Search Results for: F word

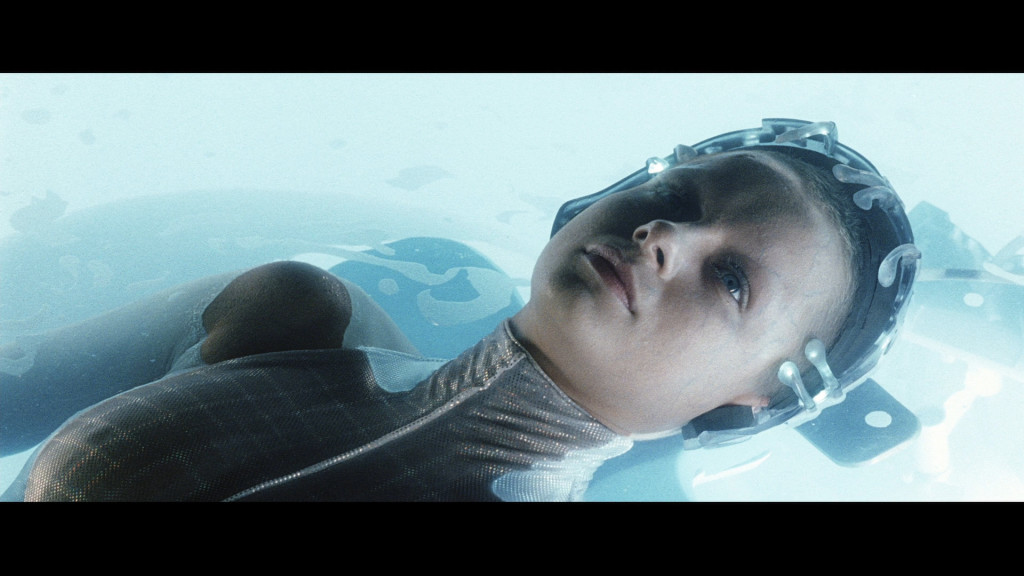

Genre: TV Pilot – Sci-fi

Premise: In the future, after the elimination of the faulty “pre-crime” program, a veteran cop and a former member of the program team up to solve a murder… that hasn’t happened yet.

About: Max Borenstein has had the career path most writers dream about. Write a small script that makes the Black List. A couple of years later, write one of the biggest movies of the year (Godzilla), then get commissioned to write the sequel, then jump onto as many other high-profile pics as you can (Skull Island). But Borenstein got the memo. He knows that these days, if you want to buy that mansion in Hidden Hills, you gotta get into the TV game, and he’s doing so in a big way, attaching himself to one of the highest profile projects of the season – this sequel to the 2002 feature film of the same name. Minority Report will premiere later this year on FOX.

Writer: Max Borenstein

Details: 59 pages (Revised Second Network Draft) – Jan 8, 2015

I know you guys are all prepping for the Scriptshadow 250 Contest and therefore aren’t thinking much about pilots, but I’m telling you right now: Have some pilot ideas ready in case you win or place. The great thing about winning this contest is that you’ll have access to someone in the industry that you already know likes your stuff. So you should have ideas to pitch him if, or when, the time comes. And who knows? You could end up optioning another idea right then and there. Even if that isn’t the case, you’ll likely get other meetings around town where you’ll want to pitch pilot ideas as well. So don’t discount TV Pilot Tuesdays.

I still remember reading about the deal for Minority Report back in 2000. I thought to myself, “This has got to be the single greatest idea for a movie in history.” It was that high-concept hook every writer in town was looking for. A future where criminals were arrested for murders they hadn’t committed yet. And with Spielberg directing? And Tom Cruise starring? I’d been burned by high expectations before, but this felt expectation proof. How could the film go wrong?

Well, it did go wrong. Not in spectacular fashion. But watching that movie was an exercise in what could’ve been. In my opinion, the script made one enormous misstep. It took a very simple idea and complicated it. Murderers being arrested for murders they hadn’t committed yet? Genius! New-Age water-nymphs astro-projecting the future via tri-tandem mind links? Ehhh… not so much.

And yet I’ve never forgotten the film. Whether that’s because it left an impression on me or I’m still obsessed with what could’ve been, Minority Report remains an important film in the sci-fi universe. And for that reason, I couldn’t help but wonder what they were going to do with a Minority Report TV show. Maybe they were going to ditch the pre-cogs and go back to the core of the idea. Or maybe, with the extra time that TV provides, they would demystify our bathwater fortune tellers and actually give them purpose.

Lara Vega is a detective in the year 2065. That would be ten years after the “pre-cog” program went awry. For those who didn’t see the feature film, “pre-cogs” are special human beings blessed with the ability to see the future. The police used this power to predict murders and arrest the perpetrators before they could commit the crime.

