Search Results for: F word

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Biopic

Premise (from writer): After the entire Kringle clan is murdered, Santa’s illegitimate son is forced to save his least favorite holiday from a menagerie of supernatural fuckwits.

Why You Should Read (from writer): My name’s Otis J. Kringle and I’m not a screenwriter — I’m fucking Santa Claus. Hang on, that came out wrong, as I am not actually “fucking” Santa — that would be weird and (as you’ll see) necrophilia. More like, I AM Santa Claus. I didn’t used to be, mind you. Truth be told, I’ve always considered Christmas to rank somewhere between getting a colonoscopy from Edward Scissorhands and watching FAILURE TO LAUNCH on a neverending loop. But alas, events unfolded that led me to pick up the jolly red mantle, events like stealing a UPS truck, getting thrown in jail, stepping in reindeer shit, throwing down in fisticuffs with Frigid Bitch and Jack Frost, riding flying lions, massive mall sing-a-longs, things of this nature. I know, right? I was pretty amazed, too. So amazed, I felt the need to share and find an outlet for my story (and movie, because who doesn’t love a new Christmas flick?), namely ScriptShadow. What can I say — I read your site, love the shit out of your site, and as far as I’m concerned, this makes it to a Friday review, everybody who reads your site will be put on the Nice List this year. Even Grendl. I know when you’re sleeping and when you’re awake, — Otis J. Kringle

Writer: Otis Kringle

Details: 97 pages

It’s rare that we get a screenwriter who writes a story based on his own life, which means we should consider today a treat. What makes this even specialer is that our writer appears to be related to Santa Claus. I’m still working on verifying this but I’m 2-4% sure that it’s true. And with the Christmas shopping season starting up next week, what better time to celebrate a Santa-inspired screenplay? Or a Santa-gets-slaughtered-inspired screenplay?

Now I must say that all this murder and mayhem hinted at in the logline has me worried. I’m a Christmas purist. I watch It’s A Wonderful Life every year on Christmas Eve. I download that Band-Aid song and listen to it on repeat. I even purchase egg nog despite the fact that I hate it, just so I can look at it in my fridge and feel festive. Is Otis Kringle about to ruin all that?

In a word, yes.

In another word: “fisting.” As in we’re told on page 1 to go fist ourselves.

Now I’m no doctor, nor do I play one on the internet. But I’m pretty sure that’s physically and biologically impossible. Gonna do a WebMD search on this later to make sure.

Our loser hero, Otis Kringle, the man responsible for telling us to fist ourselves, happens to be the illegitimate son of Santa Clause, who apparently slipped down Otis’s mother’s chimney many years ago, injecting her with many presents.

This will become important later after a dingbat elf in the North Pole named Dunbar Capp sings a song from a cursed book called the Santanomicon. He thinks he’s being jolly. But all he does is release Jolly Klaus, Santa Claus’s long lost half-uncle.

The axe-wielding Jolly slices up Santa along with the rest of his family, then demonizes Rudolph so that Rudolph can slaughter all of Santa’s reindeer.

Lucky for the planet, Dunbar and Blitzen get away and fly to America, where they approach Otis, the bastard child of Santa, to inform him that he’s the only one who can save Christmas. And the planet.

All he has to do is sing a song from the Santanomicon and Jolly will be sent back to the Badlands for another 1500 years. The problem is, all the songs are in another language, which poor Otis can’t read.

Complicating measures are Jack Frost and the Frigid Bitch, an oversexed couple who have likewise been stuck in purgatory for hundreds of years. Being freed allows them to have sex again and boy do they take advantage of it, even singing a song about all the sexual positions they’re going to enjoy together, which number at least a hundred.

Will Otis Kringle, who tells his story in first person, except when we’re around other characters, be able to save the day? Will you be able to save yourself after venturing into a story that introduces the world to the term “cunt brisket?” There’s no way to know for sure unless you read Otis Kringle Hates Christmas. And then fist yourself.

I hear that this Christmas, NBC will be debuting a live Peter Pan musical inspired by wholesome family values and the power of song. If, for whatever reason, this show gets cancelled, I’m sure “Otis Kringle Hates Christmas” can take its place. They’re practically the same movie. I mean, Peter Pan has a song about taking a literal exposition dump, doesn’t it?

Look, I think Otis has problems. He seems a tad angry. And that anger has manifested itself in a script more focused on shock value than story. Shock is a funny thing. It can work in small doses. One need look no further than South Park to see that. But it’s hard to make work if that’s the only thing you’re giving the audience for two hours.

South Park is actually a good gauge for how to make shock work. Underneath all its shocking humor, there’s an undeniable love South Park has for its characters. That love translates over to you loving the characters, and going along with whatever shenanigans, no matter how crass or dirty, the characters find themselves in.

