Search Results for: F word

A secret about screenwriting that only the tippy-top screenwriters know

One of the weirder things I’ve learned about screenwriting over the years is that there are things that work in a script that don’t work in a movie and there are things that work in a movie that don’t work in a script. Understanding why this bizarro process takes place can help you elevate your scenes – especially your dialogue scenes – to another level.

For example, montages work great in movies. Montages don’t work very well in scripts. That’s because movies are great for images and music. But you can’t see images and can’t hear music when you’re reading a script. In a screenplay, a montage is just a bunch of factual description a reader has to read through. Where’s the fun in that?

On the flip side, limited characters and limited locations work great in scripts because everybody who reads a screenplay wants it to read fast. So they love it when there’s any setup with 2-3 characters, minimal description, and a lot of dialogue. So if you have two characters trapped on a tower talking most of the time (“Fall”), a reader can get through that script in 30 minutes. It’s a dream read.

However, limited location movies, especially if they’re set somewhere stagnant, like a basement (the Duffer Brothers’ “Hidden”) become very boring on screen. That screenplay that read faster than lightning is boring to watch because it’s aesthetically boring to look at. Same background and little-to-no movement aren’t exactly cinematic.

This opens up a “4-D Chess” strategy to screenwriting because you’re now making choices about whether to write something that’s going to work in the script even if you know it’s not going to work in the movie (good idea for spec writers), or something that’s going to work in the movie even though it doesn’t work in the script (good idea for a writer who’s already hired). In other words, do you write for the ‘great read’ or do you write for the ‘great movie?’

It’s an interesting topic that I was thinking about the other day because I watched this show where, in a scene, two girl friends (I forgot their names but we’ll call them Sara and Nancy) needed to have a discussion about whether Nancy was going to marry her fiancé.

Whenever you have two people trying to work out a problem via dialogue, there’s a lot of variety in where you can set the scene. Theoretically, you can place a conversation anywhere. So, in this case, the writer placed it at a gym. Sara and Nancy were doing a workout routine with one of those giant tires that you flip over again and again. And, while doing so, they talked about whether the fiancé was marriage material.

The scene was actually okay, mostly because you were invested in the characters. But also because the movement and pauses and catching of their breath gave the conversation a little extra oomph.

However, I noted that, if you had read this scene in a script, nothing about this workout would affect how you read the scene at all. You could’ve set the very same scene at a cafe and it would’ve read the exact same. Because dialogue reads the same on the page whether your characters are working out or hanging out.

I’ll see this a lot, also, with characters doing the dishes together. Instead of placing your characters on a couch to have a conversation, you give them something to do, like dishes, while they have their conversation. Again, in a movie, that’s a good idea. But in a screenplay, it doesn’t matter where that conversation is had because we’re just reading the dialogue. We don’t care if Husband Joe properly places the egg-beater in the right dishwashing compartment.

The more I thought about this, the more I realized that the real problem here was that you wrote a scene that was so stale, you needed all this artificial movement — whether it be a giant tire workout or loading the dishwasher – to make up for the weak scenario. A scenario should never be so boring that it needs an extra on-screen boost.

Instead, you should be looking to write scenes that work on the page AND on the screen. To achieve this, you need a two-pronged approach.

First, you want the CONTENT of the scene to be good enough on its own that it wouldn’t matter where you placed it. You could have something as static as two characters sitting in bed together before they go to sleep. If the content of the conversation is compelling, we don’t care where it takes place, either on the page or on screen.

There’s no better example of this than Marlon Brando’s famous “I coulda been a contender” scene in On The Waterfront. It was the culmination of his entire life, this “contender” admission. So it was a very important moment. And, originally, the director, Elia Kazan, had this elaborate background projection sequence planned that would play behind the two characters as they had this conversation in the car.

But the projection broke, forcing them to film the scene with the back window closed, making it the most boring background ever. But it didn’t matter because the content of the scene was so strong. So make sure the content of the conversation is awesome first and foremost. That will take care of 75% of bad dialogue scenes.

Second, if possible, you want to use the physical scenario the characters are in TO ENHANCE the conversation, not just be incidental movement. Let’s say our married dishes couple is just getting things back on track after some infidelity by the husband. It still stings for the wife. So there’s pain there.

If these two had a dinner party with another couple and the wife thought the husband was too flirtatious with the guest wife, then that dishes scene is going to be a little more interesting. Just the way that the wife is handling the dishes. You could have her GRAB them and SHOVE them into the dishwasher to add an exclamation point to her frustration.

But guess what? You could make this scene EVEN BETTER if you used the scenario to enhance the conversation, not just use it as a minor visual distraction.

