Search Results for: 10 tips from

I was going to do my yearly post of the best movies of the year, but you know what? I don’t wanna. “Best Of” lists are boring to me right now. And if I’m bored, then my posts are definitely going to be boring. So instead, I’m going to share some screenwriting advice with you. Now that excites me. Helping all of you become better writers. For those who just have to know, however, here are my Top 10 films without explanation.

10)Captain America: Winter Soldier

9) The Equalizer

8) Blue is the Warmest Color

7) Guardians of the Galaxy

6) In a World

5) John Wick

4) Gone Girl

3) The Skeleton Twins

2) Philomena

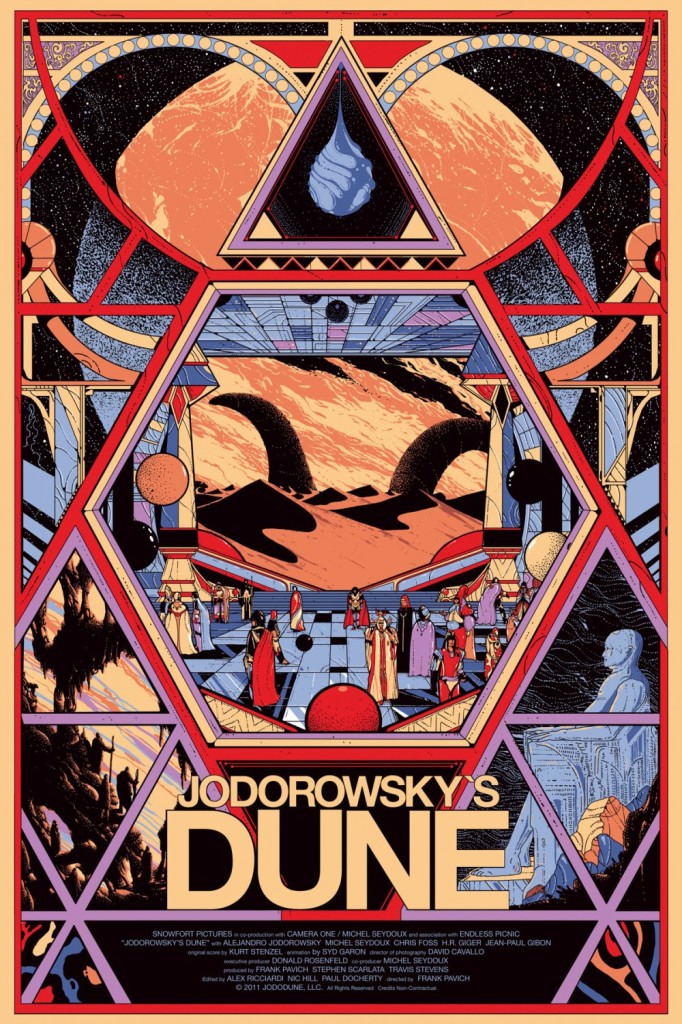

1) Jodorowsky’s Dune

Did not yet see: Nightcrawler, Boyhood, The Imitation Game, Foxcatcher, Lucy, Whiplash.

Now let’s talk about something that can actually help you. How bout a hefty dose of DIALOGUE ADVICE? Yeah! Nobody offered you that over the Christmas holiday, did they? You see, the other day, I was giving notes to a writer, and the dialogue in the script wasn’t up to par. Dialogue is always the hardest thing to help a writer with because it’s the subtleties that make it or break it. And most subtleties are intrinsic, making them hard to dissect and explain. This is what people mean when they say some writers have an “ear” for dialogue. What they really have is an ear for the subtleties of conversation.

So I had to take a few hours off, go through old sets of notes, pick out tips I’ve given before, look for new solutions specific to this writer’s problems, and package it all in a way that would help this writer dramatically improve his dialogue. The end result was more comprehensive than I expected, so I thought I’d share it with all of you. With that, here’s what I wrote…

The big weakness here is dialogue. There are too many on-the-nose, melodramatic and cliché lines. Here’s an example from Hunter and his son, Nicky (note to readers – part of the backstory here is that Hunter’s wife died).

Nicky: “Wish I could’a protected her that day…”

Hunter: “Me too, Nicky… me too.”

