Search Results for: 10 tips from

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Thriller/Lifetime (Made-For-TV)

Premise (from writer): When her homecoming ends in tragedy, a desperate single mother spins a web of lies to protect the family nursery from a ruthless property developer.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Breaking into the industry through Lifetime MoW (Movie of the Week) means is legit. Many writers have started out there and transitioned into feature films. It’s a subject we’ve never covered on Scriptshadow in my 4 years there. We’re always focused on high concept studio-oriented stuff. Why not made-for-TV? That career path would make for an interesting discussion in your blog.

Writer: Brett Martin (Electric Dreamer)

Details: 105 pages (note: This is an updated draft from the one posted on Amateur Offerings) – Edit: I’ve been informed that I read the OLD draft. Take that into consideration when reading the review. Sorry about that, Brett!

Long-time commenter and awesome community member, Electric Dreamer, has bestowed upon the Scriptshadow community a challenge heretofore unknown to the reader faithful. To review a made-for-TV screenplay.

We talk about genre scripts and Oscar hopefuls and giant spec sales all the time, ignoring the fact that there’s a huge industry that exists below the line where writers make a living on, let’s just be honest here, guilty pleasure TV flicks. “The Day Janie Left” doesn’t just write itself, you know.

So I thought today’s review could double as primer for the made-for-TV world. If you want to play in the sandbox where the sand isn’t as deep, where you can develop your skills before moving up to the big leagues, then Made-For-TV might be for you. Let’s check out Electric’s “Reap What You Sow” to see what these films are all about.

30-something Gemma has just arrived back in her home town with her 15 year old cancer-stricken daughter, Rose. The two are flat broke and from the bits and pieces of their conversation we’re privy to, it sounds like Gemma is hoping to reconnect with her father, possibly even stay with him, a difficult decision since he’s always been an abusive alcoholic.

But when Gemma shows up at her childhood home, her father is dead, his neck pierced with a broken whiskey bottle. It would appear that he had a drunken accident.

OR DID HE???

When studly Sheriff and former Gemma boyfriend Carl Baxter comes to take a look at the mess, he’s not convinced that this was an accident. In fact, he’s suspicious of the fresh bruises that have appeared around Gemma’s neck.

COULD GEMMA HAVE MURDERED HER FATHER???

While Carl turns the dad’s death into an official murder investigation, Gemma learns that the richest man in town, Walt Sharpe, was just about to close a deal to buy Gemma’s house. It doesn’t take Gemma long to realize that Sharpe wants to build some giant resort, and that her father’s house is right in the middle of it.

Apparently, when the dad died, the contract disappeared. So Walt employs his right hand man, Butch Garner, to form a relationship with Gemma, allowing him access to the house where he might possibly locate this missing contract.

But then Butch starts to actually like Gemma, and everything gets redonkulous. This forces the increasingly psychotic Walt to try and get the house through other means. And through that pursuit, we learn the shocking truth behind who killed Gemma’s father.

Okay, I’m going to start off with some advice right out of the gate. Brett sent me a new version of his script, in which he says he completely rewrote the first 12 pages. I COULD TELL. And this is why I warn writers away from doing massive changes at the last second.

Screenplays are odd beasts. They don’t operate under the known laws of physics. You can look at a change you just made and think, “Wow, I really nailed that. That’s so much better than what I had before.” Then you pick up your script a week later, read the same scene, and it’s like a mentally challenged fifth grader hijacked your script.

What happened?

What happened was TIME. Time allows perspective. When you rush, you don’t have perspective. You can’t see how the changes fit into the larger picture yet.

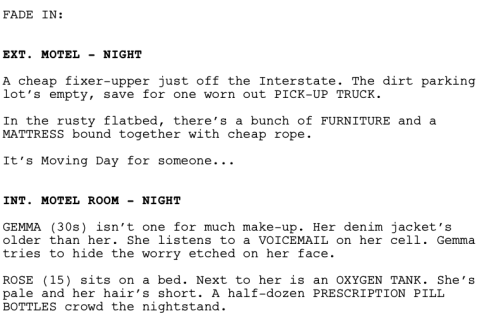

That’s clearly what happened here because once the script got going, it was fine. It was only the first few scenes that had me confused. For example, here’s the first half-page.

