Search Results for: F word

Can two of the hottest new names in film bring life to the overexposed city of Boston? Let’s find out!

Genre: Crime Thriller

Premise: A gun deal in Boston (1978) between the Irish and some local Bostonians goes horribly awry.

About: We’ve got a live one here folks. Everyone’s been telling me that this Ben Wheatley guy is the oak tree’s knees. I’ve been informed I HAVE to see his breakout movie, Kill List, a dark flick about a hitman. And that his upcoming High Rise, starring Tom Hiddleston (Avengers), is gaining a lot of heat as well. Free Fire stars Brie Larson, Armie Hammer, Cillian Murphy and Sharlto Copley. It finished production recently and is currently in post. Expect it in 2016.

Writer: Ben Wheatley

Details: 96 pages – unknown draft

I didn’t know who Ben Wheatley was until last week, when he started popping up on a bunch of web sites and people started e-mailing me that he was the best up-and-coming director since Tarantino. I knew Brie Larson of course. But after Room, she went into that upper stratosphere of actresses I will check out anything they’re in from now on. That girl’s going to win the Oscar.

So when I heard these two were doing a movie together, I just about flipped. Until I saw what movie it was: Free Fall. FREE FALL??? That vapid glorified beat sheet about a girl who climbs a mountain with her dad?? Nooooooooooo!!!

I was so depressed. Until I looked a little closer and saw that the project was actually titled Free FIRE. “Fire.” Not “Fall.” Oh, thank god. I can’t tell you how happy that made me. Time to find out if one of the buzziest projects in the industry is worthy all the hype…

It’s 1978. It’s Boston. Back in Ireland, the IRA is terrorizing the country. Frank and his underling, Chris, are a couple of Irishman who need guns to help fight that war. But this isn’t modern times where you can buy a snazzletooth L14 doppleslicer on Amazon and then 3-D print it four minutes later. They didn’t even have the internet back then. Which meant people had to buy weapons the old fashioned way – in sketchy warehouses in the bad parts of town.

Which is where Chris and Frank are. Accompanying them is Justine, a Swede who’s brokered this deal. Whereas everyone else is rough around the edges, Justine wears an expensive suit and looks as clean as a brand new 1978 Cadillac. Hell, she might even resemble the 1979 model.

On the flip side, they’ve got Steveo. No, not the half-retarded jackass from Jack-Ass, but he might as well be. Steveo’s already high on heroin when he shows up and sports a shiner from a mysterious run-in last night. Frank did NOT want Steveo on the team but he didn’t have a choice. They needed a man. Their usual guy pulled out. Call goes out to Reject #1.

The group heads into the warehouse. Leading the dealer side is a U.S. military man named Ord. He’s the kind of guy you want leading you down the trenches in Nam. His professionalism is downright intimidating, and he assures Frank that everything’s going to go smoothly and they’ll all be home with their children within the hour.

Wait a minute, Frank thinks. Since when were things NOT going to go smoothly? Why would they have thought otherwise? Oh yeah, we’re dealing with guns. LOTS OF GUNS. And when you deal with lots of guns, there’s always the possibility that something will go wrong. And something does go wrong. Frank was told that they’d be buying M-16s. But Ord has AR-18s, an inferior gun, instead. Frank’s pissed but they need these guns badly.

Meanwhile, one of Ord’s men, Harry, keeps eyeing a twitchy Steveo. There’s something familiar about this nitwit. The high-as-a-kite Steveo notices the attention and tries to play it cool, until Harry realizes where he knows him from. Steveo was part of a gang that bruised up his peeps last night, one of whom was Harry’s 17 year-old cousin. Harry starts chirping at Steveo, who swears he doesn’t know what Harry’s talking about, but the exchange gets louder and louder and, oh yeah, don’t forget there are over 200 guns sitting around…

I think you know which direction this safety switch is being flipped. Everyone scatters and a gunfight ensues. Like, the gunfight of all gunfights. To make matters worse, a third party starts firing AT BOTH SIDES from deeper inside the warehouse.

