Search Results for: F word

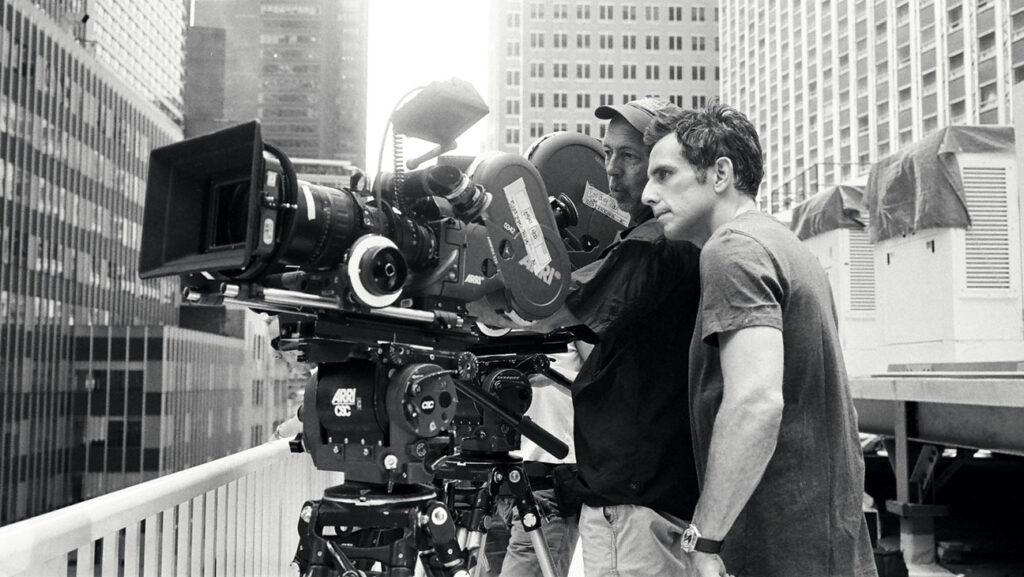

One of my favorite directors hops on a thought-provoking concept with shades of Charlie Kaufman!

Genre: Sci-Fi/Drama

Premise: After dying, a man is re-born into his life, reliving it from the start, unable to do anything but observe. Except for one difference – he saves a woman’s life who changes everything.

About: Did someone say that short stories are the new specs? Oh yeah, I SAID THAT. Cause these things sell like iced lemonade in Death Valley. And it’s not just horror stories. In this case, we’ve got a science-fiction short. This package came together when Ben Stiller signed on. The original story was published on Slate and was part of series of short stories about how technology and science will change our lives. The writer, David Iserson, has written on Mr. Robot, Mad Men, and New Girl.

Writer: David Iserson

Details: 4600 words (roughly one-fourth of a screenplay)

Link to short story: This, But Again

******************************************************

THE NEXT LOGLINE SHOWDOWN IS THIS FRIDAY, APRIL 21!!!!!

I will pick the five best loglines to compete on the site.

What: Title, Genre, Logline

Rules: Your script must be written

When: Send submissions by April 20th, Thursday, by 10PM pacific time

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

******************************************************

Okay, onto the review…

I’m always here for whatever Ben Stiller is up to.

He picks interesting subject matter as a director. From Severance to Escape at Dannemora to The Secret Life of Walter Mitty to Tropic Thunder. Whatever he does, I know I, at least, have to check it out.

Marcus dies in 2076 at the age of 87.

He wakes up in his mother’s womb. Marcus knew something like this would be coming because, back in the 2060s, scientists discovered that we were living in a simulation. Therefore, he knew that there was probably some sort of afterlife. Although he didn’t know it meant living your life over again.

Marcus quickly discovers that he’s an exception. Everybody else is ignorant to the fact that they’re reliving their lives. But because of some glitch in the code, Marcus is aware that he’s doing this again.

Unfortunately, he can’t change anything. He can only observe, like a passenger in a car. Which kind of sucks. Although it takes away a lot of anxiety and fear, since you already know what’s going to happen.

One day, in Life #2, he’s standing behind a girl, Sara, in college, at a street corner. In his previous life, Sara would voluntarily walk out into the road, get hit by a car, and die instantly. This time, however, Marcus uses every ounce of energy to do something to stop her. And he’s somehow able to utter, “Don’t.”

And she doesn’t. In this new life, Sara lives. Marcus had been obsessed with Sara from afar in college so he’d like nothing more than to get to know her. But, again, Marcus is a passenger. He can’t change things. The only time he’s able to change anything is when Sara speaks to him first. Then, he can override the autopilot and hang out with her.

They do end up re-meeting years later and, because Sara talks to him, they’re able to hang out together. This is when Marcus tells her what’s happening to him. She’s fascinated by this and wants to know more.

But, even though she likes being around Marcus, she grows frustrated. Marcus’s autopilot keeps taking him back to his original life. He ends up meeting his wife and also having two kids. So he and Sara can’t have a real relationship. They can only be together in fits and spurts.

Sara becomes obsessed with this concept of living a life without fear or anxiety. So she uses a video game coder to decode Marcus and becomes the announcer of the simulation a full 40 years before it was announced in Marcus’s previous lifetime.

Sara starts selling “Marcus” packages where people can live in their body already knowing what’s going to happen. Which a lot of people sign up for. However, as Sara gets older, and meeting with Marcus becomes harder, she questions what it is she wants out of life. Unlike everyone else, Sara is not reliving her life. She never made it past 20. This glitch ends up having a profound impact on her as she prepares for her next life.

Gimme a dramatic Jonah Hill for the part of Marcus!

I definitely see why Stiller signed onto this.

It’s a really weird and compelling story.

One of the best things about science-fiction is that it can change the perspective of otherwise common things so that they now appear new and fresh.

In This, But Again, we’re watching people live their lives and go through all the things they normally do but through a lens that makes it all feel very different.

Take Sara, for example. She wants love like everybody else.

But Sara was supposed to die at 20. That means everybody else in the simulation never ends up with her, as they all met someone else. They had to. Sara wasn’t around. So even though Sara’s around now, nobody can access her. Their autopilot won’t allow them to.

Meanwhile, Marcus wants nothing more than to be with Sara. But he can’t. His autopilot keeps taking him back to his other life.

Normally, all we’d have here is an average love story. We’ve read a million love stories so one more is going to be a bore-fest. But because of the unique circumstances surrounding these two, their love story feels unlike any other love story we’ve encountered.

Good old fashioned storytelling tools also help the story stand out. One of the best things you can do for your story is make things as hard as possible on your hero. Whatever it is they want, make it impossible for them to get. The more impossible it is, the more riveted the reader will be, since we’ll wonder how he’s going to overcome such a gigantic obstacle.

Nobody gets riveted when obstacles are easy. Cause we know that the hero will figure them out.

What’s more impossible than trying to be with someone when your body and mind literally won’t you let you? There’s a moment early in the story where Marcus and Sara go on a date to watch a movie together. And when Sara goes to the bathroom, Marcus’s autopilot takes over and he simply goes back home and rejoins his wife. How do you overcome that?

I’m curious how Stiller is going to film this because the best way to tell this story is exclusively through Marcus’s eyes. His attempts to break through the programming and be with Sara make for the best aspect of the story.

If we’re also covering Sara’s point-of-view in the movie, which we do here in the story, we’re not going to feel as much pain during the times when Sara gets away because we’re going to see Sara ourselves a scene later when we cut to her. One of the stronger components of the story is that desperation to keep Sara around and not having any control over it.

Plus, I’m not totally on board with Sara’s storyline. All the stuff about her creating a giant corporation around living a foreknowledged-life is thought-provoking but it feels like the wrong direction, going that big, since the rest of the story is so intimate. Not only that, but the intimate aspect of it works so well.

I thought this was a top-notch story, though. Beyond everything I just mentioned, there are so many themes here that resonate. We don’t need to be living in a simulation over and over again to feel like we’re on autopilot. We’re constantly in situations where we really want to do something yet some invisible hand prevents us from doing it. This short story showed me what that felt like in a different way. And the next time I want to do something but my mind won’t let me, maybe I’ll push a little harder to override it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m a big believer that short stories need highly memorable endings. A twist-ending is preferable. But you can also include an ending like this, which is intense and has a huge emotional impact. I say this for short movies as well, the reason being that THERE ARE SO MANY OF THEM. There are endless short stories and short films. So if you don’t leave the audience with your biggest punch, there’s a good chance they’ll forget you. This one definitely leaves you with a gut punch.

Genre: Supernatural/Thriller/Horror

Premise: When a retired war journalist returns to the outpost where her son was stationed to investigate the mysterious circumstances surrounding his death, she uncovers unspeakable horrors.