So we’re at a motel. Then we’re told of furniture and a mattress outside and that “It’s Moving Day for someone…” Is this an off-the-cuff description to add color to the writing? Or is this referring to specific character(s) we’re about to meet?

This early in a script, before you’ve identified the style or voice of the writer, you have to assume that everything is being written with a purpose. Therefore, I’ll assume the “moving” has to do with our characters (Gemma and Rose). But if it’s “moving day,” why aren’t they moving from their home? Why are we at a motel?

Maybe they’re in the process of moving? Like they’re on one leg of the journey? Except in the scenes that follow, there’s no actual moving that occurs. The point is, I’m stuck trying to figure something out that should be obvious. And I believe this mistake was made because of rushed writing.

I point this out in my book as one of my tips. Don’t make a lot of changes right before you send your script out. Something’s bound to get screwed up.

Moving on. Reap What You Sow is a very tight story. One thing I’ve realized about the Lifetime/Hallmark movies is that because they embrace formula so openly, they’re perfect for the GSU (Goal, Stakes, Urgency) approach. These movies DESPERATELY want you to use this formula. And they don’t care if it’s transparent.

So here Gemma has a goal – she has to get her late father’s garden/landscaping business up and running to secure the house. The stakes are if she fails, she loses the house. And the urgency is that she only has a month to do it or else Walt gets the home.

But Brett didn’t stop there. Brett use something I like to call GSU-squared (or even GSU-cubed). This is when you give GSU to EVERY SINGLE MAJOR CHARACTER IN YOUR SCRIPT.

So we know Gemma’s GSU plight. But we also have Walt’s. His goal is to get the house from Gemma. The stakes are that if he fails, he can’t build his super-resort. And the urgency is the same time frame that Gemma’s got (since they’re working off the same ticking time bomb – one month).

Then you have Butch. Butch’s goal is to find the contract. The stakes are his standing in Walt’s company. And the urgency is the same (1 month).

By giving every character GSU, your script is always MOVING. Whenever we cut to a character, they have something they’re trying to achieve. And because of “S” (stakes), that something is always important.

If you’ve ever found yourself cutting to characters and they feel boring or static, chances are it’s because they don’t have a goal, or there are no stakes attached to their goal, or there’s no time constraint involved in their journey. Give a character GSU and they instantly come alive.

So Brett did a really good job there.

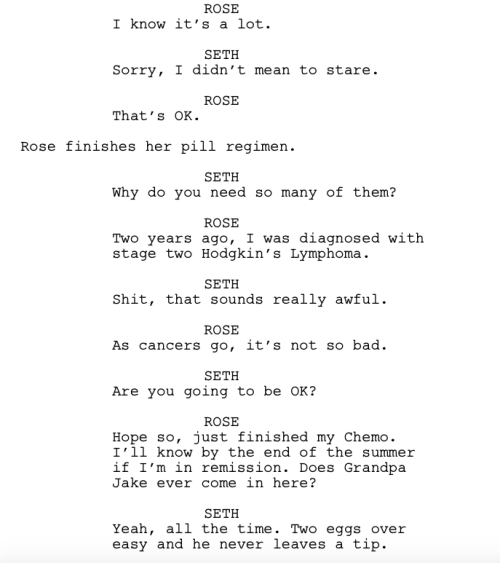

But where Reap What You Sow runs into problems is in its dialogue. And maybe this is because I don’t understand the expectations for dialogue in made-for-TV movies (the extent of my made-for-TV watching is limited to Mommy Dearest), but whether their expectations are low or not, there wasn’t enough LIFE in these words. Here’s a sampling from a scene in which Rose’s new crush, Seth, stares at her oxygen get-up.

It felt like dialogue. It never felt like people talking. And I think that’s because Brett didn’t know his characters well enough. Rose, in particular, seemed like she was only there to add financial strife to Gemma’s situation. I never saw her as a real person. And when you don’t get to know your characters, you don’t learn their little idiosyncrices, their fears and reservations – the things that inform how a person speaks.

