Search Results for: F word

Genre: Sci-Fi/Horror/Drama

Premise: Amid a rash of cattle mutilations in the ‘80s, a rural veterinarian holds an alien captive with the desperate hope that its miraculous healing biology can save his terminally ill wife.

About: This is the runner-up in the First Page Showdown. If you’re wondering why we’re reviewing the runner-up and not the winner, it’s a long complicated story but the gist of it is, the winner hadn’t finished his script yet and so we’re waiting on that before we can review it. Actually, that wasn’t long or complicated. It was pretty straightforward. Okay, let’s get to the review. Oh! And remember that we have Halloween Logline Showdown coming up next week. Get those loglines in!

Writer: Mark James

Details: 94 pages

Here’s the first page if you want to reacquaint yourself with it.

Lucky us.

We got a horror script just a week before Halloween Showdown! Sometimes the script gods shine down on us.

BUT!

The script still needs to be good. And the whole reason I picked this first page to compete was because it felt like a different kind of alien movie.

Let’s see if my instincts were right.

The year is 1985. We’re in Nebraska. We meet 30 year-old Dr. Lee Crutchfield as he is elbow deep inside of a dead cow’s rectum. Lee is a vet and although he’s seen a lot, this is not a normal Tuesday night for him. This is actually quite rare.

Word on the street is that cows from all over the local area have been getting mutilated. But Lee’s not buying it. He thinks an animal did this and is vindicated when a rabid badger pops up and he shoots it dead. He tells the rancher he has nothing to worry about, grabs the dead badger and heads back to the clinic to do tests.

Before he does that, though, he heads over to the hospital to see his late 20-s wife, Blair (who he calls “Mother Bear”), who has some sort of weird disease that causes dementia. Her situation is getting worse by the day but Lee is not giving up.

Back at the clinic, Lee spots the dead badger levitating, only to realize it’s being shuttled away by a cloaked 8 foot alien. Lee is able to neutralize the alien with a cattle prod and chain it up. Although the alien is coy at first, it eventually comes clean regarding having the magical ability to cure.

While all this is happening, an Omaha FBI agent named Annabelle Sable shows up who seems to have some knowledge about these aliens. She tells Lee that these off-worlders are not to be trusted! Everything they say is a lie. But all Lee hears is “healing.” So when his wife goes into a coma, Lee decides he’s using the alien cure to save her. But at what cost? And what happens if it doesn’t work?

I had a lot of thoughts swimming through my brain when I finished this script. I knew I could take the review in a familiar direction.

But since this all started with a First Page contest, the question that seemed the most relevant was, “Did I get the script I expected to get from the first page?”

The answer is no.

That’s not a bad thing. It’s just that when I read that first page, I imagined this thoughtful interesting take on aliens where the writer approached things from an angle that we hadn’t seen before. Cause this is a movie about aliens. And most movies about aliens start out with an on-the-nose scene that screams from the mountaintops that the movie is about aliens (i.e. a spaceship in the sky).

By approaching it via a dead cow’s rectum, you told us that this was going to be a different kind of journey (not unlike how we started in Adam Sandler’s rectum in Uncut Gems and got a totally different movie).

And while I suppose you could argue the script does turn out to be different, it ended up feeling too familiar when it was all said and done.