Let me ask you this. Is there any doubt that father or son wished they could’ve done more to save mom? Of course not. Therefore, to say it out loud is the definition of “on the nose.” This is followed by an extremely cliché echo-line. “Me too, Nicky… me too.” The echo-line has been used so many times throughout history that by this point, it’s only used as parody. I’ve personally seen the guys on South Park use it endlessly. Stay away from on-the-nose lines (characters saying exactly what they think/feel) and any line you’ve seen used more than a handful of times in other movies/shows.

Here’s another line (note to readers: our protagonist, Colin, accidentally killed a child while trying to save a group of people. Claire, our romantic interest, has just tried to convince Colin that it was an accident and there’s nothing else he could’ve done).

Colin: “He was just a little boy, Claire! His whole life ahead of him.”

Take note of how familiar and melodramatic this line is. It feels like something out of a soap opera. Also, once again, we know he was a little boy. We know he had his life ahead of him. Therefore, stating it out loud is on the nose and obvious. If you find your characters saying exactly what they’re thinking, exactly what they’re feeling, or anything that’s obvious, you’re probably writing bad dialogue. So how do you make this line better? In this instance, I wouldn’t have had Colin respond at all. As Claire tries to convince him it was an accident, I would’ve had him take it in. A look of frustration or disagreement, then, is all you need to convey his feelings on the matter. Often times, the absence of dialogue is the best dialogue option.

Overall, the dialogue here needs to be more unpredictable. It needs to be more natural and messy. Moving forward, I would suggest studying dialogue on a much deeper level. Start by writing down all your favorite dialogue-centric movies, then reading those scripts and noting where you liked the dialogue, then trying to figure out WHY you liked the dialogue. For example, a writer whose dialogue I’ve come to enjoy always inserts a unique phrase where a generic one would typically be. So instead of writing, “Joe went bar-hopping,” he might write, “Joe’s down at the strip of broken dreams.” Yet another writer reminded me how important specificity is when it comes to dialogue. A character shouldn’t say, “I need cereal.” He should say, “I need Tony the Tiger.” Paul Thomas Anderson, who many consider to be a dialogue master, says he rarely lets his characters finish sentences. He constantly has them interrupting before the other character finishes, as that’s more like real life.

I would go to coffee shops and eavesdrop and write down, verbatim, what people are saying to each other. Pay attention not just to what’s being said, but what’s being implied, aka, the subtext. “That’s a nice new purse,” doesn’t always mean, “That’s a nice new purse.” It might mean, “Looks like your sugar daddy’s treating you well.” Compare all this dialogue to your own dialogue. Figure out why yours doesn’t have the same naturalism.

I would spend every day writing a few practice dialogue scenes. Experiment. Take chances. Be creative. For example, write an entire scene with dialogue you’ve never heard before. Write an entire scene focused on subtext. Write an entire scene focused on suspense. Compare your scenes to scenes from professional scripts and note the differences. Pay specific attention to word choice. What words are the professionals using that you’re not?

Try to create scenarios where there’s conflict or tension between characters, as both result in more interesting conversations. Create secrets for your characters, so there’s subtext to what they’re saying. For example, in your script, Claire tells Colin right off the bat that she’s dying. Instead, what if you only give this information to the audience, and now when she meets Colin, she DOESN’T tell him she’s dying. Now the dialogue will be a lot more interesting. We’ll fear for Colin as he falls for Claire, knowing he’ll be devastated when he finds out the truth. Dialogue is one of those things, unfortunately, that doesn’t have a quick fix. It’s the culmination of a lot of small discoveries. But it’s not an area you can hope readers will overlook. Bad dialogue is one of the easiest ways to identify an amateur screenplay, so you have to put a lot of effort into getting it right.

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: After a man’s wife and daughter are brutally raped and murdered, his humanity disappears, and his lone goal in life becomes revenge.

About: The original “Death Wish” was made in the 70s with Charles Bronson. It was so successful, it inspired four sequels. The remake is one of the first movies Joe Carnahan wanted to make after the success of The Grey. The movie has had its trials in search of a green light though, as Carnahan really wanted rising star Frank Grillo to headline, but MGM wanted the eternally bored Bruce Willis. So Carnahan went and made the indie “Stretch” instead (about a stretch limo driver). But of all the movies on his upcoming slate, Death Wish is the one he wants to make most. And you can see that here in his writing. There is a hardcore love for this material on every single damn page.