For example, I read a script not long ago where a meathead character would pepper his speech with “you know” every five seconds, even when he didn’t need to. Or, to compare similar characters, there’s the character of Emma in the TV show, The Bates Motel. Like Rose, she needs a breathing apparatus.

Emma is infatuated with Norman, so every part of the way she speaks is geared towards pleasing him, impressing him, trying to get him to notice her. There’s a neediness to her speech pattern that brings her dialogue alive. Here in “Reap What You Sow,” characters speak mainly to move plot along or give opinions about things (i.e. “I don’t like Butch.”). There’s a lack of naturalism and a lack of fun to the dialogue.

And I don’t think this being a TV movie should be an excuse to write less-interesting dialogue. Sure, the dialogue’s probably going to be more on-the-nose than in, say, a David Fincher film, but you should still try to be on-the-nose with some flair.

I guess the best way to sum up my reaction to the dialogue here is that it felt like Brett was bored writing it. I want him to write a version where it feels like he’s having fun. And isn’t that what Lifetime wants anyway? Don’t they want a little cheese? A little goofiness? A little flash?

It’s nearly impossible for me to give a rating here because I’m trying to rate something that embraces a lower quality product. And while I definitely thought there was a lot to celebrate, the story wasn’t challenging enough to keep me engaged. That and the dialogue were what kept this from being “worth the read.”

With that said, I feel like Brett achieved what he set out to do, and I don’t see his script as being that far behind what Lifetime puts on the air. What did you guys think?

Script link: Reap What You Sow (new version)

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Brett hooked me up with a couple of writers who have operated in the Made-For-TV-Movie world. After promising each of them a box of Sprinkles cupcakes, they’ve shared with me some trade secrets. They say that Hallmark responds to scripts that promote the wholesome, family love, uplifting thing. While Lifetime is a little more varied. They prefer the tawdry woman in danger scenario. But also like domestic strife, standing up to invaders, and the storybook romance (an old flame rekindled). Any made-for-TV movie fans here? What other secrets can you tell us!?

How to avoid the “aimless riffing” issue that plagues Apatow’s newest film.

So I went to see Trainwreck last night and, holy shit was it boring! The trailer makes the movie look really good but that’s because the trailer does the one thing the film doesn’t do, which is to FOCUS THE DAMN STORY.

Judd’s biggest issue is his propensity to let scenes drag on for too long. If you saw Trainwreck, chances are, you felt the way I did – which is that the scenes never ended. While a script can survive one or two drawn-out scenes. It can’t survive a bunch of them. And it definitely can’t survive ALL the scenes being that way.

And I understand why Apatow does this. He’s very much a “workshop the scene” kind of guy. He’ll start with the scene as written, then play with it on set, allowing the actors to riff and try a bunch of jokes, the objective being to stuff as much comedy into each scene as possible.

Unfortunately, movies don’t do well with that plan. They like when everything is tight, focused, and to the point. They like when scenes feel like they have a purpose. So in honor of this terrible movie, and Apatow’s lazy approach to scene-writing, it’s time to remind ourselves what the principles of good scene-writing are.

1) Give your featured character an objective in the scene – The key character should have an objective in each scene. This is their “goal.” Play the scene out until the character either achieves or fails at this goal. As soon as one of those two things happens, the scene is over. Notice I said “key” character and not “main” character. That’s because sometimes, someone other than your main character will have the objective in the scene. For example, if your main character gets called into their boss’s office to get fired, it’s the boss’s objective that’s driving the scene (to fire your main character).