About: This finished in the middle of last year’s Black List. Peter Haig is a writer-director who, up until this point, has focused mainly on short films.

Writer: Peter Haig

Details: 111 pages

Bullock for Weaver?

Bullock for Weaver?

No, you are not experiencing deja vu.

I did review an almost identical script a couple of years ago, which was also on the Black List, called, “War Face.” The logline for that was: “A female U.S. Army Special Agent is sent to a remote, all-male outpost in Afghanistan to investigate accusations of war crimes. But when a series of mysterious events jeopardize her mission and the unit’s sanity, she must find the courage to survive something far more sinister.”

So what’s going on here?

That’s a good question. It’s something I’ve thought about a lot because the Black List is notorious for recycling identical script ideas. Sometimes these cloned concepts show up in the very same year.

My two leading theories are, one, none of us are as original as we think we are. We’re all pulling ideas from the same pot. And two, certain managers love certain subject matters and they’re pitching these ideas to their writers to write.

Which sort of makes sense. I love plane crash stories. So if I was a manager, I’d repeatedly encourage my writers to give me a plane crash script to pitch. And if you’re one of those writers, you’d seriously consider it because you’d know I’d push that script hard.

Whatever the phenomenon, it is weird how frequently it happens. The more conspiratorial side of me thinks there’s something deeper going on here. But every hypothesis I come up with sounds wackier than that infamous Shane Dawson conspiracy theory about how Chuck E. Cheese recycles their uneaten pizza.

A conspiratorial mindset is a good mindset to have going into this script because the story is all about weirdness and trying to figure out what’s going on.

Meet Mona Weaver, a 50-something war photographer heading out on her latest mission, joining up with the U.S. Army in Afghanistan to document an outpost for a couple of months.

Except that’s not what Weaver is really doing. Weaver’s son died out here in Afghanistan under mysterious circumstances and this is the outpost he died at. So Weaver’s being sneaky, pretending she’s documenting the army. But really she’s trying to figure out what happened to her son.

The team she’s with is made up of 18 year old Private Chang, who’s big and dumb, so everyone calls him Lennie (Of Mice and Men). We’ve got the hick of the group from Appalachia, Gibbs. We’ve got the doctor, Clemente. We’ve got the commander, Lieutenant Clay. All these dudes are half Weaver’s age. Which means she’s got to get them to trust her on two fronts (professionally and demographically).

They head out to a remote outpost and things immediately go bad. As they’re digging trenches, they collapse into a tunnel where a whole bunch of human bones are found. Nobody here likes this and thinks it’s a bad omen, which it definitely is.

In the first week, they’re attacked by crazed monkeys. But these monkeys don’t seem normal. They have a human quality to them. Then, one night, Chang is surveying the surroundings through his infrared goggles and spots a soldier coming towards him. But the soldier is dressed in 1900s military gear. And when he takes the infrared goggles off, he’s gone.

This starts to wear on the unit’s sanity but Weaver stays diligent. She’s determined to find out what happened to her son. His last known location was next to a strange-looking tree, which he sent his mom a picture of standing by. So that’s what Weaver is looking for. But when the commander learns what she’s up to, he does everything in his power to prevent Weaver from finding out what happened.

One thing I noticed right away here was the strong writing.

Too many times with these Black List scripts, they feel more like people trying to be writers than actually being writers. Note how visual Haig is when describing the story’s first base…

Concrete barriers, gates, watchtowers, bunkers, all in a ring of barbed wire. The substantial base sticks out like a Western sore thumb in the desert terrain of Wardak Province.

I love how we get these concrete visuals to latch onto. The barriers, the gates, the watchtowers, the bunkers, the barbed wire. Then he paints the bigger picture of what this base looks like compared to its surroundings. And he tops it off with some specificity. He doesn’t just give us a generic label. It’s “Wardak Province,” making it all feel specific and real.

Contrast this with his description of their outpost a dozen pages later:

The Outpost is so primitive it nearly defies comprehension — this can’t possibly be a base belonging to one of the most powerful armies in human history.

It looks more like third-world shantytown. A ramshackle village of tin sheds and plywood huts, all encased in sandbags and surrounded by angry, rusty, razor wire.

Again, we get the same attention to detail. I love that word “shantytown.” It puts a strong image in my head. That’s important when you’re writing about places the average person has never been. You need to find words that create powerful images. But I like how he didn’t stop there. We get the combo description of “angry, rusty, razor wire.” The average writer would’ve stopped at, “rusty wire” or “twisting wire.” The “angry” descriptor takes it up a notch. There’s something more visceral about it.

Through those first 30 pages, I felt like I was in good hands.

But the writing runs into some issues in its second act.

It’s important to note the distinction between good writing and good storytelling. Good writing is mainly in the description of things. The writer has a talent for describing characters, locations, and actions, in a way where we can effortlessly visualize them.

Storytelling is about the creative choices you make in a story. In Everything Everywhere All At Once, storytelling is the choice to create all these dimensions and figure out how those work and figure out how our characters access them. And then you come up with the goals for the characters and the obstacles they must overcome and how those goals create intersections between characters. If they both want the same thing, where do they clash and what results come of that clash?

Storytelling is the truly creative side of writing.

I struggled with the storytelling here. The script relied too heavily on “crazy stuff happens” moments. Monkey attacks, 1900s era soldiers, goats voluntarily committing suicide, characters going insane. I’m all for something crazy happening in a script. It can be fun. I just felt there was an over-reliance on it.

That focus on finding the next scare or shock prevented the writer from identifying a lack of fully fleshed out scene-writing. Scenes that have a beginning, a middle, and an end. Scenes that have a clear goal, someone standing in front of that goal, the conflict that resulted from that obstacle, and then a conclusion. Instead, we had an endless stream of scene fragments. It felt like every scene was 1 page long. I needed moments that breathed.

With that said, the script got the main part right, which was we cared about Weaver finding out what happened to her son. The opening nightmare she has, where she dreams of her son when he was still a little boy, showed us her grief in a devastating way.

But the back end of this script is so sloppy that I always felt like I was combing through it to find the meat. Like I had to use all my mental strength to dig through the muck to get to the heart of the story. It was too much, “Hey, what was that weird thing out there” and not enough carefully thought out moments that built up to a crescendo. And that, ultimately, stole a ‘worth the read’ from this script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: At a certain point, you just gotta tell us what’s going on. I read too many scripts where the writer talks around a character goal. They’ll ALLUDE to what the character is doing without ever explicitly telling us. That gets old fast when you’re the reader. Cause we just want to know what’s going on! Early on in Fog of War, we see Weaver obsessively looking at pictures of trees on her computer without any context. It creates a sense of mystery. Why is she doing this? But we only have to wait until page 20 to get our answer.

A POLAROID PHOTO of GAVIN DAVIDSON — full combat attire — standing by an peculiar looking KNOTTED HOLLY TREE.

Stubble on his face, in this POLAROID Gavin’s exhausted, wearing a vacant thousand yard stare — far from the lively persona captured in the bunk photo.

Written on the POLAROID’s film frame reads — The tree with the mark, we made in the bark, houses our treasure below.

Finally, this makes it clear that… Weaver is trying to find the knotted tree from the Polaroid.

You see that last part there? The writer straight up tells us what our hero is trying to do. I know we’re all terrified as screenwriters of being on the nose. But when it comes to the most important parts of your plot, don’t dick the reader around. Explicitly tell us what’s going on.

