Search Results for: F word

Genre: Sports Drama

Premise: A boxer’s life spirals out of control when his wife is killed, forcing him to team up with an alcoholic low-level trainer to make it back to the top.

About: “Southpaw” was written by Sons of Anarchy creator and all around badass, Kurt Sutter. Sutter got his break in Hollywood writing for the hit FX show, The Shield. What a lot of people don’t know is that Sutter is married to Peggy Bundy herself, Katey Sagal. Southpaw is Sutter’s first foray into features. This one’s got Jake Gyllenhall in the lead role, Rachel McAdams playing the wife, and Antoine Fuqua directing. Forest Whitaker will be playing the Oscar-friendly role of “Tick.” This is an older draft, written back in 2011. Believe it or not, the project has been around long enough where Eminem was once attached as the lead.

Writer: Kurt Sutter

Details: 122 pages – 3/9/11 Studio Draft 1 (keep in mind that a studio draft does not mean a first draft of the script itself, but rather the first draft the writer turned into the studio. A writer may have gone through many drafts of the script before turning it into the studio. Studio 1st Drafts are typically the drafts that most reflect the writer’s vision, as it’s before the writer gets studio notes).

Today’s script is like the anti-Brian Duffield. Kurt Sutter writes thick. Like the very first paragraph in Southpaw is nine lines. Duffield’s written entire first acts in nine lines. Now a lot of you point this out when you see it in scripts and say, “Carrssssonnn! How come THEY can write so much text and we have to keep everything to three lines or less??”

Basically, when you’re already in the industry and have fans of your writing, those people are going to read your scripts regardless of if they’re chunky or lean. But if you’re not yet in the industry, the reader will have less patience with you. They have what I call “bail mentality.” They’re ready to bail at any sign of difficulty. So you have to speed things along and get to the good stuff quicker in order to keep their attention.

33 year-old Billy “The Great” Hope is the best boxer in the world. He’s Mike Tyson in his prime. He’s got Lamborghinis, mansions, pools, he even has a beautiful wife (Maureen) and daughter (Leila). Hope seemingly has the world in his hands.

Then one day, Billy’s posse runs into the posse of Miguel “Magic” Canto, the younger quicker version of himself. Trash talk turns into threats and, in an instant, guns come out on both sides. (SPOILER) Shots are fired, and when everyone does a body check, it turns out Billy’s wife loses. She dies right there in his arms.

Billy spirals into depression, ignoring bills and contracts, even spacing out in the middle of fights. Over the course of half a year, he loses everything, even his daughter, after the local child services deem Billy unstable.

Billy can handle not having money. But he can’t handle life without his daughter. So he hires a low-rent one-eyed trainer named Titus “Tick” Wills to get him to a point where he’s making money again.

Tick tells Billy if he’s going to train him, he has to play by his rules. And that means dropping this bulldozer mentality he takes into the ring and learning how to actually BOX.

To improve Billy’s speed, Tick puts Billy in the ring with 15 year olds who are twice as fast as him, like little mosquitos. Then he teaches Billy how to break down his opponent with his mind. Learn their weaknesses so he can exploit them.

Resistant at first, Billy soon becomes a Tick disciple, and gets a bout with the man who’s responsible for his wife’s death. Will he win? Will he get his daughter back? Check out Southpaw to find out.

Because of Rocky, you can’t set up the ideal character scenario for a boxing movie anymore. Which is the down-on-his-luck underdog. No matter how you spin it, if you start your boxing movie that way, people are going to say you’re copying Rocky.

So you have to find fresh takes for your boxing hero. Sutter does this by introducing us to Billy at the top. An interesting choice, because that means he’s the opposite of an underdog. He’s a champion. And as I’ve stated here before, it’s damn hard to make the non-underdog sports story work.

But eventually, Billy hits rock bottom and BECOMES the underdog. Or does he? This was my only big issue with Southpaw. It wants to paint Billy as having no chance against Miguel “Magic” Canto. But we’ve already seen Billy pummel people into ground beef. So it’s a hard sell. And it’s not like Billy had an injury, something that made him slower. He’s the exact same guy.

Luckily, that’s not a deal breaker in these movies. With any fighting movie, it’s more about what happens OFF the mat than ON it. And we have three key relationships doing the work off the mat. We have Billy and his relationship with his daughter. Billy and his relationship with Tick. And Billy and his relationship with Angela, Billy’s daughter’s childcare worker.

I’ve said this before. Having three key relationships to explore in a script is an ideal number. If you go for more than that, you might not have enough time to properly explore each of those relationships (though it’s possible if your plot isn’t too heavy).

Southpaw’s success was always going to hinge on the relationship between Billy and Tick. And it’s pretty good. It’s not Rocky and Mick good, but there’s always an undercurrent of tension between them that keeps their interactions interesting. Plus Tick is a mysterious guy who we want to know more about (make characters mystery boxes, folks!). His backstory for how he ended up this way is one of the better backstories I’ve read in a sports movie. (good mystery payoffs earn you double points, folks!)