Writer: Joe Carnahan (inspired by the novel by Brian Garfield)

Details: This looks to be an early draft, as it tips the scales at 141 pages (9/12/12).

With Grillo moving up the star chart, might Death Wish still happen with him and Carnahan?

With Grillo moving up the star chart, might Death Wish still happen with him and Carnahan?

Even when Joe Carnahan has operated inside the Hollywood system, he’s always managed to keep one foot outside of it. You can sense his disdain for the rules and it’s what’s allowed his movies to always feel a little off-kilter, a little different from the rest of the pack.

I think Carnahan’s secret sauce, the thing that allows him to distinguish himself, is that he’s unflinching. He’s not afraid to push you to the place you feel least comfortable in. We don’t like how raw and real Ottway’s contemplation of suicide is in The Grey, how bleak his outlook on life is. But that’s exactly what’s so different from everything else we watch – the safe “don’t worry, this is just a movie” sheen that Hollywood always sprays its films with isn’t there with Carnahan.

Death Wish is no exception. This script has the harshest rape scene I’ve ever encountered. And yet, it’s not what you’d think when you imagine the harshest rape scene you’ve ever encountered. I’ll get to that more later, but let’s lay out the plot first.

40 year-old Paul Kersey is a kick-ass trauma surgeon. He not only saves lives, he cares about the people he saves. Even if you’re a 17 year-old street banger, you get Paul’s full attention when he’s trying to keep your heart pumping.

But Paul isn’t perfect. He’s a coward. We see this early on when he and his wife are at his daughter’s basketball game and he gets into it with the father of one of the opposing team’s players. The ripped father challenges Paul to a fight and all Paul can do is back down and apologize. He may be superman at the hospital. But he’s Clark Kent outside of it.

After the game, Paul preps a secret present he’s giving his daughter for her birthday, but while taking a nap, Paul wakes up to a brutal beating. He’s being tied up, and he can hear awful things happening upstairs. Still dazed, Paul is helpless in his attempts to fend off his attackers, and watches as gasoline is poured everywhere and the place is set afire.

Paul passes out, but wakes up, ironically, on a surgeon’s table. Except now he’s the one whose life is being saved. After surgery, Paul learns the devastating truth. His wife and kid were raped and killed. With their deaths, the old Paul dies as well. In his place is a new Paul, a Paul who is anything but a coward.

Paul lies to the police (one of whom is his brother) about his attackers, saying he remembers nothing about them. He then sets about getting revenge. He goes out and buys a gun. He learns how to shoot. He gets in altercations with street thugs, and he starts his investigation.

Paul will find the people who took his two girls away. And he will make them pay. He will fucking make them pay.

Man, this script is BRUTAL. Carnahan takes the Taken approach where he utilizes the entire first act to set up the family. He knows that you’re not going to care if a wife and daughter are killed if you don’t know them.

So he sets up this loving marriage. He sets up Paul’s surgeon job. The great neighborhood they’re in. The daughter’s birthday party. Everything just seems…. Perfect.

And that’s partly why that rape/murder scene hits so hard. But why is this particular rape so memorable? Because we don’t see it. I’m not even sure we hear it. Carnahan makes a shocking choice when the attack on Paul occurs to SWITCH TO FIRST PERSON POINT OF VIEW. So we’re now inside Paul’s mind. And it’s terrifying because he’s disoriented and he’s just woken up and he’s getting beaten and he thinks he hears his wife screaming upstairs.

Some of you might say, “That’s just a gimmick.” But it’s not if Carnahan is using it to help convey how it will appear on-screen. I’m assuming we’ll be in close with Paul from this point forward. We’ll get close-ups, we’ll be right behind him. In a sense, WE’LL BE HIM, and that’s what this first-person writing conveys.

But afterwards, as Paul starts plotting his revenge, Death Wish runs into its first problem. There have been a lot of movies like this already – most of them inspired, ironically, by the original Death Wish.

You have The Brave One. You have Edge of Darkness. You have The Equalizer. You have John Wick. You have the Taken franchise. You even have Batman, which is, in a lot of ways, the same premise. This is a crowded space. So I could see a studio being like, how do we make this different?