But some high profile dude was using the program for his own gain so they had to go back to the old fashioned way of busting criminals – waiting until they killed someone and then using the evidence to catch them.

But what ever happened to those pre-cogs? Well, it turns out they’re quietly living amongst us. The problem is, their “gift” hasn’t gone away. They still see the future. But now, instead of helping, they must accept the horrible things they know will happen and ignore them.

Dash is one such pre-cog. And he’s trying hard to stick to the script. But lately, he’s been seeing a lot of murders, and he’s tired of standing by and doing nothing. So he decides to stop one. He gets there a fraction of a second too late, but runs into Lara in the process. After a little investigation, Lara realizes that Dash is a pre-cog.

Never one to play by the rules, Lara figures she can bring back the pre-crime program by herself. As in, she’ll secretly enlist Dash as her personal murder-predicting concierge. Since Dash is a water-nymph with all sorts of issues, he initially resists. But when he has a vision that the mayor himself will be killed, he decides to team up with Lara to save him.

Today I’m going to talk about something I don’t talk about much because it’s not related to story or character. But when the mistake is this egregious, I can’t ignore it. I’m talking about WRITING STYLE. Now usually when we talk about writing style, we talk about getting the most out of it – using it to bring the page to life – to show the world your voice (read any script by Brian Duffield to understand what this means).

But that’s only when you’re trying to write something edgy, stylistic or in-your-face. Most of the time when you tell a story, the goal of the writing is to be invisible. Yet for whatever reason, some writers become obsessed with choking their story with unnecessary style, killing any chance the story has at being enjoyable.

Now in small doses, style can be effective. Say you want to emphasize the sound of some nasty pipes inside a haunted house. Well then, CAPITALIZE THEM. Or maybe you want to describe an elaborate room full of eerie puppets in that same house. You might break protocol and write a couple of 6-7 line paragraphs so that you can lock the reader’s focus in. Or maybe you want to highlight a gun on the wall that will be used later by one of the characters. So you underline it.

Taken on an individual basis, all of these things are fine.

But they become a PROBLEM WHEN YOU start doing ALL OF THEM AT ONCE. This pilot was SO UNPLEASANT to read because every other page had a 7 line paragraph with tons of CAPITALIZED WORDS next to a bunch of italicized words followed by a bunch of underlined words. And let’s not forget all the………. ellipses………. and dashes ——– to make the read even more disjointed.

What really matters in writing is the story and the characters. But if the reader must go to war every time he reads a paragraph, he’ll never get a chance to appreciate either of these things.

I’ll never forget when a friend of a friend invited me to an LA Kings hockey game. This guy couldn’t stop bragging about his “floor level season tickets.” Okay, I thought, this should be fun. I get there, and the seats were right at the corner of the rink, where the glass is curved. It was like trying to see the action through a coke bottle. The final score was 2-1. By everybody’s account, it was an amazing game. But I didn’t see one minute of the action clearly. This is what reading Minority Report felt like.

Okay Carson. You’ve made your point. The writing was annoying. What about the pilot itself? Was THAT any good? Maybe the best way to answer that is to say it wasn’t bad. I mean, there’s a cool idea in here somewhere. A detective has herself her own personal future-murder detector. So each episode, I’m assuming, will entail learning about a future murder and Lara and Dash trying to prevent it from happening.

The problem is, I feel like we’ve seen this before. Wasn’t there that show on CBS a decade ago about a guy who gets tomorrow’s newspaper a day ahead of time? So he essentially finds out all the bad things that are going to happen and he must prevent them? And haven’t we seen variations of this idea a few times since then? Specific examples escape me, but my point is, the idea doesn’t feel very fresh. I mean heck, the film itself is 13 years old now.

The only unique aspect of the story is the pre-cog stuff, and as I stated earlier, that’s the stuff I was least interested in. But if you are a pre-cog fan, there’s a mystery subplot about where Dash’s pre-cog twin brother is. We later learn that he might be playing for the bad guys. That could lead to some interesting storylines.

