Search Results for: F word

Genre: Dystopian/Horror

Premise: Twin sisters live in a commune where, once they hit puberty, one of the twins becomes a monster and must be killed. But when the twins learn that their community is keeping big secrets from them, they make a run for it.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List with 9 votes. Alexander has written a couple of short films that he’s directed.

Writer: Alexander Thompson

Details: 117 pages

Jenna Ortega playing twins?

Jenna Ortega playing twins?

Reading scripts that don’t fall under your genre preferences is always a difficult thing. But you have to do it. You have to step out of your comfort zone. Because you never know when you’re going to read that really unique screenplay that blows you away.

With that said, these dystopian commune/lab stories have always felt like a house of cards to me. They never have a lot of meat to them. From Spiderhead to The Giver to Divergent to Equals to The Maze Runner. They give you that one rule that makes their story different from all the others. But the rule is so basic that it doesn’t have the strength to hold up an entire movie.

The only one that worked was The Hunger Games and that’s because it leaned more into its high concept than its dystopian commune genre roots. A movie about kids who have to kill each other, the ultimate irony, is a slam dunk. But all the rest of these might as well be constructed with balsa wood.

I hope to be proven wrong.

Aurora and Gabrielle are 16 year old twins. Which is unusual in our odd dystopian setting. They live in a giant commune in the countryside full of twins. And when the twins go through puberty on this commune, one turns into a rabid monster and the other doesn’t. The town then quickly kills the dangerous monster and the surviving twin moves on with their life.

Aurora, the good girl, and Gabrielle, the bad one, are way past due. Which makes them the focus of everyone’s untrusting eyes wherever they go. One day, when a guy friend of theirs turns, Gabrielle and Aurora find his new monster-self hiding, and realize that he’s totally coherent. He’s not some violent crazy monster like they’ve been educated to believe.

With this shocking new information, Aurora and Gabrielle go on the run, heading into the countryside and staying at a motel. But when they’re recognized, the cops come and grab them, but don’t take them back home. It turns out these monster things are worth a pretty penny on the open market. So Aurora and Gabby escape THEM and that’s when they meet Marty.

Marty is a kind woman who lives in the middle of nowhere. She knows who they are and doesn’t care. She feeds them and tells them they can stay here was long as they want. But one day Aurora follows Marty into the forest to find that she’s locked up a monster in a barn. Not just any monster – Marty’s twin. Yes, Marty once belonged to the commune as well.

It appears that Marty is either going to feed these two to her monster brother or have them mate or who knows what else. Aurora and Gabrielle will have to make one last escape, an escape that will be aided by one of them finally turning.

Ooh boy.

Okay.

This is a typical 2020s Black List script.

It’s got some good stuff in it. But there are just as many times when it feels like it’s being written by a beginner.

The overwriting in particular. Goodness me!

I’ve read so many scripts at this point that I know, when I see the genre, EXACTLY what the page length needs to be for that script to be in its genre sweet spot. If the page count is either shorter than that or longer than that, I know the script won’t be good. This is a 105-110 page concept.

The problem is that it’s overwritten. Every paragraph could be cut in half. For example this: “AURORA has followed her. Gabrielle shakes her head, ‘You needn’t come along’… But Aurora ambles quietly to her side, and onward they go together.” Could easily be: “AURORA follows along. Gabrielle shakes her head, ‘No.’ But Aurora insists and they continue on.’”

You may look at that and think I’m nitpicking. Trust me. When there are 1000 paragraphs in a script that all read too bulky? That drives the reader insane. More importantly, it slows your script waaaaaay down. Which was a huge problem here. I thought I was on on page 45. I checked and I was still on page 24. That issue was specifically due to this overwriting.

And by the way – yes, it’s better to break your action-description paragraphs up into 3-line chunks as opposed to writing 10-line paragraphs. But if you’re writing an entire page of 3-line paragraphs with no dialogue, it’s not that different from a reader having to read 2 15-line paragraphs. It’s still a wall of text.

So the solution is to cut down the overall words that you’re writing. Cause chances are you’re using a lot more words and sentences than you need to. ESPECIALLY if you’re a beginner. Beginners always make this mistake. And it’s a huge reason why they don’t get responses after script reads. It probably doesn’t have to do with the story content as much as the reader getting frustrated by the endless of chunks of needless sentences they have to endure.

This script suffered big time from that.

Now, like I said, it wasn’t all bad.

The story is built around a strong line of suspense. We know that one of these girls is going to turn into a monster at some point. That’s a nice dangling carrot to keep us turning these overwritten pages.