One thing you could do, for example, is to set the scene at a restaurant. The husband is taking the wife out to patch things up. But then, they get a really attractive waitress. And the waitress keeps coming in. She seems to be giving the husband more attention than the wife. This starts upsetting the wife. And now we’ve got a scene where, if you’ve taken care of the content part, we’re using the scenario they’re in to poke the bear – to fire up the coals beneath the dialogue. It becomes a much more interesting scene cause there’s an extra element going on.

I just watched this Portuguese show called “Gloria,” about the Cold War. Our hero, a spy who was transporting highly classified audio tapes across countries, regularly has to drive through checkpoints. But he knows all the checkpoint people so he’s able to shoot the sh— with them and move on.

In one of the scenes in the pilot, though, he’s chatting with a checkpoint friend but then, behind them, a new checkpoint guy strolls up. And this new guy decides to inspect the trunk, where our hero has hidden one of his audio tapes. So you’ve got your dialogue between the hero and his checkpoint friend. And then you’ve got the other thing going on behind them that, if it goes badly, our hero could be thrown in prison.

That scene’s going to work on the page and on the screen. Which is what I’m asking for here. First and foremost, make sure the scene works on the page. Cause you have no control over whether your script is going to get produced. All you have control of, at the moment, is making the read as good as possible.

Once you’ve got that down, see if you can improve the scene so that it also works on screen. Maybe it already does cause you got lucky. But if it doesn’t, see if you can find a way to create a scenario that enhances the good dialogue you already have. If you do that, you’re going to turn that good dialogue into great dialogue.

Guardians of the Galaxy 3 is, probably, the best movie Marvel could’ve released right now, the reason being that IT’S ITS OWN THING. The problem Marvel’s been facing lately is that all of its movies have been intertwined with one another, and while that was great when the MCU was cooking, it’s become the world’s draggiest anchor ever since it entered its Marvels/She-Hulk/Dr.Strange era.

Still, I couldn’t muster the enthusiasm to get myself to go watch the end of Starlord’s trilogy. There were two main reasons why. One, the film looks sad! It looks like it’s going to lean heavily into its feels and that’s not why I go to see big Hollywood films. It’s why I watch smaller films and some TV shows. But when I go to see a big movie, I want to have fun. I want my spirits to be lifted, not dragged down to Sadsville.

And to be honest, I don’t think Guardians has earned the right to have a big emotional ending. This isn’t Iron Man after 20 films. This isn’t Luke Skywalker at the end of the greatest trilogy ever. It’s Chris Pratt, people in weird makeup, and CGI creatures acting goofy in space. Let’s be real here. People aren’t asking for Manchester by the Sea when they’re watching gun-wielding raccoons.

Then, of course, there was that second movie. That second movie was awwwwwful. It was weird. It was bumpy. It ditched its main character in favor of focusing on its two villains. Had that movie been good, I probably would’ve seen Volume 3 regardless. But the stink from that misfire still lingers in the back of my nostrils.

I’m so hot and cold when it comes to James Gunn. Never connected with his pre-Guardians content. Love Guardians Volume 1. Hated Suicide Squad. Loved the Peacemaker show. Hated Guardians Volume 2. I’m actually excited to see what he does with DC because he has an opportunity to dethrone the flailing Marvel. But this one? This Guardians 3 movie? I’m sitting this one out.

So, after my No Guardians For Me temper tantrum I just made you endure, did I give up on the weekend? Absolutely not. I did watch something. And that something ended up totally surprising me. It surprised me so much that I did research on the creator, Graham Yost, only to find out he was the writer of SPEED, one of the best action movies ever!

The show I watched was called Silo, which is a post-apocalyptic story about people who live in a giant underground silo city. Every once in a while, someone demands to go outside, convinced that the air isn’t poison and that humans can, once again, live on the surface. But all of these people make it a total of about 20 steps before they fall to the ground and die.

The pilot episode is about the silo Sheriff’s wife, who suspects that the governing body of the silo is lying to them, and that the outside is, indeed, livable. (**spoiler**) So she goes outside. And dies just like everyone else. The sheriff is left heartbroken. But as time goes on, he considers giving the outside a shot as well.

I actually read the book the show was based on (called “Wool,” which refers to the wool everyone has over their eyes) which started as a short story that the author, Hugh Howey, shared with an online group. The enthusiasm inspired Howey to turn the story into a novel (the first chapter in Wool, which was the original short story, is utterly riveting so I’m not surprised people fell hard for it). It’s very much like the “Lost” narrative where there are a lot of secrets and reveals, which makes it ideal for a TV show.