The. Fuck??? Who are they??? Nobody knows. But when everyone gets to cover and half of them are dead or dying, the sides will have to negotiate a way out of this mess, a task that no one seems up to. This gives us the distinct feeling that nobody’s getting out of here alive.

Let’s begin with Wheatley’s writing style, shall we? This might be the first professional screenplay I’ve read that was written on an iPhone. Contractions, capitalization, and punctuation (I’m talking essential punctuation, like periods) are scuttled in favor of text-like dialogue exchanges. Those of you who’ve gotten to know “Name” in the comments section and his infatuation with centering titles, would probably watch his head explode if he read this.

Now you may think I’d rip a script to shreds for this because that’s what I’d do if this were an amateur. So I’ve got to be fair, right? Well, I also know that this is a writer-director. And that means he’s not writing his script to get through the 15 levels of Hollywood “yeses” required before the script can be sent to a director. HE IS THE DIRECTOR. For that reason, fair or not, he doesn’t have to play by the rules. It’s the same reason Quentin Tarantino can make 800 spelling mistakes. His movie is already guaranteed 50 million for production the second he types the final period.

And hey, to be honest, I kind of dug this writing style. No, I don’t want you to adopt it. But dialogue is supposed to read quickly. And this text-approach without big letters and contractions and punctuation to muck up the words read super-fast. Since this was a dialogue-centric script, and since that style worked, I was liking what I was reading.

And in the end, all that matters is that the story works. And this story works. Not only that, but it’s unlike any script I’ve ever read. It’d be like if Martin Scorsese wrote a contained thriller. Ever fathom that? That’s exactly what you get here.

The script opens with a build. We’re building towards something important, and as each page goes by, the implication of just how dangerous this deal is grows. You know how I tell you guys to utilize an IMPENDING SENSE OF DOOM in your horror scripts? Imply that something bad is coming, then milk the suspense up until the point where you release the doom? Well, you can do that in any genre, and Wheatley does it to perfection here.

We get inside this warehouse and we can just tell something’s going to go wrong. Everybody’s so careful, but they’ve all got itchy trigger fingers. And itchy trigger fingers during a gun deal are liable to start scratching at some point. Bullet-scratching that is.

Remember back when I reviewed Jack Reacher? I told you that a scene that ALWAYS works, is to put two characters together who don’t quite know each other, and have one character cleaning or fixing or tending to a gun. The tension from that gun being in the middle of those characters brings the conversation alive. Because the audience knows that the potential for danger is just a flick of the wrist away. Well, Ben Wheatley has taken that concept and multiplied it by 1000. It isn’t just one small gun between our characters. It’s a couple hundred big guns.

With that said, when the giant gun fight finally begins (around page 40) and ends (around page 60), all of that built up tension is gone. We feel a bit like we’re laying around after sex. Sure, there’s the chance that the two of you could go again. But it’s not going to be as good as the first time, which was the release of an entire night of built-up sexual tension.

Indeed, these guys are talking back and forth with each other, trying to negotiate a solution, and we’re sort of like, “None of this is going to be as good as that earlier gun-fight.” What they needed to do was play up the mysterious third party A LOT MORE. Had they done that (and no, I don’t know why I’m referring to Wheatley as “they” now either), they might have had something to fill this new drama-free second-act void they’d created.

But the script excels in that it isn’t like anything else out there. Wheatley takes what’s typically a mid-script set-piece or a third-act climax and builds an entire movie around it. That’s forward-thinking and implies a storyteller who doesn’t see the world like the rest of us. If you can see the world differently from everyone else yet still see it in a marketable way, Hollywood won’t just let you through their doors, they’ll personally find you and drag you through them.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I have a plea for all future writers of crime screenplays. Please please PLEASE do not use Russians. Using Russians as bad guys is so beyond cliché at this point, it’s embarrassing. It was so refreshing to read a crime script without Russians for once. And yes, I get that it was set in 1978 where you wouldn’t see Russians, but still. Use anybody but Russians, or any Eastern European countries for that matter. You’re more imaginative than that!