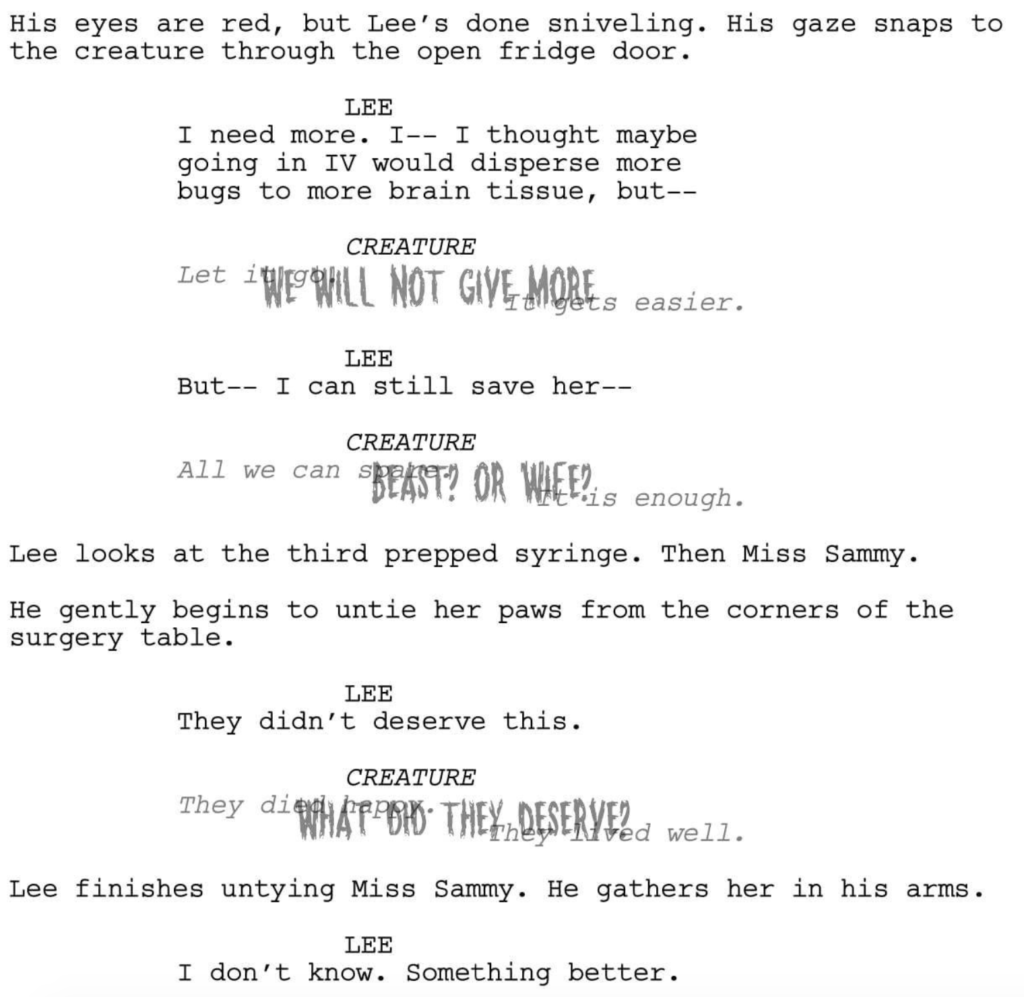

To the writer’s credit, he takes creative risks, the most visual being the alien’s dialogue. This is how all the alien dialogue looks:

What I liked about this choice was that an alien is going to look weird. It’s going to look different. This dialogue style captured that difference in a visual way. When we saw how different it was from normal dialogue, we subconsciously imagined the alien. Which was cool.

But the dialogue was hard to read. The middle part often covered the regular text on either side, which meant I had to squint and move the page around to see what the alien was saying. James also fades the regular text out as the script goes on until it’s practically invisible. So I wasn’t sure if that text even mattered?

Finally, I wasn’t sure how I was supposed to interpret the dialogue. The middle section always contradicted the ends so… I guess that meant the alien was always lying. But it’s still spoken dialogue so didn’t that mean Lee could hear it? All in all, as creative as it was, I felt it was more trouble than it was worth.

The script’s strongest suit is its emotional core – the relationship between Lee and Blair. But I’ll be honest, I had trouble giving in to it. For starters, they’re both late 20s, early 30s. And Blair has dementia. It didn’t read right. A 28 year old with dementia? I’m sure it happens but it happens rarely enough that it creates that dreaded “reading hiccup.” And then the characters called each other Mama Bear and Papa Bear, the kind of nicknames old people use for each other, which confused me, because these characters were young. It just created this clunky vibe to the proceedings that prohibited me from fully enjoying what I was reading.

And while I don’t mean to pile on, this script doesn’t resolve my belief that you can make aliens scary in the way that you can make traditional earthbound creatures and monsters scary.

What happens in The Harvester – and what happens in a lot of these scripts that try to combine horror and aliens – is that, at a certain point, the writer learns that making them scary doesn’t make sense. So it always turns out the the alien is helpful instead of hurtful. We see that here with the alien offering his magical medicine that can heal anything. And, at that point, what are we scared of? We’re not. In retrospect, I’m not sure I was ever scared. And I’m someone who routinely watches scary movies through my fingers.

I mean how scary of an alien can you be when you’re easily restrained by handcuffs? It just didn’t make sense. And I don’t want to dog James because I’ve been down this road before myself. With my own alien-horror scripts which ran into this same problem, and with scripts from other writers that I’ve tried to shepherd. But none of them can ever quite figure out this “aliens being scary” thing. You can do it in flashes. But over the course of the story, it doesn’t make sense for aliens to be scary. Why come 100 light years if you’re going to hide underneath beds and say “boo?”

Overall, as hard as I tried, I couldn’t connect with this script. The horror wasn’t horrifying enough. The sci-fi hit a wall. And the drama was affected by little choices that resulted in an unnecessarily clunky relationship journey.

It wasn’t for me but I’m curious what all of you think. Check out the script below.

Script link: The Harvester

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whenever I see a writer offer three genres for their script, the first thing I think is, “This writer doesn’t know what kind of story he’s telling.” And that’s how I felt when I read this. “I’m not sure this script knows what it wants to be.” It leans most heavily into the drama side of things. That’s when it’s most comfortable. Cause I think James understood that storyline the best. But this alien who’s sort of dangerous but not really dangerous dictating the majority of the narrative had me scratching my head. It just felt like there was a better story that could be told here. And my gut tells me simplifying the genre is a good place to start.

So I’m sitting there watching Talk to Me, the A24 Australian horror movie you might have seen the trailer for. It’s the one where a bunch of teenagers are in a basement and one of them holds a hand statue and then goes into some sort of trance.

The movie is pretty good. But it made its fair share of screenwriting errors. Basically, the plot goes like this. A teenage girl, Mia, hangs out with this family all the time because her mom died. She’s got her friend, Jade. And then Jade’s younger brother, Riley.

This trio occasionally hangs around a cool group at school, led by tough-chick Hayley, and Hayley’s muscle, Joss. This group loves to play this game called, “Talk to Me,” where they bring out a hand statue, strap you into a chair in front of it, you hold the hand and say, “Talk to me,” then follow that by saying, “I let you in.”

As soon as you say, “I let you in,” whoever’s in the chair sees a [usually gruesome] dead person sitting in front of them. Nobody else in the room can see this. Just the person in the chair. This creates a level of doubt where everyone can write the experience off as fake, much like when two people push the planchette on a Ouija board. You can always blame the other person as the pusher.

