Search Results for: F word

Genre: Comedy?

Premise: A racist southerner has a split personality that turns him into a devout liberal named Rodeo Rob, who believes he’s from the year 2525.

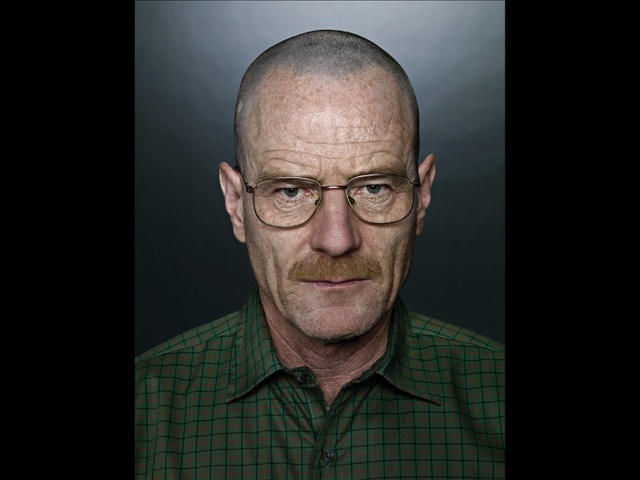

About: Vince Gilligan is the writer of what some consider to be the best television series ever, Breaking Bad. He originally wrote this script back in 1990, and over the years has honed it according to whomever became interested. The closest it got to production was in 2008, when Will Ferrell wanted to star in it. But a director was never found. Says Gilligan: “I don‘t know that the movie will ever get made because at the end of the day, it’s a little bit tricky, because it’s a comedy with the N-word in it.”

Writer: Vince Gilligan

Details: 129 pages! This is the 2008 draft that Will Ferrell was supposed to be in.

Chalk this one up to “What the fuuuuuuuuuhhhhh?”

I don’t know what I was expecting when I opened an early script from Breaking Bad’s Vince Gilligan, but I sure as hell didn’t know it would be this.

On the one hand, this is what you want from a writer – a script that actually takes some chances. But boy, I mean, at what point have you traversed so far off the reservation that the authorities have to come and get you?

Hmm, how to summarize this one. Okay, so there’s this guy named Earl. Earl is in his 40s, is nearly deaf (he wears a hearing aid), is extremely racist, and has a young daughter who’s also deaf. Earl spends his weekends playing a Confederate soldier in Civil War recreations.

Earl and his friends are off to one of these recreations when a black man cuts them off in traffic. This man’s name is Malcom, an academic who’s trying desperately to get into Harvard. At the next stoplight, Earl and his racist buddies, in their Confederate uniforms, get out and OVERTURN Malcom’s car with him in it.

Later, after the recreation, the curmudgeon-y Earl meets up with his ex-wife, Myra, and keeps complaining about this guy she’s been hanging out with, Rob. Later that evening, when the sun goes down, Earl takes his hearing aid off, and his whole demeanor changes. He’s now… Rodeo Rob!

Rodeo Rob, according to Rodeo Rob, is from the future, 2525 to be exact, where he lives on the moon. He’s time travelled back here to, I guess, help humanity. He’s also fallen in love with Myra, and Myra him. Of course, Myra must wake up every morning to Rodeo Rob becoming Earl again, a man she detests.

In the meantime, Malcom, our friend from the overturned car, becomes fascinated with Earl’s split-personality, and figures if he can study him and discover what’s causing the split, maybe it will get him into Harvard.

So Malcom moves next door to Earl (what??) and begins helping him. Of course, Earl wants nothing to do with this, so Malcom has to navigate around that tricky obstacle, mostly conversing with Rodeo Rob. But the ultimate goal is to bring Earl and Rodeo Rob back into one personality. It’s just a matter of which personality that will be.

When trying to separate your writing from everyone else’s writing, tone is one of the few ways you can do it. If you can mix the tone of, say, a comedy, with the stagey feel of the theater, you get Wes Anderson. If you can mix the tone of a documentary with the tone of a sci-fi pic, you get District 9. Put succinctly, mixing tones is a great way to stand out.

But there are some notes that just don’t sound right together. Trying to mix a goofy split-personality comedy, a la “Me, Myself, and Irene” with a serious look at racism? I’m just not sure how you make that work. And when tone is mixed incorrectly, it doesn’t matter what else you do. The script is never going to feel right.

If that analysis is too technical for you, I’ll put it layman’s terms: This script is f*cking weird.

Part of the problem is that Gilligan can never make a restrained choice. He always has to go to level 100 on the scale. For example, Earl’s alternate personality can’t just be the opposite of him (liberal and tolerant), he has to be the opposite of him BUT ALSO BELIEVE HE’S FROM THE YEAR 2525! When Malcom wants to study Earl and his disorder, he can’t do it from his office, he has to move next door to him???

