Search Results for: F word

This juicy high-concept show starring Mahershala Ali will be Hulu’s next big buzzy “whodunnit.”

Genre: Thriller/Mystery

Premise: A once successful author does the unthinkable and steals a former student’s book idea after he learns of the student’s death. But after the book becomes a #1 bestseller, someone on social media begins taunting him, telling him he knows what he did.

About: Today’s author, Jean Hanff Korelitz, originally wanted to be a literary novelist, writing “important” and “thoughtful” character-driven stories. Until she realized the reality of her voice as a writer: SHE LOVED PLOT. Thus was born, “The Plot,” a book she said was the perfect writing experience. It shot out of her, uninterrupted, in six months during the pandemic. The sexy concept was quickly picked up by Hulu to turn into a series, which will star Academy Award winner, Mahershala Ali.

Writer: Jean Hanff Korelitz

Details:350 pages

Since we’re talking about the power of concept today – coming up with that big juicy movie idea – I wanted to remind you guys that I do a “Power Pack” logline consultation for 75 bucks. You send me 5 loglines. I give you analysis, rate them on a 1-10 scale (don’t write a script that gets less than a 7!) I rewrite each logline, and I rank them from best to worst. This is great for writers trying to figure out what script to write next.

I also do a la cart logline analysis. It’s $25. Use my expertise of having been pitched over 20,000 loglines to know if your idea is truly worth writing. Just e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com

Okay, on to today’s review. We’re going to talk about a lesser-known sub-genre in the storytelling universe called the “walls are closing in” narrative. Now, the “walls are closing in” narrative has a couple of advantages and one distinct disadvantage.

What it offers is this impending feeling of doom as the truth begins to close in on our hero. You’ll see this in movies where the main character has killed someone and the cops come sniffing around. As the story goes on, we can almost physically feel all avenues of escape shrinking. The walls come from around, above, and below, squeeeeeeezing until they’ve entrapped our protagonist.

It’s a fun narrative because we’re hoping that the protagonist somehow figures out a way to escape.

But there’s a second advantage to these movies that not a lot of writers are aware of. Which is that the main characters are a lot more interesting than your average main character. They’ve obviously done something bad in order to be placed in such a situation. That life-changing mistake creates this internal battle that the character must fight off throughout the story. You know you’ve written good characters when the story stops and we still want to watch those characters. The main reason we’ll want to do this is because they’re going through some major internal struggle, which is exactly what the “walls are closing in” narrative provides.

But that leads us to the downside of these narratives, which is that the characters leading them are passive. Often times, with “walls are closing in” narratives, the main character is waiting around. They’re hoping they don’t get caught. At best, the characters are running around, defensively protecting themselves from being discovered.

As you may know, the best stories are almost always stories where the main character is active. He’s going after something. Let’s see how The Plot addresses this.

Jacob Finch Bonner was once a prodigy. His book, “The Invention of Wonder” was critically acclaimed and became a New York Times best-seller. But it’s been a decade and, two books later, Bonner is seen as an also-ran, one of many famed authors who fell off a cliff.

It’s gotten so bad that Jacob was forced to accept a teaching position at a writer’s summit in a small college called Ripley. Dozens of writers paid to come and learn writing from real authors for a month and then went off and tried to apply their newfound knowledge to their own novels.

While there, Jacob meets the most pompous writer ever, a handsome kid named Evan Parker, who has the gall to tell Jacob that he doesn’t need any writing help. He already knows he’s a great writer. He just needs contacts for when he finishes his book, a book, he claims, that will be one of the best books ever.

Jacob internally laughs this off but then, in a private meeting after class, he asks Evan to tell him about the book and Evan does. Jacob is shocked to learn, as Evan goes through the plot, that it, indeed, will be one of the best books ever written. There’s no hesitation in that analysis. The story, which includes a whopper of a twist, is *that* good.

The summit ends, everyone goes their separate ways, and three years later, out of curiosity, Jacob looks up Evan Parker. He’s confused why he hasn’t seen Evan’s book get published. As it turns out, Evan is dead. He died of an overdose.

It doesn’t take Jacob long to decide what he’s going to do. He’s going to write Evan’s book. And he does. Cut to three years later and Jacob is back on top of the publishing world. But “Crib’s” success dwarfs anything he experienced with The Invention of Wonder. Even Oprah wants to interview him.

Evan even gets a wife out of it! A producer on a Seattle radio show named Anna first falls in love with the book, then with the man who wrote it. And Evan is living every writer’s dream. Until one day, on his website, someone leaves a comment: “You are a thief.” From that point on, Jacob’s dream becomes a nightmare.

Not because anyone is trying to kill him. Because now every minute of Jacob’s life is a minute lived in fear. Will today be the day he’s exposed? At first, the comments come every couple of months. But the mystery person gets on Twitter and starts telling anyone who will listen, that Jacob stole “Crib.”