Except everyone in the room participates in the experience so that sort of negates the idea that they’re faking it. But we’re not going to nitpick.

Mia seems particularly affected by her experience, where she saw a couple of gnarly dead bodies. But it’s when Riley goes under that the crap hits the air conditioner. Riley is channeling Mia’s dead mother.

Mia is so taken by the chance to talk to her mom that she prevents Riley from stopping the experience before the mandatory 90 seconds. Riley starts going ballistic, bashing his head into anything he can find, nearly killing himself before they’re able to detach the hand from him.

This results in Mia being banished from the family, which sends her back home to hang out with her dad. When Mia sees her mother’s apparition again, she finally answers the question about whether she killed herself. She didn’t. And the person who did is two rooms away from her. Her father. Time to run.

You may have snooped out a couple of the screenwriting issues from that synopsis. The first is that the possession rule is shaky. In fact, we’re not even sure people are being possessed for three-quarters of the movie. Mia is not possessed despite going through the process. She sees other spirits, like her mom. But she’s not possessed.

Then, near the end, we lean heavily into the injured Riley being possessed. And then, of course, Mia’s father being possessed. Whoever’s inside of her dad is trying to kill her.

You can tell that the writers started to realize near the end of writing the screenplay that, “Oh, they’re possessed! So we can do something with that!” So then they rush to pay off a possession storyline that they never really set up.

It’s fine to do this. It’s a natural part of screenwriting. You figure things out while you’re writing the script. But once you figure something big out, you have to go back and properly set it up.

Ditto the dad. They didn’t even mention the dad for the first 70% of the movie! I didn’t know she had one. How could I? She was always at this other house. And the writers leaned heavily into this idea that this other family was taking care of Mia. So we assumed she didn’t have family.

To not only tell us she had family, but to build the crux of Mia’s entire storyline around what her father did to her mother was clunky to say the least. A good screenwriter is going to realize that if they want to use this ending, they need to go back into that first act and properly set up the dad. Then keep him in the story throughout the second act.

As I was pondering all this, a question popped into my brain: Does it matter? Or, more specifically, would this have mattered in regards to how well the movie did? It’s got a 94% critic score on Rotten Tomatoes. It’s got an 82% audience score. It made 50 million dollars in the U.S. and nearly 90 million worldwide.

Would making those changes have affected these numbers in a positive way? Because if you look just at the movie, it’s really well put together. The main actress who plays Mia, Sophie Wild, is great. She’s going to become a star. The rest of the cast is really good. There are no weak links.

The cinematography is great. The directing overall has no weaknesses (they were particularly convincing in creating a “teenage atmosphere”). Also, the hand sequence WORKS. Whatever it is at the center of your fantastical story, it has to be convincing for the viewer to suspend their disbelief. If it’s hokey or dumb, they’ll immediately check out. And the “talk to me” stuff was perfect.

Most importantly, the movie was scary. I did the thing where I put my arms up in front of my face half-a-dozen times cause I saw something weird in the corner and it started moving and I didn’t want to know what the f*** it was.

So, if you do those things: You have a convincing mythology, you have plenty of legitimate scares, you have characters who we’re on board with – you can make screenwriting mistakes and it be okay. It’s similar to what I tell comedy writers. If your script is funny, you can have the worst plot ever. It doesn’t matter. Ditto with horror. If it’s scary, you can make mistakes.

But the purist in me still believes that if you fix those mistakes, your movie is going to have better word-of-mouth which means more people are going to want to see it. I think it’s telling that the audience score is lower than the critical score here. Audiences may have been a little frustrated by the sloppiness in the storytelling.

Look no further than what happened to Exorcist: Believer this weekend. Now I didn’t see the film. But I knew that the baseline they were building predictions off of was 30 million. Because that’s what the predicted ROI was for this particular advertising package. Now, the box office could go well above that number or below it. And it depended on if the story was good.

Guess what?

It wasn’t good. It has a 22% Rotten Tomatoes score and a 59% Audience score (which will probably go down once more reviews come in). It was made clear early on on social media that this one was a stinker. And so all those potential moviegoers who were thinking about going on Saturday who were going to pump up that box office to the high 30s, maybe even 40 million dollars, they decided to stay home, and the movie made 27 million bucks.

In David Gordon Green’s defense, I’ve never been able to figure out the key difference between an exorcism movie that works and one that doesn’t. For all intents and purposes, the original Exorcist should not have worked. It’s long. We’re stuck in this house the whole time. Some characters disappear for 90% of the movie. Others show up halfway into the movie.

I just remember that movie feeling so real. It felt like how an actual exorcism situation would happen. That realism is what sold it for me. And even though all these exorcism movies since have given us convincing possession performances, none of them has felt as authentic as The Exorcist.

In other words, trying to recreate the authenticity of one of the most authentic horror movies ever is a hard task to pull off. None of the other Exorcist sequels have been able to do it. I’m shocked, like the rest of the industry, that Universal paid 400 million for the rights to try and change that pattern. A lot of people thought they were dumb. Believer’s critical and audience reception is proving them right. It looks like this franchise is going to end up on the bottom of a concrete stairway.

Last week over 250 writers sent me the first page of their screenplay. Only 6 of those made it to the First Page Showdown. Here are 10 that didn’t make it. I explain why.