So then why isn’t anyone talking about it? They probably will as word gets out. But I think it has more to do with the fact that Apple has zero concept for how to promote a TV show. None of these streamers do, really, beginning with Netflix. But the thing about Netflix was it was a destination site. You went there looking to watch something then you saw the latest greatest Netflix show being promoted so you checked it out.

Apple TV not only doesn’t have enough material to be a destination site, it’s buried under too many layers of menus and buttons. Every time I fire it up, I feel like I’m turning on a nuclear reactor. Is this where the original shows page is? Or is it over here? I suppose Apple gets some credit for making me feel like a genius every time I find the show I came for. But the poor ease-of-use severely hurts its chances of anyone watching a show on its service.

Then, of course, it doesn’t spend on advertising. Which is bizarre for a company with a 1 trillion dollar market cap. Great shows are going to find an audience no matter whether they advertise or not. But everything else needs to build awareness. Apple literally has a media strategy whereby they don’t tell you about a new show and make it hard to find any show you do hear about. With that strategy, the ONLY way anybody’s going to be able to find your show is if it’s Game of Thrones level awesome. It baffles me that there are smart executives getting paid millions who don’t do anything about this.

Is Silo a great show? I don’t know yet. But the pilot is darn good.

I’m always surprised when something pulls me in. Since I know all the buttons and levers writers are pushing to get me to buy into their story, I’m hyper-aware that whatever I’m watching is being written. For that reason, it’s hard for me to get lost in a show/movie. But I got lost in Silo’s pilot.

What wizardry did the writer use to achieve this?

Well, they start by giving us an intense opening scene then flashing back. Yes, this is a cliche. But they do it well. They start us in the present, briefly setting up the world of the silo before the Sheriff tells the government he wants to go outside. The story makes it clear that this is a death wish, which is a nice way to intrigue the viewer.

That wasn’t what hooked me, though.

What hooked me was the story of the Sheriff and his wife once we flashed back. The entire episode takes place in the past and shows the Sheriff and his wife trying to conceive a baby.

I can’t emphasize this enough – when someone becomes hooked on your story, when they buy in – it’s almost always because of the characters. And it’s almost always because you’re being truthful with those characters. You’re showing us characters who are going through the same trials and tribulations that real people go through. It’s that authenticity that makes us care about them.

All the Sheriff and his wife care about is having a baby. That’s it. That’s all that matters to them. And each day that goes by, each day that they become a little less hopeful, pulls us closer to them, makes us feel more sympathy for them, makes us root a little harder that tomorrow will be the day they get pregnant. By the end of this pursuit, I was in love with these two. I was ready to run through a wall for them.

So when the wife says she wants to go outside, the equivalent of committing suicide, I was heartbroken. Cause I knew what that meant. I knew she wasn’t coming back and I knew that he would be wrecked.

It’s something I try to remind myself of all the time, whether I’m helping another writer or working on something myself. Don’t get distracted by the bells and whistles – the twists, the mysteries, the mythology, the double-crosses. If you make us care about your characters, we’ll follow you through any door. Hell, we’ll follow you right out the silo! Into that poisoned air.

Assuming we can find your show, of course.

Did we get duped?

All along, were the Russos, actually, bad filmmakers?

This is a bold, maybe even triggering, accusation.

But the question needs to be asked because I watched Citadel this weekend, the gigantically budgeted new Amazon show that uses the words “highly enriched uranium” in its very first scene — WHAT YEAR IS THIS? 1984??? — and it was created by the Russo brothers.

The show’s 51% Rotten Tomatoes score clearly isn’t accurate as the show can’t be measured in ripe and rotten tomatoes. It must be measured in those mass produced faded tomatoes you find at the big brand supermarkets, the ones so devoid of taste, you wonder if they can even legally be called tomatoes. If we’re measuring this show by those tomatoes, it gets 100%. Because it is 100% bland.

Since their Marvel experience, the Russos gave us their gritty miscast character piece, Cherry, which I hear did quite well at the cast and crew screening, the only people who actually saw the movie. They then gave us The Gray Man, possibly the most generic piece of action filmmaking the universe has been subjected to. And now this. This…. Whatever Citadel is. If nobody had told me, I might assume it was a very long commercial for a new fragrance.

The Russos have long been an anomaly. They were comedy directors, giving us the Owen Wilson film, “You, Me, and Dupree.” They then became TV show directors, helming episodes of Arrested Development, Happy Endings, and Community.

People thought Kevin Feige had lost his marbles when he gave the Russos a Marvel film (Captain America: Winter Soldier). But they delivered. That got them Captain America: Civil War and then the Avengers films, which turned them into household names.