As for the daughter relationship, it was pretty good as well. The two didn’t have any issue to deal with. But remember, you don’t always need an issue. As long as there’s conflict SURROUNDING THE RELATIONSHIP in SOME CAPACITY, the relationship between two characters can be great. In this case, the conflict is the court – which is keeping Billy and his daughter apart.

Billy and Angela (the childcare worker) was the final relationship. And I could tell it was a tough one for Sutter. You can’t turn Angela into a romantic interest on the heels of his wife’s death. So that puts you in a spot that Hollywood movies are never comfortable with – putting an attractive male and female in a bunch of scenes together, and not exploring any romance.

But here’s how I would’ve dealt with it. And I’m far from a Sutter-caliber writer so you’re welcome to laugh me off. It wouldn’t be the first time. But it’s important to remember that every key character in your story should have a dilemma. Characters should never exist solely to serve the main character’s plight, but rather their own plight.

Angela is introduced as a stickler for the rules. She has to chaperone all visits between Billy and his daughter, and she does that. But this flaw of hers (her need to follow the rules) never comes to bear. What I would’ve liked to see is for the court to play dirty. They go back on their word and keep Leila away from Billy after he’s done everything he was asked to.

By doing this, you set up an interesting dilemma with Angela, the rule-follower. She’s now presented with a choice. Break the rules so Billy can rightfully be with his daughter or continue to enforce an unfair ruling she morally disagrees with.

That’s not what happens though. Angela is more of a constant force. And constant forces aren’t evolving forces. In my opinion, a character’s status quo should be constantly challenged. The more their morals and beliefs are challenged, the more compelling they get.

Think about that for a second. When are we most pulled in by a character? It’s usually when the core of their being is being challenged.

I actually saw this exact scenario while reading a script a few weeks ago. The entire script was bad. Just really really bad. But there was this one scene – ONE SCENE – and I could only surmise that the writer wrote the thing by accident because it was so unlike anything else in the story. In the scene, a cowardly character who always avoided conflict was walking into a store with his girlfriend and these punks started saying terrible things to her. It was the only time I was drawn in because the scenario cut to the heart of this character’s flaw. Was this guy SUCH a coward that he would allow these bullies to harass his girlfriend? That’s good character exploration there.

Too many writers think these choices should only be explored through their main characters. That’s a mistake. You want to be exploring them through your main three or four characters. Otherwise, those characters are just serving the needs of your hero. They’re not their own people.

Southpaw is a good script. You can tell Sutter’s blood and sweat is in this one and so, even when I didn’t personally agree with something, his passion for the story carried me through. Here’s to hoping the movie is awesome.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: With any sports movie, it’s what happens OFF the field that matters most to the audience, not what happens on it. And what happens off the field can basically be measured by the quality of the three main relationships your hero’s involved in. Make those three relationships compelling and you’re going to have yourself a good script.

The Scriptshadow Newsletter, featuring a review of one of the latest spec sales AND news about The Scriptshadow 250, has been SENT. If you did not receive the newsletter, check your SPAM and your PROMOTIONS folders to make sure it isn’t there.

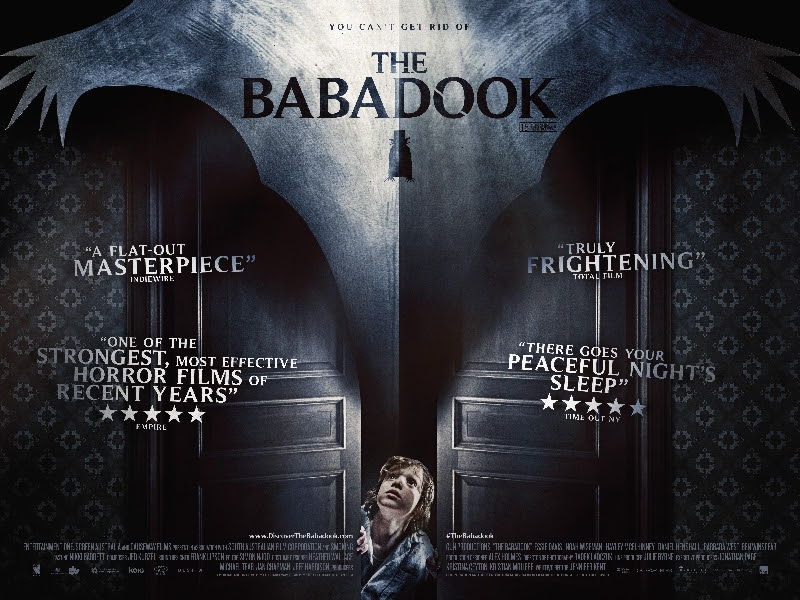

Genre: Horror

Premise: A single mother starts to turn against her developmentally challenged young son when he insists that he’s being visited by a mythical fairy tale creature named “The Babadook.”

