Search Results for: F word

Genre: Action

Premise: Ethan Hunt must battle his biggest threat yet – AI!

About: July was the summer’s biggest movie month. Indiana Jones, Barbie, Oppenheimer, Mission Impossible. Who was going to make it out alive? Who would fall? Cruise and McQuarrie’s latest, a labor of love that, at one point, had Cruise famously terrorizing his crew over broken Covid protocols, has finally arrived. It pulled in 56.2 million for the 3 day weekend and 80 million for the 5 day. A bit of a surprising choice at screenwriter for McQuarrie as he handpicked a guy named Erik Jendresen, who has not written anything of note. And now he’s got a Mission Impossible credit under his belt. Oh how your fortunes can change in this business. That big job that’s going to change your life is always right around the corner.

Writer: Erik Jendresen and Christopher McQuarrie (based on show by Bruce Geller)

Details: nearly 3 hours!

The Mission Impossible franchise continues to confuse the world with its box office reception. It’s never quite a hit but it’s never quite a bomb either. Still, I can’t help but feel like this latest iteration needed to do better in order to justify the continuation of the franchise.

56 million dollars for a weekend haul is not a great showing in 2023. Then again, defenders of the film will point out that Mission Impossible is not a domestic film. It’s a global film. And that’s where it will make its money.

I hope it does. Tom Cruise is basically the last actor opening movies all on his own. Once we lose that, it’s blue beetles all the way down!

Ethan Hunt is tasked with a mission (should he accept it). He’s got to get a key. This special key, which has two halves, has a mystery purpose. Nobody knows what it opens. Or even where the lock is that it opens. But that’s not of Ethan’s concern, he’s told by Recorded Voice Guy. Just get the key.

Meanwhile, the government is dealing with an increasingly unpredictable new AI that has, in their estimation, become sentient. The AI recently destroyed a Russian nuclear sub and an operating thesis is that the US could be next.

Enter Hunt, who has to get the second half of the key (he got the first half in the Arabian desert) from a mystery seller at an airport, all while being chased by the CIA. Things take a turn when a low-level pickpocket named Grace steals the other half of the key and now Ethan is forced to team up with her.

This begins a cat-and-mouse game between Ethan, Grace, the CIA, AI, and even Ethan’s own boss, which takes them across the globe and concludes on a runaway train. Along the way, Grace will have to decide if she wants to level up to become a true spy, and Ethan will have to… well… continue to achieve the impossible.

Midway through my Mission Impossible viewing, it occurred to me that I wasn’t sure what I actually look for in a Mission Impossible movie. When I watch a Star Wars movie, for example, I’m looking for insane imagination. I’m looking for new revelations into the lore. I’m looking for great characters. I’m looking for an awesome lightsaber battle. And I’m looking for two imaginative set pieces that blow me away.

I think with the modern-day Mission Impossibles – the ones written and directed by McQuarrie – I’m looking for a better written blockbuster than most (since McQuarrie started out as an Oscar-winning screenwriter). I’m looking for one really clever set piece. And I’m looking for one visually jaw-dropping set piece. I think that’s exactly what McQuarrie attempted to give us. So how did he fare in each department?

Let’s start with the script. The script is very much a Mission Impossible script. There’s the McGuffin of all McGuffins – a key that opens something. The key, is of course, split in half, which gives us an opportunity to extend the plot out (cause you’re looking for two things instead of one).

I’m not going to say it was a bad McGuffin. But one thing that really bothers me in McGuffins is when the McGuffin isn’t relevant. It’s just a means to get characters to run around. Ideally, you want your McGuffin to be more than a McGuffin. You want it to to matter! Like R2-D2. That McGuffin not only held the plans to the Death Star. But it was, in itself, a great character! These McGuffins today are just cool-looking keys?

But let’s move on to the big story gamble in the script – incorporating an AI villain. As others have pointed out, a faceless villain is risky because you don’t have a face for the audience to root against. You don’t have the potential for a true villain showdown. That’s not to say there aren’t bad guys in this film. But the bad guys here are not the *true* threat. The true threat is the AI and AI’s don’t have a personality to get you emotionally revved up about.

This was a surprising choice, I’m not going to lie. Stanley Kubrick proved 60 years ago that an AI could be a great villain, with HAL. I think McQuarrie’s plan was to terrify us by giving us a villain that didn’t have a personality OR a conscience. It was a giant cold piece of code. If something doesn’t have a personality, a conscience, an ability to be reasoned with – isn’t that the scariest villain of all?

Maybe.

But it sure didn’t help the film. This movie badly needed someone to root against. And I’ll tell you why. You’re using too generic of a movie formula to be able to skimp on personalities. Your characters are the only things that are going to make a movie like this stand out. Otherwise it’s just guns and chases.

