Search Results for: F word

I want everyone who’s reading this post to stand up.

Go ahead. I’ll wait.

Are you standing?

Good. Now, I want you to start clapping.

And Hollywood? Take a bow. Because you’ve earned it.

Over these last three years, there was a strong belief that the theatrical box office was dead.

Even when mega-hits like Spider-Man: No Way Home, Top Gun: Maverick, and Avatar: The Way of Water, racked up gobs of money, those were still sequels. Audiences were coming “back” as opposed to coming “to.”

Would people still come “to” a movie?

It turns out they will. And this is such a great development because I was honestly scared. I thought theatrical film might really be on its way out. When a goofy movie like Barbie and a 3-hour historical film chronicling 200,000 deaths can both dip less than 45% on their second weekend after gigantic first weekend takes, that’s not just unheard of in 2023. That’s rare throughout the history of cinema.

To give you some perspective, Mission Impossible: Dead Reckoning dropped 65% in its second weekend. And that was off a much smaller opening than either Barbie or Oppenheimer.

So, what’s happening here? Why are we getting this amazing surge in moviegoing interest?

I get it when it comes to Barbie. Barbie isn’t so much a movie as it is a movement. A big part of that movement is that the movie oozes fun. You see the marketing and it makes you feel good. It’s bright. It’s goofy. It’s pink. It’s exactly what you want out of a summer film.

The movie that’s perplexing me is Oppenheimer. This is the kind of movie that you release in October and market it as an Oscar contender for six months. How a film with such depressing subject matter is performing so well in the middle of summer is something box office aficionados are going to be studying for years.

It’s funny, I overheard a couple of people discussing Oppenheimer at Trader Joe’s the other day and I couldn’t help but join in. They both loved the film. I asked them if they got bored after the bomb dropped and they said no. They liked seeing the fallout and how Oppenheimer dealt with it.

It’s something I’ve thought a lot about since the movie. Am I such a slave to structure that I’m unable to comprehend a movie that doesn’t use it in a traditional way? Usually, when the bomb drops, you get to the epilogue and roll those end credits.

In the interest of full disclosure, both those guys I talked to were clearly cinephiles. After we finished our Oppenheimer discussion, they were trying to sell me on an outdoor silent showing of Lawrence of Arabia. I told them, politely of course, that I’d rather take a long walk off a short pier.

In other words, I know cinephiles will love anything Nolan does. But regular moviegoers seem to like the never-ending story as well and I think I know why. When you like a movie, you don’t want it to end. So I suspect that’s what’s going on here. Instead of Mr. Obsessed Structure Guy (me) mechanically complaining that now that the bomb has dropped, the movie should end, they’re just happy this movie they’re enjoying isn’t over yet!

I’m not going to try any harder to figure it out. Regardless of whether I liked it, I’m very happy it’s doing well. Cause this is going to give studios confidence again. Studios with confidence are a lot more fun than studios without confidence. Because studios without confidence bank on boring safe IP. Studios with confidence take chances.

A question a lot of smart people are asking in the wake of this success is, “How do you create a movement?” A movement is bigger than a movie in that the audience becomes both customer and disciple. The experience isn’t just a passive trip to the theater. It’s a party.

This is particularly true with Barbie and it goes back to one of the oldest rules in the Hollywood book – one that they often forget – which is to GIVE US SOMETHING FUN. It may be cool to write something dark. But outside of LA and New York, audiences want something fun. They want to ESCAPE THEIR EVERYDAY LIVES for two hours AND FEEL GOOD WHILE DOING IT. And I’m not sure there’s ever been a more perfect option than Barbie.

I’ll never forget what Ted Elliot and Terry Rossio said when they were on one of the most lucrative screenwriting streaks ever (Shrek franchise, Pirates franchise, Zorro). They said they don’t understand why writers handcuff themselves with super dark material when there’s way more money to be made by writing fun stuff that people feel happy while watching.

Of course, this fails to explain Oppenheimer. But like I said. I’m not sure I’ll ever be able to explain why this movie is doing so well. There are several factors (Nolan is his own brand, the impossible-to-foresee Barbenheimer movement, one of the most star-studded press tours in history) that are making it hard to nail down.

But like I said – WHO CARES??!! All that matters now is that people are coming to see movies and they’re really excited about it. So suck it Netflix, TikTok, and video games. Movies are back, baby!

Shocker: It’s only three things.

As I come up on two decades of meticulously studying this craft, I’ve been thinking, what is my “theory of everything” when it comes to screenwriting? What is the “whole ball of wax” in regards to how to write a script that’s genuinely good?

I use that phrase “genuinely good” because the screenwriting world is packed with screenplays that range from bad, to not very good, to okay, to good. It’s actually kind of easy to write a good screenplay if you’re a working screenwriter. Cause you know all the tricks of the trade.

But how do you write something that’s genuinely good? Something that moves people?

