Search Results for: F word

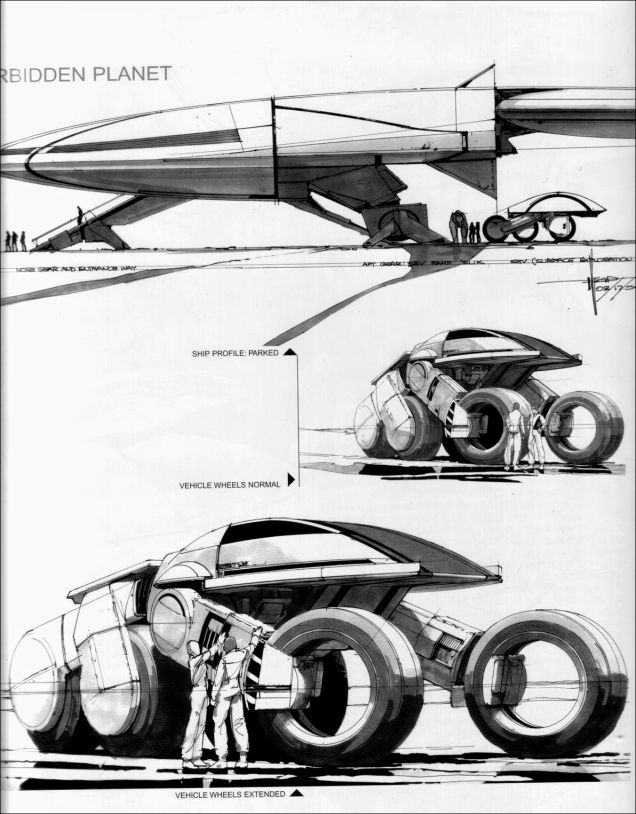

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: When a distant civilization calls out to earth, humanity sends a ship to the planet to make contact. But all they find is a deserted world.

About: The original 1956 film is a classic and the first film to portray humans travelling together in a space ship. As recently as six years ago, James Cameron was intrigued with the possibility of making Forbidden Planet. Furthermore, the writer, J. Michael Straczynski, in typical Hollywood fashion, wanted to make a trilogy out of the property. While the project died not long after, we must remember that nothing in the movie business ever really dies. I’m sure the project will rise again.

Writer: J. Michael Straczynski

Details: 122 pages

Confession time. I’ve never seen Forbidden Planet. A lot of people will tell you that the 1950s film “holds up,” but come on. It’s 1950s special effects with cheesy 1950s acting. You might as well take out the sound and add dialogue cards.

Now from what I understand, in the original film, this ship the “Bellerophon” went to this mysterious planet but disappeared, and so earth sent a second ship to go figure out what happened to the Bellerophon. Well, with Straczynski turning this into a trilogy, he’s decided to follow the Bellerophon’s journey first, and that’s what this draft focuses on. I didn’t find out about the trilogy plans until after I read the screenplay, but it makes a whole lot of sense now, for reasons I’ll get to a bit. But first, a summary of the story…

The plot is pretty straight-forward. Aliens send earth a signal, along with instructions to build a ship and come visit them. There’s one small glitch though. The end of the signal cuts out, indicating that something may have happened while sending it.

Humanity builds a big giant ship, headed up by Captain Thomas Stearn. There’s like a 70 man crew, but the other two important players are Dr. Edward Morbius, a linguistics expert, and his wife (in title only), Diana Morbius. We sense a wee bit of tension between these three as Diana may or may not be secretly involved with Stearn.

So anyway, they fly to this planet, Altair-4, and the entire planet is one big city. But an abandoned city. There isn’t a single life-form around. However, when we see them leave the ship, we zoom in to notice little nano-robots entering their mouths as they breathe.

They then find an old museum where a robot named RBI (who they nickname “Robbie”) explains what he knows about the planet. Unfortunately, he’s been shut down for 800 years, so he can’t tell them why no one’s around.

Eventually, our emerging villain, Morbius, goes AWOL, and due to some connection with the nano-robots inside of him and this fully automated city, starts to actually control the planet, and quickly works to prevent the Ballerophon from leaving. Stearn will have to figure out how to stop Morbius if he’s going to save his crew, a task that’s looking less and less likely by the minute.

So when I started reading this, I noticed something pretty quickly. It was a cool idea. I was into it. But the story started to drag. Despite actually getting to the planet by page 30, our crew was still exploring it on page 70.

There’s a period after your characters get to the “problem spot” in your story where they start looking around and trying to figure out what’s going on. Blake Snyder of Save the Cat fame liked to call this the “Fun and Games” section, but that doesn’t really apply outside of comedies and family fare. Instead, I like to call this the “Discovery” section. This is where characters try to “discover” what’s going on in the environment they’ve been sent to.

“Discovery” should really only happen for about 15 pages (which is the same amount of time, I believe, Blake Snyder gives for his “Fun and Games” section). After that, the audience/reader starts to get restless and wants change. Imagine, for instance, in Alien, if our excavation crew went down on the Alien planet for 40 pages as opposed to 15. We’d get bored, right? We need to get to the next phase of the story, which is to bring the alien back to the ship.