What I learned 2: RELEASE THE DOOM! How do you build a story? Find a point in your screenplay where doom is unleashed (aka – a huge gunfight). Then retrofit your story to slowly build up until that moment occurs. As long as we feel like things are building, we’re going to stick around until you hit us with the doom.

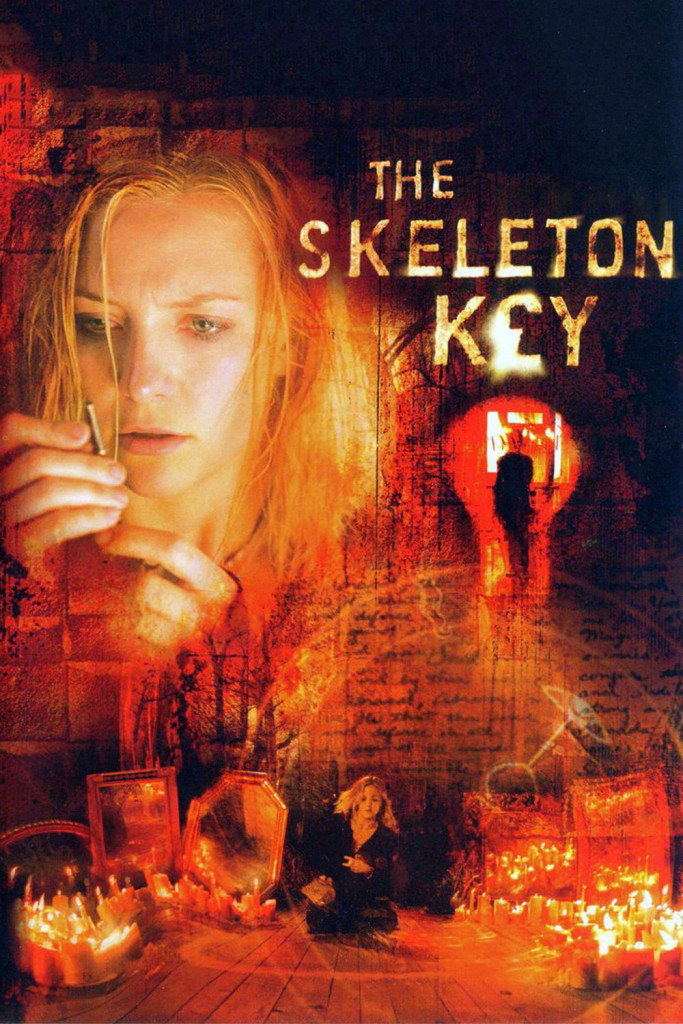

Welcome to a new weekly feature here at Scriptshadow. Now there’s no guarantee this is going to catch on. You may demand your money back in favor of extra Amateur Offerings voting. But I thought it’d be fun if, every week, either myself, or one of you, pitch an obscure, unknown, cult, or under-appreciated movie, offer it up to the readers as a recommendation, and then we can all discuss the screenwriting merits of it. I thought I’d start the first couple of weeks, and from there on out, readers can submit their suggestions to carsonreeves1@gmail.com (I know Poe will have a few!). If I read a compelling pitch, I’ll make that the “obscure movie of the week.” Just give me the movie title and then 300 words on why you think people should give it a watch.

We’re going to start with a ten year old movie that I believe is one of the most overlooked horror films of the new millennium. When it came out, I don’t think people realized how deep it was. They tagged it as one of the many “Sixth Sense” and “Ring” knock-offs that were coming out at the time. But there’s so much more going on here.

I think that’s where the movie got screwed. Because if you watch it passively, it does feel a little dumb. But if you pay attention – and I mean REALLY pay attention – you will experience one of the most fucked up and horrifying twists you’ve ever witnessed. It’s really disturbing. And here’s the thing. I don’t think half the people who watched this movie got the twist. I still remember Roger Ebert reviewing the film on his show and bringing up “nonsensical” things that indicated he didn’t understand said twist either. So go check this out (sorry, you’ll have to find it yourself) and discuss in the comments. Also feel free to down-vote this new feature if you’re not a fan. Enjoy!