I’m not sure Otis Kringle the writer has that same love for his characters (which is ironic, considering he is one of the characters), which prevents us from ever really connecting to Otis, Dunbar, and Blitzen. We get crass instead of heart. Swears instead of cares. And that creates a wall between reader and character that extends not just to the story, but to the comedy.

And this is why comedy’s the most subjective of all the genres. Everybody needs something different to laugh.

I need to care about the characters to laugh. I believe laughs come from stakes, come from us caring what’s on the line for the characters. And we can’t care about what’s on the line if we don’t connect to the characters in the first place. For example, in Neighbors, I really FELT the importance of our hero’s need to raise a family. So I cared that this frat next door was disrupting their world. And that’s what allowed me to laugh when they kept failing at their goal.

But I concede that not everybody feels this way. For a lot of people, a funny joke is a funny joke, regardless of whether you give a shit about the people involved in the joke. Otis Kringle graduated from the Kevin Smith school of comedy, where the jokes are based on nasty, on disgusting, on shocking and awing your reader. I’m not going to put that comedy down. All I can say is it’s not for me.

With that said, this script has a mission. And that’s to get your attention. And the easiest way to get people’s attention is to be loud and bold, and Otis Kringle is the loudest script I’ve read in years. Throw in some rule-bending (first person writing!), a bizarre mythology, and some snowflake-infused writing talent, and this script will find some fans.

It’s just that for me to become a fan, I have to see that love between writer and character. I need to feel at least some depth in our hero. Sometimes as writers we get so carried away with trying to do that one thing we set out to do when we conceived of the script, that we overlook other basic storytelling components required to make a script work. Otis may have had tunnel-vision in trying to make this that big attention-grabbing script, preventing him from remember that you still have to move people, you still have to make the audience feel something at the end.

The part of me that loves writers who take chances gives this a Millineum Falcon Lego Set present. But the script purist in me gives this a 25 dollar gift certificate to Best Buy. Hey, at least it’s not coal, right??

Script link: Otis Kringle Hates Christmas

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It’s really hard to keep a reader invested for 100 pages on shock alone. I’m sure it can be done, but that means continually one-upping yourself with something even MORE shocking every 10 pages. I wouldn’t want that assignment.

The value of screenwriting contests has been debated for years. I’ve gone on record as saying they’re an important tool in helping gauge where you are in your journey. If you’re not at least making the Quarterfinals (top 50 to top 100) of a screenplay contest, you might want to think about getting some personal feedback on your script to find out what you need to work on.

But don’t feel too bad if you’re not lighting up the contest circuit. Believe it or not, there are huge movies out there, movies that have made millions of dollars at the box office, that wouldn’t have even made it out of the FIRST ROUND of a screenwriting contest. Which just so happens to be the subject of today’s post.

That’s right, we’re going to look at ten movies, each of which were either critical or box office successes, that would’ve been laughed out of the big screenwriting contests. Some of these are obvious while others might surprise you. Commenting on these movies will be our hypothetical contest script reader, whose duty it is to explain why the script didn’t make the next round.

Now remember, you have to see these scripts as they’d be seen by the reader. These are naked scripts that have not become successful movies. They don’t have hot directors or actors attached to them. They’re scripts just like you would submit to a contest. With that in mind, let’s check out the list.

Transformers: Dark of The Moon – “Way too long with a story that’s painfully unfocused. Not a single character feels authentic or multi-dimensional. An over-reliance on crass humor, which becomes tired quickly. Way too much emphasis is placed on set-pieces, which would be okay if we understood why they were happening, but often we don’t. Pass.”

Annabelle – “Any horror script that contains a scene where a record player starts playing old timey music on its own is a surefire bet that there will be little if any originality on display. You may as well have a cat jump out of a cabinet while your character’s gone upstairs to ‘check out a noise.’ Horror’s number one enemy is cliché and when a writer shows not even a casual interest in avoiding the C-word, you know you’re in for a long predictable ride. Also, there isn’t a single memorable scare in the script. Death for a horror screenplay. Pass.”

The Monuments Men – “A strange unfocused tale that doesn’t always seem to know what it wants to be. Is it a drama? Is it a comedy? The idea is an interesting one, a story we’ve never heard before about World War 2. But the execution is all over the place. Why, for instance, did the writer choose to split our group of men up for the majority of the story? The group dynamic was the strongest part of the screenplay. To not recognize and take advantage of that shows a writer still learning the craft. It’s too bad. This could’ve been good. Pass.”