But even if you’re required to stay in the location with your characters, you need to start introducing some heavier plot developments than simply finding a robot and chatting with him (as was the case here). I know there are a lot of Prometheus haters out there, but you’ll notice that the Discovery phase didn’t go on for long before a series of intense plot developments started to occur.

And that was my big problem with Forbidden Planet. It was that classic issue where you can sense that the writer is spreading his story out. He doesn’t have enough meat to cook with. At first I was confused about this. I knew Straczynski was a good writer. So why was he doing this?

Then I read about the planned trilogy and it all made sense. And hence, we have one of the biggest writing problems plaguing Hollywood today. It’s hard enough to come up with a great two hour story. But if you tell the writer, before he writes a word, that he actually has to write a SIX hour story, this is what you’re going to get. Long-drawn out plots with not enough happening.

This is the same thing that happened with the Hobbit trilogy. I remember watching the second Hobbit movie, and there came a point in the middle of the film with this big water-rafting barrel floating set-piece – and I thought to myself, “Yeah, this is a big set-piece but where are the stakes? Why is this important for the story?” It was empty because you could tell the writers were trying to cover the fact that they didn’t have a lot of story to begin with. The strategy, then, was to distract you with a big fat set-piece.

The solution to this problem is to always think of your script as a single script, even if you do plan to continue it with additional movies. Try to make it the best actual story on its own.

But there’s a bigger lesson here for screenwriters. And that’s to keep your story moving quickly. One thing I’ve found with young writers is that whatever you think is “fast-paced” is actually a lot slower on the page. It takes years and years for writers to actually understand how fast their story is coming across on the page.

So focus on moving the story along faster than you believe you have to. And that means introducing major plot points that push the story in new directions (a dangerous face-hugging alien on one of your characters) rather than small plot advancements that only have a minor effect on the story (finding a museum on your mysterious new planet).

Or, if you want me to put it simply: More shit needs to happen.

It’s kind of funny that we’re discussing this in the wake of a review about scripts that are ‘too complex.” But that’s not really what we’re talking about here. Complexity has little to do with writing bigger plot points that happen more frequently, which was the problem with Forbidden Planet. This script needed more meat. Maybe in future drafts, they’ll slaughter more cows to get it.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you feel like you’re biding time in your script, you probably are. Think about that for a moment. If you ever feel like you’re adding scenes to just keep the story alive and keep it going, those scenes will be dead on the page. Every scene should move the story forward in some purposeful way. If you ever feel like you’re biding time, go back to the point in the script where that “biding” started, and start over again.

Genre: Dark Comedy

Premise: The discarded heir to a billion dollar fortune decides to kill all his family members to inherit the money.

About: Screenwriter Ford is a new kid on the block, but that didn’t stop him from landing at number FIVE on the 2014 Black List. He’s repped at UTA and managed by Black Box Management. He also had a short film play at Sundance in 2010 called Patrol.

Writer: John Patton Ford

Details: 126 pages

I’m thinking Ryan Gosling for this one.

I’m thinking Ryan Gosling for this one.

Wow.

This is quite the screenplay. I can’t remember the last time I finished a script so… angry.

Not because the script is bad. Oh no, this is not Moonfall 2: Moon Tornadoes. Far from it. This script purposefully orchestrates your anger. To that end, it’s a success. But man, it’s not an easy success to embrace. Never has a villain seemed so casual yet ignited feelings of such rage in me.

Before you read it though (for those who have the Black List scripts, you have this), note that it’s not an easy script to get through. You’re not going to find me supporting its excessive 127 page girth. But I can promise you this. This parallel world version of Wolf of Wall Street is crafted well enough to leave you feeling rewarded when you finish. Even if that reward is a kick to the groin.

When we meet Becket Rothchild, he’s on Death Row. In fact, he only has hours to live. So he’s giving his “confession” to a priest, a confession that doubles as our narration of the story. Becket explains that 30 years ago, his mother, a teenager at the time and member of the Rothchild’s, one of the richest families in the world, got pregnant.

Her father told her that she could either abort the baby or leave the family and never come back. She decides to leave, which led to Becket’s birth, and the two hustled through life with no money at all until his mother died of cancer, a death that could have been prevented with some financial help from the family. But even then, her father turned his back on her.

This is what led to Becket’s hatred of his family, and kickstarted his desire to kill each and every one of them. Truth be told, revenge wasn’t the only reason Becket became a killer. Becket liked the idea of having all that money. As he tells us at the beginning of his narration, that old saying that money doesn’t buy happiness is bullshit.

There are nine Rothchilds to kill and they include frat douches, hipsters, reality star twins, and the big tuba himself, the man who kicked his mother out. Becket’s murder weapon of choice is a bow and arrow but the Rothchild killings come in all shapes and sizes, including poison, fire, even dynamite!

As Becket gets closer to his goal, his childhood crush and now bitter enemy, Julia, wises up to his plan. She blackmails him, telling him that if he doesn’t give her 3 million dollars, she’s turning him in. As we all know, a blackmailer never stops after they get your money. They always keep coming back for more. And Julia does come back for more right when Becket’s at his lowest point. (spoiler) It turns out she has something that can set him free. However, he’ll need to give her the entire fortune to get it. Whatever will Becket do?