I wanted to use today’s post to explore that question because a lot of writers are misguided in regards to how they approach screenwriting, shooting themselves in the foot long before they’ve typed a word of their screenplay.

There is not, nor will there ever be, a perfect formula for writing a great script and that’s because the world is constantly changing and the things that people like and accept and are interested in are changing with it. So something that was exciting six months ago might feel stale and uninteresting today.

There are also too many variables within a screenplay to be able to control them all. No matter how good of a writer you are, there are always going to be things that get away from you when you write.

There was a recent interview in Variety with the director of the infamous cinematic dud, Gigli, Martin Brest. He stated in the article that, during editing, he was looking at this scene that wasn’t working and he thought to himself, “I knew why this scene used to be in the movie and what its purpose was. I don’t have any idea why it’s in the movie now.”

That’s screenwriting in a nutshell. You have all these grand ideas but, over the course of writing a bunch of drafts, some of those ideas stick and others falter. Despite this, the remnants of every one of those ideas are still stuck in your script’s DNA, making your screenplay part story, part time capsule.

At times, it makes screenwriting feel impossible. Screenplays are like children. You can try to parent them. But, at a certain point, they want to become their own person.

So, in the pursuit of writing a great screenplay, you have to accept that there’s a certain lack of control. But that doesn’t mean you can’t set yourself up for success. And that’s what I want to talk to you about today. Here are the three most important things when it comes to writing a genuinely good screenplay.

CONCEPT

Field-testing a concept is probably the most important thing you can do in your pursuit of writing a great screenplay. And it’s the part of the process that the majority of writers get wrong. Especially beginner writers. Cause beginner writers assume that any idea they come up with is amazing.

The reason concept is such a problem is because the idea-inspiration process is antithetical to the idea-generation process. Most of us get inspired by something and want to write a movie about it. But just because it inspires us doesn’t mean anyone else would want to watch it. I may love the scientific exploration of algae. But would any sort of reliable audience be interested in a movie about algae? Probably not.

On the flip side, when you try to manufacture a concept, you may come up with a more technically marketable premise. But gone is the inspiration. And because you’re not personally inspired, the idea has no soul. It’s nearly impossible to write a great script if you don’t feel that soulful connection with it.

This is why you have to field-test concepts. You have to come up with ideas that both inspire you as well as contain marketability then run them by at least five people who you know aren’t trying to make you feel good (you know you’ve got a good field tester if they’ve told you one of your previous ideas was garbage). You need at least a couple of those people to be really excited about your concept. Preferably more than that. And five testers is just the minimum. Try to get as many opinions as you can.

I’d estimate that 80% of all screenplays written are doomed before the writer writes a single word because of a weak concept.

AN INTERESTING MAIN CHARACTER

There are three facets to the main character that you have to get right. The first is that we must make our main character interesting. A huge mistake writers make is they create a boring protagonist. This is rarely done on purpose. Most writers assume their hero is interesting simply due to the fact that they’re in the center of their story’s chaos for two hours. All these crazy things may be happening to your hero. But that doesn’t make *them* interesting.

So, look for ways to make your main character unique, charming, weird, have a big personality. Maybe a more succinct way to put it is to make them larger than life. Ferris Bueller was this untamed nuclear blast of energy. From Tony Stark to Deadpool to Daniel Plainview to Elle Woods to Juno. These characters are not wallflowers. They exert their force upon the world. As such, it is impossible for them not to impact us.

Next, we need a hero we can root for. That doesn’t mean they have to be likable. In fact, complex “unlikable” protagonists (Louis Bloom, Travis Bickle, Arthur Fleck) produce some of the best movies. But that complexity can never come at the expense of rootforabiality. Which essentially means, if one lacks likability, they must possess our sympathy. “Joker” is a masterclass in creating sympathy (getting bullied, takes care of sick mother, has a mental condition) for a genuinely unlikable person.

Finally, I’ve found that the best scripts have characters that are torn. They’re being pulled in different directions and the attempt to reconcile the chaos within them makes them compelling to read. Because even when there’s zero plot going on, there’s still something going on within the character himself.

A good recent example of this is Hijack, the series on Apple. Sam Nelson is torn. He just wants to get back to his family alive. And to do that, he’s willing to help the hijackers. But he, of course, also wants to protect the passengers. So he’s constantly having to make these tough choices regarding what’s more important – the safety of the passengers or himself.

And this doesn’t just have to be a dramatic thing. One of the most famous comedies of all time, Liar Liar, has Jim Carrey’s character in this never-ending battle of wanting to lie but having to tell the truth. There isn’t a single moment in the film where he’s comfortable. That’s a good indication that you’ve constructed a character with some genuine inner conflict.

A GREAT PLOT

Finally, you need to nail your plot. An understanding of the basics is essential here. You’ve got to have a character who wants something badly (their goal). You have to give that goal consequences if it’s not obtained (stakes). And you have to create urgency in the plot somehow.