Interstellar – “Has the reckless feel of a first or second draft that the writer decided never to perfect. The dialogue is way too expository and on-the-nose, two signs of a beginning screenwriter. For example, lines like, ‘The MRI machines we no longer have could’ve spotted my wife’s cancer before she died.’ Yikes. While there are some interesting ideas about space exploration and time tacked into this overlong second act, everything comes crumbling down in the finale, when the writer tries to wrap up several corners he wrote himself into with trippy pseudo-science explanations. Time-travel is one of the hardest plots to get right, and this writer shows no dedication to figuring it out. Could show some promise with work. As it stands, pass.”

John Wick – “This is one of the most laughable set-ups for an action film I’ve ever come across. The main character, a retired hit man, goes after the Russian mafia because they killed his dog. Outside of a few fresh ideas in the second act, which include a hotel that deals exclusively with hit men, John Wick is bogged down in cliché after cliché. For example, must every action script end in an industrial location? Pass.”

Elysium – “Yet another sci-fi screenplay where the writer fails to explore his world on anything other than a cursory level. There’s no sense of scope at all. People are broken down into over-simplified “haves” and “have-nots.” An orbiting city has a half-ass plan in place for renegade ships breaking through, despite it being a common occurrence. Our main villain, a sword-wielding futuristic samurai type seems to have been ripped from another more fantasy-driven film, exemplifying the lack of foresight put into the script. He’s also bad for the sake of being bad, one of the easiest ways to spot a rushed draft. Feels like we’re five or six drafts away from this achieving its mark. Pass.”

The Counselor – “Script seems to put no value on clarity or narrative focus, often leaving the reader wondering where they are in the story, why things are happening, and what the characters plan to do next. I can’t tell if this was a deliberate choice, with the writer aiming for a high-brow audience who can read minds, or a first-time screenwriter who doesn’t yet understand how to make his plot points clear. Either way, the script completely falls apart when it reaches its apparent goal, the Counselor’s deal going bad, only to make us stick around for another 40 pages, where we’re forced to watch the main character wallow in pity. Writer must learn, amongst other things, that when you’ve reached your destination, the journey is over. Pass.”

Godzilla – “Who is the main character in this script? We’re led to believe it’s army man Ford Brody. But Brody doesn’t make a single decision throughout the entire screenplay. He instead follows a number of other people around and does whatever they tell him to do. Passive characters are the worst characters to lead a story, and Godzilla shows us why. Without a dominant character pushing us forward, we have no one to latch onto, and therefore no one to care about. Script also has a clunky opening, where we watch one parent’s death, only to go through twenty more pages of the other parent before their death. All of this before Brody is formally introduced. One wonders why not just start with Brody and look for ways to imply the backstory instead of show it. The script also spends so much time explaining where Godzilla is, what he’s doing, where he’s probably going next, and how to stop him, that there isn’t any time left for an actual story to develop. You’d think all the explaining would at least go towards setting up big memorable Godzilla set-pieces, but Godzilla only has a couple of featured scenes. A bizarre script that seems intent on avoiding everything that makes a story good. I can’t in good conscience send this one to the next round. Pass.”

Inside Llewyn Davis – “One of the stranger scripts I’ve ever read. The dialogue appears confident, even strong in places, yet there’s no story here to speak of, unless you count a man stumbling through the deliriously morbid world of folk music a story. The main character is such an asshole without a single redeeming quality, that watching him interact with others is akin to listening to metal scrape against concrete on concert-sized speakers. I’ve never read a script where the writer tried so adamently to make us hate their hero and I’m struggling to figure out what the point of that would be. Because we hate him so much, we don’t want him to succeed. Since succeeding is his goal, that leaves the audience with no choice but to root against his success. Can an entire movie hinge on this conceit? I’d say no way, Jose. Pass.”

The Master – “There’s a movie somewhere in this script, but the writer seems unwilling to find it. One of the script’s biggest problems is in its scene writing, as very few scenes have focus or structure. In fact, we’re often unsure where the scenes are headed or when they’re going to end. There’s a scene where the main character, Freddie, for example, gets fired from a department store, that could’ve ended on four different occasions. I like when writers give me something unexpected, but these scenes feel more like the writer himself didn’t know where he was going. The script picks up when religious leader Lancaster Dodd begins to mentor Freddie, only to delve back into an unfocused story that seems uninterested in having a point. Writer needs to get to the religious cult sooner, and focus more on the growth of the cult under the Lancaster and Freddie dynamic, as that’s when the script shines brightest. However, I have a hard time believing this writer is capable of writing a focused story. Pass.”

And there we have it! So what does this MEAN exactly? Does it mean screenplay contests are flawed? I don’t think so. I think it means Hollywood has a huge weakness in two areas. – the big budget flick and the writer-director vanity project. Both can end up bad for, ironically, completely opposing reasons.

The big-budget tentpole/franchise films have too many cooks in the kitchen. This results in either a highly compromised uber-safe film (Olympus Has Fallen) or the overly bloated film where every single idea gets added (The Amazing Spider Man 2).