There’s contrast between the two main characters, the sisters. Gabby’s a shark. Aurora’s sweet. What this does is that every time the two encounter an obstacle, they’re going to have different opinions on how to solve the problem. That’s where you get your conflict. And if you add some urgency to those situations – such as there’s a cop coming downstairs in five seconds and a decision needs to be made – you’re going to come upon some entertaining moments.

Also, once they leave the commune, the script becomes a million times better. Getting through that sludge-like opening act was like trying to run during a nightmare. You’re not going anywhere. I think at one point I had turned the page only to find out I’d somehow gone backwards.

Why is that? Well, because the first act was built entirely around WAITING AROUND. I’ve told you guys this before. “Waiting Around Narratives,” are some of the most boring narratives you can write. Movies work best with active characters, not passive characters. Once these two become active and go on the run, the script gets a shot of adrenaline.

It wasn’t enough to win me over, though. The YA lab genre has always been uninspiring to me. I feel like anyone could come up with one of these concepts in thirty seconds. Here, I’ll come up with one right now. Children are all raised in a remote commune. At 10, all girls become vampires and all guys get telepathy. Boom, there’s a YA concept for anyone who wants it.

I’m joking but they really do come off like that sometimes.

I will give this script credit for making me care more than I usually do for this genre. But the overwriting and the fact that it’s not my thing makes this a ‘no thank you’ on my end.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t listen to me when it comes to the commercial viability of YA concepts. I may not like them but a lot of people do. So if you like YA, write a YA script. I would extrapolate that advice beyond YA. Don’t make decisions about what you do or do not write based on one person hating that type of movie. In the end, if you’re passionate about the concept and think you’ve got a great idea where you can bring something fresh to the script? Then go ahead and write that script.

What I learned 2: Also, for all my bickering about this subject matter, I give credit to the writer for writing a coming-of-age movie with a marketable slant. This is way more interesting than if it had been yet another script about a girl coming of age in her boring small town.

Genre: TV – 1 hour drama

Premise: Two dads in Suffolk County engage in an intense feud that bubbles over into their innocent childrens’ baseball league.

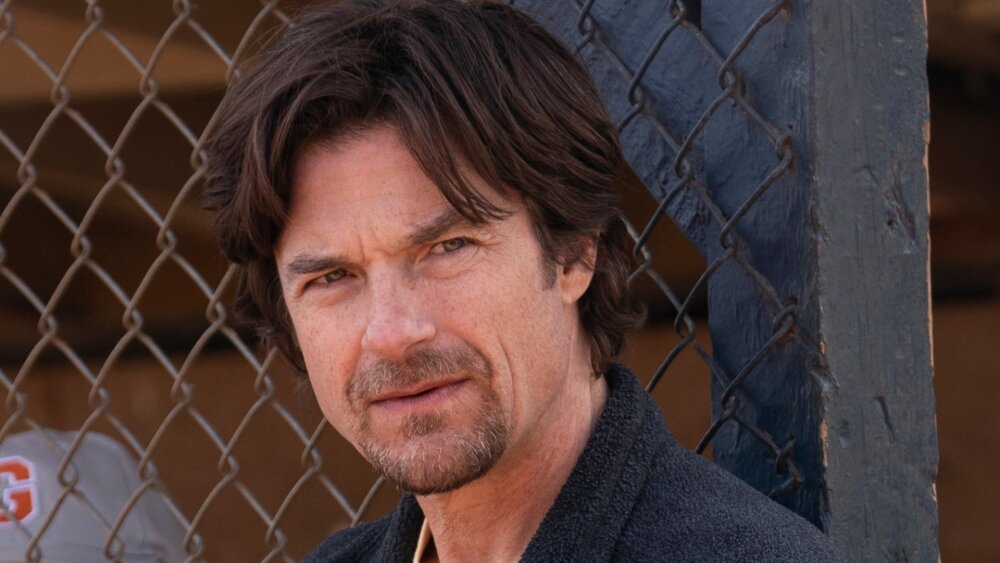

About: A huge article purchase from over on Esquire (article has a paywall unfortunately). Jason Bateman and Netflix continue their love affair as the streamer paid big bucks to bring their Ozark pal back into its arms (Netflix beat out SEVEN other rabid suitors). Bateman will direct and star in the show about two little league fathers who get into a very intense rivalry that involves criminal activity. They’re going to have to figure out a better title though because when I first saw this, I thought it was a story about a Cinderella-type ball that dads attended.

Writer: David Gauvey Herbert

Details: About 6000 words

One of the best ways to sell anything in this business is to write a story that’s similar to a recent hit.