About: The Babadook first took the movie-going world by storm during a midnight screening at Sundance, where it instantly broke through and became a buzz-worthy hit. Originally released in Australia, it’s just now coming to the U.S., where it’s in limited release and available on Itunes. Inspired by filmmakers such as David Lynch and Lars Von Trier (whom she worked for once), writer-director Jennifer Kent went into her first directing experience terrified but confident. She felt that if the offbeat and unorthodox Von Trier could direct a film, that she could probably pull one off herself. Of course, she had to make SOME concessions. She originally wanted to shoot the movie in black and white, but was talked out of it by her understandably wary producer.

Writer: Jennifer Kent

Details: 93 minutes

One thing becomes clear as you start watching The Babadook: It’s different. There’s a subdued understated quality to the filmmaking that’s mildly off-putting. I don’t know how to describe it other than to say it’s “lonely.”

Sometimes that works for the movie and sometimes it doesn’t. Because The Babadook really is its own thing. A contained thriller almost, it locks you into this house with a mother and son and keeps you there against your will. For that reason, the film always feels a little claustrophobic. Normally that would be a good thing for a horror film. But is this a horror film?

Some could argue that The Babadook is more of a drama than anything. And Kent seems to support this take when she says she never overtly tried to create a scare in the movie (although I might argue that point with the terrifying Amelia-hiding-under-the-covers “Baaaaa-baaaaaa-doooooook” moment).

But while the movie struck a chord in me in a way that the “Ouijas” of the world could never accomplish, I’m still not sure how I feel about Baba. Maybe expectations have crippled my ability to see the film objectively. I wanted to be scared but instead I was kind of tricked into watching a troubled mother-son story. But isn’t that what all good movies do? Lure you in with the hook then keep you there with the characters? Uggghhhh, my mind says yes but my horror-loving heart says that wasn’t enough!

The Babadook is a simple story. Amelia is a single mother trying her hardest to raise her 6 year old son, Samuel. Samuel’s kind of a troubled kid. He’s prone to bouts of screaming and delusions, making the already difficult task of raising a child THAT much more difficult.

Well, it’s about to get even more difficult. Amelia starts catching Samuel in his room talking to someone, except there’s no one there. When she asks him about it, Samuel says he’s talking to the “Babadook,” the spooky imaginary character from one of his children’s pop-up books.

We eventually learn that the reason there’s no father in this picture is because he died when their car crashed while racing to the hospital during Amelia’s labor. Samuel’s birth literally killed his father, and there’s some deep buried resentment from Amelia because of it.

As Samuel becomes more and more insistent that Mr. Babadook is real, Amelia finally starts to crack, and all those extra hours taking care of her troubled child turn her into a monster hell-bent on killing her son. Thus the question arises. Who’s the real Babadook? The man in the book or Amelia herself?

What’s that old saying? “Be careful what you wish for?” Not long ago after watching Doll Shit – I mean, Annabelle – I complained that horror movies were getting too light. Writers weren’t delving into their characters and those characters’ psyches and finding those evil nooks and crannies that bring true horror to life.

Well, that’s exactly what The Babadook is. It’s a heart-wrenching EXTREMELY intense look at a fractured and complicated mother-son relationship, one where the mother starts to lose it, and becomes convinced that her child must pay the ultimate price. But if this is what I wanted, why don’t I feel satisfied?

I mean this IS what memorable horror movies do. They’re so realistic that you’re afraid they could actually happen. Look at The Exorcist and how realistically that whole situation was portrayed. You didn’t get characters opening bathroom mirrors to look for toothpaste, then closing them, only to see a skeleton face behind them in the reflection. You got those terrifying trips to the hospital with shock therapy, where a mother watched helplessly from outside the room as her daughter was tortured.

That’s the same way The Babadook approached its horror.

And yet… and yet… it felt TOO raw. TOO intense. There’s a scene late in the movie where the mom is so hell-bent on killing her kid that I thought to myself, “This isn’t a horror movie any more. This is just a fucked up mom who wants to kill her child.” It was… disturbing.

With that said, The Babadook is still a film worth seeing because it does something so few horror movies actually do. It dares to be different. As Kent says in one of her interviews, she had no interest in creating any jump scares. This is a movie where the horror gets under your skin and lives inside of you. Maybe that’s why it’s troubling me so much.

But yeah, I mean, look at the way Kent dealt with the story’s monster, which I thought was really clever. We never get a completely clear look at the Babadook, but from what we do see, it’s got this paper-mache design to it, as if it’s being plucked right out of the pop-up Mister Babadook book. How often do we get a unique monster in a horror script? Not often.

Another thing I noticed here was that this was a female writer. You could really tell that. And I don’t say that in a good way or a bad way, but a way in which you could tell this was a different point of view from what we’re used to seeing in horror, where the scares are less foreplay and more “straight to the deed.”

Kent inhabited her lead female character in ways I just don’t see men do. I mean, I see good male writers inhabiting their male characters. But The Babadook was a great reminder that the female characters need just as much of your infatuation as the male ones. You can never BE female if you’re a male. But you can do your best to ask yourself, “What would a woman do in this situation?” “What would a woman think in this situation?” You need this approach if you’re going to add even a fraction of authenticity to your female characters.