The moment where I knew Gilligan had gone off his rocker, is when he shows us the backstory for what happened to Earl’s young daughter, who also has a hearing problem.

Now I assumed her hearing issue was a result of genetics. Oh no. We find out that a few years back, when Earl was drunk, he dressed up in a KKK sheet to go and scare a group of black people who were swimming in the pool. He brought with him a stick of dynamite to show how serious he was.

What he didn’t know, because he was wasted, was that his daughter was swimming in the pool as well. Well, Earl fell in the pool, the dynamite went off, and since sound travels more prominently through water (or so we’re told), both he and his daughter were turned deaf by the blast. That’s the backstory for them losing their hearing. I kid you not.

Further evidence that Gilligan was smoking the good stuff when he wrote this was a random dream sequence (which included a shark) from the point of view of the daughter. Because why not? The main storyline’s going along. You’ve shown the daughter three times up to this point. Why not hop into her head for a dream sequence? Another strange choice was Malcom being an organ transplant courier. In fact, on the day our Confederates flip his car, he’s carrying two corneas. What??

Three-quarters of the way through the screenplay, Earl’s extremely racist best friend, Booth, burns a cross in his front yard. I mean can we really write a comedy today with the KKK, the N-word, and burning crosses? I suppose the world was a different place back in 1990 when Gilligan first wrote this, but it wasn’t THAT different. I don’t see how someone could look at this and say it was a good idea.

I mean, I commend Gilligan for trying something different, but this feels like one of those early scripts a screenwriter never gives up on that they probably should. We’ve all got those. The nostalgia and bullheadedness keep us coming back to them. I loved Gilligan’s early-days pilot for that cop show he made for CBS. This? This is just… out there dude.

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a reason screenwriting software defines the non-dialogue section of text as “action.” It’s because that’s where you want to write ACTION. “Joe slams his fist down.” “Frank dashes over to his car.” “Carol spins to see the car coming at her.” Too many writers, however, think this section is called “description.” They like to use it for lines like, “Joe’s long hair never looks out of place. It’s like he keeps a personal stylist with him wherever he goes.” “Nearly everything in Frank’s apartment is green. It’s almost forest-like in its appearance.” “Carol crosses the city street, which is populated with early-morning commuters who haven’t had their lattes yet.” Obviously, you’re going to need to describe things in a script. And in small doses, the above examples are fine. It’s when that’s all you write where it becomes a problem. As a general rule, 80% of what you write in the action section should be ACTION, should be THINGS HAPPENING. — The reason Gilligan’s script was 130 pages was because it was deluged with unnecessary description. It made this one of the hardest scripts to get through all year. (note: There are exceptions to this action/description ratio, of course, but it’s almost always true)

Genre: Drama

Premise: An alcoholic who’s been told that his liver is about to give out must move in with the family he’s ignored his entire adult life.

About: “George” finished high up on the 2012 Black List. The writer, Jeff Shakoor, will get his first big-time TV writing credit when Netlfix premieres its show, “Bloodline,” about a rich family with some dark secrets. Shakoor wrote the second episode in the series. You can check out my review of that pilot here.

Writer: Jeff Shakoor

Details: 117 pages

Jon Favreau brought up a good point in that Hollywood Reporter Roundtable I linked to the other day. He said studios always want that likable main character driving the story. As you can imagine, the table bristled at the mention of the word “likable.” Ooh, that evil word. “Likable.”

Favreau pointed out that the very idea of a likable protagonist didn’t fit the hero journey template. In the hero’s journey, a character must have a flaw that they overcome over the course of the story. In most cases, that means starting in an “unlikable” place. The “likable” part only comes once the character transforms.

It’s an age-old problem. And while not every flaw must include an aspect of “likability” (your character’s flaw can be, for example, “not believing in one’s self,” a la Rocky), some of the more interesting flaws, such as selfishness, fall squarely in the path of the adjective.

What writers often forget, however, is the notion of balance. If you’re going to make your hero selfish, and therefore, “unlikable,” you need to establish an equity line of “likability” to balance it out. However, a lot of writers get so angry at the notion of Hollywood telling them they have to make their hero likable, they go in the opposite direction, making their character the embodiment of evil as a “fuck you” to the industry. That seems (to me at least) how we got our lead character in “George.”

60-something George’s alcoholism is so bad, that even when he’s told by his doctor that his liver will cease functioning and he’ll be dead in six months, George still wants a drink. It’s been this way for George’s entire adult life. All he cares about is his next beer, his next shot, his next bottle of Jack.

He figures he’ll spend his last days where he’s most comfortable. The bar. But there’s a problem with that. George is broke. He used to be able to get past that hiccup with his good looks and charm. But George is now in his 60s with that aging alcoholic’s face. Good looks and charm are no longer in his repetoire.