You also want your plot to build. Every 15-20 pages has to feel bigger than the previous 15-20 pages. And you want to throw a lot of obstacles at your protagonist. It must feel like the universe is against them. Everywhere they look, there’s a new problem (see the second season of “The Bear”).

But the real trick with plot is that YOU MUST STAY AHEAD OF THE READER. 99% of the scripts I read, I know what’s going to happen in the next scene, five scenes from now, ten scenes from now. The weaker the writer is, the less they monitor where the reader is in relation to them. Which is how the reader gets way out in front of you, impatiently waiting for you to catch up.

You should always be asking yourself, “What is the reader expecting in this moment?” Sometimes, you should give them what they’re expecting. But you should also surprise them occasionally. Because if your reader isn’t sure what’s coming next, they’re a lot more interested in turning the pages.

Some recent movies where I didn’t know what was coming next were Parasite, Coda, Everything Everywhere All At Once, Us, Jojo Rabbit, Once Upon A Time in Hollywood, and Avatar: The Way Of Water.

Obviously, this is more difficult to do when you’re writing mainstream movies. But it’s definitely possible. Who saw that Liz’s father twist coming in Spiderman: Homecoming? And the great thing about throwing a twist like that in is, you place the reader on shaky ground. They no longer think they know what’s coming. Therefore, even if you decide never to include another twist again, you’re ahead of the audience just by the mere fact that they know one *could* come.

Obviously, having a unique perspective on life that informs your writing, giving it its own unique flavor, is going to improve all three of the facets I mentioned above. But this post is more for the writer who doesn’t have that game-changing unique voice. I want those writers to know that, with word work, they can still write a genuinely good screenplay.

There will never be a one-size-fits-all-formula for screenwriting. It’s why even AI will never master this craft. How can you master a moving target? But if you focus on the above three steps, you will give yourself the best opportunity to write something great.

What’s your personal “Theory of Screenwriting Everything?”

TV Pilot loglines are due tonight (Thursday) by 10pm Pacific Time!

“Pick me!”

“Pick me!”

Get those TV Pilot Loglines in! Here are the details!

What: TV Pilot Logline Showdown

When: The Showdown is on July 21st

Deadline: Thursday, July 20th, 10pm Pacific Time

What: send your title, genre, and logline

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

When we do these, “Why didn’t my logline get picked” posts, we usually do them after the fact. But I decided to change things up because we have a lot of TV loglines and I know all of you are eager to see if your entry made the top 5. So, at least this way, a few of you will know where you stand ahead of time. Let’s jump into it!

Title: THE LOCAL

Genre: Drama (one-hour)

Logline: A labor union president facing a tough re-election hires the estranged daughter of a hospital CEO to go behind enemy lines and help the union organize her father’s workforce.

Analysis: One of the tougher things about judging TV pilot loglines is that they’re rarely as concept-heavy as movie loglines. So I’m inherently aware that I’m not going to get “Source Code” in any of these pitches. With that said, your logline still has to leave an impression on the reader. There has to be some level of excitement on our end. And all that happens when I read this logline is I think, “That’s it?” There’s very little specificity to help this idea stand out from all the other TV shows out there. I mean, contrast this with the TV Pilot I just reviewed the other week with a group of rich people who hide out in a countryside mansion while they wait out the Black Plague. Note how specific that is. You feel like you’ve never seen anything like that before and that’s because you haven’t. Re-elections and unions and workforces… it goes right through one ear and out the other. The one specific element in the logline is the hospital CEO. But it isn’t woven into the presentation in a way that feels interesting.

Title: The Villainesses

Genre: Action/Comedy/Indie

Logline: In a small town where Villains are banished to live out the rest of their days, three female Villains must ban together to stop the other Villains from destroying the town. But the sociopathic Dictator that put them there, disagrees…

Analysis: It’s always a red flag to me when a logline contains unnecessary capitalization. Cause what I immediately think is, “If this person doesn’t even know that certain words shouldn’t be capitalized, how can I trust them to write a full story?” I know it seems trivial to some why industry people reject ideas. But, at the very least, your presentation should be spotless because too many people have come before you with bad presentation and taught those readers that their subsequent scripts are always bad. So the readers are just going off of past experience. Maybe your sloppy presentation is the one time where the script is still awesome. But most people aren’t going to give you that chance. And these are easy things to take care of with a quick logline consult ($25 – carsonreeves1@gmail.com). As for the idea itself, I don’t dislike the idea of villains being relegated to a, sort of, purgatory. And a showdown between villains in the town seems fun. But I don’t know why they have to be female villains who take on everyone else. Seems kind of random. And the final sentence about the dictator feels tacked on and inelegant, destroying any momentum that the logline may have had.

Title: Pwned

Genre: Action / Adventure

Logline: After being transported to a strange world where their earth-bound video game skills are manifestly real, four gamers use their respective skills of driving, shooting, athletics, and impersonation to join an uprising against a fascist politician in order to win their freedom and return home.