The writer-director projects, when they go bad, go bad for the opposite reason. There’s only one cook in the kitchen. They don’t have to win over anybody with their script, so if the script is bad, there’s no checks and balances system to prevent them from making it.

If you’re a writer who wants to win a contest, you should be doing generally the same thing as a writer who’s trying to sell a script. Write something with some marketable element and then write the tightest and most entertaining story you can. If you do a good job at that, you’ll find yourself making it past the first round of contests easily, and possibly getting much further.

Genre: Comedy?

Premise: A racist southerner has a split personality that turns him into a devout liberal named Rodeo Rob, who believes he’s from the year 2525.

About: Vince Gilligan is the writer of what some consider to be the best television series ever, Breaking Bad. He originally wrote this script back in 1990, and over the years has honed it according to whomever became interested. The closest it got to production was in 2008, when Will Ferrell wanted to star in it. But a director was never found. Says Gilligan: “I don‘t know that the movie will ever get made because at the end of the day, it’s a little bit tricky, because it’s a comedy with the N-word in it.”

Writer: Vince Gilligan

Details: 129 pages! This is the 2008 draft that Will Ferrell was supposed to be in.

Chalk this one up to “What the fuuuuuuuuuhhhhh?”

I don’t know what I was expecting when I opened an early script from Breaking Bad’s Vince Gilligan, but I sure as hell didn’t know it would be this.

On the one hand, this is what you want from a writer – a script that actually takes some chances. But boy, I mean, at what point have you traversed so far off the reservation that the authorities have to come and get you?

Hmm, how to summarize this one. Okay, so there’s this guy named Earl. Earl is in his 40s, is nearly deaf (he wears a hearing aid), is extremely racist, and has a young daughter who’s also deaf. Earl spends his weekends playing a Confederate soldier in Civil War recreations.

Earl and his friends are off to one of these recreations when a black man cuts them off in traffic. This man’s name is Malcom, an academic who’s trying desperately to get into Harvard. At the next stoplight, Earl and his racist buddies, in their Confederate uniforms, get out and OVERTURN Malcom’s car with him in it.

Later, after the recreation, the curmudgeon-y Earl meets up with his ex-wife, Myra, and keeps complaining about this guy she’s been hanging out with, Rob. Later that evening, when the sun goes down, Earl takes his hearing aid off, and his whole demeanor changes. He’s now… Rodeo Rob!

Rodeo Rob, according to Rodeo Rob, is from the future, 2525 to be exact, where he lives on the moon. He’s time travelled back here to, I guess, help humanity. He’s also fallen in love with Myra, and Myra him. Of course, Myra must wake up every morning to Rodeo Rob becoming Earl again, a man she detests.

In the meantime, Malcom, our friend from the overturned car, becomes fascinated with Earl’s split-personality, and figures if he can study him and discover what’s causing the split, maybe it will get him into Harvard.

So Malcom moves next door to Earl (what??) and begins helping him. Of course, Earl wants nothing to do with this, so Malcom has to navigate around that tricky obstacle, mostly conversing with Rodeo Rob. But the ultimate goal is to bring Earl and Rodeo Rob back into one personality. It’s just a matter of which personality that will be.

When trying to separate your writing from everyone else’s writing, tone is one of the few ways you can do it. If you can mix the tone of, say, a comedy, with the stagey feel of the theater, you get Wes Anderson. If you can mix the tone of a documentary with the tone of a sci-fi pic, you get District 9. Put succinctly, mixing tones is a great way to stand out.

But there are some notes that just don’t sound right together. Trying to mix a goofy split-personality comedy, a la “Me, Myself, and Irene” with a serious look at racism? I’m just not sure how you make that work. And when tone is mixed incorrectly, it doesn’t matter what else you do. The script is never going to feel right.

If that analysis is too technical for you, I’ll put it layman’s terms: This script is f*cking weird.

Part of the problem is that Gilligan can never make a restrained choice. He always has to go to level 100 on the scale. For example, Earl’s alternate personality can’t just be the opposite of him (liberal and tolerant), he has to be the opposite of him BUT ALSO BELIEVE HE’S FROM THE YEAR 2525! When Malcom wants to study Earl and his disorder, he can’t do it from his office, he has to move next door to him???

The moment where I knew Gilligan had gone off his rocker, is when he shows us the backstory for what happened to Earl’s young daughter, who also has a hearing problem.

Now I assumed her hearing issue was a result of genetics. Oh no. We find out that a few years back, when Earl was drunk, he dressed up in a KKK sheet to go and scare a group of black people who were swimming in the pool. He brought with him a stick of dynamite to show how serious he was.