So George is forced to call his ex-wife, Myra, whom he, of course, asks for money. She tells him to fuck off. She’ll give him a place to stay until he dies. But the last thing she’s doing is giving him a stack of cash so he can end his life a couple months early.

Going back home means meeting his now-adult children for, really, the first time, since he was out drinking throughout their entire childhood. The idea is for George to foster some sort of late-life relationships with them, but George has never been the sentimental type. He’s not above asking his grandkids for money so he can secure his next drink.

Of course, George is pulled into his family members’ lives merely by being around (such as when he catches his teenage grandson partaking in a homosexual act) and while he’s far from helpful in these situations, he’ll offer guidance if it involves some level of amusement for himself. Will George finally change before he dies? Will he realize what truly matters in life? Only one way to find out.

I love the whole “unlikable” debate. I think it’s the most fascinating argument in screenwriting. Because Favreau is right. You have to start your hero in a negative place if you want to arc them to a positive place. Nobody arcs from positive to positive. And yet attempts to utilize unlikable characters almost always end in bad screenplays (you guys tend to see all the professional scripts where this works. I see the hundreds of amateur scripts where it doesn’t). It’s hard to root for anybody you hate.

I think there are two types of selfish. There’s fun selfish, a la Bill Murray’s character in “St. Vincent” (spraying water at the neighbors) And then there’s mean selfish, which can probably be equated to a character like Melvin Udall from “As Good As It Gets” (telling people their lives are miserable). Obviously, the “mean selfish” character is a lot harder to pull off. And I’m still not sure how they did it in “As Good As It Gets.”

But they tried it here, and I’m afraid it didn’t work. Shakoor doesn’t even try and build up any “likable equity” with George. George grabs the breasts of his nurses, telling them how hard he would’ve nailed them in his heyday, then goes to the bar, drinks 5 shots in a row, and laughs at the bartender when he tells him he can’t pay for them. It’s pretty brutal.

The first “nice” moment in “George” doesn’t come until page 50 or so, when he helps his grandson, Michael, go find a hooker to see if he’s gay or straight. That’s a long time to wait until the very first nice thing your character does.

I was re-watching Frozen the other day – one might say the “anti-George” – and I realized that if you establish a likability IMMEDIATELY with your characters, you can get away with a lot later on. We establish sisters Anna and Elsa lovingly playing with one another, then harshly broken apart, then pining for one another again, and it pretty much allows them to do whatever they want with Elsa , the Ice Queen” moving forward. We saw how sweet she was capable of being. We pine to see that sweetness again.

It would make sense then, that the opposite would hold true. If you make us dislike your character right away, that feeling is probably going to follow the character throughout the movie.

From a technical standpoint, “George” never quite resonated either. The script is jam-packed with dialogue, which is fine. But 90 percent of it is George insulting people. I’ve said this before. You need to add variety to your dialogue. We all have our patterns, the things we like to do with dialogue. But if you ONLY do that, you’ll tire the reader out. 50 insults in and we were only on page 20 – I needed more variety than that.

So why did this script end up on the Black List? Well, The Black List likes to celebrate scripts that take chances – particularly scripts with unabashedly dark characters (even better if they’re dying – another Black List favorite). Everything from St. Vincent to Cake to Bad Words to The Social Network. If you’ve got a meanie main character, this is where you’re hoping to showcase it.

So by no means am I telling you never to write an unlikable main character. There are plenty of anti-establishment Hollywood folks who will give you the thumbs up for giving them something different. Just keep in mind that it’s always a tough balancing act and if you don’t get it just right, people are going to dismiss it out of hand.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Pay very close attention to what you’re doing with your main character early. Every little thing they do is affecting how we see them. We don’t know this person yet, so their actions are very powerful. They don’t tip, we see them as cheap. They hold the door open for the person behind them, we see them as thoughtful. Your character’s actions are more powerful than you think. Use them wisely.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Psychological Thriller

Premise (from writer): A young widow discovers her husband’s accidental death is the latest in a series of murders-for-profit reaching back more than a decade.

Why You Should Read (from writer): This is based on my published novel. In its review, Mystery Scene magazine described the book as “a story Hitchcock would have approved of.” Exactly what I was striving for.

Writer: John Joseph Moran

Details: 118 pages

Christoph Waltz for Seifer? No-brainer.

Christoph Waltz for Seifer? No-brainer.

Scripts that start out fun always seem to have an advantage over ones that don’t. It takes more effort to get into those moody reads and even when you do, they never quite read as fast as the fun ones. I’m not saying you should never write a drama, of course. But in the competitive world of spec writing where every variable counts, picking up something that moves quickly sure makes things easier.