Analysis: So, with an idea like this, you run into a huge problem, which is that a great version of this concept has already been made, in Jumanji. I’m sure the writer would contend that his movie is nothing like Jumanji. But you have to look at things through the reader’s eyes. The reader is ALWAYS looking to compare movie ideas. It’s automatic. So you can’t really escape comparison if your idea is even slightly similar to another idea. And when you’re going up against a really great execution of that idea, your idea will almost uniformly feel like the “not as good” version. And that’s kind of what I felt here. Jumanji was just so fun because the characters got stuck in bodies that allowed them to play the complete opposite of who they were in real life. It was quite clever. Whereas this just seems more straightforward. Gamers who each have a particular skill team up inside a game to try and get home. It’s not a bad idea. But you don’t get points for writing “not bad” ideas. Your idea has to be something special. Despite this critique, I liked the title.

Title: The Wilderness

Genre: Dark comedy

Logline: A lonely, workaholic lawyer risks spending his entire life in prison after he chooses to harbor a mysterious fugitive with whom he’s fallen in love.

Analysis: I wanted to get one in here that had a specific “TV” reason for why it wasn’t picked. Can anybody guess why this didn’t make the cut? I’ll give you a second because I think it’s obvious. Ready? It doesn’t have enough meat on the bone to extend out into a full series. You’ve only got two characters, for starters. Most TV shows have a ton of characters because they need enough people to cut back and forth between to fill up a full season of television. On top of that, the central conflict is too simple. Someone is allowing a fugitive to stay with them. You have to put yourself in the eyes of the logline reader and ask, ‘what kind of show does the reader imagine from this logline?’ I’m imagining a guy talking to a fugitive in his house for 48 minutes a week. And the conflict isn’t even strong enough to support one episode of that. There was a show on Apple TV not long ago where Domhall Gleeson was holding his therapist (Steve Carrell) hostage. At least that setup had some genuine conflict. This feels too small time. I hope there’s more to this. If there is, it needs to be in the logline.

Title: Horror Adjacent

Genre: Horror/Comedy

Logline: Fed up with living next door to a haunted house, the Peevey family are desperate to move, but soon discover how hard it is to sell when your neighbor is a poltergeist.

Analysis: So, with this setup, we’ve at least got something marketable to work with. There are the beginnings of a fun idea here. My problem is a similar problem I have with half the loglines sent to me, which is that the end of the logline peters out. It doesn’t make sense. Why would the poltergeist in the house *next* door prevent you from selling *your* house? Maybe there’s a reason in the script. But we don’t have the script. We just have this logline. I see this mistake ALL THE TIME. The writer assumes we know just as much as he does. Honey, I got news for you. We only know what you show us. And I’m not making the logical connection of why a neighbor’s poltergeist won’t let you sell your own home. I could maybe understand why a poltergeist wouldn’t let you out of the house you both shared. But even then, I’m not sure why the poltergeist would want you to stay. That probably needs to be in the logline.

Props and thank you to the five writers in the line of fire today. You guys are brave for allowing your loglines to be put on blast. And just so you know, LOGLINES ARE HARD. Don’t feel bad. 99% of writers can’t come up with a good concept AND write a good logline. It’s hard.

The only reason I know how to do it is because I spent a decade having no choice but to write up loglines for the scripts I was reviewing. So if you want to practice, do that. Watch a movie and, afterward, write out the logline. Do that for every movie you see and script you read and you will get better. If the only time you ever write loglines is whenever you finish a script? You’re only going to be practicing loglines once a year.

Seeya tomorrow where our top 5 TV loglines will be revealed. And if you need help crafting your logline, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com. A basic logline consult is just 25 bucks.