As I’m sure all of you are running off to watch the new Bond film this weekend, you’ll have to tell me if my script review was correct or not. If you’re like me and staying farrrrr away from that Octapussy, here are a few amateur scripts to read and vote on. We’ve got selections that contain something for everyone: magic, the devil, poems, a writer even drops the gauntlet! So start the downloading and the evaluating. Oh, and PLEASE open your comment with your vote! And if you can, let us know how far you read and why you stopped.

And if you want to submit your script for future Offerings, e-mail carsonreeves3@gmail.com with your title, genre, logline, why we should read, and a PDF of the script itself! Let’s find the next Unlawful, which finished on this year’s Blood List!

Title: Otherside, INC.

Genre: Action/Adventure Comedy

Logline: While working as henchmen at a magical security firm, a young witch and her rakshas friend must overcome interspecies politics, supernatural bureaucracy and a handsome jewel thief to stop a product-launch from snowballing into the apocalypse.

Why You Should Read: Through most of Thor: The Dark World, Supriya believed she was watching an anti-imperialism tale that would end in Thor returning the Dark Elves’ sacred magical relic, restoring balance to the world, and learning why appropriating another culture’s artifacts is wrong. After Ibba finished laughing at her, they decided Supriya’s misconception would make a great film. Otherside, INC. is the result. Combining their love of genre adventure stories with their day jobs as marketing hench-women they created a supernatural satire for fans of superhero blockbusters and office comedies alike.

Title: Dan Demonic

Genre: Adventure/Comedy? (writer did not say)

Logline: Years after the Devil himself has conquered Earth, an ornery demon and his equally belligerent sidekick are mistaken for the saviours of mankind. Together, they must rediscover their own humanity in order to save the world.

Why You Should Read: Writers like Max Landis have long lamented the death of non-IP in Hollywood- especially in an era when franchises are king. In writing Dan Demonic, I set out to not only captivate an audience with a thoroughly original and engrossing story, but to create a world that could support multiple films within the same universe. Things were tried and rules were broken, but Dan Demonic is a script I’m proud of for its unerring commitment to craziness. If stories about demon strippers, undead Nobel Prize winners and 50-storey flying dogs don’t appeal to you, stay away from this one. However, I hope that those who do give this Guardians of the Galaxy-meets-Beetlejuice hybrid a shot come away from it entertained and enthralled. That would be the biggest compliment of all.

Title: The Iliad

Genre: War epic / Sword and sandal

Logline: A gritty adaptation of Homer’s epic, following the exploits of the (anti)heroes and gods who fought in the last days of the legendary Trojan War.

Why You Should Read: Longtime lurker, never-time poster. Hopefully a few people have read / are familiar with the ILIAD and its impossible to adapt content. I appreciate any (except the bad) feedback. Thank you.

Title: American Funeral

Genre: Horror

Logline: “An agoraphobic 12 year old who suspects his mother and siblings of murder also suspects that he’s gonna be their next victim unless he does something about it, fast.”

Why You Should Read: I noticed that on Monday you said that ELI is the “last” horror script that you were going to be reviewing (I presume for the year) but before you do that I was hoping to take it on in “The Gauntlet” with my horror script AMERICAN FUNERAL. From your review of ELI, I noticed that it has some similarities with AMERICAN FUNERAL. Both scripts have preteen boys as the protagonists. Both boys have “disabilities” that prevent them from leaving their “homes.” And both boys discover some shocking truths about themselves and their families.

However, one of the scripts here is a pro script that made it to the top of the Blood List while the other script is by an unknown writer and it’s still trying to worm it’s way on to the Amateur Friday list. But I have faith in my boy Dougie and I believe he can take on little Eli. So, I’m dropping the gauntlet!