And to Carnahan’s credit, he puts it all out there. I mean he is a really fucking great writer. He can do it all. He can write prose. He can write action. He can write dialogue. He can write characters.

Here’s his description of Paul’s co-worker…

“He meets the gaze of JANINE RAY, 30s, Chief anesthesiologist and proof that sometimes long hours, constant stress and sheer exhaustion simply cannot dent or diminish great beauty.”

I have seen the bad version of this description a couple hundred times in my life. It goes something like this: “JANINE RAY, 30s, was once beautiful, but time and stress have worn her down.” That gets the point across. But Carnahan’s version INSTALLS the description in you.

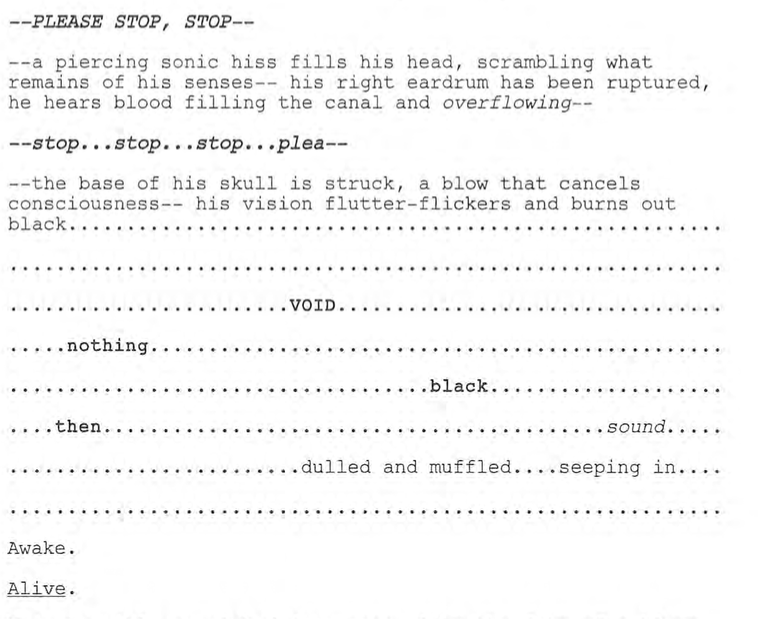

And here’s a section of the rape scene where Carnahan pulls out all the stops to convey the chaos in the house. This is not how you write if you’re looking for a paycheck. This is how you write when you’re giving a script everything you’ve got.

Ironically, Carnahan is so good, he’s able to distract from some of the script’s problems through his great writing. I mean we don’t get our first lead in the investigation until around page 70 or 80, when Paul’s ring shows up on a man in the emergency room. Before that, we’re casually showing Paul’s “Taxi Driver-like” transformation. He goes to the shooting range. He buys guns. He roams the streets.

We’re a little ahead of Paul here. We know what he’s up to, and you can’t help but get a little impatient. I would’ve liked for a little more variety in this second act and a few twists and turns as well. Anything to throw us off the trail. Then again, maybe this is an early 140 page draft and Carnahan plans to cut it down, in which case we won’t be waiting around as long for things to happen.

In addition to what I mention in the WYSR below, Carnahan taught me a couple of things with this script. To be unflinching. Go to darker or “further out” places than maybe you feel comfortable with. You can always rein it back in if you’ve gone too far. – And experiment with the medium a little more. He really tries some cool things with the format, particularly during the rape scene that, I thought, added more to it than a standard approach would’ve.

Death Wish is a hard script to read because Carnahan takes you as far down that alley as he can. It’s got some great writing, some great dialogue, and some memorable characters. It’s just too chunky in the middle right now. Assuming he’s since found a way to speed that portion up, this could be really good.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Carnahan always has a PURPOSE when he writes a scene. He knows what each character wants out of the scene, and he knows what HE wants to do with the scene. So the scenes always have PURPOSE. Contrast this with Tusk, which I was talking about yesterday. Kevin Smith goes at his scenes in the exact opposite way. He just sees where his characters will take him. This is why his scenes often drift aimlessly and go on for way too long. – Look, it’s fine to feel out scenes when you’re writing a first draft. It’s a great way to find your characters’ voices and to discover some interesting plot threads. But as you near your final draft, all your scenes should have purpose – they should have a clear point going into them so that they DRIVE the scene forward.