Before we get into the meatier aspects of the screenplay, I want to point out a “show don’t tell” moment to remind all the screenwriters out there how important it is to look for these opportunities.

Early on, Becket’s mother becomes sick with cancer. After exhausting all their options, they make one last Hail Mary pass and return to Daddy Rothchild to ask him for money. Now, I want you to think about this scene as if you were about to write it. What would you write?

You could, of course, write a scene where Becket’s mom sits down with her father and pleads for his help. The high stakes of the situation would dictate, at the very least, a decent scene. But since the directive of the scene is so simple (she asks, he says no), it’s the perfect scene to look for a “show don’t tell” alternative.

And that’s what Ford gives us. He shows Becket wheel his mother up to the mansion in a wheelchair, Becket talks into the call box, and then the gates close on the both of them. In a matter of a few lines, you’ve given us a much more powerful version of the scene (and in 1/10 the space it would’ve taken to write a dialogue scene).

I don’t know what it is but there’s something about an ACTION that really does speak louder than words in screenwriting. A huge iron gate closing on this helpless soul packs so much more punch than a series of (likely) predictable lines between daughter and father. As writers, you should always have your “show don’t tell” goggles on when writing. Always look for those opportunities.

Now, as for the script, I’m not going to pretend this was a smooth ride from start to finish. Once I realized that Becket had to kill nine people, I was like, “I have to sit around and wait for this guy to kill NINE PEOPLE!?” It’s hard enough to make one killing interesting. How is this guy going to keep our interest for nine?

Indeed, once we got into some of these middle-killings, I started getting restless. That 127 number staring at me from the top of the document wasn’t helping. But I’ll tell you when things changed for me. There’s a moment where Becket is about to kill the Televangelist Rothchild. He poisons his glass when he turns away. But when Rothchild turns back, he says, “So which poison did you use?” He then turns the tables on him and ties Becket up.

It was the first time I was legitimately surprised by what happened. Up until that point it was: Meet a Rothchild, spend a shit-ton of time with him, and FINALLY kill him. This one caught me off-guard. And it reminded me that one of the reasons you set up goals in screenplays, is to create expectations. You say to the reader, “Hey Reader – my character is going to go do this now.” The reader then relaxes and says, “Okay, let’s watch the character do this now.”

Once you lure them into that sense of security, you turn the expectation against them. That’s exactly what happened here. We figure, hey, he’s going to kill the televangelist just like he’s killed everyone else. But now the televangelist flips it around and the hunter becomes the hunted. Building expectation is a powerful tool. But it only works if you fuck with the expectation.

And yes, I get that to fuck with the expectation, you first have to lure the audience into a sense of security, which is why Ford would argue the previous Rothchild killings needed to go according to plan. But there were a few too many of them and each of them lasted a few scenes too long. We needed to get through that section quicker. I’d even argue that we don’t need 9 people. We could get away with 7.

Anyway, after that, the script was less predictable, and the increasing frequency of our serpentine villain, Julia, added another x-factor to the story. We were no longer on that predictable “get to know a Rothchild, then kill him” train. We were on busses, planes, sidewalks, bikes. Shit, we were in an Uber at one point. All of this made me less sure of where the story was going. I was kind of surprised, being so apathetic at the midpoint, how into the ending I was. And when that big bombshell hits, it’s something else. As in, it kind of makes you want to kill yourself.

“Rothchild” left me with mixed feelings but they were feelings nonetheless. I’m still thinking about it. And that’s usually a good thing.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: We’ve discussed the page number thing to death. But if I can, I’d like to recap. It’s true that page length doesn’t “really” matter. A well-written 120 page script can read like it’s 90 pages and a terribly written 90 page script can read like it’s 140 pages. Here’s why keeping the page length down helps though. It forces you to make tough choices – to cut out stuff unless it’s absolutely necessary. A lot of writers are the equivalent of motor-mouths. They like to hear themselves type. Well, as you know, it doesn’t take long for somebody to eventually tell those people to shut up. Don’t be a screenwriting motor-mouth. Choose your words carefully.

What I learned 2: A serial killer main character gives your script a 20% better chance of getting on the Black List. I’m not kidding.

Note: The Scriptshadow Newsletter was sent out last night. If you did not receive it, check your SPAM and PROMOTIONS folders. If you want to sign up for future newsletters, you can do so here. Hope you enjoy it!

Genre: Animation

Premise: Woody, Buzz, and the gang are stuck at Andy’s spooky grandma’s house for the night, where the toys start disappearing one by one.

About: After Toy Story 2, back when Pixar and Disney were going to break up, Disney still would’ve owned the rights to the Toy Story franchise. They went back and forth between whether to make another Toy Story feature or to send the franchise into direct-to-video purgatory. As such, they wrote several versions of Toy Story 3. I thought I’d be reading the recently talked about version of Toy Story 3, which had Buzz Lightyear being recalled to Taiwan, but this draft of the story appears to precede even that. Interestingly enough, you can see the seeds of what would eventually become some of the major sequences in the official Toy Story 3.