Title: S M A R T H O M E

Genre: Drama, Mystery

Logline: While visiting Tokyo on business, JIM STARR gets trapped in a dangerous Smart Home with a mind of its own.

Why You Should Read: Please help me. I’m stuck in this Smart Home and I can’t get out. I don’t know if it’s an iOS system failure or was hacked by a human out for blood? Oh, God. I hope this message goes through, the Wi-Fi fades in and out. On purpose. I’m being cooked alive. HELP ME! Is anyone there? Is anyone reading this? Hello? Did it go through?? Please! The house knows things about me that may or may not be true. I don’t even know anymore…[DISCONNECT].

Genre: Horror

Premise: A company man is tasked with recruiting a rogue board member who’s disappeared while attending a remote “wellness” center in Switzerland.

About: I’ve always liked Gore Verbinski. A lot of people gave him shit after cashing in with the Pirates’ sequels. But before that he did the offbeat “The Weather Man,” the awesome, “The Ring,” and the cool underrated flick, “The Mexican.” He even made one of the most unique animated films ever in Rango. So when he’s not big-budgeting it, I always pay attention. And it looks like Verbinski’s going back to his roots with “Cure for Wellness” (currently in post-production). Verbinski wrote the script with Justin Haythe, who’s probably best known for penning the underrated Dicaprio/Winslet flick, Revolutionary Road. Let’s see what the two have in store for us today.

Writer: Justin Haythe (Story by Justin Haythe and Gore Verbinski)

Details: 118 pages – 2/17/15 draft

One of the hardest things to do in the horror genre is find a concept or location that hasn’t been used before. There are those who will tell you that everything has been done before so you shouldn’t even try. It’s best, according to them, to find a well-worn idea and put a new spin on it.

But I have a theory about writing. I call it “Hard vs. Easy.” Every writer makes a choice to write in either “Easy Mode” or “Hard Mode.” Easy Mode is when you turn off the analytical side of your brain and just write. You are not judgmental of your writing. You don’t go back and wonder if you could’ve done better. Whatever you put on the page is what you put on the page.

I call this “Easy Mode” because it doesn’t take any work. You write what you write and that’s it. “Hard Mode” is the opposite. In “Hard Mode,” you ask the tough questions like, “Have I seen this before?” And if you have, you go back to the drawing board and try to come up with a better choice. Hard Mode is hard because it’s not fluid. There’s a lot more stopping, a lot more thinking, a lot more judging. When you do come up with something, you have to rev yourself back up since you haven’t put anything on the page for awhile. Overall, it’s a much more taxing experience.

However, “hard mode” tends to provide better results because you’re nixing the clichés and obvious story choices that plague the majority of scripts out there. Writers who work on hard mode are more likely to find new locations, new ideas, new characters, because they just aren’t satisfied with the status quo. They know how vast their competition is and realize that the only way to compete with them is to challenge every idea they come up with.

A Cure for Wellness takes us to a place we’ve never been to before in a horror movie. That’s a “hard mode” choice. Sure, Verbinski and Haythe could’ve placed us in yet another mental institution. But we’ve seen that before. We’ve bought that t-shirt. Is it hard to nix that and spend a couple of weeks trying to come up with a location we HAVEN’T been to? Of course it is. But in the end it pays off because you’re giving the audience something ORIGINAL.

A Cure For Wellness introduces us to Castorp, a rising star at an unnamed company. Castor is the embodiment of the American upper-class male. He works 18 hours a day and is driven only by making more money and gaining more status than his fellow man. Castorp has no family, no friends, and defines his worth simply by how much business he can bring in for the company.

Right now, business is good. Castorp has been recognized by the board for his outstanding work. And they want to reward him. But first, they have a task for him. One of the board members, Roland Pembroke, went off to a “wellness” center in Switzerland and hasn’t come back. A big merger is coming up and Pembroke needs to sign off on a few things before the merger can happen.

Castorp isn’t happy, but anything that gets him further up the company ladder is a price he’s willing to pay. So off he goes to this remote wellness center, which happens to be in the mountains of Switzerland, one of the most beautiful places in the world.