Lastly, I just wanted to say that it’s okay to include things in your horror script that people have seen before. For example, The Babadook is built on the age-old conceit of the child who talks to an invisible person. How many times have we seen that before? But it’s okay as long as you’re making a concerted effort to actively avoid cliché in as many other of your choices as possible. The core of this story is an intense honest unique relationship between mother and son that we haven’t seen before in a horror film. And since that’s such a dominant part of the script, we don’t see the “kid sees invisible people” moment as cliché. We only see that sort of thing as cliché when all the rest of your choices are cliche.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the ways to make your script stand out – and horror is a great place to do this – is to tackle taboo or dangerous subject matter. A big reason The Babadook has risen above all these other lame wanna-be-horror movies, is that it presents a truly terrifying situation – a mother who wants to hurt her child. That’s not a comfortable or safe situation to document in a story. Which is why this movie hits the viewer so hard.

What I learned 2: Make sure the creature in your horror film is born out organically from the story. This will ensure that you create something unique. Too many writers only care about creating a cool scary-looking monster. Instead, figure out where your creature is from, and build the monster from there. So if it’s from underground, it might be draped in weeds. If it’s from a giant farm, it might have an Scarecrow-like appearance. In this case, the monster came from a pop-up book, so it had a pop-up paper mache look to it.

No reviews Thursday or Friday (Thanksgiving and Black Friday). So I’m giving you the Thursday article early. There will be a little surprise post tomorrow that you’ll want to check out for sure though. Wish I could tell you more. :)

Say you have a great concept. No, say you have a great concept and a great main character. Say you’re also good with structure and pretty nifty with dialogue as well. You’re rolling into your script like a pitcher on a 15 game win streak. If screenwriting success is a game of odds, you’ve stacked them in your favor.

Why, then, is this scenario not a slam dunk? How come so many writers dribble down the floor, only to get weak knees as they approach the basket? How come those gimme points all of a sudden look like a half-court heave? The answer may surprise you.

I want you to think back to your most memorable movie-going experiences. What is the common denominator? What is it that stays with you from your favorite films? Chances are, it’s emotion. I still remember seeing E.T. as a kid and crying my ass off when he died. At the time, I didn’t know movies were capable of emotional punches like that. Likewise, I’ve never felt so elated as when E.T. came back to life! I was sobbing like the little boy that I was.

The way you can still fail with a great concept and a great character, is if you don’t make your reader FEEL anything. That’s what today’s post is about. If you can make a reader or a moviegoer cry, you’ve given them something they’ll remember for the rest of their lives. It’s the ultimate suspension of disbelief achievement. You’ve done such a great job fooling this person into thinking your story was real, that they actually sobbed about it.

So the question becomes, how do you achieve this? A lot of writers assume that emotional giving is the same as emotional receiving. They think that if you have a character cry, that means the audience will cry too. Think about how many times you’ve watched characters crying in movies. Did you cry too? Usually not.

Getting a reader to cry comes down to one thing: DEATH. Or, more specifically, the “Death-Rebirth” formula. But death doesn’t always have to be literal. As you’ll discover below, any loss can have a death-like effect. However, we’ll start with the literal definition first so you can learn the basics for turning grown men into cry-babies. Then we’ll get to the advanced stuff.

LITERAL DEATH

The most obvious way to get those tear ducts flowing is through a character death. But the journey starts a lot sooner than that, all the way back when we first meet your character. Your first job is to make us like this person. This may seem obvious but in a world where more and more writers are afraid of the word “likability,” it’s important to remember that nobody cries for jerks.

Look no further than E.T. to see this in action. What character in history is more likable than E.T.?? Obviously, the more we like someone, the more we care about them. And once the audience cares about someone, it’s easy to manipulate their emotions. We love E.T. so much by the time he dies, of course we’re sobbing.

To see how the antithesis of this works, look at the recent hit film, Gone Girl. Gillian Flynn has gone on record as saying she hates the word “likable” in relation to characters. And you see that with her characters. Amy is a terrible person and Nick is not a very good one. So guess how you’d feel if either one of these characters died? Would you cry? Would you get emotional like you did in E.T.? No. Because despite the characters being interesting, the fact that you don’t like them prevents you from getting emotional should they perish.

To really ensure that those tears come, though, you need another character who cares deeply for the person who dies. Death alone is not a sad thing. It’s our empathy for the character who’s lost someone that gets us. We saw that with E.T. and Elliot. And we saw it at the end of Titanic, with Jack and Rose.

NON-LITERAL DEATH

Now that you see how that works, let’s look into non-literal deaths. Non-literal deaths include anything that dies. A friendship, a dream, a job, one’s faith. At the end of Casablanca, we have the DEATH of a relationship – Rick and Ilsa, which has led to quite a few tears over time. There’s a trick to this however. Whatever dies has to have meant something to the characters. You can’t kill a trivial job and expect the reader to care. But if you kill a job that we’ve seen a man put his blood, sweat, and tears into for 40 years, like in the film, Mr. Holland’s Opus, then you better believe we’ll get emotional when it’s ripped away.