Horror has a certain power over me that I can’t explain. So primal is my need to be scared that I will watch every studio horror film released. It’s why I went to see Annabelle. It’s why I’m going to see Ouija this weekend. Do I think Ouija is going to be a good film? Hmmm. Will Renee Zellweger ever look like herself again? The answer to both questions is, of course, no. But if I can get just a couple of scares out of the viewing, I’ll be happy.

Having said that, deep down, I’m always hoping that this is going to be “the one,” that rare horror movie that doesn’t just titillate, but resonates. After reading the awesome “February” yesterday, I asked myself, “What is it that makes a good horror script?” How do you achieve that rare feat of going beyond the scares and giving the reader a fully-rounded experience, like how one feels after watching “The Exorcist” or “The Sixth Sense?”

I don’t know. But looking back at the horror films/shows/scripts I’ve liked recently (The Walking Dead, Mama, Honeymoon) and comparing them to the ones I hated (Annabelle, Oculus), there do seem to be some consistent threads in each. So I wanted to highlight those so you horror writers can give this thing a proper go. This shouldn’t be considered a final list. I’m far from a horror aficionado. But these should give you a baseline on how to get horror right.

Go in with higher expectations – One of the problems plaguing horror is it’s the genre with the lowest expectations. People see horror mostly as a vehicle to throw cheap scares and gore at the screen. Writers pick up on this and, as a result, set the bar low for themselves. Once you’ve done this, you’ve basically guaranteed your script will be bad. Treat horror just like you would a drama. Aim high and deep. I don’t care if you’re “only” writing a slasher movie. Try to make it the best slasher movie ever. There are few things as depressing as reading a lazily written horror script.

Deep characters – Remember this simple rule. If we don’t care about the characters (love’em or hate’em), we won’t care what happens when they’re put in danger. You cannot illicit fear from apathy. The reader must have a strong feeling about the characters one way or the other. So before you write your horror script, spend a LOT of time building your characters. Figure out their backstories, their fears, their flaws, their broken relationships. What is it they need to overcome in this journey? The more you build into your character, the more likely we’ll care about them.

Tie the scares to the characters – The horror and the scares in your screenplay should not be mutually exclusive. They should be designed around one another. In other words, try to connect your character’s fear to the horror at hand. In Mama, the step-mother’s fear is love, is getting close to these children. The scares in the movie then, surround this ghost mother who wants the girls back. The step-mother will have to learn to love the girls in order to save them. The closer you can connect the scares and the character’s own issues, the more impact the scares will have.

Original scares – Cliché scares are one of the most abused practices in horror writing. And this goes back to the first tip. Expectations need to be higher. If you’ve seen the scare before, DON’T USE IT. Or, at the very least, find a way to update it. One of the things that really annoyed me about Annabelle was the old-timey record player that kept turning on. Give. Me. A break. This is pure laziness. The Walking Dead is really good at spinning old cliches. We’ve all seen the scene where our characters have to pick up supplies at the supermarket but zombies are lurking about. Well, two seasons ago, they had a scene where the ceiling crashed in and all the zombies on the roof dropped down, trapping our heroes. Or this season, they had a scene where they had to get the food in a flooded storage basement, adding a unique challenge (walking in waste-high water) and type of zombie (a “floatie”). It’s never easy to sit down and challenge yourself for hours to come up with something new and original. You feel like you should be writing instead, and that you’re wasting time. But when you put in that extra effort and DO find an original scare or a new spin on an old scare, it makes your script so much better.

Be truthful – Don’t force illogical truths into your story just to get scares. When you do that, you’re being dishonest and bending the rules of reality to fit your plot. Instead, you should always try and be truthful, to offer reality. The more realistic the world you create is, the more we’re going to suspend our disbelief. One of the biggest problems with Annabelle was that the doll was the creepiest fucking doll in the universe. It looked like the picture-perfect version of a what a movie possessed doll would look like (and nothing like the actual doll it was based on). If that was it, I’d say fine. But where you’re being dishonest is having the mother character want it in the first place. Who in their right mind would want a doll like this? “Hey hubby? Can you grab me the creepiest fucking doll you can find for my collection?” Yeah right. There was nothing truthful about this plot point, and if you lie like this to the audience too many times, they call you on your bullshit and check out.