This actually used to be harder because the strategy was built almost entirely around giant movie successes. So if Armageddon made a billion dollars its opening weekend, you’d be competing against thousands of other screenwriters with your “Armageddon adjacent” spec script. A giant Astroid threatens the world? Well, what about a giant tidal wave!?

But these days, there are a lot more opportunities because success has become more relative and diversified. A crafty screenwriter looks for smaller “mini-successes” and pitches projects similar to them.

Case in point, today’s sale. The Daddy Ball project was clearly pitching itself as “The next Beef.” And boy is that a powerful pitch when all of the elements align. You have to be in the minds of these buyers. They’re terrified of buying something that sucks. So any little image you can put in their mind that indicates success – like a recently popular show – helps out.

With that said, I’ve found that you have to be careful not to jump onto mega hits. I experienced this myself a couple years ago while trying to pitch a really good racing pilot with a writer. We pitched it as a Succession set in the south. What I didn’t realize was that, literally, EVERYONE was pitching “Succession set in the [blank].” And when that happens, the pitch goes right through one ear and out the other.

This pitch was perfect because Beef was a hit but a low-key hit. Not everyone saw it. And not everyone who did see it, liked it. However, the people who did like it, loved it. And, so, when you pitched “Beef set in the world of little league baseball,” your competition was small and the people who loved Beef were DEFINITELY going to request the script.

Back in the late 2000s, in Suffolk County, Bobby Sanfilippo was excited to get his 10 year old son into the local little league scene, which was becoming a big deal. To get on one of these traveling teams, you had to fork up a couple grand. But Bobby was more than happy to, since his son (who can’t be named) loved baseball.

Bobby’s son joined a team called the Inferno and that’s when Bobby first met John Reardon, a sort of daddy psychopath. John’s son Jack would come onto the team and be an instant star. He had all the makings of a kid who could go pro one day. Much better than Bobby’s son, who was just a good player who loved baseball.

When the team started to get really good, parents wanted to get rid of the weak players. John seemed to spearhead the movement to get rid of people like Bobby’s son. So Bobby, who was doing well financially, took his son and STARTED HIS OWN TEAM, naming it, “Vengeance.”

Not long after, the two teams would play, Jack’s team would win, and John would scream some really terrible things at Bobby’s son. When the Vengeance coaches called him out on it, John pulled out a bat and came at them. In the end, everybody calmed down, but this daddy rivalry had gone up a notch.

One day John started getting all these text messages sent from an anonymous phone that contained pictures of his family doing everyday activities accompanied with threats that John was “done.”

Several months later, during a Vengeance game, the police showed up, arrested Bobby for the messages, and made him do the perp walk of shame in front of his team. Although Bobby denied sending the messages, the damage had been done. The team was never the same since many of the parents believed Bobby was guilty.

Bobby had always contended that John was friends with the local police chief and the two had constructed this hit job together. A couple years later, this gained more credence when that police chief was taken down by the FBI for running his precinct like the KGB. In the end, both fathers still think they were right in all the things they did. And both still hate each other.

I’m not sure what to make of these non-traditional magazine article sales. You guys remember that Monopoly one from a couple of years ago? The one that Matt and Ben bought? That thing died in a blaze of glory quicker than you could say, “How bout them apples.”

I understand why this sold. In addition to the “Beef” connection, you’ve got that all important conceptual irony to hang your baseball cap on. It’s because this is set in the world of little league baseball that it has a juicier taste. You shouldn’t be sending life-threatening messages over junior sporting events.

But I was hoping for a lot more chaos. I actually thought, when I read about this in the trades, that it was going to end in murder. That’s the expectation with these true stories now. So, when you don’t get all the way there, the audience is like, “That’s it??”

At the very least, I was hoping for an ongoing rivalry between the two teams. But there were only two games and both of them were uneventful except for Jack striking out Bobby’s son and John bringing out a bat afterwards, a bat he didn’t even use.

That’s what this story felt like to me. A whole lot of blue baseballs. It was always on the brink of something gnarly happening but nothing gnarly ever happened. In fact, any sort of issue between the two dads was an adjacent issue. When Bobby’s son left the Inferno, for example, it wasn’t John who kicked him off. It’s not even clear if John had any opinion on getting Bobby’s son off the team.

And then there’s this big thread about how John was distantly related to the local police chief, which is why the two had worked together to illegally take down Bobby. But that’s never proven. The evidence actually leans towards the two never having spoken to each other in their lives.

Stories work best when the attacks ARE DIRECT. Not adjacent. In Beef, it wasn’t that Danny *might have* kidnapped Amy’s daughter. He *DID* kidnap her daughter.