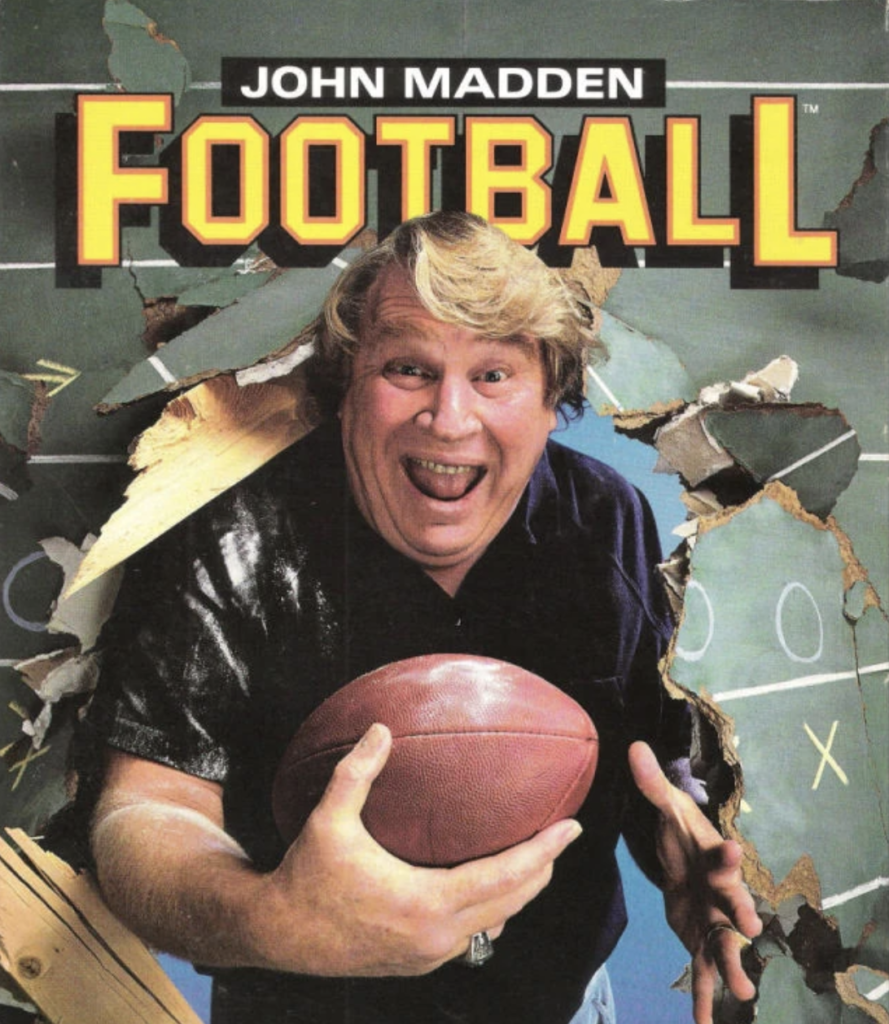

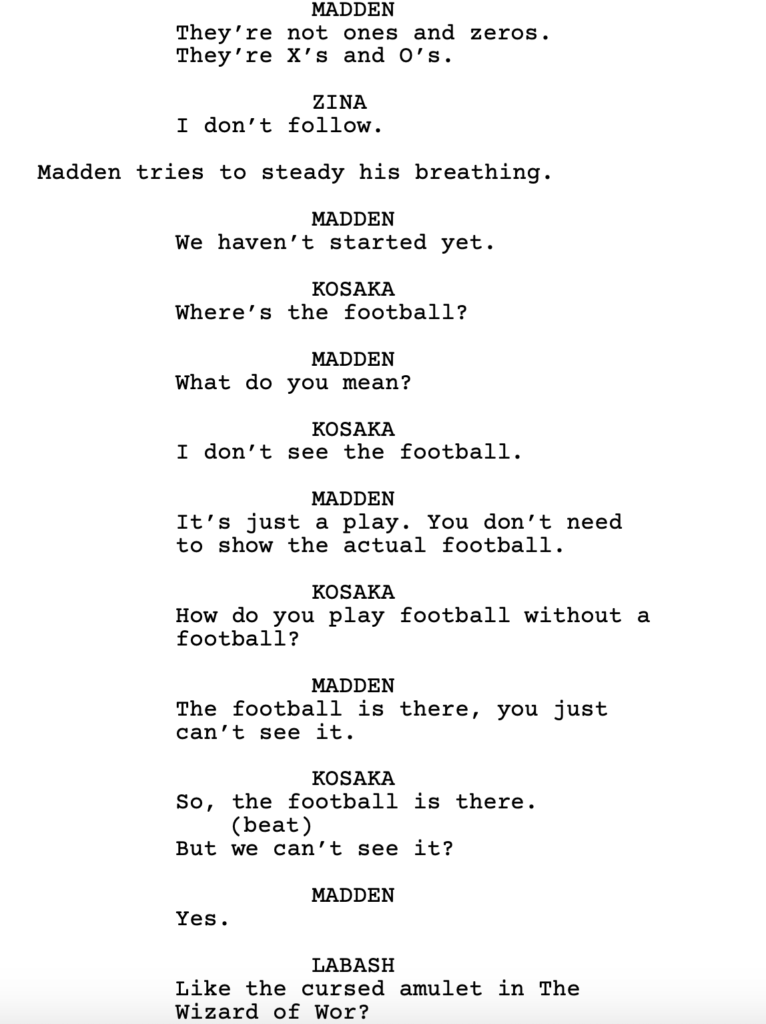

Genre: Biopic

Premise: (from Black List) After being forced into retirement by the Oakland Raiders, fiery former NFL head coach John Madden teams up with a mild-mannered Harvard programmer to rewrite his fading legacy by building the world’s first football video game. Based on a true story.

About: This script finished in the top 10 of last year’s Black List. It’s written by Cambron Clark, who has one previous credit for writing on one of those documentary dinosaur shows back in 2014.

Writer: Cambron Clark

Details: 123 pages

I’ve seen my fair share of concepts that sound like bad movies but none quite like this. Which is why it’s taken me this long to review one of the highest-rated scripts on last year’s Black List.