But, unfortunately, Minority Report didn’t speak to me. It wasn’t the disaster TV remake that was 12 Monkeys or anything nuts like that. But there’s something missing here. A lack of freshness. Maybe they’ll find an awesome director with vision who can change that. I hope so. We’re in desperate need of some good sci-fi TV.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The first commercial break (end of Act 1) is a HUGE MOMENT for a TV pilot. You’ve managed to get people to tune into your pilot because they’re intrigued. That’s a tremendous feat. But these days, they’re ready to turn you off at the first commercial break if you don’t deliver. That’s why, especially in a clever-concept-driven show like this, you want to end the first act with some clever twist/surprise. You need to make it IMPOSSIBLE for the viewer to turn your show off. This is where Minority Report runs into its first issue. During the entirety of the first act, we keep seeing Dash’s drawings of the killer he sees in his visions. So the end of the first act has him bumping into Lara and dropping his drawings. She picks them up, sees that he might know the killer. Cut to commercial break. – Was there anything clever or surprising about this? Sure, Lara’s never seen these drawings before. But we have. Several times, in fact. If you can’t come up with something exciting to hook us at the very first commercial break, why would we think you’ll be able to keep hooking us as the show goes on? You absolutely have to nail that first commercial break to prove to the viewer that your show is worthy of their time.

Genre: Swashbuckling Adventure!

Premise: A rebel fighter is sent to the island of Jamaica in 1685 to spend the rest of his days as a slave. Instead, he becomes one of the most notorious pirates on the high seas!

About: The most recent word is that Warner Brothers wants to create Captain Blood in space with the Spierig Brothers (Daybreakers) directing. But it’s clear from this 1994 draft that they’ve been wanting to revive Captain Blood for much longer than that. What’s fun is that this was written by one of THE de facto writers of the 1990s era, Jonathan Hensleigh, who wrote Armageddon. Slap on some extra fun when you learn that none other than Frank Darabont rewrote this draft along with Chuck Russell, who directed The Mask and 2002’s The Scorpion King, and you’ve got yourself a cornucopia of script history.

Writers: Jonathan Hensleigh (Revised Screenplay by Chuck Russell & Frank Darabont)

Details: 123 pages – October 26, 1994 (Revised First Draft)

Arrrgggh.

Shiver me Oscar timbers. Get me some chum so I can get over the absurdity of a Birdman win. Okay okay, maybe I’ve been a little hard on the Birdman screenplay. But while I admit it’s got feathers, it’s also got some tar. Let me explain.

On the plus side, Birdman has a unique main character, it has the balls to tell its story in real time, and it takes chances (giving its main character telekinesis for no reason, for example). These are all things that should be celebrated in scriptwriting. However, the two things that remain the most important to me in a screenplay are a good story and a set of characters I care about. Birdman had neither. It was an experimental film first and a story second. And while I think it’s important that films like Birdman get made, it just didn’t resonate with me.

So where does that leave us today? I’ll tell you where. The 1930s! That’s when the original Captain Blood came out. And despite trying to bring the film back from the dead numerous times, it’s still failed to make it to the multiplexes. Today, we’re going to look at one of those attempts from 1994 – and try to figure out why they didn’t make the film then.

It’s 1685. Peter Blood, a surgeon, is fighting for the rebel forces, who are trying to dethrone the current English king (King John or King George or something). The rebellion fails and Blood, along with the remaining surviving rebels, is sent to Jamaica, where the Spaniards buy he and his crew into slavery.

Blood lucks out though, and somehow becomes the property of the Governor’s hot daughter, Arabella. You know you’re hot when even your name is hot. Blood and Arabella develop a flirtationship, which pisses off the local commander of the island, Major Edward Bishop, who’s been trying to get sum of dat action for awhile now.

Bishop tries to kill Blood a couple of times, but Blood is not your average movie hero. This dude makes all the other 90s heroes look like Chang from The Hangover. And when a pirate ship disguised as the King’s emissary attacks the island, Blood uses it as an opportunity to grab his rebels and take the ship for himself.

Soon, Blood is roaming the seas, looking to pirate himself some treasure (taking from only bad people of course). There are a couple of problems though. The most evil and terrifying pirate on the sea, Don Diego, kind of wants his ship back. And Bishop needs to save face with the King by getting the rebels back to Jamaica.

And let’s not forget, of course, about Arabella, who Don Diego has plundered for himself. Naturally, this is all going to collide in one big galactic swords and sandals battle. Will badass Blood kill the bad guys, get the girl, and keep on plundering? Or will he experience another 85 year drought before another movie about him can be made?

Goooooood plotting.

We don’t talk about this much but plotting – how you piece together your story – is one of the most important factors in keeping your screenplay exciting. If you go along one path for too long (the opening 40 minutes of Interstellar), the reader can get bored. It’s your job to maximize the emerging storyline’s structure in a way that keeps things moving along.

I LOVED how Captain Blood did this.

We started with this great battle of the Rebels taking on the Brits. The Rebels lose and, as punishment, they’re sent to Jamaica, where they’re then forced to work as slaves. Then a pirate attack on the island occurs. Our hero, Blood, uses the opportunity to steal the pirate ship and become a pirate himself. Then he’s off to get supplies for his ship. Then he must save Arabella. Etc. Etc.