Once there, Castorp realizes there’s something “off” about this place. While it’s state-of-the-art and all of the wellness clients seem happy, there’s a mysterious air about it all. Everyone always seems to be going off to their next “treatment,” and when they come back, there’s something a little less “there” about them. Oh Castorp, if you only knew how much worse it was going to get.

Castorp requests to see Pembroke at the manager’s office, but it’s past visiting hours, which means Castorp will need to wait until tomorrow. Castorp, personifying the impatient American businessman, demands to see Pembroke now. He’s eventually visited by the wellness center’s founder, Henrich Volmer. Volmer is a calming man, and assures Castorp that he’ll be able to see Pembroke soon.

A frustrated Castorp decides to head back into town while he waits, but ends up getting in a car accident. He wakes up three days later inside of, you guessed it, the wellness center, where Volmer informs him that his body is all out of whack. Volmer encourages Castorp to participate in his program, which, as you can imagine, takes Castorp down a rabbit hole he may never climb back up from.

Cure for Wellness invokes movies like The Wicker Man, The Shining, and Shutter Island, but manages to be something in and of itself. Its best asset is its irony. Here we have the world’s topmost “wellness” center, and yet as the story goes on, its clear that its patients are descending into an unrecoverable sickness.

As I pointed out in the beginning, Verbinski and Haythe committed to writing this on hard mode, allowing it to feel quite different from movies with similar setups. One of the creepiest (and more original) choices was the design behind the wellness “cure” for its patients, which was based around hydrotherapy. All of the treatments were designed around water.

You were placed in water, water was infused in you, you were asked to drink a certain water. And so there are a ton of creepy scenes that involve the innocuous fluid. One of my favorites was when Castorp was placed in a water tank not unlike the one Luke is placed in after getting injured in Empire Strikes Back. The techs responsible for him sneak off and engage in a weird sex game. In the meantime, two black eels appear inside the tank and Castorp starts freaking out, accidentally destroying the breathing apparatus, resulting in him losing consciousness, all while the techs are off in the other room, enjoying themselves.

Water tank therapy. Black eels. Tech operators engaging in freaky sex games. Can’t say I’ve ever seen THAT in a movie before. And that, my friends, is how you write on hard mode.

The only thing that worried me while I was reading Cure for Wellness was that it was going to be a “smoke and mirrors” screenplay. What’s that, you ask? “Smoke and mirrors” screenplays – which I see a lot of in the horror genre – are when the writer’s story is driven by a series of red herrings, twists, and half-baked mythology.

They’re essentially one giant sleight-of-hand, a desperate hope that you’re looking at the trick rather than what’s really happening. A good script has its mythology, backstory, and storyline figured out ahead of time so that everything comes together and makes sense at the end. Since horror is an inherently sloppy genre, with writers more focused on scares than story, you see a lot of smoke and mirrors. God forbid you actually do the hard work and make it all make sense.

There are people who feel that Shutter Island was a smoke and mirrors screenplay. There are people who think It Follows was a smoke and mirrors screenplay.

It’s particularly easy to go the smoke and mirrors route when you’re writing one of these “main character is going crazy… or is he???” scripts. The rationale is that because he doesn’t even know if he’s going crazy, we can be unclear about everything, leaving it “up to the reader” to decide what’s real or not. The problem is, when you leave EVERYTHING up to the reader, you prove that you haven’t figured anything out for yourself. Leaving your script feeling lazy and uninspired.

But I’m getting off-track. Cure for Wellness had so many weird things going on that I didn’t think it could bring itself back from the edge. However, the deep and rich backstory about the wellness org’s origins (which dated back 200 years), as well as the reveal of what Volmer did to all his patients –indeed came together in a satisfying way.