2) Get in late, get out early – Good God could Apatow have benefited from this Screenwriting 101 advice. The main reason scenes drag is that you either came into the scene too early or stayed with the scene way too late. Once you know what your key character’s objective in the scene is, try to start the scene as close to that objective as possible (unless you’re trying a specialized dramatic technique – more on that in a sec). So to use our “firing” scene again, get us in that scene right when the boss is about to fire her! Then, once that’s done, cut to the next scene! In Trainwreck, after the boss had fired Amy, we actually STUCK AROUND as two co-workers entered the scene and asked if Amy had been fired yet. It was an attempt to be funny but no one laughed because the objective had already been reached. Whether Apatow knew it or not, he had signified to the viewer that the scene was done. Now had those co-workers walked in and asked this question BEFORE the firing had happened, it might’ve worked (and that actually sounds like it would’ve been funnier). But you can’t do that after all the air has already left the balloon.

a. (Specialized Technique) – Yes, you typically want to come into a scene as late as possible. But there are some instances where a drawn-out scene opening can work. For example, if you utilized some dramatic irony and informed the audience ahead of time that Amy was getting fired (something Amy doesn’t know), now when Amy walks into her boss’s office, you can introduce a few pages of conversation before the firing happens. Why? Because you’ve added the element of anticipation. We know the bomb is going to go off, so there’s an added element of tension to the interaction. So yes, you can ignore the “get in late, leave early” rule (just like you can ignore any rule). But you should have a good reason for doing so.

3) Conflict – This, Apatow knows how to do. He knows that in every scene, there needs to be some sort of conflict driving the scene. Without conflict your characters aren’t trying to work through anything – aren’t trying to come to a conclusion on anything – which leaves the audience wondering why the scene is being included. You could feel conflict in Amy’s scenes with her first boyfriend (John Cena), who liked her more than she liked him, in the scenes with her father, who was always butting heads with Amy about her life, with her sister, who she didn’t see eye-to-eye with on anything, and with the main love interest, who she was afraid to fall for, leading to her sabotaging their interactions. Conflict is good, folks. Use it!

4) Stakes – The higher the stakes are in a scene, the better. If nothing’s on the line, the scene will feel pointless and boring. Obviously, not every scene can be of Level 100 importance. Your main characters can’t be about to break up every single time we’re with them. So you have to stagger the intensity level of the stakes. But there should always be SOMETHING on the line. I recently read an amateur script where two co-workers were kind of hungry so they went to get some pizza. On the way there, the subway train broke down, and we stayed with them for the next four pages as they tried to figure out how they were going to get their pizza. So our two characters weren’t even that hungry. They didn’t have anywhere important to be. They decided to get pizza on a whim. The train broke down, preventing them from getting their food…. Why is this scene supposed to interest us? It doesn’t. Because there’s nothing on the line. You gotta add those stakes, people.

5) Urgency – Urgency is probably the least important of all the scene tips I’m offering today, but don’t underestimate its power. If you put a timer on a scene, you can really add some life to it. Couple it with some high stakes and, baby, you’re cooking with gas. If, for example, in the aforementioned subway scene, we changed it so that our two workers were trying to make it across town for the biggest meeting of their life? If not making it to that meeting meant their company lost a 400 million dollar deal? And they only had 10 minutes left to get there? Now you have a scene that people are going to care about.

6) Necessity – Finally, make sure the scene you’re writing is necessary in the first place. The worst scene is the one that doesn’t need to be in your movie. To know which scenes you need, know what your main character wants in the movie. What’s his goal? In Die Hard, John McClane wants to save his wife from the terrorists. So if you include a scene where John McClane goes swimming in the building’s swimming pool, that scene’s probably not going to play well, is it? That’s because it doesn’t get Johnny closer to saving his wife. Where I see this mistake the most is when the writer doesn’t know what their movie is about in the first place. Since they don’t know what their hero’s after, they can’t plan which scenes are needed to get them there.

Feel free to offer your own scene secrets in the comments section. For example, sometimes you want to “turn” a scene so that it goes in a different direction than the audience thought it would. This is really important in comedy. I was watching Modern Family the other day and uptight married couple Phil and Claire get stuck on a double-date at a nice restaurant with their hillbilly neighbors. You think you know where this is going (the hillbillies are going to cause a scene, being loud and boisterous, embarrassing Phil and Claire), but instead, the hillbillies bust out a nice bottle of wine, have a stellar rapport with the wait staff, and begin bragging about their son being accepted to Julliard.