Take John Wick 4, for example. That crazy fat club gangster guy was a true personality. He brought a larger-than-life personality to the proceedings which helped make up for the fact that it was a movie full of generic guns and fights. Same thing with the blind assassin. Personality.

No personalities hurt Mission Impossible. You saw the culmination of this in that final train set piece. It was a good set piece but where was that emotional catharsis that comes from killing Hans Gruber, a guy we’d grown to detest? Not having that turned a potentially great sequence into one that was just “good.”

Overall, I was hoping for a more original story. This story was more of the Mission Impossible same – create a template for set-pieces and don’t give us a lick more. I’m such a story guy that I need more than that!

But let’s talk about those set pieces.

The two highlights were the airport set piece in the middle of the movie and the train set piece at the end.

The airport set piece is more of what I’m looking for in a set piece. Like I talked about on Thursday, I want that contained (we’re contained to an airport) clever set piece with a clear goal and a lot of obstacles and that’s exactly what we got.

BUT!

I think McQuarrie tried to do too much with it. There were some cool ideas here about hacking being used to change facial recognition so that the CIA attempting to locate Ethan Hunt results in them continually following the wrong guy. But once Haley Atwell’s, Grace, shows up and steals the key from the mark, things start getting confusing.

We’re dealing with Ethan trying to find a passenger with half the key. Ethan’s got the other half. He can’t buy the second half from this guy so he has to sell him his half instead and then get on a plane with him where he will, conceivably, steal the full key back at some point, after he’s gotten more information.

But Grace, a lowly pickpocket, takes the half-key from the mark instead and now Ethan’s following her. And, oh yeah, Benji is chasing down a nuclear bomb in the baggage claim that our AI villain somehow constructed that can only be disarmed by six riddles. The CIA is trying to locate everyone. With so many set piece storylines, I’d forgotten why we’d come here.

Guys.

Again.

The Langley white room hack scene from Mission Impossible 1 is such a simple scene. Why are we trying to make this sequence as elaborate as possible? For us to enjoy what’s happening, we must UNDERSTAND what’s happening. And the deeper you bury your set piece in storylines, the harder it is to keep track of things.

I would still say I enjoyed the scene, though. It was the most cat-and-mousy moment of the script and the cat and mouse stuff is what I enjoy most from the Action/Spy genre.

Moving on to the final train set piece.

The train set piece is preceded by the big stunt of the film, which is Tom Cruise jumping off a cliff on a motorcycle and then parachuting onto a moving train. The downside of promoting each Mission Impossible super stunt is that, by the time you see them, your expectations are sky high. So I was a little let down by the actual stunt itself.

Cause I think the stunt only encapsulates jumping off the cliff and opening the parachute, right? It would’ve been REALLLLLLLLY cool if the stunt included that AND timing a parachute drift down and landing on a moving train.

I know! You’re saying, “Come on, Carson. You can’t actually expect them to do that.” Well, I kinda can. They’ve marketed Cruise as the super-stunter. So I’m expecting him to do impossible things. One quick hop off a cliff… I’m just not sure that’s enough for me.

Anyway, once we get onto the train, things get a lot more interesting. I definitely felt that this was the best sequence in the film. And kudos to McQuarrie because there have been a million train scenes already. So it’s hard to make one that stands out. I liked the use of the old school Mission Impossible masks in this sequence. And I definitely liked that train falling into the ravine one car at a time.

The biggest surprise of the movie for me was Hayley Atwell. She was fun. When I saw her first come on screen, I thought, “Wow, Hayley Atwell has had some work done. I guess she’s fallen into the Hollywood trap.” But then I realized, no, she just got in amazing shape! Which made her face look a lot more chiseled. It was quite motivating, to be honest. It shows how much you can change your look just by getting in shape. Put down those donuts, screenwriters!

And she had great chemistry with Tom Cruise, which is no doubt why they cast her. Plus, I liked the idea of bringing in a character who’s in way over their head and forcing them to keep up. Grace’s car chase scene was a cool sequence.

Speaking of that sequence! I’m always about finding new spins on car chases. Handcuffing Ethan and Grace together and throwing them into a car chase was a really creative twist. It forced them to have to be on certain sides of the car, which required the less competent driver (Grace) to drive, which was fun. And I loved when they tangled up their arms to allow Ethan to drive, creating a handicap for Ethan, which of course made the chase harder, which is always what you’re trying to do – make things harder for your characters.

But the villain, man! There’s no true villain here!

If you are going to make that commitment to AI as your villain, I would’ve liked them to commit to it. It seemed like AI was there for McQuarrie when he needed it and gone when it was inconvenient. For example, AI is, conceivably, always listening to us. If there’s an Alexa device in the room, or a computer, or a phone, AI can hear you. Cause AI is everywhere.

But there were plenty of scenes – such as the airport scene – where nobody was worried about that. Or remember that scene early in the movie where they’re debriefing everyone on AI and Hunt throws those green stink bombs. Why weren’t any of them worried about AI listening to them there?