It gets to the point where the publisher finds out and now they want to know what’s up. Jacob, of course, tells them it’s a lie. But it’s getting bad enough that he can’t just wait around anymore. So Jacob heads back to Ripley College, the area where Evan Parker lived, to see if he can learn anything about who Evan was close with, in the hopes of finding the troll. What he learns is that he already knows the answers to his questions. Because the answers are written in his book.

“The Plot” is a great example of how to come up with a low-key high-concept idea. When you think of high concept, you usually think of something involving dinosaurs, time travel, switching faces. But there’s this whole other range of options below the high-profile versions of high concept that can give you a more affordable great idea.

Some low-key high concept movies that come to mind are Double Jeopardy, Her, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Groundhog Day, Memento, Limitless, and Yesterday.

A writer who steals a concept from a dead writer only to learn, after his outsized success, that someone knows his secret, is indeed, a juicy setup for a movie (or, these days, a show) that isn’t going to break the bank. Which is why everyone on this site should familiarize themselves with low-key high-concept. Still, to this day, it’s one of the best ways to skip the Hollywood line.

And like I said at the outset, the idea lends itself to a fun “walls closing in” narrative, which I think the writer executes well. That first message Jacob gets (“You are a thief”) reminded me of that famous 90s horror thriller line: “I know what you did last summer.” I was scared for Jacob. Because it’s a unique threat in that there’s nothing you can do about it. At least not yet. All you can do is wait and hope that it somehow goes away, even though you know it won’t.

But what impressed me about The Plot is the thing that I keep telling every writer to do. Find a familiar concept/format/genre/plot and put a spin on it. The Plot is a “whodunnit”….. EXCEPT THERE’S NO MURDER. That’s what makes it unique. Once Jacob decides to do something about this troll, he becomes an investigator. He travels to Evan’s old town to learn about him and, hopefully, figure out who’s sending him these messages.

By the way, that’s how the book handles the “walls are closing in” weakness. It gives its main character a goal of finding out who’s posting these comments. That makes him active. So he’s not standing around the whole show.

Ironically, it isn’t the plot that puts this book on top. It’s the thing that the author claims to be least interested in: character. Because what this story is really about is the struggle of being a fraud. It’s a lot like “Yesterday” in that sense. You have everything you’ve ever wanted. But do you really have it if you ripped off the idea from someone else?

And that’s where The Plot becomes its most interesting, at least for fellow writers. Because it gets into a nuanced discussion about what constitutes “stealing.” Jacob wrote every word of this book. He didn’t use a single line of Evan’s work. So did he really steal? Evan had this plot. And he had this amazing twist. But Jacob wrote it. And that’s what he’s holding onto to keep his sanity. He keeps reminding himself that he wrote everything. But is he just doing that to feel better about what he’s done?

The big weakness in the book is the excerpts from the novel, “Crib,” that Jacob wrote. It’s supposed to be this amazing novel (it basically follows a toxic mother-daughter relationship) but nothing in Crib is as good as anything in the novel we’re reading, “The Plot.”

With that said, “Crib” starts to get juicier towards the end when we realize that the characters in “Crib” were Evan’s mother and sister. Now, if someone tells the world what happened to Evan’s mother and sister, it will clearly expose Jacob as having stolen the story from someone else.

I’m back and forth on whether this should be a series or a movie. Ideally, it would be something between the two. That’s always been the problem with novel adaptations. They’re always too big to be a movie and too small to be a TV show. So if you’re going to make a TV show, you need really good writers who can expand on the detail within the novel to keep the story moving during episodes 3, 4, and 5, where a lot of these bad 1-season TV shows die out.

But I think it’s going to work. Ali is great casting because he looks trustworthy. And I could see him depending on that to gain trust from family, friends, fans. Whereas, internally, he’s the biggest fraud in the world, something you’re typically not expecting with that actor. Remember everyone, one of the best ways to create great character is to make what’s happening inside of them and outside of them as opposite as possible. Success, fame, recognition outside. Shame, fear, feel like a fraud inside. That’s what’s going to make this show work.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is a major spoiler WIL. You’ve been warned. Whoever your “killer” is needs to be treated like every other character throughout the novel/script. Anna, Jacob’s wife, is treated so oddly throughout this story. She’s never around. Whenever she is around, she’s a wallflower. Whenever she talks, she’s very non-specific, vague. Meanwhile, every other character gets a super-detailed life. Anna is treated so differently that we know something is up with her. And, of course, she turns out to be Evan’s sister. She’s the one who’s been threatening him. Whenever you have a twist ending, you want to put yourself in the reader’s shoes and ask, “Who would they think the killer is?” Then make sure, whoever they’d think it is, NOT TO MAKE THAT CHARACTER THE KILLER. Not enough writers realistically evaluate readers when they do this.

What I learned 2: What you want to do instead is let Anna (or whoever your version of Anna is) be the disco ball. She’s the pretty shiny thing we’re all looking at over here so you can shock us at the end with that guy/gal we weren’t expecting at all.

Is “Suits” a perfectly constructed pilot?

Recently, I read an article that the two biggest streaming shows in America were Gray’s Anatomy and NCIS.

I’ve never personally met anyone who’s seen an episode of NCIS so, naturally, this was confusing to me.