But I’m not going to talk about death itself because that’s pretty straightforward. The heavyweight emotional moments come from the belief that death is permanent, only for our subject to be reborn again. It’s the non-literal equivalent of E.T. dying before coming back to life. It’s that one-two punch that always gets the reader.

LOVE

Let’s take love as an example. Watching two people fall in love does not make one cry. We need the relationship to suffer before that can happen. We need it to DIE. So just like before, start with a main character we like. Couple that with a romantic interest we like. We should want to see these two end up together. Throughout the movie, throw obstacles at them that prevent them from being together. Maybe they’re involved in a rocky relationship, a la Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Maybe they’re in relationships with other people. Maybe they’re stuck in a friendship, a la When Harry Met Sally. At some point, you KILL the relationship. This is the death part. This happens when Harry dumps Sally after sleeping with her. This destroys us because it feels like death to us, like there’s no coming back from it. How elated are you, then, when the writer brings the relationship back from the dead (Harry tells Sally he loves her and she accepts him)? The REBIRTH moment is what really triggers the emotional response here.

CHARACTER FLAWS

It’s the same thing when you’re dealing with character flaws. Again, start with a character we like. Then give them a flaw. Let’s say it’s that they don’t believe in themselves. Make that flaw a HUGE obstacle in their lives – something that holds them back from their hopes and their dreams. Now create a high-stakes scenario that will directly challenge that flaw. The movie scenario I’m thinking of is Rocky. Rocky never believed he was good enough. The high-stakes scenario that will challenge this flaw is the Heavyweight Boxing Title. How do we get the most out of this moment? If you’ve been paying attention, you know we have to KILL any hope of Rocky overcoming his flaw. We see this when Rocky starts severely doubting himself before the fight. There’s no way he can beat this guy. Rocky doesn’t think he’s good enough. Then, in the fight, Rocky goes toe-to-toe with Apollo, believing in himself more with each round. In the end, he goes the distance with a champion, allowing him to overcome his fear. We thought Rocky’s belief was dead, which is why it’s so emotionally cathartic to see that belief REBORN, to have him conquer that fear. That’s why we tear up.

HOPE

You can apply this death-rebirth model to almost anything. In Toy Story 3, we’re incredibly sad when, at the end of the movie, the toys are designated for a life in the attic. Their hope to ever be toys that are played with again is officially DEAD. So what happens? They’re donated to the sweet little next door neighbor. A REBIRTH. We’re crying because, darn it, we were sure those toys were dead in the water. But now they have a whole new life again.

The more you can convince us of the death part – that there is no chance whatsoever that our character is coming back from it – the more powerful the tears will be when the rebirth occurs. I don’t know about you, but I didn’t see any way that our Toy Story 3 toys were going to be played with again. I thought those chances were dead. So that donation to the girl shocked me, creating a hell of an emotional response.

Of course, this isn’t the only way to make a reader enjoy a story. There are all sorts of emotions to draw upon. There are thrills, for example, like riding dragons through the sky in Avatar. There are scares, like in any good horror movie. There are laughs, of course. There’s shock, like when you find out Bruce Willis is a dead person. All of these emotions should make their way into your story. But there’s nothing quite like making the reader cry. I guarantee you, if you make the reader cry, he will recommend your script to other people.

I’d love to hear what storytelling practices you guys use to elicit emotion from your reader. If you don’t know, go find the movies that made you cry growing up and reverse engineer them until you find the cause. Again, nothing stays with a reader more than a good cry. So it’s in your best interest to figure out how to get them there.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Biopic

Premise (from writer): After the entire Kringle clan is murdered, Santa’s illegitimate son is forced to save his least favorite holiday from a menagerie of supernatural fuckwits.

Why You Should Read (from writer): My name’s Otis J. Kringle and I’m not a screenwriter — I’m fucking Santa Claus. Hang on, that came out wrong, as I am not actually “fucking” Santa — that would be weird and (as you’ll see) necrophilia. More like, I AM Santa Claus. I didn’t used to be, mind you. Truth be told, I’ve always considered Christmas to rank somewhere between getting a colonoscopy from Edward Scissorhands and watching FAILURE TO LAUNCH on a neverending loop. But alas, events unfolded that led me to pick up the jolly red mantle, events like stealing a UPS truck, getting thrown in jail, stepping in reindeer shit, throwing down in fisticuffs with Frigid Bitch and Jack Frost, riding flying lions, massive mall sing-a-longs, things of this nature. I know, right? I was pretty amazed, too. So amazed, I felt the need to share and find an outlet for my story (and movie, because who doesn’t love a new Christmas flick?), namely ScriptShadow. What can I say — I read your site, love the shit out of your site, and as far as I’m concerned, this makes it to a Friday review, everybody who reads your site will be put on the Nice List this year. Even Grendl. I know when you’re sleeping and when you’re awake, — Otis J. Kringle

Writer: Otis Kringle

Details: 97 pages

It’s rare that we get a screenwriter who writes a story based on his own life, which means we should consider today a treat. What makes this even specialer is that our writer appears to be related to Santa Claus. I’m still working on verifying this but I’m 2-4% sure that it’s true. And with the Christmas shopping season starting up next week, what better time to celebrate a Santa-inspired screenplay? Or a Santa-gets-slaughtered-inspired screenplay?