Here’s an idea for a movie. You know that football coach announcer guy? Well, he once made a video game. Let’s tell a story about that!

Ah, who knows? I would’ve thought Blackberry was a terrible idea and I loved that movie. Wait, no. Blackberry actually was a good idea because it was one of the most famous rises and falls of a company ever. What is this? A making-of-a-football-video-game movie? Have we officially run out of movie ideas? These are the kinds of scripts that make me understand why studios go all in on Marvel.

It’s the 1980s and John Madden, the coach of the Raiders, has just lost the last game of the regular season to Joe Montana and the San Francisco 49ers. The loss means the Raiders won’t make the playoffs so Madden is called in by the team owner and fired.

At just 42 years old, Madden is a retiree. He clearly doesn’t know what to do with himself. At first he tries to coach his 11 year old son, Michael, in Pop Warner football. But Michael doesn’t even like football. So you can tell where that’s heading.

Eventually, Madden runs into a dorky Harvard alum named Trip who just started a video game company called Electronic Arts, which he’s running out of his parents’ garage. Trip has an idea for the first ever football video game and he wants John to be the face of the game.

Madden ignores him at first but comes around, eventually. The two then need to hire programmers to program the game. The problem is, no programmers play sports. Much less football. So whoever they hire have to code a game they don’t understand. Which means Madden will have to teach them.

Madden soon gets word that his nemesis, Joe Montana, is also making a game! So now it’s a race. But Madden is wholly unprepared for just how challenging it’s going to be to teach a bunch of dorks football.

For 45 pages, I hated this script.

This thing is a cornucopia of dad-joke wordplay. Here’s a typical exchange, this one between Madden and his wife, Virginia. MADDEN: “I told you, it’s a temporary workspace. The guy who invented apples started in a garage.” VIRGINIA: “Jobs?” MADDEN: “Honey, for the last time, this is a real job.” VIRGINIA: “No. Steve Jobs.” MADDEN: “What does this Steve guy have to do with my job?”

If you like that humor, godspeed. But I’ve laughed harder at a puppy funeral. And it wasn’t just the dad jokes. It was the try-hard-ness of all the lines. There’s a line early on where Coach Madden tells one of his players, “I want you to hit him so hard Hertz stock drops.” This is supposed to be a clever line but I could read it 20 times over and still not understand what it means. That’s what I mean by “try-hard.”

Then something happened, something that made me understand the script. Or, at least, understand what the writer was going for.

A programmer being interviewed for one of the game-coding positions walked in in a cape. And Madden looked at him like he was an alien.

I realized, “ohhhhhhhh. This is a movie about the big alpha sports guy having to work with a bunch of geeks who have never played a sport in their lives.” I wish that would’ve been in the logline cause then I may have actually been interested in reading this! It just goes to show how much loglines matter. I see so many writers going away from what’s actually interesting about their ideas when writing loglines. Get a logline consultation (carsonreeves1@gmail.com) They’re just $25. Sheesh!

So why is this Madden-Geek matchup so great? Cause there is tons of comedy gold to mine from MISCOMMUNICATION. Put people who don’t speak the same language in a room and have them push towards the same goal… if you do that, you’ll come up with funny dialogue without even trying.

That’s when this script shined the brightest – when Madden was in the room with these dorks, who were all way more interested in Klorgan the Elf than an option shovel pass, trying to find a common language to get this game completed.

Another nice quality of the script was the relationship between John and his son, Michael. Michael, ironically, was way more into video games than football games. So when Madden started working with this video game crew, all of these guys were superstars in Michael’s eyes. So Michael then becomes a part of the crew, which allows Madden to connect with his son.

Unfortunately, whenever Madden strays away from those two zones, the script falls apart. It’s super dialogue heavy despite it’s aggressively unfunny try-hard nature. This is a script that wants to be “Air,” but the dialogue isn’t as sharp, clever, or purposeful. You get the feeling that the writer really loves his dialogue. And that’s not helping.

Because regardless of whether you’re a good dialogue writer or not, if you love writing dialogue, you have a tendency to do so just to show off. But that’s not how good dialogue works. Good dialogue doesn’t shine when a writer is showing off. It shines when it’s in service of the story. The dialogue is about that moment between the characters. Not that moment between the writer and the reader.

A random thing this script reminded me of was how interview scenes are comedy gold. They always work. Just the image alone of a frustrated Madden, who’s already seen twenty potentials, sitting there, tired and hungry, when a guy walks in IN A CAPE. That image alone made me laugh. And all the video game references the geeks bring up in an attempt to understand what Madden means — all of that was great.

Which, by the way, should be a major lesson to everyone here. When you come up with the right situation and dynamic, anyone is capable of writing good dialogue. But if you stray away from the fun dynamics and just try and generate good dialogue all on your own… I’m telling you, you better be one of the 25 funniest dialogue writers in the world if you expect that to work. The majority of us need the right situations to write good dialogue.