Don’t just help your fellow writers with these tips, help Judd Apatow. The guy definitely needs to improve his scene work.

It’s a busy day here at Scriptshadow. I’ve been checking out the Scriptshadow 250 entries as well as finishing up some consultations, so I don’t know how long this article is going to be. What I can say is that I’ve already started to spot some common mistakes in the entries and I want to make sure they don’t keep happening. So today, I’m giving you three tips that should help improve your Scriptshadow 250 entry as well as make you a better overall writer. As always, I offer this reminder. Be mindful. With great power comes great responsibility.

ALWAYS FIND FRESH TAKES ON OLD TROPES

There are certain tropes in screenwriting that are unavoidable. They seem to go hand-in-hand with the genre they’re written in and there isn’t anything wrong with that. What is wrong, however, is giving the reader the same old version of the trope. It’s your job to find a fresh take on it, something that makes it feel new and exciting, and not business as usual. Take the well-worn cliché of a down-on-his luck gambler whose bookie sends his thugs in to demand a payment. This scene often takes place at a bar, or maybe just outside of the character’s apartment as he’s leaving. The bookie slams him up against a wall and says, “You’ve got 1 one week to find the 50 grand. Or else you’re dead.” Sound familiar? Yeah, if you knew how many times I had to read this scene, you’d never write it again.

The thing about the “fresh take” approach is that it requires NO EXTRA SKILL on your part. You don’t have to be more talented or more experienced. The only thing it requires is time and effort. For that reason, there should be no excuse. I read a script once where our main character was at a school function, watching his child run around and play with the other kids, and the bookie arrived, dressed just like any other parent (his tattoos still peeking out of his shirt though). He very quietly and calmly stood next to our main character, and, while watching the children, proceeded to tell him that he was going to kill him in 5 days if he didn’t come up with the money. The irony of a bookie demanding money juxtaposed against the innocence of kids playing was exactly the fresh take the doctor ordered. If there’s any trope you come across – any plot beat that you’ve seen in a lot of films – it’s your screenwriting DUTY to do something fresh with it.

WRITE YOURSELF INTO CORNERS

I’ve been reading a lot of scenes, lately, where the writer writes his hero into a “tough” situation that isn’t tough at all. Therefore, when the character makes his incredible “escape,” it’s as exciting as watching reruns of Two and a Half Men. What’s happening here is that the writer’s scared to make things too difficult for their hero, lest they not be able to figure out a way to get him out of trouble. What the writer doesn’t realize is that the reader always feels this. They know you’re playing it safe. Which is why the character’s escape lacks suspense.

From this point forward, be bold. When your character is facing a bad situation, make it as bad as it can possibly be, even if, at first, you don’t how you’re going to get them out of it. It’ll be scary, but that’s exactly what you want. If you’re unsure, the reader will be unsure. Then, like a detective, write down a list of the ways the character might get out of the situation. It won’t be easy, and it shouldn’t be. If the solution comes to you right away, the situation wasn’t dangerous enough. But eventually you’ll figure it out. Recently I read a script where the co-pilot of a small plane planned to kill his captain. The co-pilot sabotaged the plane, grabbed a parachute, and jumped out. The captain, while admittedly having to hurry up before the plane plunged into a field, merely had to find the other parachute and jump to safety. I told the writer to have the co-pilot tie the captain up before jumping. And I told him to have there only be one parachute, the one the co-pilot took. Do I have any idea how the pilot’s going to get out of that situation? No. Which is exactly why I’m a lot more interested in what happens next.

FLIP THE SCRIPT IN A SCENE

You may have heard me mention that I’ve been watching House of Cards recently. Watching the episodes one after another has allowed me to catch a few of their tricks. One of the moves I notice a lot is the “flip-the-script” scene. This is where it looks like one character is in control of a scene, only for a “twist” to occur at the scene’s midpoint that results in us realizing the other character was in control the whole time.