But are the Russos merely beneficiaries of the Marvel formula at a time when it was at its most potent? Or are they actually exceptional?

Hollywood is a strange place that has the power to make people and things look bigger and better than they actually are. It’s a spin zone, the most formidable of all time. They can spin you up or, when they no longer need you, spit you out. It’s that spitting part that exposes you – that leaves you naked and bare. Those who were actually good survive this spitting. Those who don’t churn out an endless stream of tomato compost.

I watched this Jennifer Lawrence trailer for her latest movie, No Hard Feelings. The film, about an older woman who gets paid by a couple of parents to help their son lose his virginity before he goes to college, is the result of Lawrence “taking control of her career” and making her own choices, as opposed to doing her agents’ bidding. It literally looks like the worst film of all time.

I see that streak Lawrence was on with Hunger Games, Silver Linings Playbook, and American Hustle, and she just looked invincible. When you saw her getting nominated for Oscars, you didn’t bat an eye. It made sense because the Hollywood machine told you it made sense. This was one of the greatest actresses of our generation, they said, and we nodded like zombies who’d been promised fresh brains for dinner.

Since then, she’s made Red Sparrow, Serena, X-Men Apocalypse, Joy, Passengers, Mother, Dark Phoenix, Don’t Look Up, and Causeway – a stretch of extremely mediocre films. So which one is the real Jennifer Lawrence? Is it the one who went on that first streak or this one?

There’s an argument to be made that it’s so hard to make anything good in this town that if you can make even ONE great film, you’ve done the impossible. And if you can make three great films? You’ve done something 99.99999999% of people who come to Los Angeles never achieved. That cannot be a fluke. So why not celebrate that instead of focusing on all the duds they made?

Fair. But when you make five bad movies in a row (or six, or seven, or eight), it’s hard not to question whether you were as good as everyone said you were. Maybe the powers that be knew how to protect your weaknesses as an actor, or, in the Russos’ case, as directors.

If you’re looking to watch something actually good, I suggest staying away from Amazon’s solipsismistic snafu, and starting up Beef, on Netflix. I know some people have had a problem with this series because Amy Lau (Ali Wong) is the single most unlikable person on the planet. But if you push past the first couple of episodes, she becomes more tolerable.

The series is about a down-on-his-luck landscaper, Danny, who gets in a road rage incident with the CEO of a Goop-like wellness company, Amy. Danny chases her down, finds out her name, and starts stalking her. She retaliates in kind. And the two go back and forth at each other, the stakes escalating each time, until they’re at life-destroying levels.

There are a couple of great screenwriting lessons the series teaches us, the most obvious being the power of conflict. This entire series is built around a strong case of conflict. But conflict all on its own can’t carry a story. And it definitely can’t carry 10 episodes of television. You need something more.

So the second thing we’ve got is CLASS. These aren’t two rich people going at it. It’s not two poor people battling. It’s one rich person and one poor person. This turbo-charges the conflict because now we’ve got a class war. Also, in that initial interaction, Amy “wins” the road rage duel. Which creates an underdog scenario. Because, now, we want Danny to get her back. That’s why we’re going to tune in to the next episode. And the episode after that.

Then, like any good TV show, it starts giving you insight into these peoples’ lives, particularly Amy’s life, which, we find out, is a difficult one. She’s the breadwinner in her family. Her impotent husband is a lousy artist living off his much more famous father’s talent. So all the pressure is on her to make the money.

The screenwriters wisely create this storyline in which Amy is trying to sell her company to a bigger company, which places a ticking clock on the timeline and also places something at stake. If Danny were to do something that ruins this sale, Amy’s entire life would fall apart. Which means that all their interactions have weight. There are consequences involved.

The mistake a lot of amateur writers make is that there are never any real consequences to anything the characters do. You need to create situations where a conversation actually has implications on the characters’ lives.

The show still exhibits issues that Streaming TV hasn’t solved yet. Which is that if you’re a straight serialized show, your series inevitably falls into a rut. As a reminder, a serialized show has one continuous storyline, like Breaking Bad. A procedural show, like CSI, is a series of self-contained stories with little continuity or overarching plot.

It’s much harder to create episode ideas in a serialized show because, unlike Grey’s Anatomy, you can’t just throw in a new “sick person of the week.” You have to create brand new plot and, inevitably, these shows don’t have enough plot to fill up all that space. This forces them to start going backwards, via flashbacks, disrupting the forward momentum of the story. Which is exactly what happens in Beef, a show that is at its apex SPECIFICALLY when it has momentum.