Writers: Cheri and Bill Steinkellner (Revisions by David Guion and Michael Handelman)

Details: 104 pages – June 8, 2005 draft

I love reading early drafts of famous movies because you can really see the writing process in action. When you’re writing your own script, searching for that perfect plot point or memorable character, it can be hard to see the forest through the trees. Only by looking at a great movie and then going back to the early drafts where it wasn’t so great, can you see the key decisions the writer’s made to make it work.

In this case, we went from Grandma’s haunted house to a pre-school prison. On the surface, this doesn’t seem to be that big of a deal. Both locations offer plenty of hijinx and opportunity for adventure. But later I’m going to tell you why the pre-school was a waaaaay better option, saving the Toy Story franchise from going into the toilet.

Toy Story 3, the 2005 version, starts the same way Toy Story 3 the 2010 version starts, with the toys playing in Andy’s imagination. The scene is a toned down version of the huge opening from the official film. Afterwards, the toys learn that Andy’s room is going to be redecorated, and they’ll be packed into a box and sent to Grandma’s with Andy for the night.

Once at Grandma’s, a big scary Victorian mansion, the team meet two new toys, a sniffling badly cobbled together excuse for a sock monkey named Gladiola, and Jack Challenger (otherwise known as Hee-Hee), a sock monkey who’s been on more adventures than Indiana Jones.

Hee-Hee is perfect in every way and quickly wins the toys over. But Woody has some reservations about him. He can’t put his finger on it, but he’s seen this toy before. He just can’t remember where.

As the toys come up with a plan where Hee-Hee will stay with them so that Andy accidentally takes him home with them the next day, members of the group start disappearing, starting with Woody’s horse, Bullseye. This, of course, makes Woody even more suspicious of Hee-Hee.

Rumors start flying that Andy’s room redecoration will be accompanied by a more sophisticated lifestyle, and that only two of the toys will be returning. This results in everyone pointing the finger at the notoriously jealous Woody, who they believe is offing the toys one by one so that he can be one of the two toys.

As the group heads deeper into the spooky house to find the missing toys, Woody must find a way to prove his suspicions true, that Hee-Hee is somehow behind this. But the more he digs, the more it’s starting to look like someone else is involved.

One of the first things you notice about the 2005 version of Toy Story 3 is the opening. It’s very similar to the eventual movie. The toys are on a train, heading towards a giant canyon, and it’s all happening in Andy’s imagination. The big difference is scope. This version seems neutered, not as imaginative. For example, there’s no giant spaceship that comes in at the end. It’s like the writers began the idea and then got bored with it.

Strangely enough, the ending is the same as the official Toy Story 3 ending as well. Our toys get stuck in a garbage truck and are heading to the landfill. But again, it’s a neutered version. They never get to the landfill.

I can’t stress how important of a lesson this is. Big set-pieces require imagination. They’re, in essence, their own stories, and the first versions of these stories are going to be pale imitations of the final product. Every time you come up with a set-piece, put it down, and the next time you come back to the script, look for ways to make it more imaginative. Afterwards, put it down, come back weeks later, and look for ways to make it more imaginative. If you don’t do this, you’re going to end up with the garbage truck version of the Toy Story 3 climax as opposed to the huge multi-location landfill version that was in the final film.

Now, let’s talk about why this script was scrapped in favor of the eventual pre-school storyline, cause this is a super important lesson for screenwriters as well. Put simply, the Grandma storyline doesn’t take advantage of the specific concept of Toy Story. Toy Story is about toys that come to life. Throwing those toys into a “haunted” house doesn’t take advantage of that in any specific way. In other words, you could put any characters in a haunted house and it wouldn’t be much different.

When you have an idea, you want to find a story that takes advantage of that concept in as specific of a way as possible. Putting toys in the hands of young kids is a storyline that much more specifically takes advantage of the toys-coming-to-life concept.

And this lesson isn’t relegated to the concept only. It’s something you should be thinking about with every aspect of your story. For example, a few weeks ago, I read a superhero script where the main character’s power was his ability to use fire. The big climax of the script? A shootout on the top of a building. I explained to the writer that if the main character’s big power is his use of fire, then you need to build a climax around that specific idea. Maybe he’s in an oxygen-deprived environment where he can’t use his fire. Or maybe there’s water preventing the use of fire somehow. But whatever it is, it has to be more specific to the story being told. It can’t just be a random shootout scene, no matter how cool the location is.

The 2005 version of Toy Story also violates one of the big tenants of Pixar storytelling. There’s no theme! It’s just a goofy little story about toys going to Grandma’s haunted house. There’s no bigger message – no deeper feeling when you finish reading it. The real Toy Story 3, however, is about moving on into that next phase of life, something that directly came about because the story focused on a more concept-specific idea in the pre-school.

Another thing you notice by reading this version is how forced all the motivations are. You’ll see this a lot in early drafts (or Amateur scripts, where writers don’t write enough drafts). The writers are clearly trying to come up with reasons to put their characters where they want them to be, but aren’t doing a good enough job of it.

Andy’s room is getting redecorated? That’s a pretty lame motivation to send the toys out of the house. I mean, why not just put the toys in another room? Consider the motivation for the toys leaving in the real Toy Story 3 – Andy’s leaving for college. That’s a much bigger and more realistic motivation.