For example, there’s a (non-spoiler) scene where a reporter from the Washington Post is at a bar, and this beautiful woman starts flirting with him. For the first half of the scene, she’s completely in control, manipulating our helpless reporter with her looks and sexuality. Then, just as it’s looking like he’ll succumb, he casually pulls out a picture of a girl he’s been looking for and places it in front of the woman. He asks her if she’s seen her. It turns out our bar woman was an escort who walked in the same circles as the girl our reporter was looking for. All along, he was playing her. The simple truth is that if every scene goes according to plan, you might as well put a “nap” tag on your script. “Flip-the-script” scenes send a jolt into the scene, and by association, the story, letting the reader know that not everything will go according to plan.

Genre: Contained Thriller/Sci-fi

Premise: (from The Black List) A corporate risk management consultant is summoned to a remote research lab to determine whether or not to terminate an at-risk artificial being.

About: Today’s script finished on the lower half of the 2014 Black List. Seth W. Owen is a writer and director whose debut film was 2010’s Peepers, about a rag-tag group of guys who try to spy on naked women. Ummm, not the most sympathetic setup for a group of lead characters. Luckily, this script is nothing like that. “Morgan” just landed Kate Mara and will be the directing debut of Ridley Scott’s son, Luke Scott. Presumably, the father pitched Mara to his son, since Ridley’s working with Mara on his new sci-fi project, The Martian.

Writer: Seth W. Owen

Details: 113 pages

There’s something about a script that starts with a character heading to some isolated unknown potentially dangerous location that gets me every time.

The anticipation of what lies ahead just tickles my insides. It never fails.

Add on top of that a contained thriller element that I HAVEN’T SEEN BEFORE, and you can officially color me hooked. Most contained thrillers involve a haunted house or characters stuck inside a place they’d rather not be. Pretty standard stuff. Today’s script injects a new twist into the scenario by giving the main character the power of God. She can, with the flick of her pen, destroy everything this group has worked so hard for. This setup adds some funky fresh wrinkles to the contained thriller genre, one of which dramatizes the hell out of the story. More on that in a minute. But first, let’s recap the plot.

When artificially intelligent “Morgan” – a sort of robot-bio hybrid – attacks one of the members of the team who created her, the company funding the project sends the strict and professional Lee Weathers (a woman – noooo! not another female protagonist with a male name!) out to Grant Farms, the home of the experiment, to assess whether Morgan should be put down.

As you might expect, the resident members of the project are not excited by Lee’s arrival. They’ve been working on Morgan for 5 years. This woman has the power to not only destroy everything they’ve built, but end their jobs. To them, she’s far more dangerous than anything Morgan might become.

Leading the team is the short and jittery Ted Brenner, an insect of a man who hovers around Lee, constantly assuring her that everything is “fine.” There’s Dr. Simon Ziegler, the unkempt lead designer who is the de facto “father” of Morgan. There’s the free-spirited Amy, the lead behaviorist. There’s the elusive Dr. Nagata, who never seems to be around when she’s needed. And then a half dozen other folks working on the project, which is all taking place inside a retrofitted mansion in the middle of nowhere.

While Lee’s job is to assess Morgan, it’s when she interviews the team members that she discovers something amiss. Namely that everyone has a verrrrry close connection to Morgan – some creepily so. As the truth begins to surface – that these people will do anything to prevent Lee from terminating Morgan – Lee must decide what’s more important. The company? Or her life?

Newcomer Anya Taylor-Joy will play Morgan

Newcomer Anya Taylor-Joy will play Morgan

Today’s lesson is all about TENSION. Why is it called “tension?” Because it’s TEN time more effective than “nosion.” “Nosion” is when you don’t have anything working under the scenes. Everything plays at face value – people’s intentions, their interactions, their motives. A “How are you doing?” literally means, 100%, “How are you doing?” Since it’s all at face value, it’s all BORING.

The brilliance of “Morgan’s” setup is that it BUILDS TENSION INTO THE STORY AUTOMATICALLY. Not a single person in this house wants Lee here. Therefore, every single scene has tension working underneath it. In these cases, “How are you doing?” could easily mean, “I don’t fucking want you here but I’ll play the game until we get rid of you.”