What he didn’t know, because he was wasted, was that his daughter was swimming in the pool as well. Well, Earl fell in the pool, the dynamite went off, and since sound travels more prominently through water (or so we’re told), both he and his daughter were turned deaf by the blast. That’s the backstory for them losing their hearing. I kid you not.

Further evidence that Gilligan was smoking the good stuff when he wrote this was a random dream sequence (which included a shark) from the point of view of the daughter. Because why not? The main storyline’s going along. You’ve shown the daughter three times up to this point. Why not hop into her head for a dream sequence? Another strange choice was Malcom being an organ transplant courier. In fact, on the day our Confederates flip his car, he’s carrying two corneas. What??

Three-quarters of the way through the screenplay, Earl’s extremely racist best friend, Booth, burns a cross in his front yard. I mean can we really write a comedy today with the KKK, the N-word, and burning crosses? I suppose the world was a different place back in 1990 when Gilligan first wrote this, but it wasn’t THAT different. I don’t see how someone could look at this and say it was a good idea.

I mean, I commend Gilligan for trying something different, but this feels like one of those early scripts a screenwriter never gives up on that they probably should. We’ve all got those. The nostalgia and bullheadedness keep us coming back to them. I loved Gilligan’s early-days pilot for that cop show he made for CBS. This? This is just… out there dude.

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a reason screenwriting software defines the non-dialogue section of text as “action.” It’s because that’s where you want to write ACTION. “Joe slams his fist down.” “Frank dashes over to his car.” “Carol spins to see the car coming at her.” Too many writers, however, think this section is called “description.” They like to use it for lines like, “Joe’s long hair never looks out of place. It’s like he keeps a personal stylist with him wherever he goes.” “Nearly everything in Frank’s apartment is green. It’s almost forest-like in its appearance.” “Carol crosses the city street, which is populated with early-morning commuters who haven’t had their lattes yet.” Obviously, you’re going to need to describe things in a script. And in small doses, the above examples are fine. It’s when that’s all you write where it becomes a problem. As a general rule, 80% of what you write in the action section should be ACTION, should be THINGS HAPPENING. — The reason Gilligan’s script was 130 pages was because it was deluged with unnecessary description. It made this one of the hardest scripts to get through all year. (note: There are exceptions to this action/description ratio, of course, but it’s almost always true)

Genre: Drama

Premise: An alcoholic who’s been told that his liver is about to give out must move in with the family he’s ignored his entire adult life.

About: “George” finished high up on the 2012 Black List. The writer, Jeff Shakoor, will get his first big-time TV writing credit when Netlfix premieres its show, “Bloodline,” about a rich family with some dark secrets. Shakoor wrote the second episode in the series. You can check out my review of that pilot here.

Writer: Jeff Shakoor

Details: 117 pages

Jon Favreau brought up a good point in that Hollywood Reporter Roundtable I linked to the other day. He said studios always want that likable main character driving the story. As you can imagine, the table bristled at the mention of the word “likable.” Ooh, that evil word. “Likable.”

Favreau pointed out that the very idea of a likable protagonist didn’t fit the hero journey template. In the hero’s journey, a character must have a flaw that they overcome over the course of the story. In most cases, that means starting in an “unlikable” place. The “likable” part only comes once the character transforms.

It’s an age-old problem. And while not every flaw must include an aspect of “likability” (your character’s flaw can be, for example, “not believing in one’s self,” a la Rocky), some of the more interesting flaws, such as selfishness, fall squarely in the path of the adjective.

What writers often forget, however, is the notion of balance. If you’re going to make your hero selfish, and therefore, “unlikable,” you need to establish an equity line of “likability” to balance it out. However, a lot of writers get so angry at the notion of Hollywood telling them they have to make their hero likable, they go in the opposite direction, making their character the embodiment of evil as a “fuck you” to the industry. That seems (to me at least) how we got our lead character in “George.”

60-something George’s alcoholism is so bad, that even when he’s told by his doctor that his liver will cease functioning and he’ll be dead in six months, George still wants a drink. It’s been this way for George’s entire adult life. All he cares about is his next beer, his next shot, his next bottle of Jack.

He figures he’ll spend his last days where he’s most comfortable. The bar. But there’s a problem with that. George is broke. He used to be able to get past that hiccup with his good looks and charm. But George is now in his 60s with that aging alcoholic’s face. Good looks and charm are no longer in his repetoire.

So George is forced to call his ex-wife, Myra, whom he, of course, asks for money. She tells him to fuck off. She’ll give him a place to stay until he dies. But the last thing she’s doing is giving him a stack of cash so he can end his life a couple months early.

Going back home means meeting his now-adult children for, really, the first time, since he was out drinking throughout their entire childhood. The idea is for George to foster some sort of late-life relationships with them, but George has never been the sentimental type. He’s not above asking his grandkids for money so he can secure his next drink.