If you want to truly TRULY explore the dangers of a dangerous AI, let’s get into the thick of things. Let’s not keep everything surface-level. Particularly because you’ve already got a faceless villain. You need to make up for that lack of personality somewhere.

When it comes to whether I endorse this movie or not, I’m on the fence. It’s fun. But it’s also generic. Cruise and Atwell are good. But nobody else really stands out. In the end I’d say it’s entertaining enough. I’m a sucker for a fun summer moviegoing experience and I think this satisfies that need.

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: More is rarely more. In screenwriting, less is usually more. There is no question in my mind that this movie becomes a lot better if they cut out the whole “obtain the first half of the key” stuff. Nobody cares about this Ilsa woman. The Arabian desert sequence was weak. If you nix that and, instead, start with them prepping for the airport exchange, this whole movie changes for the better. It feels faster. It MOVES faster. And I think with a zippier run-time people would leave the theater feeling more charged, which would improve word-of-mouth. As it stands, there’s no reason at all for this movie to be 3 hours.

And the power of containing your set pieces!

This weekend, I’ll be seeing the latest Mission Impossible movie. These movies have become known for their set-pieces, specifically the ones that Tom Cruise does himself. Tom Cruise scales a real skyscraper. Tom cruise HALO jumps out of a plane. Tom Cruise takes off on the side of another plane. Tom Cruise drives off a cliff on a motorcycle.

But Mission Impossible has plenty of other big set pieces, such as helicopters chasing trains through tunnels. Motorcycle racing through the hearts of European cities.

And I’m here to tell you that all of these set pieces suck.

Well, maybe “suck” is a strong word.

But none of them truly engage the viewer. They’re just throwing a lot of movement at you and hoping you say “Wow.” Some people do say “Wow.” But it’s always an empty “Wow.”

I don’t just blame Mission Impossible for this issue. I blame all movies. Specifically Hollywood movies. They have destroyed the set piece mainly because they have no idea what actually engages a viewer anymore.

They think having a million things going on onscreen at once with as much action as possible is the way to go. And they’ve been doubling down on that strategy for over a decade now. They ask, “How can we create MORE movement? MORE wows?”

In the process, they’ve lost the thread.

They’ve actually lost it so bad that it’s ruined 99% of big-budget studio films.

What Hollywood has forgotten is that it isn’t the big flashy action set piece that gets audiences excited. It’s the contained smartly-crafted set piece that audiences remember for the rest of their lives.

There’s no better example of this than the file copy hack at CIA headquarters in the first Mission Impossible. It’s the famous scene where Ethan Hunt is lowered down into the white computer room and must steal a file from an off-line computer without tripping any of the advanced alarms that have been put in place.

How I do know this is the best set piece?

Cause when I say, “Mission Impossible,” what is the first image that comes to mind? It’s that scene. And that’s because *that* scene is *that* good.

But why is it good? Why is it more memorable than all of the garbage set pieces that these superhero and Fast and Furious and Star Wars movies keep pumping out?

For starters: IT’S SIMPLE.

I cannot emphasize how much better your set piece will be if you make it simple. Dude is lowered into a room and must hack a computer.

THAT’S IT!

That’s the scene.

There will not be a single person in the movie audience who will not understand what’s going on in that scene.

Contrast that with Dr. Strange when Strange and that America chick were running around on floating virtual objects. Did anyone know what was happening there? I didn’t.

That’s the mistake the studios are making. They’re creating these big visually wild set pieces that don’t make a lick of sense. And then young writers see these and they think, “Oh, that’s the way you’re supposed to do it.” So then *they* write big awkward CGI scenes. Those scenes are then put in the next superhero movie. And it becomes a vicious circle.

Which is why nobody knows how to do this anymore.

So, for starters, when you’re trying to construct a set piece, don’t think big first. Think SMALL first. Small is much easier to understand. It will require way less geographical orientation. And it will allow you to come up with a set of simple rules that you can then play with to make your set piece as dramatic and suspenseful as possible.

Which is exactly what the CIA computer hack scene in Mission Impossible does.

It’s a tiny room. That’s our set piece. That and the vent.

Once you have your contained space, set up the rules of the set piece. In this case, the room is the most sophisticated room in Langley. It detects weight changes, sounds, even heat.

This is where the fun starts. You have these challenges, such as, we can’t walk in because it will detect our body weight. Okay, so I guess we have to suspend Ethan and lower him from above. How do we do that? Well, there’s this vent here. Okay, but how do we create a suspension system within that small space that’s going to be reliable?

Notice how even before we’ve gotten to the set piece, we’re already becoming invested in it. Nobody does that anymore. They just throw us into some wild mid-city chase with a bunch of characters we barely know.