And that’s the experience I had with The Benefactor. Even at 117 pages, it never really slowed down. But why do I still have a case of the reluctants when thinking about it? Something about it feels… how do I put it? Light. There’s a level of sophistication missing, which left my suspension of disbelief in constant flux. The Benefactor destroyed the Amateur Offerings competition two Saturdays ago so I know a lot of you read it. Maybe, then, you can help me figure out why I felt this way.

When 35 year-old Claire Medina’s husband is hit and killed by a car, it’s bittersweet. On the one hand, he was her husband and father to her daughter. On the other, he was abusive and an altogether terrible person. As much as Claire hates to admit it, there’s a freeing feeling to her husband being out of her life. It’s almost too good to be true.

It turns out that’s exactly the case. A month later, Claire is approached by the sinister Nikolas Seifer, who informs her that he runs a unique business. He finds troubling individuals, individuals that spouses or family members wouldn’t mind dead, and he kills them in what looks to be an unfortunate “accident.” Afterwards, he approaches the spouse and asks for half of their fortune as payment for improving their lives.

Half Claire’s fortune is a lot of money. So Claire tries to find something on Seifer to use against him. But this guy is clever. He’s implicated Claire for the murder of her husband in several ways in case she doesn’t pay up.

Eventually, Claire realizes the best option is to give Seifer the cash and be done with it. So that’s what she does. But 18 months later (yes, you read that right – we have an 18 month time jump), Seifer appears again and tells Claire that to complete the loop, she has to kill someone for Seifer, his next mark.

Claire decides to turn the tables though, encouraging her mark, Fanning, to fake his death in order to take down Seifer. As her and Fanning wait for their plan to take shape, they fall for one another. But just as they believe they’ve cornered Seifer, he turns the tables back on them, and Claire finds herself fighting for her life, as she’s implicated for the murder of Fanning’s wife, a murder she didn’t commit.

This was a wild one. Lots of twists and turns here. The danger with a lot of twists and turns though, is that unless you’re extremely diligent, you’re bound to create some plot holes. There were a good half-a-dozen times here where I stopped and went, “Waaaait a minute. Couldn’t they just…?”

Like Seifer’s system. It’s a clever premise, don’t get me wrong. A hitman predicts that you want your spouse dead and therefore does it for you, only asking for the money afterwards so there’s no way for you to get caught. The catch is, he extorts you for the money.

But why only target “bad” people in this scheme? Since he’s extorting the people for money afterwards either way, can’t he technically do this to anyone, bad or good? What’s the advantage of only targeting bad people? I suppose it’s a little easier to deal with someone who kinda likes the fact that their asshole husband is dead. But nobody’s going to be thrilled when you demand half their fortune for the hit, whether they hated their hubby or not.

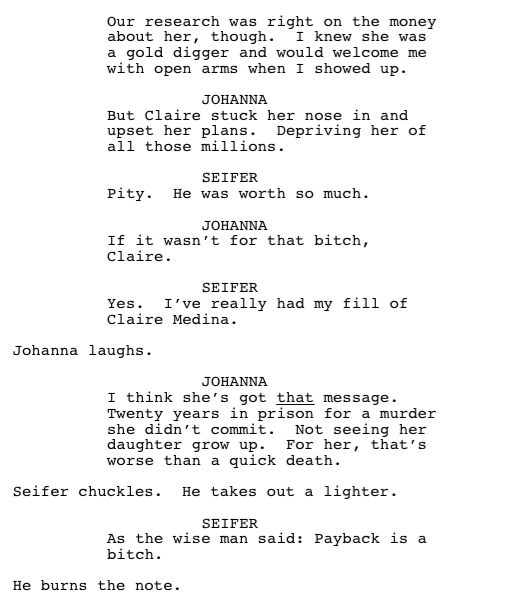

That’s what’s so frustrating about this script. It kept me reading all the way through. I wanted to find out what happened in the end. Yet it was littered with these lazy story pockets that weren’t believable for some reason or another. And again, it went back to a lack of sophistication. Let me show you a snippet of dialogue. Here, Seifer and his cohort, Johanna, are discussing how Fanning’s wife turned on Claire and their plan, allowing Seifer to gain the upper hand against them.

This is so over-the-top and on-the-nose, you can practically hear the sound of Seifer twirling his mustache, with Johanna “MUWHAHAHAING” in the background.

You may also notice the “explainy” nature of the dialogue (“Twenty years in prison for a murder she didn’t commit…”). There is a TON of this throughout the script. “Why can’t we go to the police?” “Because if Character A tells Character B we went to the police then it’ll mean we’re screwed. But if we follow Option C instead, then…”

Explainy dialogue almost always means the writer is using his characters to talk to the reader instead of his characters talking to each other. This is why this dialogue feels stilted and artificial, because it’s being directed at the wrong person. Dialogue must always, first and foremost, sound like two characters talking to each other. As soon as one of them stands up on their “explanation soapbox” to address the reader directly, you’ve pierced the reader’s suspension of disbelief.