Motivations are one of those annoying things that take multiple drafts to get right. If you ignore them, they’ll look like this: clearly forced writer plot points to get the characters where they want them to be. Don’t stop rewriting until all the motivations feel natural.

As much as I wanted to read the Toy Story 3 Taiwan version, this was a great reminder about the power of rewriting.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: How big does your rewrite need to be? If your execution is not taking specific advantage of your unique concept, as was the case here, you’re looking at a page 1 rewrite. If you were smart enough to make the story concept-specific, however, your rewrite should be much more manageable.

I was going to do my yearly post of the best movies of the year, but you know what? I don’t wanna. “Best Of” lists are boring to me right now. And if I’m bored, then my posts are definitely going to be boring. So instead, I’m going to share some screenwriting advice with you. Now that excites me. Helping all of you become better writers. For those who just have to know, however, here are my Top 10 films without explanation.

10)Captain America: Winter Soldier

9) The Equalizer

8) Blue is the Warmest Color

7) Guardians of the Galaxy

6) In a World

5) John Wick

4) Gone Girl

3) The Skeleton Twins

2) Philomena

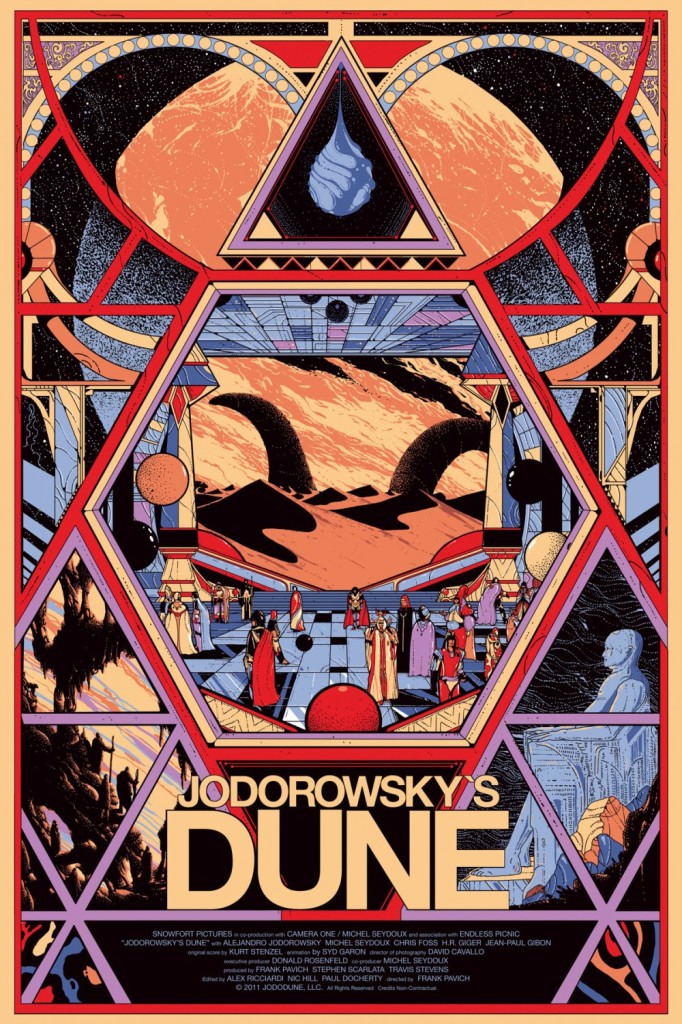

1) Jodorowsky’s Dune

Did not yet see: Nightcrawler, Boyhood, The Imitation Game, Foxcatcher, Lucy, Whiplash.

Now let’s talk about something that can actually help you. How bout a hefty dose of DIALOGUE ADVICE? Yeah! Nobody offered you that over the Christmas holiday, did they? You see, the other day, I was giving notes to a writer, and the dialogue in the script wasn’t up to par. Dialogue is always the hardest thing to help a writer with because it’s the subtleties that make it or break it. And most subtleties are intrinsic, making them hard to dissect and explain. This is what people mean when they say some writers have an “ear” for dialogue. What they really have is an ear for the subtleties of conversation.

So I had to take a few hours off, go through old sets of notes, pick out tips I’ve given before, look for new solutions specific to this writer’s problems, and package it all in a way that would help this writer dramatically improve his dialogue. The end result was more comprehensive than I expected, so I thought I’d share it with all of you. With that, here’s what I wrote…

The big weakness here is dialogue. There are too many on-the-nose, melodramatic and cliché lines. Here’s an example from Hunter and his son, Nicky (note to readers – part of the backstory here is that Hunter’s wife died).

Nicky: “Wish I could’a protected her that day…”

Hunter: “Me too, Nicky… me too.”

Let me ask you this. Is there any doubt that father or son wished they could’ve done more to save mom? Of course not. Therefore, to say it out loud is the definition of “on the nose.” This is followed by an extremely cliché echo-line. “Me too, Nicky… me too.” The echo-line has been used so many times throughout history that by this point, it’s only used as parody. I’ve personally seen the guys on South Park use it endlessly. Stay away from on-the-nose lines (characters saying exactly what they think/feel) and any line you’ve seen used more than a handful of times in other movies/shows.