The writers will always defend these choices as “getting to know the characters better,” and that’s true. We do learn more about the characters if we go into their pasts. But good writers are supposed to be able to do this WHILE KEEPING THE STORY MOVING. Any schmo off the street can write a flashback scene to some traumatic event that happened when their character was five. Real screenwriters are supposed to be able to come up with creative ways to get those details across within the flow of the story.

With that said, faults and all, I really liked this series. Beyond what I talked about, it does a great job expanding all of the characters’ lives. Characters who you think are going to be unimportant turn out to have these fully fleshed out complex storylines. I loved Danny’s lughead brother and Amy’s talentless stay-at-home husband. And the series isn’t afraid to get weird. It’s the polar opposite of Citadel. And gosh darnit, thank god for that.

One of the more controversial new screenwriters on the scene comes at us with yet another one of his high concept ideas

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: (from Black List) When her domineering director makes her film the same scene 148 times on the final night of an exhausting shoot, actress Annie Long must fight to keep her own sanity as she tries to decipher what is real, and what is part of his twisted game.

About: Screenwriter Collin Bannon routinely makes the Black List. He’s done it again here, as this script finished with 12 votes on last year’s list, the unofficial compilation of the “best screenplays in Hollywood.”

Writer: Collin Bannon

Details: 109 pages

Scarjo for Annie?

Scarjo for Annie?

All right, now that we’ve got all of that conflict out, let’s take things down a notch and review a screenplay about going crazy!

I remember reading these stories about Stanley Kubrick forcing Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman to do a million takes on Eyes Wide Shut and how Kidman, in particular, almost went insane.

Then later, probably because he was inspired by Kubrick, David Fincher did the same thing to his actors. I remember Edward Norton being particularly thrown by the first scene he shot for Fight Club. Norton thought he did a pretty good job on take one. But Fincher ended up making him do 20 more. And not just doing the takes, but not giving any direction. I got the feeling from Norton that it was a bit of a mind f—k.

I think the idea of tons of takes is to strip the acting away from the actors. And just have them “be.” I’m not convinced it works. I guess if a scene requires you to look emotionally spent it might work. But it’s hard to give when you’ve been told you’ve failed 27 times in a row.

So I thought building a movie around this concept was cool. It’s also a unique way into a loop narrative. Whenever you can exploit a trend in a way that doesn’t feel like the trend, I always give writers props for that.

It’s 1981 and we’re filming an elevated horror movie (Think The Exorcist, not Friday the 13th) in the middle of some eastern European country. At the start of the script, Annie, our hero, is at her wit’s end. They’ve filmed the entire incredibly intense movie. There’s only one scene left. And Annie is desperate to finish so she can get home for her cancer-stricken mother’s surgery.