Of course, George is pulled into his family members’ lives merely by being around (such as when he catches his teenage grandson partaking in a homosexual act) and while he’s far from helpful in these situations, he’ll offer guidance if it involves some level of amusement for himself. Will George finally change before he dies? Will he realize what truly matters in life? Only one way to find out.

I love the whole “unlikable” debate. I think it’s the most fascinating argument in screenwriting. Because Favreau is right. You have to start your hero in a negative place if you want to arc them to a positive place. Nobody arcs from positive to positive. And yet attempts to utilize unlikable characters almost always end in bad screenplays (you guys tend to see all the professional scripts where this works. I see the hundreds of amateur scripts where it doesn’t). It’s hard to root for anybody you hate.

I think there are two types of selfish. There’s fun selfish, a la Bill Murray’s character in “St. Vincent” (spraying water at the neighbors) And then there’s mean selfish, which can probably be equated to a character like Melvin Udall from “As Good As It Gets” (telling people their lives are miserable). Obviously, the “mean selfish” character is a lot harder to pull off. And I’m still not sure how they did it in “As Good As It Gets.”

But they tried it here, and I’m afraid it didn’t work. Shakoor doesn’t even try and build up any “likable equity” with George. George grabs the breasts of his nurses, telling them how hard he would’ve nailed them in his heyday, then goes to the bar, drinks 5 shots in a row, and laughs at the bartender when he tells him he can’t pay for them. It’s pretty brutal.

The first “nice” moment in “George” doesn’t come until page 50 or so, when he helps his grandson, Michael, go find a hooker to see if he’s gay or straight. That’s a long time to wait until the very first nice thing your character does.

I was re-watching Frozen the other day – one might say the “anti-George” – and I realized that if you establish a likability IMMEDIATELY with your characters, you can get away with a lot later on. We establish sisters Anna and Elsa lovingly playing with one another, then harshly broken apart, then pining for one another again, and it pretty much allows them to do whatever they want with Elsa , the Ice Queen” moving forward. We saw how sweet she was capable of being. We pine to see that sweetness again.

It would make sense then, that the opposite would hold true. If you make us dislike your character right away, that feeling is probably going to follow the character throughout the movie.

From a technical standpoint, “George” never quite resonated either. The script is jam-packed with dialogue, which is fine. But 90 percent of it is George insulting people. I’ve said this before. You need to add variety to your dialogue. We all have our patterns, the things we like to do with dialogue. But if you ONLY do that, you’ll tire the reader out. 50 insults in and we were only on page 20 – I needed more variety than that.

So why did this script end up on the Black List? Well, The Black List likes to celebrate scripts that take chances – particularly scripts with unabashedly dark characters (even better if they’re dying – another Black List favorite). Everything from St. Vincent to Cake to Bad Words to The Social Network. If you’ve got a meanie main character, this is where you’re hoping to showcase it.

So by no means am I telling you never to write an unlikable main character. There are plenty of anti-establishment Hollywood folks who will give you the thumbs up for giving them something different. Just keep in mind that it’s always a tough balancing act and if you don’t get it just right, people are going to dismiss it out of hand.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Pay very close attention to what you’re doing with your main character early. Every little thing they do is affecting how we see them. We don’t know this person yet, so their actions are very powerful. They don’t tip, we see them as cheap. They hold the door open for the person behind them, we see them as thoughtful. Your character’s actions are more powerful than you think. Use them wisely.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Psychological Thriller

Premise (from writer): A young widow discovers her husband’s accidental death is the latest in a series of murders-for-profit reaching back more than a decade.

Why You Should Read (from writer): This is based on my published novel. In its review, Mystery Scene magazine described the book as “a story Hitchcock would have approved of.” Exactly what I was striving for.

Writer: John Joseph Moran

Details: 118 pages

Christoph Waltz for Seifer? No-brainer.

Christoph Waltz for Seifer? No-brainer.

Scripts that start out fun always seem to have an advantage over ones that don’t. It takes more effort to get into those moody reads and even when you do, they never quite read as fast as the fun ones. I’m not saying you should never write a drama, of course. But in the competitive world of spec writing where every variable counts, picking up something that moves quickly sure makes things easier.

And that’s the experience I had with The Benefactor. Even at 117 pages, it never really slowed down. But why do I still have a case of the reluctants when thinking about it? Something about it feels… how do I put it? Light. There’s a level of sophistication missing, which left my suspension of disbelief in constant flux. The Benefactor destroyed the Amateur Offerings competition two Saturdays ago so I know a lot of you read it. Maybe, then, you can help me figure out why I felt this way.