Atmosphere – You saw me talking about this yesterday with “February.” Horror is about atmosphere. It’s never just about walking into a room. It’s about the mood in the room. It’s about what’s creating that mood. Are the heating pipes banging obnoxiously behind the walls? Are there ice crystals forming on the window due to the -12 degree temperatures outside? Is your hero scratching at that annoying rash on his arm that won’t go away? Don’t be afraid to show those dead flakes of skin falling to the ground either. Atmosphere can be your best friend in a horror script when done right.

Loss of control – One of the scariest feelings for most people is a complete loss of control. Prey on this fear. As your story maneuvers through its plot, your characters should have less and less control over the situation. And at some point, they should have no control at all. They should feel completely helpless. Look at movies like The Exorcist, Human Centipede, and the little known Aussie film, The Loved Ones. Our fear is based almost exclusively on the helplessness of the main characters.

Build – Horror movies never seem to work when you jump into the scares right away. They need to be groomed and raised. They need to grow up over the course of the film. In other words, you want to BUILD UP to the scares. Look at Paranormal Activity, one of the most successful horror films of all time. That movie goes about three-quarters of its running time before a genuine scare occurs. Before that, it’s mainly a series of small building scares. As a general rule, try to design the first 60-70% of your movie as creepy and the last 30-40% as scary.

The prelude to the scare is often more scary than the scare itself (aka “Milkage”) – A good solid scare is wonderful. But if that’s all there is, you’ve entertained your audience for all of one second. The real key to scaring is chronicling what happens BEFORE the scare. That’s where the gold is, as you can draw the feeling of fear out. As such, you should be designing scares that have a great lead-up, a period of “milkage” if you will. One of my favorite script scares is still in the original draft of The Conjuring, which they ended up cutting. In it, our main character is inside the wall crawlspace, and has found a hole that goes into the basement. There’s a rope coming out of the hole. She starts pulling it. And pulling it. And pulling it. Our imagination is so wrapped up in what’s at the end of that rope, we don’t realize that it’s the prelude to this reveal that’s really scaring us. Of course, a great reveal at the end doesn’t hurt either (in this case, the noose around the witch’s head).

An impending sense of doom – We should feel like bad things are coming for our characters in the future. This should stress us out. We should never feel comfortable in a horror film, like things are going to be okay. We should always feel like it’s going to get worse, that doom is just around the corner.

Plenty of you out there eat, sleep, and breathe horror. And I’m interested to hear your thoughts on my list. Beyond what I’ve noted, what do you think makes a good horror film? Share your tips with the rest of us.

Genre: Procedural

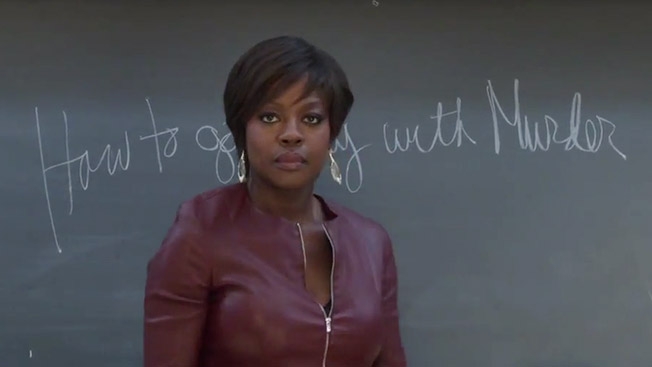

Premise: One of the top lawyers in the country is also a professor who recruits her law students to help her win cases.

About: The new show coming this fall from TV mogul Shonda Rhimes. After going to film school, Rhimes was able to put together a short film in 1998 that starred Jada Pinkett-Smith. She would later sell a spec to New Line, write the Britney Spears film, Crossroads, write the sequel to The Princess Diaries, then a year later, change her life with Grey’s Anatomy. Rhimes is teaming up with longtime collaborator Pete Nowalk, who’s worked with her on Grey’s and Scandal. He wrote the pilot and created the show.