Then, once we get to the set piece, we can continue to have fun with the rules we’ve set up. For example, if Ethan so much as touches the floor, it will trigger the weight sensor and they’ll be caught. So, one of the first things that happens is that the cords slip and Ethan falls quickly towards a collision with the floor, only to be caught at the last second.

I’ll never forget the collective gasp from the audience in my theater when that moment happened. That’s when you know you’ve created an awesome set piece.

The rules are so perfectly set up in that scene that there’s a moment where Luther has a bead of sweat that’s in danger of dropping from his nose down into the room and hitting the floor, and we’re all on the edge of our seats hoping it doesn’t happen.

Give me one Marvel set piece in 25 freaking films that achieves that. You can’t!

If you want to upgrade your set pieces, do everything I just said. But there’s one additional thing you can do to bring it to the next level: ADD AN EMOTIONAL ELEMENT – something between the characters that gives the scene a little extra oomph.

Take The Matrix for example. One of the great set pieces in that film is Neo fighting Agent Smith in the subway. Once again, contained, right? Simple, right? But, in addition to the Mission Impossible scene, we have some history between these two. Agent Smith was the bully following Neo around in the Matrix. And Neo is someone Agent Smith needs to dispose of if he’s going to execute his plan.

The irony here is that the Wachowskis were hoping to get Will Smith to star in The Matrix so they’d have this giant budget, which would have allowed them to write much bigger and flashier set pieces. But when they had to settle for Keanu Reeves, they had to rethink all their set pieces which made them into what I’m telling you to do here.

Contained. Simple.

The dojo fight, the lobby gunfight, even Morephues rescue is contained to an office in a skyscraper and then a helicopter right outside.

I don’t think I need to remind you what happened when the Wachowskis got all the money they wanted for the sequels. Big bombastic set pieces that didn’t hold a candle to anything that happened in the much smaller first film. If that isn’t proof that smaller more contained set pieces are better, I don’t know what is.

Getting back to Mission Impossible, a few years ago we had that well-received bathroom brawl – the one where Henry Cavill’s character and Ethan Hunt kept pummeling people who came into the club bathroom.

That’s a contained scene. So why isn’t it as famous as the Langley hack scene? This is your last lesson so pay attention: BECAUSE THE HACKING SCENE HAD STAKES. There was this long build-up towards it, which, on its own, created stakes. Since we had so much personal time invested in it. But even still, they needed something vital in that computer to execute the bigger plan.

The bathroom scene was fun but it was haphazard. There’s nothing truly on the line here. It’s just people beating each other up. So when you create that set piece, make sure there’s something big on the line. Or else, even the best execution of the scene isn’t going to grab the audience and shake them.

I hope writers take this to heart. It’s one of my crusades as a teacher of screenwriting. I see so many movies making this mistake and they’re just creating this garbage because of it. When it comes to set pieces, it’s always better to be think contained, to think simple, and to be clever. Only go big as a last resort.

Good luck!

Genre: TV Pilot – 1 Hour Drama

Premise: During the Black Plague, a group of rich Italians head off into the countryside to party out the plague in a beautiful villa.

About: Word on the street is that Bridgerton was so big for Netflix that they wanted more period stuff. Enter Jenji Kohan, creator of Netflix’s famed, “Orange is the New Black.” Let’s just say that Jenji’s version of “fun” is obviously a lot more complex than everybody else’s version of “fun.” Although Jenji is the producer, the creator of the show is Kathleen Jordan, who wrote Teenage Bounty Hunters.

Writer: Kathleen Jordan

Details: 61 pages

Tony Hale will be playing the hapless Panfilo

Tony Hale will be playing the hapless Panfilo

I’m reviewing today’s pilot to remind everyone that Pilot Showdown is coming up!!! Send in your pilot logline along with your title and genre. The best 5 pilot loglines will compete against each other with you, the readers of the site, voting for the best. Whoever wins will get their pilot reviewed the following Friday. There’s obviously an appetite for this because I’ve been getting a lot of pilot loglines sent in. It’s going to be a dandy.

What: TV Pilot Logline Showdown

When: July 21st

Deadline: Thursday, July 20th, 10pm Pacific Time

What: send your title, genre, and logline

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

As the world attempted to decipher why brooding Timothy Chalamant was cast in the role of one of the most charismatic characters in history, I reminisced about when Orange is the New Black first hit Netflix. Along with House of Cards, it felt like a new era in television had emerged, rivaling when Jackie Gleason first appeared on TV.

If you remember, this was the first time in history that an entire season of television shows was offered at once.

It was a strange decision that streamers have, since, backtracked on, at least for their larger shows, as it practically begs people to sign up for a month, binge the new show, then ghost the service.

The practice also inadvertently birthed a new storytelling format – the “movie” TV show. Narratives were now being designed like films, to build over an entire season, as opposed to ebbing and flowing, delivering standalone experiences you could enjoy without having kept up with the series.