The lesson to be learned here is that things were ALWAYS MOVING. Now every story is different. Some stories you’re going to stay in one place. But being a sea-faring version of Star Wars, this was the kind of script that needed to keep moving from one location to the next. And I don’t think a lesser group of screenwriters would’ve been able to do that satisfactorily. I could see them taking forever before our rebels were shipped off to Jamaica. And then, once in Jamaica, taking forever before Blood got his pirate ship. But Hensleigh (along with Darabont and Russell) stays everywhere JUST LONG ENOUGH to establish that place in the story, and then gets to the next section as soon as he can.

This actually leads me to a very powerful tool you can use in screenwriting. And it’s called “the disruptor.” The disruptor is any disruption you throw into a story that changes its course. I read so many scripts that just…. stay… on… the same… track… all… the… time. The story doesn’t evolve ever, and therefore we get bored.

The disruptor throws everything off, forcing your characters, and therefore your story, to act. The original disruptor is the inciting incident – the thing near the beginning of the story that rocks your main character’s world (Luke’s aunt and uncle are killed in Star Wars). But this should not be the end of your use of disruptors in your story.

In Captain Blood, just as I was wondering how long we were going to stay in Jamaica and where the story was going to go from here (it didn’t look like it could go in too many interesting ways), Hensleigh throws in the disruptor, the arrival of Don Diego’s pirate ship. IMMEDIATELY the story was exciting again. That’s the power of this tool.

Even beyond the plotting, this was just a really well-written screenplay. I think I was expecting some over-the-top 90s Bruckheimer thing. But the tone here feels surprisingly realistic for an adventure story. I would even argue that that may have been the reason it didn’t get made.

If you look at Pirates of the Caribbean, that whole franchise had a tongue-in-cheek component that made it more accessible to the masses. This is a little more hardcore, a cross between Pirates of the Caribbean and Master and Commander. Blood is an especially worthy hero. I usually see through these manufactured “I’m very aware I’m in a movie” characters. But Blood somehow feels like a real live hero. And you just don’t see that in adventure movies these days. Or ever, really.

The only weird thing about this script is the way it’s written. ’94 was still smack dab in the middle of the golden spec days – where spec screenplays were focused not just on becoming movies, but being entertaining experiences on their own. Captain Blood takes more time describing things and creating its mood and maybe that’s why it feels more substantial than a lot of the stuff I’ve been reading lately.

And the great thing about this script is that, because it’s a period piece, it doesn’t really need to be changed at all. This could still be filmed today without substituting a word. Of course, why do that when you can put it in space? But Captain Blood could be the “serious” alternative to the no-longer relevant Pirates franchise. I’d love to know if you agree. Because, yup, I’m actually posting the script. Enjoy!

Screenplay link: Captain Blood

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Is your screenplay starting to feel stale as it creeps into that second act? Disrupt it with a disruptor! Throw something unexpected at the characters that forces both them AND THE STORY to act.

P.S. Do you have the next Captain Blood? Enter your script in the SCRIPTSHADOW 250 CONTEST, go check it out here!

It’s finally here!

The official announcement of The Scriptshadow 250 Screenwriting Contest!

When I decided to put a contest together, I knew I wanted it to focus on one thing – getting the winner into the industry. Cash is great. A big flashy write-up on the site is great. But ultimately what matters most is that the writer begin their career as a professional screenwriter.

That’s why I brought in producer Lawrence Grey at Grey Matter. You may be familiar with Lawrence. He’s the only producer over the last couple of years to shepherd two 7 figure spec sales (Section 6 – about the origin of MI-6, and Winter’s Knight, the Viking-mythology St. Nick tale). First prize in the Scriptshadow 250 is that Grey Matter will option your script for 1 year at $5000, work with you on it (if it needs work), go to the studios and try to sell it, and, if everything works out, do everything in their power to turn it into a movie.

In addition to that first prize, we’re also looking for a handful of writers to join the Grey Matter writers group (which I’ll be involved in as well). We want to build a collective of writers who we can mentor, but who can also help mentor each other as they move up and into the industry. This contest isn’t just about anointing a winner and moving on. We want to build a career-long connection with these writers, and this writing group is the ideal way to do so.

Why does this contest trump every other contest out there? Because IT’S ABSOLUTELY FREE. You don’t have to save up a penny for it. The only payment you’ll need is the quality of your screenplay.

That’s because unlike other contests, I’ll only be accepting 250 scripts. I’m doing this because I didn’t want a bunch of mystery readers reading your screenplays. I want to be THE ONLY PERSON READING SUBMISSIONS. Unfortunately, the downside of that is that I have to limit the number of scripts I read – and 250 is that limit.