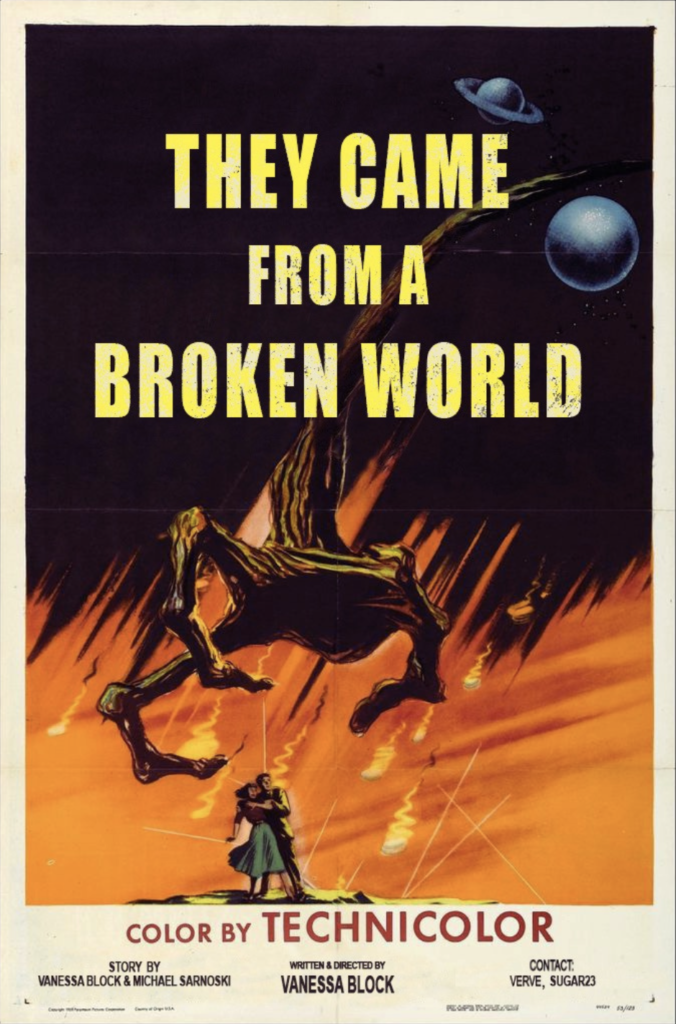

The writer of Pig gives us an intensely dramatic sci-fi tale

Genre: Drama/Sci-Fi

Premise: The year is 1955. The small town of Boon Falls has provided a local forest as refuge to aliens fleeing their war-torn planet. When Mia–young woman dealing with the trauma of her mother’s death–stumbles upon an Alien woman who needs her help, a series of haunting revelations in the refugee forest leads her to an unimaginable truth.

About: This script got a solid 14 votes on last year’s Black List. The writer has a significant credit to her name. She has a story by credit for the celebrated Nicholas Cage movie, “Pig.” If you’re wondering what a “story by” credit means, what it typically refers to is that a writer came up with the idea and wrote a script. Then another writer came around and rewrote the script enough that they got the main credit. The story by credit was created so that the original writer was always protected on a screenplay and got *some* credit. Especially since so many directors rewrite scripts and want the sole credit.

Writer: Vanessa Block

Details: 102 pages

First of all, cool poster title page. It feels professional.

Every once in a while, I run into one of these poster title pages and they’re almost always made by an overeager amateur writer who’s so excited about doing it himself that he’s unable to see how amateurish his poster looks. That mistake can cost you reads.

So, instead, go over to Fiverr.com. Search “movie poster artist” and I guarantee you you can get a better poster for probably less than 50 bucks.

It’s 1955. We’re in Boon Falls, Nowhere, USA. This tiny town is celebrating something called Heritage Day. It’s here where we meet 17 year old Mia, an African-American girl. Mia is a very unhappy individual. She’s always smoking. She has cuts on her legs from self-harm. She’s never in a good mood.

A lot of this stems from her dead mom, who she never really knew. But it also comes because of these aliens who live in the forest nearby. Years ago, aliens fleeing their world crash-landed on earth and the people of Boon Falls allow them to live in their nearby forest. If Mia had her way, these aliens would be outta here.

So it’s the shock of all shocks when, one evening at home, Mia discovers a hidden doorway in her house and follows it down to a basement where we learn that an alien girl was being kept by her mother. I think the mother was helping the alien stay alive but it’s kind of unclear.

Anyway, Mia finds this basement dwelling alien in the flesh and follows her into the forest. The alien eventually confronts her and explains that she’s trying to get to her ship where there’s still some of her peoples’ life water left. This red life-water allows her to both replenish as well as remember her past. So she’s very eager to get her hands on it.

When Mia’s father learns that Mia is with the alien, he calls the head guy in town, Arthur, who then sends drones after her. Since everything is a mystery wrapped in an enigma, we’re not sure why. But we hear something about how, under no circumstances can Mia find out the truth. What that truth ultimately is ends up answering all our questions and determines the fate of both Mia and our alien.

One of the hardest things about screenwriting – at least something it took me a long time to figure out – is that just because you feel something when you’re writing, it doesn’t mean the reader feels it as well.

So if you write this really sad scene where your main character watches their best friend die – writing that scene might make you cry. But if you didn’t do the legwork of making us like the friend character, making us root for the main character, crafting the scene in such a way that it maximizes the situation, identify a tone that’s not too intense and not too light, but right in that sweet spot, as well as a dozen other things — we’re not crying along with you.

In other words, inciting an emotional reaction from a reader takes skill and craft just as much as it takes an understanding of human emotion and social dynamics.

“They Came From A Broken World” is written to be a highly emotional experience. But I wasn’t invested enough to feel the same emotion as the writer.

This is at least partly because I’m not a fan of melodrama or monodrama. Melodrama is hitting a heavy emotional beat over and over again. Monodrama is when you only get one emotion – in this case, sadness. And we get it over and over again.

I need my stories to have levity. What’s great about levity is that it primes the reader to feel the emotions deeper. We can only truly feel happiness if we have sadness to balance it against.

I don’t think there was a single joke in this entire script. That’s unacceptable. Even for a drama. One of my favorite recent movies is Palm Trees and Power Lines. It’s a very dark movie. But it’s got laughs in it. It has joy in it. You need that joy so that your state can be taken to a place where the dark moments hit you harder. Dark moments don’t hit hard when you’re already in the dark.

This script has a decent story. There’s a mystery going on here and it’s a fairly interesting one. I definitely wanted to find out what happened. But without giving too much away, the mystery ends up being something we’ve seen before and which I pretty figured out early on. Whenever a writer is writing their story under so much fog and subterfuge – they’re not giving you anything at face value – I know they’re hiding something. So if they’re hiding something, a big twist is coming. If I know a big twist is coming, I can start trying to guess what. And since there are a finite number of twist scenarios for this setup, it wasn’t hard to figure out.

I also thought the script tried to do too much. We’ve got the illegal alien issue (some people in town hate the aliens). We’ve got climate change (people escaping a world that’s falling apart). We’ve got racism (the backstory alludes to discrimination in the 50s). We’ve got sexism (the aliens are all women). I’m not going to lie. At a certain point, it felt like a Black List bingo card.

Look, I get it. We’re all passionate about things. But a script isn’t about getting all of our philosophies and theories and ideologies into one place. Stories are much more powerful when they’re exploring a singular issue.

Which leaves They Came From A Broken World in the same category as a lot of the scripts from this year’s Black List: messy. Almost like the writers are figuring their story out on the page. Which is why this wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It’s hard to write a good script when the main character is a follower the whole movie. Mia is a follower. She’s following the Alien, who has the actual mission. To be fair, one of my favorite characters ever, Luke Skywalker, is a follower. But Lucas countered that by making Luke feisty and highly active in lots of moments. Mia is waiting to be led most of the movie and while it’s not a script-killer on its own, when combined with the other things I mentioned, it’s the poison cheery on top of the uh-oh sundae.

Today, I want to introduce you to a friend of mine, David Aaron Cohen. David’s been working as a writer in this business for 30 years. The two of us have bonded over our Chicago deep-dish roots and mutual love of tennis, specifically our fascination with the sport’s newest superstar, Carlos Alcaraz. David was able to see him live in Indian Wells a couple of weeks ago. I’m still jealous.

Recently, David told me about a class he’s been wanting to put together forever that focuses on teaching writers something that’s never taught: how to navigate the business side of the industry. We’re not talking about how to write a good logline or how to nail those first 10 pages. We’re talking about how to pitch, how to get an agent, how to sell to streamers, how TV writers rooms work, how to navigate a writing assignment when you’re dealing with four different producers – the kind of stuff we’ve all wished there was a class for. Well, now there finally is.

It’s going to be a 9 part Zoom course, each session being 2 hours long, and it’s definitely going to fill up fast. So you’ll want to register as soon as possible. Sign-up details will be at the bottom of the post.

For those of you who don’t know anything about David, he had a movie released last year called AMERICAN UNDERDOG (a 98% audience rating on RT), has two tv series in development – one with Sony, one with Lionsgate, just finished adapting the international best-seller, MAN’S SEARCH FOR MEANING. Going back deeper into his catalog, he co-wrote THE DEVIL’S OWN, starring Harrison Ford and Brad Pitt. He also wrote one of the great sports movies of all time, FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS.

In order to get a feel for David and what he’s like as a teacher, I asked him to share a few of the biggest lessons he’s learned in the business. But before we get to those, I demanded he tell me (and you) the craziest story he’s ever experienced as a screenwriter.

DAVID AARON COHEN: There have a been a few. LOL. Here’s one. 2017 I get a call from a director friend of mine. He’s been hired to make a 10 million dollar movie with John Travolta. Only catch is, we have to write a script for him to read and sign off on by February 5th. I look at the calendar. It’s January 14th. What the hell? We break the story in 5 days, card it, set our page counts, and work 21 days straight. Deliver it to the producer who gives off the worst vibes. Total hustler. But his check cleared.