I’ll leave you with Madden trying to show the nerds football plays on a white board and all the nerds being utterly confused.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Lean into what works. Stay away from everything else as much as possible. What works here is Madden and the video game nerds. Madden and these kids trying to work together was comedy gold. But a good writer would’ve reazlied that he needed to start exploring that team-up way before page 45.

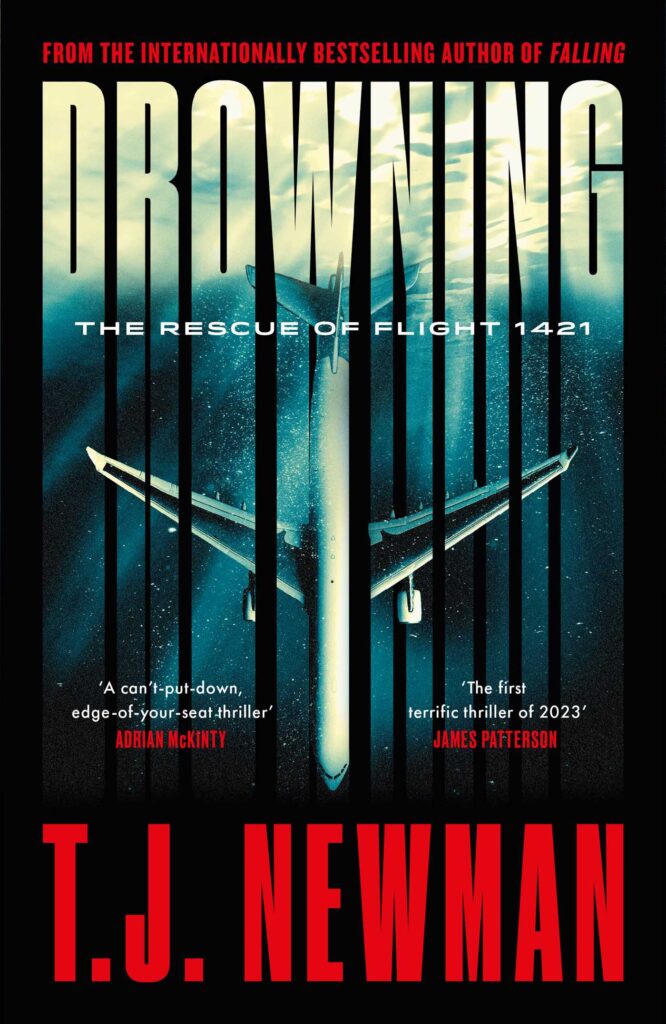

The big million-dollar sale from the flight attendant turned writer who’s become one of the hottest new names in Hollywood.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: Passengers must hope for a 1 in a million rescue after their plane crashes in the ocean and sinks, settling on an underwater cliff.

About: A couple of years ago I reviewed T.J. Newman’s first plane book, Falling, which also sold for a million bucks to Hollywood. Newman didn’t take long to capitalize on her buzz. Selling two books is always better than selling one. And staying in her lane was smart. If she would’ve tried to write a romance novel, she would’ve heard a lot of crickets. More planes, more dolla bills!

Writer: T.J. Newman

Details: 280 pages

I’m a T.J. Newman, the person, fan. This is a woman who spent 20 years trying to break into Hollywood. She got rejected by every publisher you can name. She represents resilience and persistence, two of the most critical qualities a writer must possess if he/she wants to succeed.

Those qualities can not be underestimated. Everyone talks about the sexy stuff that a writer needs. They need “voice.” They need to have their pulse on the people, knowing what concepts sell. They need to be a whiz with dialogue and plot and structure and pacing.

And you do need all those things.

But they mean nothing if you’re not resilient to rejection. LOTS of rejection. And if you’re not persistent. You gotta be able to keep trying. Not let the many negatives that come with the pursuit of art get you down.

Now, do I like T.J. Newman, the writer? That’s a more complex question. I thought her first book was okay but straightforward. It didn’t surprise me enough. I’m someone who needs a script to give me what the concept promised but also keep me on my toes. Let’s see how Newman did in those departments.

Engineer Will and his daughter, Shannon, are flying from Hawaii to the mainland where he’ll drop her off and then head back home. Unfortunately, Will doesn’t have a home to head to because he and his wife, Chris, an underwater construction director, are separated.

Will’s plane starts losing altitude just several minutes after takeoff due to an engine blowing up. Not long after that, the plane is in the ocean. The pilot, Kit, was successfully able to pull a Sully. But unlike the Miracle on the Hudson, the fiery engine is causing all sorts of issues outside the plane.

When everyone tries to head out to the water, it’s Will who screams at them to close the door. The fire is about to get a lot worse and anyone who’s out on the water will get roasted. He somehow manages to convince Kit of this theory and she closes the door.