My jury’s still out on this format. I don’t think it quite works yet. But writers continue to play with it and learn it. Hopefully, we’ll figure it out because I do like the idea of one long enjoyable narrative.

It’s 1348 in Firenze, Italy. Peasant Licisca is a handmaiden for the worst woman in the world, Filomena, a sort of 1300s version of Paris Hilton. Everything revolves around her. Especially now that her entire family has died from the black plague. Well, except for her dad, but he’s on his way out.

Filomena is visited by a messenger who invites her to Villa Santa at the behest of Leonardo, a really rich bachelor whose plan is to have everyone stay at his villa for one long party until this whole black plague thing goes away.

Filomena ditches her barely alive father, taking Licisca with her, believing she will finally find the husband she so desperately covets. However, along the way, Filomena and Licisca get into a fight that spills out of their carriage and near a bridge where Licisca inadvertently pushes Filomena to her death.

This is when Licisca gets a brilliant idea. Nobody at this place knows what Filomena looks like. So SHE’S going to be Filomena!

Once she gets there, we meet the rest of the crew. There’s the studly doctor, Dioneo, who Licisca immediately crushes on. Dioneo is the doctor for the hapless Panfilo, an ugly dork of a man who can get sick at the drop of a hat. There’s the religious horndog, Neifile, who, unfortunately, married the very gay, Panfilo. Translation: she’s not getting any.

But the biggest surprise is that the two elderly caretakers of the villa, Sirisco and Stratilia, are containing a giant secret. Their master, the owner of the villa, Leonardo, is dead of the black plague. They buried him. If Leonardo is dead, neither of them have masters and they’ll be cast off into homelessness during the worst plague in history. So they must do everything in their power to make sure that their secret never gets out.

What a weird idea.

What a weird FUN idea.

I love a bit of irony in a concept. But the thing with irony is that there are weak versions of it and clever versions of it. This definitely lands on the clever side. One of the things I judge an idea on is how easy it is to come up with. And I’ve never read a single idea that was anything close to this. It’s truly unique. And clever as s—t.

Cause think about it. We’ve seen a bunch of rich people living in these mansions with servants before. That format has been done to death. But this puts an ENTIRELY new spin on it and one that opens up all sorts of fun ideas that the writer takes advantage of.

For example, in what other version of this idea could you kill off the villa owner and everyone just goes along with it? In what other version could your heroine believably take on the persona of a rich noble?

And then you have these interesting relationships. Like this guy who just walks around with his own personal doctor everywhere. As it so happens, the patient is a disgusting rat of a man and the doctor is the most handsome man in the world. So wherever they go, even though he’s the wealthy and important one, everyone falls in love with his doctor.

I think that’s another thing that sets this pilot apart. The writer put a ton of effort not just into the individual characters, but the main relationship that each character had. One with their maid, one with their spouse, one with their doctor, the two caretakers. There are these interesting pairings that lead to a bunch of great dialogue and fun scenarios. It’s almost like teams, which adds a different dynamic when the teams talk to other teams.

I personally think this is going to be too weird for a lot of people. But if you like weird TV and writers that take chances, you’re going to absolutely love this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Exploit your premise! Identify what’s unique about your premise and make sure there are characters and plot developments that specifically exploit it. This is a show about rich people vacationing in a big villa while waiting out a plague. So the writer killed a character off and had our hero impersonate her. The writer killed off the villa owner, leaving everyone waiting for a guy who’s never going to show up. Most writers wouldn’t have thought that deep. They would’ve got Licisca and Filomena to the villa together. Leonardo would’ve still been alive. The lazy writer thinks in terms of their original idea and not in terms of, “What does a *lived in* version of my idea look like?” The *lived in* version is always dirtier. Things have already happened inside the lived-in version to muddy it up. So make sure to think beyond that very first concept that came into your head.

Genre: Drama

Premise: (from Black List) After a young, newly widowed janitor in a small mining village is unexpectedly elected Mayor, she navigates a new relationship with a mysterious man from the city and tries to determine how to use her new position of power to confront the corruption that has plagued the town for years.

About: This script finished pretty high on the Black List last year, with 13 votes. The writer has produced a few small projects and has mainly worked in short films.

Writer: Brendan McHugh

Details: 92 pages

Dakota Johnson for Sasha?

Dakota Johnson for Sasha?

Every once in a while, you read a logline on the Black List and you say, “This is such a bad logline that the script must be amazing.” In other words, your script would have to be great to overcome this logline.

This has happened a few times before – where I’d see a terrible logline that was summarizing an equally terrible concept but then something about the writer’s voice or the characters in the script blew me away. It doesn’t happen often. But it does happen. Will it happen again today?

Sasha is a maid in a small corrupt mining town that’s basically run like the mafia by the town’s mining czar, Pike. Technically, the town has a mayor (who’s Sasha’s boss), but he’s a mayor in name only. His sole duty is to do what Pike tells him to do.