Travolta reads and approves the screenplay. Casting happens: Katheryn Winnick, Tom Sizemore (one of his last roles). Pre-production. Shooting in Puerto Rico. I do some rewrites. Jodi, the director (not his real name!), heads off to the island. The day before principal photography starts, the line producer (who’s in cahoots with the shifty producer) announces that instead of the 5 million dollars left in the budget for shooting, there’s only 1.9 million. Have to cut 35% of the script. IN ONE DAY. You can imagine how that turned out. The producer literally STOLE the other 3 million dollars. Against all odds, Jodi kept shooting. Then a hurricane hit Puerto Rico and destroyed all the sets. I kid you not. Somehow, he finished the movie.

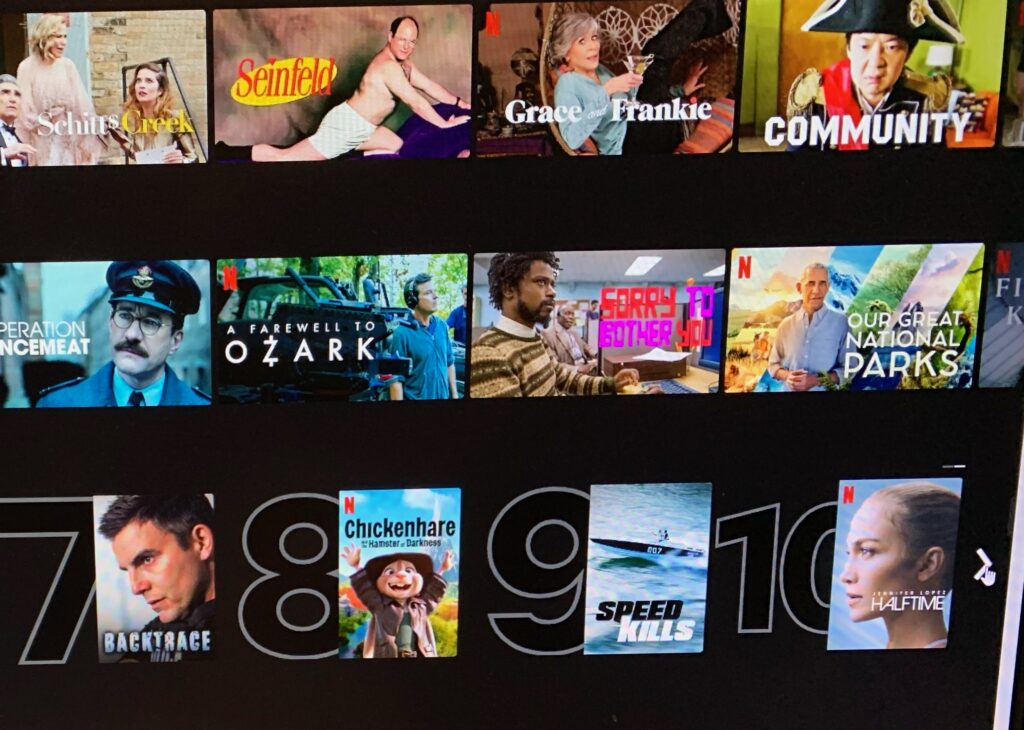

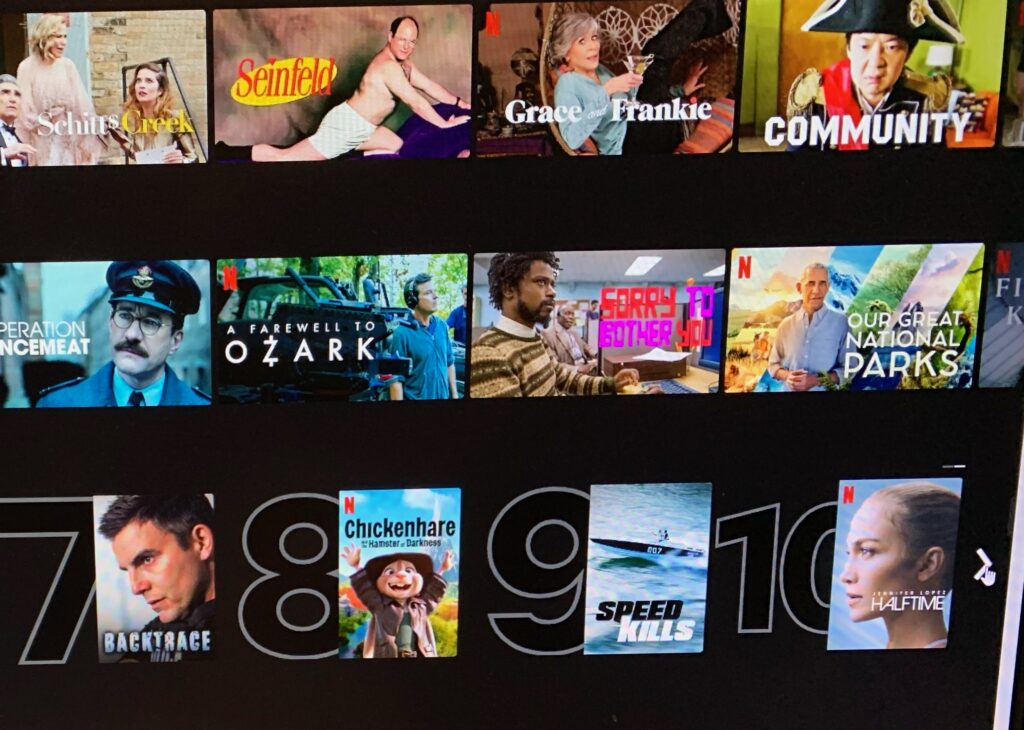

I saw bits of it back in L.A. We made a plan to do re-shoots with the contingency budget to make all the plot holes make sense. But the producer had STOLEN that money too. Then he fired the director. Edited the movie himself. Delivered it to the distribution company. I still haven’t gotten drunk enough yet to watch it, although I have read some of the audience reviews. They’re hilariously bad. But here’s the final plot twist. Last summer I log onto Netflix, looking to watch the new Adam Sandler movie HUSTLE, and I see this: “TOP TEN MOVIES STREAMING IN THE U.S.: NUMBER 9 – SPEED KILLS”

As someone once said, “there’s no accounting for taste.” Or chalk it up to a great poster.

CARSON: This is literally my worst nightmare! And yet, my Friday night viewing is set. Did you see what I did there? “Friday Night.” :) Okay, let’s jump into the lessons. Take it away, David!

*************************************************

DAVID: Thanks, Carson. I want to start by sharing an “Ah-Ha” moment from earlier in my career. It’s something I call…

MAKING MOONSHINE

This is a process critical to every story you ever want to tell. How do you make moonshine? Take your basic still out in the backwoods, fill it with mash. Heat that up with steam. The mash sinks to the bottom, but the vapors that rise are pure alcohol. That’s your job, making those vapors. When they condense back into liquid, you’re drinking moonshine. Which is a really convoluted way of saying, DISTILL YOUR STORY DOWN TO ITS ESSENCE. Distill! Distill! Distill! Put it into the pressure cooker of your heart and soul and guts until those vapors start to rise. All great stories start with essence.

Here’s one example. My big break in Hollywood was getting tapped by director Alan J. Pakula (ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN, SOPHIE’S CHOICE, KLUTE, etc.) to adapt a little-known non-fiction book called FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS. I wrote a first draft which everyone agreed got the tone right, but little else. I kept going. I was flailing around. Six months passed. The studio panicked and so did I, but Pakula didn’t. He pushed me to dig deeper, to find the essence of the story, to go find the core. We talked. We went back and forth. Is it the coach’s story? The quarterback’s? There was a lot of father/son energy. Maybe that was the key. But none of those ideas provided the throughline we were looking for – the central idea that was bigger than any individual character. Without that idea, all I had was mash.

What does it mean on a story level to heat up the mash? It means being curious. Fearless. Letting go of fixed ideas. And doing the research. I had spent a couple weeks in Odessa a year prior, meeting with the players who were on that 1988 Permian Panthers team. They were three years out of high school, but still haunted by their experience, by the feeling they had let everyone down. I could sense the heat there, when I put myself in their shoes, when I opened my writer’s self to what they were feeling.

I remember the moment it all crystallized. I was sitting in a little anteroom of Pakula’s New York City office, next to a pile of old luggage. And then this sentence kind of hit me, like a download. This is a story about a group of high school football players who carry the hopes and dreams of an entire town on their shoulders. That was it. Moonshine in twenty-five words. I sat down and wrote the draft that became the movie, guided by that idea. It poured out of me in like four weeks because I now knew what FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS was about. What every character was feeling. Go watch it. You’ll see that all the scenes serve that master, that controlling idea, that logline – call it whatever you want. I call it MAKING MOONSHINE.