When 35 year-old Claire Medina’s husband is hit and killed by a car, it’s bittersweet. On the one hand, he was her husband and father to her daughter. On the other, he was abusive and an altogether terrible person. As much as Claire hates to admit it, there’s a freeing feeling to her husband being out of her life. It’s almost too good to be true.

It turns out that’s exactly the case. A month later, Claire is approached by the sinister Nikolas Seifer, who informs her that he runs a unique business. He finds troubling individuals, individuals that spouses or family members wouldn’t mind dead, and he kills them in what looks to be an unfortunate “accident.” Afterwards, he approaches the spouse and asks for half of their fortune as payment for improving their lives.

Half Claire’s fortune is a lot of money. So Claire tries to find something on Seifer to use against him. But this guy is clever. He’s implicated Claire for the murder of her husband in several ways in case she doesn’t pay up.

Eventually, Claire realizes the best option is to give Seifer the cash and be done with it. So that’s what she does. But 18 months later (yes, you read that right – we have an 18 month time jump), Seifer appears again and tells Claire that to complete the loop, she has to kill someone for Seifer, his next mark.

Claire decides to turn the tables though, encouraging her mark, Fanning, to fake his death in order to take down Seifer. As her and Fanning wait for their plan to take shape, they fall for one another. But just as they believe they’ve cornered Seifer, he turns the tables back on them, and Claire finds herself fighting for her life, as she’s implicated for the murder of Fanning’s wife, a murder she didn’t commit.

This was a wild one. Lots of twists and turns here. The danger with a lot of twists and turns though, is that unless you’re extremely diligent, you’re bound to create some plot holes. There were a good half-a-dozen times here where I stopped and went, “Waaaait a minute. Couldn’t they just…?”

Like Seifer’s system. It’s a clever premise, don’t get me wrong. A hitman predicts that you want your spouse dead and therefore does it for you, only asking for the money afterwards so there’s no way for you to get caught. The catch is, he extorts you for the money.

But why only target “bad” people in this scheme? Since he’s extorting the people for money afterwards either way, can’t he technically do this to anyone, bad or good? What’s the advantage of only targeting bad people? I suppose it’s a little easier to deal with someone who kinda likes the fact that their asshole husband is dead. But nobody’s going to be thrilled when you demand half their fortune for the hit, whether they hated their hubby or not.

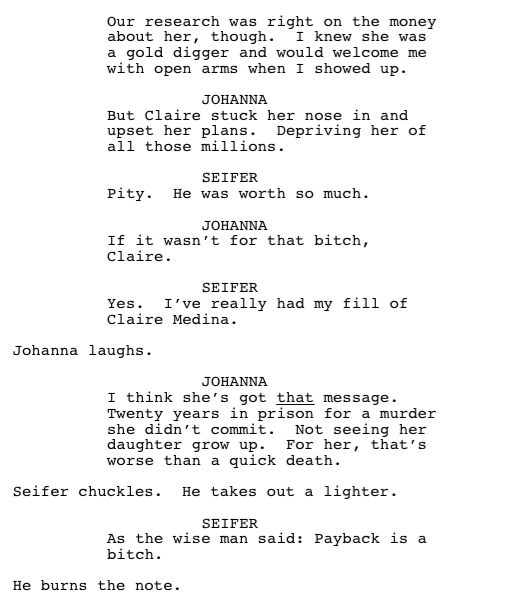

That’s what’s so frustrating about this script. It kept me reading all the way through. I wanted to find out what happened in the end. Yet it was littered with these lazy story pockets that weren’t believable for some reason or another. And again, it went back to a lack of sophistication. Let me show you a snippet of dialogue. Here, Seifer and his cohort, Johanna, are discussing how Fanning’s wife turned on Claire and their plan, allowing Seifer to gain the upper hand against them.

This is so over-the-top and on-the-nose, you can practically hear the sound of Seifer twirling his mustache, with Johanna “MUWHAHAHAING” in the background.

You may also notice the “explainy” nature of the dialogue (“Twenty years in prison for a murder she didn’t commit…”). There is a TON of this throughout the script. “Why can’t we go to the police?” “Because if Character A tells Character B we went to the police then it’ll mean we’re screwed. But if we follow Option C instead, then…”

Explainy dialogue almost always means the writer is using his characters to talk to the reader instead of his characters talking to each other. This is why this dialogue feels stilted and artificial, because it’s being directed at the wrong person. Dialogue must always, first and foremost, sound like two characters talking to each other. As soon as one of them stands up on their “explanation soapbox” to address the reader directly, you’ve pierced the reader’s suspension of disbelief.