Sasha has a particularly combative relationship with Pike due to the fact that her husband recently died in the mines and instead of Pike giving her his life insurance, he tells her that her husband was liable, so there’s no insurance to pay out.

And, oh yeah, Sasha is eight months pregnant.

When Sasha is at her lowest point, a cool-as-a-cucumber surveyor named Jack rides into town on his motorcycle. He asks Sasha out on a date and she says yes. The two have a great time.

The next day, the mayor tells Sasha that reelection is coming up and the election is not official unless he has an opponent so she has to run against him. She doesn’t want to but he forces her to sign the papers. When the miners (who are mostly drunk all the time) learn that Sasha is up for the job, they get excited and Sasha ends up winning in a landslide.

Sasha then starts changing things around town. And helping the miner get better pay. Pike sits her down and says if she gets any chummier with the workers, he’s going to kill her. But she’s already in it. There’s no turning back now.

She enlists her new semi-boyfriend (Jack) for help, only to realize that he was secretly working for Pike this whole time! Jack swears he’s had a change of heart and wants to help Sasha. But can she trust him? Going off the many seasons of Love Island I’ve watched, I can tell you that when a man lies, he’s going to lie again! Stay away from him, girl! But who knows. Maybe Jack will surprise us.

What a weird script.

For starters, it does an excellent job making you love the main character. If you ever want to create a protagonist the audience loves, make your protagonist someone who’s being taken advantage of. And if you want the audience to love them even more, put them in a really crappy situation as well. Someone in a crappy situation who’s being taken advantage of is the screenwriting equivalent of saving thousands of cats.

You just feel for this poor woman. Her husband died. And this a-hole mine czar b.s.’s her about the insurance, saying her husband was negligent so she gets no money to raise her child. We hate this guy more than anything. And, of course, we’re rooting for our screwed-over protagonist to defeat him.

So that part of the script was great which, by the way, is the hardest part of the script to get right. Getting a reader to fall in love with and care about your protagonist is super difficult to do. You could write a thousand-page screenwriting book on how to achieve this and, still, 90% of screenwriters would struggle with it.

Pike is a great villain as well. You know who he reminded me of? Mr. Potter in It’s A Wonderful Life. But even nastier. Cause this guy is willing to kill you if you don’t do what he says.

If you’ve got a hero we love and a villain we hate, you’ve got a readable screenplay. Because when stories are told well, they’re an EMOTIONAL EXPERIENCE. The reader is FEELING SOMETHING. The more you’re making them feel, the more they’re going to like your script.

So the fact that we love Sasha and hate Pike does the heavy lifting for Pikesville.

Which is why it’s such a bummer that everything outside of the character work stinks like last night’s fettuccine alfredo. Nothing about this situation feels real. There’s zero specificity. I don’t know what state this is. I don’t even know what COUNTRY this is. Come to think of it, I don’t even know what YEAR it is.

I don’t know if the writer kept these secrets as a deliberate creative choice. But I don’t think he did. None of the character names were capitalized in this script when they were introduced. That tells me this is a newbie writer. And if they’re a newbie writer, they’re more inclined to make mistakes like being too general with the setting.

Why does this matter? Cause this movie plays different if it’s 1975 as opposed to 2023. Women’s rights weren’t nearly as advanced back then as they are today. Which would imply that the writer was making a commentary about that time. But it seems like it’s 2023 and yet we’re treating this girl like she lives in Russia 50 years ago. It’s hard to grasp what’s happening culturally.

This extended into the major plot beats of the script.

I consider major plot beats to be the pillars that hold your screenplay up. You need them to be strong. The first major plot beat here is the mayor saying to his cleaning lady, “You’re running against me for mayor.”

When has this ever happened in the history of the world?

That’s not a pillar made of stone. It’s a pillar made of styrofoam.

One last observation I had was that this is one of the slimmest scripts I’ve read all year. It’s so sparse. And that’s… a good thing? Right? We talk about it all the time. Make the script easy to ready. Keep your prose as sparse as possible.

That’s true for CERTAIN GENRES. But not for every genre. Some genres need more meat. You couldn’t write The Godfather, for example, with 2 line paragraphs all the way through. You wouldn’t be able to add the density necessary to give the story its required weight.

Same thing with Guardians of the Galaxy. There’s too much in that world that needs to be explained for them to distill it down to quick ‘soundbite’ paragraphs.

And I would argue it’s the same for Pikesville. It needed more description of the town, of the setting, of the people. It needed more detail in the interactions in order to convey the complexity of the relationships. Writing this in the style of a 90 minute thriller was not a good decision.

Main character was great. Villain was great. Any time those two were in a scene together, I was on the edge of my seat. But nothing else in the script worked, unfortunately. So I can’t endorse this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When major plot points arrive in your script, make sure they’re rock solid. The audience must believe in them 100% or else your story will fall apart. Who’s going to believe that a mayor forces his cleaning lady to run against him? I’m not even convinced you can get away with that in a comedy.