I was also confused when, amidst a bottomless pit of shows on Netflix, many of which have had giant advertising campaigns, that the show that had become the most popular was one that had ended four years ago, “Suits.”

We have been led to believe that the TV landscape is dominated by prestige television shows such as Breaking Bad, Succession, Game of Thrones, and White Lotus. But the reality is, shows like Gray’s Anatomy, NCIS, and, yes, Suits, are the shows that truly get the ratings. Just not the love.

I decided to find out for myself if Suits was worthy of all the hype or if it was merely a curiosity brought about by the world’s obsession with Megan Markle (who plays a major character on the show). What follows are my thoughts.

Suits is set in New York City and follows a law firm led by Jessica Pearson, who’s trying to figure out if she should hand the firm down to her best lawyer, Harvey Specter. The problem is Harvey (a young George Clooney doppelgänger) is an arrogant blowhard who only cares about himself.

Harvey is on the lookout for a new lawyer, which is where Mike Ross comes in. Mike is a super-genius who’s had his life derailed by a couple of bad decisions and is in such a bad place that he actually agrees to deliver a suitcase full of drugs for money (that he plans to use for his sick grandmother, of course).

Mike goes to a hotel to make the drop but susses out that he’s being set up and makes a run for it… right into Harvey’s lawyer interviews. Mike stumbles his way into Harvey’s office where he accidentally opens the suitcase and all the drugs fall out.

Intrigued, Harvey asks Mike why he has a suitcase full of drugs and Mike tells him the truth. Further discussions lead Harvey to learn that Mike is beyond a genius and could run circles around all the Harvard applicants in the lobby. The kid is so raw, Harvey almost turns him away. But, in the end, he decides to take a chance on him. This leads to Mike’s first big case, a sexual harassment lawsuit.

Let’s cut to the chase.

Good writing is good writing is good writing.

It’s what I always tell people. Good writing prevails above all. It is almost impossible to find something that’s well written and completely ignored. Because good writing is rare. So when it arrives, it tends to birth a good product.

When it comes to TV, there are three writing ingredients that must thrive. The characters, the dialogue, and conflict. If you are good at these three things, you will be good at writing for television.

Cause TV isn’t so much about plot. Especially episodic shows like this one (case of the week). Plot is more for movies. The reason for that is, a movie needs a conclusion. And that’s where plot leads us. It gives us a goal and then, at the end of the story, we either succeed or fail at achieving that goal.

TV doesn’t need to end. It keeps going. So while there is plot in each individual episode (try to win the case), the plots are devoid of the kind of stakes that really matter. Cause who cares if Harvey and Mike win this week’s sexual harassment case? There’s going to be another one, just like it, next week.

For that reason, audiences come to TV shows more to hang out with the characters. Which is why all your TV writing should start with creating great characters.

Mike is a perfect character. Why? Two reasons. He’s an underdog and he’s super smart. These are two things that audiences DIE FOR. They love underdogs more than anything. This guy who didn’t even graduate law school being thrown into one of the biggest firms in New York — we love watching sh*t like that.

On top of that, audiences love characters who are smarter than everyone. There’s an early scene where Mike sniffs out that two men in the hallway (pretending to look like a bellhop and a guest) may be cops and he’s been set up with this drug delivery. So he asks the bellhop, “Hey, I was thinking about taking a dip later. How’s the pool here?” “It’s one of the best in the city, sir. You’ll love it.” Then we do a quick flashback of Mike earlier walking past the pool and a sign that says, “Pool closed for the summer.”

So we immediately know that Mike is smart. He uses his power of observation to stay ahead of everyone.

Then you have Harvey. I still don’t know exactly what the line is between hateable a$$hole and lovable a$$hole, but I know that audiences love lovable a$$holes. As long as the a$$hole is on our side.

One trick I’ve learned is to put our lovable a$$hole in the room with people who are worse than him. There’s an early scene where a client tries to railroad Harvey for not getting him everything he wants in their deal. But Harvey stays calm and outsmarts the guy, winning the conversation. In other words, if your hero is a bully and you want to make him likable, just add a bigger bully.

When it comes to dialogue, one thing I’ve noticed that these episodic TV shows live by is metaphors. They’re always using metaphors in the dialogue, which helps make the dialogue clever.

So, in the above scene where the client yells at Harvey, Harvey takes out a receipt of funds transferred and tells the guy that any threat to terminate their contract doesn’t matter because the firm has already received his money. The guy huffs out and it’s revealed that the piece of paper was a pointless memo. Harvey was lying.

Harvey’s boss then asks him, “How did you know he wouldn’t look closer and realize you were lying?”

Think for a second how you would write Harvey’s response. Because most beginner writers would write something like, “He’s a bully. And bullies never look closely at the details.”

It’s a lame lifeless line.

Here’s the line that Harvey actually uses in the pilot: “Cause a charging bull always looks at the cape, never the man with the sword.”

Now, is this the most brilliant line in the world? No. But it’s better than, “He’s a bully. And bullies never look closely at the details.” The metaphor automatically upgrades the line into something with more pop.

