’t test well. Why? It’s hard to say. But a good bet is that when you have a battle like this going on for 110 minutes, the audience wants to see the hero and the villain square off against one another. So that’s exactly what they did with the reshoot. They had Alex come to the home and try to kill Dan’s wife. Dan battles her to defend his family. It was a much bigger and more satisfying ending.

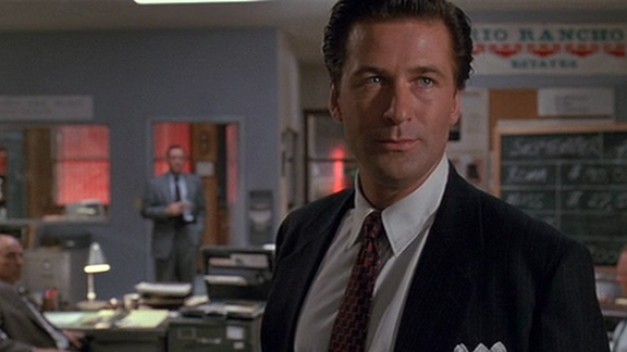

Glengarry Glen Ross is one of those films that flew under the radar because of its ultra low-budget look and feel. As moviegoers, when we don’t see our movie stars perfectly lit in front of A-level sets, we get suspicious. “Is this one of those vanity projects?” we ask? The kind where the acting is great but the story sucks? We’ve been burned by too many of those before so no thanks. But Glengarry is one of the few “vanity” projects that was also a great story (and a great film!). I mean superstar screenwriter David Mamet (who was paid 1 million to turn his hit play into a script) wrote the thing. And to many, this is his best work. There are, of course, three things that one remembers from Glengarry – Jack Lemon’s amazing performance, The Alec Baldwin scene (which was written exclusively for the film – it was not in the play) and the razor-sharp dialogue. In honor of that dialogue, I’ve decided to make today’s “10 Tips” all dialogue-related! Enjoy!

1) Your characters should only speak when they have something to say – Without question, one of the biggest mistakes I see from amateurs is characters who are only talking because they’re in a scene. If characters are only talking because a writer’s making them, the scene will be maddeningly boring. What’s so great about Glengarry Glenn Ross is that the characters never say anything unless they want something. They may want to close a deal, they may want to beg for leads, they may want to let their boss know how pissed they are, they may want to vent their frustrations to their co-workers, they may want to convince someone to steal the leads with them. But they’re always speaking for a reason. If your character doesn’t want anything, they probably shouldn’t be saying anything.

2) Use dialogue to reveal character whenever possible – When characters speak, try to occasionally tell us something about their character via dialogue. For example, Blake (Alec Baldwin) is gearing up for his classic monologue early in the script. He turns to Williamson (Kevin Spacey). “Are they all here?” “All but one.” “(checks watch) Well, I’m going anyway.” In other words, this is the kind of man who doesn’t have time to wait for others. That’s what we learn about Blake through this line of dialogue. You should try to reveal character through dialogue wherever you can.

3) Ask and you shall receive… a better response – When a character asks another character a question, the simplest answer is usually the most boring. “How are you?” “Good. How bout you?” If this is how your characters speak, God help you. You can do better. In the famous Blake (Alec Baldwin) monologue, one of the salesmen asks, “What’s your name?” “Fuck you, that’s my name. You know why, Mister? ‘Cause you drove a Honda to get here tonight, I drove a sixty-thousand dollar B.M.W. That’s my name (original dialogue).” What would you have written had someone asked Blake “What’s your name?” Hopefully something just as unique.

4) Specificity in monologues – Monologues, like Alec Baldwin’s, work best when the speaker is being SPECIFIC. This monologue would’ve sucked had the character unleashed something general like: “You guys are all lazy bums! We give you leads and what do you do with them? Jack shit! You need to stop fucking around and work harder to secure these guys!” There’s no specificity there. Anyone could’ve written that! In Mamet’s version, we learn about ABC (Always be closing), A.I.D.A (Attention, Interest, Decision, Action), we learn Blake drives a 60 thousand dollar BMW, we learn his watch costs more than what these guys make in a year, we learn he’s from Mitch and Murray, we learn about the coveted sparkling wonderful Glengarry leads. The monologue is convincing because it’s not just a bunch of general bullshit. It covers a lot of details. Make sure to do the same with your monologues.

5) Delay an answer to a question! – Just because a character asks a question during a conversation doesn’t mean the other character has to answer it right away. We see this during another great moment in the Blake monologue. Moss (Ed Harris) challenges Blake with, “You’re such a hero, you’re so rich, how come you’re coming down here, waste your time with such a bunch of bums?” Blake looks at him for a moment then keeps on yelling at everyone. A few minutes later, out of nowhere, he turns back to Moss: “And to answer your question pal. Why am I here? I came here because Mitch and Murray asked me to, they asked for a favor, I said the real favor, follow my advice, and fire your fuckin ass, because a loser is a loser.” A conversation is never a straightforward thing. It jumps around a lot. Never forget that.

.