That means that instead of a simple submission, your e-mails will also be your pitch to me. You’ll send me the title, the genre, and the logline of your script, and then in up to 300 words, tell me why you believe your script should be accepted into one of the coveted 250 slots. There are no rules here. You can talk about whatever you’d like. But the competition will be fierce, so be persuasive.

Once I read all the scripts, I will submit the top 25 to Lawrence Grey, and Grey Matter COO, Ben Everard, and together we will decide the winner as well as the four runners-up (those who make it into the writers group). We really want to turn this into something bigger than your garden-variety screenwriting contest. We want to help you sell the script, we want to get the movie made, and we want to find great writers who are ready to take that next step.

The wonderful thing about this contest is that it starts this very SECOND. You can start submitting now. Below are the rules. If you have any questions, add them in the comments, and I’ll update the FAQ at the bottom of the post if need be.

PRIZES

GRAND PRIZE – $5000 1-YEAR OPTION WITH GREY MATTER AND ENTRY INTO THE GREY MATTER WRITERS GROUP

RUNNER-UP – ENTRY INTO THE GREY MATTER WRITERS GROUP (4 writers)

CONTEST GUIDELINES

1) Submissions begin right now (February 20th).

2) The deadline is 11:59 pm Pacific Time, August 1st, 2015. (NOTE: EXTENDED TO AUGUST 15TH!)

3) Send all submissions to Scriptshadow250@gmail.com.

4) Your submission should include:

a. The title of your script.

b. The genre of your script.

c. The logline of your script.

d. A pitch of why your script should be selected for the contest – up to 300 words.

e. A PDF attachment of your screenplay.

5) The winner (and runners-up) will be announced on December 1st.

RULES

1) Every writer may submit up to two screenplays. Please submit each screenplay in a separate e-mail.

2) You will receive confirmation if you’ve made it into the contest (top 250) by August 30th at the latest.

3) Eligibility Rule #1: Represented writers (writers who have a manager or agent) are eligible.

4) Eligibility Rule #2: You are not eligible if you have made more than $10,000 as a screenwriter. This does not apply to contest winners. You may still submit if you’ve won $10,000 or more in screenwriting contests.

5) Eligibility Rule #3: The script cannot have been submitted to a studio or have been under option by any person or entity (producer, production company, etc).

6) While we’re mainly looking for original properties, you may submit any adaptation of material as long as you have the rights.

LET’S FIND A GREAT SCRIPT AND SOME GREAT SCREENWRITERS. For a head start, check out yesterday’s post on how to win the contest!

FAQ

1) Is the contest free? Yes.

2) Can we submit scripts that we’ve submitted to other contests? Ideally, we’re looking for a new script, something that hasn’t been passed around the contest circuit. With that said, we want your best material, so submit whatever screenplay you’re most proud of.

3) Are Amateur Friday scripts or scripts we’ve sent to you for consultations eligible? All scripts submitted to Amateur Friday or for a Scriptshadow consultation WILL be eligible. Anything that’s made it to an Amateur Friday review has a better-than-average chance of making it into the top 250. However, if you received a “wasn’t for me” in your review, consider a big rewrite or submitting another script.

4) Can we send in our loglines then send the script later on? No. You must send a PDF of your script ALONG WITH YOUR SUBMISSION. You can’t test out a query, see if I bite, and then go write the script if I say you’re in. Your script MUST BE SENT along with your query.

5) I have a TV pilot. Can I submit that? This is a FEATURES ONLY competition. TV pilots are not eligible, though we’re thinking of adding pilots next year.

6) I live in another country. Can I submit a script? You can submit no matter where you live, unless you live in North Korea. Oh, what the hell, you can submit if you live in North Korea also.

7) Couldn’t you have bumped the option up to $10,000? Blame this on me. Grey Matter put up 5k, and I was going to charge a fee in order to raise the second 5k. But in the end, I wanted this contest to be free. So instead of charging an entry fee to solidify a 10k prize, I kept it free for 5k. It’s still a sweet deal, considering most places these days expect you to give them the option for free.

8) So the winner gets a 1 year option for $5000. What does that mean? This means that Grey Matter will pay you 5 thousand dollars to have the option to set up your movie for a year. If nothing comes of the option after a year (a studio does not buy the script), the rights to the script will revert back to you.

9) Wait, so do I get paid for the sale even though Grey Matter has the option on the script? Yes, if the script sells during the option, you will receive the money from the sale.