Now I must say that all this murder and mayhem hinted at in the logline has me worried. I’m a Christmas purist. I watch It’s A Wonderful Life every year on Christmas Eve. I download that Band-Aid song and listen to it on repeat. I even purchase egg nog despite the fact that I hate it, just so I can look at it in my fridge and feel festive. Is Otis Kringle about to ruin all that?

In a word, yes.

In another word: “fisting.” As in we’re told on page 1 to go fist ourselves.

Now I’m no doctor, nor do I play one on the internet. But I’m pretty sure that’s physically and biologically impossible. Gonna do a WebMD search on this later to make sure.

Our loser hero, Otis Kringle, the man responsible for telling us to fist ourselves, happens to be the illegitimate son of Santa Clause, who apparently slipped down Otis’s mother’s chimney many years ago, injecting her with many presents.

This will become important later after a dingbat elf in the North Pole named Dunbar Capp sings a song from a cursed book called the Santanomicon. He thinks he’s being jolly. But all he does is release Jolly Klaus, Santa Claus’s long lost half-uncle.

The axe-wielding Jolly slices up Santa along with the rest of his family, then demonizes Rudolph so that Rudolph can slaughter all of Santa’s reindeer.

Lucky for the planet, Dunbar and Blitzen get away and fly to America, where they approach Otis, the bastard child of Santa, to inform him that he’s the only one who can save Christmas. And the planet.

All he has to do is sing a song from the Santanomicon and Jolly will be sent back to the Badlands for another 1500 years. The problem is, all the songs are in another language, which poor Otis can’t read.

Complicating measures are Jack Frost and the Frigid Bitch, an oversexed couple who have likewise been stuck in purgatory for hundreds of years. Being freed allows them to have sex again and boy do they take advantage of it, even singing a song about all the sexual positions they’re going to enjoy together, which number at least a hundred.

Will Otis Kringle, who tells his story in first person, except when we’re around other characters, be able to save the day? Will you be able to save yourself after venturing into a story that introduces the world to the term “cunt brisket?” There’s no way to know for sure unless you read Otis Kringle Hates Christmas. And then fist yourself.

I hear that this Christmas, NBC will be debuting a live Peter Pan musical inspired by wholesome family values and the power of song. If, for whatever reason, this show gets cancelled, I’m sure “Otis Kringle Hates Christmas” can take its place. They’re practically the same movie. I mean, Peter Pan has a song about taking a literal exposition dump, doesn’t it?

Look, I think Otis has problems. He seems a tad angry. And that anger has manifested itself in a script more focused on shock value than story. Shock is a funny thing. It can work in small doses. One need look no further than South Park to see that. But it’s hard to make work if that’s the only thing you’re giving the audience for two hours.

South Park is actually a good gauge for how to make shock work. Underneath all its shocking humor, there’s an undeniable love South Park has for its characters. That love translates over to you loving the characters, and going along with whatever shenanigans, no matter how crass or dirty, the characters find themselves in.

I’m not sure Otis Kringle the writer has that same love for his characters (which is ironic, considering he is one of the characters), which prevents us from ever really connecting to Otis, Dunbar, and Blitzen. We get crass instead of heart. Swears instead of cares. And that creates a wall between reader and character that extends not just to the story, but to the comedy.

And this is why comedy’s the most subjective of all the genres. Everybody needs something different to laugh.

I need to care about the characters to laugh. I believe laughs come from stakes, come from us caring what’s on the line for the characters. And we can’t care about what’s on the line if we don’t connect to the characters in the first place. For example, in Neighbors, I really FELT the importance of our hero’s need to raise a family. So I cared that this frat next door was disrupting their world. And that’s what allowed me to laugh when they kept failing at their goal.

But I concede that not everybody feels this way. For a lot of people, a funny joke is a funny joke, regardless of whether you give a shit about the people involved in the joke. Otis Kringle graduated from the Kevin Smith school of comedy, where the jokes are based on nasty, on disgusting, on shocking and awing your reader. I’m not going to put that comedy down. All I can say is it’s not for me.

With that said, this script has a mission. And that’s to get your attention. And the easiest way to get people’s attention is to be loud and bold, and Otis Kringle is the loudest script I’ve read in years. Throw in some rule-bending (first person writing!), a bizarre mythology, and some snowflake-infused writing talent, and this script will find some fans.