With TV, you really have to be on your dialogue game. If you are not a dialogue person, definitely stay away from this medium. It’s easier to get away with a lack of dialogue prowess in features because features are more plot driven, depend on exposition more (which is more technical), and are more about showing as opposed to telling. So you don’t have to write as much dialogue if you don’t want to.

Finally, we have conflict. Conflict is very simple to create. You put two people in a room who don’t see eye-to-eye, either about what’s happening in the moment, or in how they view the world in general. Or you give characters little goals and then throw obstacles in front of those goals.

The reason obstacles are great is not just to create conflict – which they do – but because they give your characters opportunities to shine, which is both entertaining and make us like the character more.

So that moment where Mike walks up in the hotel hallway and sees the bellhop and the fake guest — that’s an obstacle. Notice how Mike using the “is the pool open” bait shows him dealing with the obstacle in a clever way, which makes us like him more. The cops-in-disguise then chase him, which is where the conflict comes from.

Also, in the very next scene, when Mike interviews with Harvey, there’s conflict in that scene as well. Harvey clearly likes Mike. But he can’t hire someone who hasn’t even graduated law school. So there’s this tug-of-war where he challenges Mike with a series of problems that Mike passes one by one. Mike eventually wins him over and the conflict is resolved.

So if you’re good at these three things – character, dialogue, conflict – you can be a TV writer. And Suits is a great show to study for how to do it right.

[ ] What the hell did I just stream?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I don’t know if there’s a better setup than taking someone who’s perceived as “not intelligent” (or who has street smarts, or who does things differently than you’re supposed to) and putting them in a scenario where they’re competing against the “smartest people in that industry.” It’s built perfectly for us to feel a sense of satisfaction every week when our supposedly “dumb” hero outsmarts the “smart” guys once again.

Do we have a new Top 25 script on our hands!!?

Genre: Thriller

Premise: After a devastating wildfire wipes out a small California town, a teenage girl is missing and presumed dead. A year later, an obsessive mother and cynical arson investigator begin to suspect that she’s still alive…and in the clutches of a predator.

About: Dan Bulla is one of the newer writers on Saturday Night Live, joining the longstanding sketch show in 2019. He also wrote an episode of the Pete Davidson show, Bupkis. This script finished on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Dan Bulla

Details: 111 pages

Mark Ruffalo for Nick?

Mark Ruffalo for Nick?

It is the most wonderful time of the year.

No, I’m not talking about the return of football. I’m talking about the U.S. Freaking Open! I’m currently bouncing around between watching 128 first round matches, having the time of my life.

It was during this trip to nirvana that I thought to myself, “You know what would be nice? Reading a script about a forest fire!” Hey, I can’t defend how my mind works. It does what it wants to do and I try and keep up.

Little did I know I’d be stumbling into a bona fide banger of a screenplay!

40-something Jessie lives in Avalon, California – one of those small Northern California towns in the middle of endless forests. And on this morning, it’s a bad day in Avalon. A massive forest fire creeps up out of nowhere, causing a mad dash to get out of town.

Jessie and her husband, Ken, are assured by the local police that the high school has been evacuated, meaning that their daughter, Wendy, is okay. Still, they barely escape and get to the rendezvous point, where they learn the devastating news that Wendy secretly ditched school that day.

Cut to Wendy and a couple of her friends goofing off in the forest when the fire approaches. They make a run for it but get split up, and Wendy finds herself on a road that is blocked in both directions. Just before she’s about to die, a red pickup truck arrives and a man named Randy saves her.

Cut to a year later and we meet Nick, a private fire investigator. Nick is in Avalon to meet Jessie, who says she has evidence that the fire was not, indeed, caused by a downed electrical generator, but rather by arson. Nick has a lot invested in Jessie’s claim because he’ll receive a giant windfall of cash if he can get the electric company off the hook.

Unfortunately, Jessie seems flat-out crazy these days. She lives in an RV in this shell of a town, collecting burned-up debris in the hopes of proving there’s more to this fire than meets the eye. Nick knows that her theory is weak from the get-go and considers turning around and leaving immediately. But Jessie’s emotional plea to help her figure out how her daughter died gets Nick to stay.

The next day, Jessie shows Nick a mysterious gray line she found in the burnt-up forest. Now Nick is interested. This line implies that the fire was started by arson. Which means somebody planned this. He further figures out that Wendy may not have died after all. Could these two things – the arson and Wendy’s disappearance – be related? And, if so, who, in town, has her? Nick and Jessie will have to team up to find out!

Let me say that this is the first script I’ve read in months where I thought I was a lot earlier in the script than I was. I thought I was on page 60 and it turned out I was on page 85! Usually, it’s the opposite. I think I’m on page 60 and I’m on page 20.

That’s screenwriting code for: this script was awesome.

I liked the script even before I opened it. It’s a fresh concept. We don’t usually see serial killers and wildfires in the same story space. It’s a unique combination. More importantly, it rewrites the investigation narrative. Usually, when we read about a killer or an abductor, it takes place in a city, which means that every investigatory beat in the story is one we’ve already seen before.