PITCHING IN THE ZOOM AGE

One of the most critical skill sets you need to master to succeed in our business is the art of the pitch. Great stories CONNECT with people. When pitching, you are the CONNECTOR. Think of it like an electric circuit. The story is the current. You’re the switch. When you flip the switch, that story energy must ELECTRIFY your audience. And I’m not talking about reaching their heads. The jolt of your story has to hit them right in the gut. The solar plexus. First chakra. Does that sound hard? It should. Because it is. But if you’ve done your homework, if you’ve made your moonshine, you’re ready.

Back in the late 80’s when the whole “high concept comedy” idea was dominating Hollywood, I used to laugh and say the opposite is true. ‘High concept’ is just code for the stupidest, low-brow humor – the classic example back then being a five-word pitch: “DANNY DEVITO, ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER: TWINS!” But with 30 something years of pitching in the rear-view mirror, I look at that and see genius. It’s like the Michelangelo of Moonshine! Five words that conjure up an entire movie! Twelve syllables that give you that jolt, that laugh, that coin drop moment! You see the poster, the trailer, the whole thing. (FYI TWINS cost 15 million dollars to make in 1988 and grossed over 200 million worldwide.)

But the era of selling one-line pitches is long gone. In today’s marketplace you need to be ready to flip that switch and deliver the one-minute version, the five-minute version, the 15-minute version, and the (rare) 30 minute deep dive. Does that sound hard? It is and it isn’t.

The most important ingredient in a successful pitch is something everyone can deliver. It’s PASSION. Let me take you there. Imagine you just had the most earth-shaking experience of your life. You watched your wife give birth! You lived through an 8.0 earthquake! You were about to drown, and someone saved you! And now, minutes later, you are telling your best friend about it. How would you sound? Breathless, pumped, adrenaline flowing? That is pitch energy! That’s what you’ve got to bring.

Second ingredient: CLARITY. Your passion captures the attention of your audience. It delivers the jolt. Now you need to get in their heads. Not with an overload of information. Just enough to let them know where things are heading. Which is why a big piece of clarity is proper SIGNAGE. Lay out the story with that Carson-esque contest-winning logline, then post the signs that put the doubts to rest: act breaks, character arcs, key plot points. Give your audience the same feeling you get from reading the first pages of a great script. What happens there? You relax and settle in, knowing you are driving down the story highway in good hands.

Ingredient #3: EMOTIONAL LANGUAGE. Because there is a big catch to clarity. There is a ticking time bomb associated with delivering information. The minute it feels dry, perfunctory, logical or any of the above, your car just crashed off that highway. Every beat needs to be soaked in emotion. Cannot emphasize this enough. Your hero isn’t “heartbroken,” she’s CRUSHED. Your villain isn’t a “badass,” he’s KIM JONG-UN ON STEROIDS (Ok, you can probably do better than that). Movies are about emotion. They are about making your audience FEEL. Why are horror movies eternally popular? Because they target the one emotion that everyone can relate to: FEAR. Your pitch MUST BE an emotional experience. So pull out all the stops. Speed up, you slow down, your voice goes high and low. You pause at the moments of suspense. I know what a lot of you are thinking here: “I’m a writer. I’m not an actor.” Well, then go write the script of your pitch. Write it out word for word. Make it passionate, clear and full of emotional language on the page, and then…

Ingredient #4: PRACTICE THE HELL OUT OF IT. Pitch it to your friends. Pitch it to your parents. Pitch it to the postal worker. Get over yourself and your shyness. Pitch it to the mirror. Record it on video. Ask your actor friends for input. LISTEN TO WHAT THEY SAY. If you want to succeed in our highly competitive business, you better be ready to work outside your comfort zone.

And while selling a pitch is fantastic, it isn’t the only positive outcome of pitching. It’s your opportunity to leave a powerful impression on the people in the room. Trust me, they will remember a great pitch. That way, even if they don’t buy it, they are buying into you – your talent, your power to tell a great story. So the next time they’re looking for a writer for something that REMINDS them of you and your pitch, you’re already on their radar. Invited back for a meeting about that pitch-related job.

Here’s how this pays dividends. 2019. I’m out pitching a tv series. I’ve been developing this show over the course of MANY years (so many, I don’t even want to tell you. Okay. I pitched and sold it in 2014 to TNT. It languished. Didn’t go anywhere. Got the rights back. Started pitching it again). The meeting is at Lionsgate. There’s a new set of producers in the room. One of them hears my pitch for the first time. He’s so taken by it, he invites me out to dinner because he wants to pick my brains, to learn how to write and deliver a pitch exactly the way I did. At the end of the same dinner, he asks me if I would be interested in writing a script with him about a football player named Kurt Warner. Three years later (and in the middle of the pandemic, mind you) AMERICAN UNDERDOG is released on 3000 screens. So you never know. Every time you tell a story it is an opportunity on so many different levels, known, unknown and TBD.

At the American Underdog premiere.

At the American Underdog premiere.

THE GREATEST GIFTS ARE NEXT TO THE DEEPEST WOUNDS

This is more of a writing lesson, true for your own life and for your characters. The idea is simple. Where you have been hurt, abused, wounded, jilted or otherwise injured, you bank the intensity of those feelings. Speaking strictly as a writer – those experiences form your personal gold mine. (One of the reasons why heartbreak stories are so popular – no one ever forgets the burning hot emotion around lost or found first love). It follows that the deeper you feel, the better your writing will be. But there are other kinds of gifts located right next to those wounds.

Personal example. I grew up in a house, not unlike a lot of others, where the family rule was don’t say what you really feel. Or even what you actually want. Everything was indirect and convoluted. Here’s my mom (bless her soul) visiting my house at age 65.

That was my mother, telling me she’s hungry. Used to drive me completely crazy. But later that night, I’m putting my daughter to bed. She’s maybe 10 years old and has just spent a few days in the company of her grandmother. Lights are out. I tuck her in. She’s got a question.

I feel this wave of emotion rising in my chest.

My daughter, whose emotional intelligence is light years beyond mine, takes a beat and then says:

My daughter, whose emotional intelligence is light years beyond mine, takes a beat and then says:

I literally started to weep. But that’s not even the point! I realized, afterwards, that the gift my parents gave me, the gift that was located right next to the wound of being born into a household of people tiptoeing around the truth was: I KNEW HOW TO WRITE SUBTEXT. I could write the crap out of scenes where people say one thing but mean another. Which, as you all probably know, is the essence of good dialogue. My parents gifted me with one of the most important tools in a screenwriter’s arsenal. And I thank them for that every day.

I literally started to weep. But that’s not even the point! I realized, afterwards, that the gift my parents gave me, the gift that was located right next to the wound of being born into a household of people tiptoeing around the truth was: I KNEW HOW TO WRITE SUBTEXT. I could write the crap out of scenes where people say one thing but mean another. Which, as you all probably know, is the essence of good dialogue. My parents gifted me with one of the most important tools in a screenwriter’s arsenal. And I thank them for that every day.

So check your wounds. And see if there are gifts waiting for you to harvest. And when writing your characters, consider their own wounds and then, explore what their gifts might be. You’ll find a new depth to their authenticity.

START THINKING LIKE A PRODUCER NOW

We are back in the career guidance category. Let’s call this a cautionary tale. Start thinking like a producer now because I didn’t. I wasted years seeing myself only as a screenwriter. I thought – I’m going to work at my craft, work really hard, be the best damn writer I can be, and that should be enough. And it was enough, the first ten years of my professional career.

In 1995 Pakula called me to come work on THE DEVIL’S OWN, a film that was already in pre-production. Alan was directing. We had the two biggest movie stars in the world attached (Harrison Ford and Brad Pitt), one of the great all-time producers in Larry Gordon (FIELD OF DREAMS). And speaking of Gordons, Gordon Willis, the same guy who shot THE GODFATHER, was our DP! What could go wrong? Well, for one I was rewriting the screenplay from scratch, 60 days before the start of principal photography on a 90-million-dollar film. Larry knew it was an impossible task for a single writer, so he teamed me up with the incomparable Vincent Patrick (THE POPE OF GREENWICH VILLAGE).