It’s just that for me to become a fan, I have to see that love between writer and character. I need to feel at least some depth in our hero. Sometimes as writers we get so carried away with trying to do that one thing we set out to do when we conceived of the script, that we overlook other basic storytelling components required to make a script work. Otis may have had tunnel-vision in trying to make this that big attention-grabbing script, preventing him from remember that you still have to move people, you still have to make the audience feel something at the end.

The part of me that loves writers who take chances gives this a Millineum Falcon Lego Set present. But the script purist in me gives this a 25 dollar gift certificate to Best Buy. Hey, at least it’s not coal, right??

Script link: Otis Kringle Hates Christmas

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It’s really hard to keep a reader invested for 100 pages on shock alone. I’m sure it can be done, but that means continually one-upping yourself with something even MORE shocking every 10 pages. I wouldn’t want that assignment.

The value of screenwriting contests has been debated for years. I’ve gone on record as saying they’re an important tool in helping gauge where you are in your journey. If you’re not at least making the Quarterfinals (top 50 to top 100) of a screenplay contest, you might want to think about getting some personal feedback on your script to find out what you need to work on.

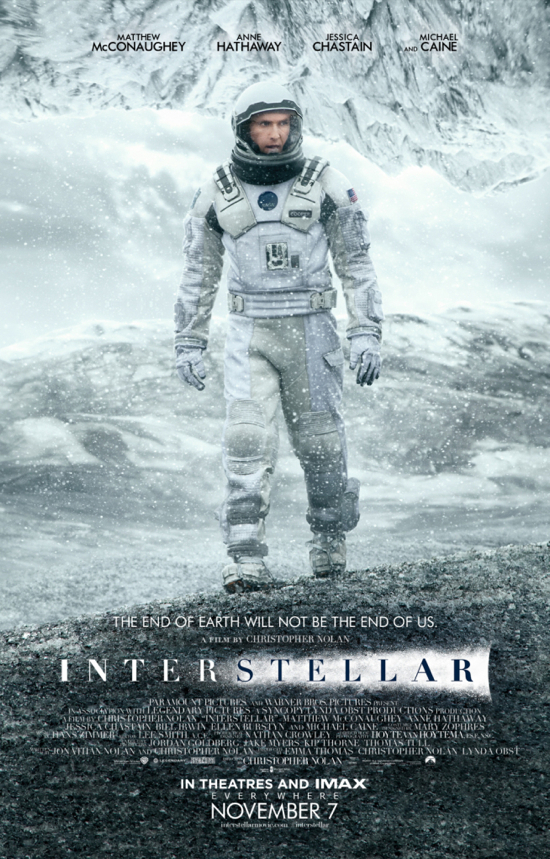

But don’t feel too bad if you’re not lighting up the contest circuit. Believe it or not, there are huge movies out there, movies that have made millions of dollars at the box office, that wouldn’t have even made it out of the FIRST ROUND of a screenwriting contest. Which just so happens to be the subject of today’s post.

That’s right, we’re going to look at ten movies, each of which were either critical or box office successes, that would’ve been laughed out of the big screenwriting contests. Some of these are obvious while others might surprise you. Commenting on these movies will be our hypothetical contest script reader, whose duty it is to explain why the script didn’t make the next round.

Now remember, you have to see these scripts as they’d be seen by the reader. These are naked scripts that have not become successful movies. They don’t have hot directors or actors attached to them. They’re scripts just like you would submit to a contest. With that in mind, let’s check out the list.

Transformers: Dark of The Moon – “Way too long with a story that’s painfully unfocused. Not a single character feels authentic or multi-dimensional. An over-reliance on crass humor, which becomes tired quickly. Way too much emphasis is placed on set-pieces, which would be okay if we understood why they were happening, but often we don’t. Pass.”

Annabelle – “Any horror script that contains a scene where a record player starts playing old timey music on its own is a surefire bet that there will be little if any originality on display. You may as well have a cat jump out of a cabinet while your character’s gone upstairs to ‘check out a noise.’ Horror’s number one enemy is cliché and when a writer shows not even a casual interest in avoiding the C-word, you know you’re in for a long predictable ride. Also, there isn’t a single memorable scare in the script. Death for a horror screenplay. Pass.”

The Monuments Men – “A strange unfocused tale that doesn’t always seem to know what it wants to be. Is it a drama? Is it a comedy? The idea is an interesting one, a story we’ve never heard before about World War 2. But the execution is all over the place. Why, for instance, did the writer choose to split our group of men up for the majority of the story? The group dynamic was the strongest part of the screenplay. To not recognize and take advantage of that shows a writer still learning the craft. It’s too bad. This could’ve been good. Pass.”

Interstellar – “Has the reckless feel of a first or second draft that the writer decided never to perfect. The dialogue is way too expository and on-the-nose, two signs of a beginning screenwriter. For example, lines like, ‘The MRI machines we no longer have could’ve spotted my wife’s cancer before she died.’ Yikes. While there are some interesting ideas about space exploration and time tacked into this overlong second act, everything comes crumbling down in the finale, when the writer tries to wrap up several corners he wrote himself into with trippy pseudo-science explanations. Time-travel is one of the hardest plots to get right, and this writer shows no dedication to figuring it out. Could show some promise with work. As it stands, pass.”