Here’s another line (note to readers: our protagonist, Colin, accidentally killed a child while trying to save a group of people. Claire, our romantic interest, has just tried to convince Colin that it was an accident and there’s nothing else he could’ve done).

Colin: “He was just a little boy, Claire! His whole life ahead of him.”

Take note of how familiar and melodramatic this line is. It feels like something out of a soap opera. Also, once again, we know he was a little boy. We know he had his life ahead of him. Therefore, stating it out loud is on the nose and obvious. If you find your characters saying exactly what they’re thinking, exactly what they’re feeling, or anything that’s obvious, you’re probably writing bad dialogue. So how do you make this line better? In this instance, I wouldn’t have had Colin respond at all. As Claire tries to convince him it was an accident, I would’ve had him take it in. A look of frustration or disagreement, then, is all you need to convey his feelings on the matter. Often times, the absence of dialogue is the best dialogue option.

Overall, the dialogue here needs to be more unpredictable. It needs to be more natural and messy. Moving forward, I would suggest studying dialogue on a much deeper level. Start by writing down all your favorite dialogue-centric movies, then reading those scripts and noting where you liked the dialogue, then trying to figure out WHY you liked the dialogue. For example, a writer whose dialogue I’ve come to enjoy always inserts a unique phrase where a generic one would typically be. So instead of writing, “Joe went bar-hopping,” he might write, “Joe’s down at the strip of broken dreams.” Yet another writer reminded me how important specificity is when it comes to dialogue. A character shouldn’t say, “I need cereal.” He should say, “I need Tony the Tiger.” Paul Thomas Anderson, who many consider to be a dialogue master, says he rarely lets his characters finish sentences. He constantly has them interrupting before the other character finishes, as that’s more like real life.

I would go to coffee shops and eavesdrop and write down, verbatim, what people are saying to each other. Pay attention not just to what’s being said, but what’s being implied, aka, the subtext. “That’s a nice new purse,” doesn’t always mean, “That’s a nice new purse.” It might mean, “Looks like your sugar daddy’s treating you well.” Compare all this dialogue to your own dialogue. Figure out why yours doesn’t have the same naturalism.

I would spend every day writing a few practice dialogue scenes. Experiment. Take chances. Be creative. For example, write an entire scene with dialogue you’ve never heard before. Write an entire scene focused on subtext. Write an entire scene focused on suspense. Compare your scenes to scenes from professional scripts and note the differences. Pay specific attention to word choice. What words are the professionals using that you’re not?

Try to create scenarios where there’s conflict or tension between characters, as both result in more interesting conversations. Create secrets for your characters, so there’s subtext to what they’re saying. For example, in your script, Claire tells Colin right off the bat that she’s dying. Instead, what if you only give this information to the audience, and now when she meets Colin, she DOESN’T tell him she’s dying. Now the dialogue will be a lot more interesting. We’ll fear for Colin as he falls for Claire, knowing he’ll be devastated when he finds out the truth. Dialogue is one of those things, unfortunately, that doesn’t have a quick fix. It’s the culmination of a lot of small discoveries. But it’s not an area you can hope readers will overlook. Bad dialogue is one of the easiest ways to identify an amateur screenplay, so you have to put a lot of effort into getting it right.

I’m going to mix it up this year with my “Worst of the Year” list and not only include the “worst” films, but films that were the most disappointing as well. The idea here isn’t necessarily to highlight the truly worst movies of the year. Those would obviously be films like Kirk Cameron Saves Christmas and Winter’s Tale, but since there’s no reason to see those movies to know they’re bad, there’s really no reason to include them.

As for my criteria for deciding the “worst of the worst,” most of it comes down to bad writing (surprise surprise). And bad writing can be broken down into three categories: A) Writers who don’t know how to write. B) A lack of effort in writing the screenplay. And C) The people involved in the film don’t care about the script.

What really gets me is B and C. It’s not really a writer’s fault if he’s bad and someone hired him to write the movie. If he’s giving his best effort, I applaud him. But if you didn’t try hard when writing a movie? Or if the people involved don’t think a screenplay is important enough in the first place? That’s a cinematic criminal offense. So those movies always get the brunt of my frustration. Let’s take a look at the nasty cinematic offerings that 2014 gave us and celebrate their journey into cinematic obscurity.