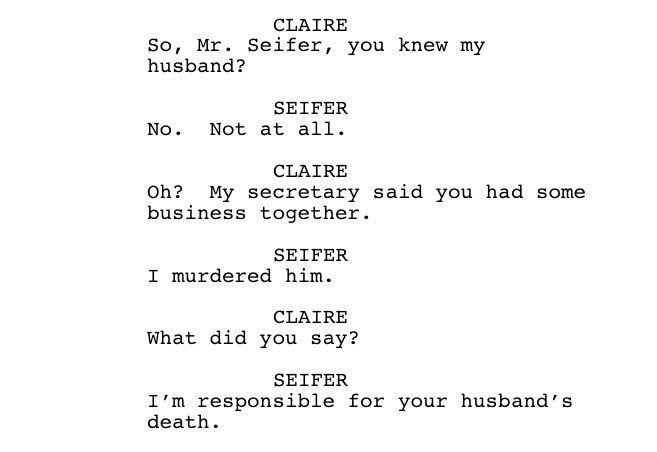

And that problem was persistent throughout much of the screenplay. Too much of the dialogue felt “off” for one reason or another. Take this exchange early in the script. Four weeks after her husband’s death, Claire is sitting in her office when Seifer arrives. Here’s the exchange.

While I don’t think this is terrible dialogue, it rang false (to me, at least). If someone says to you, “I murdered your husband,” are you really going to respond with, “But – My husband died in a traffic accident. I met the woman who drove the vehicle. Mary Boyd.” Someone just told you they are a murderer and you’re responding with a conversational rebuttal?

I could see freaking out. I could see realizing you’re in danger and enacting some sort of stall tactic while you figure out what to do. At the very least, note Claire freezing when she hears these chilling words. But without clarification, it reads like the ho-hum response of someone who’s just been accused of leaving the iron on. It’s emblematic of issues I had with the dialogue throughout.

The other big problem here has to do with time. Remember that unless you’re doing a period piece, you want the time frame for you movie to be as contained as possible. Any big time jumps mean a loss of momentum. But they also mean a lack of planning. It’s indicative of a writer who hasn’t worked hard enough to keep his story moving in one continuous timeline.

I mean the 18 month time jump is nothing short of a momentum assassination. If there’s any way to eliminate it, I’d do it. And then there’s Claire going to jail and the subsequent courtroom trial, which is another huge time jump. You have yourself a thriller here. You don’t want to end up in a boring courtroom drama sequence. Case in point. Imagine if Silence of the Lambs ended in a courtroom case. Do you think it’d still be considered a classic?

As soon As Claire goes to jail, get her out on bond, and have her and Fanning find and confront Seifert. It makes no sense to have your main character sitting in jail while this Fanning character, who we met less than 30 pages ago, searches for our villain.

Speaking of Fanning, I thought for sure he was going to turn out bad. I thought the whole idea behind Seifer’s system was that he targeted evil people. With Claire disrupting the system, I believed the irony would be that she’d pay the price. Fanning would end up doing something horrible to her. But even if you don’t explore that avenue, it seemed weird that all these people Seifer had killed previously were terrible human beings, yet Fanning turned out to be a great guy.

Anyway, I think Moran deserves some props for coming up with a unique premise and an unpredictable story that moves from start to finish. But to get this up to “worth the read” territory or higher, he needs to shore up some of the dialogue issues. I mean this is a “Hitchcock-like” story and I don’t remember a single conversation that included dramatic irony. Watch Psycho and note how nearly every dialogue scene contains dramatic irony (one character is lying to another). Fix that and the excessive time jumps and The Benefactor is going to be the real deal.

Script link: The Benefactor

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me (just missed a ‘worth the read’)

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware of characters being too “explainy” (“Why can’t we go to the police?” “Because a) it means blah blah, b) that would entail blah blah blah, and c) the villain would blah blah us”). Either cut all this explaining out or look for other ways to convey the message. For example: “Why can’t we go to the police?” Claire pulls out a newspaper with the headline, “Man Found Dead in Car.” “This is the last guy who tried to go to the police.”

Genre: Drama/Adventure

Premise: The heretofore unknown tale of Pinocchio’s famous father, Geppetto.

About: Michael Vukadinovich’s script hit the spec market in 2011 and was snatched up immediately by 20th Century Fox for mid six figures. Vukadinovich began his career as a playwright (his most celebrated work being, “Trog and Clay (An Imagined History of the Electric Chair)” before moving into screenwriting. He has another project with Peter Dinklage attached called, “Rememory” about a professor who can record memories. The Three Misfortunes of Geppetto was a 2011 Black List script. Shawn Levy, the director of the Night at the Museum movies and, more recently, “This is Where I Leave You,” is attached to direct.