Here, the investigatory beats are all unique because we’re in a bunt out town in the middle of nowhere. We’re not going to apartments in Brooklyn asking cousins when the last time they saw Jenny was. We’re in a forest examining dead animal carcasses. I can’t emphasize enough how important this is. Readers read the same stuff OVER AND OVER again. So if your plot provides a world with a bunch of fresh scenarios for your characters to engage in, you’re up on every other screenwriter in the business.

As always, these scripts depend on authenticity. I always say to writers – if you’re writing about a specialized subject matter, you better know a lot more about that subject matter than I do. If I think we know that subject matter evenly, I’m done with your script. Cause I know you didn’t do any research, which means you’re not trying. I don’t have time for writers who don’t try.

I LOOOVED the opening forest fire scene here. It was SOOOOO intense. And the level of specificity to it was impressive (the way this fire spreads sounds eerily similar to what happened in Hawaii recently – and this script was written a year before that happened). There’s this moment where they’re desperately trying to get out of this logjam of cars and they finally break through and they’re racing against the smoke and they look over and there are these deers who are right next to them, also trying to escape. It felt so specific, like the writer was fully tuned into the sequence.

The writer also knows how to navigate the nuts and bolts aspects of storytelling. For example, there’s this early scene with Nick where the writer wants to establish that Nick knows what he’s talking about. You do this in screenwriting because it gets the reader on the character’s side. Readers LOVE when the character knows something that the average person doesn’t.

There’s this moment where Jessie is trying to convince Nick that a bottle rocket was the cause of the fire. Nick takes a look at the bottle rocket and the affected area and says this: “There’s deep char on the right side of the trees. Minimal char on the left. Burns rising, right to left, steeper than the slope. Branches all bent in the same direction. Foliage freeze. That means the wind was blowing right to left at the time of the fire. No odor. No sign of accelerant. It’s burned on top, untouched on the bottom. That tells me that a fully formed, advancing fire swept over this area, right to left, at about six miles an hour. The bottle rocket didn’t start the fire. It’s just some litter you found in the woods.” If there was any doubt that this guy is a fire expert, this assessment puts it to rest.

And then there’s this little moment early on that told me I was dealing with a guy who KNOWS SCREENWRITING. Jessie gets Nick to stay one more day by telling him that, tomorrow, she’ll show him a piece of evidence that will prove the fire was created by arson. The day comes, Nick shows up at her place, and says, “Where’s the evidence?” And she says, “Change of plans. First you’re going to tell me what happened to my daughter.”

The words “change of plans” should be a part of every screenwriter’s vocabulary. Why? Because YOU NEVER WANT THE READER TO GET COMFORTABLE. You don’t want them having a sense of where the story is going all the time. “Change of plans” throws the reader off. Cause now we’re going in a direction that wasn’t a part of the original plan. It’s exciting.

Not that you have to use those exact words (“change of plan”) every time. It’s more about you, the writer, occasionally changing things up so you don’t stay on that same predictable path the whole story.

Oh, one more thing. In a lot of the scripts I read, the bad guys never get the deaths they deserve. They get these quick weak deaths where they don’t suffer at all. This bad guy gets a terrible death and it’s awesome.

All this adds up to a really good screenplay. One of the best – maybe even the best – scripts on last year’s Black List. Definitely check it out!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive (Top 25!)

[ ] genius

What I learned: There comes a time in a lot of scripts where a character will remember something about their loved one and share that experience with another character. These memories are one of the best ways to separate yourself from the average writer. Cause most writers have these boring on-the-nose memories they have their character recall.

“Oh, I remember when Wendy was 7 and she fell in the pool and she didn’t know how to swim and so I jumped in after her and I pulled her out and she wasn’t breathing and I’ll never forget giving her mouth to mouth. I thought for sure she was going to die. But, then, at the last second, she let out a breath. And it was at that moment that I knew my daughter was a fighter.”

Note how unimaginative that is. Note how 99 out of 100 writers would’ve been able to write the same thing. Real memories are unique. They have weird details. They don’t go according to plan. And they rarely line up with the five cliched memories that most writers use in these instances. Note how different, even a little bit odd, the chosen memory Dan Bulla uses for Jessie when she shares a story about Wendy…

“One time, I sat in the living room all night, waiting for her to come home. Just absolutely fuming. She finally snuck in just before sunrise. Didn’t see me sitting there in the dark. She shut the door. Locked it without making a sound. Then she went upstairs, straddling the steps so the stairs wouldn’t creak. And I didn’t say anything. I just watched her. And I remember feeling lucky. Lucky to witness that. Because I was seeing her. The real her.”

Is this the first time Scriptshadow gets sexy in a script review??

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from Black List) A successful author/wife/mother plans a trip to a bucolic island to crack her next book and finds herself in a surprising situation.

About: Today we get the rare CELEBRITY script, as Power Rangers’ very own Amy Jo Johnson wrote today’s screenplay, which made last year’s Black List. More actors should be writing their own material and creating their own way like Amy Jo Johnson. The woman is a straight-up inspiration. Now someone please tell me what “bucolic” means.