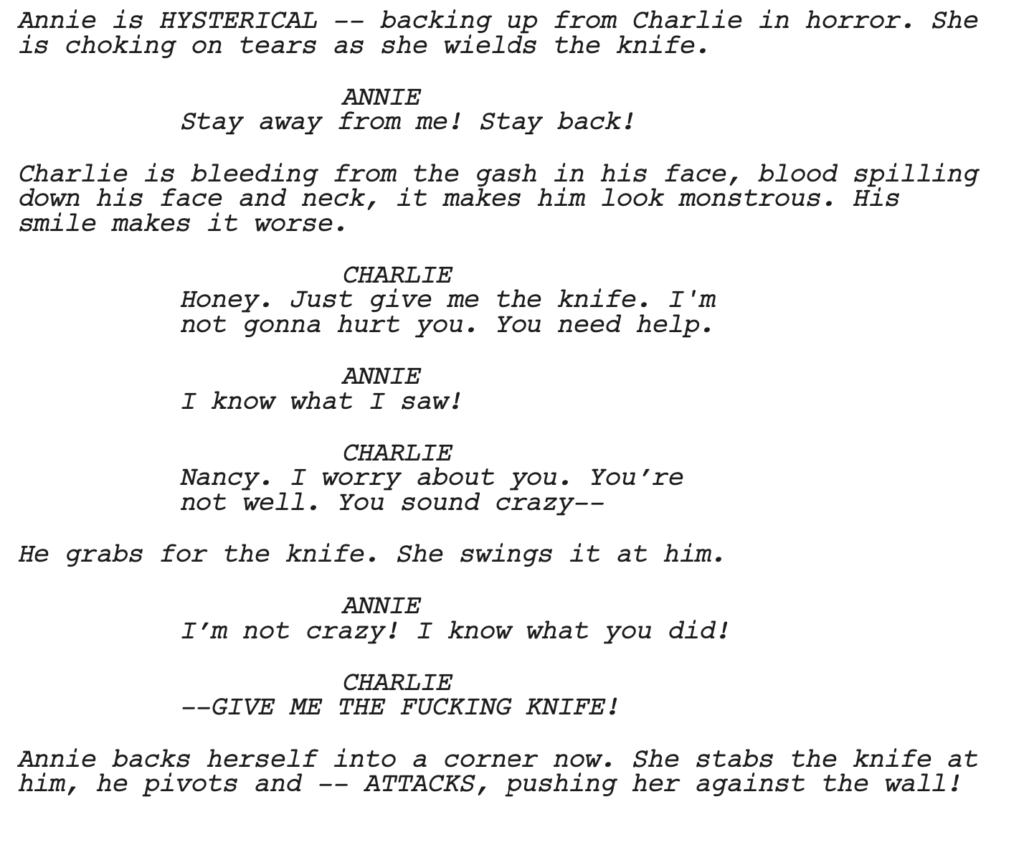

There’s one man in the way, though. Howard Bloch. I could get detailed about who Bloch is but just think: Stanley Kubrick. The final scene in question has Annie’s character fighting with her husband in their bedroom, who she seems to suspect did something terrible – maybe even murdered someone. Annie is screaming at him that she’s not crazy, she knows what he did, which leads to a physical altercation.

Every time they shoot the scene, Bloch says, “Let’s go again.” Annie asks what changes he wants but he never answers her. He just says, “Let’s go again.” That alone would drive a person crazy. But to make matters worse, everyone on set seems to hate Annie, who, by the way, is the only woman on the entire production (this is 1981 remember). So she feels super isolated outside of her assigned personal assistant, Laszlo, who’s a sweetheart.

As the night turns into day, and 1 take turns into 20, then 50, then 70, Annie really starts to lose it. She’s convinced the eye-patch that the DP wears has switched eyes. She thinks the wallpaper in the bedroom has changed color. The photo on the wall of her character and her co-star’s character turns into a photo of her and her mom. She repeatedly sees her mom in the back of the set. She thinks one of the stunt doubles wants to assault her.

Then the worst imaginable thing happens. The hospital calls and lets Annie know that her mom passed away unexpectedly. Bloch apologizes profusely. He tells Annie that he’ll get her on a flight home immediately. But now Annie is determined. She asks Bloch if he got the take. Bloch confesses he did not. “Then let’s go again,” she says. It’s clear that nobody’s leaving until they GET THIS TAKE RIGHT.

The byline of this post is, “yet another high concept idea.”

Since I know “high concept” can be confusing, I want to explain why this idea is high concept. The best way to do so is by showing you what the “low concept” version of this idea looks like.

The low concept version of this is the aftermath of an actress who’s had a long day after trying to film a scene that wasn’t working. We see her depressed and struggling and maybe her boyfriend has to build her back up again for the next day. Another version would be an actress trying to make it through a tough production in general. Every day is a challenge and she’s beaten down by the process.

In other words, straight-forward boring explorations of what it’s like to be an actress on a difficult shoot.

The second you make it 150 takes, the whole concept takes on an elevated feel. It feels bigger. It’s more intriguing. This is what makes the concept “high,” is the clever elevation of the common interpretation of an idea.

But what about the execution?

I’m, self-admittedly, not a fan of descent-into-madness screenplays for one simple reason. The screenwriter never gets the line right between keeping the script understandable and the story crazy. They always bring the craziness and messiness into the writing itself so we’re not sure what’s going on. These scripts have to be understandable even if what’s going on in the story isn’t supposed to be understood.

That’s a hard balance for even experienced writers to master.

While Bannon’s tackling of the problem isn’t perfect, he does a pretty good job. He definitely captures this character’s insanity but I still, usually, understood what was going on. I think the reason he was able to do this was because he kept the story simple.

Literally, we’re on the same set filming the same scene over and over again. So when there are crazy elements like, say, a mysterious woman that nobody else can see walking around in the background, we’re able to identify that as the lone variable that has changed and therefore an extension of Annie’s psychosis.

Plus, Bannon added some smart elements to his screenplay that exploited the idea. For example, at one point, Annie’s P.A. accidentally lets out that Howard has been telling everyone on set to be mean and isolating to Annie so he can get the performance he wants out of her.

There’s also mystery elements. The hospital calls to inform Annie that her mother passed away. But we’re immediately questioning, did that really happen or did Bloch make that up in order to get a better performance out of her? So now we have this carrot dangling in front of us, pushing us to keep walking, cause we want to know if her mom really is dead or not.