***SUPER DEAL*** I’ve decided to give out four SUPER-DEALS this weekend. If you’ve got a feature script or a pilot, I can give you 4 pages of stellar notes (with an emphasis on the first page if you want!) for $200. I’m giving out 2 of these with this post and 2 in the newsletter. To get one of the 2 slots here, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the promo code: SUPER DEAL. Hurry up. They’ll disappear quickly! ***SUPER DEAL***

Okay, an update on the First Page Showdown. Our winner, Neobiata, it turns out, doesn’t have a full screenplay for his entry. I told him to write it over the next two months and I would review the script when he’s finished. But this is not going to become a regular thing. So don’t think you can start entering loglines into Logline Showdown and write the script later if you win. I’m allowing this because it’s the first time it’s happened and I’m feeling nice!

So I’ll review the second place script next week. I’m putting all of my focus on the newsletter right now, which is going to be a blast. After my Ripple review, someone contacted me who has access to a time machine, which they’re sending to me. It can only be used once and I have a really fun way to use it that I’m going to save for the newsletter. If you want to be on my newsletter list, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line, “NEWSLETTER.”

Okay, let’s take a look at some first page entries that didn’t make the cut. I want to take you through my thought process as to why they didn’t make the top six. Hopefully, you can learn something from the analysis. And feel free to tell me that I’m wrong and that one or more of these deserved to be in the competition!

TITLE: BELIEVER

This one lost me at the very first line. “KRYSTAL, 20, heavily tattooed on all but her angelic face, soaks eyes closed in a steaming bath.” It’s too clunky of a sentence. There should be commas surrounding “eyes closed,” but there are not, which makes us read it as “soaks eyes,” which, of course, doesn’t make sense once you get to the trailing, “closed.” So you then have to reset to read the sentence correctly. If you’re making your reader do that on the first line, you’re effed. Very few readers are going to forgive you for that.

The scene actually has a potentially interesting situation going on. You’ve got a mysterious, maybe even threatening, person at the door. A suspenseful beat follows. But then things get confusing. It’s implied that whoever was at the door has left in the elevator. However, we also meet the tenant across from her with a clunky line of its own – “An eye dances with excitement…” – plus I’m not sure if we’re in his apartment (since “APARTMENT ACROSS THE HALL” is presented as a slugline) or we’re still in the hallway. This page could be smoother.

Logline (Thriller): An alcoholic with a history of mental illness escapes a murderer and then fights to make sense of her fragmented “visions” in order to save the next victim before the killer’s twelve-hour deadline.

TITLE: 10 CENT BEER NIGHT

This was actually a pretty good page. Something is going on. The writer does a solid job creating a visual scenario. But as I attempted to consider whether to post it, I read it again and I noticed that something was missing. I couldn’t figure out what it was, at first, but it finally came to me. There was no character to latch onto in the scene. I felt like I was watching everything from a thousand feet above. Later on the page, we do get a dad and his son. But, still, we don’t know these people. They’re not even given a name. So I still feel nothing in a scenario where I should feel everything. This is an interesting premise, though. I would encourage the writer to rewrite this first page and use a character to put us into the mix so that we FEEL what’s happening.

Logline (Comedy): When a well-meaning father tries to celebrate his rebellious son’s 18th birthday, they incidentally attend the most disastrous event in baseball history — Cleveland’s 10¢ Beer Night — and must contend with a crowd of streakers, drunks, and all-out barbarians to survive the night.”).

TITLE: NASTY NEW YEAR

Sometimes it’s one mistake that does you in. That was the case with this page. Here’s where I officially gave up on the entry: “In the first row, Hannah notices a CHATTY GIRL (14) with a bulging PIMPLE on her chin. Becomes obsessed with it.” What does this have to do with anything? You’ve just shown a character lose her focus, then hurriedly regain it in a basketball game… why the random shot of a girl with a pimple and our heroine obsessed with her? I’m now imagining a scene where my heroine is standing in the middle of a game staring at a girl with a pimple in the stands. Maybe if there was a reflective windowed door and our heroine caught her own reflection and saw a pimple on her own face, maybe I could see her becoming obsessed with that. But becoming obsessed with a random fan’s lack of a skin care routine makes me think there are going to be a ton of random moments in this script. I have no interest in that. I like focused narratives with clear plots. This doesn’t appear like it’s going to be that.

Logline (Horror): An anxious young woman whose body has been secretly prepared since childhood to become another mind’s host on New Year‘s Eve must outsmart the devious parasite-to-be – her anti-aging obsessed mother.

TITLE: DERANGED

I don’t know what a Mercedes W124 is. So I’m already behind the writer. I don’t know what “skinned vehicles” means. Like their paint is stripped off? I don’t know what, “sits like if the seat is tickling his butthole” looks like. Does that mean he’s having an uncomfortable experience? A joyful experience? Either way, it’s not a good description. To the writer’s credit, they’re creating a bit of suspense here. We want to see who these guys are waiting for. But a lack of clarity in the writing followed by an ill-informed line of description told me that I was going to be getting a lot more of those things if I kept reading.

Logline: A quiet, vengeful husband puts his family in a life-or-death situation when he targets the prime suspect in his wife’s murder: a ruthless Mafia hitman.

TITLE: HALL OF FAME

When I see, “Hall of Fame,” I’m thinking ‘sports.’ So I didn’t understand where I was or what was going on at first. In all of my life, I’ve never read the word ‘cloche’ before. You can get away with that sort of thing sometimes, if the word doesn’t matter. But this word is pivotal to the reader understanding what’s going on and since no reader will ever give you the courtesy of looking a word up, you’re pretty much screwed right there.