Writer: Michael Vukadinovich

Details: 118 pages

I decided to review this script today for one reason. To highlight the most spec-sale friendly of all the types of scripts out there.

There is no other type of script that has done better in the market over the last ten years. The formula? You find a fairy tale, then find a new angle to tell the story from. Whether it be the recent Malificent, about one of the most famous fairy tale villains in history, the edgy take on Snow White that was Snow White and the Huntsman, the dark spec sale from a couple of years ago, “Pan,” that reimagines Peter Pan as a serial killer. I’ve read 20 other spec sales in the past five years that have also succeeded with this formula. Hollywood goes nuts over this stuff.

And it’s not hard to imagine why. When a studio looks at a project, the first thing they do is ask how it can be marketed. Will the marketing be easy or difficult? The more difficult it is, the more stellar the other components of the screenplay have to be. But usually, there’s a tipping point – and it’s not very far down the line – where if the marketing is too tricky, they don’t bite.

With these kinds of screenplays, the marketing is always done for you. You say, “Snow White” and people immediately know who that is. There’s a comfort level there, like having your favorite coffee in the morning or turning on your favorite sit-com after a long day of work. So studios are always all over these scripts. In addition to Shakespeare adaptations, they’re one of the most bankable script approaches out there.

The Three Misfortunes of Geppetto places us squarely in the year 1919 where we meet Geppetto, an optimistic enthusiastic young man with his whole life ahead of him. But Geppetto can only think of one thing – the beautiful Julia Moon. Their love for one another is so powerful, you get the sense they fell in love BEFORE first sight.

The two know they’re spending the rest of their lives together, but before that can happen, the Depression hits and Geppetto’s family loses everything. This is when we first meet Geppetto’s evil nemesis, Edmund Vile (pronounced “Vee-lay!” he tells everyone). Edmund hates Geppetto and his perfect life and will do anything to destroy it. He starts by trapping Geppetto’s parents on a train crossing, watching gleefully as the train hits and kills them.

When Geppetto is later sent off to the war, he hears that Edmund has moved in on Julia. She refuses to marry him, but when word comes back, erroneously, that Geppetto has died, she has no choice. When Geppetto finds this out, it’s a race to get back in time to stop the wedding and be with Julia once more.

(spoilers) Geppetto succeeds in the knick of time, and ends up marrying Julia. But then Edmund has a witch put a spell on the two, making it impossible for them to have children. The couple will have to come up with another solution, a solution I’m pretty sure you can figure out. But the evil Edmund will do his best to stop it, in a last ditch attempt to destroy the couple’s life forever.

Jiminy makes a cameo in the script!

Jiminy makes a cameo in the script!

So let’s see if we can do this here. Pick a well-known fairy tale that’s in the public domain. Let’s say… Beauty and the Beast. Now look for a new angle to tell the story from. We could set the story in modern times? That could make it fresh. We could make the girl the “beast” instead of the guy. Role-reversal usually works. Or maybe we tell the story on a planet inhabited by beasts, and the girl is the only “human” and therefore a “beast” to them.

I’m only half-joking with these ideas. Obviously, I’m making this sound a little easier than it is, but I bet if you spent an entire week trying to come up with a fun fresh take on a fairy tale, you could. Of course, the second ingredient to this meal is that you have to love these kinds of stories. If you’re writing strictly for cash, the reader can tell. That’s what’s allowed “Geppetto” to stand above its competition. You can tell Vukadinovich loves his subject matter.

I’m not sure I’ve ever read something so unapologetically saccharine. “Geppetto” wears its heart on its XXL sleeves, pumping its sugar-laced blood directly into the reader’s veins for good measure. Geppetto, with his idealistic world view and his stay-positive attitude despite one tragedy after another makes it impossible to root against him.

Indeed, we talk about making characters likable all the time. One of the easiest ways to do so is to bestow tragedy upon tragedy on your character. We see that here, with his parents dying, with Geppetto and Julia not being able to have kids. Poor Geppetto even has to watch a baby whale die!

But what if you want to take your character from likable to lovable? Spiking the likable punch requires never having your hero sulk about his misfortunes. Have him stay positive and keep fighting. No character is more likable than the one who stares adversity in the eyes and keeps on fighting. Think about it. Who are the people in life you most admire? Chances are they’re people who keep fighting no matter how bad it gets.

Where Geppetto stumbles is in its structure. It sets up its story nicely. And then when Geppetto goes off to war, the story goal arrives – he must get back to Julia before she marries Edmund. (spoiler) But that goal is achieved on page 75. And there are still 45 pages to go. “Geppetto” decides not to replace this goal with a new one.