Vince and I took a script by Kevin Jarre (essentially a story about an IRA terrorist who comes to New York and moves into the basement of an Irish New York City cop), and we turned it into a full-on two-hander. Why? In the original draft the character of Tom O’Meara is kind of a shlubby beat cop with two left feet. When Harrison came on board to play the part (and Sony agreed to his fee), Peter Guber, then president of the studio, famously said: “I’m not paying Harrison Ford 20 million dollars to drop his gun in the middle of a chase scene!” Hence the rewrite. Endless drama ensued, off-screen, not on. Pakula, Vince and I flew out to Harrison’s compound in Wyoming to talk story, then rode Harrison’s Learjet to LA to meet with Brad at the Four Seasons, and then back to New York. It was like shuttle diplomacy, only the arguments weren’t over international geopolitics. More like how many scenes does Brad get versus how many lines does Harrison have? In the end we delivered a script that we were proud of. And the movie kinda works. But I digress.

The point of all that was I was living a good life as a screenwriter. And being young (and stupid) I thought everything would just continue along the same path. I mean when you start flying on the Sony corporate jet to New York (four of us, one stewardess), and the studio puts you up in a four-story brownstone on the upper East side of Manhattan for $20,000 a month, you run the risk of getting spoiled. (Ah, the 90’s!) I got lazy and entitled and adopted the mindset of expecting jobs to come to me instead of creating them. What I should have done was to start looking for material that I liked and optioning it, or partnering with other producers on IP so that when we went out to sell, it would be my project, my package. There would never be a question who was going to write it.

Instead, I burned through precious time chasing the dreaded OWA’s (Open Writing Assignments). The biggest scam in Hollywood. A studio comes up with an idea. Not even fleshed out. (To quote Woody Allen from ANNIE HALL: “Right now it’s only a notion, but I think I can get money to make it into a concept… and later turn it into an idea.”) But seriously – then they post this idea as an OWA, get ten really talented writers to come in and pitch their take on turning this sow’s ear into a silk purse. Now creating a take like this requires the exact same amount of effort as breaking an original story. But you do it because you believe you will always have the best ideas in the room, and mainly because you’re thinking about the 300k they’re going to pay you to write it. Only problem is the studio is listening to TEN different takes, each of which took that individual writer weeks of hard work to come up with, and then when they choose the other writer who had an inside track on the gig because his or her agent is sleeping with the executive (just kidding! Not!), you are left with BUPKIS, nada, nothing. You don’t own it and you can’t use it because you did it all in service of their ridiculous non-concept.

Which leads me back to the main topic here: BE A PRODUCER. What does that even mean? First (apropos the key ingredient for pitching), go where your PASSION is. Chances are you are already dialed in to certain worlds that you care about. That’s where you’re going to do the best digging. Case in point: I’m a sports fan. Nobody has to remind me to read articles about the Lakers or to watch the Bears games (Carson and I both hail from Chicago and root for the Bears, which is kind of like being members of the same 12 Step Program!). I’ve made a love of sports part of my brand. So in 2020 when the pandemic was raging, I spent even more time scrolling around ESPN.COM. Found myself on this ESPN+ women-in-sports page where there was a video posted about a Paralympic athlete named Oksana Masters. I clicked. It was like seven or eight minutes long, told her story. Childhood in Ukraine, in an orphanage. Being adopted by a single American mom. Footage of Oksana skiing. It wasn’t really that remarkable, when I think about it. But there was something that drew me in, that inexplicable thread that you can’t help but tug… so I tugged.

I ended up on her website. And there was this quote on the masthead that said: “Success, for me, is an everlasting pursuit of that which scares me the most. That’s the place I truly live.” And I thought to myself… THAT IS A STORY. I hunted her down. Got in touch with her sports agent. And then we met, like everyone else during the pandemic, on zoom. We made a connection. And kept talking and talking. And the more of her story I heard, the more convinced I was that it was a viable feature.

Fast forward, it’s two and a half years later. I brought an amazing director on board, who I met because I read an article about her in the LA Times. Sent her an email – the equivalent of a cold call. She answered. Fell in love with Oksana’s story. Turned out they had a shared history of disability, of going through some of the same surgeries when they were both young girls. The director and I bonded, then we wrote a pitch together, honed it, beta-tested it, kept making changes. And now we are out pitching it, in the spirit of CODA meets PERKS OF BEING A WALLFLOWER. I am confident we will set it up.

But the point here is ALL OF THIS IS PRODUCING. Identifying great material that lives in your personal wheelhouse. Going after it. Building relationships. DOING THE LEGWORK! How much money did I have to spend to get the rights to Oksana’s story? I didn’t. I INVESTED in her instead. I spent hours with her on zoom because it mattered to me. Because I saw the potential for telling a story that has never been told before – this fascinating world of elite Paralympic athletes, who make huge sacrifices to be the best in the world at their given sport. The reward is when I go out to pitch the project now, I don’t have to worry about who is going to write it. Or who is going to replace me if I get the gig and the producers are unhappy with my draft. Or who is going to direct it. I am the producer, and the writer. I earned my seat at the table. (And as a bonus, I’ll make more money when the movie gets made.)

All of you have this capacity to discover stories you fall in love with, and to bring them, successfully, to the marketplace. The sooner you start producing, the better.

*************************************************

CARSON: David’s course will run for nine straight Wednesdays (7-9 pm PST) starting April 26th. Some of the topics he will cover include: breaking into the business, pitching, agents & managers, selling to streamers, acing the development process, navigating writer’s rooms, and much much more. This is a live class, so you’ll have full access, including Q&A time, to learn about the business from a real pro. He will also be bringing in some cool guest speakers to take you deeper into their areas of expertise. Anyone who signs up through Scriptshadow will get a $300 discount on the course. All you have to do is mention the site or enter the coupon code SCRIPTSHADOW300 when you check out.

This course is for intermediate writers, writers on the cusp of breaking in, writers who’ve recently secured representation, and writers who have just entered the professional ranks. David has seen every situation in the book and he wants to make sure the next generation of screenwriters don’t fall into the same pitfalls he did. To register, get information on pricing, or to learn more, visit the course website at navigatinghollywood.net. Nobody’s ever taught a class like this so it’s going to fill up fast. There are a limited number of spots available. Register now!

Today, I want to introduce you to a friend of mine, David Aaron Cohen. David’s been working as a writer in this business for 30 years. The two of us have bonded over our Chicago deep-dish roots and mutual love of tennis, specifically our fascination with the sport’s newest superstar, Carlos Alcaraz. David was able to see him live in Indian Wells a couple of weeks ago. I’m still jealous.

Recently, David told me about a class he’s been wanting to put together forever that focuses on teaching writers something that’s never taught: how to navigate the business side of the industry. We’re not talking about how to write a good logline or how to nail those first 10 pages. We’re talking about how to pitch, how to get an agent, how to sell to streamers, how TV writers rooms work, how to navigate a writing assignment when you’re dealing with four different producers – the kind of stuff we’ve all wished there was a class for. Well, now there finally is.

It’s going to be a 9 part Zoom course, each session being 2 hours long, and it’s definitely going to fill up fast. So you’ll want to register as soon as possible. Sign-up details will be at the bottom of the post.

For those of you who don’t know anything about David, he had a movie released last year called AMERICAN UNDERDOG (a 98% audience rating on RT), has two tv series in development – one with Sony, one with Lionsgate, just finished adapting the international best-seller, MAN’S SEARCH FOR MEANING. Going back deeper into his catalog, he co-wrote THE DEVIL’S OWN, starring Harrison Ford and Brad Pitt. He also wrote one of the great sports movies of all time, FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS.

In order to get a feel for David and what he’s like as a teacher, I asked him to share a few of the biggest lessons he’s learned in the business. But before we get to those, I demanded he tell me (and you) the craziest story he’s ever experienced as a screenwriter.

DAVID AARON COHEN: There have a been a few. LOL. Here’s one. 2017 I get a call from a director friend of mine. He’s been hired to make a 10 million dollar movie with John Travolta. Only catch is, we have to write a script for him to read and sign off on by February 5th. I look at the calendar. It’s January 14th. What the hell? We break the story in 5 days, card it, set our page counts, and work 21 days straight. Deliver it to the producer who gives off the worst vibes. Total hustler. But his check cleared.

Travolta reads and approves the screenplay. Casting happens: Katheryn Winnick, Tom Sizemore (one of his last roles). Pre-production. Shooting in Puerto Rico. I do some rewrites. Jodi, the director (not his real name!), heads off to the island. The day before principal photography starts, the line producer (who’s in cahoots with the shifty producer) announces that instead of the 5 million dollars left in the budget for shooting, there’s only 1.9 million. Have to cut 35% of the script. IN ONE DAY. You can imagine how that turned out. The producer literally STOLE the other 3 million dollars. Against all odds, Jodi kept shooting. Then a hurricane hit Puerto Rico and destroyed all the sets. I kid you not. Somehow, he finished the movie.