I was still willing to give the page a chance but then we get “sparing” instead of the proper word, “sparring.” And now you’re really dead. I’ve gone from confused to never seen that word before to wrong word. This is why feedback is so important, guys. You need somebody telling you these things so that you’re not killing your opportunities. Cause a screenwriter can spend five years getting to the point where a legitimate person agrees to read their script and they come into that opportunity like the Chicago Bears, down 31-0 in the first quarter. You can’t recover from that.

Logline (Horror/Thriller): When a popular news anchor is abducted and imprisoned in a macabre gallery filled with celebrity exhibits, she must exploit her own fame as both a weapon and a means of escape.

TITLE: HEMMVILLE CREEK

Sometimes, writing just isn’t easy to read. This has nothing to do with screenwriting per se. It’s more about writing in general. If I’m doing double-takes on basic sentences, that’s a problem. This second sentence here: …“as a PICK-UP TRUCK with GLOWING HEADLIGHTS also rumbles out…” Why, “also?” “Also” shouldn’t be a part of this sentence. “…from the woods dirt road…”. That doesn’t make sense. Later on the page we get, “He was healthy who had potential to become something in his life.” That’s a massive writing error on your first page! If this is what we’re going to get on page 1, the page that the writer pays the most attention to, then we, as readers, know that we’re going to get a lot more of that if we keep reading. So you gotta clear things up. Because, other than that, there’s something big going on here. There’s some potential to grab the reader with this opening. But if they’re fighting through the sentences, they can’t appreciate the story.

Logline (Whodunnit/Thriller/Drama): After her innocent 18-year-old son becomes the prime suspect to a Halloween party massacre in their small town, a Sheriff only has 13 hours to find the real killer before the FBI arrive and take over.

TITLE: DON’T SEND HELP

This is, actually, a solid page. I had about 250 entries. I’d put this in the top 40. Maybe top 30. We are establishing something interesting – which is that this woman is stranded on an island. That alone is worthy of getting people to turn the page. But is it the best opening Steph could’ve gone with? That’s debatable. Cause there’s nothing going in the scene. It’s a scene that is, solely, establishing information. It’s not doing so via any kind of dramatic situation. For example, if we started on this character sprinting through the jungle as we try and figure out why she’s doing so (Is she running towards something? Running away from something?). Then we hear a noise (a boat horn or a plane, maybe) and she emerges onto the beach (and this is where we realize she’s stranded on an island), she runs to the water to try and signal the passing vehicle. You’ve established the same thing you’ve established on the page you already have. But you’ve added a dramatic element. Or you can pull a reversal. Start on our heroine tanning in paradise. Establish the peaceful beauty. Then, ever-so-slowly, pull away from her, gradually establishing the beaten-up beach, the SOS sign, some remnants of former temper tantrums, until we realize she’s stranded on an island. Way more interesting than an on-the-nose, “FU” to the world for being stranded here.

Logline (Survival Drama): When a devoted wife and mother is rescued after being marooned on a deserted island for six months, her family is forced to reassess old behaviors, given that she’s lost her taste for living a normal, civilized life.

TITLE: HARD DOLLAR

A couple of issues stick out to me right away. You’ve got three blocks of 4-line paragraphs. That’s going to agitate a lot of readers. Readers like to see white space. Not big chunky blocks of text right away. Another issue is one I see a lot, which occurs in the very first line: “Unlocking a door labeled Legion Detective Service across its cracked glass, VIC LEGION (40s) tosses a horse-racing program

on…” Notice how this line reads backwards. An action occurs before we’ve met the person performing the action. If you do that enough, it’s uncomfortable to read because we’re only forming an image AFTER the sentence, instead of right away. Instead, keep it basic. “VIC LEGION (40s) unlocks a door labeled ‘Legion Detective Service’ across its cracked glass.” It’s simple changes like this that make a big difference. I’d also try and give us a more unique opening. A guy shows up to a private eye cause his wife is cheating. That’s the most obvious possible way to start a script in this genre. Instead, look for ways to subvert the reader’s expectations. Give them an opening scene they wouldn’t expect to see in a detective noir.

Logline (Detective Noir): After narrowly surviving a brutal beating by his client, a private detective wakes up with achromatopsia, a condition where he can only see in black and white, and the voice of a drunken Humphrey Bogart offering him unsolicited advice on how to solve his cases.

TITLE: DO YOU FEAR WHAT I FEAR

This is where screenwriting gets tricky. Here’s the writer’s pitch: “This is a Christmas horror comedy… I kinda love it… it’s like SCREAM meets ELF, but also a tribute to the fun 80’s horror movies I loved growing up like Night of the Demons, Return of the Living Dead, Night of the Creeps and Gremlins. It’s full of sex and violence and wrongness and fun.” It’s a fun pitch but the second I read this part — “Ah, f**k it. He’s a little a$$hole anyway.” They laugh. And cough. And laugh. And cough.” — I checked out. I hate these two people. It’s no different from a first impression. A girl could meet the man of her dreams but, if within the first five seconds, he accidentally spits on her while he’s talking, that’s all she sees. Any little mistake during a first impression has an outsized impact on the other person. Another thing to keep in mind is that comedy only starts working once you’ve established that type of comedy. If you have your highly sarcastic characters start off on page one saying sarcastic funny things, the reader doesn’t know they’re sarcastic yet! How could they? It’s the first page. So they may take their lines seriously. It’s only after being with the characters for 15-20 pages that we understand their sense of humor. So starting with a mean joke before you’ve established that as the dominant type of humor could turn off a lot of readers.