Instead, the goal is shifted over to Edmund – His goal becomes to ruin Geppetto’s and Julia’s happiness. You can probably hear me groaning. I don’t like non-specific goals. They don’t have that clean understandable objective that the audience can get behind. I can understand stopping a wedding. Destroying one’s happiness is too vague. And it shifts the goal away from the main character, which is always a dangerous thing to do, especially as you’re entering your last act, when, preferably, you want your hero to be his most active (if he has no goal to pursue, then by definition he’s not going to be active).

So that really hurt the script, and it’s something I’m sure the studio has been trying to address in the rewrites. Another problem is that “Geppetto” loves its influences a little too much, those influences being Forrest Gump, The Princess Bride, It’s a Wonderful Life, and Amelie. True love is mentioned numerous times here. We also start in the present with a grandfatherly character telling his grandson this tale. We have fun little flashbacks, a la Forrest Gump, of great grandfathers, great great grandfathers, and great great great grandfathers, dying of heart attacks. And Edmund seems almost beat for beat, a Mr. Potter clone. Sometimes reading Geppetto was like driving down memory lane for your favorite movies.

Despite that, the script has such an earnest idealistic love for its story, and Geppetto is so darn likable, that the script survives this and the structure problem. It’s an unexpectedly sweet tale that is sure to give you goosebumps at least a couple of times. And, for the most part, the proper way to approach this kind of script.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Remember that when you shift the goal that’s driving your story over to your villain, you are making your main character inactive or reactive. Since audiences tend to like characters who are active (who drive the story), this is a dangerous route to take. However, if you do it, I’d advise doing it in the first half of your screenplay as opposed to the second. The second half is where you want your hero the MOST active. For example, in Star Wars, the movie starts off with the villain having the goal (Darth Vader is trying to get a hold of the Death Star plans). But in the end, Luke has the goal that’s driving the story (to destroy the Death Star).

Genre: Drama

Premise: When a retired criminal gets back in the drug game, he starts taking out the organization’s dead weight, having no idea that one of his targets is his son.

About: Bill Kennedy has been steadily moving up the ladder, having recently penned the weird but kinda-funny Haley Joel Osmet comedy, Sex Ed. He’s also one of the bigger writers on the series, House of Cards (he’s written 8 episodes), and recently adapted “Cyber Storm” for Fox. That project is about a massive snow storm that cuts New York off from the rest of the world (and, of course, chaos ensues). This script, The Fixer, finished with 7 votes on the latest Black List.

Writer: Bill Kennedy

Details: 115 pages (4/9/13 draft)

Anybody here hear of Charles Bukowski? He’s a semi-famous American writer who wrote some pretty great books in the 60s and 70s. He was also strongly opinionated. He thought a whole lot of other writers sucked. In fact, it was rare that Bukowski came across anything that he liked.

Now you have to remember, Bukowski lived back in a time before Amazon and Goodreads. Outside of recommendations from the New York Times, the only way to find out if a book was any good was to actually read it. The insanity, right? So Bukowski used to sit in the library and open book after book, reading as many pages as he could muster, before throwing them down and moving on to the next one. “Why doesn’t anybody SAY something?” he would ask. “Why doesn’t anybody SCREAM OUT?” he wanted to know.

He hated so many of the books he opened, he started to wonder if there was any good writing anymore. Then he came across a book called “Ask The Dust” by John Fante. “The lines flowed easily across the page,” he said. “Each line had its own energy and was followed by another like it. The very substance of each line gave the page a form, a feeling of something carved into it. And here, at last, was a man who was not afraid of emotion. The humor and the pain were intermixed with a superb simplicity. The beginning of that book was a wild and enormous miracle to me.”

Wow! Talk about an endorsement. Isn’t this what we all hope for? To pick something up and be so taken away that the very foundation of our being is shaken?

I bet you’re wondering right now, is The Fixer the next great script? The next Desperate Hours or Nightcrawler? Had I found something with the kind of passion and power to make me stand on the metaphoric mountain tops and demand the world read it, like had happened with Bukowski and Ask the Dust?

In a word, no.

But, I will say this. I read the first five pages of seven professional scripts before I read The Fixer and The Fixer was the only one that attempted to grab me. It was the only script that seemed to WANT me to read it – reminding me of Bukowski’s experience. The first scene finishes with this voice over line: “I’d kill the cockfuck if I could. But I can’t, and I need money to run away, to start over. So I’m going to have to kill these guys, who happen to be friends of mine.” A few pages later, a criminal is so mad that McDonald’s won’t serve his son a Happy Meal because it’s before 10:30 AM, he puts a gun to the checker’s head and tells him, “Get me a motherfucking happy meal.”

This is a script that wants to be read.