Unfortunately, this feels like a writer who thought there was more to this story than there was, spent a couple of years and a lot of interviews on it only to find out, in the end, it was really a rather tame story. He then did his best to imply a lot of bad things happened.

To be fair, it worked out. It’s being turned into a TV series. But for this to work, they’re going to have to add A LOT MORE to the story. This needs to be completely fictional if it’s going to be as entertaining as Beef. If they filmed this as is, people are going to leave this series saying, “Did you really just make a TV show about two people who yelled at each other a couple of times?”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In a script like this, you need at last one “Holy S—t” moment. If you don’t have a “Holy S—t” moment in a movie or show about a bitter feud, then the feud you’re writing about isn’t nasty enough. Beef has that shocking traumatic ending. There’s also the house burning down. There’s Danny secretly sabotaging his brother’s future. There isn’t a single “Holy S—t” moment in Daddy Ball.

A reminder that the June Logline Showdown deadline is THIS THURSDAY! Scroll down for details on how to enter!

Genre: Action/Comedy

Premise: A stunt man on location in Italy is mistaken for a famous assassin who just tried to take out one of the country’s biggest businessman. The businessman puts his entire financial weight behind finding and killing the “assassin.”

About: This script finished in the middle of the pack in last year’s Black List. The writer, Will Lowell, received his masters degree in film and television from USC. Up to this point, he has written and directed several short films.

Writer: Will Lowell

Details: 111 pages

A reminder that THIS THURSDAY is the deadline for LOGLINE SHOWDOWN. So get those loglines in!

When: June 23rd

Deadline: June 22nd, 10pm Pacific Time

Where: e-mail all submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

What: include title, genre, and logline

On to the review!

If you’re a writer hoping to become the next Christina Hodson, Joby Harold, or Michael Waldron, screenwriters being hired to tackle these behemoth franchises, the genre you want to choose for your next script is Action-Comedy.

Those are the two most important ingredients for these mega-franchise movies. They want you to be able to come up with awesome set pieces (like babies falling from a building) and they want you to be funny. Studios need audiences coming out of their movies feeling like they had a good time. And the number one way to accomplish that is to make people laugh.

Some say the spec sale is dead. That’s incorrect. It’s just delayed. You write a great action-comedy spec and don’t get paid for it. But if someone hires you to write Iron Man 4 because they loved your spec, you, essentially, just sold the script that got you the assignment.

But what this means – if you want to make a lot of money as a screenwriter – is that you have to be strategic about the genre. You have to choose a genre where the biggest potential extrapolation of that route equals the biggest payday. Action-Comedy is the big enchilada in the payday department.

Sam Clark is one tough stunt man. The guy did several tours in the military. Now he gets to travel to unique places all over the world and do stunts for movie stars. He’s currently in Italy doing stunt work for an annoying Channing Tatum. During a particularly difficult stunt, he badly cuts his hand.

Elsewhere in Italy, a notorious masked assassin named Il Pistone attempts to assassinate a business magnate named Giuseppe Greco in his mansion, but unintentionally kills his adult son. Pistone aborts the mission but when he’s escaping, he cuts his hand on the fence. Giuseppe then puts the word out to every criminal in Italy to kill Il Pistone!

After a tough day on set, Sam goes to get a drink at a bar and meets a hot young lady named Clara and the two sleep together. The next morning, while Sam heads to set, he’s attacked by a random man. Sam’s military training allows him to escape. But soon, he realizes this is just the start. More and more men come out of the woodwork to try and kill him.

It becomes clear that Sam, because of the whole injured hand thing, has become mistaken for Il Pistone. And even going to the U.S. Embassy doesn’t help. Greco has too much influence here and so even Sam’s Murica brothers are after him.

While running around the city, Sam bumps into Clara again, who’s pissed off that she hasn’t received a text after their tender lovemaking session the night before. (Spoiler) But it turns out Clara isn’t being totally honest with Sam. That’s because Clara is Il Pistone! Eventually, Sam figures this out, and the two decide to team up to take down Giuseppe Greco.

This script was good.

But I’m still frustrated by it.

How can that be, you’re wondering. A good script is a good script. What else is there to discuss?

Here’s the problem. Good scripts are great. But great scripts are better.

The thing about good scripts is that there are a lot of them. Therefore, when you write one, you’ve only succeeded in getting lost in a sea of good scripts. You haven’t separated yourself.

Take the opening scene here. It’s as assassination scene.

It’s well written. It’s paced well. It’s described well. There’s a little bit of suspense. It has an emotional moment between father and son.

But I have read, literally, one thousand scenes just like it.