I saw bits of it back in L.A. We made a plan to do re-shoots with the contingency budget to make all the plot holes make sense. But the producer had STOLEN that money too. Then he fired the director. Edited the movie himself. Delivered it to the distribution company. I still haven’t gotten drunk enough yet to watch it, although I have read some of the audience reviews. They’re hilariously bad. But here’s the final plot twist. Last summer I log onto Netflix, looking to watch the new Adam Sandler movie HUSTLE, and I see this: “TOP TEN MOVIES STREAMING IN THE U.S.: NUMBER 9 – SPEED KILLS”

As someone once said, “there’s no accounting for taste.” Or chalk it up to a great poster.

CARSON: This is literally my worst nightmare! And yet, my Friday night viewing is set. Did you see what I did there? “Friday Night.” :) Okay, let’s jump into the lessons. Take it away, David!

*************************************************

DAVID: Thanks, Carson. I want to start by sharing an “Ah-Ha” moment from earlier in my career. It’s something I call…

MAKING MOONSHINE

This is a process critical to every story you ever want to tell. How do you make moonshine? Take your basic still out in the backwoods, fill it with mash. Heat that up with steam. The mash sinks to the bottom, but the vapors that rise are pure alcohol. That’s your job, making those vapors. When they condense back into liquid, you’re drinking moonshine. Which is a really convoluted way of saying, DISTILL YOUR STORY DOWN TO ITS ESSENCE. Distill! Distill! Distill! Put it into the pressure cooker of your heart and soul and guts until those vapors start to rise. All great stories start with essence.

Here’s one example. My big break in Hollywood was getting tapped by director Alan J. Pakula (ALL THE PRESIDENT’S MEN, SOPHIE’S CHOICE, KLUTE, etc.) to adapt a little-known non-fiction book called FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS. I wrote a first draft which everyone agreed got the tone right, but little else. I kept going. I was flailing around. Six months passed. The studio panicked and so did I, but Pakula didn’t. He pushed me to dig deeper, to find the essence of the story, to go find the core. We talked. We went back and forth. Is it the coach’s story? The quarterback’s? There was a lot of father/son energy. Maybe that was the key. But none of those ideas provided the throughline we were looking for – the central idea that was bigger than any individual character. Without that idea, all I had was mash.

What does it mean on a story level to heat up the mash? It means being curious. Fearless. Letting go of fixed ideas. And doing the research. I had spent a couple weeks in Odessa a year prior, meeting with the players who were on that 1988 Permian Panthers team. They were three years out of high school, but still haunted by their experience, by the feeling they had let everyone down. I could sense the heat there, when I put myself in their shoes, when I opened my writer’s self to what they were feeling.

I remember the moment it all crystallized. I was sitting in a little anteroom of Pakula’s New York City office, next to a pile of old luggage. And then this sentence kind of hit me, like a download. This is a story about a group of high school football players who carry the hopes and dreams of an entire town on their shoulders. That was it. Moonshine in twenty-five words. I sat down and wrote the draft that became the movie, guided by that idea. It poured out of me in like four weeks because I now knew what FRIDAY NIGHT LIGHTS was about. What every character was feeling. Go watch it. You’ll see that all the scenes serve that master, that controlling idea, that logline – call it whatever you want. I call it MAKING MOONSHINE.

PITCHING IN THE ZOOM AGE

One of the most critical skill sets you need to master to succeed in our business is the art of the pitch. Great stories CONNECT with people. When pitching, you are the CONNECTOR. Think of it like an electric circuit. The story is the current. You’re the switch. When you flip the switch, that story energy must ELECTRIFY your audience. And I’m not talking about reaching their heads. The jolt of your story has to hit them right in the gut. The solar plexus. First chakra. Does that sound hard? It should. Because it is. But if you’ve done your homework, if you’ve made your moonshine, you’re ready.

Back in the late 80’s when the whole “high concept comedy” idea was dominating Hollywood, I used to laugh and say the opposite is true. ‘High concept’ is just code for the stupidest, low-brow humor – the classic example back then being a five-word pitch: “DANNY DEVITO, ARNOLD SCHWARZENEGGER: TWINS!” But with 30 something years of pitching in the rear-view mirror, I look at that and see genius. It’s like the Michelangelo of Moonshine! Five words that conjure up an entire movie! Twelve syllables that give you that jolt, that laugh, that coin drop moment! You see the poster, the trailer, the whole thing. (FYI TWINS cost 15 million dollars to make in 1988 and grossed over 200 million worldwide.)

But the era of selling one-line pitches is long gone. In today’s marketplace you need to be ready to flip that switch and deliver the one-minute version, the five-minute version, the 15-minute version, and the (rare) 30 minute deep dive. Does that sound hard? It is and it isn’t.

The most important ingredient in a successful pitch is something everyone can deliver. It’s PASSION. Let me take you there. Imagine you just had the most earth-shaking experience of your life. You watched your wife give birth! You lived through an 8.0 earthquake! You were about to drown, and someone saved you! And now, minutes later, you are telling your best friend about it. How would you sound? Breathless, pumped, adrenaline flowing? That is pitch energy! That’s what you’ve got to bring.

Second ingredient: CLARITY. Your passion captures the attention of your audience. It delivers the jolt. Now you need to get in their heads. Not with an overload of information. Just enough to let them know where things are heading. Which is why a big piece of clarity is proper SIGNAGE. Lay out the story with that Carson-esque contest-winning logline, then post the signs that put the doubts to rest: act breaks, character arcs, key plot points. Give your audience the same feeling you get from reading the first pages of a great script. What happens there? You relax and settle in, knowing you are driving down the story highway in good hands.

Ingredient #3: EMOTIONAL LANGUAGE. Because there is a big catch to clarity. There is a ticking time bomb associated with delivering information. The minute it feels dry, perfunctory, logical or any of the above, your car just crashed off that highway. Every beat needs to be soaked in emotion. Cannot emphasize this enough. Your hero isn’t “heartbroken,” she’s CRUSHED. Your villain isn’t a “badass,” he’s KIM JONG-UN ON STEROIDS (Ok, you can probably do better than that). Movies are about emotion. They are about making your audience FEEL. Why are horror movies eternally popular? Because they target the one emotion that everyone can relate to: FEAR. Your pitch MUST BE an emotional experience. So pull out all the stops. Speed up, you slow down, your voice goes high and low. You pause at the moments of suspense. I know what a lot of you are thinking here: “I’m a writer. I’m not an actor.” Well, then go write the script of your pitch. Write it out word for word. Make it passionate, clear and full of emotional language on the page, and then…

Ingredient #4: PRACTICE THE HELL OUT OF IT. Pitch it to your friends. Pitch it to your parents. Pitch it to the postal worker. Get over yourself and your shyness. Pitch it to the mirror. Record it on video. Ask your actor friends for input. LISTEN TO WHAT THEY SAY. If you want to succeed in our highly competitive business, you better be ready to work outside your comfort zone.

And while selling a pitch is fantastic, it isn’t the only positive outcome of pitching. It’s your opportunity to leave a powerful impression on the people in the room. Trust me, they will remember a great pitch. That way, even if they don’t buy it, they are buying into you – your talent, your power to tell a great story. So the next time they’re looking for a writer for something that REMINDS them of you and your pitch, you’re already on their radar. Invited back for a meeting about that pitch-related job.

Here’s how this pays dividends. 2019. I’m out pitching a tv series. I’ve been developing this show over the course of MANY years (so many, I don’t even want to tell you. Okay. I pitched and sold it in 2014 to TNT. It languished. Didn’t go anywhere. Got the rights back. Started pitching it again). The meeting is at Lionsgate. There’s a new set of producers in the room. One of them hears my pitch for the first time. He’s so taken by it, he invites me out to dinner because he wants to pick my brains, to learn how to write and deliver a pitch exactly the way I did. At the end of the same dinner, he asks me if I would be interested in writing a script with him about a football player named Kurt Warner. Three years later (and in the middle of the pandemic, mind you) AMERICAN UNDERDOG is released on 3000 screens. So you never know. Every time you tell a story it is an opportunity on so many different levels, known, unknown and TBD.

At the American Underdog premiere.

At the American Underdog premiere.

THE GREATEST GIFTS ARE NEXT TO THE DEEPEST WOUNDS

This is more of a writing lesson, true for your own life and for your characters. The idea is simple. Where you have been hurt, abused, wounded, jilted or otherwise injured, you bank the intensity of those feelings. Speaking strictly as a writer – those experiences form your personal gold mine. (One of the reasons why heartbreak stories are so popular – no one ever forgets the burning hot emotion around lost or found first love). It follows that the deeper you feel, the better your writing will be. But there are other kinds of gifts located right next to those wounds.