I love The Bear. It’s an extremely well-written show. So I thought, let’s bring “10 Screenwriting Tips” out of retirement so we can learn what screenwriting tricks The Bear is using to be so goooooood!

1) Obstacle Mania – Whatever your characters’ giant goal is, your job, especially in a TV show, is to place as many obstacles in front of that goal as you can. The Bear, Season 2, does this better than any show I’ve seen in recent memory. The goal is to open a new fancy restaurant. We’ve got IRS issues. Fire regulations. Finding an investor. Open in just three months. Mold. Walls falling down. Hiring competent staff. The list is never-ending. Obstacles create UNCERTAINTY IN THE NARRATIVE. Which is what you want. You want the reader to be unsure if the characters can do it.

2) Put your characters where they least want to be – Where you find the most drama in a story is when you place characters in places they do not want to be. Richie, the screw-up of the family, hates order and responsibility more than anyone in the world. This guy only thrives in chaos and disorder. In season 2, episode 7, Carmy gets Richie a job in the kitchen of the best restaurant in Chicago. Needless to say, the restaurant thrives specifically on order and responsibility. You can see Richie boiling over just standing in this place. It is the antithesis of him. Which is exactly why we can’t look away. This episode, “Forks,” is my favorite episode of Season 2 because of this lesson.

3) Intense conversations work better when at least one of the people in the conversation doesn’t want to be there – Intense dramatic conversations about life don’t usually play well. They often feel self-indulgent and fake cause kumbaya “I’m all up in my feelings” moments don’t happen all that often in real life. So a way to make them more palatable is to have at least one of the characters in the conversation not want to be there. In season 2, episode 1, an “up in his feelings” Richie is downstairs in the basement feeling bad for himself. Carmy comes down to grab something and Richie blurts out, “You ever think about purpose?” Carmy looks at him and says, “I love you but I don’t have time for this.” But then he sees Richie is really in the doldrums and decides to stay, reluctantly. Richie then makes his big, “I don’t feel any purpose” plea, and Carmy’s not really into it. He has a million things to do. But he stays and listens to the best of his ability. Carmy’s half-interest is what makes this scene work. Cause if they’re both really into this conversation, it’ll feel false.

4) Compounding outside pressure – One of the things The Bear does really well is it places pressure on its characters. But that’s par for the course. Every character should have pressure on them. What The Bear does, though, is it compounds that pressure. It adds ADDITIONAL PROBLEMS to the characters’ lives, which makes every scene feel even heavier, even more important. In “Forks,” midway through the episode, Richie calls his ex-wife, who he’s secretly hoping to get back together with, to manage a situation with their daughter. And the ex-wife tells him that she just accepted a guy’s proposal. This is what compounding pressure looks like. You never let your character off the hook. And the great thing about compounding pressure is that now, whenever Richie encounters an issue in the restaurant, we’re more afraid he’s going to crack. Cause we know that there’s additional things going on in his life.

5) The Scene Agitator – I would be surprised if creator Christopher Storer has not read Scriptshadow Secrets because this man LOVES the scene agitator. As a reminder, the scene agitator is any element you can add to a scene that agitates the characters in some way. Storer rarely lets two characters just talk to each other. He almost always has a third variable in play. For example, in season 2, episode 7, when Richie calls his cousin, Carmy, back at the restaurant, to ask him some questions, the team’s fix-it guy, Neil, is trying to fix a faulty outlet wire, which keeps electrocuting him. So Carmy is trying to talk to Richie while occasionally stopping the conversation to yell at Neil. “Neil! What are you doing! Get away from that thing.” Neil is the agitator here, and provides a more unpredictable conversation between Carmy and Richie.