That’s the problem with a good script is that a good script is code for “good enough.” But “good enough” doesn’t get you much. It gets you acclaim from bored Black List voters who are used to reading lots of bad screenplays. They’re just happy that, for once, they’re not clawing their eyes out.

But this business is so freaking competitive that “good enough” is almost as bad as bad. Some might even argue bad is better. Because readers remember bad scripts. I remember Orbital. But good enough scripts? I’ve usually forgotten those by Sunday.

Someone just e-mailed me the other day for a script I reviewed a couple years ago. I had no idea what he was talking about. He kept telling me that I liked it. I gave it a “worth the read.” I finally found the script and, like this one, it was good enough. Good enough to get that ‘worth the read.’ But not good enough to be memorable.

I don’t know if there’s an existential plane for screenwriting discussion. But if there is, I would ask, after every script, “Does this script have a soul?” Or is it just a screenwriter executing a concept according to the steps he’s been told to take?

I watched this Black Mirror episode last night called Beyond The Sea. It’s complicated to explain but, basically, two astronauts on a deep space mission can link up with perfect human avatars of themselves back on earth so they don’t go insane in their tiny ship with nothing to do for years at a time.

One of the astronauts starts inhabiting his partner’s body back on earth and falls in love with his partner’s wife in the process.

That script had soul. It explored the human condition in a complex and, yet, universal way. It displayed tragedy, sadness, falling in love, happiness, jealousy — all these universal human experiences that, when added up, gave the script a soul. And, to be honest, I didn’t really like the episode. It was too dark and sad for my taste. But did it have soul? You bet it did.

Now, you may say: “Action/Comedy, Carson. None of those movies have souls. They’re dumb escapist fun.” Wrong. I just watched an action comedy yesterday that had a soul. The Flash.

It’s frustrating because I can go into a lot of the things that this script did well, particularly its plotting. The reveals (Clara is Il Pitone) and double-crosses (the Embassy is going to kill Sam) and the dramatic irony present late in the script when Sam thinks he’s protecting Clara when it’s really her protecting him.

Or when when Sam realizes that the only way out of this is to find and kill Il Pitone, and Clara is trying to talk him out of it because, of course, she’s Il Pitone.

All that stuff was fun.

But then you get this really over-leveraged Channing Tatum joke. If there’s anything that’s going to steal the soul of your script, it’s a drawn out Channing Tatum joke. Channing Tatum plays himself for a joke in EVERY MOVIE! That’s all he does these days. Which makes it a soulless creative choice. Go with someone unexpected. Josh Gadd in his first action film. Or weirdo Joaquin Phoenix. When you go below the surface with your creative choices, it’s like massaging your script with soul moisturizer.

This is more important than ever in the era of AI. Because AI is about to start spitting out really generic screenplays. Therefore, if you’re not consistently making interesting/risky/unique creative choices, your scripts are going to start getting mistaken for AI scripts.

Don’t get me wrong. Match Cut is not AI bad. But it is by-the-book. The writer masked a lot of that because his execution is strong. But it still feels like a script I’ve read many times before.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As you know, I always appreciate a good character description. Here’s one I really liked in Match Cut: “AGENT GRANT (60s, ill-fitting suit, a Cold War relic lost in a sea of data analysis and predictive algorithms).” The writer uses something I call “essence description.” This is when you describe someone in a way that allows us to understand the essence of who they are.

James Gunn helped me remember one of the most powerful components of a great story

I was watching James Gunn do an interview with actor and podcaster, Michael Rosenbaum. For reference, they’re good friends. And, also, Rosenbaum played Lex Luthor in the show, Smallville.

One of the topics that came up in the podcast was “superhero fatigue,” which Gunn admitted was a huge problem for moviegoing in the current era. But he went even further than that. He said he’d grown fatigued by all spectacle movies.

One thing he said really stuck with me. He said he couldn’t remember the last time he watched the third act of one of these spectacle movies AND ACTUALLY CARED ABOUT WHAT WAS GOING ON.

This is the same reason why I’ve been so reluctant to see Hollywood movies lately. It’s why I didn’t see Ant-Man. It’s why I didn’t see Fast X. It’s actually why I didn’t see Guardians (as I assumed it would be yet another third act Marvel mess).

But it was what Gunn said next that really hit hard. He said, “You don’t feel anything for the characters. And if you don’t feel anything for the characters, you don’t care what’s going on.”

This immediately got me thinking about how to get the audience to care. What makes me care about a story? Luckily, I just read a great story yesterday, in “Wild,” about a werewolf who takes in a thief on the run. What was it about that script that made me care?

Simple, really.