Personal example. I grew up in a house, not unlike a lot of others, where the family rule was don’t say what you really feel. Or even what you actually want. Everything was indirect and convoluted. Here’s my mom (bless her soul) visiting my house at age 65.

That was my mother, telling me she’s hungry. Used to drive me completely crazy. But later that night, I’m putting my daughter to bed. She’s maybe 10 years old and has just spent a few days in the company of her grandmother. Lights are out. I tuck her in. She’s got a question.

I feel this wave of emotion rising in my chest.

My daughter, whose emotional intelligence is light years beyond mine, takes a beat and then says:

My daughter, whose emotional intelligence is light years beyond mine, takes a beat and then says:

I literally started to weep. But that’s not even the point! I realized, afterwards, that the gift my parents gave me, the gift that was located right next to the wound of being born into a household of people tiptoeing around the truth was: I KNEW HOW TO WRITE SUBTEXT. I could write the crap out of scenes where people say one thing but mean another. Which, as you all probably know, is the essence of good dialogue. My parents gifted me with one of the most important tools in a screenwriter’s arsenal. And I thank them for that every day.

I literally started to weep. But that’s not even the point! I realized, afterwards, that the gift my parents gave me, the gift that was located right next to the wound of being born into a household of people tiptoeing around the truth was: I KNEW HOW TO WRITE SUBTEXT. I could write the crap out of scenes where people say one thing but mean another. Which, as you all probably know, is the essence of good dialogue. My parents gifted me with one of the most important tools in a screenwriter’s arsenal. And I thank them for that every day.

So check your wounds. And see if there are gifts waiting for you to harvest. And when writing your characters, consider their own wounds and then, explore what their gifts might be. You’ll find a new depth to their authenticity.

START THINKING LIKE A PRODUCER NOW

We are back in the career guidance category. Let’s call this a cautionary tale. Start thinking like a producer now because I didn’t. I wasted years seeing myself only as a screenwriter. I thought – I’m going to work at my craft, work really hard, be the best damn writer I can be, and that should be enough. And it was enough, the first ten years of my professional career.

In 1995 Pakula called me to come work on THE DEVIL’S OWN, a film that was already in pre-production. Alan was directing. We had the two biggest movie stars in the world attached (Harrison Ford and Brad Pitt), one of the great all-time producers in Larry Gordon (FIELD OF DREAMS). And speaking of Gordons, Gordon Willis, the same guy who shot THE GODFATHER, was our DP! What could go wrong? Well, for one I was rewriting the screenplay from scratch, 60 days before the start of principal photography on a 90-million-dollar film. Larry knew it was an impossible task for a single writer, so he teamed me up with the incomparable Vincent Patrick (THE POPE OF GREENWICH VILLAGE).

Vince and I took a script by Kevin Jarre (essentially a story about an IRA terrorist who comes to New York and moves into the basement of an Irish New York City cop), and we turned it into a full-on two-hander. Why? In the original draft the character of Tom O’Meara is kind of a shlubby beat cop with two left feet. When Harrison came on board to play the part (and Sony agreed to his fee), Peter Guber, then president of the studio, famously said: “I’m not paying Harrison Ford 20 million dollars to drop his gun in the middle of a chase scene!” Hence the rewrite. Endless drama ensued, off-screen, not on. Pakula, Vince and I flew out to Harrison’s compound in Wyoming to talk story, then rode Harrison’s Learjet to LA to meet with Brad at the Four Seasons, and then back to New York. It was like shuttle diplomacy, only the arguments weren’t over international geopolitics. More like how many scenes does Brad get versus how many lines does Harrison have? In the end we delivered a script that we were proud of. And the movie kinda works. But I digress.

The point of all that was I was living a good life as a screenwriter. And being young (and stupid) I thought everything would just continue along the same path. I mean when you start flying on the Sony corporate jet to New York (four of us, one stewardess), and the studio puts you up in a four-story brownstone on the upper East side of Manhattan for $20,000 a month, you run the risk of getting spoiled. (Ah, the 90’s!) I got lazy and entitled and adopted the mindset of expecting jobs to come to me instead of creating them. What I should have done was to start looking for material that I liked and optioning it, or partnering with other producers on IP so that when we went out to sell, it would be my project, my package. There would never be a question who was going to write it.

Instead, I burned through precious time chasing the dreaded OWA’s (Open Writing Assignments). The biggest scam in Hollywood. A studio comes up with an idea. Not even fleshed out. (To quote Woody Allen from ANNIE HALL: “Right now it’s only a notion, but I think I can get money to make it into a concept… and later turn it into an idea.”) But seriously – then they post this idea as an OWA, get ten really talented writers to come in and pitch their take on turning this sow’s ear into a silk purse. Now creating a take like this requires the exact same amount of effort as breaking an original story. But you do it because you believe you will always have the best ideas in the room, and mainly because you’re thinking about the 300k they’re going to pay you to write it. Only problem is the studio is listening to TEN different takes, each of which took that individual writer weeks of hard work to come up with, and then when they choose the other writer who had an inside track on the gig because his or her agent is sleeping with the executive (just kidding! Not!), you are left with BUPKIS, nada, nothing. You don’t own it and you can’t use it because you did it all in service of their ridiculous non-concept.

Which leads me back to the main topic here: BE A PRODUCER. What does that even mean? First (apropos the key ingredient for pitching), go where your PASSION is. Chances are you are already dialed in to certain worlds that you care about. That’s where you’re going to do the best digging. Case in point: I’m a sports fan. Nobody has to remind me to read articles about the Lakers or to watch the Bears games (Carson and I both hail from Chicago and root for the Bears, which is kind of like being members of the same 12 Step Program!). I’ve made a love of sports part of my brand. So in 2020 when the pandemic was raging, I spent even more time scrolling around ESPN.COM. Found myself on this ESPN+ women-in-sports page where there was a video posted about a Paralympic athlete named Oksana Masters. I clicked. It was like seven or eight minutes long, told her story. Childhood in Ukraine, in an orphanage. Being adopted by a single American mom. Footage of Oksana skiing. It wasn’t really that remarkable, when I think about it. But there was something that drew me in, that inexplicable thread that you can’t help but tug… so I tugged.

I ended up on her website. And there was this quote on the masthead that said: “Success, for me, is an everlasting pursuit of that which scares me the most. That’s the place I truly live.” And I thought to myself… THAT IS A STORY. I hunted her down. Got in touch with her sports agent. And then we met, like everyone else during the pandemic, on zoom. We made a connection. And kept talking and talking. And the more of her story I heard, the more convinced I was that it was a viable feature.

Fast forward, it’s two and a half years later. I brought an amazing director on board, who I met because I read an article about her in the LA Times. Sent her an email – the equivalent of a cold call. She answered. Fell in love with Oksana’s story. Turned out they had a shared history of disability, of going through some of the same surgeries when they were both young girls. The director and I bonded, then we wrote a pitch together, honed it, beta-tested it, kept making changes. And now we are out pitching it, in the spirit of CODA meets PERKS OF BEING A WALLFLOWER. I am confident we will set it up.

But the point here is ALL OF THIS IS PRODUCING. Identifying great material that lives in your personal wheelhouse. Going after it. Building relationships. DOING THE LEGWORK! How much money did I have to spend to get the rights to Oksana’s story? I didn’t. I INVESTED in her instead. I spent hours with her on zoom because it mattered to me. Because I saw the potential for telling a story that has never been told before – this fascinating world of elite Paralympic athletes, who make huge sacrifices to be the best in the world at their given sport. The reward is when I go out to pitch the project now, I don’t have to worry about who is going to write it. Or who is going to replace me if I get the gig and the producers are unhappy with my draft. Or who is going to direct it. I am the producer, and the writer. I earned my seat at the table. (And as a bonus, I’ll make more money when the movie gets made.)

All of you have this capacity to discover stories you fall in love with, and to bring them, successfully, to the marketplace. The sooner you start producing, the better.

*************************************************

CARSON: David’s course will run for nine straight Wednesdays (7-9 pm PST) starting April 26th. Some of the topics he will cover include: breaking into the business, pitching, agents & managers, selling to streamers, acing the development process, navigating writer’s rooms, and much much more. This is a live class, so you’ll have full access, including Q&A time, to learn about the business from a real pro. He will also be bringing in some cool guest speakers to take you deeper into their areas of expertise.

This course is for intermediate writers, writers on the cusp of breaking in, writers who’ve recently secured representation, and writers who have just entered the professional ranks. David has seen every situation in the book and he wants to make sure the next generation of screenwriters don’t fall into the same pitfalls he did. To register, get information on pricing, or to learn more, visit the course website at navigatinghollywood.net. Nobody’s ever taught a class like this so it’s going to fill up fast. There are a limited number of spots available. Register now!