Logline (Horror/Comedy): After being fired by her not-so-jolly dad on Christmas Eve, a heartbroken Karen Claus discovers she’s the target of a masked killer grinch seeking revenge against Santa for the coal he received as a child.

TITLE: TRUTH, JUSTICE, AND THE AMERICAN WAY

One thing you just can’t do is start your script with nothing happening then jump into a flashback. Why not just start in the flashback already????? What’s the point of seeing a person writing random words? Why is that worthy of creating a gummed up first scene with two time periods? It’s not. You don’t have time to mess around with screenplays. You’re always looking to get to the meat ASAP. Any time you’re not in the meat, you’re wasting the reader’s time. So if you are going to start with something before jumping into a flashback, make it a really big something where a lot is going on, not a small unimportant visual beat that leaves zero impression on the reader. Cause this is one of the few biopics I would probably be interested in. It’s the ultimate David vs. Goliath scenario. So use that first scene to grab us, not waste our time. You have freaking SUPERMAN for goodness sake. You’ll do yourself a huge favor by starting your first scene with Superman in it.

Logline (Biopic/Drama): The creators of Superman achieve the American dream, have it stolen, and fight like hell to regain it.

As always, I do logline consultations for $25! E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail to make sure you’re going into any e-mail query with your best logline.

”The Continental” draws heavy inspiration from The Godfather. Does it work?

You gotta give it to the John Wick people.

They optimistically charged into a seemingly impossible task.

They took a franchise built on top of thin characterization, thinner mythology, and overly-impressive production value and migrated it to a medium that’s all about characterization, needs mythology to thrive, and doesn’t have the money to pull off great production value.

But this is what Hollywood does. It expands. And it often expands without thinking. David Goyer was just talking about this on the Happy Sad Confused podcast last week. He was writing the DC movies when Marvel blew up and he was getting non-stop notes from the studio that they had to accelerate their plans to expand their universe, leap-frogging over a second Superman film to do Batman vs. Superman instead.

That decision was widely criticized for breaking the DCEU, as it attempted to expand a universe that hadn’t yet set its foundation.

Building a show around the famous hotel in John Wick (The Continental) sounds good in practice. It’s a hotel that houses assassins. I mean, how cool is that? But this is what’s tricky about screenwriting. “General coolness” isn’t the best starting point for a movie or a show. You need a more focused idea, even for television. The more specific you can get, the better.

Gray’s Anatomy, one of the longest running shows on television, wasn’t about “a hospital in Seattle.” It was about a group of first year doctors thrown into the fire in a hospital in Seattle. And if you want to get more specific, it was about a young woman whose mother, one of the most successful doctors in the nation, had recently been diagnosed with early-onset dementia, and the challenges our heroine had of trying to navigate the hospital as a first year doctor, helping her mother, as well as living up to her reputation.

In other words, you can’t just say, “The Continental, cool assassins” and you’re finished. You have to come up with an actual idea, something that can be expanded out into a compelling story.

So what did the writers come up with?

They decided to focus the story on the man who would eventually become the manager at the Continental, Winston Scott, and set the show 50 years prior, in the 70s. Young Winston is some big shot businessman who lives a straightforward life. He’s unexpectedly called into the world of the Continental after his black sheep brother, Frankie, who he hasn’t seen in ages, steals a literal mystery box from the infamous hotel.

The current manager of The Continental, Cormac O’Connor (Mel Gibson), kidnaps Winston to bring him in, and demands that he find Frankie for him, so he can get his mystery box back. This sends Winston into a criminal underground which he is unfamiliar with. This storyline intersects with a couple of others, including a rookie cop, KD, who wants to know more about the mysterious Continental hotel, and a team of funky criminals who use a karate dojo as cover for their small-time criminal operation.

The Continental starts out strong. My favorite moment is when Frankie uses the cover of a big party in the Continental to break into the hotel from the subway, going up through several floors to where a giant safe is. Then he hooks onto the safe with a chain that goes all way down to the subway, where an anchor dangles and waits for a train to come. The train hooks onto the anchor, yanking the the safe door off and allowing Frankie to complete his heist. It’s quite clever.

This is followed by a fun stairway escape set piece where Frankie is having to take on assassins that are both below and above him. I always say, the best set piece you can write is one where the reader is convinced there’s no way out. And it truly feels like there’s no way out for Frankie. But through brute perseverance, he somehow takes everyone down and escapes.

I was in at that point, crafting my application letter to the Continental Fan Club.

Unfortunately, the rest of the show never quite lives up to that opening. It does have a clear goal – Cormac (and by proxy, Winston) needs to get that box back. And it does have some mystery. What’s in that box?? It also has a little Godfather to it in that Winston is the outsider. He doesn’t want anything to do with the criminal world. So it’s a fun idea to force him into that world. And, of course, we know he’s going to end up just like Michael Corleone. So, technically, we’re invested in that transformation.

But that’s where The Continental made its first mistake. For something like this to truly hit, Winston has to be a BONA FIDE outsider. Cause we’re going for a “fish-out-of-water” narrative here, with a non-criminal being forced to engage with the criminal world. All the fun is in the contrast. That’s where your conflict is going to come from and the conflict will breed the drama that powers your episodes.