The central relationship.

We put so much focus on the hero in screenwriting that we’ve lost sight of the fact that what really makes us care is our main story pairing. Because just like in real life, there’s power in numbers. Why rest everything on a lone hero’s accomplishment when you can pair two people up and have them experience that victory together?

There is something about watching two people connect and overcome obstacles that hits the audience harder than when just one person does it. Would it have been cool, yesterday, to see just Liz beat up all the bad guys with her werewolf powers? Sure. Would it have been cool to see just Nick kill all the shady gangsters who chased him into town? Sure.

But watching them both do it TOGETHER? Watching them depend on each other? That feeling of accomplishment is multiplied because we’re not just happy for him or happy for her. We’re happy because each of them helped SOMEONE ELSE. It was not a selfish act. It was a selfless connective act. And that’s what gets audiences feeling all warm and fuzzy inside.

I relate this to playing tennis. I kinda hated singles growing up. I felt good when I won, I guess. But I was never happy when I was playing the match. I was always screaming at myself and upset that some part of my game wasn’t working. When I won, I was just happy that I didn’t lose. I felt like Jokic after winning the NBA finals. Just let me go home.

But I LOVED doubles. The specific reason I loved doubles was because when I won, I got to share that victory with someone else. Usually, a good friend. There was nothing better than that feeling.

What James Gunn is talking about is the erosion of the screenwriter’s focus on this tool. The reason we don’t care about the ending is not because of all the cheesy VFX – although that’s certainly part of it. The reason we don’t care is because we don’t care about these characters and we certainly don’t care about their connection with one another.

None of this is to say these companies aren’t trying.

No producer is going out there and saying, “Who cares what the audience thinks of our characters.” Quite the opposite. If you listen to Kathleen Kennedy, she can’t stop talking about the importance of characters.

So then why do all her characters suck?

It’s because they’ve forgotten that it isn’t just about making your hero likable. It’s about the Power of Two. You have to make the hero likable and then you have to develop a compelling relationship with another character who we care about and now your story is turbocharged. Cause we’re not just rooting for the hero. We’re not just rooting for the co-hero. We’re rooting for them as a team.

“Okay,” you’re saying. “But how do you develop a Power of Two who we actually care about, Carson? Cause just saying ‘create two characters instead of one’ doesn’t automatically result in a great script.”

True dat.

We can look to yesterday to get our answer to this. There’s one primary ingredient you absolutely must inject. And that’s CONFLICT. You have to create conflict within that primary relationship.

What that conflict does is it PUSHES your central characters apart. And then, in order for them to be victorious, they must PULL together. If you get that push-pull right? That’s your golden ticket to screenplay nirvana. If you do nothing else right but that, you’ll have a good screenplay. That’s the secret sauce.

So, yesterday, what’s PUSHING them apart is that Liz is a werewolf. But they can’t defeat the sheriff’s family or the criminals unless they PULL together.

But don’t take some unproven Black List script’s word for it. Look at two of the most successful movies of all time – Titanic and Avatar. Jack and Rose are pushed apart by society. But they must pull together to survive the sinking of the ship. Jake and Neytiri are pushed apart by being from two different cultures but must pull together to defeat the human’s military attack.

That’ll do the majority of the work for you.

But if you want to really make people care, follow this one-two punch: Make the central relationship interesting in some way. And make it specific to your movie.

You can’t just have two people be friends and we’ll magically care about their relationship more than anything in the world. Use the conflict to create an interesting pairing.

That’s what I liked about Wild so much. It was such an interesting dynamic. He was on the run and needed a place to stay. He doesn’t like this woman but he’s got no other choice so he stays in her barn. She’s a werewolf. She could potentially kill him. Talk about a messed up way to start a relationship. This interesting pairing that has conflict up the wazoo and was specific to the movie made for two people we instantly cared about.

Contrast that with Jason Reitman’s Labor Day where the female lead pretty much likes the criminal right away. He likes her right away. They’re reenacting the pottery scene from “Ghost” within five minutes of getting to her house. It’s just boring. Without that genuine conflict and interesting connection, we’re bored by them. And if a relationship starts off boring, it’s almost impossible to salvage it.

I’m reminded of one of my favorite movies growing up, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, which is the perfect example of this formula’s power.

You have selfish Ferris, who just wants to have the best ditch-day ever. And then you have Cameron, who’s sick as a dog and just wants to be left alone. That’s the conflict that’s pushing them apart.

I can’t emphasize this enough. John Hughes could’ve easily made Ferris and Cameron the best of pals, party animals who were both on the same page about ditching school that day. Many lesser writers would’ve written that exact setup. By Hughes creating that conflict, he makes their relationship instantly more compelling.