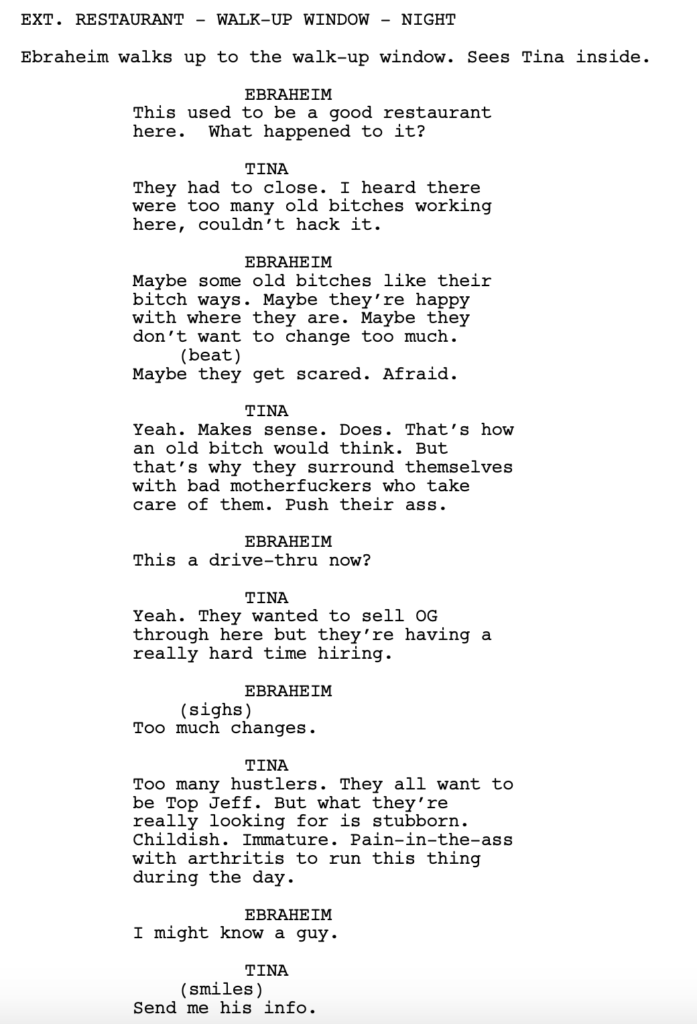

6) Pronouns and Role Play – This is a preview tip from my dialogue book. A great way to spice up dialogue is to have the characters in the scene playfully use the wrong pronouns as well as use role play, pretending they’re not the people they really are. It allows for a unique conversation that always feels more creative than the on-the-nose version most writers write. In season 2, episode 8, Ebraheim, an old-timer chef at the former restaurant who bailed when Carmy decided to upgrade the restaurant, comes back a couple of weeks before the new restaurant is opening. He runs into his old buddy, Tina, who still works there.

7) Nobody’s angry just because they’re angry. They’re angry because they’re scared – I read a lot of scripts where characters are angry because the writer wants an angry character. But they don’t think about WHY that character is angry. And WHY they’re angry is the whole ball of wax. Because most of the time, they’re angry because they’re scared. Cause they don’t think they can hack it. Like Richie. Richie is my favorite character in this show because of that inner conflict. He’s the loudest. He’s the harshest. He screams at people all the time. When he messes up, it’s always somebody else’s fault. And it’s all because he’s terrified. He’s terrified he’s going to be exposed for the scared little kid he actually is. So when a character is angry, give them a reason for being angry. I promise you, the character is going to come off as so much more genuine if you do.

8) Money makes the TV show go round – Money money money monaaaaay. MONNNAAAY. Money is a wonderful friend in any dramatically told story, but especially in television. The thing with TV is that it doesn’t have that ticking time bomb urgency that a movie can have since a movie is only 2 hours. With TV, the timespan is always longer and so we lose out on that urgency. You can compensate for this by adding a money issue. Your main character(s) should be under some sort of monetary deadline. With The Bear, in order to get the investment for the restaurant, Carmy has to agree that if his uncle isn’t paid back in full within 18 months, the uncle gets the building. Never having enough money is such a universal experience that we always relate to money problems in stories.

9) Make sure to balance the sour with the sweet – The Bear puts its characters through the wringer. It really whacks them up against the head with a lot of crap. If all you do, though, is hurt your characters, your reader will grow frustrated. We’re not sadists. We need good amongst your bad. And The Bear is good at this. It makes sure to intersperse the bad with a nice little occasional scene that gives you the warm and fuzzies inside. In the first episode of season 2, there’s a scene near the end of a tough episode where Sydney, the smart-as-a-whip prodigy sous-chef, runs after Tina, the old school “been here forever” cook who’s accepted her lackluster lot in life. Sydney asks Tina if she would be her assistant. And we just see Tina’s eyes light up when she realizes what Sydney is asking. It’s such a sweet moment as well as a NEEDED ONE. Because we need the sweet within the sour.

10) Scenes With a Lot of Characters In Them – The Bear has a ton of scenes with a lot of characters in them. For these scenes to work, you need to know who your CONTROLLING CHARACTER in the scene is. Your controlling character is the character who wants the most out of the scene. They have the big objective that’s driving the core of the conversation. So in Season 2, Episode 5, five minutes in, Uncle Jimmy (the investor) shows up to the restaurant to check on things. He walks into a room with, literally, seven other characters and everyone in the scene talks at some point. But the scene keeps coming back to Uncle Jimmy because he’s the controlling character. He is the one who wants the most out of this scene. He wants to know that they’re going to be ready to freaking open when they said they’re going to be ready. So that’s what drives most of the conversation, is his questions and directives regarding that topic.

100 dollars off a Screenplay Consultation (feature or pilot) if you e-mail me with the subject line, “THE BEAR!” carsonreeves1@gmail.com. What are you waiting for??