10) When do I agree to this 1 year option? The second I send my submission in? No. You are not agreeing to any option when you send in your initial submission. Once the official 250 entrants are chosen, each will be asked to sign an agreement stating that if they are the winning script, they will agree to the option.

11) Is it a good idea for me to give the rights to my script to Grey Matter for a year? If you’re an established writer who options material regularly, you may not need this contest. If you’re on the outside looking in with little-to-no contacts, being optioned by a legitimate production company is a huge deal that will benefit you in ways beyond the option itself. You’ll very likely end up with representation. Your representation will then send you on a series of general meetings that introduce you to the industry. In short, you’ll have a lot more opportunities as a writer. All on top of a great producer doing everything in his power to get your script sold and turned into a film.

Genre: Dark Comedy

Premise: After an internet date ends in the shocking death of a woman, a self-centered divorce attorney finds himself being pulled into her grieving family’s fucked up lives.

About: This script finished near the middle of last year’s Black List. Up to this point, Greg Scharpf’s claim to fame is that he’s been Matthew Broderick and Sarah Jessica Parker’s assistant.

Writer: Greg Scharpf

Details: 108 pages

Rising star Bill Hader for Scott?

Rising star Bill Hader for Scott?

Borrrr-ing.

No.

BORED.

Bored to tears.

In my search to find something – ANYTHING – good to read, I went through the first ten pages of 10 Black List scripts tonight, and you know what I found?

That I was BORRRRR-ed.

I was like: HELLLL-LOOOOOO???? Is anyone home??? Can someone direct me to Non-Lame Slugline Street??

Actually, you know what bothered me the most? Is was that they all started out so…. Same-y. Every script started with a “Boots pummel the pavement” or “We’re looking at JOE, 30, a boy in a man’s body,” or “Red wine swishes around a glass.”

I can’t even tell you what’s wrong with these sentences other than that they bored me. For a reader to open up another script and be greeted by yet another plain listless same-y sentence is a recipe for bore-sctucer sauce.

It reminds me that every single word you put down as a screenwriter matters. And not just what you put down, but how you put it down.

Look at the way I started this review. Different, right? It evoked a different kind of reaction than had I written full paragraphs like I usually do.

As a reader, I want you to stand out from the pack. And in reading these 10 boring openings to these 10 screenplays, I realized that there’s two key ways to do this. The first is through story. Make something happen right away that grabs me. It could be exciting, titillating, unexpected, weird, funny. But it needs to grab. The second is through voice. In reading these 10 openings, I noticed that not one of the writers truly distinguished himself with his style. It was all straight-forward text-book writing.

“One Fell Swoop” came the closest with its quirky setup, which is why I went with it. But I just want to remind everyone that that old sage advice of “pull the reader in immediately” is more relevant now than ever.

I can go watch fucking original programming on my PLAYSTATION nowadays. We’re a few years away from our soda cans playing shows (“PEPSI MAN!”). Keeping people’s attention with words is becoming harder and harder. So use your words wisely!

Lauren didn’t want her last words on earth to be, “I want you to lick my pussy.” But life has a sick sense of humor sometimes. Poor Lauren had lured a hot divorce lawyer home – our protagonist, Scott – in the hopes that he might be the one. But alcohol and poor judgment led her onto her balcony, which just happened to be 15 stories up.

Lauren got this weird idea that she’d sit on the balcony, spread her legs, and have Scott orally take care of her nether-regions. But then the railing broke, and poor Lauren went tumbling down to the Manhattan’s nether-regions.

The thing with Scott was, he just wanted to score that night. He didn’t even like Lauren, who was boring and narcissistic and liked The Bachelor. Yet somehow he ended up with someone stupid enough to sit on a railing that was 15 stories high in the sky.

Which would be traumatic enough. Except that after he explains the ordeal to the cops, Lauren’s parents show up, led by her bumbling spineless father, Harry.

Attempting to be cordial, Scott agrees with everything Harry says, inadvertently agreeing to lunch with him the next day. It’s here that Harry pours his heart out about his daughter, and Scott is stuck making up things to appease him – such as it was the best date he had ever been on. And what were her last words, Harry wants to know? Oh, something about how beautiful New York was at night, Scott tells him.

Lauren’s clingy parents insist on Scott being a part of the funeral, and the next thing Scott knows, he’s being recruited to come up with a eulogy. As if to make things even more complicated, Lauren has a twin sister, Jane! After Scott gets over the creepiness of the girl he watched die being rebirthed in front of his eyes, he actually starts to like Jane.

Will Scott come clean to the family and let them know that all he wanted that night was a piece of ass? Will he be able to tell Harry that he’s secretly falling for his other daughter? And will Scott learn, through this experience, that his job of being a soulless marriage executioner isn’t the best way to go through life? All of these questions will hopefully be answered in One Fell Swoop.