And if they’re going to have the best day ever, they’re going to have to pull together despite that. That push-pull is the movie-within-the-movie that makes Ferris Bueller’s Day Off so iconic.

That scene at the end? The one where they’re sitting in Cameron’s dad’s car trying to run back the odometer? The level of emotion in that scene? That’s what Gunn is talking about when he says we don’t see that anymore. Because writers and studios aren’t doing the character work required between the two leads to make moments like THAT happen.

If they made that movie now, that scene would just be words. We wouldn’t feel a thing.

So, on your next script, make us care about your hero, yes. But, also, make sure the central relationship with that other main character is in place. Because we will care more about two people succeeding together than one person succeeding alone. Always.

Get a Script Consultation With Carson for $150 OFF! – In addition to logline consultations (just $25!), I do full screenplay consultations, pilot script consultations, outline consultations, first act consultations. Anything you need help with, I can help! If you mention this article anytime this week, I will give you 150 dollars off a feature (or 100 off a pilot) consultation. :). E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com

(TOP 25!!!) – One of the cooler crossovers I’ve read in a long time. A History of Violence meets An American Werewolf in London meets Let The Right One In.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A werewolf living on a remote farm with her older sister takes in a thief on the run just 72 hours before the next full moon.

About: This script finished on the Black List. The above logline you read was my logline. But since I’ll reference it in the review, here’s the very un-horror sounding logline from the Black List: “A young woman is determined to protect a thief on the run when he holes up in her small town, even if it means revealing a darker, more violent secret of her own.”

Writer: Michael Burgner

Details: 110 pages

It can be VERY difficult choosing a script to review from the Black List. Make the wrong choice and you could find yourself sifting through 120 pages of high school freshman level writing. Make the right choice, and you may find yourself the next Nightcrawler.

The stakes are high.

For this one, I noticed that Sugar23 represented it. I know they represent creators who did True Detective and 13 Reasons Why. I also noticed that even though the Black List logline made the script sound like a drama, that the writer had a couple of short films to his name that were horror. So I figured… hmmmm, maybe that means this one is a horror film too.

That was enough to seal the deal. And boy did that research pay off!

We meet Liz, who lives in a Kansas farmhouse with her sister, Jean. Liz has ugly scar tissue all around her neck. What’s that about? She walks downstairs where Jean is waiting. The two walk outside, across the yard, to the storm cellar. They go inside. There’s a big rusty chain and collar attached to a concrete wall. Jean and Liz place it over Liz’s neck, lock it, and Jean heads back into the house.

Later that night, a semi-truck screeches to a halt on the nearby highway. Jean sees this. Oh no. Jean runs across the field to the truck, hollering at the driver to get back in his truck. The driver, who thinks he hit something, gets WHACKED by a blur, pulled into the nearby corn field. Jean turns around and sprints with everything she’s got back to her house. It doesn’t take long for us to figure out what happened. Liz is a werewolf and got free from her restraints.

Cut to a medium-sized town several weeks later where Nick and Crispy barge into a strip club to rob it at the end of the night. After Crispy goes rogue and gets shot, Nick is able to get away with the money. But the owner’s security, a Navajo psychopath named Hashke, along with the owner himself, are already planning on how to retrieve his dough and torture this man.

During the getaway on his motorcycle, Nick’s battery was shot. So when the motorcycle dies, he’s forced to hitchhike. This is where he meets Liz, who looks like she’s going to pick him up, but instead tells him to get cleaned up and drives off.

Furious, he walks the rest of the way to town, where he runs into Liz again, ignores her, and heads to the hardware store to get a battery for his bike. The owner says it’s a special delivery and will take 72 hours. When Liz sees Nick throwing around money, she offers him a place to stay at her barn. Realizing that people will talk if he stays in town, he decides to take her up on her offer.

Meanwhile, Ruby, a sheriff, has made her way into town to find out exactly what happened to her husband (the trucker), and Hashke, taking a page out of Anton Chigurh’s book, has arrived in town in search of Nick. Oh yeah, and did I mention there’s a full moon in three days? About the same amount of time that Nick plans to stay at Liz’s? Yeah, I’m starting to think we’re going to get one hell of a climax.

When people talk about the difference between amateur and pro writing, it often sounds arbitrary. A lot of times it just means the reader likes this script better than that one.

So let’s get specific. Cause this script is a a great example of what a truly good screenwriter looks like when they’re putting together a story. I can show you specific examples of what the difference between advanced and intermmediate looks like. So let’s get into it.