This is something all of you should take heed of – using your setup to do the work for you. I brought this up yesterday in the Breaking Bad article. Walt and Jesse have some great conflict-heavy dialogue throughout the series. That dialogue doesn’t happen because at the beginning of each episode, Vince Gilligan says, “Okay, how can we create conflict between these two?” Their conflict is already there. It’s built into the setup. Therefore, going at it is a natural byproduct of their interactions. Good dialogue just happens.

Same thing with “Morgan.” Owen doesn’t have to sit there and wonder how to create tension inside the house. He’s built the tension INTO THE SETUP by sending a woman in to determine the fates of a dozen people. How could that NOT produce tension?

This script is chock full of tips actually. Take the moment when Lee first meets Morgan. We haven’t yet established Mogan’s reason for being here, and Owen decides to do so in this scene. The mistake the amateur writer makes here is having the protagonist narrate her own backstory (“I’m here from blah blah on orders from blah blah corporation…”). Instead, it ALWAYS SOUNDS BETTER when you have the OTHER character say it. So in the script, Morgan says, “Hello Lee.” Lee replies, slightly surprised, “You know who I am.” Morgan says, “Yes. Of course. You’re Lee Weathers. Risk Management Consultant at Omnicron.” “And why I’m here?” “To assess my viability as…” and so on and so forth.

There are more juicy dialogue tips if you pay attention. In a later scene, the house chef and Lee are talking, and Lee is giving noticeably short answers to all his questions. The less experienced screenwriter always writes the on-the-nose reaction to behavior. They’d have the chef say something like: “You don’t talk much do you?” The experienced screenwriter writes the sarcastic less obvious reply, which is what Owen does here: “You’re kind of an over-sharer, huh?” It’s just a way more fun response. Like I’ve said before – If your characters are constantly giving the obvious response, there’s a good chance your dialogue is boring.

The script stays exciting despite the contained location, mainly due to that tension I referred to earlier and also because Morgan is a ticking time bomb. You know she’s going to explode at some point. And you want to be around when it happens.

The only issue I see in the script is that the story kind of gets taken away from Lee for a portion of the second act. It feels like everyone else is starring in the movie except Lee for awhile. A new character even comes in and has a 12 page one-on-one scene with Morgan. It’s a good scene with a great payoff but it’s always risky to demote your main character to passive observer for a long period of time. More than once I found myself asking, “Where’s Lee right now?” In the rewrite, you probably want Lee at least trying to interject and stop this interview when it starts going downhill.

It’s no secret I love these types of scripts (The Story of Us, Ex Machina) so I’m probably not surprising anyone here. But this script took a different approach to a genre that could potentially feel played out and that’s a big part of what kept me entertained. Really good stuff here!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A good setup should do the work for you. If the tension or the suspense or the conflict or whatever device you’re using to entertain a reader, isn’t built into the concept, it’s going to be hard to incorporate it into your scenes. So if in the original conception of Breaking Bad, Walt and Jesse were best friends with similar interests, then trying to write a bunch of arguments between them would feel false. You’re forcing conflict that isn’t there. But if your setup includes two opposites, two people who don’t see eye-to-eye, then arguments are inevitable. This may seem obvious, but a lot of times I see writers working hard to create tension or suspense in a scene and it’s not working because there’s no tension or suspense inherent in the concept.

Five amateur screenplays. Read and tell us which one you liked best in the comments section. The winner gets a review. Also, feel free to offer constructive criticism to the writers.

Title: Molniya 7

Genre: Sci-fi, Adventure.

Logline: A reckless American astronaut risks everything to save seven world leaders trapped on board a crippled Russian space station before it crashes to Earth.

Why You Should Read: Hi Carson, my name is Tony and my passion for movies and screenplays spans decades. I’ve analyzed hundreds of works and read dozens of books on the craft — especially your book, which is the best ten bucks I ever spent, (wink, that’s worth a read, right? )

Your mission, Carson, should you decide to accept it, is to open the attachment to this email and immerse yourself in this high concept adventure about ingenuity, human spirit, and the will to live. I’ve kept the read under 100 pages, yet made sure every character has something to do — actors will love this, and I guarantee you that there is stuff in this screenplay that even you have never before seen. — As always, should you or any of your subscribers be caught or killed, the secretary will disavow any knowledge of your actions. This email will self-destruct in five seconds. Good luck, Carson.