Writer: Amy Jo Johnson

Details: 114 pages

Today is a first on Scriptshadow.

I am about to do something that I’ve never before been faced with on the site.

I am going to read a script from one of my early crushes.

We’re talking Mighty Morphin Power Rangers. Felicity. And the utterly underrated, “Hard Ground.”

Amy Jo Johnson everyone. If you don’t know who that is you need to be arrested for dumbness.

Look, it’s not going to be easy reviewing today’s script. How can I ever judge AJJ objectively? What am I going to do if the script is an Amy Jo Disaster? Even if AJ has never heard of the site, I’ve learned that most of the writers of these scripts are made aware of the review at some point or another. Does that mean any potential future between Amy and I is 69’d? Wait, not “69’d.” That’s the wrong term. What’s the right word? 86’d! That’s what I meant to say. “86’d.” Honest slip of the keyboard. Sorry about that, guys.

Let’s get to the script!

Jennifer is a 45-year-old novelist with a family and a husband, Steven, who’s her biggest fan. Well, he *was* her biggest fan. He’s the agent who signed her and began her successful run on the best-seller list. But Jennifer hasn’t written a book in 5 years. She’s got an ugly case of writer’s block.

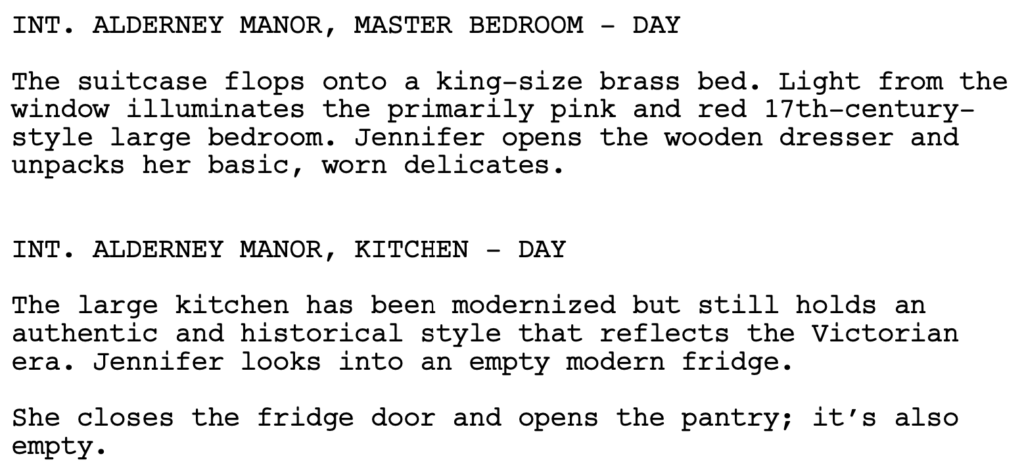

So Steven decides to rent Jennifer a house in the middle of nowhere (Alderney Channel Island) for three weeks so she can finally finish her latest book, “What We Became.” Jennifer doesn’t want to do it but the reality is, they’re running out of money. If they don’t start selling books again, they’re going to be looking for studio apartments on the south side of the 10 freeway.

Once on the island, Jennifer meets a young beautiful woman named Kathleen. Kathleen informs her that the house Jennifer is staying at was used by the Nazis for secret meetings back in World War 2. Kathleen offers to bring groceries over, periodically. But not any normal groceries. SEX GROCERIES (‘sex groceries’ is a term I just made up. It means getting people groceries when what you *really* want to do is have sex with them).

Jennifer is both elated and mortified by her desire for Kathleen. But what is she gonna do when the hot little number keeps swimming naked in her pool? I mean, who can resist that? Not Jennifer.

Not long after they start sleeping together, Jennifer heads into town and meets Kathleen’s mother by chance, who tells her Kathleen is dead and has been for five years. Wrestling with her newfound potential necrophiliac status, Jennifer confronts Kathleen, who admits that she’s not Kathleen. She’s actually a fan.

Jennifer is so turned on by this chick that she keeps sleeping with her anyway, despite the creepy fan stalker issue. It helps that she’s flying through the pages of her novel. She’s never been this inspired in her life. She’s so inspired that she straight-up ignores her husband’s calls, to the point where Steven gets worried and flies to the manor, where he learns that his wife has been sleeping with the help.

After a big blow-up between Jennifer and Steven, Jennifer has to figure out, once and for all, who her lover is. Is she a liar, a ghost, a Nazi, a stalker? One thing’s for sure, whoever Kathleen is, she’s unstable. And that lack of stability is going to lead to a giant confrontation.

I have good news, everyone.

I liked it!

You all know this about me. Put a character on an island and I’m in.

Make them a writer and I’m even more in. Of course I’m going to be pulled in by a story set in the subject matter of my chosen profession.

The only thing holding this script back is the fact that, with the wrong director, it becomes a cheesy Netflix romantic thriller. But with a good director, it could be awesome.