For starters, there’s the robbery that opens Nick’s storyline. Nick is robbing a strip joint with Crispy. They get in there, it’s a room full of people, and when the initial threat of a stick-up doesn’t receive the proper fearful response, Crispy slides open his jacket to reveal that he’s strapped with explosives.

Nick stares over at this the same way everyone else does, with a giant “WTF” look on his face. This was the first indication that we’re dealing with an advanced writer. 99% of writers are going to have their robbers in lockstep, cause they’ll think of them as one entity.

But it’s so much more interesting to the story if one of these two go rouge. It instantly turns a black and white situation gray. And that’s where all the fun is.

Cut to a few scenes later. Nick’s motorcycle breaks down and he’s hitching on the side of the road. Liz is driving down that same road, sees him, and stops. Keep in mind, Nick still has blood on his face from the botched robbery.

Now, let me explain to you how an amateur writer thinks in this moment. They know that Nick is going to stay at Liz’s place. They know that’s the next major plot point. So they view things through the eyes of getting to that plot point ASAP. Therefore, they have Liz see this bloody man hitchhiking, pick him up, and take him to her home.

But in what reality would that happen? What woman is going to pick a bloodied hitchhiker up. That’s how the advanced writer looks at it. They look at it more from a perspective of reality. Of course you’re not going to pick him up. So after a few words with the man, Liz tells him that if he expects anyone to pick him up, he’s going to have to get cleaned up first. Then she drives off.

But here’s where the writing goes from advanced to very advanced: That scene does double duty. Not only is it more truthful but it establishes REAL CONFLICT between the two. Nick hates this girl now. The beginner screenwriter just has his two leads hate each other because it works better for what he’s trying to do. Who needs a *reason* for that? Here, the writer actually creates a reason for Nick to dislike Liz, establishing the necessary conflict between the two leads.

Later, the two re-meet at the hardware store. Liz sees Nick throwing money around. Liz’s farm is going under. Money is everything to her right now. So she offers him a place to stay while he waits for his battery to come in (another well-done, underrated, part of the plotting – the time constraint) and when she brings him back to her place, Ruby is sitting there, the wife of the dead trucker.

This is an EXTREMELY strong writing choice and let me tell you why.

Nine of out ten writers would’ve taken a break at this moment in the story. We just went through Liz meeting Nick on the road, Nick buying the new battery, the two negotiating him staying over… it would’ve been easy to take a couple of scenes off with Liz just sort of sitting in her room and looking tired. Or showing a “day in the life” of living on the farm. I know a lot of writers who would’ve done that. Five pages of mush before we get back to the plot.

By having this obstacle waiting for her – the wife of the man she killed sitting on the couch – tells me that this writer gets it. He knows that movies in small towns on farms die a lot quicker on the page than the Mission Impossibles and the Jurassic World’s of the world. So he knows that he has to keep things moving. It was moments like this that elevated this script above 99% of the other scripts out there.

And then, like any good horror film, you have this looming danger that’s coming. We know that the full moon is 3 days away. We know that Nick is the perfect food source. Nobody will miss him if he disappears. So we’re wondering, is he dead meat? Or is she going to start liking him enough that that doesn’t happen? Or maybe still happens?

And then, as if all that isn’t enough, you have not one, but TWO looming obstacles imposing on the central storyline. One is Ruby, a cop who wants to know what happened to her husband. And two is Hashke (and ultimately the strip joint owner), who want to kill Nick and get his money back.

I honestly don’t know if you could’ve come up with a better series of creative choices than was made here.

All of this sitting on top of the best creative choice of all, which was to make this a horror film. Too many writers would’ve written the version of this that the Black List logline implies. Which is a criminal who stays with a woman while avoiding the bad guys chasing him. That story ISN’T SEXY ENOUGH for a screenplay. You need a genre element to make people care (not to mention, make it marketable!). And that’s what we get here. We get the werewolf element.

How do we know that the non-genre version doesn’t work? Cause we’ve seen it. Jason Reitman’s snore-fest, Labor Day. Same premise. But no werewolf. Which equaled 1000x more boring.

This is the kind of script that, if you can internalize all the choices made here, starting from the concept then moving into the plotting itself, you will massively improve your own screenwriting. Every screenwriter should read this script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive (Top 25!)

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “Meet Mean.” We’ve all heard of the “Meet Cute.” But how much more interesting is it when your male and female leads are introduced via a “Meet Mean,” as was the case here? Liz drives up to Nick, asks him a few questions, lets him know there’s no way she’s letting him in her car, then drives off. I find that WAY MORE interesting than if they had an instant obsessive infatuation with one another.