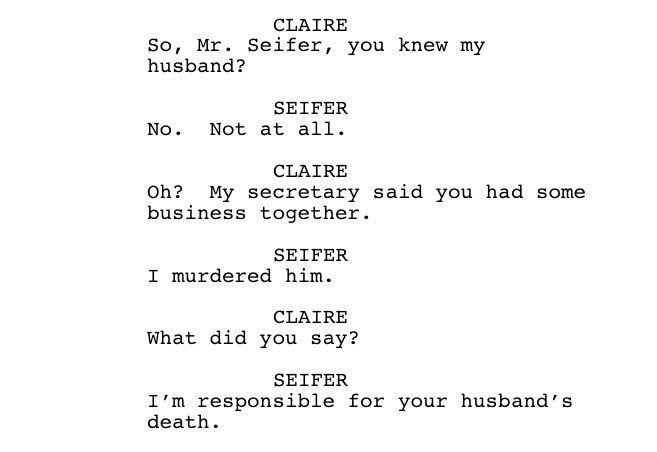

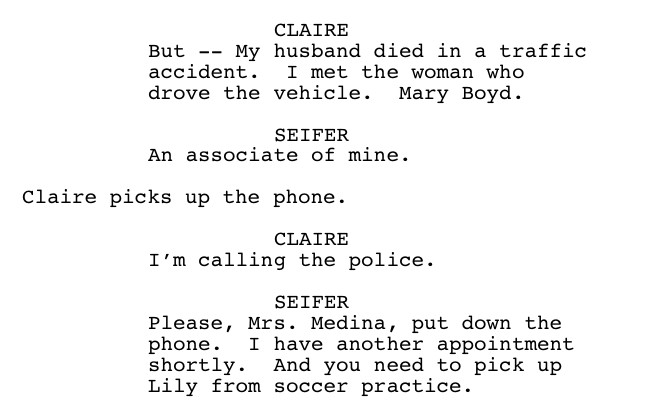

And that problem was persistent throughout much of the screenplay. Too much of the dialogue felt “off” for one reason or another. Take this exchange early in the script. Four weeks after her husband’s death, Claire is sitting in her office when Seifer arrives. Here’s the exchange.

While I don’t think this is terrible dialogue, it rang false (to me, at least). If someone says to you, “I murdered your husband,” are you really going to respond with, “But – My husband died in a traffic accident. I met the woman who drove the vehicle. Mary Boyd.” Someone just told you they are a murderer and you’re responding with a conversational rebuttal?

I could see freaking out. I could see realizing you’re in danger and enacting some sort of stall tactic while you figure out what to do. At the very least, note Claire freezing when she hears these chilling words. But without clarification, it reads like the ho-hum response of someone who’s just been accused of leaving the iron on. It’s emblematic of issues I had with the dialogue throughout.

The other big problem here has to do with time. Remember that unless you’re doing a period piece, you want the time frame for you movie to be as contained as possible. Any big time jumps mean a loss of momentum. But they also mean a lack of planning. It’s indicative of a writer who hasn’t worked hard enough to keep his story moving in one continuous timeline.

I mean the 18 month time jump is nothing short of a momentum assassination. If there’s any way to eliminate it, I’d do it. And then there’s Claire going to jail and the subsequent courtroom trial, which is another huge time jump. You have yourself a thriller here. You don’t want to end up in a boring courtroom drama sequence. Case in point. Imagine if Silence of the Lambs ended in a courtroom case. Do you think it’d still be considered a classic?

As soon As Claire goes to jail, get her out on bond, and have her and Fanning find and confront Seifert. It makes no sense to have your main character sitting in jail while this Fanning character, who we met less than 30 pages ago, searches for our villain.

Speaking of Fanning, I thought for sure he was going to turn out bad. I thought the whole idea behind Seifer’s system was that he targeted evil people. With Claire disrupting the system, I believed the irony would be that she’d pay the price. Fanning would end up doing something horrible to her. But even if you don’t explore that avenue, it seemed weird that all these people Seifer had killed previously were terrible human beings, yet Fanning turned out to be a great guy.

Anyway, I think Moran deserves some props for coming up with a unique premise and an unpredictable story that moves from start to finish. But to get this up to “worth the read” territory or higher, he needs to shore up some of the dialogue issues. I mean this is a “Hitchcock-like” story and I don’t remember a single conversation that included dramatic irony. Watch Psycho and note how nearly every dialogue scene contains dramatic irony (one character is lying to another). Fix that and the excessive time jumps and The Benefactor is going to be the real deal.

Script link: The Benefactor

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me (just missed a ‘worth the read’)

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware of characters being too “explainy” (“Why can’t we go to the police?” “Because a) it means blah blah, b) that would entail blah blah blah, and c) the villain would blah blah us”). Either cut all this explaining out or look for other ways to convey the message. For example: “Why can’t we go to the police?” Claire pulls out a newspaper with the headline, “Man Found Dead in Car.” “This is the last guy who tried to go to the police.”