Cause Johnson writes in a sophisticated enough way that the story is elevated above your run-of-the-mill romantic thriller. She’s very detailed when she writes. She’s good at describing the setting – adding just enough detail to convince us that we’re really there.

In scripts like this, it’s the sum of all the mini-parts that elevate the script above average-ness. For example, this could’ve taken place anywhere. In some generic woods setting, for example. Placing it on the Alderney Channel Island, an island I’ve never heard of, off the coast of Britain, made it feel real. Specifics and detail help your story every time. Never forget that.

I say that as someone who just read two scripts from writers who used little-to-no-detail. Who always went with the basic general option. It’s the difference between having your characters get the pear-gorgonzola gelato at Gelateria Fatamorgana and… your character go to the “ice cream shop” to get “yummy ice cream.” Specificity makes a difference.

Another thing that impressed me here was the sex stuff. We don’t usually talk about sex on the site. Sex scenes are tricky, to shoot as well as to write. Because if you’re too soft, they’re boring. If they’re too hard, they become exploitative and overwhelm the moment, pulling the reader out of the story.

I thought Johnson wrote these perfectly. The scenes are sexy, slightly original, occasionally push the boundaries, and most importantly, remain authentic.

I think the reason sex scenes can be challenging is because, in order to make them authentic, we do have to bare our soul a bit. We have to give those uncomfortable details of our own sexual experiences because those are details that make the moment feel real. If you try and write, “He gets on top of her. They kiss. She moans.” That’s not going to cut it. It’s too generic to make an impact, especially in a script like this where the sex is a key component to the plot.

If I have any complaints about the script, I’d say Johnson relied too much on twists and turns. I loved the first twist of Kathleen being dead. I thought, “Ooh, are we going into ghost territory here?” Then there’s another twist where we learn she was just saying she was the dead girl to hide her own identity and that she’s actually a fan. Then there’s another twist still that she’s never read one of Jennifer’s books. And there’s even another twist after that.

Twists are fun. But most scripts can’t handle more than two big twists. Cause if every ten pages is a twist, then we stop believing in what’s happening and we don’t trust the writer anymore. Just to be clear, smaller twists are fine. But big twists? 1 or 2 is all you need.

Let’s be honest. The “romantic thriller” isn’t the coolest genre on the block. A lot of industry people roll their eyes at it. But if you’re passionate about a genre, even if it isn’t cool, you should write in that genre. Cause that’s the genre you’re going to be the most passionate writing. That passion is likely to result in a good script, like this one.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t introduce juicy red herrings that you’re not going to pay off. That’s like promising steak for dinner and cooking SPAM. Red herrings are a great way to get the reader off your scent. I encourage using them in any mystery. But don’t introduce a big fat juicy red herring – like Nazis – and not pay it off. Cause it’s just going to upset the reader. I was hoping that the Nazis came back into this script somehow after they were mentioned in the first act. So I was bummed when that setup was abandoned.

Is today’s script the best horror entry of the entire 2022 Black List??

Genre: Horror

Premise: To save her friend, a maid in a decaying manor must unravel the secrets of its inhabitants while confronting spirits, her own terrifying abilities, and the very real horrors of Depression-era America lurking outside the door.

About: Another writer brand new to the scene here. But that doesn’t mean he hasn’t been putting the work in. Evan Enderle has been writing screenplays for at least six years as he was the recipient of the 2017 Rough Draft Residency with The Drama League in New York. Put in those reps, everybody! Assuming he wrote between 1-2 scripts a year since then, he could have as many as ten screenplays under his belt. In my experience, somewhere between 6 and 10 scripts is when a writer finds their screenwriting legs. We’re going to talk about how many scripts screenwriters should be writing in the next newsletter as I’ve come across lots of writers who are approaching it the wrong way. If you want in on my newsletter, send me an e-mail at carsonreeves1@gmail.com.

Writer: Evan Enderle

Details: 112 pages

A hurricane?

In LA?

Is that even possible?

This past week I was hanging out with extended family on vacay. For perspective, my family was seeded, and then sprouted, from the endless fields of Indiana. They are proudly mid-western and, because of this, I wanted to know what kind of content they were into. What movies does the “Average Joe and Joan” in middle America up and leave their houses to see? What shows did they drape themselves in potato chip crumbs to binge?

I got only two universal answers.

They all loved Barbie.

And they all loved White Lotus.

Well, at least they half have good taste.

As much as I’d like to take you down another backroad of Barbie Land and trade definitions of the patriarchy, we’ve got a new script to review! I know Poe’s been hyping this one up. Let’s see if he was right.

20-something Lucy Moore arrives at Ravenswood Manor in 1931, on the outskirts of Tarrytown, USA. Lucy has been brought here as a maid to serve under the evil Ms. Crowne, the real-world equivalent of the wicked witch of the west. Crowne isn’t happy just making her workers depressed. She wants to make them les miserable.

After a tough first day, Lucy buddies up with another maid, Gertrude. The two are fast friends, which Crowne immediately picks up on. A day later and Gertrude has mystreruousy disappeared. Crowne says she left voluntarily during the night. But Lucy’s not buying it.