I’ve said this before. While not every story is meant to be told this way, most scripts need an edge to stand out. This script had a big ole heaping of edge. BUT. Grabbing someone’s attention and keeping someone’s attention are two different things. The Fixer grabbed me. I prayed it wouldn’t let me go.

50-something Joe is a Fixer. I must admit, I’m not clear on what that is. But according to the few clues we get, it means Joe matches business people together, and then takes a cut of their business. Joe has been out of the game for awhile but he’s going stir-crazy at home. His wife is battling severe depression and rarely leaves the bedroom. Joe wants back in the game.

A friend sets him up with a local drug dealer, Terrance (the guy I mentioned earlier who demanded a Happy Meal), and Joe starts helping him get rid of the dead weight in his business. Joe finds out pretty quickly when he looks into the books that someone is shorting Terrance, and the two start trying to figure out who it is.

Meanwhile, we meet Nick. Nick is Joe’s son, a perennial screw-up. Nick’s harboring a secret from his father – that he’s gay, which keeps him from telling his dad anything that’s going on in his life. Nick gets a job offer to start selling drugs. This is his chance to finally make some money, to show his father that he’s worth something, so he takes it. The problem is, his deadbeat boyfriend, Mark, keeps injecting just as much as he’s selling. Naturally, this leaves him short come pay-up time.

As you might have guessed, Nick is working for Terrance, which means Nick is unknowingly working for his father. And when his father unknowingly pinpoints him as the dealer who’s shorting Terrance, Nick is given less than a week to find the money or die. Will Joe figure out he ordered his own son’s killing before the trigger is pulled? Gosh-darnit I hope so.

The Fixer has a pretty nice premise. You have some nice irony here. A man who unknowingly orders a hit on his son. And Kennedy’s put a lot of work into the character stuff in general. This is what good screenwriters do – every single character has something going on. They’re not paper characters. They’re real people with real problems.

Joe’s wife has severe depression and stays home all day, slowly sucking all of Joe’s life away in the process. Nick is secretly gay and terrified to tell his father. Terrance is still in love with his son’s mother, but she won’t give him the time of day. He’s running this business so he can woo her back with a good life.

Despite this, there were other parts of Joe’s character that were bothering me. Although he clearly starts as our main character, he kind of gets moved to the background. He only seemed to pop up to keep Terrance in check every so often. When you introduce someone as the captain of your ship, we expect to see them at the wheel. Joe wasn’t at the wheel very much.

I started to wonder why Kennedy was doing this. And then I realized, Joe is the only character here who doesn’t have anything at stake. Nick is 5 figures in the hole and needs to find the money to save his life. Terrance needs this business to get the love of his life back. But why did Joe need this? If this all falls apart, he goes right back to his previous life and, presumably, could go ahead and hook up with another drug dealer and start over again.

Also, Kennedy didn’t make it clear enough what a “Fixer” was. We’re told, in Joe’s own words, that a Fixer is someone who brings two business people together and gets a cut of their business. But then Joe goes and leads a drug operation. Does this also fall under the definition of “Fixer” as well? Or is he doing this independent of his old job?

A writer can never forget that while something may be obvious to them, they are not the audience for their scripts. Most of the audience won’t know the details of their world. Therefore, it’s up to the writer to explain them and make them clear. I didn’t get that here.

Finally, I didn’t get the sense that Kennedy really knew this world. He knew more than most. But as far as the specifics of how a drug operation was run, a lot of stuff felt muddy. Here’s something to remember. When you’re writing any kind of criminal movie, your bar has to be Scorsese. One of the reasons his movies are so successful is because he leaves no doubt that he knows this world inside out. We get details on top of details on top of details about how the drug trade works, the casino trade works, the financial trade works. That’s the kind of specificity you have to bring to the table because if you don’t, the script always feels lacking in a way the audience can’t quite put their finger on.

How do you achieve this kind of realism? You may not be able to physically go into the drug trade to do research (although I’d be impressed by any writer so dedicated as to do this). But you can still watch documentaries, read nonfiction books, go to message boards that have real people who do this kind of shit to talk to. I just always feel a little cheated when the subject matter I’m reading about feels fudged.

The Fixer started off with a bang, and was pretty good in places. But in the end, it didn’t quite keep my attention.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: To understand if your character has the appropriate level of stakes attached to his character, you simply ask, “If this character fails, what do they lose?” For Joe, if this drug operation fails, he goes right back to where he was at the beginning, where the worst problem he was dealing with was that he was bored. I don’t think those stakes are high enough. (I suppose you can make the argument that the stakes are his son’s life, but not only does that development come late in the script, but those stakes feel indirect, since he has no clue that his son’s life is even in danger. – This brings up an interesting question – does one need to be aware of one’s stakes for them to work?)