In other words, it isn’t just about doing the scene over and over again. There are other unresolved threads. Thank God for that because the movie would not have worked if that was the only thing propelling the narrative. Lots of newbie writers would make that mistake, by the way. They’d only focus on what’s in the logline – the bare-bones interpretation of the concept. But movies are too long for that. You need to keep feeding the beast – the beast being the reader – new meals every ten pages or so to keep them interested.

The irony about this script is that if it was ever tuned into a real movie, it would have the exact same effect on the real actress who took the part. She would be shooting 300-400 takes of the same scene. Cause she’s shooting multiple takes to get each of the takes right within the story itself. You’d have to be crazy to volunteer for that. But maybe that’s the point.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your most clever dialogue lines are going to stem from YOUR CONCEPT. Your concept is the primary generator of all that is unique within your script. So if you want to write clever lines, lean into the concept. For example, early on, the hair and makeup guy comes up to Annie before she’s about to shoot her scene and he says, referring to her exhausted face, “Are those dark circles mine or yours?” Annie responds, “I think they’re mine.” “You make my job easier every day.” So, why is this a clever line? Cause the obvious line is, “You look like s—t. We need to get you back in makeup pronto.” That line contains the exact same sentiment, but is on-the-nose and, therefore, boring. A compliment that’s actually an insult delivered in a way to make the heroine feel bad about herself – that’s good writing.

Former winner: Blood Moon Trail

Former winner: Blood Moon Trail

You’ve got one day left to send your loglines into April’s Logline Showdown. I want some stupendous loglines to choose from so don’t hesitate to submit. Here are the submission details…

******************************************************

What: Title, Genre, Logline

Rules: Your script must be written

When: Send submissions by April 20th, Thursday, by 10PM pacific time

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Winner: Gets a review on the site

******************************************************

Seeing as we have a big logline weekend ahead of us, let’s talk about the ten biggest logline mistakes and how we can avoid them. In order to provide everyone with some context for what constitutes a good logline, here are the three winning loglines from this year so far.

Blood Moon Trail

In 1867 Nebraska, a Pinkerton agent banished to a desolate post for an act of cowardice finds a chance at redemption when he decides to track down a brutal serial killer terrorizing the Western frontier.

Call of Judy

When a lonely kid gets lost in a next-gen VR gaming experience, the only person who can rescue him is his mom, who’s never played a videogame in her life.

Rosemary

A prolific serial killer struggles to suppress her desire to kill during a weekend-long engagement party hosted by her new fiance’s wealthy, obnoxious family.

Now that you understand what we’re aiming for, let’s discuss the TEN biggest logline mistakes.

NOT GIVING US THE MAIN CHARACTER RIGHT OFF THE BAT

The first thing a potential reader wants to know is, who’s leading me through this story? We are human beings so the first thing we connect with are other human beings. Therefore, unless there’s no other option, you should start off by introducing us to your main character. We see that in all three of the above winners, with a minor exception in Blood Moon Trail, which takes three words before we get to the main character. There are exceptions to this but, for the vast majority of loglines, you want to introduce your main character right away.

LITTLE-TO-NO SPECIFICITY

This is one I run into with Rom-Coms, Action-Thrillers, and Horror loglines, as these genres are the most susceptible to cliches. But it can happen with any genre. It boils down to the writer only using generic characters, adjectives, and locations, leaving the logline absent of anything that stands out. If you want to know what this looks like, here’s Blood Moon Trail’s logline, but rewritten without specificity: “Back in the Old West, a cowardly cop searches the frontier for an evil killer.” Notice the absence of all the specific words that made the logline pop: 1867, Nebraska, Pinkerton agent, brutal serial killer, Western frontier.

NO HOOK

This is more of a concept problem than a logline problem. To be clear, if you don’t have a good concept, it’s almost impossible to make your logline work. A hook just means a fresh and/or elevated component to your logline that feels bigger than the kinds of things that happen in everyday life. We don’t usually hear about cops chasing down serial killers in the Old West. That’s what makes Blood Moon Trail stand out. Call of Judy has a mom who’s never played video games have to save her son inside of a video game. To understand why that’s a hook, imagine the same idea but with a gamer friend trying to save our hero as opposed to the mom. All of a sudden it just becomes a flat boring idea. And then with Rosemary, we have a serial killer who’s trying *NOT* to kill. That’s a hook. A killer who’s doing the opposite of what’s expected of her.