This was a surprisingly funny screenplay and that’s mostly due to Schrapf’s sharp voice. Remember that Black Comedy is the easiest genre to show your voice in, since “quirky-weird-funny” goes hand in hand with most people’s definition of “voice.”

The fact that Lauren’s claim to fame was her unhealthy obsession with The Bachelor was great. Lauren’s sad sack father crying every ten minutes was hilarious. And Harry’s blood-thirsty friend out for revenge on the railing code people evoked memories of a certain John Goodman character in a certain Coen Brothers film (yes, I’m talking about The Big Lebowski).

In a way, One Fell Swoop is like a reverse Meet The Parents. The big difference is that now you meet the parents after the girl is dead. Which is really weird when you didn’t even like her.

Where the script runs into trouble is trying to come up with reasons to keep Scott around. It becomes pretty clear around the page 40 mark that there’s no reason for Scott to be here anymore. But then Schrapf would write in some reason why he needed to stay, like Harry’s “Oh, I need help with the eulogy” subplot.

This is a mistake a lot of writers make. They don’t create an overarching scenario that keeps the characters around each other, thereby forcing them to repeatedly come up with reasons to make them stay.

Contrast this with Meet the Parents. Greg, the main character, is STUCK AT THIS HOUSE for the weekend. They’ve traveled here. So there’s nowhere for him to go. Thus, we never question why he must stay. These are little things to keep in mind when you’re writing.

Schrapf admirably puts everything he can into keeping the story going, however, despite it running out of juice. After all of the “help us prepare for the funeral” stuff dies out, he shifts over to the love story between Scott and Jane the Twin Sister, which is pretty good. Jane’s edgy alternative San Francisco vibe keeps the banter lively, and the stuff where Jane confronts a bitchy Christian frenemy who always made fun of her sister in high school resulted in one of the funnier scenes in the screenplay.

But I think the big lesson here is to make sure you come up with an idea that has enough juice to last an entire movie. One Fell Swoop kind of limps to the finish line since it explored the bulk of its concept before it hit the midpoint. Schrapf’s a funny writer so he distracts you from that fact. But you always want to come up with ideas that ramp up as they head towards the climax, not die down. Again, look at Meet The Parents. The sister’s wedding ensured that we were leading towards something that builds.

One Fell Swoop, while not perfect, brings us a writer with potential, which is mostly what you’re hoping for when reading a script near the middle of The Black List. To that end, this was a nice find.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Ideally, you want to work with big ideas that pack the pages. But if your script idea isn’t big enough to keep the story going on its own, you can use character subplots to keep the reader engaged. For example, if all Jane brought to the script was a love story, it wouldn’t have been enough. So Schrapf uses an old rivalry of Jane’s to build a subplot into the story, whereby Jane must go confront her rival. Character subplots can and should be used in any story, but in thin stories like this one, they’re absolutely essential.

Genre: Period/Drama

Premise: A look at the female perspective in one of the first ever towns in America.

About: If you don’t know Jenji Kohan by now, you don’t know cable TV. She started out by creating the largely successful Weeds for Showtime, then eclipsed the way more highly touted House of Cards to put Netflix on the television map with Orange is the New Black. Now she’s moving to HBO with her most offbeat and challenging show yet, “New World.” Jenji wrote the pilot for “New World” with brothers Bruce and Tracy Miller, who are brand new to produced television.

Writers: Bruce & Tracy Miller and Jenji Kohan

Details: 65 pages (Revised Prep Draft) 1/22/14

I find it fascinating just how far off the beaten path these networks will go for these upcoming television series. But if you’re HBO, Netflix, or AMC, you really don’t have a choice. Everyone’s using your model now – taking risks on unique provocative material – so you’re not the cool kid on the block anymore. In order to maintain your street cred, you have to go one step further. And that, of course, means riskier fare that is even LESS likely of finding an audience.

I love Jenji Kohan. I think she’s a great voice and is one of the best female writers in television. But I’m also a little scared of her. Especially with New World. There isn’t ANYTHING like this on television right now and the reason for that is because Jenji isn’t afraid to push boundaries. At the start, New World looks to be yet another boring documentary-masquerading-as-fiction account of America’s early past. But as you keep reading and finding out how fucked up everyone in this “world” is, you realize this is pretty challenging shit.

The year is 1692. Now it’s been awhile since my 7th Grade history class but I thought that Jamestown was America’s first town. Yet here, our featured town, Salem, is presented as the first city in the U.S.