Not long after that, the plane sinks to a little cliff a thousand feet underwater. Without getting too complicated, the plane is tilting over the cliff and slowly taking in water within its cracks. Will estimates they have about six hours of oxygen.

Cut to topside where Chris, Will’s wife, who’s currently on a job, hears about what happened and rushes over to join the Navy and help out with the rescue. The Navy wants to pull the thing up to the surface by its tail. But both Chris and Will use science to explain how that dumb plan will actually kill everyone.

Chris has a better plan that involves a slick rescue vehicle. Only problem is that the vehicle is broken. So she’s going to have modify the rescue and pull off a miracle. Will she do it all before the dozen people in that plane run out of air? Tick-tock-tick-tock-tick-tock.

If you want to write a book – or a script – that sells for a million dollars, you can’t go wrong with a big flashy situation and an ultra-tight timeframe.

I don’t think the average writer realizes just how powerful timeframes can be in storytelling. If you tie a 6 hour timeframe to a life-or-death situation, it’s hard for a reader not to get pulled in by that.

This movie doesn’t play the same way, for example, if they’ve got a full day of air. I see this problem a lot. I just gave a note to a writer in a consultation who had a 90-day timeframe on their story. 90 days is a long time for anything! I suggested 1 month.

If the reader doesn’t feel the urgency of the situation, you’re missing out on a major dramatic anchor for your story.

So the setup here was good. I was pulled in.

And then the writer did something that nearly killed it for me. Yup, we’re talking about DKB (Dead Kid Backstory). I know some of you like it. You’re all wrong. I am here to tell you it is a failed dramatic device 99% of the time any writer tries to execute it. Are you really betting you’re that 1%?

Here, Chris, Will, and Shannon have a DKB. Their other daughter died in a pool accident six years ago. Look, it wasn’t the worst use of DKB I’ve seen. But the big reason DKB doesn’t work no matter how much you want it to is because it’s lazy. It’s the laziest form of emotional manipulation a writer can use. “Love my characters cause their child died!” It’s desperate.

And I know that it’s a lazy choice because it’s not even the only time Newman used it in this novel! There’s ANOTHER character with a DKB. Which tells me that the writer is only willing to pick the low-hanging fruit when it comes to her backstories.

So this put me back in a neutral place. Strong opening. Weak backstory. Back in the middle.

What you’ll hear most writing teachers say is that there’s the external story and then there’s the “real” story, which amounts to the human story at the center of your script/novel. The external story is a plane settling on the bottom of the ocean. But the real story is about this family reuniting.

The problem is I’m not sure whether Chris coming to save Will and the two having jobs that are perfectly suited to figuring out this problem is serendipitous or coincidental. One is good for storytelling. The other is bad. And it did feel a little too perfect for me. That this man’s wife just happens to be the only person in the world who knows how to save this plane.

But I get what Newman was doing. She didn’t want this to be a nuts and bolts rescue. She wanted an emotional core to the story. A family reuniting is, technically, the right approach to these things.

I’m just not sure I ever cared that much. That’s the problem with making lazy choices (DKB). They affect how much you care about the characters involved in that backstory. Cause you know you’re being aggressively manipulated. You can see what the writer is trying to do. And that’s when the suspension of disbelief breaks.

Also, there’s a difference between choosing sad backstories and choosing depressing backstories. A sad backstory is one where we can tell it hits the characters hard but we can still distance ourself from their experience. A depressing backstory feels lousy to everybody. You’re telling about dead kids? Why do I want to read about dead kids in a movie about a plane rescue? That’s just depressing s—t. I don’t read thrillers for that.

In case you hadn’t noticed, DEAD KID BACKSTORY BOTHERS ME.

Despite this, the story moves fast. And the scientific stuff seems surprisingly well-researched. It felt real. What TJ Newman did well is that she truly made you wonder how they were going to save these people. Cause there was no clear solution. Too many writers make it easy to figure out how they’re going to solve the big problem. I didn’t know here. And I liked that two of the plans failed, leaving them without any options left. NOW what are they going to do? I genuinely didn’t know.

So, much like her first book, I thought this was okay. It was like a less good version of Ron Howard’s Thai cave rescue film. But it’s also a much flashier concept than that. So it could end up being a good movie. And I will always champion when studios make an original film.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Here’s a dialogue trick. Let’s say you have to dish out some backstory about a character. The way you normally do this is to have a second character ask your character questions about themselves. Then our character answers them and, in the process, shares their backstory. The mistake writers make in these scenes is focusing on our character explaining his backstory. Writers do this to make sure that all the information about the character’s backstory gets to the reader. For that reason, these scenes never work. They’re written to a disembodied audience rather than someone in the story. To solve this, FOCUS MORE ON THE PERSON ASKING THE QUESTIONS. In other words, make them genuinely curious. Make them WANT THE ANSWERS. Cause if the person asking the question genuinely wants to know the answers, then our character will be speaking more to him than to the reader. And that’s how you write genuine backstory dialogue in that circumstance.