IRRELEVANT DETAILS

The reason writers make this mistake is because they know their script so well that they’re unable to identify the things that might sound confusing inside a logline. Remember, some stuff needs the context of reading the whole script to understand. Whereas, if you included that stuff in the logline, it doesn’t organically fit with everything else you’ve told us. Here’s an example: “An aging ballet dancer with a keen interest in electronics is given the opportunity of a lifetime when she’s recruited by the prestigious Mariinsky Ballet Company.” What in the heck does having a keen interest in electronics have to do with this story?? Why would you include that in the logline? Maybe it *does* make sense in the context of the screenplay. But it doesn’t make sense in this abbreviated pitch of the story. Which is why you shouldn’t include it.

COMPETING ELEMENTS THAT DON’T ORGANICALLY CONNECT

I read a lot of loglines where the main elements don’t connect and, sometimes, even contrast with one another. Here’s an example: “A man with Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome, a rare condition wherein a person rapidly ages, learns that his father was a famous tomb raider and heads to Bolivia to seek out the treasure his dad died attempting to find.” What does the first half of the logline have to do with the second half? You’ve got two separate ideas here and you’re trying to cram them into the same movie. That RARELY works.

AN ENDING THAT SIMMERS OUT

This one always kills me. The writer will have this big catchy opening to his logline and pay zero attention to the logline’s climax, letting it die a slow quiet death. I’m talking about loglines like this: “A mountain climber who inadvertently disturbs a family of bloodthirsty sasquatches on Mount Kilimanjaro must rely on his smarts if he’s to escape the beasts and make it all the way down the mountain, a challenge that will test him both mentally and spiritually.” Notice how unevenly stacked this logline is. The first half is really exciting. The second half puts us to sleep. Always end the logline with a bang. All three of our winners did that.

THE OVERSTUFFED BURRITO LOGLINE

If you’ve ever been to Chipotle, you know what this one looks like. Those crazies try to cram everything into that burrito. Inexperienced writers do the same with their loglines. I understand their rationale. They want to make sure that all the relevant information is included so that reader knows absolutely EVERYTHING they’re going to get in the script. But that’s not how loglines work. Loglines only have space for the main character, the hook, and the central conflict. Generally speaking, try to stay under 30 words. 35 if you absolutely need those extra 5 words. Here’s what an overstuffed logline looks like: “A retired liberal political commentator must overcome her fear of the Bible Belt when she meets a conservative Alabama man online and moves in with him, but her fears are unfortunately realized when she must deal with his arrogant stepson, his weird paddle-ball obsessed neighbor, as well as overcome the church group who have declared her public enemy number 1 when she turns down their Sunday mass invitation.”

PROTAGONIST ADJECTIVE OVERLOAD

This is a small one but I see it a lot. It’s when writers go adjective crazy on their protagonist. They’ll include three, sometimes even four, adjectives to describe them. My advice when it comes to protagonist adjectives is to use one, two adjectives tops. And, keep in mind, a job title (accountant) or a label (serial killer) is an adjective. So instead of saying, “A young impressionable conflicted comedic actor,” you’d say, “A comedic actor.” I know it doesn’t tell the reader the whole story of who your protagonist is. But tough cookies. Loglines aren’t meant to tell the whole story. They’re the “poster” of your screenplay. They have to be succinct and to-the-point.

PLATITUDE FEVER

Here’s the definition for platitude: “A remark, statement, or phrase, that has been used too often to be interesting or thoughtful.” These are death for a logline yet writers use them all the time. And they make your logline both boring and empty. Funny enough, I asked ChatGPT to write me a platitude filled logline. This is what it came up with: “In a world where dreams are meant to be chased, and the only thing standing between success and failure is the courage to try, a plucky young underdog sets out on a journey of self-discovery and redemption.” “In a world.” “Where dreams are meant to be chased.” “The only thing standing between success and failure.” These are platitude phrases and mean nothing. Sometimes, you can use a single platitude to bridge relevant parts of your logline. But I would avoid them if you can. They somehow make everything sound like nothing.

CLUNKY PHRASING

“Clunky” boils down to using too many words and phrasing them incorrectly. It’s something that can be fixed by simplifying. Here’s the Rosemary logline, but written by a writer with clunky phrasing: “Trying to suppress her desire to kill, for which she is obsessive, a prolific and eccentric serial killer attempts to suppress her usual desire for bloodletting while experiencing a weekend-long engagement party that is being held for the richest of the rich.”

NOW GET THOSE LOGLINES IN BY 10PM PACIFIC TIME TONIGHT! (THURSDAY)

Need logline help? I’m here for you! Logline consults are just $25 for basic (analysis, rating, and logline rewrite) and $50 for deluxe (same as basic plus you get unlimited e-mails until we get the logline perfect). E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line: LOGLINE CONSULT.