If you believe the local pastor, Salem is a town rocked by sin. The women are lustful. The men are devious, and this is putting the town at risk of imploding. The sheriff is doing everything he can to keep people in line – even putting cages over the heads of women who gossip, but it doesn’t seem to be working.

15 year old Ann is our closet thing to a protagonist. She’s the daughter of an important man, Thomas Putnam, who’s at risk of losing everything he owns. He bought some land from the richest man in town, but that man is now disputing the sale, and his influence is likely going to win him the matter in court.

Ann, not wanting to end up on the streets and realizing the power of her burgeoning sexuality, uses the soft touch of her hand on a local gentleman’s manhood to coerce him into saying he witnessed the sale of the land in order for Thomas to win the case. We realize that Ann will do anything for her father – even if that same father will take advantage of her in ways that are beyond unseemly.

Meanwhile, across the forest in another village, 17 year old Mercy Lewis is kidnapped by some local Indians and subsequently raped. Then there’s Mary Sibley, who routinely gets a group of girls together to head into the forest, get high on opium, and engage in large female orgies, using anything to make the exploits more exciting, not excluding the occasional broomstick. Then there’s Betty, the pastor’s daughter, who’s going insane to the point where she imagines everyone is a crow.

Although it isn’t entirely clear where this is all heading, you get the feeling that Salem is a town on the verge of collapse if its leaders can’t rein in its people. And if the focus on Betty is any indication, that collapse may go beyond the physical into complete and utter insanity.

So let’s recap what we’ve got here. We’ve got incest. We’ve got underage sex. We’ve got lesbian orgies. We’ve got rape. Throw in insanity and drugs and you’ve got yourself one hell of a TV party.

As cheap as the use of lurid sex may sound, it’s essential for this pilot to work. If this is just going to be another “trying to survive in old times” TV show, nobody’s going to give a shit. You have to titillate. You have to challenge. You have to push boundaries. And really, it was the uncertainty of what fucked up thing was going to happen next that kept me turning the pages here.

That’s because there’s no real plot in this pilot and I’m a little disappointed in Jenji about that. If you look at Orange is the New Black, the pilot has a great storyline to it. An upper middle-class white woman is being sent to prison for a couple of years. That story is laid out for you before you even write a word (the fear of going to prison, the arrival, the scary inmates, the unique aspect of prison life).

New World is plagued by “Billion Character Setup Syndrome.” This is when you write a billion characters into your pilot, leaving you no time to actually tell a story. All you have time to do is introduce characters. And that’s usually boring, unless you can write the best character set-up scenes ever.

Now the leeway that Jenji has is that they’re going to put this on the air no matter what. So she doesn’t have to introduce a plot in the first episode. She can take as long as she wants to set everything up. But for the average amateur writer, I would never suggest this approach. You need to tell a story in addition to setting up characters.

Why couldn’t Jenji, for example, have followed the same model she used for Orange? There’s a boat that comes over from England in this pilot. Why not introduce us to a woman on that boat – maybe she’s posh, well-to-do – and we follow her (like we follow Piper) as she’s brought into this new terrifying foreign environment? That would’ve been the perfect way to introduce Salem along with the people in it.

Luckily, the characters are interesting enough that we eventually become engaged. It took me about half the pilot – but once I got to know everyone, I found them quite interesting. And we do have things happening. A young girl is kidnapped and raped by Indians. Characters are going insane. There’s a squabble over land. I just wish there was a bigger overarching plot to it all.

I will say this for those of you wondering how to write pilots that get people’s attention. Start out by putting MORE attention on character-creation than you would a feature. Remember, these people have to be interesting enough to last 75 episodes. So if you don’t like to do character bios, I’m afraid you’re fucked. You gotta get to know these characters intricately before you write them so that when you finally do put them down on the page, they actually have depth.

If all you know about a character is their name, they will come off as generic. But if, through your character bios, you find out that they’ve been raped by their father since they were seven, I promise you they’ll have an edge on the page. And that edge only grows the more you learn about them.

Once you have your characters – FIND A NEW ANGLE to come at your subject matter with. There is nothing you can think up that hasn’t been covered before by another show or movie. BUT you can still find fresh angles to cover those subjects from. Jenji and the Millers are looking at the New World from the female perspective. That’s the fresh angle and that’s what makes this pilot stand out.

New World is a strange tantalizing experiment, exactly the kind of thing you need to write to separate yourself from the competition. We’ll see if it finds an audience. But whether it does or not, it’s something to keep an eye out for.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Once you find your subject matter for your television show, FIND A UNIQUE ANGLE to explore that subject matter from. I’m not saying you can’t execute the hell out of a generic idea and make it work. It’s been done before. But you’ll more easily stand out if you can find that fresh angle.