The problem was, Winston never felt that out of water. He was more like a fish being carried around in his own personal fish tank. Cause whenever he walked into a dangerous criminal situation, such as when he went looking for Frankie at the Funky Bunch Karate Dojo, his demeanor remained as calm and collected as if he’d received a preview of the John Wick movies from a time-traveling visitor, leaving him utterly assured of his survival and unfazed by any potential threats.

There’s a better creative option here. If Winston was more of a dainty nerdy financial guy who is all brains and no muscle, then we’re milking the fish-out-of-water scenario. Which is what you want! If he’s already comfortable being a bada$$, where’s the potential character growth? Cause that’s how he was in the movies.

The biggest problem with The Continental is that it doesn’t give us a character to love. We kinda like some of these characters. But we don’t love any of them. They could’ve easily fixed this by making Winston a true underdog. Place him a million miles away from the criminal world. Make him more of a nerd. The guy shouldn’t even know how to hold a gun. The more of an underdog he is, the more we would’ve loved him. I guarantee it.

In fact, I would argue that Frankie would’ve been a better Winston than Winston. Because, even though Frankie was a criminal, he was a rough-and-tumble plays-by-his-own rules criminal. He’s the opposite of the refined respectful professional criminals who work and stay at The Continental.

So at least with him, we can imagine how much he would need to go through to become Winston. A lot. Whereas the current Winston is already basically Winston from the movies.

The other big problem with this show is one that has nothing to do with the writing, and something I hate thinking about because I’m the screenwriting guy and I want to believe that any problem can be solved by the writer. But the truth is that every show you turn on for the first time is dependent on there being at least one actor who you say, “I want to know more about them.” There’s some perfect cosmic marriage between actor and character that, irrespective of the show, you just want to see more of them. The Continental does not have that.

I remember when I first saw Lost. That feeling happened almost a dozen times. Every actor who popped on screen, I said, “I want to know more about this person.” And, unfortunately, if you don’t have that, it’s almost impossible to overcome it. So, bad casting work by the show’s casting department.

I will say that they’re spending some legit dolla bills on this show. There are a lot of moments that could’ve been in John Wick movies. And setting the story in the 1970s does give the John Wick universe that slightly different feel required to separate the show from the films. And Mel Gibson as the big baddie looks to have potential.

I’m just not convinced they have a real story to tell here. And that probably has to do with the fact that they’re building the show on one of the thinnest cinematic universes ever created. And I’m a John Wick fan! It’s a fun cinematic universe! But it was never a universe designed for depth.

What’d you guys think?

Today’s article taught me a tremendous lesson about creating memorable main characters.

Genre: Article – Drama/Crime

Premise: Covers the unique job of Gary Johnson, a Houston cop who specializes in going undercover as a hit man to entrap murders-for-hire.

About: This article, which was written all the way back in 2001, was snatched up by indie super-director, Richard Linklater, who cast Glen Powell hot off the success of Top Gun: Maverick. He went and made the movie, which just premiered at Toronto Film Festival, and sold to Netflix for 20 million bucks, the biggest acquisition deal of the year. Linklater read the article all the way back in 2001 but couldn’t find an angle for it. It wasn’t until longtime collaborator Glen Powell came along (the two have worked together on three projects) that a movie emerged, as Powell zoomed in on the final three paragraphs of the article, which focused on a female client who wants to kill her boyfriend.

Writer: Skip Hollandsworth – article; Glen Powell and Richard Linklater – script

Details: about 4000 words

I’ve said it once. I’ll say it again a million times.

One of your primary jobs as a screenwriter is to look for stories that have a familiar element, then spin that element in a slightly different direction.

I’m not using the word “slightly” frivolously. That’s an important part of the equation. If you attempt to spin the familiar element too aggressively, it becomes unfamiliar, and audiences can’t connect with it.

Get Out spun a familiar setup – “Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner” – into a horror movie. Easy to understand. Beau is Afraid is a horror movie told through the lens of extreme anxiety. Nobody understood it.

Then you have the opposite mistake, where there’s no spin at all. That’s when you get movies like Blue Beetle. The exact same superhero origin story we’ve seen a million times already and, by the way, it involves a power suit that, literally, every superhero wears now.

We’ve seen a million versions of hit men. So it was a smart idea to flip that and say, “What if the hit man wasn’t really a hit man? What if he was a cop pretending to be a hit man in order to capture bad people trying to murder others?”

That’s a great starting point for a movie.

The article, appropriately titled, “Hit Man,” isn’t so much a story as it is a summary of the unique life of Gary Johnson. Johnson wanted to work in psychology but when he moved to Houston, he didn’t get his dream job. So he took some psych-adjacent work at a local Houston police office and stumbled backwards into his first murder-for-hire plot. A woman wanted to off her husband because he had taken to complaining too much about her spending. When a friend alerted the police, they threw Johnson into the fake hit man job simply because they had no one else.

Johnson went in with preconceived notions that he was going to have to put on some elaborate fake persona but the reality was the woman just wanted someone to hear what she was going through. Johnson listened, he secured the money for the hit, and the wife was immediately arrested.

Word spread that Johnson had an effective unassuming way about him that got people to open up, a crucial component to convicting these criminals, since you needed them to say, “I want to kill my spouse” for the arrest to hold up in court. So began a strange illustrious career of Johnson going on three hundred murder-for-hire calls in the span of 20 years.