6) CONFLICT CONFLICT CONFLICT – I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. One of the easiest ways to create good dialogue is through conflict. In almost every single scene in Glengarry Glen Ross, one character wants something while the other character wants something else. Take the famous scene where Shelley Levene (Jack Lemmon) begs Williamson (Kevin Spacey) for the Glengarry leads. The entire scene is built on the principle that Levene desperately wants those leads while Williamson is determined not to give them to him.

7) Phrase exercise – To find out your character’s unique way of speaking, take a simple phrase, then have your characters each say it in their own unique way. This is not to happen in the script. Do this in a separate document. The goal is to get a feel for how each of your characters speak. Take the phrase, “Good luck.” Let’s see how each of the characters in Glengarry would say this. Blake actually says in the script, ““I’d wish you good luck but you wouldn’t know what to do with it.” Bitter Shelley might say, “Good luck you miserable cocksucker.” Pathetic Williamson might say, “Good luck” laced with heavy sarcasm. Earnest Aaronow (Alan Arkin) might say, “Best of luck, Frank. You deserve it. You really do.” If each of your characters wouldn’t have their own way of saying a phrase, you either don’t know your characters well enough or you’re not doing enough with your dialogue.

8) A negative temperament for at least one character in a scene typically results in interesting dialogue – Some of the best scenes in Glengarry are when Shelley (Jack Lemon), wreaking of desperation, tries to get others to do what he wants (getting those Glengarry leads, trying to get the husband of the woman he talked to on the phone to come around). Whether it be frustration, desperation, fear, anger – Negative dispositions are your friends when writing dialogue.

9) Liar Liar, dialogue on fire – Dialogue is always interesting when someone’s lying. Why? There’s a natural inclination for us readers to find out if the other party’s going to figure it out or not. Glengarry is one big lying fest. Shelley’s lying to all the leads about how they “won” a contest. Roma (Pacino) spends the entire movie lying to his mark. Ross (Ed Harris) and Aaronow (Alan Arkin) are lying about robbing the place. When a character has something to hide, the dialogue always has an extra spark to it.

10) Give your character an interesting angle going into a scene – Instead of just placing two characters in a scene and letting them talk, try to find an interesting angle for your key character. So in the Glengarry restaurant scene, where Roma (Al Pacino) is trying to con a customer into a sale, there’s a million ways Mamet could’ve approached it. He could’ve had Roma be straight forward, he could’ve used the hard sell, he could’ve had him focus exclusively on the numbers, he could’ve made it seem like a great deal then played hard to get. Instead, he has Roma SEDUCE the man. He treats him like a date, someone he’s wooing. He slowly cuddles up to him, makes the man believe in him, and that’s when he goes in for the kill. Seduction, I believe, was the best option for interesting dialogue in this case. It allowed for all this fun philosophizing on life that you wouldn’t have gotten otherwise. If you want good dialogue, make sure your character is approaching what he wants from an interesting angle.

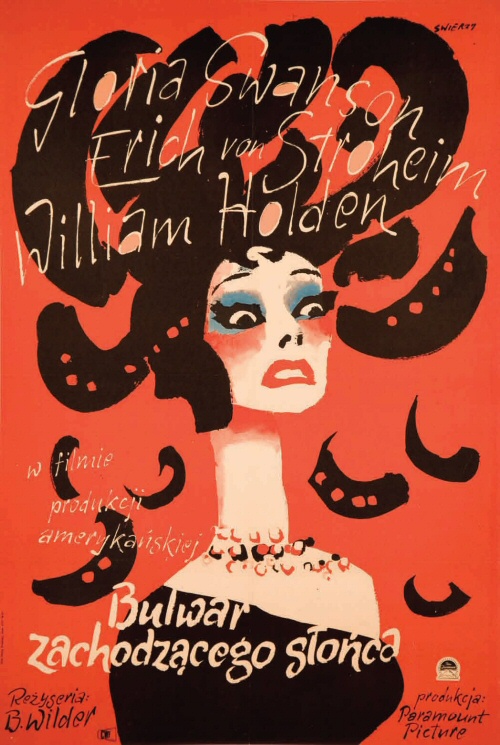

So, a dozen years ago, I said to myself, “If I’m really going to understand this industry, if I’m to be as knowledgeable in cinema-speak as everyone I run into, I’m going to have to watch every good movie ever made, even the ones I have no interest in seeing.” Which was a big problem for me because I didn’t like black and white films. They were all so over-acted and the lack of color instantly dated them, making it hard to fully immerse myself in the experience. People knock me on this, but movies are about suspension of disbelief. If at any point that suspension is broken, so is the magical movie spell. And black and white breaks the spell for someone who grew up in color. But I felt I owed it to myself to see all these movies, so I did. Outside of Hitchcock’s films and a few others, Sunset Boulevard is the only black and white movie where I forgot the black and white. There was something about the film, despite it being 50 years old, that felt so current. I’d never seen that with these old movies before. I’ve been aching to revisit it forever and “Ten Tips” seemed the perfect motivation. For those who haven’t seen the film, it’s about a down-on-his-luck screenwriter who accidentally befriends a washed-up silent film actress. I highly recommend seeing it if you haven’t yet.