John Wick – “This is one of the most laughable set-ups for an action film I’ve ever come across. The main character, a retired hit man, goes after the Russian mafia because they killed his dog. Outside of a few fresh ideas in the second act, which include a hotel that deals exclusively with hit men, John Wick is bogged down in cliché after cliché. For example, must every action script end in an industrial location? Pass.”

Elysium – “Yet another sci-fi screenplay where the writer fails to explore his world on anything other than a cursory level. There’s no sense of scope at all. People are broken down into over-simplified “haves” and “have-nots.” An orbiting city has a half-ass plan in place for renegade ships breaking through, despite it being a common occurrence. Our main villain, a sword-wielding futuristic samurai type seems to have been ripped from another more fantasy-driven film, exemplifying the lack of foresight put into the script. He’s also bad for the sake of being bad, one of the easiest ways to spot a rushed draft. Feels like we’re five or six drafts away from this achieving its mark. Pass.”

The Counselor – “Script seems to put no value on clarity or narrative focus, often leaving the reader wondering where they are in the story, why things are happening, and what the characters plan to do next. I can’t tell if this was a deliberate choice, with the writer aiming for a high-brow audience who can read minds, or a first-time screenwriter who doesn’t yet understand how to make his plot points clear. Either way, the script completely falls apart when it reaches its apparent goal, the Counselor’s deal going bad, only to make us stick around for another 40 pages, where we’re forced to watch the main character wallow in pity. Writer must learn, amongst other things, that when you’ve reached your destination, the journey is over. Pass.”

Godzilla – “Who is the main character in this script? We’re led to believe it’s army man Ford Brody. But Brody doesn’t make a single decision throughout the entire screenplay. He instead follows a number of other people around and does whatever they tell him to do. Passive characters are the worst characters to lead a story, and Godzilla shows us why. Without a dominant character pushing us forward, we have no one to latch onto, and therefore no one to care about. Script also has a clunky opening, where we watch one parent’s death, only to go through twenty more pages of the other parent before their death. All of this before Brody is formally introduced. One wonders why not just start with Brody and look for ways to imply the backstory instead of show it. The script also spends so much time explaining where Godzilla is, what he’s doing, where he’s probably going next, and how to stop him, that there isn’t any time left for an actual story to develop. You’d think all the explaining would at least go towards setting up big memorable Godzilla set-pieces, but Godzilla only has a couple of featured scenes. A bizarre script that seems intent on avoiding everything that makes a story good. I can’t in good conscience send this one to the next round. Pass.”

Inside Llewyn Davis – “One of the stranger scripts I’ve ever read. The dialogue appears confident, even strong in places, yet there’s no story here to speak of, unless you count a man stumbling through the deliriously morbid world of folk music a story. The main character is such an asshole without a single redeeming quality, that watching him interact with others is akin to listening to metal scrape against concrete on concert-sized speakers. I’ve never read a script where the writer tried so adamently to make us hate their hero and I’m struggling to figure out what the point of that would be. Because we hate him so much, we don’t want him to succeed. Since succeeding is his goal, that leaves the audience with no choice but to root against his success. Can an entire movie hinge on this conceit? I’d say no way, Jose. Pass.”

The Master – “There’s a movie somewhere in this script, but the writer seems unwilling to find it. One of the script’s biggest problems is in its scene writing, as very few scenes have focus or structure. In fact, we’re often unsure where the scenes are headed or when they’re going to end. There’s a scene where the main character, Freddie, for example, gets fired from a department store, that could’ve ended on four different occasions. I like when writers give me something unexpected, but these scenes feel more like the writer himself didn’t know where he was going. The script picks up when religious leader Lancaster Dodd begins to mentor Freddie, only to delve back into an unfocused story that seems uninterested in having a point. Writer needs to get to the religious cult sooner, and focus more on the growth of the cult under the Lancaster and Freddie dynamic, as that’s when the script shines brightest. However, I have a hard time believing this writer is capable of writing a focused story. Pass.”

And there we have it! So what does this MEAN exactly? Does it mean screenplay contests are flawed? I don’t think so. I think it means Hollywood has a huge weakness in two areas. – the big budget flick and the writer-director vanity project. Both can end up bad for, ironically, completely opposing reasons.

The big-budget tentpole/franchise films have too many cooks in the kitchen. This results in either a highly compromised uber-safe film (Olympus Has Fallen) or the overly bloated film where every single idea gets added (The Amazing Spider Man 2).

The writer-director projects, when they go bad, go bad for the opposite reason. There’s only one cook in the kitchen. They don’t have to win over anybody with their script, so if the script is bad, there’s no checks and balances system to prevent them from making it.

If you’re a writer who wants to win a contest, you should be doing generally the same thing as a writer who’s trying to sell a script. Write something with some marketable element and then write the tightest and most entertaining story you can. If you do a good job at that, you’ll find yourself making it past the first round of contests easily, and possibly getting much further.