The only call that went sideways was when a woman wanted her abusive boyfriend killed and when Johnson looked into her claim, he learned that the guy was, indeed, abusive. So he decided to help her instead of incriminating her. Which is the kernel of the story that seems to have inspired the movie.

I went into this article expecting to talk about concept. But the biggest thing that came out of it for me was the second paragraph. Here it is…

The man lives alone with his two cats. Every morning, he pads barefoot into the kitchen to feed his cats, then he steps out the back door to feed the goldfish that live in a small pond. He takes a few minutes to tend to his garden, which is filled with caladiums and lilies, gardenias and wisteria, a Japanese plum tree, and rare green roses. Sometimes the man sits silently on a little bench by the goldfish pond, next to a small sculpture of a Balinese dancer. He breathes in and out, calming his mind. Or he goes back inside his house, where he sits in his recliner in the living room and reads. He reads Shakespeare, psychiatrist Carl Jung, and Gandhi. He even keeps a book of Gandhi’s quotations on his coffee table. One of his favorites is “Non-violence is the greatest force at the disposal of mankind. It is mightier than the mightiest weapon of destruction devised by the ingenuity of man.”

The reason this paragraph spoke to me is because, in the last four screenplays I read, I didn’t have any feel at all for the main character. I knew, generally, who they were. But I didn’t *know* know. It’s hard to write a good story if the reader doesn’t have an innate feel for who your hero is.

The primary reason this happens in a screenplay is the writer’s reluctance to add detail. Threre’s a distinct lack of detail in the character’s appearance (an athletic frame tells a completely different story about a person than an obese frame). But, more specifically, there’s a lack of detail in their everyday life. As I read this second paragraph, I was overwhelmed by how quickly I knew this person. The fact that he has two animals he takes care of. The fact that he has this small pond with goldfish that he feeds every morning. That he tends to his garden. The fact that he meditates. Then he reads.

This morning routine tells us SO MUCH ABOUT Johnson. Just the fact that he has a morning routine and doesn’t wing it, tells us that he’s responsible. That he takes care of multiple animals tells us he’s loving. Meditation tells us he values giving time to himself. Reading Carl Jung and Gandhi tells us that he’s an intelligent man.

I probably know this character better in 10 lines than I do any character I’ve seen in the last 20 movies, despite spending two hours with each of them.

The next thing that caught my eye was this paragraph describing Johnson:

In law enforcement circles, he is considered to be one of the greatest actors of his generation, so talented that he can perform on any stage and with any kind of script. If he is meeting a client who lives in one of Houston’s more exclusive neighborhoods, he can put on the polished demeanor of a sleek, skilled assassin who will not sniff at a job for less than six figures. If he is meeting a client who lives in a working-class neighborhood, he can come across like a wily country boy, willing to whack anyone at any time for whatever money he can get.

In other words… ACTOR BAIT! This is one of things you should be looking for when reading an article or a short story that you’re considering turning into a screenplay. You’re looking for the kind of roles that actors would die to play. You should naturally extrapolate that out to the screenplays you write as well. Roles like this allow your main character to become different people which is the ultimate actor catnip.

I find it interesting that Linklater was unable to see the movie angle here. Because it’s pretty obvious. Here’s the last part of the article…

But not long ago Johnson did something out of character for him. He got a call about a young woman who had been spending mornings at a Starbucks in Houston’s Montrose area, talking to an employee there about the cruel way her boyfriend had been treating her. There was no way to escape him, she said. Her only hope was to find someone to kill him. She asked the Starbucks employee if he knew someone who could help. The employee called the police, who put him in touch with Johnson.

But before Johnson contacted her, he did some research into her case. He learned that she really was the victim of abuse, regularly battered by her boyfriend, too terrified to leave him because of her fear of what he might do if he found her.

This is what I call the “but then” hook. You don’t have a movie unless you have a “but then.” Of course it’s going to be fun to watch this police detective inhabit various costumes as he impersonates a hit man. Sooner or later, though, something needs to occur that gives us a plot for our movie! That’s the “but then.” “But then” this woman comes along who it turns out ACTUALLY NEEDS A HIT MAN. Cause her boyfriend is dangerous.

Now you can start to play with narratives, such as, does Johnson become romantically entangled with this girl when he starts to protect her? And who is this boyfriend? Is he a nuisance? Or is he connected to a more dangerous, potentially criminal, network? In which case, is Johnson now in over his head? Now you’ve got a movie.

Finally, when you’re looking for movies that don’t exist in the bigger flashier genres that keep Hollywood afloat (Sci-Fi, Fantasy, Action, Horror, Adventure), there must be the threat of death. You need those LITERAL life-or-death stakes. Cause you’re not giving us any flashy special effects to look at. You’re not scaring us to death. You’re not wowing us with your bottomless imagination. So you need to have the highest stakes possible. People hiring people for murder is a life-or-death situation.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Give your main character a morning routine and make it as specific as possible. This morning routine doesn’t have to be in your script. But you at least need to write it out for yourself. Because one of the most telling parts of who someone is, is what they do when they wake up. Do they go on a five mile run? Do they go order 5 sausage and egg McGriddles from McDonald’s? Do they tend their garden? Do they go straight to social media? Do they have an elaborate half-an-hour skin care routine? Note how each of the things I just listed paints a different kind of character. You can create that same effect when describing your own character’s morning routine.