1) Myth: You can’t write a movie about Hollywood – I used to believe this myth. But the truth is, you just can’t write a BAD movie about Hollywood. It doesn’t matter what the subject matter is. If you have great characters, a unique concept, a compelling plot, nice twists and turns, nobody’s going to say to you, “I thought your script was the best I’ve read all year. But I have no interest in it because it’s about Hollywood.” If something is good, people WILL WANT IT. I think the key to the “about Hollywood” script is the concept. Focus on something less obvious than your basic “screenwriter/actor trying to make it” storyline. Sunset Boulevard is about a struggling screenwriter who gets kidnaped into a fading actress’s house of horrors. It dealt with Hollywood from a different perspective. If this is had been about our hero, Joe Gillis, trying to get his movie made, Sunset Boulevard would have been forgotten two weeks after it came out.

2) Timeless movies are driven by characters with universal problems – The question I’ve constantly asked myself about this film is, “How come this 60 year old film still feels relevant today?” What is it that makes any movie stand the test of time? And I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s timeless characters – characters with universal problems that people are going to have today as well as have a hundred years from now. Norma Desmond is terrified of being alone. Joe Gillis is struggling to make ends meet. Betty Schaefer doesn’t know if she should be with the “right” man or the man she’s in love with. Give your characters relatable universal problems and they’ll last for ages.

3) Don’t expect a great movie unless you have a great character – The more I read, the more I realize that you shouldn’t even bother writing a movie unless you have a REALLY INTERESTING, UNIQUE, MEMORABLE character SOMEWHERE in your script. Those are always the scripts that actors are most interested in. Those are always the scripts that get made into movies first. Those always turn into the films you remember most. Sunset Boulevard is Sunset Boulevard because of the wacky crazy antics of Norma Desmond. The woman has a chimpanzee buried when we first meet her! What interesting shit does your character do?

4) Interesting characters tend to be supporting characters – Although I’ve seen movies with really wacky main characters, most of the time, the memorable characters are not the hero. Why? Because the hero has to be the straight man. He has to be the one to keep the story on track. He must be grounded. If he’s too wacky, the story becomes unfocused and messy. Jack Sparrow, Han Solo, Quint, Doc from Back To The Future, Norma Desmond. Supporting characters tend to work best in those secondary roles because they can be wacky without upsetting the balance of the story.

5) The intruding storyline – Remember that whatever your story is about, you want to have an “intruding” storyline, something that’s trying to make its way into your character’s life independent of the main plot. At first, in Sunset Boulevard, it’s the repo men. They’re constantly on Joe’s trail. They’re coming to Norma’s house. You need this intruding storyline because if all you have is your main plot, the script’s going to feel thin.

6) If an intruding storyline ends, replace it with another – This is where the real writers show their mettle. They know that certain subplots are going to conclude in the middle of the script, and when that happens, they need to replace them. So here, the intruding storyline of the repo men ends. What’s going to replace it? Wilder and his crew write in the Betty Schaefer screenwriting plotline, which intrudes bigtime on the main plot (and ultimately ends up in Joe’s demise!). You always want at least one story element intruding on the main plot, and probably more.

7) Great lines of dialogue tend to stem from character – “I am big. It was the pictures that got small,” is one of the most famous lines of dialogue in history. I spend entire nights, sometimes, trying to figure out what makes a great movie line. I still haven’t figured out any definitive formula, but Sunset Boulevard reinforced one of my beliefs: The best lines of dialogue stem from character. Norma Desmond is a narcissistic, delusional fame-whore who erroneously believes she’s still a star. Naturally then, when someone says “You used to be big,” she’s going to give a narcissistic, delusional fame-whore-like response: “I am big. It was the pictures that got small.” So when looking for that amazing line, start by asking who your character is.

8) CONFLICT ALERT – Remember that nearly every scene you write should have some element of conflict in it. Take a very simple dance scene in Sunset Boulevard. Norma Desmond has a “party” which she of course invites Joe to. When he gets there, there are no other guests. Just him. She then wants to dance. Joe does so, but reluctantly. The scene then revolves around this simple setup: She wants to dance, he doesn’t. You can see this dynamic extrapolated over the entire movie. Almost everything in Sunset Boulevard is about Norma wanting something and Joe not wanting it. This is the conflict that drives every scene, and by extension, the film.

9) Contrast the surrounding elements with the moment at hand – In that same scene, Joe and Norma get into a fight. The ugly battle is contrasted against the beautiful music from the live band. Contrasting the surroundings with what’s going on with the characters is always good for a scene or two in your script.

10) The Anti-Love Story – I’ve found that these “anti-love” stories are almost always interesting. By “anti” I mean a love story where one or both of the characters doesn’t want the relationship, but are stuck in it anyway. Movies like 500 Days of Summer, The Break-Up, War of the Roses, Sunset Boulevard. We’ve seen every love story in the book, which is why they all feel so cliché. Anti-love stories are much rarer, which is why they tend to be so fascinating when done well.