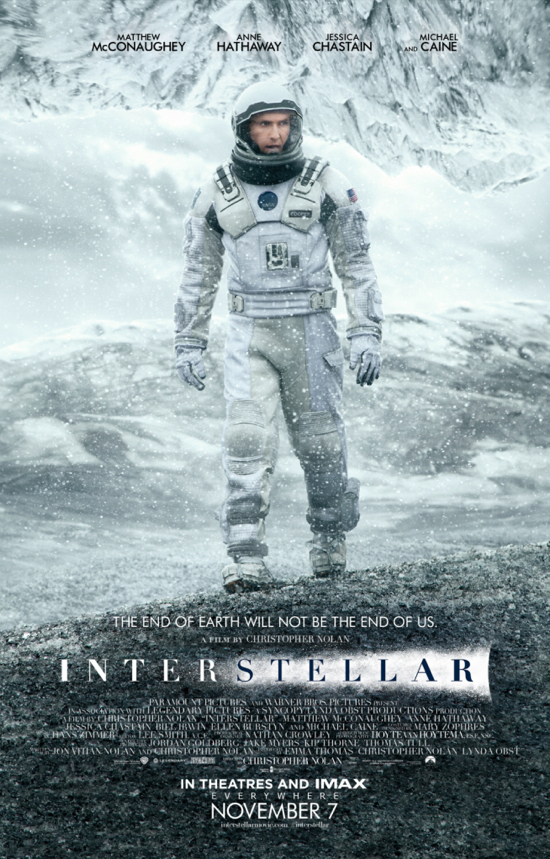

10) Interstellar (disappointment) – I avoided all spoilers going into this movie, expecting it to be the culmination of everything Christopher Nolan had learned up to this point as a filmmaker. The scope couldn’t have been bigger. Space. The final frontier. Matthew McConaughey. Interstellar was going to be amazing. That was the plan, at least. Instead, I got muddled pseudo-science, a sloppy narrative, and an ending so ludicrous even the actors looked confused about what was happening (“I’m in a black hole talking to the past. Oh wait, now it’s 50 years later and Saturn has a space station. What????”). The Nolans needed to be put in script detention during the writing of Interstellar but no one had the balls to do it.

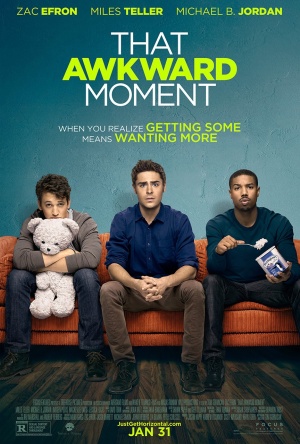

9) That Awkward Moment (bad) – Here’s some screenwriting advice. If your screenplay is so devoid of an idea that you have to title it, “That Awkward Moment,” you probably shouldn’t make the movie. There’s something in screenwriting known as a “concept.” It’s kind of everything that the movie hangs on. Concepts need to be big and clear. What does “That Awkward Moment” mean? Someone has an awkward moment with someone? You’re going to base an entire movie on that? When movies don’t have focus, they fall apart quickly. Watching this film was a lot like watching a bunch of people dancing without any music. It was ugly.

8) Wish I Was Here (disappointment) – I wish I wasn’t here. Maybe I drank the Garden State kool-aid too fervently when Zach Braff’s first film came out, but I liked it. The main character was on a mission. He was doing something. The film had a point! Wish I Was Here, however, was just a really sad film with people talking about how their lives didn’t turn out the way they wanted them to. The script was mired with more melodrama than 20 years of televnovellas. It was peppered with scenes that didn’t push the story forward. Story threads would show up then inexplicably disappear (the home school stuff). As if a bunch of people mumbling about how shitty their life is isn’t bad enough, we had a cancer-stricken father to deal with. Ugh. This was a brutally bad movie.

7) Annabelle (disappointment) – Isn’t the defining pre-requisite of a horror movie that it be scary? I hate to use dumbed down language here, but this was really dumb. And it was cheap! From the actors to the set design to the limited locations, everything here felt like they were cutting corners. Some scope, some original ideas, and some scares would’ve gone a long way to making Annabelle watchable, but nobody appeared to be interested in doing so.

6) The Amazing Spider-Man 2 (bad) – The Amazing Spider-Man is still trying to be 2002 Spider-Man, when all the rest of the super-hero world has moved on. Whereas franchises like The X-Men and Captain America seem to be making bold choices, pushing their genres in new exciting directions, Spider-Man’s still holding on to shoddy special effects, goofy characters, and sloppy narratives. That may have been fine when Spider-Man was the only game in town. But the audience’s tastes have matured, and Spider-Man hasn’t matured with them. I remember a scene in this movie where Spider-Man sneaks into his room with Aunt May about to catch him,Peter still in his Spider-Man outfit, and I just thought to myself – We saw this exact same scene less than a decade ago. Move on!

5) Obvious Child (disappointment) – There was something so overtly off-putting about this movie that I’m still thinking about it 4 months later. For a film that purported itself to be “important” and “thoughtful,” I was baffled that roughly half the movie had to do with shit. Really? Does every other joke in your film really need to be a shit joke? It was in such poor, but more sadly, lazy, taste, that it was hard to take anything about the film seriously. And the main character was just… I don’t know, a weird combination of annoying and sad. Watching her do her stand-up that wasn’t stand-up at all but rather her talking about how shitty her life was – I guess that was kind of the point, to show her be vulnerable and different – but boy did it make me a) depressed and b) hate her. The only thing obvious about this was its suckiness.

4) The “Blended” Trailer (bad) – That’s right. I’m putting a movie on here that I haven’t seen. Sound unfair? Sorry, but it’s an Adam Sandler movie. Seriously, go watch this trailer now to see how terribly written it is. Take note of how much exposition they need just to have the two main characters say: “WE’RE GOING TO AFRICA!” You could’ve cut 90 seconds out of your trailer and 90 minutes out of your movie had you just showed the two families on vacation running into each other in Africa. Instead you have: “My boss canceled and so he needs someone else to go and then you need to go fill in for that other person, but wait, your boss is my boss, oh wait, I’ll call him, zoinks, turns out you know him too? That way if you go and I go… On my god, WE’RE GOING TO AFRICA!” I’m hoping these leaked Sony e-mails finally wise Sandler up to the fact he’s making the worst movies in Hollywood right now. It’s the intervention he’s needed for a long time. If it’s successful, maybe we’ll never have to hear the words “WE’RE GOING TO AFRICA!” again.