I get the feeling that this will be an even better movie than it is a script. It’s got a bit of a “blueprint” feel to it as opposed to a standalone script feel (like yesterday’s screenplay). I’m betting the trailer is going to look amazing. Good to see Verbinski recovering from Lone Ranger.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the things that drives me nuts when reading a script is when the writer preps us for the setting AND THEN FOLLOWS THAT BY GIVING US THE SETTING. Just give us the setting! Screenwriting is about conveying as much as possible in as few words as possible. Telling us you’re about to say something before you say it is a waste of time. Here’s an example from Cure For Wellness: “The Mercedes moves through an idyllic setting: rolling green lawns, terraced gardens where PATIENTS play shuttlecock, shuffle board, lawn boules. Others walk along well-trimmed pathways, through gardens with bountiful flowers.” The first part of that description is superfluous. We should grasp the “idyllic setting” when you describe the “rolling green lawns, terraced gardens, etc.” You don’t need to first tell us it’s an “idyllic setting.” I should point out that this is a personal preference thing. There is no “right” way to write. But writers who follow this rule tend to have smoother easier-to-read scripts.

Genre: Horror

Premise: (from IMDB) An American nanny is shocked that her new English family’s boy is actually a life-sized doll. After violating a list of strict rules, disturbing events make her believe that the doll is really alive.

About: In a Dark Place was retitled “The Inhabitant” which has subsequently been retitled “The Boy,” and it already has one of the creepiest trailers I’ve seen all year. It stars Lauren Cohan, who Walking Dead fans will recognize as Maggie Greene. The script is written by Stacey Menear, who wrote one of my favorite scripts (it’s over to the right in my Top 25) five years ago. This is his first produced credit. The film hits theaters in January.

Writer: Stacey Menear

Details: 115 pages

Halloween Week continues here on Scriptshadow and today makes me soooooo happy! Stacey Menear, whose script, Mixtape, I reviewed five years ago and who gave an interview to us around that time, has finally broken through with his first produced credit! It kills me when super-talented writers give up amongst the hard knox of Hollywood and I’m so happy to see that Stacey pushed through the tough times and got a film made.

It’s important to remember that one of the most underrated components to making it in this business is sticking it out. Getting better and better with each draft, meeting more and more people who become fans of your work, until finally, one day, talent, skill, experience, and all that networking come together for a film opportunity. Stick with it folks. Don’t give up before it all comes together for you!

20-something Gerti Evans is running from something. Why else would you leave your country to come be a nanny for people you’ve never met? As we’ll find out later, Gerti just got out of an abusive relationship with some crazy psycho and moving halfway across the world was the only way to escape him.

But Gerti is about to learn that she hopped out of the oven and into the frying pan (or however the saying goes). She arrives at a mysterious mansion in the English countryside and is introduced to the Heelshires, an older couple with a son. Well, sort of a son. The Heelshires, you see, kind of maybe possibly take care of a porcelain male doll who they believe is their boy. His name is Brahms.

Gertie assumes this has to be a joke, but quickly realizes that the Heelshires are anything but jokers. They go on to explain that taking care of Brahms requires following a strict set of rules that involves never leaving him alone, giving him a bath, reading to him, playing music really loud for him.

As soon as Mrs. Heelshire determines Gertie can handle the job, she and the hubby head out for a three-month vacation, leaving Gertie all alone. In this giant house. With a doll. Who they believe is a real boy. Yeah, cue the Exorcist soundtrack.

At first Gertie treats this situation like you’d expect it to be treated. She throws a blanket over the creepy doll and goes about her day. It helps that the cute local grocery boy (or man), Malcom, comes by every once in awhile to deliver some food. And periodic calls with her sister back home, which include updates about her evil ex-boyfriend, Cole, help pass the time.

But then strange things start to happen. Gertie’s clothes are moved. Brahm isn’t always where she left him. She even finds her favorite meal made for her in the dining room one evening. Could it be a joke? Malcom maybe? Eventually, Gertie finds that following the rules laid out by the Heelshires stop these mysterious events. And before Gertie knows it, she’s treating Brahms, gasp, like a real boy. Might Gertie be falling into the same trap as the Heelshires? Or is there some real otherworldly shit going on here?