Writer: Pete Nowalk

Details: 63 pages – 12/3/13

When you want to write a hip new unorthodox show about cancer or the apocalypse, go to HBO or AMC. When you want to write a show that everybody in America watches, you go to Shonda Rhimes. This girl has the pulse of America on her fingertips. Whatever the magic TV touch is, she’s got it. And her latest, How to Get Away With Murder, is the most buzzed about network show coming this year.

To be honest, I have no interest in network shows. There’s a reason they’ve been shut out of the Emmys. While everyone else is taking chances, they’re playing it as safe as the medium will allow it. Ongoing storylines are sacrificed in favor of a simplistic procedural style that allows easy entry to latecomers. This results in a nice quick fix after a long day of work, but few rewards for longtime viewers, the ones who keep the show on the map.

But I’ll tell you this. These shows pay their writers well. And since not everyone can spearhead the next Breaking Bad, you writers looking to make a career at this shouldn’t mark these network shows off your list. Especially if you get a shot at working with one of the best network prime-timers in the business, Shonda Rhimes.

How To Get Away With Murder starts the way you’d hope a show with that title would start. Preppy Michaela, sexy Patrick, Boyish Wes, and bookish Laurel, all grad students at Middleton University, each have blood on their hands. No, LITERALLY. They actually have blood on their hands. The four have just murdered someone. But the snippets of dialogue they exchange aren’t telling us the whole story. All we can see is that they’re scared and they don’t agree on what to do next.

Flashback to 4 months ago, when the four enter one of the most prestigious legal classes in the country, Criminal 101, or how their sociopath but highly successful law professor, Annalise DeWitt puts it: “How to Get Away With Murder.”

Annalise, like a lot of Rhimes’s characters, has many dimensions. She’s strong. She’s smart. She’s demanding. She’s calm. She’s cunning. She’s evil. And she has secrets. Oh, does she have secrets. Annalise tells the class that they’re going to be helping her in her latest case, where a woman, Gina, is accused of trying to murder her boss by exchanging his medication with one she knew he was allergic to.

Annalise makes a little game of it. Whoever does the most to help win the case gets her coveted “immunity idol trophy,” (which, of course, later becomes the murder weapon for our students). The trophy allows you to get out of exams and assignments. And it’s implied that whoever gets it first will be the one Annalise mentors this semester.

Each student has their own ideas on how to defend Gina, but Wes is the one we center on most. Wes catches Annalise in bed with someone, gasp, other than her husband, so she places him on Team Annalise to… what? Keep him quiet? Or because he’s actually good? As is usually the case with Annalise, we don’t know.

Over the course of the trial, Wes will learn that Annalise refuses to lose. It doesn’t matter if she has to take down the people she’s closest to. She will ruin lives and threaten others. All in the name of being the best lawyer in the country. The question is, does Wes want to be a part of that, a team that sacrifices their morals to be the best. Or does he want to live that quiet easy legal life without any headaches, the exact life Annalise despises so much? We’ll have to watch to find out.

Man, let me say this. This Nowalk guy knows how to freaking pack a story. There was a TON of stuff going on in How to Get Away With Murder. But not in that bad clumsy way you see in so many amateur scripts. Every piece of information is cleverly set up to be paid off later. Oh, that man Wes accidentally caught Annalise banging? That wasn’t just for shock value. That comes back in the trial.

That’s the thing with “Murder.” Everything is a setup. Which means almost every scene in the second half has a payoff. I really don’t know where to start here because there’s so much good. I mean yeah, it’s cheesy entertainment. There’s nothing that heavy here. Even death is protected by that ABC “everything’s going to be okay” sheen. But it’s all so damn entertaining.

Every character here is memorable. And that doesn’t mean they’re all complex. But Nowalk is really good at setting up who the characters are. He does this cleverly right away actually, by placing Patrick, Michaela, Wes, and Laurel in a messy situation.

If you’ve read Scriptshadow, you know this is one of the best ways to show the reader who your characters are. Put them all in a bad situation, then watch how they react. Patrick is freaking out, Wes is calm, Micaheala can’t make a decision, Laurel is defiant. As with any bad situation, each character will react differently. And it’s that difference that allows us to see who they are.

From there, Nowalk creates a ton of mystery boxes so that we’ve got multiple things to wonder about. It’s like hedging your bets as a writer. If they don’t like this mystery box, they’ll like that one. If not that one, we’ll create another. There are four main ones – who the hell did these students murder and why? There’s a missing girl in the flashback storyline (which I didn’t even have time to get to). We have the case itself (Did Gina do it?). And we have a mysterious girl who lives across from Wes who gets into arguments every night with the former boyfriend of the girl who’s missing.