Title: Quiescent

Genre: Sci-Fi Adventure

Logline: After a long-dormant Atlantean power station buried under Manhattan for thousands of years transforms the city with a mysterious time-meshing force, a vision-haunted Native American tunnel worker, a Columbia geology professor and his beautiful assistant team up with a hardened CIA agent to shut the pyramid down before it destroys the planet.

Why You should Read: Quiescent is a labor of love that took me years of research and a ton of rewrites to complete to my satisfaction. A sci-fi action adventure with a strong male and female protagonist, rich in history, memorable characters and deep metaphysical undertones. The threaded mysteries of time, ancient Atlantean technology and Native American spirituality make this tale an exciting thrillride.

Title: The Battle of Mirbat

Genre: War / Action

Logline: A retelling of the 1972 battle in which eight special forces soldiers defended an Omani town against 400 heavily-armed guerillas.

Why You Should Read: Described as a latter-day ‘Zulu’, the Battle of Mirbat is an incredible account of valor in the face of overwhelming odds. Classified for over thirty years, the soldiers’ mission has only recently become public knowledge but hopefully this script will bring their remarkable tale to a wider audience.

Title: Hadleyville

Genre: Western

Logline: An idealistic Easterner journeys to the burgeoning Western frontier where he falls for a prostitute and gets in the wrong with a powerful businesswoman, forcing him to learn how to leave his idealism and civility east of the Mississippi.

Why You Should Read: While I know the Western isn’t (and hasn’t been for arguably 40 years) the most topical, profitable, or popular genre it used to be, it still has a certain appeal for writers looking to explore ideas that other time periods aren’t necessarily designed for. The lawlessness, the encroaching border of a growing nation, the differences between Eastern civility versus frontier survival: Where else but the Western can you touch upon these concepts?

I’ve been writing screenplays for about five years now (and have a B.A. in screenwriting if that means anything…). I’ve had two features optioned and was hired to re-write a feature — all by indie producers looking for ever elusive financing. On top of that, I’ve been a quarter-finalist, semi-finalist, and finalist in national contests, including BlueCat, Big Break, and Table Read My Screenplay. Hadleyville, in fact earned me a spot as a finalist in The Black List’s 2014 Cassian Elwes Independent Screenwriting Fellowship — I’m sure the fact that it’s one of the (if not the) highest rated Western on blcklst.com gave me a leg up there.

The point is: I know how to write a screenplay, good ones even, but I’m looking to heave myself over the hump into the lands of “Very Good” and “Great.” I have my degree, hours of writing and reading scripts, and tips from Script Shadow to improve my writing — but there’s something I’m missing. Something I can’t get a bead on. And I have no doubt that you (and fellow Script Shadowers) can lead me into the sunsetting happy ending.

Title: The Irish Rover

Genre: Comedy

Logline: Looking to connect for the first time, a son and his drunk, crotchety, dying Irish father take an epic journey to Ireland to get him laid for a final Father’s Day goodbye fuck. Mayhem, whorehouses, shootouts, and rollicking celtic music all ensue in the process of this father and son finally coming together.

Why You Should Read: Fred Seton and I wrote this about two years ago. We took this to only one producer (who we love), got him attached, and the project fell apart. It’s just been sitting collecting dust ever since. Fred wrote “Pierre, Pierre” and recently had his script “Kid Leviathan” that he wrote with Peter Hoare on the Hit List. “The Irish Rover” is a raunchous romp of an Irish R-rated comedy that was originally dreamt up for Robin Williams and Chris O’Dowd to kill it in. The script is insane, wild, got heart, and beers for everyone. It’s a place where you’ll find Van Morrison, The Pogues, the Dubliners, and Ween all getting hammered and playing at the bar. Cheers to the Blarney Stone!