3) Deliver Us From Evil (bad) – I don’t… I can’t… I’m trying… I don’t know how to describe this movie. I thought I was going to get some cool freaky religious cult horror film. Instead, I got a man hanging out at the zoo for a couple of hours. The only common thread I could find in the film was a pale-faced bald guy who sometimes hung out at the zoo. There was also something about a cave in Iraq. Oh, and this is all based on the “real life experiences” of some New York cop. I don’t know what makes me more sad – this film or Eric Bana needing to take roles like this.

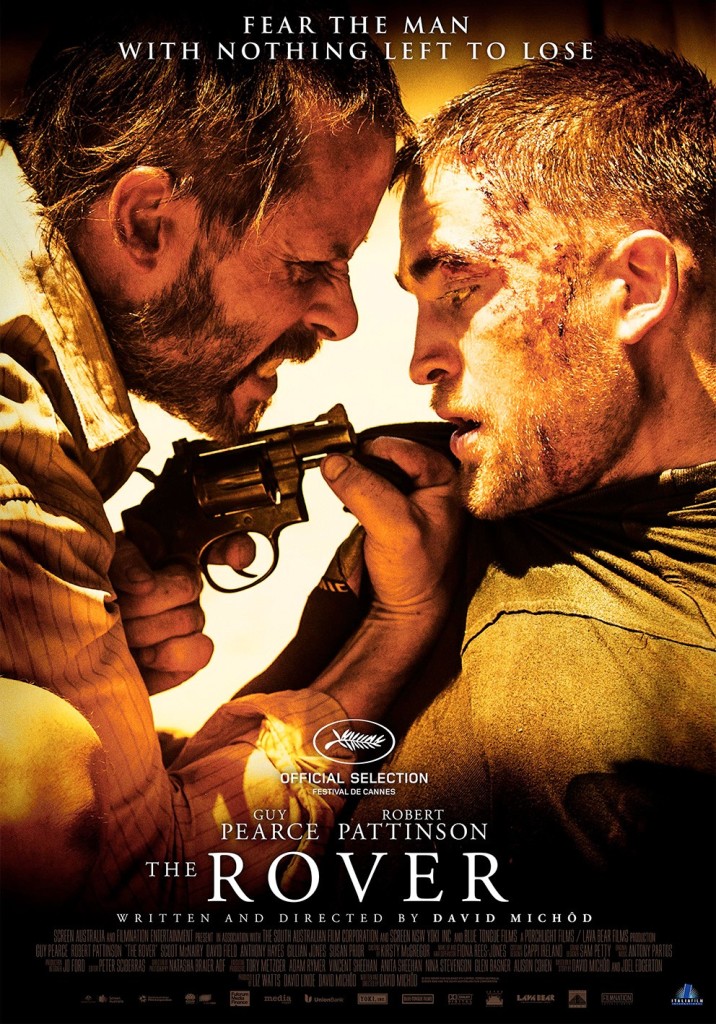

2) The Rover (disappointment) – What? Was? This movie? Let me get this straight. You set your movie in an apocalyptic future. And then the story you decide to tell in that future is, a man gets his car stolen and decides to chase the people who stole it from him? That’s it???? But wait. It gets better. This world is riddled with deserted cars. So the man could’ve just found another car within a few hours. But no. He wants this car! Oh, I know what you’re thinking. The car must be special then. Like a 1959 Firebird or some other unique car, right? Nope. It was a garden variety SUV. I was so confused by the anorexia of this premise that I waited around as long as humanly possible, positive that an actual plot would surface. Nope. As a director, you get to make 1 movie every 3 years. With that choice, this director decided to do a movie about someone who chases someone else over a car. I’m speechless.

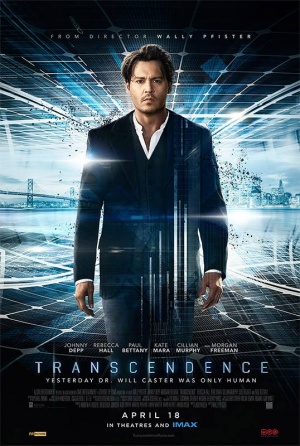

1) Transcendence (disappointment) – I’m still not entirely sure how this spec script worked so well and the movie didn’t. I know the film never felt like it got out of first gear. It kept revving its engines and revving its engines, hinting at a big next level, but it never came. There was also an inexplicable stillness to the film. Once we got to this town, our characters seemed content to just… wait around. Nobody was doing anything, particularly our heroine, whose sole purpose seemed to be to wait for Johnny Depp to talk to her. And to be honest, I don’t even know if she was our heroine. By the middle of the movie, so few people had purpose, that it wasn’t clear who our hero was. I’m not going to say that Transcendence killed the spec script, but it certainly tried its best to.