Before she “left,” Gertrude told Lucy about a special room in the manor. And after meeting Hale, the studly son of the woman Lucy looks after, Mrs. Dyer, the three are summoned to the special room, which we learn is a “ghost room” of sorts, where spirits are summoned. Right away Lucy is uncomfortable. She seems to have a special connection with the dead, a power passed onto her by her grandmother.

After connecting Mrs. Dyer with her dead husband, Lucy becomes a favorite of the woman, who insists to a furious Crowne that Lucy stay with her 24/7. Crowne attempts to undermine Lucy when she realizes her power is growing within the manor, but to no avail. The client, Dyer, likes Lucy too much.

With her newfound access, Lucy looks deeper into Gertrude’s disappearance only to discover a chilling truth – that Gertrude may not be dead or alive, but rather, stuck in limbo. Lucy will have to find her friend and set her free. But this will mean infiltrating Ravenswood’s most hideous secret – a secret that will change the nature of life as we know it.

This is DEFINITELY one of the better written scripts on the Black List. The writing is simple, descriptive, and, most importantly for a horror script, haunting. It feels professional right from the bump.

She waits, dwarfed by the soaring ceilings reflected in the shining marble floors. She takes a few tentative steps, surveys the sweeping grand staircase.

All is silent except for the soft POP of logs burning in the impressive fireplace. A YELLOW CAT watches from the shadows.

There’s also a sophistication to the dialogue that you don’t often see in the post 2018 Black List Era – in other words, dialogue that’s actually good.

“You are a queer one, Lucy. The girl who would refuse a job when so many are suffering. And now to be caught thieving and in hysterics in the middle of the night. The entitlement of it.”

Note the reversed nature of that final statement. Normally, that would go near the front of the sentence. “Do you understand how entitled you sound, Lucy? You’ve refused a job when so many are suffering.” But in real life, we don’t always think linearly. We come up with our thoughts on the fly, occasionally backloading sentences with points we realized we left out earlier. To write dialogue that reflects that is high level stuff.

Where this script is going to live or die, however, is with each individual’s preference regarding how they like their horror. If you like to have fun with your horror (Paranormal Activity), this script isn’t for you. If you like a giant infusion of drama in your horror (Let The Right One In), this is the script you’re going to be telling your horror buddies about.

Ravenswood puts on its “serious hat” from the outset. This script is about mood. It is about feel. Heck, you can practically smell the mildew within the manor, the novel-esque description is so thick.

It is both the script’s main strength and weakness. I dug it. I felt much more fear when we were placed in dangerous scary situations here (inside a garden maze with a headless gardener) due to how seriously the writer was covering the events. But it *did* come at the expense of being 40 pages into the script and still not knowing what the point of the story was.

This happens when you don’t add a clear goal. Which is fine. Horror movies are often powered by a looming sense of dread, of knowing that the monsters are coming. Being stuck in an ancient giant shadow-filled haunted house promises us many a spooky endeavor. But you can only milk that udder for so long before the reader starts demanding purpose.

Eventually, Enderle seemed to realize that Gertrude was the key to crafting any sort of narrative and therefore embraced the mystery of her having gone missing. This gave the script its coveted goal. But even then, the goal seemed to be stirred into other, less sexy, plotlines, such as the nonexistent romance plot between Lucy and Hale. That had real potential but the writer seemed to grow bored of it in real-time, as it had all but vanished (like a ghost) by the arrival of the first act.

The good news is, there were more good plotlines than bad ones. I was obsessed with the way Crowne pushed Lucy around, to the point where I would’ve been happy reading the entire script just to see Lucy stick it to her in the end, even if there hadn’t been any horror.

Speaking of, the horror imagery was good. Headless dogs. Headless gardeners. Limbless other animals and humans – all stuff Lucy kept seeing. It made for a nice mystery. We knew someone was lopping off body parts machete-style. But who was it? And why were they doing such a thing?

But the star of this script was always the writing. Even if I would’ve preferred more dialogue to make the read easier, I noticed a higher level of writing across the board, and it really made a difference in how the horror came across. Better writing better convinces us that we’re really there.

Take this simple line…

“A boy lies on a table, pale with death.”

Note how the line could’ve been…

“A boy lies on a table, dead.”

See the difference? The second line lacks any commitment to visually describe the moment. It gives us the cold hard facts and nothing more. The first example not only gives us an image in our heads (a pale dead body) but it’s also a more interesting way to say “he’s dead.”

It takes thought to write that way.

I have a feeling that this script will finish Top 10 when I do my annual Black List re-rankings. It’s pretty darned good.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your analogies should be reflective of the script’s setting. “Crowne has reached the foot of the stairs, appraises Lucy like a displeasing cut from the butcher.” This is a great analogy. Why? Because the analogy is rooted in the same setting that the script takes place in. A displeasing cut of meat from the butcher is something that would happen in 1931. I too often see writers using an analogy in this instance such as, “Crowne has reached the foot of the stairs, appraises Lucy like a drunk DJ at a wedding party.” In other words, the analogy is not time or setting appropriate.