Then you have Annalise herself. What a great character. Rhimes and Nowalk are really good at this stuff. Annalise is so complex. She gets mad when you think she should be calm (after you just did well in class), or calm when you think she should be mad (after Wes catches her having sex with another man).

But the best part about this character is that Nowalk and Rhimes aren’t taking the easy way out with her. They’re making her just as bad as she is good. In fact, I’d argue that they haven’t shown us any good yet. She’s cheating on her husband. She (spoiler) throws a friend under the bus to save her client, even though she knows her client is guilty. And she’ll break down on a dime to get you to side with her, only to coldly go back to neutral the second you turn away, showing us it was all an act.

I think the thing that most impressed me though was a scene in the middle of the script. It’s a scene that very easily could’ve been spat onto the page, but Nowalk CRAFTS the scene, turns it into something much better than it could’ve been.

It’s a scene where Annalise tells the class that tomorrow, they’ll each have one minute to pitch their angle on how they’d defend Gina. The handful of students who come up with the best defense strategy, she’ll take to court. I want you to think about how you would write this scene. Stop right now and imagine it in your head.

Here’s how the scene was written. First, Nowalk did something smart. The best scenes are usually set up in some way. So we go back a few scenes to set this scene up. Wes had screwed up in class on the first day. Because of this, Annalise told Wes that he’d be pitching last, after all 80 students. And he wouldn’t be allowed to repeat any of the previous suggestions.

This way, when the scene begins, it has form. Why? Because we know Wes is pitching last. This creates both SUSPENSE and TENSION. Suspense because we’re eagerly anticipating Wes’s turn and what he’s going to say. And tension because as each person pitches, Wes has to cross one more idea off his list. At the very end, someone takes his final idea. And Wes has to come up with something on the fly.

I’ve seen the amateur version of this scene before. Bad writers want to shoot straight to the fun stuff, the jump-cutting between each student as they give their defense ideas. The scene has no form because it doesn’t have anything anchoring it (like Wes). Dare I say that it’s predisposed.

How to Get Away With Murder is harmless entertainment. But it’s as good as you’re going to find harmless entertainment. I’ll be trying to get away with murder this September. You should too.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Going back sometimes allows you to go forward. If you’re struggling to write a scene, see if you can go back a scene or two and SET SOMETHING UP which will allow you to write the scene. That’s what Nowalk did here. By going back and setting up that Wes screwed up, it allowed him to create this class scene where Wes is told he’s going last and can’t repeat anyone, which made the scene way more exciting than had it been written straight-up.

What I learned 2: Create dual-jobs for your hero to discover untapped concepts. One thing I realized here is that typically on television shows, a lawyer is a lawyer. That’s all they do. Ditto almost any job. A cop is a cop. A doctor is a doctor. But we live in a world where lots of people have two or more jobs. Under this setup, your characters will have multiple skills and lives. These skills can be combined in unique ways to create untapped show ideas. That’s what happened here. Annalise is a professor and a lawyer. That’s what allowed them to come with this unique premise. Had the writers been thinking too linearly, the way everyone thinks, they would never have stumbled across this unique premise.

(Anyone got a caption for this photo?)

(Anyone got a caption for this photo?)

Hot dogs on the grill. Fireworks. Michael Bay. Scriptshadow Newsletter (it’s in your mailbox. Did you check your spam?). It’s the Fourth of July. Which means there’s no Scriptshadow post. But in true Scriptshadow fashion, I’m still leaving you a screenwriting tip. Try to write “crossover characters.” These are secondary characters who are part of more than one storyline. So instead of giving your hero a friend he pals around with at the bar and another friend he jokes around with at work, make the friend at the bar ALSO the friend at work. Make him cross over. I can’t begin to emphasize how much cleaner your scripts will be once you master this practice. Want 500 more screenwriting tips? Grab the Scriptshadow Screenwriting Book, which is only $4.99 at Amazon. That’s less than the cost of a pack of cherry bombs. Plus 3% of each sale goes towards defending America. That’s not true, actually. But I want it to be.