Uh, this script was fucking awesome. I was thoroughly creeped out. But not just that. Stacey has proven once again why he’s such an awesome screenwriter. There is so much here to celebrate, starting with the structure.

I’ve read tons of these scripts before. And all of them work for exactly one act. The setup . Because these scripts are easy to set up. You have a creepy doll. You have the main character. We know that that doll is going to do creepy shit later. So we want to read on.

But they always fall apart once they hit the second act because instead of the writer actually building a story, they try to fill up space between cliché doll-movie scares. The doll not being in the room they left them in. Some old record player playing old music. Who turned it on?? The sound of laughing or crying in the other room but when our hero goes to check the sound, it stops.

The thing is, In a Dark Place does include some of these tropes, but because it’s also building a story, they work. That’s what screenwriters forget. A trope or cliché by itself is empty. But if it’s something that’s carefully and organically worked up towards via good storytelling, it will kill.

So here, Stacey makes a couple of smart decisions that ensure the script extends past the first act. First, there’s Cole, the evil ex-boyfriend. His presence lingers throughout the script, conveyed mainly through Gerti’s phone conversations with her sister. We know this guy is going to show up at some point, and that leaves a LINE OF SUSPENSE open for some later dramatic shenanigans.

We also have Malcom, who serves as our love interest, and also as our gateway into the Heelshires’ past. In that sense, he pulls double-duty. We like this guy and we want Gertie to move past this terrible relationship she got out of, so we’re rooting for the two to get together. And also, Malcom is nervous about talking about the Heelshires’ past, so we get these sporadic spooky tidbits about their history, including how they got to this point with Brahms.

This leads us, of course, to the mystery of Brahms himself. Who was the real Brahms? How did he die? What are these rumors about him doing something horrible to a little girl? About a fire? How is he able to move? Is his soul really trapped inside this doll? There are so many questions when it comes to Brahms that I couldn’t wait to turn the pages to find out more. This isn’t fucking Annabelle where the extent of the doll’s history is: “Doll is possessed. The End.” There’s an entire mythology built into this weird doll-thing and it was awesome to keep learning about.

And then there were the story twists. One of my favorites was (spoiler) when we learn that the Heelshires aren’t coming back. That they freaking walked into an ocean to kill themselves. And that they left a will that makes Gertie the owner of Brahms. And then they left a separate letter for Brahms. Which said: “Now you have a new doll to take care of.” As in, yes, Gertie is HIS doll. Not the other way around.

I also loved that Gertie becomes a believer and starts taking care of Brahms as if he’s a real child. In every other doll-horror script I’ve read, from the mid-point on, it’s a series of scares with the doll being in other rooms and making noises and our hero getting more and more freaked out until there’s a final battle with the doll.

Gertie becoming a believer was, in many ways, a thousand times creepier. And by making that unexpected choice, it led to a better ending (spoiler) where Cole shows up, starts calling her crazy for thinking the doll is real, and we set up a situation where Brahms can now defend the girl who’s become his protector. You don’t get that story option if you go the traditional route, which is why I love Stacey’s writing so much.

And then on top of that, Stacey’s just a great word-for-word writer. Here’s him describing Gertie’s driver at the beginning of the script: “He’s an ancient looking guy, more hair coming out of his ears than on his head.” Or Gertie herself: “She’s blonde and pretty in that “Hi, I’ll be your waitress for today” kind of way.” And he just added these technically unnecessary but creepy atmospheric things, like the rat problem in the house, with Gertie being forced to clean up the bloody dead rats from the rat traps every week.

There’s not much more to say. I’m a fan! Check out In a Dark Place out if you can get your hands on it!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is the perfect example of a great writer who struggled to get stuff through the system UNTIL he went with a genre script. The thing is though, he didn’t sell out. He found an idea that allowed him to still utilize his particular brand of writing, his voice. This still feels like a “Stacey Menear” screenplay. So don’t think you have to give up your soul to write a genre piece. Find a marketable genre that allows you to still be you as a writer and that way you can write something and actually have a chance of getting it made/sold.